About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Stanford Innovation and Entrepreneurship Certificate

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

New Leaders: A New Paradigm in Educational Leadership

Learning objective.

- analyze the strategy of changing a successful existing program in an established organization to create a model that is more scalable and financially sustainable

- consider the opportunities and challenges of a partnership to scale impact

- understand a variety of revenue models for social impact organizations

- unpack common trade-offs and tensions between financial sustainability, efficacy and scale; and identify conditions and strategic choices that can support organizations maximize financial sustainability, efficacy and scale.

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Firsthand (Vault)

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, strategy and strategic leadership in education: a scoping review.

- 1 Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Research Centre for Human Development, Porto, Portugal

- 2 Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal

Strategy and strategic leadership are critical issues for school leaders. However, strategy as a field of research has largely been overlooked within the educational leadership literature. Most of the theoretical and empirical work on strategy and strategic leadership over the past decades has been related to non-educational settings, and scholarship devoted to these issues in education is still minimal. The purpose of this scoping review was to provide a comprehensive overview of relevant research regarding strategy and strategic leadership, identifying any gaps in the literature that could inform future research agendas and evidence for practice. The scoping review is underpinned by the five-stage framework of Arksey and O’Malley . The results indicate that there is scarce literature about strategy and that timid steps have been made toward a more integrated and comprehensive model of strategic leadership. It is necessary to expand research into more complex, longitudinal, and explanatory ways due to a better understanding of these constructs.

Introduction

Strategy and strategic leadership are critical issues for school leaders ( Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ; Eacott, 2010a ; Eacott, 2011 ). However, strategy as a field of research has largely been overlooked in educational leadership literature ( Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ). Most of the theoretical and empirical work on strategy and strategic leadership over the past decades has been related to non-educational settings, and scholarship devoted to these issues in education is still very limited ( Cheng, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ; Chan, 2018 ).

The concept of strategy appeared in educational management literature in the 1980s; however, little research was produced until the 1990s (cf. Eacott, 2008b ). Specific educational reforms led to large amounts of international literature mostly devoted to strategic planning ( Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Eacott, 2011 ). For a long period, the concept of strategy was incomplete and confusing. The word “strategy” was often used to characterize different kinds of actions, namely, to weight management activities, to describe a high range of leadership activities, to define planning, or to report to individual actions within an organization ( Eacott, 2008a ).

Strategy and strategic planning became synonymous ( Eacott, 2008b ). However, strategy and planning are different concepts, with the strategy being more than the pursuit of a plan ( Davies, 2003 , Davies, 2006 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Quong and Walker, 2010 ). Both phases of plans’ design and plans’ implementation are related, and the quality of this second phase highly depends on planning’ quality ( Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2007 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Eacott, 2011 ; Meyers and VanGronigen, 2019 ). Planning and acting are related and must emerge from the strategy. As stated by Bell (2004) .

Planning based on a coherent strategy demands that the aims of the school are challenged, that both present and future environmental influences inform the development of the strategy, that there should be a clear and well-articulated vision of what the school should be like in the future and that planning should be long-term and holistic (p. 453).

Therefore, it is necessary to adopt a comprehensive and holistic framework of strategy, considering it as a way of intentionally thinking and acting by giving sense to a specific school vision or mission ( Davies, 2003 , 2006 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Quong and Walker, 2010 ).

The works of Davies and colleagues ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ) and Eacott (2008a , 2008b) , Eacott (2010a , 2011) were essential and contributed to a shift in the rationale regarding strategy by highlighting a more integrative and alternate view. Davies and colleagues ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ) developed a comprehensive framework for strategically focused schools , comprising strategic processes, approaches, and leadership. In this model, the strategy is conceptualized as a framework for present and future actions, sustained by strategic thinking about medium to long term goals, and aligned to school vision or direction.

Strategic leadership assumes necessarily a relevant role in strategically focused schools. Eacott (2006) defines strategic leadership as “leadership strategies and behaviors relating to the initiation, development, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of strategic actions within an educational institution, taking into consideration the unique context (past, present, and future) and availability of resources, physical, financial and human” (p. 1). Thereby, key elements of strategic leadership can be identified as one that: 1) acts in a proactive way to contextual changes; 2) leads school analysis and response to changing environment; 3) leads planning and action for school effectiveness and improvement in face of contextual challenges and; 4) leads monitoring and evaluation processes to inform decision making strategically ( Cheng, 2010 ). This brings to the arena a complex and dynamic view of strategic leadership as it is a complex social activity that considers important historical, economic, technological, cultural, social, and political influences and challenges ( Eacott, 2011 ).

Along with these authors, this paper advocates a more comprehensive and contextualized view of strategy and strategic leadership, where strategy is the core element of any leadership action in schools ( Davies and Davies, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ). Here, strategic leadership is not seen as a new theory, but an element of all educational leadership and management theories ( Davies and Davies, 2010 ). Even so, these concepts can inform and be informed by diverse leadership theories, a strategy-specific framework is needed in the educational field.

Considering all the above, strategy can be identified as a topic that is being researched in education, in the recent decades. Nonetheless, there is still scarce educational literature about this issue ( Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ; Cheng, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ; Chan, 2018 ). After 10 years of Eacott’s analysis of literature on strategy in education, it seems that this educational construct is being overlooked as there is still no consensual definition of strategy, different studies are supported in diverse conceptual frameworks and empirical studies about this topic are scarce ( Cheng, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ; Chan, 2018 ). Moreover, despite the interest of a multidisciplinary vision of strategy and strategic leadership, we agree with Eacott (2008b) about the need for a meaningful definition of strategy and strategic leadership in education, as it is a field with its specifications. Hence, research is needed for a clear definition of strategy, an integrated and complete framework for strategic action, a better identification of multiple dimensions of strategy and a comprehensive model of strategic leadership that has strategic thinking and action as core elements for schools improvement (e.g., Eacott, 2010a ; Hopkins et al., 2014 ; Reynolds et al., 2014 ; Harris et al., 2015 ; Bellei et al., 2016 ). This paper aims to contribute to the field offering a scoping review on strategy and strategic leadership in the educational field.

A clear idea of what strategy and strategic leadership mean and what theory or theories support it are of great importance for research and practice. This scoping review is an attempt to contribute to a strategy-specific theory by continuing to focus on ways to appropriately develop specific theories about strategy and strategic leadership in the educational field, particularly focusing on school contexts.

This study is a scoping review of the literature related to strategy and strategic leadership, which aims to map its specific aspects as considered in educational literature. Scoping reviews are used to present a broad overview of the evidence about a topic, irrespective of study quality, and are useful when examining emergent areas, to clarify key concepts or to identify gaps in research (e.g., Arksey and O’Malley, 2005 ; Peters et al., 2015 ; Tricco et al., 2016 ). Since in the current study we wanted to explore and categorize, but not evaluate, information available concerning specific aspects of strategy in educational literature, we recognize that scoping review methodology serves well this purpose.

