Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 2 Chapter 3: What is Empirical Literature & Where can it be Found?

In Module 1, you read about the problem of pseudoscience. Here, we revisit the issue in addressing how to locate and assess scientific or empirical literature . In this chapter you will read about:

- distinguishing between what IS and IS NOT empirical literature

- how and where to locate empirical literature for understanding diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Probably the most important take-home lesson from this chapter is that one source is not sufficient to being well-informed on a topic. It is important to locate multiple sources of information and to critically appraise the points of convergence and divergence in the information acquired from different sources. This is especially true in emerging and poorly understood topics, as well as in answering complex questions.

What Is Empirical Literature

Social workers often need to locate valid, reliable information concerning the dimensions of a population group or subgroup, a social work problem, or social phenomenon. They might also seek information about the way specific problems or resources are distributed among the populations encountered in professional practice. Or, social workers might be interested in finding out about the way that certain people experience an event or phenomenon. Empirical literature resources may provide answers to many of these types of social work questions. In addition, resources containing data regarding social indicators may also prove helpful. Social indicators are the “facts and figures” statistics that describe the social, economic, and psychological factors that have an impact on the well-being of a community or other population group.The United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) are examples of organizations that monitor social indicators at a global level: dimensions of population trends (size, composition, growth/loss), health status (physical, mental, behavioral, life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality, fertility/child-bearing, and diseases like HIV/AIDS), housing and quality of sanitation (water supply, waste disposal), education and literacy, and work/income/unemployment/economics, for example.

Three characteristics stand out in empirical literature compared to other types of information available on a topic of interest: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/replicability/reproducibility. Let’s look a little more closely at these three features.

Systematic Observation and Methodology. The hallmark of empiricism is “repeated or reinforced observation of the facts or phenomena” (Holosko, 2006, p. 6). In empirical literature, established research methodologies and procedures are systematically applied to answer the questions of interest.

Objectivity. Gathering “facts,” whatever they may be, drives the search for empirical evidence (Holosko, 2006). Authors of empirical literature are expected to report the facts as observed, whether or not these facts support the investigators’ original hypotheses. Research integrity demands that the information be provided in an objective manner, reducing sources of investigator bias to the greatest possible extent.

Transparency and Replicability/Reproducibility. Empirical literature is reported in such a manner that other investigators understand precisely what was done and what was found in a particular research study—to the extent that they could replicate the study to determine whether the findings are reproduced when repeated. The outcomes of an original and replication study may differ, but a reader could easily interpret the methods and procedures leading to each study’s findings.

What is NOT Empirical Literature

By now, it is probably obvious to you that literature based on “evidence” that is not developed in a systematic, objective, transparent manner is not empirical literature. On one hand, non-empirical types of professional literature may have great significance to social workers. For example, social work scholars may produce articles that are clearly identified as describing a new intervention or program without evaluative evidence, critiquing a policy or practice, or offering a tentative, untested theory about a phenomenon. These resources are useful in educating ourselves about possible issues or concerns. But, even if they are informed by evidence, they are not empirical literature. Here is a list of several sources of information that do not meet the standard of being called empirical literature:

- your course instructor’s lectures

- political statements

- advertisements

- newspapers & magazines (journalism)

- television news reports & analyses (journalism)

- many websites, Facebook postings, Twitter tweets, and blog postings

- the introductory literature review in an empirical article

You may be surprised to see the last two included in this list. Like the other sources of information listed, these sources also might lead you to look for evidence. But, they are not themselves sources of evidence. They may summarize existing evidence, but in the process of summarizing (like your instructor’s lectures), information is transformed, modified, reduced, condensed, and otherwise manipulated in such a manner that you may not see the entire, objective story. These are called secondary sources, as opposed to the original, primary source of evidence. In relying solely on secondary sources, you sacrifice your own critical appraisal and thinking about the original work—you are “buying” someone else’s interpretation and opinion about the original work, rather than developing your own interpretation and opinion. What if they got it wrong? How would you know if you did not examine the primary source for yourself? Consider the following as an example of “getting it wrong” being perpetuated.

