- Open access

- Published: 08 October 2021

Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application

- Micah D. J. Peters 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Casey Marnie 1 ,

- Heather Colquhoun 4 , 5 ,

- Chantelle M. Garritty 6 ,

- Susanne Hempel 7 ,

- Tanya Horsley 8 ,

- Etienne V. Langlois 9 ,

- Erin Lillie 10 ,

- Kelly K. O’Brien 5 , 11 , 12 ,

- Ӧzge Tunçalp 13 ,

- Michael G. Wilson 14 , 15 , 16 ,

- Wasifa Zarin 17 &

- Andrea C. Tricco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4114-8971 17 , 18 , 19

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 263 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

160 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis with a growing suite of methodological guidance and resources to assist review authors with their planning, conduct and reporting. The latest guidance for scoping reviews includes the JBI methodology and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews. This paper provides readers with a brief update regarding ongoing work to enhance and improve the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews as well as information regarding the future steps in scoping review methods development. The purpose of this paper is to provide readers with a concise source of information regarding the difference between scoping reviews and other review types, the reasons for undertaking scoping reviews, and an update on methodological guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews.

Despite available guidance, some publications use the term ‘scoping review’ without clear consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardised use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the review’s objective(s) and question(s) are critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews.

Rigourous, high-quality scoping reviews should clearly follow up to date methodological guidance and reporting criteria. Stakeholder engagement is one area where further work could occur to enhance integration of consultation with the results of evidence syntheses and to support effective knowledge translation. Scoping review methodology is evolving as a policy and decision-making tool. Ensuring the integrity of scoping reviews by adherence to up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well-informed decision-making.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Given the readily increasing access to evidence and data, methods of identifying, charting and reporting on information must be driven by new, user-friendly approaches. Since 2005, when the first framework for scoping reviews was published, several more detailed approaches (both methodological guidance and a reporting guideline) have been developed. Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis which is very popular amongst end users [ 1 ]. Indeed, one scoping review of scoping reviews found that 53% (262/494) of scoping reviews had government authorities and policymakers as their target end-user audience [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews can provide end users with important insights into the characteristics of a body of evidence, the ways, concepts or terms have been used, and how a topic has been reported upon. Scoping reviews can provide overviews of either broad or specific research and policy fields, underpin research and policy agendas, highlight knowledge gaps and identify areas for subsequent evidence syntheses [ 3 ].

Despite or even potentially because of the range of different approaches to conducting and reporting scoping reviews that have emerged since Arksey and O’Malley’s first framework in 2005, it appears that lack of consistency in use of terminology, conduct and reporting persist [ 2 , 4 ]. There are many examples where manuscripts are titled ‘a scoping review’ without citing or appearing to follow any particular approach [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This is similar to how many reviews appear to misleadingly include ‘systematic’ in the title or purport to have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement without doing so. Despite the publication of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and other recent guidance [ 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], many scoping reviews continue to be conducted and published without apparent (i.e. cited) consideration of these tools or only cursory reference to Arksey and O’Malley’s original framework. We can only speculate at this stage why many authors appear to be either unaware of or unwilling to adopt more recent methodological guidance and reporting items in their work. It could be that some authors are more familiar and comfortable with the older, less prescriptive framework and see no reason to change. It could be that more recent methodologies such as JBI’s guidance and the PRISMA-ScR appear more complicated and onerous to comply with and so may possibly be unfit for purpose from the perspective of some authors. In their 2005 publication, Arksey and O’Malley themselves called for scoping review (then scoping study) methodology to continue to be advanced and built upon by subsequent authors, so it is interesting to note a persistent resistance or lack of awareness from some authors. Whatever the reason or reasons, we contend that transparency and reproducibility are key markers of high-quality reporting of scoping reviews and that reporting a review’s conduct and results clearly and consistently in line with a recognised methodology or checklist is more likely than not to enhance rigour and utility. Scoping reviews should not be used as a synonym for an exploratory search or general review of the literature. Instead, it is critical that potential authors recognise the purpose and methodology of scoping reviews. In this editorial, we discuss the definition of scoping reviews, introduce contemporary methodological guidance and address the circumstances where scoping reviews may be conducted. Finally, we briefly consider where ongoing advances in the methodology are occurring.

What is a scoping review and how is it different from other evidence syntheses?

A scoping review is a type of evidence synthesis that has the objective of identifying and mapping relevant evidence that meets pre-determined inclusion criteria regarding the topic, field, context, concept or issue under review. The review question guiding a scoping review is typically broader than that of a traditional systematic review. Scoping reviews may include multiple types of evidence (i.e. different research methodologies, primary research, reviews, non-empirical evidence). Because scoping reviews seek to develop a comprehensive overview of the evidence rather than a quantitative or qualitative synthesis of data, it is not usually necessary to undertake methodological appraisal/risk of bias assessment of the sources included in a scoping review. Scoping reviews systematically identify and chart relevant literature that meet predetermined inclusion criteria available on a given topic to address specified objective(s) and review question(s) in relation to key concepts, theories, data and evidence gaps. Scoping reviews are unlike ‘evidence maps’ which can be defined as the figural or graphical presentation of the results of a broad and systematic search to identify gaps in knowledge and/or future research needs often using a searchable database [ 15 ]. Evidence maps can be underpinned by a scoping review or be used to present the results of a scoping review. Scoping reviews are similar to but distinct from other well-known forms of evidence synthesis of which there are many [ 16 ]. Whilst this paper’s purpose is not to go into depth regarding the similarities and differences between scoping reviews and the diverse range of other evidence synthesis approaches, Munn and colleagues recently discussed the key differences between scoping reviews and other common review types [ 3 ]. Like integrative reviews and narrative literature reviews, scoping reviews can include both research (i.e. empirical) and non-research evidence (grey literature) such as policy documents and online media [ 17 , 18 ]. Scoping reviews also address broader questions beyond the effectiveness of a given intervention typical of ‘traditional’ (i.e. Cochrane) systematic reviews or peoples’ experience of a particular phenomenon of interest (i.e. JBI systematic review of qualitative evidence). Scoping reviews typically identify, present and describe relevant characteristics of included sources of evidence rather than seeking to combine statistical or qualitative data from different sources to develop synthesised results.

Similar to systematic reviews, the conduct of scoping reviews should be based on well-defined methodological guidance and reporting standards that include an a priori protocol, eligibility criteria and comprehensive search strategy [ 11 , 12 ]. Unlike systematic reviews, however, scoping reviews may be iterative and flexible and whilst any deviations from the protocol should be transparently reported, adjustments to the questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria and search may be made during the conduct of the review [ 4 , 14 ]. Unlike systematic reviews where implications or recommendations for practice are a key feature, scoping reviews are not designed to underpin clinical practice decisions; hence, assessment of methodological quality or risk of bias of included studies (which is critical when reporting effect size estimates) is not a mandatory step and often does not occur [ 10 , 12 ]. Rapid reviews are another popular review type, but as yet have no consistent, best practice methodology [ 19 ]. Rapid reviews can be understood to be streamlined forms of other review types (i.e. systematic, integrative and scoping reviews) [ 20 ].

Guidance to improve the quality of reporting of scoping reviews

Since the first 2005 framework for scoping reviews (then termed ‘scoping studies’) [ 13 ], the popularity of this approach has grown, with numbers doubling between 2014 and 2017 [ 2 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is the most up-to-date and advanced approach for reporting scoping reviews which is largely based on the popular PRISMA statement and checklist, the JBI methodological guidance and other approaches for undertaking scoping reviews [ 11 ]. Experts in evidence synthesis including authors of earlier guidance for scoping reviews developed the PRISMA-ScR checklist and explanation using a robust and comprehensive approach. Enhancing transparency and uniformity of reporting scoping reviews using the PRISMA-ScR can help to improve the quality and value of a scoping review to readers and end users [ 21 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is not a methodological guideline for review conduct, but rather a complementary checklist to support comprehensive reporting of methods and findings that can be used alongside other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. For this reason, authors who are more familiar with or prefer Arksey and O’Malley’s framework; Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s extension of that framework or JBI’s methodological guidance could each select their preferred methodological approach and report in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist.