In this study, Arksey and O’Malley (2005) five-stage framework for scoping reviews, complemented by the guidelines of other authors ( Levac et al., 2010 ; Colquhoun et al., 2014 ; Peters et al., 2015 ; Khalil et al., 2016 ), was employed. The five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s framework are 1) identifying the initial research questions, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. In the sections below, the process of this scoping review is presented.

Identifying the Initial Research Questions

The focus of this review was to explore key aspects of strategy and strategic leadership in educational literature. The primary question that guided this research was: What is known about strategy and strategic leadership in schools? This question was subdivided into the following questions: How should strategy and strategic leadership in schools be defined? What are the main characteristics of strategic leadership in schools? What key variables are related to strategy and strategic leadership in schools?

Identifying Relevant Studies

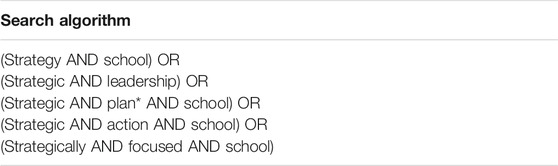

As suggested by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) , keywords for the search were defined, and databases were selected. Key concepts and search terms were developed to capture literature related to strategy and strategic leadership in schools, considering international perspectives. The linked descriptive key search algorithm that was developed to guide the search is outlined in Table 1 .

TABLE 1 . Key search algorithm.

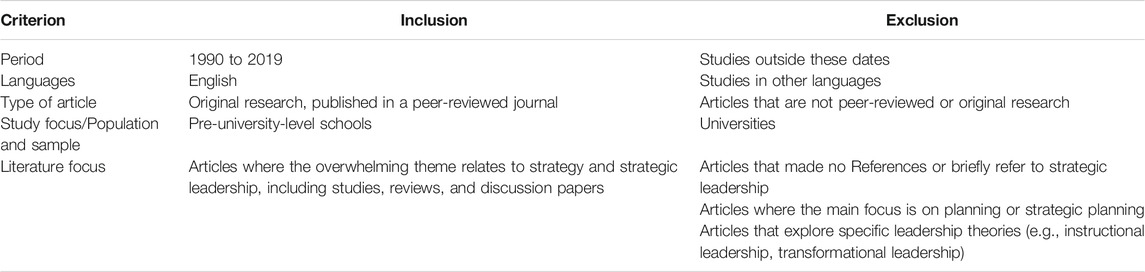

Considering scoping review characteristics, time and resources available, inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed. Papers related to strategy and strategic leadership, published between 1990 and 2019, were included. Educational literature has reported the concepts of strategy and strategic leadership since the 1980s ( Eacott, 2008a ; 2008b ). However, it gained expansion between 1990 and 2000 with studies flourishing mostly about strategic planning ( Eacott, 2008b ). Previous research argues that strategy is more than planning, taking note of the need to distinguish the concepts. Considering our focus on strategy and strategic leadership, studies about strategic planning were excluded as well as papers specifically related to other theories of leadership than strategic leadership. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is outlined in Table 2 .

TABLE 2 . Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The following six electronic databases were searched to identify peer-reviewed literature: ERIC, Education Source, Academic Search Complete, Science Direct, Emerland, and Web of Science. Additionally, a manual search of the reference lists of identified articles was undertaken, and Google Scholar was utilized to identify any other primary sources. The review of the literature was completed over 2 months, ending in August 2019.

Study Selection

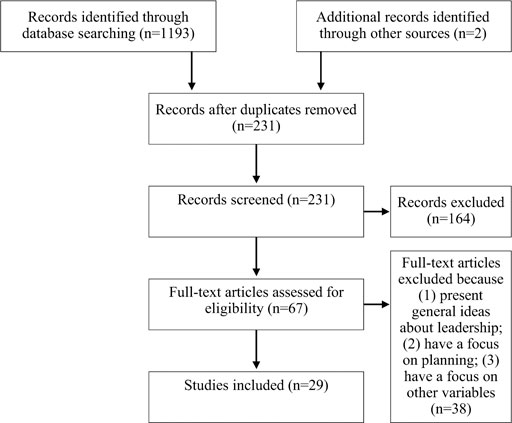

The process of studies’ selection followed the Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement ( Moher et al., 2009 ). Figure 1 illustrates the process of article selection.

FIGURE 1 . PRISMA chart outlining the study selection process.

With the key search descriptors, 1,193 articles were identified. A further number of articles were identified using Google Scholar. However, a large number of articles were removed from the search, as they were duplicated in databases, and 231 studies were identified as being relevant.

The next phases of studies’ selection were guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented above. A screening of the titles, keywords, and abstracts revealed a large number of irrelevant articles, particularly those related to strategic planning (e.g., Agi, 2017 ) and with general ideas about leadership (e.g., Corral and Gámez, 2010 ). Only 67 studies were selected for full-text access and analyses.

Full-text versions of the 67 articles were obtained, with each article being reviewed and confirmed as appropriate. This process provided an opportunity to identify any further additional relevant literature from a review of the reference lists of each article (backward reference search; n = 2). Ultimately, both with database search and backward reference search, a total of 29 articles were included to be analyzed in the scoping review, considering inclusion and exclusion criteria. During this process of study selection, several studies were excluded. As in the previous phase, examples of excluded papers include studies related to strategic planning where the focus is on the planning processes (e.g., Bennett et al., 2000 ; Al-Zboon and Hasan, 2012 ; Schlebusch and Mokhatle, 2016 ) or with general ideas about leadership (e.g., FitzGerald and Quiñones, 2018 ). Additionally, articles that were primarily associated with other topics or related to specific leadership theories (e.g., instructional leadership, transformational leadership) and that only referred briefly to strategic leadership were excluded (e.g., Bandur, 2012 ; Malin and Hackmann, 2017 ). Despite the interest of all these topics for strategic action, we were interested specifically in the concepts of strategy, strategic leadership, and its specifications in educational literature.

Data Charting and Collation

The fourth stage of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) scoping review framework consists of charting the selected articles. Summaries were developed for each article related to the author, year, location of the study, participants, study methods, and a brief synthesis of study results related to our research questions. Details of included studies are provided in the table available in Supplementary Appendix S1 .

Summarising and Reporting Findings

The fifth and final stage of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) scoping review framework summarises and reports findings as presented in the next section. All the 29 articles were studied carefully and a content analysis was taken to answer research questions. Research questions guided summaries and synthesis of literature content.

In this section, results are presented first with a brief description of the origin and nature of the studies, and then as answering research questions previously defined.