Example: Bullying and School Shootings . One result of the heavily publicized April 1999 school shooting incident at Columbine High School (Colorado), was a heavy emphasis placed on bullying as a causal factor in these incidents (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017), “creating a powerful master narrative about school shootings” (Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017, p. 3). Naturally, with an identified cause, a great deal of effort was devoted to anti-bullying campaigns and interventions for enhancing resilience among youth who experience bullying. However important these strategies might be for promoting positive mental health, preventing poor mental health, and possibly preventing suicide among school-aged children and youth, it is a mistaken belief that this can prevent school shootings (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017). Many times the accounts of the perpetrators having been bullied come from potentially inaccurate third-party accounts, rather than the perpetrators themselves; bullying was not involved in all instances of school shooting; a perpetrator’s perception of being bullied/persecuted are not necessarily accurate; many who experience severe bullying do not perpetrate these incidents; bullies are the least targeted shooting victims; perpetrators of the shooting incidents were often bullying others; and, bullying is only one of many important factors associated with perpetrating such an incident (Ioannou, Hammond, & Simpson, 2015; Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017; Newman &Fox, 2009; Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017). While mass media reports deliver bullying as a means of explaining the inexplicable, the reality is not so simple: “The connection between bullying and school shootings is elusive” (Langman, 2014), and “the relationship between bullying and school shooting is, at best, tenuous” (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017, p. 940). The point is, when a narrative becomes this publicly accepted, it is difficult to sort out truth and reality without going back to original sources of information and evidence.

What May or May Not Be Empirical Literature: Literature Reviews

Investigators typically engage in a review of existing literature as they develop their own research studies. The review informs them about where knowledge gaps exist, methods previously employed by other scholars, limitations of prior work, and previous scholars’ recommendations for directing future research. These reviews may appear as a published article, without new study data being reported (see Fields, Anderson, & Dabelko-Schoeny, 2014 for example). Or, the literature review may appear in the introduction to their own empirical study report. These literature reviews are not considered to be empirical evidence sources themselves, although they may be based on empirical evidence sources. One reason is that the authors of a literature review may or may not have engaged in a systematic search process, identifying a full, rich, multi-sided pool of evidence reports.

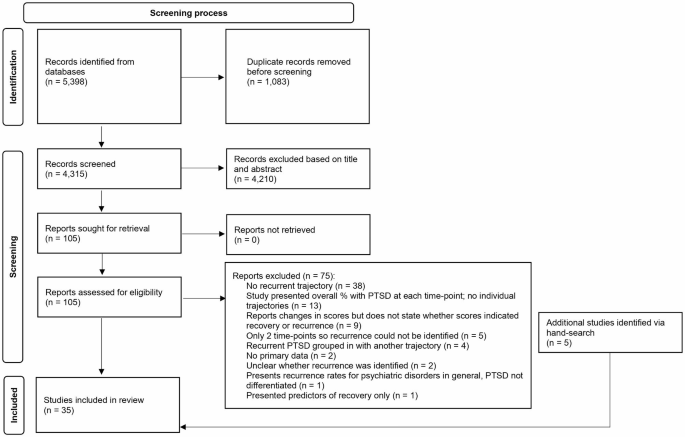

There is, however, a type of review that applies systematic methods and is, therefore, considered to be more strongly rooted in evidence: the systematic review .

Systematic review of literature. A systematic reviewis a type of literature report where established methods have been systematically applied, objectively, in locating and synthesizing a body of literature. The systematic review report is characterized by a great deal of transparency about the methods used and the decisions made in the review process, and are replicable. Thus, it meets the criteria for empirical literature: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/reproducibility. We will work a great deal more with systematic reviews in the second course, SWK 3402, since they are important tools for understanding interventions. They are somewhat less common, but not unheard of, in helping us understand diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Locating Empirical Evidence

Social workers have available a wide array of tools and resources for locating empirical evidence in the literature. These can be organized into four general categories.

Journal Articles. A number of professional journals publish articles where investigators report on the results of their empirical studies. However, it is important to know how to distinguish between empirical and non-empirical manuscripts in these journals. A key indicator, though not the only one, involves a peer review process . Many professional journals require that manuscripts undergo a process of peer review before they are accepted for publication. This means that the authors’ work is shared with scholars who provide feedback to the journal editor as to the quality of the submitted manuscript. The editor then makes a decision based on the reviewers’ feedback:

- Accept as is

- Accept with minor revisions

- Request that a revision be resubmitted (no assurance of acceptance)

When a “revise and resubmit” decision is made, the piece will go back through the review process to determine if it is now acceptable for publication and that all of the reviewers’ concerns have been adequately addressed. Editors may also reject a manuscript because it is a poor fit for the journal, based on its mission and audience, rather than sending it for review consideration.

Indicators of journal relevance. Various journals are not equally relevant to every type of question being asked of the literature. Journals may overlap to a great extent in terms of the topics they might cover; in other words, a topic might appear in multiple different journals, depending on how the topic was being addressed. For example, articles that might help answer a question about the relationship between community poverty and violence exposure might appear in several different journals, some with a focus on poverty, others with a focus on violence, and still others on community development or public health. Journal titles are sometimes a good starting point but may not give a broad enough picture of what they cover in their contents.