Reasons for conducting a scoping review

Whilst systematic reviews sit at the top of the evidence hierarchy, the types of research questions they address are not suitable for every application [ 3 ]. Many indications more appropriately require a scoping review. For example, to explore the extent and nature of a body of literature, the development of evidence maps and summaries; to inform future research and reviews and to identify evidence gaps [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews are particularly useful where evidence is extensive and widely dispersed (i.e. many different types of evidence), or emerging and not yet amenable to questions of effectiveness [ 22 ]. Because scoping reviews are agnostic in terms of the types of evidence they can draw upon, they can be used to bring together and report upon heterogeneous literature—including both empirical and non-empirical evidence—across disciplines within and beyond health [ 23 , 24 , 25 ].

When deciding between whether to conduct a systematic review or a scoping review, authors should have a strong understanding of their differences and be able to clearly identify their review’s precise research objective(s) and/or question(s). Munn and colleagues noted that a systematic review is likely the most suitable approach if reviewers intend to address questions regarding the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness of a specified intervention [ 3 ]. There are also online resources for prospective authors [ 26 ]. A scoping review is probably best when research objectives or review questions involve exploring, identifying, mapping, reporting or discussing characteristics or concepts across a breadth of evidence sources.

Scoping reviews are increasingly used to respond to complex questions where comparing interventions may be neither relevant nor possible [ 27 ]. Often, cost, time, and resources are factors in decisions regarding review type. Whilst many scoping reviews can be quite large with numerous sources to screen and/or include, there is no expectation or possibility of statistical pooling, formal risk of bias rating, and quality of evidence assessment [ 28 , 29 ]. Topics where scoping reviews are necessary abound—for example, government organisations are often interested in the availability and applicability of tools to support health interventions, such as shared decision aids for pregnancy care [ 30 ]. Scoping reviews can also be applied to better understand complex issues related to the health workforce, such as how shift work impacts employee performance across diverse occupational sectors, which involves a diversity of evidence types as well as attention to knowledge gaps [ 31 ]. Another example is where more conceptual knowledge is required, for example, identifying and mapping existing tools [ 32 ]. Here, it is important to understand that scoping reviews are not the same as ‘realist reviews’ which can also be used to examine how interventions or programmes work. Realist reviews are typically designed to ellucide the theories that underpin a programme, examine evidence to reveal if and how those theories are relevant and explain how the given programme works (or not) [ 33 ].

Increased demand for scoping reviews to underpin high-quality knowledge translation across many disciplines within and beyond healthcare in turn fuels the need for consistency, clarity and rigour in reporting; hence, following recognised reporting guidelines is a streamlined and effective way of introducing these elements [ 34 ]. Standardisation and clarity of reporting (such as by using a published methodology and a reporting checklist—the PRISMA-ScR) can facilitate better understanding and uptake of the results of scoping reviews by end users who are able to more clearly understand the differences between systematic reviews, scoping reviews and literature reviews and how their findings can be applied to research, practice and policy.

Future directions in scoping reviews

The field of evidence synthesis is dynamic. Scoping review methodology continues to evolve to account for the changing needs and priorities of end users and the requirements of review authors for additional guidance regarding terminology, elements and steps of scoping reviews. Areas where ongoing research and development of scoping review guidance are occurring include inclusion of consultation with stakeholder groups such as end users and consumer representatives [ 35 ], clarity on when scoping reviews are the appropriate method over other synthesis approaches [ 3 ], approaches for mapping and presenting results in ways that clearly address the review’s research objective(s) and question(s) [ 29 ] and the assessment of the methodological quality of scoping reviews themselves [ 21 , 36 ]. The JBI Scoping Review Methodology group is currently working on this research agenda.

Consulting with end users, experts, or stakeholders has been a suggested but optional component of scoping reviews since 2005. Many of the subsequent approaches contained some reference to this useful activity. Stakeholder engagement is however often lost to the term ‘review’ in scoping reviews. Stakeholder engagement is important across all knowledge synthesis approaches to ensure relevance, contextualisation and uptake of research findings. In fact, it underlines the concept of integrated knowledge translation [ 37 , 38 ]. By including stakeholder consultation in the scoping review process, the utility and uptake of results may be enhanced making reviews more meaningful to end users. Stakeholder consultation can also support integrating knowledge translation efforts, facilitate identifying emerging priorities in the field not otherwise captured in the literature and may help build partnerships amongst stakeholder groups including consumers, researchers, funders and end users. Development in the field of evidence synthesis overall could be inspired by the incorporation of stakeholder consultation in scoping reviews and lead to better integration of consultation and engagement within projects utilising other synthesis methodologies. This highlights how further work could be conducted into establishing how and the extent to which scoping reviews have contributed to synthesising evidence and advancing scientific knowledge and understandings in a more general sense.

Currently, many methodological papers for scoping reviews are published in healthcare focussed journals and associated disciplines [ 6 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Another area where further work could also occur is to gain greater understanding on how scoping reviews and scoping review methodology is being used across disciplines beyond healthcare including how authors, reviewers and editors understand, recommend or utilise existing guidance for undertaking and reporting scoping reviews.

Whilst available guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping review has evolved over recent years, opportunities remain to further enhance and progress the methodology, uptake and application. Despite existing guidance, some publications using the term ‘scoping review’ continue to be conducted without apparent consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Because consistent and transparent reporting is widely recongised as important for supporting rigour, reproducibility and quality in research, we advocate for authors to use a stated scoping review methodology and to transparently report their conduct by using the PRISMA-ScR. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardising the use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the authors’ objective(s) and question(s) are also critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews. We contend that whilst the field of evidence synthesis and scoping reviews continues to evolve, use of the PRISMA-ScR is a valuable and practical tool for enhancing the quality of scoping reviews, particularly in combination with other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 44 ]. Scoping review methodology is developing as a policy and decision-making tool, and so ensuring the integrity of these reviews by adhering to the most up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well informed decision-making. As scoping review methodology continues to evolve alongside understandings regarding why authors do or do not use particular methodologies, we hope that future incarnations of scoping review methodology continues to provide useful, high-quality evidence to end users.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available upon request.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Article Google Scholar

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco A, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Paiva L, Dalmolin GL, Andolhe R, dos Santos W. Absenteeism of hospital health workers: scoping review. Av enferm. 2020;38(2):234–48.

Visonà MW, Plonsky L. Arabic as a heritage language: a scoping review. Int J Biling. 2019;24(4):599–615.

McKerricher L, Petrucka P. Maternal nutritional supplement delivery in developing countries: a scoping review. BMC Nutr. 2019;5(1):8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, De Micheli A, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:33–46.

Jowsey T, Foster G, Cooper-Ioelu P, Jacobs S. Blended learning via distance in pre-registration nursing education: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;44:102775.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: JBI; 2020.

Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):28.

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Inf Libr J. 2019;36(3):202–22.

Brady BR, De La Rosa JS, Nair US, Leischow SJ. Electronic cigarette policy recommendations: a scoping review. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):88–104.

Truman E, Elliott C. Identifying food marketing to teenagers: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):67.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. All in the family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):183.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Ghassemi M, et al. Same family, different species: methodological conduct and quality varies according to purpose for five types of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;96:133–42.

Barker M, Adelson P, Peters MDJ, Steen M. Probiotics and human lactational mastitis: a scoping review. Women Birth. 2020;33(6):e483–e491.