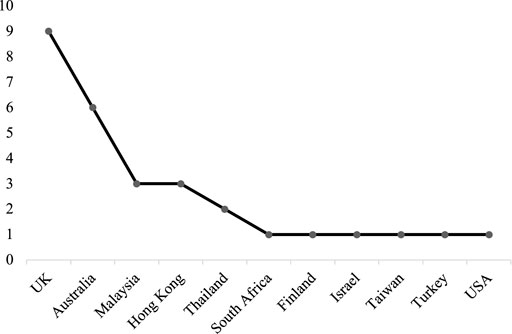

This scoping review yielded 29 articles, specifically devoted to strategy and strategic leadership in education, from eleven different countries (cf. Figure 2 ). The United Kingdom and Australia have the highest numbers of papers. There is a notable dispersion of literature in terms of geographical distribution.

FIGURE 2 . Number of papers per country.

A large number of these articles were published by Brent Davies and colleagues ( N = 9) and Scott Eacott ( N = 6). Without question, these authors have influenced and shaped the theoretical grounding about strategy and strategic leadership in educational literature. While Davies and colleagues have contributed to design a framework of strategy and strategic leadership, influencing the emergence of other studies related to these topics, Eacott provided an essential contribution by exploring, systematizing, and problematizing the existing literature about these same issues. The other authors have published between one and two papers about these topics.

Seventeen papers are of conceptual or theoretical nature, and twelve are empirical research papers (quantitative methods–7; qualitative methods–4; mixed methods–1). The conceptual/theoretical papers analyze the concepts of strategy and strategic leadership, present a framework for strategic leadership, and discuss implications for leaders’ actions. The majority of empirical studies are related to the skills, characteristics, and actions of strategic leaders. Other empirical studies explore relations between strategic leadership and other variables, such as collaboration, culture of teaching, organizational learning, and school effectiveness.

How should Strategy and Strategic Leadership in Schools be Defined?

The concept of strategy is relatively new in educational literature and, in great part, related to school planning. In this scoping review, a more integrated and comprehensive view is adopted ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies, 2006 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Quong and Walker, 2010 ). Davies (2003) defined strategy as a specific pattern of decisions and actions taken to achieve an organization’s goals (p. 295). This concept of strategy entails some specific aspects, mainly that strategy implies a broader view incorporating data about a specific situation or context ( Davies, 2003 ; Dimmock and Walker, 2004 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2007 ). It is a broad organizational-wide perspective , supported by a vision and direction setting , that conceals longer-term views with short ones ( Davies, 2003 ; Dimmock and Walker, 2004 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2007 ). It can be seen as a template for short-term action . However, it deals mostly with medium-and longer-term views of three-to 5-year perspectives ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2007 ). In this sense, a strategy is much more a perspective or a way of thinking that frames strategically successful schools ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies and Davies, 2005 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ).

Eacott (2008a) has argued that strategy in the educational leadership context is a field of practice and application that is of a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary nature. More than a single definition of strategy, what is needed is a conceptual understanding and articulation of its fundamental features, which removes the need to answer, “what is a strategy?” Understanding strategy as choosing a direction within a given context, through leadership, and articulating that direction through management practices ( Eacott, 2008a , p. 356) brings to the arena diverse elements of strategy from both leadership and management. From this alternative point of view, a strategy may be seen as leadership ( Eacott, 2010a ). More than an answer to “what is a strategy?”, it is crucial to understand “when and how does the strategy exist?” ( Eacott, 2010a ), removing the focus on leaders’ behaviors and actions per se to cultural, social, and political relationships ( Eacott, 2011 ). Hence, research strategy and strategic leadership oblige by acknowledging the broader educational, societal, and political contexts ( Dimmock and Walker, 2004 ; Eacott, 2010a ; Eacott, 2010b ; Eacott, 2011 ).

Strategic leadership is a critical component of school development ( Davies and Davies, 2006 ). However, to define leadership is challenging considering the amount of extensive, diverse literature about this issue. Instead of presenting a new categorization about leadership, the authors most devoted to strategic leadership consider it as a key dimension of any activity of leadership ( Davies and Davies, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Eacott, 2010a ; Eacott, 2010b ; Eacott, 2011 ). Barron et al. (1995) stressed the idea of change. As mentioned by the authors, implementation of strategic leadership means change: change in thinking, change in the way schools are organized, change in management styles, change in the distribution of power, change in teacher education programs, and change in roles of all participants ( Barron et al., 1995 , p. 180). Strategic leadership is about creating a vision, setting the direction of the school over the medium-to longer-term and translating it into action ( Davies and Davies, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ). In that sense, strategic leadership is a new way of thinking ( Barron et al., 1995 ) that determines a dynamic and iterative process of functioning in schools ( Eacott, 2008b ).

In their model of strategic leadership, Davies and Davies (2006) consider that leadership must be based on strategic intelligence, summarised as three types of wisdom: 1) people wisdom, which includes participation and sharing information with others, developing creative thinking and motivation, and developing capabilities and competencies within the school; 2) contextual wisdom, which comprises understanding and developing school culture, sharing values and beliefs, developing networks, and understanding external environment; and 3) procedural wisdom, which consists of the continuous cycle of learning, aligning, timing and acting. This model also includes strategic processes and strategic approaches that authors define as the centre of this cycle ( Davies and Davies, 2006 , p. 136).

To deeply understand strategic leadership, it is necessary to explore strategic processes and approaches that leaders take ( Davies and Davies, 2010 ). In this sense, strategic leadership, strategic processes, and strategic approaches are key elements for sustainable and successful schools, which are found to be strategically focused. Davies (2006) designed a model for a strategically focused school that may be defined as one that is educationally effective in the short-term but also has a clear framework and processes to translate core moral purpose and vision into an excellent educational provision that is challenging and sustainable in the medium-to long-term (p.11). This model incorporates 1) strategic processes (conceptualization, engagement, articulation, and implementation), 2) strategic approaches (strategic planning, emergent strategy, decentralized strategy, and strategic intent), and 3) strategic leadership (organizational abilities and personal characteristics). Based on these different dimensions, strategically focused schools have built-in sustainability, develop set strategic measures to assess their success, are restless, are networked, use multi-approach planning processes, build the strategic architecture of the school, are strategically opportunistic, deploy strategy in timing and abandonment and sustain strategic leadership ( Davies, 2004 , pp.22–26).

What Are the Main Characteristics of Strategic Leadership in Schools?

Davies (2003) , Davies and Davies (2005) , Davies and Davies (2006) , Davies and Davies (2010) discuss what strategic leaders do (organizational abilities) and what characteristics strategic leaders display (personal characteristics). The key activities of strategic leaders, or organizational abilities, are 1) create a vision and setting a direction, 2) translate strategy into action, 3) influence and develop staff to deliver the strategy, 4) balance the strategic and the operational, 5) determine effective intervention points ( what, how, when, what not to do and what to give up ), 6) develop strategic capabilities, and 7) define measures of success ( Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ). The main characteristics that strategic leaders display, or their characteristics, are 1) dissatisfaction or restlessness with the present, 2) absorptive capacity, 3) adaptive capacity, and 4) wisdom.