In focusing a literature search, it also helps to review a journal’s mission and target audience. For example, at least four different journals focus specifically on poverty:

- Journal of Children & Poverty

- Journal of Poverty

- Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

- Poverty & Public Policy

Let’s look at an example using the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice . Information about this journal is located on the journal’s webpage: http://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/journal-of-poverty-and-social-justice . In the section headed “About the Journal” you can see that it is an internationally focused research journal, and that it addresses social justice issues in addition to poverty alone. The research articles are peer-reviewed (there appear to be non-empirical discussions published, as well). These descriptions about a journal are almost always available, sometimes listed as “scope” or “mission.” These descriptions also indicate the sponsorship of the journal—sponsorship may be institutional (a particular university or agency, such as Smith College Studies in Social Work ), a professional organization, such as the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) or the National Association of Social Work (NASW), or a publishing company (e.g., Taylor & Frances, Wiley, or Sage).

Indicators of journal caliber. Despite engaging in a peer review process, not all journals are equally rigorous. Some journals have very high rejection rates, meaning that many submitted manuscripts are rejected; others have fairly high acceptance rates, meaning that relatively few manuscripts are rejected. This is not necessarily the best indicator of quality, however, since newer journals may not be sufficiently familiar to authors with high quality manuscripts and some journals are very specific in terms of what they publish. Another index that is sometimes used is the journal’s impact factor . Impact factor is a quantitative number indicative of how often articles published in the journal are cited in the reference list of other journal articles—the statistic is calculated as the number of times on average each article published in a particular year were cited divided by the number of articles published (the number that could be cited). For example, the impact factor for the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice in our list above was 0.70 in 2017, and for the Journal of Poverty was 0.30. These are relatively low figures compared to a journal like the New England Journal of Medicine with an impact factor of 59.56! This means that articles published in that journal were, on average, cited more than 59 times in the next year or two.

Impact factors are not necessarily the best indicator of caliber, however, since many strong journals are geared toward practitioners rather than scholars, so they are less likely to be cited by other scholars but may have a large impact on a large readership. This may be the case for a journal like the one titled Social Work, the official journal of the National Association of Social Workers. It is distributed free to all members: over 120,000 practitioners, educators, and students of social work world-wide. The journal has a recent impact factor of.790. The journals with social work relevant content have impact factors in the range of 1.0 to 3.0 according to Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), particularly when they are interdisciplinary journals (for example, Child Development , Journal of Marriage and Family , Child Abuse and Neglect , Child Maltreatmen t, Social Service Review , and British Journal of Social Work ). Once upon a time, a reader could locate different indexes comparing the “quality” of social work-related journals. However, the concept of “quality” is difficult to systematically define. These indexes have mostly been replaced by impact ratings, which are not necessarily the best, most robust indicators on which to rely in assessing journal quality. For example, new journals addressing cutting edge topics have not been around long enough to have been evaluated using this particular tool, and it takes a few years for articles to begin to be cited in other, later publications.

Beware of pseudo-, illegitimate, misleading, deceptive, and suspicious journals . Another side effect of living in the Age of Information is that almost anyone can circulate almost anything and call it whatever they wish. This goes for “journal” publications, as well. With the advent of open-access publishing in recent years (electronic resources available without subscription), we have seen an explosion of what are called predatory or junk journals . These are publications calling themselves journals, often with titles very similar to legitimate publications and often with fake editorial boards. These “publications” lack the integrity of legitimate journals. This caution is reminiscent of the discussions earlier in the course about pseudoscience and “snake oil” sales. The predatory nature of many apparent information dissemination outlets has to do with how scientists and scholars may be fooled into submitting their work, often paying to have their work peer-reviewed and published. There exists a “thriving black-market economy of publishing scams,” and at least two “journal blacklists” exist to help identify and avoid these scam journals (Anderson, 2017).

This issue is important to information consumers, because it creates a challenge in terms of identifying legitimate sources and publications. The challenge is particularly important to address when information from on-line, open-access journals is being considered. Open-access is not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate scientists may pay sizeable fees to legitimate publishers to make their work freely available and accessible as open-access resources. On-line access is also not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate publishers often make articles available on-line to provide timely access to the content, especially when publishing the article in hard copy will be delayed by months or even a year or more. On the other hand, stating that a journal engages in a peer-review process is no guarantee of quality—this claim may or may not be truthful. Pseudo- and junk journals may engage in some quality control practices, but may lack attention to important quality control processes, such as managing conflict of interest, reviewing content for objectivity or quality of the research conducted, or otherwise failing to adhere to industry standards (Laine & Winker, 2017).

One resource designed to assist with the process of deciphering legitimacy is the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). The DOAJ is not a comprehensive listing of all possible legitimate open-access journals, and does not guarantee quality, but it does help identify legitimate sources of information that are openly accessible and meet basic legitimacy criteria. It also is about open-access journals, not the many journals published in hard copy.