O’Donnell N, Kappen DL, Fitz-Walter Z, Deterding S, Nacke LE, Johnson D. How multidisciplinary is gamification research? Results from a scoping review. Extended abstracts publication of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play. Amsterdam: Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. p. 445–52.

O’Flaherty J, Phillips C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: a scoping review. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:85–95.

Di Pasquale V, Miranda S, Neumann WP. Ageing and human-system errors in manufacturing: a scoping review. Int J Prod Res. 2020;58(15):4716–40.

Knowledge Synthesis Team. What review is right for you? 2019. https://whatreviewisrightforyou.knowledgetranslation.net/

Lv M, Luo X, Estill J, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a scoping review. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(15):2000125.

Shemilt I, Simon A, Hollands GJ, et al. Pinpointing needles in giant haystacks: use of text mining to reduce impractical screening workload in extremely large scoping reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(1):31–49.

Khalil H, Bennett M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2020;18(1):95–100.

Kennedy K, Adelson P, Fleet J, et al. Shared decision aids in pregnancy care: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2020;81:102589.

Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:12–27.

Feo R, Conroy T, Wiechula R, Rasmussen P, Kitson A. Instruments measuring behavioural aspects of the nurse–patient relationship: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(11-12):1808–21.

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):33.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, et al. Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):31.

Cooper S, Cant R, Kelly M, et al. An evidence-based checklist for improving scoping review quality. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(3):230–240.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):208.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, Pham B, Straus SE, Langlois EV. Barriers, facilitators, strategies and outcomes to engaging policymakers, healthcare managers and policy analysts in knowledge synthesis: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013929.

Denton M, Borrego M. Funds of knowledge in STEM education: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;1(2):71–92.

Masta S, Secules S. When critical ethnography leaves the field and enters the engineering classroom: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;2(1):35–52.

Li Y, Marier-Bienvenue T, Perron-Brault A, Wang X, Pare G. Blockchain technology in business organizations: a scoping review. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii international conference on system sciences ; 2018. https://core.ac.uk/download/143481400.pdf

Houlihan M, Click A, Wiley C. Twenty years of business information literacy research: a scoping review. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2020;15(4):124–163.

Plug I, Stommel W, Lucassen P, Hartman T, Van Dulmen S, Das E. Do women and men use language differently in spoken face-to-face interaction? A scoping review. Rev Commun Res. 2021;9:43–79.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews - PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the other members of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) working group as well as Shazia Siddiqui, a research assistant in the Knowledge Synthesis Team in the Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto.

The authors declare that no specific funding was received for this work. Author ACT declares that she is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. KKO is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Episodic Disability and Rehabilitation with the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South Australia, UniSA Clinical and Health Sciences, Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre, Playford Building P4-27, City East Campus, North Terrace, Adelaide, 5000, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters & Casey Marnie

Adelaide Nursing School, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 101 Currie St, Adelaide, 5001, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters

The Centre for Evidence-based Practice South Australia (CEPSA): a Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 5006, Adelaide, South Australia

Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Terrence Donnelly Health Sciences Complex, 3359 Mississauga Rd, Toronto, Ontario, L5L 1C6, Canada

Heather Colquhoun

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute (RSI), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Heather Colquhoun & Kelly K. O’Brien

Knowledge Synthesis Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 1053 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1Y 4E9, Canada

Chantelle M. Garritty

Southern California Evidence Review Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, 90007, USA

Susanne Hempel

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 774 Echo Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5N8, Canada

Tanya Horsley

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Etienne V. Langlois

Sunnybrook Research Institute, 2075 Bayview Ave, Toronto, Ontario, M4N 3M5, Canada

Erin Lillie

Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Kelly K. O’Brien

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation (IHPME), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 155 College Street 4th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M6, Canada

UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Ӧzge Tunçalp

McMaster Health Forum, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Michael G. Wilson

Department of Health Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, 209 Victoria Street, East Building, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 1T8, Canada

Wasifa Zarin & Andrea C. Tricco

Epidemiology Division and Institute for Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College St, Room 500, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M7, Canada

Andrea C. Tricco

Queen’s Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, School of Nursing, Queen’s University, 99 University Ave, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 3N6, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MDJP, CM, HC, CMG, SH, TH, EVL, EL, KKO, OT, MGW, WZ and AT all made substantial contributions to the conception, design and drafting of the work. MDJP and CM prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrea C. Tricco .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Author ACT is an Associate Editor for the journal. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Peters, M.D.J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H. et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev 10 , 263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2021

Accepted : 27 September 2021

Published : 08 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scoping reviews

- Evidence synthesis

- Research methodology

- Reporting guidelines

- Methodological guidance

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley-Blackwell Online Open

A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency

a Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, N1G 2W1, Canada

b Division of Public Health Risk Sciences, Laboratory for Foodborne Zoonoses, Public Health Agency of Canada, 160 Research Lane, Suite 206, Guelph, Ontario, N1G 5B2, Canada

Andrijana Rajić

c Food Safety and Quality Unit, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153, Rome, Italy

Judy D Greig

Jan m sargeant.

d Centre for Public Health and Zoonoses, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, N1G 2W1, Canada

Andrew Papadopoulos

Scott a mcewen, associated data.

The scoping review has become an increasingly popular approach for synthesizing research evidence. It is a relatively new approach for which a universal study definition or definitive procedure has not been established. The purpose of this scoping review was to provide an overview of scoping reviews in the literature.

A scoping review was conducted using the Arksey and O'Malley framework. A search was conducted in four bibliographic databases and the gray literature to identify scoping review studies. Review selection and characterization were performed by two independent reviewers using pretested forms.

The search identified 344 scoping reviews published from 1999 to October 2012. The reviews varied in terms of purpose, methodology, and detail of reporting. Nearly three-quarter of reviews (74.1%) addressed a health topic. Study completion times varied from 2 weeks to 20 months, and 51% utilized a published methodological framework. Quality assessment of included studies was infrequently performed (22.38%).

Conclusions

Scoping reviews are a relatively new but increasingly common approach for mapping broad topics. Because of variability in their conduct, there is a need for their methodological standardization to ensure the utility and strength of evidence. © 2014 The Authors. Research Synthesis Methods published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

1. Background

The scoping review has become an increasingly popular approach for synthesizing research evidence (Davis et al. , 2009 ; Levac et al. , 2010 ; Daudt et al. , 2013 ). It aims to map the existing literature in a field of interest in terms of the volume, nature, and characteristics of the primary research (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ). A scoping review of a body of literature can be of particular use when the topic has not yet been extensively reviewed or is of a complex or heterogeneous nature (Mays et al. , 2001 ). They are commonly undertaken to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity in a topic area; determine the value and potential scope and cost of undertaking a full systematic review; summarize and disseminate research findings; and identify research gaps in the existing literature (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al. , 2010 ). As it provides a rigorous and transparent method for mapping areas of research, a scoping review can be used as a standalone project or as a preliminary step to a systematic review (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ).

Scoping reviews share a number of the same processes as systematic reviews as they both use rigorous and transparent methods to comprehensively identify and analyze all the relevant literature pertaining to a research question (DiCenso et al. , 2010 ). The key differences between the two review methods can be attributed to their differing purposes and aims. First, the purpose of a scoping review is to map the body of literature on a topic area (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ), whereas the purpose of a systematic review is to sum up the best available research on a specific question (Campbell Collaboration, 2013 ). Subsequently, a scoping review seeks to present an overview of a potentially large and diverse body of literature pertaining to a broad topic, whereas a systematic review attempts to collate empirical evidence from a relatively smaller number of studies pertaining to a focused research question (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Higgins and Green, 2011 ). Second, scoping reviews generally include a greater range of study designs and methodologies than systematic reviews addressing the effectiveness of interventions, which often focus on randomized controlled trials (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ). Third, scoping reviews aim to provide a descriptive overview of the reviewed material without critically appraising individual studies or synthesizing evidence from different studies (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Brien et al. , 2010 ). In contrast, systematic reviews aim to provide a synthesis of evidence from studies assessed for risk of bias (Higgins and Green, 2011 ).