Two specific studies explored the strategic leadership characteristics of Malaysian leaders ( Ali, 2012 ; Ali, 2018 ), considering the above-mentioned model as a framework. For Malaysian Quality National Primary School Leaders, the results supported three organizational capabilities (strategic orientation, translation, and alignment) and three individual characteristics of strategic leadership (dissatisfaction or restlessness with the present, absorptive capacity, and adaptive capacity). For Malaysian vocational college educational leaders, the results were consistent with seven distinct practices of strategic leadership, such as strategic orientation, strategic alignment, strategic intervention, restlessness, absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and leadership wisdom.

Other studies were also focused on the characteristics of strategic leadership with different populations and countries. Chatchawaphun et al. (2016) identified the principles, attributes, and skills of the strategic leadership of secondary school administrators from Thailand. The principles identified within the sample of principals included appropriate values, modern visionary, future focusing strategy, empirical evidence focus, intention toward accomplishment, decency, and making relationships. The attributes found were strategic learning, strategic thinking, and value push up. The skills were learning, interpretation, forecasting, planning, challenge, and decision making. Chan (2018) explored strategic leadership practices performed by Hong Kong school leaders of early childhood education and identified effective planning and management, reflective and flexible thinking, and networking and professional development as variables. Eacott (2010c) investigated the strategic role of Australian public primary school principals concerning the leader characteristics of tenure (referring to the time in years in their current substantive position) and functional track (referring to the time in years spent at different levels of the organizational hierarchy). These demographic variables have moderating effects on the strategic leadership and management of participants. These five studies seem to be outstanding contributions to solidify a framework of strategic leadership and to test it with different populations in different countries.

Additionally, Quong and Walker (2010) present seven principles for effective and successful strategic leaders. Strategic leaders are future-oriented and have a future strategy, their practices are evidence-based and research-led, they get things done, open new horizons, are fit to lead, make good partners and do the “next” right thing—these seven principles of action seem related to the proposal of Davies and colleagues. Both authors highlighted visions for the future, future long-term plans, and plans’ translation into action as important characteristics of strategic leaders.

One other dimension that is being explored in research relates to ethics. Several authors assert that insufficient attention and research have been given to aspects related to moral or ethical leadership among school leaders ( Glanz, 2010 ; Quong and Walker, 2010 ; Kangaslahti, 2012 ). The seventh principle of the Quong and Walker (2010) model of strategic leadership is that leaders do the “next” right thing. This relates to the ethical dimension of leadership, meaning that strategic leaders recognize the importance of ethical behaviors and act accordingly. For some authors, ethics in strategic leadership is a critical issue for researchers and practitioners that needs to be taken into consideration ( Glanz, 2010 ; Quong and Walker, 2010 ). Glanz (2010) underlined social justice and caring perspectives as required to frame strategic initiatives. Kangaslahti (2012) analyzed the strategic dilemmas that leaders face in educational settings (e.g., top-down strategy vs. bottom-up strategy process; leadership by authority vs. staff empowerment; focus on administration vs. focus on pedagogy; secret planning and decision making vs. open, transparent organization; the well-being of pupils vs. well-being of staff) and how they can be tackled by dilemma reconciliation. Chen (2008) , in case study research, explored the conflicts that school administrators have confronted in facilitating school reform in Taiwan. The author identified four themes related to strategic leadership in coping with the conflicts accompanying this school reform: 1) educational values, 2) timeframe for change, 3) capacity building, and 4) community involvement. These studies reinforce the idea that school improvement and success seem to be influenced by the way leaders think strategically and deal with conflicts or dilemmas. Researchers need to design ethical frameworks or models from which practitioners can think ethically about their strategic initiatives and their dilemmas or conflicts ( Chen, 2008 ; Glanz, 2010 ; Kangaslahti, 2012 ).

Despite the critical contribution of Davies’ models ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ) and subsequent works, Eacott (2010a) questions the production of lists of behaviors and traits. This is likely one of the main differences between Davies’ and Eacott’s contributions in this field. While Davies and colleagues include organizational abilities and personal characteristics in their model of strategic leadership, Eacott (2010a , 2010b) emphasizes the broader context where strategy occurs. These ideas, however, are not contradictory but complementary in the comprehension of strategy as leadership in education since both authors present a comprehensive and integrated model of strategic leadership. Even though Davies and colleagues present some specific characteristics of leaders, these characteristics are incorporated into a large model for strategy in schools.

What Are Other Key Variables Related to Strategy and Strategic Leadership in Schools?

Other studies investigated the relationship between strategic leadership and other key variables, such as collaboration ( Ismail et al., 2018 ), the culture of teaching ( Khumalo, 2018 ), organizational learning ( Aydin et al., 2015 ) and school effectiveness ( Prasertcharoensuk and Tang, 2017 ).

One descriptive survey study presented teacher collaboration as a mediator of strategic leadership and teaching quality ( Ismail et al., 2018 ). The authors argue that school leaders who demonstrate strategic leadership practices can lead to the creation of collaborative practices among teachers and thus help to improve the professional standards among them, namely, teaching quality ( Ismail et al., 2018 ). One cross-sectional study identified positive and significant relations among the variables of strategic leadership actions and organizational learning. Transforming, political, and ethical leadership actions were identified as significant predictors of organizational learning. However, managing actions were not found to be a significant predictor ( Aydin et al., 2015 ). One other study establishes that strategic leadership practices promote a teaching culture defined as the commitment through quality teaching for learning outcomes ( Khumalo, 2018 ). These three studies provide essential highlights of the relevance of strategic leadership for school improvement and quality. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that in a research survey that examined the effect of leadership factors of administrators on school effectiveness, the authors concluded that the direct, indirect, and overall effects of the administrators’ strategic leadership had no significant impact on school effectiveness ( Prasertcharoensuk and Tang, 2017 ). These studies introduce important questions that need to be explored both related to strategy and strategic leadership features and its relations and impacts on relevant school variables. Such studies stimulate researchers to explore these and other factors that relate to strategic leadership.

The knowledge about strategy and strategic leadership is still incomplete and confusing ( Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ). From the 29 studies selected, divergent data and multiple concepts of strategy can be identified which reinforces the confusion about these issues. Some integrative clarification is still needed about the concepts of strategy and strategic leadership as about its core features. In this section, it is intended to contribute to the clarification and integration of the concepts considering the studies selected.