An additional caution: Search for article corrections. Despite all of the careful manuscript review and editing, sometimes an error appears in a published article. Most journals have a practice of publishing corrections in future issues. When you locate an article, it is helpful to also search for updates. Here is an example where data presented in an article’s original tables were erroneous, and a correction appeared in a later issue.

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 12(8): e0181722. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5558917/

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2018).Correction—A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 13(3): e0193937. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193937

Search Tools. In this age of information, it is all too easy to find items—the problem lies in sifting, sorting, and managing the vast numbers of items that can be found. For example, a simple Google® search for the topic “community poverty and violence” resulted in about 15,600,000 results! As a means of simplifying the process of searching for journal articles on a specific topic, a variety of helpful tools have emerged. One type of search tool has previously applied a filtering process for you: abstracting and indexing databases . These resources provide the user with the results of a search to which records have already passed through one or more filters. For example, PsycINFO is managed by the American Psychological Association and is devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science. It contains almost 4.5 million records and is growing every month. However, it may not be available to users who are not affiliated with a university library. Conducting a basic search for our topic of “community poverty and violence” in PsychINFO returned 1,119 articles. Still a large number, but far more manageable. Additional filters can be applied, such as limiting the range in publication dates, selecting only peer reviewed items, limiting the language of the published piece (English only, for example), and specified types of documents (either chapters, dissertations, or journal articles only, for example). Adding the filters for English, peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2010 and 2017 resulted in 346 documents being identified.

Just as was the case with journals, not all abstracting and indexing databases are equivalent. There may be overlap between them, but none is guaranteed to identify all relevant pieces of literature. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the questions asked of the literature:

- Academic Search Complete—multidisciplinary index of 9,300 peer-reviewed journals

- AgeLine—multidisciplinary index of aging-related content for over 600 journals

- Campbell Collaboration—systematic reviews in education, crime and justice, social welfare, international development

- Google Scholar—broad search tool for scholarly literature across many disciplines

- MEDLINE/ PubMed—National Library of medicine, access to over 15 million citations

- Oxford Bibliographies—annotated bibliographies, each is discipline specific (e.g., psychology, childhood studies, criminology, social work, sociology)

- PsycINFO/PsycLIT—international literature on material relevant to psychology and related disciplines

- SocINDEX—publications in sociology

- Social Sciences Abstracts—multiple disciplines

- Social Work Abstracts—many areas of social work are covered

- Web of Science—a “meta” search tool that searches other search tools, multiple disciplines

Placing our search for information about “community violence and poverty” into the Social Work Abstracts tool with no additional filters resulted in a manageable 54-item list. Finally, abstracting and indexing databases are another way to determine journal legitimacy: if a journal is indexed in a one of these systems, it is likely a legitimate journal. However, the converse is not necessarily true: if a journal is not indexed does not mean it is an illegitimate or pseudo-journal.

Government Sources. A great deal of information is gathered, analyzed, and disseminated by various governmental branches at the international, national, state, regional, county, and city level. Searching websites that end in.gov is one way to identify this type of information, often presented in articles, news briefs, and statistical reports. These government sources gather information in two ways: they fund external investigations through grants and contracts and they conduct research internally, through their own investigators. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the topic for which information is sought:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) at https://www.ahrq.gov/

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) at https://www.bjs.gov/

- Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of the CDC (MMWR-CDC) at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index.html

- Child Welfare Information Gateway at https://www.childwelfare.gov

- Children’s Bureau/Administration for Children & Families at https://www.acf.hhs.gov

- Forum on Child and Family Statistics at https://www.childstats.gov

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) at https://www.nih.gov , including (not limited to):

- National Institute on Aging (NIA at https://www.nia.nih.gov

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at https://www.nichd.nih.gov

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at https://www.nida.nih.gov

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at https://www.niehs.nih.gov

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at https://www.nimh.nih.gov

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at https://www.nimhd.nih.gov

- National Institute of Justice (NIJ) at https://www.nij.gov

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at https://www.samhsa.gov/

- United States Agency for International Development at https://usaid.gov

Each state and many counties or cities have similar data sources and analysis reports available, such as Ohio Department of Health at https://www.odh.ohio.gov/healthstats/dataandstats.aspx and Franklin County at https://statisticalatlas.com/county/Ohio/Franklin-County/Overview . Data are available from international/global resources (e.g., United Nations and World Health Organization), as well.

Other Sources. The Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies—previously the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—is a nonprofit institution that aims to provide government and private sector policy and other decision makers with objective analysis and advice for making informed health decisions. For example, in 2018 they produced reports on topics in substance use and mental health concerning the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease, the legal implications of emerging neurotechnologies, and a global agenda concerning the identification and prevention of violence (see http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/Topics/Substance-Abuse-Mental-Health.aspx ). The exciting aspect of this resource is that it addresses many topics that are current concerns because they are hoping to help inform emerging policy. The caution to consider with this resource is the evidence is often still emerging, as well.