Scoping reviews are a relatively new approach for which there is not yet a universal study definition or definitive procedure (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Anderson et al. , 2008 ; Davis et al. , 2009 ; Levac et al. , 2010 ; Daudt et al. , 2013 ). In 2005, Arksey and O'Malley published the first methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews with the aims of clarifying when and how one might be undertaken. They proposed an iterative six-stage process: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results, and (6) an optional consultation exercise (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ). Arksey and O'Malley intended for their framework to stimulate discussion about the value of scoping reviews and provide a starting point toward a methodological framework. Since its publication, a few researchers have proposed enhancements to the Arksey and O'Malley framework based on their own experiences with it (Brien et al. , 2010 ; Levac et al. , 2010 ; Daudt et al. , 2013 ) or a review of a selection of scoping reviews (Anderson et al. , 2008 ; Davis et al. , 2009 ).

In recent years, scoping reviews have become an increasingly adopted approach and have been published across a broad range of disciplines and fields of study (Anderson et al. , 2008 ). To date, little has been published of the extent, nature, and use of completed scoping reviews. One study that explored the nature of scoping reviews within the nursing literature found that the included reviews ( N = 24) varied widely in terms of intent, procedure, and methodological rigor (Davis et al. , 2009 ). Another study that examined 24 scoping reviews commissioned by a health research program found that the nature and type of the reports were wide ranging and reported that the value of scoping reviews is ‘increasingly limited by a lack of definition and clarity of purpose’ (Anderson et al. , 2008 ). Given that these studies examined only a small number of scoping reviews from select fields, it is not known to what extent scoping reviews have been undertaken in other fields of research and whether these findings are representative of all scoping reviews as a whole. A review of scoping reviews across the literature can provide a better understanding of how the approach has been used and some of the limitations and challenges encountered by scoping review authors. This information would provide a basis for the development and adoption of a universal definition and methodological framework.

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of existing scoping reviews in the literature. The four specific objectives of this scoping review were to (1) conduct a systematic search of the published and gray literature for scoping review papers, (2) map out the characteristics and range of methodologies used in the identified scoping reviews, (3) examine reported challenges and limitations of the scoping review approach, and (4) propose recommendations for advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency with which they are undertaken and reported.

This scoping review began with the establishment of a research team consisting of individuals with expertise in epidemiology and research synthesis (Levac et al. , 2010 ). The team advised on the broad research question to be addressed and the overall study protocol, including identification of search terms and selection of databases to search.

The methodology for this scoping review was based on the framework outlined by Arksey and O'Malley ( 2005 ) and ensuing recommendations made by Levac et al . ( 2010 ). The review included the following five key phases: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The optional ‘consultation exercise’ of the framework was not conducted. A detailed review protocol can be obtained from the primary author upon request.

2.1. Research question

This review was guided by the question, ‘What are the characteristics and range of methodologies used in scoping reviews in the literature?’ For the purposes of this study, a scoping review is defined as a type of research synthesis that aims to ‘map the literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts; gaps in the research; and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and research’ (Daudt et al. , 2013 ).

2.2. Data sources and search strategy

The initial search was implemented on June 17, 2011, in four electronic databases: MEDLINE/PubMed (biomedical sciences, 1946–present), SciVerse Scopus (multidisciplinary; 1823–present), CINAHL/EBSCO (nursing and allied health; 1981–present) and Current Contents Connect/ISI Web of Knowledge (multidisciplinary current awareness; 1998–present). The databases were selected to be comprehensive and to cover a broad range of disciplines. No limits on date, language, subject or type were placed on the database search. The search query consisted of terms considered by the authors to describe the scoping review and its methodology: scoping review, scoping study, scoping project, literature mapping, scoping exercise, scoping report, evidence mapping, systematic mapping, and rapid review. The search query was tailored to the specific requirements of each database (see Additional file 1).

Applying the same search string that was used for the search in SciVerse Scopus (Elsevier), a web search was conducted in SciVerse Hub (Elsevier) to identify gray literature. The a priori decision was made to screen only the first 100 hits (as sorted by relevance by Scopus Hub) after considering the time required to screen each hit and because it was believed that further screening was unlikely to yield many more relevant articles (Stevinson and Lawlor, 2004 ). The following websites were also searched manually: the Health Services Delivery Research Programme of the National Institute for Health Research ( http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/ ), the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation ( http://php.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/main.php ), NHS Evidence by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence ( http://evidence.nhs.uk/ ), the University of York Social Policy Research Unit ( http://php.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/main.php ), the United Kingdom's Department of Health ( http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/index.htm ), and Google ( http://www.google.com ).

The reference lists of 10 randomly selected relevant articles (Hazel, 2005 ; Vissandjee et al. , 2007 ; Gagliardi et al. , 2009 ; Meredith et al. , 2009 ; Bassi et al. , 2010 ; Ravenek et al. , 2010 ; Sawka et al. , 2010 ; Churchill et al. , 2011 ; Kushki et al. , 2011 ; Spilsbury et al. , 2011 ) and eight review articles on scoping reviews (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Anderson et al. , 2008 ; Davis et al. , 2009 ; Grant and Booth, 2009 ; Hetrick et al. , 2010 ; Levac et al. , 2010 ; Rumrill et al. , 2010 ; Armstrong et al. , 2011 ) were manually searched to identify any further scoping reviews not yet captured. A ‘snowball’ technique was also adopted in which citations within articles were searched if they appeared relevant to the review (Hepplestone et al. , 2011 ; Jaskiewicz and Tulenko, 2012 ).

A follow-up search of the four bibliographic databases and gray literature sources was conducted on October 1, 2012 to identify any additional scoping reviews published after the initial search [see Additional file 1]. A search of Google with no date restrictions was also conducted at this time; only the first 100 hits (as sorted by relevance by Google) were screened.

2.3. Citation management

All citations were imported into the web-based bibliographic manager RefWorks 2.0 (RefWorks-COS, Bethesda, MD), and duplicate citations were removed manually with further duplicates removed when found later in the process. Citations were then imported into the web-based systematic review software DistillerSR (Evidence Partners Incorporated, Ottawa, ON) for subsequent title and abstract relevance screening and data characterization of full articles.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

A two-stage screening process was used to assess the relevance of studies identified in the search. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they broadly described the use of a scoping review methodology to identify and characterize the existing literature or evidence base on a broad topic. Because of limited resources for translation, articles published in languages other than English, French, or Spanish were excluded. Papers that described the scoping review process without conducting one and reviews of scoping reviews were excluded from the analysis, but their reference list was reviewed to identify additional scoping reviews. When the same data were reported in more than one publication (e.g., in a journal article and electronic report), only the article reporting the most complete data set was used.

2.5. Title and abstract relevance screening

For the first level of screening, only the title and abstract of citations were reviewed to preclude waste of resources in procuring articles that did not meet the minimum inclusion criteria. A title and abstract relevance screening form was developed by the authors and reviewed by the research team (see Additional file 2). The form was pretested by three reviewers (M. P., J. G., I. Y.) using 20 citations to evaluate reviewer agreement. The overall kappa of the pretest was 0.948, where a kappa of greater than 0.8 is considered to represent a high level of agreement (Dohoo et al. , 2012 ). As there were no significant disagreements among reviewers and the reviewers had no revisions to recommend, no changes were made to the form. The title and abstract of each citation were independently screened by two reviewers. Reviewers were not masked to author or journal name. Titles for which an abstract was not available were included for subsequent review of the full article in the data characterization phase. Reviewers met throughout the screening process to resolve conflicts and discuss any uncertainties related to study selection (Levac et al. , 2010 ). The overall kappa was 0.90.