The emergence of politics and reforms related to school autonomy and responsibility in terms of efficacy and accountability brings the concept of strategy to the educational literature ( Eacott, 2008b ; Cheng, 2010 ). It first appeared in the 1980s but gained momentum between 1990 and 2000. However, the main focus of the literature was on strategic planning based upon mechanistic or technical-rational models of strategy. Authors have criticized the conceptualization of strategy as a way for elaborating a specific plan of action for schools ( Davies, 2003 ; Davies, 2006 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2008b ; Quong and Walker, 2010 ). These same authors adopted a more comprehensive and holistic model of strategy. The concepts have been developed from a more rational and mechanistic view related to planning processes to a more comprehensive and complex view of strategy and leadership that take into consideration a situated and contextual framework. Considering the contribution of these studies, strategy incorporates three core dimensions, articulated with a schoolwide perspective 1) Vision, mission and direction (e.g., Davies, 2003 ; Dimmock and Walker, 2004 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2007 ; Eacott, 2008a ) 2) Intentional thinking (e.g., Barron et al., 1995 ; Davies, 2003 ; Davies and Davies, 2005 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ): and; 3) Articulated decision-making and action (e.g., Davies, 2003 ; Dimmock and Walker, 2004 ; Davies and Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2006 ; Davies, 2007 ; Eacott, 2008a ; Eacott, 2010a ; Eacott, 2010b ; Eacott, 2011 ).

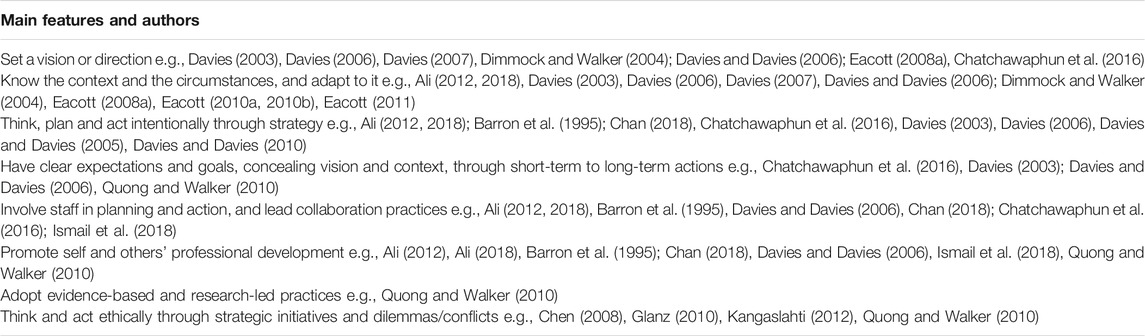

Strategic leaders have an important role in strategy but, even considering this comprehensive and holistic concept of strategy, research poses the question of what are the main characteristics of strategic leaders in schools? From the literature reviewed, specific abilities, behaviors, and other characteristics may be identified. Looking for an integrated picture of strategic leadership, Table 3 represents the main contributions of the studies selected.

TABLE 3 . Strategic leadership: Main features.

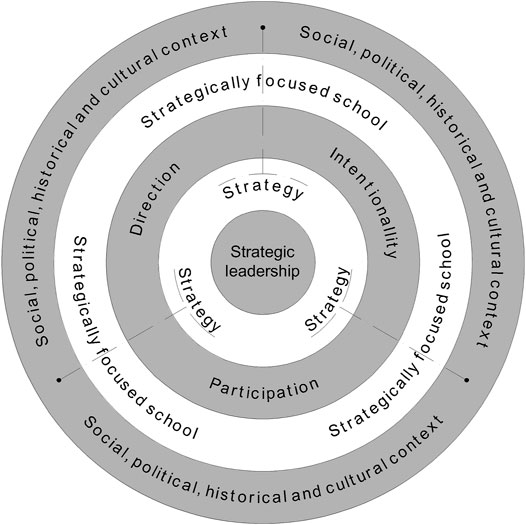

Despite the contribution of these studies to deep knowledge about strategic leadership, the discussion here considers whether it is worthwhile to produce lists of behaviors and traits for strategic leaders in the absence of an integrated model that acknowledges the broader educational, societal and political context ( Dimmock and Walker, 2004 ; Eacott, 2010a ; Eacott, 2010b ; Eacott, 2011 ). Eacott (2011) argues that strategy, as constructed through analysis, is decontextualized and dehumanized and essentially a vacuous concept with limited utility to the practice that it seeks to explain (p. 426). Without a comprehensive and contextual model of strategy and strategic leadership, supported by research, the topics may still be overlooked and misunderstood. With this in mind, Figure 3 attempts to represent the core dimensions of strategy from a comprehensive perspective.

FIGURE 3 . Strategy and core dimensions from a comprehensive perspective.

As this is a scoping review, we tried to display a general view of the literature that can serve as a basis for a specific strategy theory in education and to more in-depth studies related to strategy and strategic leadership in schools. Nevertheless, we need to identify some methodological limitations of this study. As a scoping review, methods and reporting need improvement ( Tricco et al., 2018 ) and we are aware of this circumstance. Also, our search strategy may have overlooked some existing studies, since grey documents (e.g., reports) and studies from diverse languages than English were not included, that can misrepresent important data. Besides, inclusion criteria focused only on studies specifically devoted to strategy (not strategic planning) and strategic leadership (no other theories of leadership), but we acknowledge important contributions from this specific literature that were excluded. Finally, in our study there is no comparative analysis between the western and eastern/oriental contexts. However, we are aware that these contexts really differ and a context-specific reflection on strategy and strategic leadership in education would be useful. More research is needed to overcome the limitations mentioned.

Besides, the pandemic COVID19 brought new challenges in education, and particularly, to leaders. This study occurred before the pandemic and this condition was not acknowledged. However, much has changed in education as a consequence of the pandemic control measures, these changes vary from country to country, and schools’ strategies have changed for sure. Future research needs to explore strategy and strategic leadership in education considering a new era post pandemic.

With this scoping review, the authors aimed to contribute to enduring theories about strategy and strategic leadership in education. From our findings, it appears that this issue is being little explored. Despite the important contributions of authors cited in this scoping review ( Aydin et al., 2015 ; Chatchawaphun et al., 2016 ; Prasertcharoensuk and Tang, 2017 ; Ali, 2018 ; Chan, 2018 ; Ismail et al., 2018 ; Khumalo, 2018 ), minor advances seem to have been made after 2010. This is intriguing taking into account the leaders’ role in the third wave of educational reform, where strategic leadership pursues a new vision and new aims for education due to maximizing learning opportunities for students through “ triplisation in education’ (i.e., as an integrative process of globalization, localization and individualization in education)” ( Cheng, 2010 , p. 48). It was expected that research moved from rational planning models towards a more complex view of strategy in education ( Eacott, 2011 ). This review brings the idea that some timid and situated steps have been made.

Since the important review by Eacott, published in 2008, a step forward was made in the distinction between strategy and planning. Despite the significant number of papers about planning that were found during this review, the majority were published before 2008 (e.g., Nebgen, 1990 ; Broadhead et al., 1998 ; Bennett et al., 2000 ; Beach and Lindahl, 2004 ; Bell, 2004 ). Also, most of the papers selected adopt a more integrative, comprehensive, and complex view of strategy and strategic leadership (e.g., Eacott, 2010a ; Eacott, 2010b ; Davies and Davies, 2010 ; Eacott, 2011 ; Ali, 2012 ; Ali, 2018 ; Chan, 2018 ). More than identifying the “best of” strategy and strategic leadership, alternative models understand strategy as a way of thinking ( Davies and Davies, 2010 ) and a work in progress ( Eacott, 2011 ).