Numerous “think tank” organizations exist, each with a specific mission. For example, the Rand Corporation is a nonprofit organization offering research and analysis to address global issues since 1948. The institution’s mission is to help improve policy and decision making “to help individuals, families, and communities throughout the world be safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous,” addressing issues of energy, education, health care, justice, the environment, international affairs, and national security (https://www.rand.org/about/history.html). And, for example, the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation is a philanthropic organization supporting research and research dissemination concerning health issues facing the United States. The foundation works to build a culture of health across systems of care (not only medical care) and communities (https://www.rwjf.org).

While many of these have a great deal of helpful evidence to share, they also may have a strong political bias. Objectivity is often lacking in what information these organizations provide: they provide evidence to support certain points of view. That is their purpose—to provide ideas on specific problems, many of which have a political component. Think tanks “are constantly researching solutions to a variety of the world’s problems, and arguing, advocating, and lobbying for policy changes at local, state, and federal levels” (quoted from https://thebestschools.org/features/most-influential-think-tanks/ ). Helpful information about what this one source identified as the 50 most influential U.S. think tanks includes identifying each think tank’s political orientation. For example, The Heritage Foundation is identified as conservative, whereas Human Rights Watch is identified as liberal.

While not the same as think tanks, many mission-driven organizations also sponsor or report on research, as well. For example, the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) in the United States is a registered nonprofit organization. Its mission, along with other partnering organizations, private-sector groups, and federal agencies, is to promote policy and program development in research, prevention and treatment to provide information to, for, and about children of alcoholics (of all ages). Based on this mission, the organization supports knowledge development and information gathering on the topic and disseminates information that serves the needs of this population. While this is a worthwhile mission, there is no guarantee that the information meets the criteria for evidence with which we have been working. Evidence reported by think tank and mission-driven sources must be utilized with a great deal of caution and critical analysis!

In many instances an empirical report has not appeared in the published literature, but in the form of a technical or final report to the agency or program providing the funding for the research that was conducted. One such example is presented by a team of investigators funded by the National Institute of Justice to evaluate a program for training professionals to collect strong forensic evidence in instances of sexual assault (Patterson, Resko, Pierce-Weeks, & Campbell, 2014): https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/247081.pdf . Investigators may serve in the capacity of consultant to agencies, programs, or institutions, and provide empirical evidence to inform activities and planning. One such example is presented by Maguire-Jack (2014) as a report to a state’s child maltreatment prevention board: https://preventionboard.wi.gov/Documents/InvestmentInPreventionPrograming_Final.pdf .