2.6. Data characterization

All citations deemed relevant after title and abstract screening were procured for subsequent review of the full-text article. For articles that could not be obtained through institutional holdings available to the authors, attempts were made to contact the source author or journal for assistance in procuring the article. A form was developed by the authors to confirm relevance and to extract study characteristics such as publication year, publication type, study sector, terminology, use of a published framework, quality assessment of individual studies, types of data sources included, number of reviewers, and reported challenges and limitations (see Additional file 3). This form was reviewed by the research team and pretested by all reviewers (M. P., A. R., J. G., I. Y., K. G.) before implementation, resulting in minor modifications to the form. The characteristics of each full-text article were extracted by two independent reviewers (M. P. and J. G./K. G.). Studies excluded at this phase if they were found to not meet the eligibility criteria. Upon independently reviewing a batch of 20 to 30 articles, the reviewers met to resolve any conflicts and to help ensure consistency between reviewers and with the research question and purpose (Levac et al. , 2010 ).

2.7. Data summary and synthesis

The data were compiled in a single spreadsheet and imported into Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) for validation and coding. Fields allowing string values were examined for implausible values. The data were then exported into STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analyses. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the data. Frequencies and percentages were utilized to describe nominal data.

3.1. Search and selection of scoping reviews

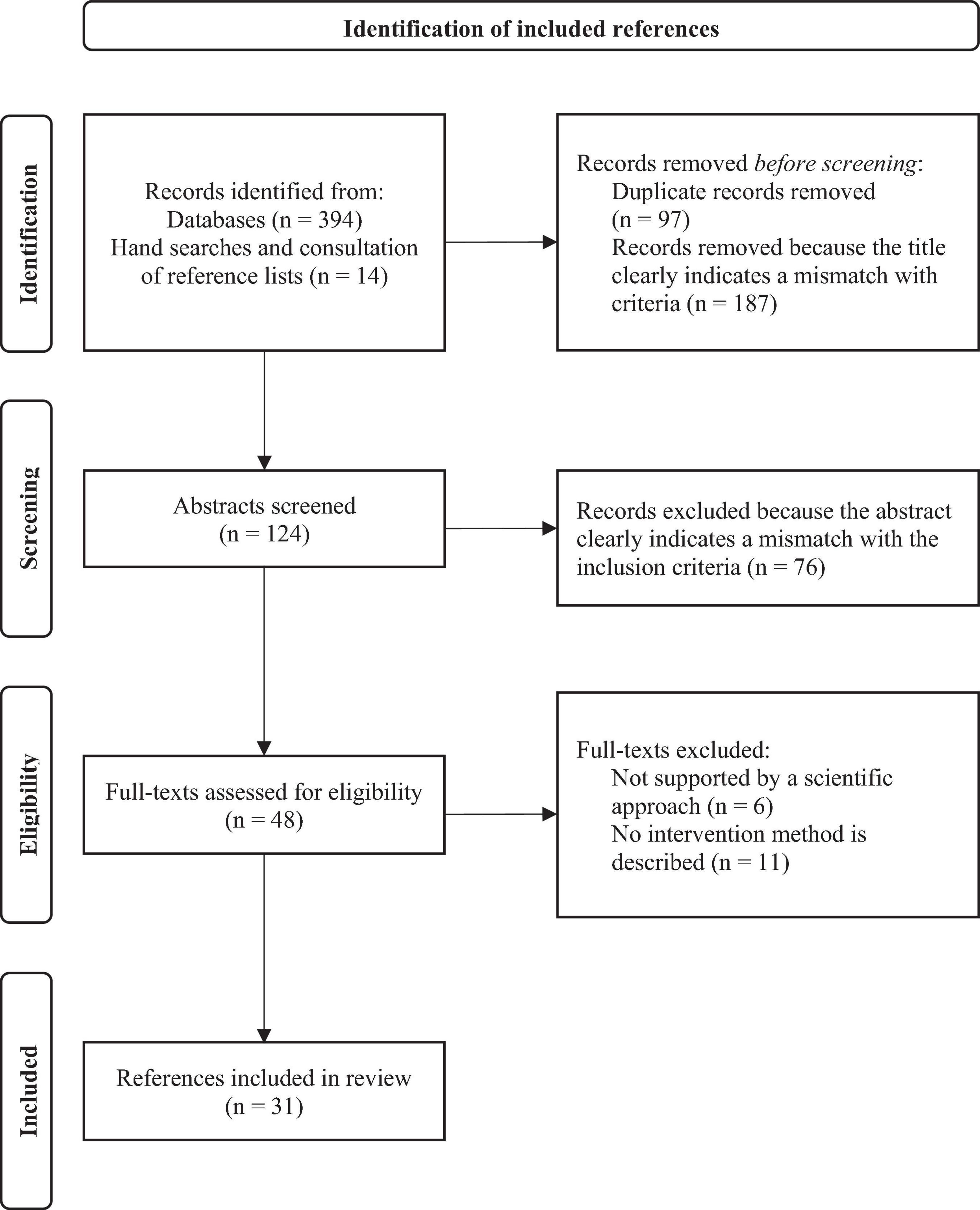

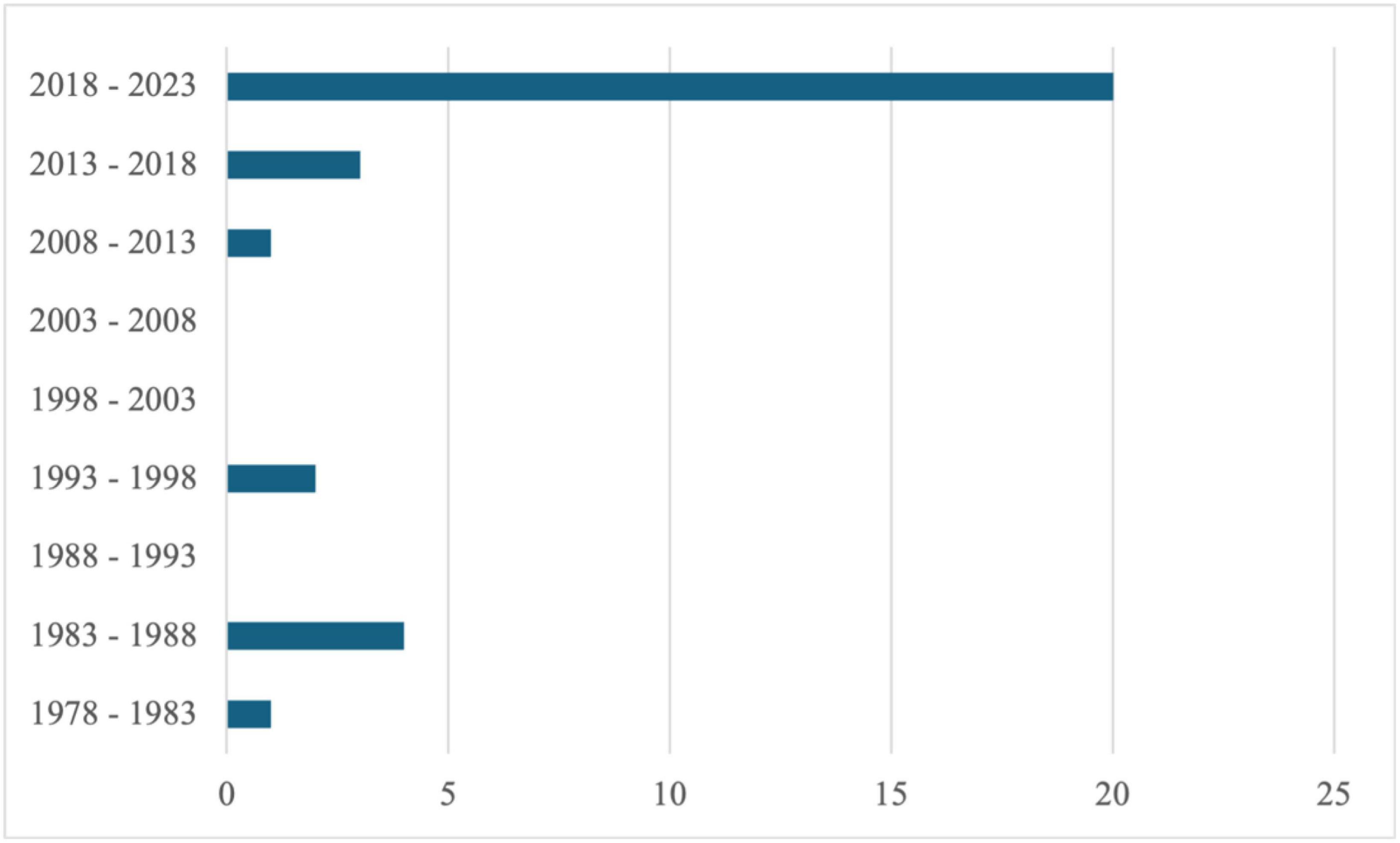

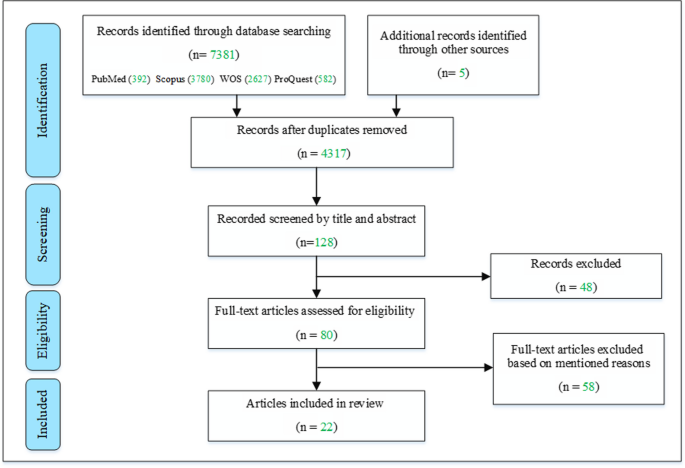

The original search conducted in June 2011 yielded 2528 potentially relevant citations. After deduplication and relevance screening, 238 citations met the eligibility criteria based on title and abstract and the corresponding full-text articles were procured for review. Four articles could not be procured and were thus not included in the review (Levy and Sanghvi, 1986 ; Bhavaraju, 1987 ; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2004 ; Connell et al. , 2006 ). After data characterization of the full-text articles, 182 scoping reviews remained and were included in the analysis. The updated search in October 2012 produced 758 potentially relevant citations and resulted in another 162 scoping reviews being included. In total, 344 scoping reviews were included in the study. The flow of articles through identification to final inclusion is represented in Figure Figure1 1 .

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process.

Many citations were excluded upon screening at the title and abstract level as several terms used in the search algorithm also corresponded to other study designs. For example, the term ‘scoping study’ was also used to describe studies that assessed the chemical composition of samples (e.g., Behrens et al. , 1998 ; Banks and Banks, 2001 ; Forrest et al. , 2011 ) and preliminary mining studies (Butcher, 2002 ; Bhargava et al. , 2008 ). ‘Scoping exercise’ also described studies that scoped an issue using questionnaires, focus groups, and/or interviews (e.g., Malloch and Burgess, 2007 ; Willis et al. , 2011 ; Norwood and Skinner, 2012 ). ‘Rapid review’ was also used to describe the partial rescreening of negative cervical smears as a method of internal quality assurance (e.g., Faraker and Boxer, 1996 ; Frist, 1997 ; Shield and Cox, 1998 ). ‘Systematic mapping’ was also used in studies pertaining to topographic mapping (e.g., Noda and Fujikado, 1987 ; Gunnell, 1997 ; Liu et al. , 2011 ) and mapping of biomolecular structures (e.g., Camargo et al. , 1976 ; Descarries et al. , 1982 ; Betz et al. , 2006 ).

3.2. General characteristics of included scoping reviews