This also resonates with the educational literature about loosely coupled systems . There is evidence that loosely coupled educational organizations continue to exist and that resistance to change is a characteristic of school organizations ( Hautala et al., 2018 ). Strategic leadership gains relevance since leaders need to consider how to manage their loose and tight configurations and, hence, reinforce simultaneous personal and organizational dimensions related to school improvement. It is time to expand the research into more complex, longitudinal, and explanatory ways due to a better understanding of the constructs. This scoping review was an attempt to contribute to this endeavor by integrating and systematizing educational literature about strategy and strategic leadership.

Author Contributions

MC-collected and analyzed data, write the paper IC, JV, and JA-guided the research process and reviewed the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) for the support to this publication (Ref. UIDB/04872/2020).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.706608/full#supplementary-material

Agi, U. (2017). School Development Planning: A Strategic Tool for Secondary School Improvement in Rivers State, Nigeria. J. Int. Soc. Teach. Educ. 21 (1), 88–99.

Google Scholar

Al-Zboon, W., and Hasan, M. (2012). Strategic School Planning in Jordan. Education 132 (4), 809–825.

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8 (1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Aydin, M., Guclu, N., and Pisapia, J. (2015). The Relationship between School Principals’ Strategic Leadership Actions and Organizational Learning. Am. J. Educ. Stud. 7 (1), 5–25.

Bandur, A. (2012). School‐based Management Developments: Challenges and Impacts. J. Educ. Admin 50 (6), 845–873. doi:10.1108/09578231211264711

Barron, B., Henderson, M., and Newman, P. (1995). Strategic Leadership: A Theoretical and Operational Definition. J. Instructional Psychol. 22, 178–181.

Beach, R. H., and Lindahl, R. (2004). A Critical Review of Strategic Planning: Panacea for Public Education?. J. Sch. Leadersh. 14 (2), 211–234. doi:10.1177/105268460401400205

Bell, L. (2004). Strategic Planning in Primary Schools. Manag. Educ. 18 (4), 33–36. doi:10.1177/08920206040180040701

Bellei, C., Vanni, X., Valenzuela, J. P., and Contreras, D. (2016). School Improvement Trajectories: An Empirical Typology. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 27 (3), 275–292. doi:10.1080/09243453.2015.1083038

Bennett, Megan Crawford, Rosalind L, N., Crawford, M., Levačić, R., Glover, D., and Earley, P. (2000). The Reality of School Development Planning in the Effective Primary School: Technicist or Guiding Plan? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 20 (3), 333–351. doi:10.1080/13632430050128354

Broadhead, P., Hodgson, J., Cuckle, P., and Dunford, J. (1998). School Development Planning: Moving from the Amorphous to the Dimensional and Making it Your Own. Res. Pap. Educ. 13 (1), 3–18. doi:10.1080/0267152980130102

Chan, C. W. (2018). Leading Today's Kindergartens. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 46 (4), 679–691. doi:10.1177/1741143217694892

Chatchawaphun, P., Julsuwan, S., and Srisa-ard, B. (2016). Development of Program to Enhance Strategic Leadership of Secondary School Administrators. Ies 9 (10), 34–46. doi:10.5539/ies.v9n10p34

Chen, P. (2008). Strategic Leadership and School Reform in Taiwan. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 19 (3), 293–318. doi:10.1080/09243450802332119

Cheng, Y. (2010). A Topology of Three-Wave Models of Strategic Leadership in Education. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 38 (1), 35–54.

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., et al. (2014). Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. , 67(12), 1291–1294. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Corral Granados, A., and Granados Gámez, G. (2010). Sustainability and Triple Bottom Line: Key Issues for Successful Spanish School Principals. Intl Jnl Educ. Mgt. , 24(6), 467–477.doi:10.1108/09513541011067656

Davies, B. (2004), Developing the Strategically Focused School, Sch. Leadersh. Manag. , 24(1), 11–27. doi:10.1080/1363243042000172796

Davies, B., and Davies, B. J. (2005). Strategic Leadership Reconsidered. Leadersh. Pol. Schools , 4(3), 241–260. doi:10.1080/15700760500244819

Davies, B., and Davies, B. (2010). The Nature and Dimensions of Strategic Leadership. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. , 38(1), 5–21.

Davies, B. (2007). Developing Sustainable Leadership. Manag. Educ. , 21(3), 4–9. doi:10.1177/0892020607079984

Davies, B. J., and Davies, B.(2004), Strategic Leadership, Sch. Leadersh. Manag. , 24(1), 29–38. doi:10.1080/1363243042000172804

Davies, B. J., and Davies, B. (2006). Developing a Model for Strategic Leadership in Schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. , 34(1), 121–139. doi:10.1177/1741143206059542

Davies, B. (2006). Processes Not Plans Are the Key to Strategic Development. Manag. Educ. , 20(2), 11–15. doi:10.1177/089202060602000204

Davies, B. (2003). Rethinking Strategy and Strategic Leadership in Schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. , 31(3), 295–312. doi:10.1177/0263211x03031003006

Dimmock, C., and Walker, A. (2004). A New Approach to Strategic Leadership: Learning‐centredness, Connectivity and Cultural Context in School Design, Sch. Leadersh. Manag. , 24(1), 39–56. doi:10.1080/1363243042000172813

Eacott, S. (2006). Strategy: An Educational Leadership Imperative, Perspect. Educ. Leadersh. , 16(6), 1–12.

Eacott, S. (2008b). An Analysis of Contemporary Literature on Strategy in Education. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. , 11(3), 257–280. doi:10.1080/13603120701462111

Eacott, S. (2010b). Lacking a Shared Vision: Practitioners and the Literature on the Topic of Strategy. J. Sch. Leadersh. , 20, 425–444. doi:10.1177/105268461002000403

Eacott, S. (2011) Leadership Strategies: Re-conceptualising Strategy for Educational Leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. , 31 (1), 35–46. doi:10.1080/13632434.2010.540559

Eacott, S. (2010a). Strategy as Leadership: an Alternate Perspective to the Construct of Strategy. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. , 38(1), 55–65.

Eacott, S. (2008a). Strategy in Educational Leadership: In Search of unity, J. Educ. Admin. , 46(3), 353–375. doi:10.1108/09578230810869284

Eacott, S. (2010c). Tenure, Functional Track and Strategic Leadership. Intl Jnl Educ. Mg.t , 24(5), 448–458. doi:10.1108/09513541011056009

FitzGerald, A. M., and Quiñones, S. (2018). The Community School Coordinator: Leader and Professional Capital Builder. Jpcc , 3(4), 272–286. doi:10.1108/JPCC-02-2018-0008

Glanz, J. (2010). Justice and Caring: Power, Politics, and Ethics in Strategic Leadership. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. , 38(1), 66–86.