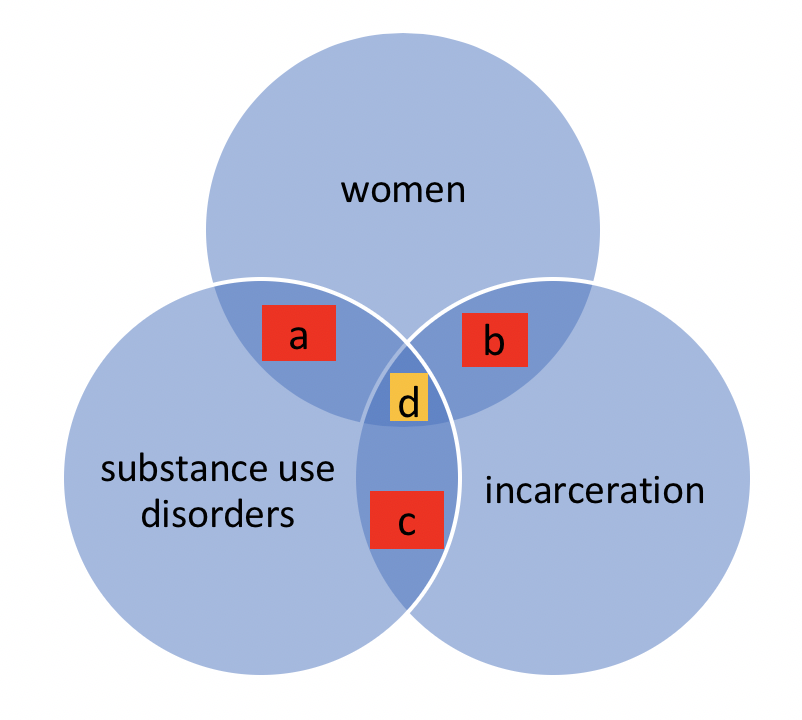

When Direct Answers to Questions Cannot Be Found. Sometimes social workers are interested in finding answers to complex questions or questions related to an emerging, not-yet-understood topic. This does not mean giving up on empirical literature. Instead, it requires a bit of creativity in approaching the literature. A Venn diagram might help explain this process. Consider a scenario where a social worker wishes to locate literature to answer a question concerning issues of intersectionality. Intersectionality is a social justice term applied to situations where multiple categorizations or classifications come together to create overlapping, interconnected, or multiplied disadvantage. For example, women with a substance use disorder and who have been incarcerated face a triple threat in terms of successful treatment for a substance use disorder: intersectionality exists between being a woman, having a substance use disorder, and having been in jail or prison. After searching the literature, little or no empirical evidence might have been located on this specific triple-threat topic. Instead, the social worker will need to seek literature on each of the threats individually, and possibly will find literature on pairs of topics (see Figure 3-1). There exists some literature about women’s outcomes for treatment of a substance use disorder (a), some literature about women during and following incarceration (b), and some literature about substance use disorders and incarceration (c). Despite not having a direct line on the center of the intersecting spheres of literature (d), the social worker can develop at least a partial picture based on the overlapping literatures.

Figure 3-1. Venn diagram of intersecting literature sets.

Take a moment to complete the following activity. For each statement about empirical literature, decide if it is true or false.

Social Work 3401 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- 66 Ogoja Road, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State 23480 NG.

- Sun - Fri 24Hours Saturday CLOSED

- support [@] writersking.com

- +23480-6075-5653 Hot Line

- Data Collection/Analysis

- Hire Proposal Writers

- Hire Essay Writers

- Hire Paper Writers

- Proofreading Services

- Thesis/Dissertation Writers

- Virtual Supervisor

- Turnitin Checker

- Book Chapter Writer

- Hire Business Writing Services

- Hire Blog Writers

- Writers King TV

- Proposal Sample

- Chapter 1-3 Sample

- Term Paper Sample

- Report Assignment Sample

- Course work Sample

- Payment Options

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service/Use

- Business Guide

- Academic Writing Guide

- General Writing Guide

- Research News

- Writing Paper Samples

- February 19, 2022

- Posted by: Chimnecherem Eke

- Category: Academic Writing Guide

Differences between Empirical Review and Literature Review

As a researcher, you might wonder about the difference between an Empirical Review and Literature Review. If you are going to write an essay or article, you must first figure out what your topic is. The subject determines the flow of the writing, the material provided, and every other element.

Content Outline

Get your seat closer; let’s get to what you need to know about Empirical Review and Literature Review and their notable differences.

Students often accost empirical studies and literature reviews while preparing a research paper . It’s critical to know the difference between the two in order to craft a solid piece of writing. Both articles are responsible for presenting the facts, but their strategies differ.

Students are often perplexed when asked what empirical research is. The following is an explanation of the differences between a systematic review and a literature review:

Definition of Empirical review -Empirical Review and Literature Review

An empirical literature review, also known as a systematic literature review, analyzes previous empirical studies in order to provide an answer to a specific research topic.

Rather than drawing information from theories or beliefs, empirical research relies on observations and measurements to arrive at conclusions. To address specific research inquiries, it could involve making a list of people, behaviours, or events that are being researched.

In some cases, reviews of studies that involve experiments are used in empirical reviews to generate findings based on experience that may be seen directly or indirectly. Most of the time, the analysis entails quantifying the data and drawing conclusions.

The goal is to provide data that can be quantified using established scientific methods . Research reviewers thoroughly examine all findings of other authors before drawing any conclusions in an essay or paper.

As a result of carefully planned and monitored observations, the experiment is carried out, and the resulting conclusion is rigorously monitored. In contrast to other types of literature reviews, the focus here is on the most recent results of the experimental studies as it is now being conducted. A hypothesis may also be a forecast of a previously presented theory based on prior material.

Empirical evidence refers to data gathered via testing or observation in this context. These data are collected and analyzed by scientists.

For example, an empirical review could involve reviewing the study of another researcher on a group of listeners exposed to upbeat music or a work on learning and improvisation that examines other studies on work that theorizes about the educational value of improvisational principles and practices, such as Viola Spolin and Keith Johnstone ‘s writings in which they present their beliefs, impressions, ideas, and theories about those.

Defining Literature Review -Empirical Review and Literature Review

The literature review , instead of an empirical review, necessitates reading several related studies. Other theoretical sources are used to compile the facts and information included in this piece. The accumulation of all literary works may lead to new deductions. Information and hypotheses, on the other hand, have already been developed.

To generate cohesive findings, a literature review compiles all necessary data. No new theories can be developed since no experimental work can be done.