The general characteristics of scoping reviews included in this study are reported in Table Table1. 1 . All included reviews were published between 1999 and October 2012, with 68.9% (237/344) published after 2009. Most reviews did not report the length of time taken to conduct the review; for the 12.8% (44/344) that did, the mean length was approximately 5.2 months with a range of 2 weeks to 20 months. Journal articles (64.8%; 223/344) and government or research station reports (27.6%; 95/344) comprised the majority of documents included in the review. The number of journal articles was slightly underrepresented as 10 were excluded as duplicates because the same scoping review was also reported in greater detail in a report. The included reports ranged greatly in length, from four pages (Healthcare Improvement Scotland, 2012 ) to over 300 pages (Wallace et al. , 2006 ).

General characteristics of included scoping reviews ( n = 344)

The included scoping reviews varied widely in terms of the terminology used to describe the methodology. ‘Scoping review’ was the term most often used, reported in 61.6% (212/344) of included studies. An explicit definition or description of what study authors meant by ‘scoping review’ was reported in 63.1% (217/344) of articles. Most definitions centered around scoping reviews as a type of literature that identifies and characterizes, or maps, the available research on a broad topic. However, there was some divergence in how study authors characterized the rigor of the scoping review methodology. The terms ‘systematic’, ‘rigorous’, ‘replicable’, and ‘transparent’ were frequently used to describe the methodology, and several authors described scoping reviews to be comparable in rigor to systematic reviews (Gagliardi et al. , 2009 ; Liu et al. , 2010 ; Ravenek et al. , 2010 ; Feehan et al. , 2011 ; Heller et al. , 2011 ). In contrast, some studies described the methodology as less rigorous or systematic than a systematic review (Cameron et al. , 2008 ; Levac et al. , 2009 ; Campbell et al. , 2011 ). Brien et al. ( 2010 ) commented that scoping reviews were ‘often misinterpreted to be a less rigorous systematic review, when in actual fact they are a different entity’.

Some reviews were conducted as stand-alone projects while others were undertaken as parts of larger research projects. Study authors reported that a main purpose or objective for the majority of articles (97.4%; 335/344) was to identify, characterize, and summarize research evidence on a topic, including identification of research gaps. Only 6.4% (22/344) of included articles conducted the scoping review methodology to identify questions for a systematic review. As response options were not mutually exclusive, some reviews reported multiple purposes and/or objectives. A commissioning source was reported in 31.4% (108/344) of reviews; some reported that they were specifically commissioned to advise a funding body as to what further research should be undertaken in an area (e.g., Arksey et al. , 2002 ; Carr-Hill et al. , 2003 ; Fotaki et al. , 2005 ; Baxter et al. , 2008 ; Williams et al. , 2008 ; Trivedi et al. , 2009 ; Crilly et al. , 2010 ; Brearley et al. , 2011 ).

The majority of the included scoping reviews addressed a health topic, making up 74.1% (255/344) of reviews. The use of scoping reviews in software engineering—or ‘systematic mapping’ as termed in the sector—has increased in recent years with 92.7% (38/41) published after 2010. The topics examined in the included scoping reviews ranged greatly, spanning from data on multiplayer online role-playing games (Meredith et al. , 2009 ), to factors that influence antibiotic prophylaxis administration (Gagliardi et al. , 2009 ). The topics investigated were generally broad in nature, such as ‘what is known about the diagnosis, treatment and management of obesity in older adults’ (Decaria et al. , 2012 ). Some reviews that were conducted under short time frames (e.g., 1 month) addressed more specific questions such as ‘what is the published evidence of an association between hospital volume and operative mortality for surgical repair (open and endovascular) of unruptured and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms?’ (Healthcare Improvement Scotland, 2011 ).