Harris, A., Adams, D., Jones, M. S., and Muniandy, V. (2015). System Effectiveness and Improvement: The Importance of Theory and Context. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement , 26(1), 1–3. doi:10.1080/09243453.2014.987980

Hautala, T., Helander, J., and Korhonen, V. (2018). Loose and Tight Coupling in Educational Organizations - an Integrative Literature Review. Jea , 56(2), 236–255. doi:10.1108/JEA-03-2017-0027

Hopkins, D., Stringfield, S., Harris, A., Stoll, L., and Mackay, T. (2014). School and System Improvement: A Narrative State-Of-The-Art Review. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement , 25(2), 257–281. doi:10.1080/09243453.2014.885452

Ismail, S. N., Kanesan, A., Kanesan, A. G., and Muhammad, F. 2018). Teacher Collaboration as a Mediator for Strategic Leadership and Teaching Quality. Int. J. Instruction , 11(4), 485–498. doi:10.12973/iji.2018.11430a

Kangaslahti, J. (2012). Mapping the Strategic Leadership Practices and Dilemmas of a Municipal Educational Organization. Euromentor J. - Stud. about Educ. , 4, 9–17.

Khalil, H., Peters, M., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Soares, C. B., and Parker, D., (2016). An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. , 13(2), 118–123. doi:10.1111/wvn.12144

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Khumalo, S. (2018). Promoting Teacher Commitment through the Culture of Teaching through Strategic Leadership Practices. Gend. Behav. , 16(3), 12167 -12177.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., and O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement Sci. , 5(1), 69–9. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1748-5908-5-69.pdf . doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Malin, J. R., and Hackmann, D. (2017). Urban High School Principals' Promotion of College-And-Career Readiness. Jea , 55(6), 606–623. doi:10.1108/JEA-05-2016-0054

Meyers, C. V., and VanGronigen, B. A. (2019). A Lack of Authentic School Improvement Plan Development, J. Educ. Admin , 57(3), 261–278. doi:10.1108/JEA-09-2018-0154

Mohd Ali, H. b., and Zulkipli, I. B. (2019). Validating a Model of Strategic Leadership Practices for Malaysian Vocational College Educational Leaders. Ejtd 43, 21–38. doi:10.1108/EJTD-03-2017-0022

Mohd Ali, H. (2012). The Quest for Strategic Malaysian Quality National Primary School Leaders. Intl Jnl Educ. Mgt. , 26 (1), 83–98. doi:10.1108/09513541211194392

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. BMJ , 339, b2535–269. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535

Nebgen, M. K. (1990). Strategic Planning: Achieving the Goals of Organization Development. J. Staff Dev. , 11(1), 28–31.doi:10.1108/eum0000000001151

Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Soares, C., Khalil, H., and Parker, D., (2015). Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews . The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual . Adelaide, South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute .

Prasertcharoensuk, T., and Tang, K. N. (2017). The Effect of Strategic Leadership Factors of Administrators on School Effectiveness under the Office of Maha Sarakham Primary Educational Service Area 3. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. , 38(3), 316–323. doi:10.1016/j.kjss.2016.09.001

Quong, T., and Walker, A. (2010). Seven Principles of Strategic Leadership. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. , 38(1), 22–34.

Reynolds, D., Sammons, P., De Fraine, B., Van Damme, J., Townsend, T., Teddlie, C., et al. (2014). Educational Effectiveness Research (EER): A State-Of-The-Art Review. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement , 25(2), 197–230. doi:10.1080/09243453.2014.885450

Schlebusch, G., and Mokhatle, M. (2016) Strategic Planning as a Management Tool for School Principals in Rural Schools in the Motheo District. Int. J. Educ. Sci. , 13(3), 342–348. doi:10.1080/09751122.2016.11890470

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., et al. (2016). A Scoping Review on the Conduct and Reporting of Scoping Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. , 16(15), 15–10. doi:10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. 2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. , 169(7), 467–473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

Keywords: strategy, strategic leadership, school leadership, scoping review, education

Citation: Carvalho M, Cabral I, Verdasca JL and Alves JM (2021) Strategy and Strategic Leadership in Education: A Scoping Review. Front. Educ. 6:706608. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.706608

Received: 07 May 2021; Accepted: 23 September 2021; Published: 15 October 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Carvalho, Cabral, Verdasca and Alves. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marisa Carvalho, [email protected]

- Utility Menu

- Professional Development

- Case Studies & Research Notes

PELP case studies illuminate systems-level leadership challenges in large urban districts and education-related organizations. Together with research notes and teaching notes for instructors, the PELP case library is an extensive body of working knowledge for academics and practitioners alike.

- Case Library at HBS Publishing

- Research Notes on Frameworks & Strategy

Case Library at Harvard Ed Press

- Teaching Notes

The Case Library at Harvard Business School Publishing

The following cases are publicly available to access below. For the multimedia cases (PEL-097, PEL-098, PEL-099), when redirected to Harvard Business Press, make a free educator's account, create a coursepack, select "institution pay" (cost remains free), add the multimedia case to the coursepack, add an enrollment number, and publish the coursepack to access the multimedia case link that you can share with students/participants. Harvard Business Publishing can answer additional questions about accessing multimedia cases. For the multimedia cases, printer-friendly accessible versions are available upon request by emailing [email protected] .

- PEL-099: BMore Me: Empowering Youth Through Learning in Baltimore City Schools, Multimedia Case

- PEL-098: The Cure is in the Culture: Systems Change for Black Boys in the Oakland USD, Multimedia Case

- PEL-097: The HR Life Cycle: Human Capital Systems in the Madison Metropolitan School District, Multimedia Case

- PEL-093: Access, Autonomy, and Accountability: School Governance Dilemmas in Post-Katrina New Orleans (B) Case Supplement Note on Governance

- PEL-092: Access, Autonomy, and Accountability: School Governance Dilemmas in Post-Katrina New Orleans (A)

- PEL-091: Baltimore City Public Schools (City Schools): The [Entry] of a New Chief Executive Officer

- PEL-090: Metro Nashville Public Schools (MNPS): The [Entry] of a New Director of Schools

- PEL-089: PLIE: Improving the Capacity of School Leaders in Argentina

- PEL-087: The Nike School Innovation Fund: Scaling for Impact in Oregon Public Schools

- PEL-085: Decentralization in Clark County School District: Strategy is Everyone's Job

- PEL-080: Uncommon Schools (B): Seeking Excellence at Scale through Standardized Practice

- PEL-079: Uncommon Schools (A): A Network of Networks

- PEL-084: Denver Public Schools (B): Innovation and Performance?