There is an important function for the literature review in uncovering defining, and clarifying key ideas that will be utilized throughout the empirical parts of the paper argues.

A well-written review article may shed light on the current state of knowledge, explain apparent inconsistencies, pinpoint areas in need of more study, and even help to forge a consensus where none previously existed. A well-written review may also assist you in your professional life. Reviews aid in recognition and advancement due to their high citation frequency.

Selecting the type of review to conduct -Empirical Review and Literature Review

College students are often required to write several papers as part of their studies. When a student does a literature review, he or she attempts to use the written word to support or refute an idea or hypothesis. He or she may test a theory or try to find an answer to a specific issue based on already-known information.

An empirical review is a piece of writing based on a study that was done purely for the purpose of publishing it. Calibrated instruments are used to conduct the experiment in a scientifically controlled way.

In this age of AI, research has become more interesting as you can use AI for your research study to make reviewing literature easier (Thesis, Dissertation, Research paper, among others). AI tools like SciSpace literature review can help you compare, contrast, and analyze research papers more efficiently.

It would be best to start writing as soon as you finish the experiment. During the study, observations should be recorded methodically. This aids in developing coherence, which is more easily understood even in the future. Additionally, starting the writing process early allows for more time for revision and results in higher-quality work.

Because experiments may take some time to produce the desired results, this is especially important for empirical studies. Leaving the writing to the last minute and beginning it when the deadline is nearing will just add to the stress and complexity of the process. This interferes with the job and lowers the quality. As a result, staying on top of your job helps your paper and your personal life grow.

Almost every research article includes a review of the literature. An empirical study must first be established inside an accepted theory before they can publish their findings. In other words, before we get into our methodology and research questions, we’ll go through what’s been done previously and how the variables we want to investigate fit into the theories and frameworks of our research field.

An empirical literature review, also known as a systematic literature review, analyzes previous empirical studies in order to provide an answer to a specific research topic. Randomized controlled trials are the most common kind of empirical study.

Both of these tasks are similar in that they need to review previous work on the topic. The empirical literature review, on the other hand, seeks to address a particular empirical issue by analyzing data. The theoretical literature review serves primarily to place your research within a broader framework. A theoretical review will be included in systematic empirical reviews to help researchers understand why a specific research topic is worth investigating.

Thank you for your time, we hope you got value reading Differences between Empirical Review and Literature Review?

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an example of an empirical review.

An empirical review is an academic review that focuses on summarizing and analyzing the findings of empirical research studies. Empirical research involves collecting and analysing primary data through experiments, surveys, observations, or any other data collection method(s).

An example of an empirical review would be a critical examination of several recent scientific studies that have investigated the effectiveness of a specific drug in treating a particular medical condition. The empirical review would include the study objectives, a summary of the research methods, key findings, and a critical evaluation of the research design, data collection, and statistical analysis methods employed in those studies.

What is the purpose of a literature review in empirical research studies?

A literature review in empirical research studies provides a comprehensive and systematic overview of existing published research and scholarly works related to the topic under investigation. This serves several important purposes:

Contextualization : It helps researchers place their study within the context of existing knowledge and identify gaps or areas where further research is needed.

Identification of Theoretical Frameworks : A literature review aids in identifying relevant theories and concepts that can inform the research design and data analysis in empirical studies.

Methodological Guidance: It offers insights into prior studies’ methodologies and research methods, helping researchers make informed decisions about their own data collection and analysis techniques.

Hypothesis Development: It can assist in formulating research hypotheses and research questions based on the existing literature.

Validation of Research Question: By reviewing the literature, researchers can ensure that their research questions or hypotheses have not been adequately addressed in prior studies.

Identification of Variables: It helps identify key variables and factors examined in previous research, which can guide the selection of variables in the new study.

In summary, a literature review in empirical research serves as the foundation upon which a new empirical study is built, helping researchers gain a deep understanding of the existing knowledge in their field, refine their research questions, and make informed decisions about the research design and methods they will employ.

Some quotations on code mixing and code switching base on empirical review.

Drop your comment, question or suggestion for the post improvement Cancel reply

Find Us Today

Writers King LTD, Akachukwu Plaza,

66 Ogoja Road Abakaliki, Ebonyi State,

480101 Nigeria

Phone: 0806-075-5653

- Website: https://writersking.com/

- Email: support {@} writersking.com

- +2348060755653

Quick Links

Writing guide.

Penn State University Libraries

Empirical research in the social sciences and education.

- What is Empirical Research and How to Read It

- Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases

- Designing Empirical Research

- Ethics, Cultural Responsiveness, and Anti-Racism in Research

- Citing, Writing, and Presenting Your Work

Contact the Librarian at your campus for more help!