3.3. Methodological characteristics of included scoping reviews

The methodological characteristics of included scoping reviews are reported in Table Table2. 2 . Approximately half of the reviews (50.6%; 174/344) reported using one or more methodological frameworks for carrying out the scoping review. Framework use varied greatly between reviews from different sectors, such as in 85.4% (35/41) of reviews from the software engineering sector and in 44.0% (89/202) of health sector reviews. Overall, the Arksey and O'Malley ( 2005 ) framework was the most frequently used, reported in 62.6% (109/174) of studies that reported using a framework. Among reviews from the software engineering sector that reported using a framework, frameworks by Kitchenham and Charters ( 2007 ) (40.0%; 14/35) and Petersen et al . ( 2008 ) (51.4%; 18/35) were most commonly employed. The use of a framework increased over time, from 31.6% (6/19) of reviews published from 2000 to 2004, to 42.5% (37/87) of reviews from 2005 to 2009, and to 55.3% (131/237) of reviews published from 2010 onward.

Methodological characteristics of included reviews ( n = 344)

Following the search, 79.7% (174/344) of reviews used defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen out studies that were not relevant to the review question(s). Among these, only six reviews explicitly reported that criteria were redefined or amended on a post hoc basis during the review process (While et al. , 2005 ; Marsella, 2009 ; Crooks et al. , 2010 ; Johnston et al. , 2010 ; Snyder et al. , 2011 ; Victoor et al. , 2012 ). The selection criteria in a few reviews were unclear due to ambiguous wording such as ‘real paper’ (Saraiva et al. , 2012 ), ‘scientific papers’ (Victoor et al. , 2012 ), and ‘culling low-interest articles’ (Catts et al. , 2010 ). Compared with the study selection process, fewer details were generally reported about the data characterization (or charting) of individual studies. Nearly a quarter of reviews (23.8%; 82/344) did not report any detail as to how the included studies were characterized, and it was unclear in 33.4% (115/344) as to how many reviewers were involved.

The majority of included reviews (77.7%, 267/344) did not assess the methodological quality of individual studies. A number of these studies reported that quality assessment was not conducted as it is not a priority in scoping reviews or part of the scoping review methodology. Two studies reported the use of publication in a peer-reviewed publication as a proxy for good quality (Baxter et al. , 2008 ; Pita et al. , 2011 ) and another reported using studies included in existing reviews or meta-analyses to ‘overcome’ the lack of quality assessment (MacDougall, 2011 ). Of the 22.4% (77/344) of articles that reported a critical appraisal step, the rigor with which it was conducted ranged from the reviewer's subjective assessment using a scale of high, medium, or low (Roland et al. , 2006 ), to the use of published tools such as the Jadad scale (Jadad et al. , 1996 ) for randomized control trials (Deshpande et al. , 2009 ; Borkhoff et al. , 2011 ).

The level of detail reported about the search strategy varied considerably across the reviews. Table Table3 3 displays information about the search strategy reported in the included reviews by time. Overall, the detail of reporting for the search increased numerically over time. For example, 78.06% of reviews published after 2009 reported complete strings or a complete list of search terms, compared with 57.89% of reviews published between 2000 and 2004 and 67.82% of reviews published between 2005 and 2009.

Search strategy details reported in included reviews, by year

Table Table4 4 summarizes how some of the results of the included reviews were reported and ‘charted’. A flow diagram was used to display the flow of articles from the initial search to final selection in 35.8% of reviews (123/344). Characteristics of included studies were often displayed in tables (82.9%; 285/344), ranging from basic tables that described the key characteristics of each included study, to cross-tabulation heat maps that used color-coding to highlight cell values. Study characteristics were also mapped graphically in 28.8% (99/344) of reviews, often in the form of histograms, scatterplots, or pie charts. Reviews from the software engineering sector frequently used bubble charts to map the data (Figure (Figure2 2 is an example of a bubble chart). In summarizing the reviewed literature, 77.6% (267/344) of reviews noted gaps where little or no research had been conducted, and 77.9% (268/344) recommended topics or questions for future research.

Reporting of results the included scoping reviews

Bubble plot of scoping reviews published by year and sector. The size of a bubble is proportional to the number of scoping reviews published in the year and sector corresponding to the bubble coordinates.

Stakeholder consultation is an optional sixth-step in the Arksey and O'Malley ( 2005 ) framework and was reported in 39.8% (137/344) of reviews. This optional step was reported in 34.9% (38/109) of reviews that used the Arksey and O'Malley framework, compared with 42.13% (99/235) of reviews that did not. Stakeholders were most often consulted at the search phase to assist with keyword selection for the search strategy or help identify potential studies to include in the review (74.5%; 102/137). Stakeholders were less frequently involved in the interpretation of research findings (30.7%; 42/137) and in the provision of comments at the report writing stage (24.1%; 33/137). Ongoing interaction with stakeholders throughout the review process was reported in 25.9% (89/344) of all reviews. Comparing between sectors, the proportion of reviews that reported consulting with stakeholders was highest in the social sciences sector (71.4%; 10/14) and lowest in the software engineering sector (2.4%; 1/41).

3.4. Reported challenges and limitations

Limitations in the study approach were reported in 71.2% (245/344) of reviews. The most frequent limitation reported in the reviews was the possibility that the review may have missed some relevant studies (32.0%; 110/344). This limitation was frequently attributed to database selection (i.e., searching other databases may have identified additional relevant studies), exclusion of the gray literature from the search, time constraints, or the exclusion of studies published in a language other than English. In comparison with systematic reviews, one review noted that it was ‘unrealistic to retrieve and screen all the relevant literature’ in a scoping review due to its broader focus (Gentles et al. , 2010 ), and a few noted that all relevant studies may not have been identified as scoping reviews are not intended to be as exhaustive or comprehensive (Cameron et al. , 2008 ; Levac et al. , 2009 ; Boydell et al. , 2012 ).

The balance between breadth and depth of analysis was a challenge reported in some reviews. Brien et al. ( 2010 ) and Cronin de Chavez et al . ( 2005 ) reported that it was not feasible to conduct a comprehensive synthesis of the literature given the large volume of articles identified in their reviews. Depth of analysis was also reported to be limited by the time available to conduct the review (Freeman et al. , 2000 ; Gulliford et al. , 2001 ; Templeton et al. , 2006 ; Cahill et al. , 2008 ; Bostock et al. , 2009 ; Brodie et al. , 2009 ).

The lack of critical appraisal of included studies was reported as a study limitation in 16.0% (55/344) of reviews. One review commented that this was the primary limitation of scoping reviews (Feehan et al. , 2011 ), and others noted that without this step, scoping reviews cannot identify gaps in the literature related to low quality of research (Hand and Letts, 2009 ; Brien et al. , 2010 ). Additionally, two reviews reported that their results could not be used to make recommendations for policy or practice because they did not assess the quality of included studies (Bostrom et al. , 2011 ; Churchill et al. , 2011 ). Conversely, Njelesani et al . ( 2011 ) noted that ‘by not addressing the issues of quality appraisal, this study dealt with a greater range of study designs and methodologies than would have been included in a systematic review’, and McColl et al. ( 2009 ) commented that ‘the emphasis of a scoping study is on comprehensive coverage, rather than on a particular standard of evidence’.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we provided an overview of scoping reviews identified in the gray and published literature. Our search for scoping reviews in the published and gray literature aimed to be comprehensive while also balancing practicality and available resources. It was not within the remit of this scoping review to assess the methodological quality of individual scoping reviews included in the analysis. Based on the characteristics, range of methodologies and reported challenges in the included scoping reviews, we have proposed some recommendations for advancing the scoping review approach and enhancing the consistency with which they are undertaken and reported.