- PEL-076: Denver Public Schools 2015 (A): Innovation and Performance?

- PEL-074: Organizing for Family and Community Engagement in the Baltimore City Public Schools

- PEL-073: Between Compliance and Support: The Role of the Commonwealth in District Takeovers

- PEL-071: Career Pathways, Performance Pay, and Peer-Review Promotion in Baltimore City Public Schools

- PEL-070: Baltimore City Public Schools: Implementing Bounded Autonomy (B)

- PEL-063: Baltimore City Public Schools: Implementing Bounded Autonomy (A)

- PEL-068: Central Falls High School

- PEL-067: Meeting New Challenges at the Aldine Independent School District (B)

- PEL-030: Meeting New Challenges at the Aldine Independent School District (A)

- PEL-062: The Parent Academy: Family Engagement in Miami-Dade County Public Schools

- PEL-061: The Turn-Around at Highland Elementary School

- PEL-055: Taking Human Resources Seriously in Minneapolis

- PEL-054: Focusing on Results at the New York City Department of Education

- PEL-053: Managing Schools for High Performance: The Area Instruction Officer at Chicago Public Schools

- PEL-047: Using Data to Improve Instruction at the Mason School

- PEL-044: Race, Accountability, and the Achievement Gap (B)

- PEL-043: Race, Accountability, and the Achievement Gap (A)

- PEL-041: Managing at Scale in the Long Beach Unified School District

- PEL-039: The STAR Schools Initiative at the San Francisco Unified School District

- PEL-033: Managing the Chicago Public Schools

- PEL-029: Reinventing Human Resources at the School District of Philadelphia

- PEL-028: Differentiated Treatment at Montgomery County Public Schools

- PEL-027: Memphis City Schools: The Next Generation of Principals

- PEL-026: New Leadership at Portland Public Schools

- PEL-024: Staffing the Boston Public Schools

- PEL-013: Learning to Manage with Data in Duval County Public Schools: Lake Shore Middle School (B)

- PEL-008: Learning to Manage with Data in Duval County Public Schools: Lake Shore Middle School (A)

- PEL-009: The Campaign for Human Capital at the School District of Philadelphia

- PEL-007: Long Beach Unified School District (B): Working to Sustain Improvement (2002-2004)

- PEL-006: Long Beach Unified School District (A): Change That Leads to Improvement (1992-2002)

- PEL-005: Pursuing Educational Equity at San Francisco Unified School District

- PEL-004: Aligning Resources to Improve Student Achievement: San Diego City Schools (B)

- PEL-003: Aligning Resources to Improve Student Achievement: San Diego City Schools (A)

- PEL-002: Compensation Reform at Denver Public Schools

- PEL-001: Bristol City Schools (BCS)

Research Notes on Frameworks and Strategy

- PEL-096: Note on Racial Equity in School Systems

- PEL-095: Successfully Restarting Schools in the Face of COVID-19: A Framework

- PEL-082: Superintendents of Public School Districts as Sector Level Leaders

- PEL-081: Creating Public Value: School Superintendents as Strategic Managers of Public Schools

- PEL-078: Principals as Innovators: Identifying Fundamental Skills for Leadership of Change in Public Schools

- PEL-083: A Problem-Solving Approach to Designing and Implementing a Strategy to Improve Performance

- PEL-011: Note on Strategy in Public Education

- PEL-010: Note on the PELP Coherence Framework

The following case studies are available for purchase from Harvard Ed Press. If you are interested in receiving the teaching note(s) for the KC-designated cases listed below, please email [email protected] .

- KC37CHA: Challenges to Implementing Innovation and Accountability in Denver

- KC36INVE: Investing in Teachers: The Lawrence Public Schools Respond to State Receivership

- KC39SCAL: Scaling Up Data Wise in Prince George's County Public Schools

- KC40NAV: Navigating Governance Changes and District Improvement: Strategic Leadership in St. Louis Public Schools

- KC41LEAD: Leaders Change, Policies Evolve: The Lawrence Public Schools Respond to State Receivership (Act II)

Teaching Notes (available upon email request)

- PEL-094: Access, Autonomy, and Accountability: School Governance Dilemmas in Post-Katrina New Orleans (A) & (B)

- PEL-088: The Nike School Innovation Fund: Scaling for Impact in Oregon Public Schools

- PEL-086: Denver Public Schools: Innovation and Performance?

- PEL-075: Organizing for Family and Community Engagement in the Baltimore City Public Schools

- PEL-072: Career Pathways, Performance Pay, and Peer-Review Promotion in Baltimore City Public Schools

- PEL-069: Central Falls High School

- PEL-066: Managing Schools for High Performance: The Area Instruction Officer at Chicago Public Schools

- PEL-065: Baltimore City Public Schools: Implementing Bounded Autonomy

- PEL-060: Learning to Manage with Data in Duval County Public Schools: Using the Case in an Education Entrepreneurship Course

- PEL-059: Taking Human Resources Seriously in Minneapolis

- PEL-058: Memphis City Schools: The Next Generation of Principals

- PEL-057: Focusing on Results at the New York City Department of Education

- PEL-052: Southwest Airlines: Using Human Resources for Competitive Advantage (A) - Using the Case with Education Administrators

- PEL-049: Bristol City Schools

- PEL-048: Using Data to Improve Instruction at the Mason School

- PEL-046: Race, Accountability, and the Achievement Gap (A) and (B)

- PEL-042: Managing at Scale in the Long Beach Unified School District

- PEL-040: The STAR Schools Initiative at the San Francisco Unified School District

- PEL-036: Meeting New Challenges at the Aldine Independent School District

- PEL-035: Reinventing Human Resources at the School District of Philadelphia

- PEL-034: Managing the Chicago Public Schools

- PEL-032: New Leadership at Portland Public Schools

- PEL-031: Staffing the Boston Public Schools

- PEL-023: Long Beach Unified School District (B): Working to Sustain Improvement (2002-2004)

- PEL-022: The Campaign for Human Capital at the School District of Philadelphia

- PEL-021: Learning to Manage with Data in Duval County Public Schools: Lake Shore Middle School (A) and (B) Series

- PEL-020: Long Beach Unified School District (A): Change That Leads to Improvement (1992-2002)

- PEL-019: Pursuing Educational Equity at San Francisco Unified School District

- PEL-018: Aligning Resources to Improve Student Achievement: San Diego City Schools Case Series

- PEL-017: Compensation Reform at Denver Public Schools

- PEL-016: Bristol City Schools

- Coherence Framework

- Video Library

- Author Rights

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- JOLE 2023 Special Issue

- Editorial Staff

- 20th Anniversary Issue

- Leadership Education and Experience in the Classroom: A Case Study

Douglas R. Lindsay, Ph. D., Anthony M. Hassan, Ed. D., David V. Day, Ph. D. 10.12806/V8/I2/AB4

Introduction