4.1. Overview of included scoping reviews

Our results corroborate that scoping reviews are a relatively new approach that has gained momentum as a distinct research activity in recent years. The identified reviews varied in terms of terminology, purpose, methodological rigor, and level of detail of reporting; therefore, there appears to be a lack of clarity or agreement around the appropriate methodology for scoping reviews. In a scoping review that reviewed 24 scoping reviews from the nursing literature, Davis et al. ( 2009 ) also reported that the included scoping reviews varied widely in terms of intent, procedural, and methodological rigor. Given that scoping reviews are a relatively new methodology for which there is not yet a universal study definition, definitive procedure or reporting guidelines, the variability with which scoping reviews have been conducted and reported to date is not surprising. However, efforts have been made by scoping review authors such as Arksey and O'Malley ( 2005 ); Anderson et al. ( 2008 ); Davis et al. ( 2009 ); Brien et al. ( 2010 ); Levac et al. ( 2010 ) and Daudt et al. ( 2013 ) to guide other researchers in undertaking and reporting scoping reviews, as well as clarifying, enhancing, and standardizing the methodology. Their efforts seem to be having some impact given the increase in the number of scoping reviews disseminated in the published and gray literature, the growth in the use of a methodological framework, and the greater amount of detail and consistency with which scoping review processes have been reported.

4.2. Recommendations

Levac et al. ( 2010 ) remarked that discrepancies in nomenclature between ‘scoping reviews’, ‘scoping studies’, ‘scoping literature reviews’, ‘scoping exercises’, and so on lead to confusion, and consequently used the term ‘scoping study’ for consistency with the Arksey and O'Malley framework. We agree that there is a need for consistency in terminology; however, we argue that the term ‘scoping review’ should be adopted in favor of ‘scoping study’ or the other terms that have been used to describe the method. Our review has found that ‘scoping review’ is the most commonly used term in the literature to denote the methodology and that a number of the other terms (i.e., scoping study, scoping exercise, and systematic mapping) have been used to describe a variety of primary research study designs. Furthermore, we find that the word ‘review’ more explicitly indicates that the term is referring to a type of literature review, compared with ‘study’ or ‘exercise’.

As scoping reviews share many of the same processes with the more commonly known systematic review, many of the included reviews compared and contrasted the two methods. We concur with Brien et al. ( 2010 ) that scoping reviews are often misinterpreted as a less rigorous version of a systematic review, when in fact they are a ‘different entity’ with a different set of purposes and objectives. We contend that researchers adopting a systematic review approach but with concessions in rigor to shorten the timescale, refer to the process as a ‘rapid review’. Scoping reviews are one method among many available to reviewing the literature (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ), and researchers need to consider their research question or study purpose when deciding which review approach is most appropriate. Additionally, given that some of the included reviews took over 1 year to complete, we agree that it would be wrong to necessarily assume that scoping reviews represent a quick alternative to a systematic review (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ).

There is an ongoing deliberation in the literature regarding the need for quality assessment of included studies in the scoping review process. While Arksey and O'Malley stated that ‘quality assessment does not form part of the scoping (review) remit’, they also acknowledged this to be a limitation of the method. This may explain why quality assessment was infrequently performed in the included reviews and why it was reported as a study limitation among a number of these reviews. In their follow-up recommendations to the Arksey and O'Malley framework, Levac et al. ( 2010 ) did not take a position on the matter but recommended that the debate on the need for quality assessment continue. However, a recent paper by Daudt et al. ( 2013 ) asserts that it is a necessary component of scoping reviews and should be performed using validated tools. We argue that scoping reviews should include all relevant literature regardless of methodological quality, given that their intent is to present an overview of the existing literature in a field of interest without synthesizing evidence from different studies (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ). In doing so, scoping reviews can provide a more complete overview of all the research activity related to a topic. However, we also recognize that some form of quality assessment of all included studies would enable the identification of gaps in the evidence base—and not just where research is lacking—and a better determination of the feasibility of a systematic review. The debate on the need for quality assessment should consider the challenges in assessing quality among the wide range of study designs and large volume of literature that can be included in scoping reviews (Levac et al. , 2010 ).

The lack of consistency among the included reviews was not surprising given the lack of a universal definition or purpose for scoping reviews (Anderson et al. , 2008 ; Davis et al. , 2009 ; Levac et al. , 2010 ; Daudt et al. , 2013 ). The most commonly cited definition scoping reviews may be the one set forth by Mays et al . ( 2001 ) and used by Arksey and O'Malley: ‘scoping studies aim to map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available and can be undertaken as standalone projects in their own right, especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed extensively before’. However, we believe that a recently proposed definition by Daudt et al . ( 2013 ) is more straightforward and fitting of the method: ‘scoping studies aim to map the literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts; gaps in the research; and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and research’. While we would replace the term ‘scoping studies’ with ‘scoping reviews’, we endorse the Daudt et al . definition because it clearly articulates that scoping reviews are a type of literature review and removes the emphasis away from being ‘rapid’ process.

It has been suggested that the optimal scoping review is ‘one that demonstrates procedural and methodological rigor in its application’ (Davis et al. , 2009 ). We found that some scoping reviews were not reported in sufficient detail to be able to demonstrate ‘rigor in its application’. When there is a lack of clarity or transparency relating to methodology, it is difficult to distinguish poor reporting from poor design. We agree that it is crucial for scoping review authors to clearly report the processes and procedures undertaken—as well as any limitations of the approach—to ensure that readers have sufficient information to determine the value of findings and recommendations (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Davis et al. , 2009 ). The development of reporting guidelines for scoping reviews would help to ensure the quality and transparency of those undertaken in the future (Brien et al. , 2010 ). Given that reporting guidelines do not currently exist for scoping reviews (Brien et al. , 2010 ), researchers conducting scoping reviews may want to consider using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( http://prisma-statement.org/ ) as a guide, where applicable.

4.3. Strengths and limitations of this scoping review

This scoping review used rigorous and transparent methods throughout the entire process. It was guided by a protocol reviewed by a research team with expertise in knowledge synthesis and scoping reviews. To ensure a broad search of the literature, the search strategy included four electronic bibliographic databases, the reference list of eighteen different articles, two internet search engines, the websites of relevant organizations, and the snowball technique. The relevance screening and data characterization forms were pretested by all reviewers and revised as needed prior to implementation. Each citation and article was reviewed by two independent reviewers who met in regular intervals to resolve conflicts. Our use of a bibliographic manager (RefWorks) in combination with systematic review software (DistillerSR) ensured that all citations and articles were properly accounted for during the process. Furthermore, an updated search was performed in October 2012 to enhance the timeliness of this review.

This review may not have identified all scoping reviews in the published and gray literature despite attempts to be as comprehensive as possible. Our search algorithm included nine different terms previously used to describe the scoping process; however, other terms may also exist. Although our search included two multidisciplinary databases (i.e., Scopus, Current Contents) and Google, the overall search strategy may have been biased toward health and sciences. Searching other bibliographic databases may have yielded additional published scoping reviews. While our review included any article published in English, French or Spanish, our search was conducted using only English terms. We may have missed some scoping reviews in the gray literature as only the first 100 hits from each Web search were screened for inclusion. Furthermore, we did not contact any researchers or experts for additional scoping reviews we may have missed.

Other reviewers may have included a slightly different set of reviews than those included in this present review. We adopted Arksey and O'Malley's definition for scoping reviews at the outset of the study and found that their simple definition was generally useful in guiding study selection. However, we encountered some challenges during study selection with reviews that also reported processes or definitions more typically associated with narrative, rapid or systematic reviews. We found that some reviews blurred the line between narrative and scoping reviews, between scoping and rapid reviews, and between scoping and systematic reviews. Our challenges echoed the questions: ‘where does one end and the other start?’ (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ) and ‘who decides whether a particular piece of work is a scoping (review) or not?’ (Anderson et al. , 2008 ). For this review, the pair of reviewers used their judgment to determine whether each review as a whole sufficiently met our study definition of a scoping review. On another note, characterization and interpretation of the included reviews were also subject to reviewer bias.

5. Conclusions