Introduction: What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools used in the present study

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

Reading and Evaluating Scholarly Materials

Reading research can be a challenge. However, the tutorials and videos below can help. They explain what scholarly articles look like, how to read them, and how to evaluate them:

- CRAAP Checklist A frequently-used checklist that helps you examine the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose of an information source.

- IF I APPLY A newer model of evaluating sources which encourages you to think about your own biases as a reader, as well as concerns about the item you are reading.

- Credo Video: How to Read Scholarly Materials (4 min.)

- Credo Tutorial: How to Read Scholarly Materials

- Credo Tutorial: Evaluating Information

- Credo Video: Evaluating Statistics (4 min.)

- Next: Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases >>

- Last Updated: Feb 18, 2024 8:33 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/emp

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Literature Reviews

Introduction, what is a literature review.

- Literature Reviews for Thesis or Dissertation

- Stand-alone and Systemic Reviews

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Texts on Conducting a Literature Review

- Identifying the Research Topic

- The Persuasive Argument

- Searching the Literature

- Creating a Synthesis

- Critiquing the Literature

- Building the Case for the Literature Review Document

- Presenting the Literature Review

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Higher Education Research

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Politics of Education

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Literature Reviews by Lawrence A. Machi , Brenda T. McEvoy LAST REVIEWED: 21 April 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 27 October 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0169

Literature reviews play a foundational role in the development and execution of a research project. They provide access to the academic conversation surrounding the topic of the proposed study. By engaging in this scholarly exercise, the researcher is able to learn and to share knowledge about the topic. The literature review acts as the springboard for new research, in that it lays out a logically argued case, founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about the topic. The case produced provides the justification for the research question or problem of a proposed study, and the methodological scheme best suited to conduct the research. It can also be a research project in itself, arguing policy or practice implementation, based on a comprehensive analysis of the research in a field. The term literature review can refer to the output or the product of a review. It can also refer to the process of Conducting a Literature Review . Novice researchers, when attempting their first research projects, tend to ask two questions: What is a Literature Review? How do you do one? While this annotated bibliography is neither definitive nor exhaustive in its treatment of the subject, it is designed to provide a beginning researcher, who is pursuing an academic degree, an entry point for answering the two previous questions. The article is divided into two parts. The first four sections of the article provide a general overview of the topic. They address definitions, types, purposes, and processes for doing a literature review. The second part presents the process and procedures for doing a literature review. Arranged in a sequential fashion, the remaining eight sections provide references addressing each step of the literature review process. References included in this article were selected based on their ability to assist the beginning researcher. Additionally, the authors attempted to include texts from various disciplines in social science to present various points of view on the subject.

Novice researchers often have a misguided perception of how to do a literature review and what the document should contain. Literature reviews are not narrative annotated bibliographies nor book reports (see Bruce 1994 ). Their form, function, and outcomes vary, due to how they depend on the research question, the standards and criteria of the academic discipline, and the orthodoxies of the research community charged with the research. The term literature review can refer to the process of doing a review as well as the product resulting from conducting a review. The product resulting from reviewing the literature is the concern of this section. Literature reviews for research studies at the master’s and doctoral levels have various definitions. Machi and McEvoy 2016 presents a general definition of a literature review. Lambert 2012 defines a literature review as a critical analysis of what is known about the study topic, the themes related to it, and the various perspectives expressed regarding the topic. Fink 2010 defines a literature review as a systematic review of existing body of data that identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes for explicit presentation. Jesson, et al. 2011 defines the literature review as a critical description and appraisal of a topic. Hart 1998 sees the literature review as producing two products: the presentation of information, ideas, data, and evidence to express viewpoints on the nature of the topic, as well as how it is to be investigated. When considering literature reviews beyond the novice level, Ridley 2012 defines and differentiates the systematic review from literature reviews associated with primary research conducted in academic degree programs of study, including stand-alone literature reviews. Cooper 1998 states the product of literature review is dependent on the research study’s goal and focus, and defines synthesis reviews as literature reviews that seek to summarize and draw conclusions from past empirical research to determine what issues have yet to be resolved. Theoretical reviews compare and contrast the predictive ability of theories that explain the phenomenon, arguing which theory holds the most validity in describing the nature of that phenomenon. Grant and Booth 2009 identified fourteen types of reviews used in both degree granting and advanced research projects, describing their attributes and methodologies.

Bruce, Christine Susan. 1994. Research students’ early experiences of the dissertation literature review. Studies in Higher Education 19.2: 217–229.

DOI: 10.1080/03075079412331382057

A phenomenological analysis was conducted with forty-one neophyte research scholars. The responses to the questions, “What do you mean when you use the words literature review?” and “What is the meaning of a literature review for your research?” identified six concepts. The results conclude that doing a literature review is a problem area for students.

Cooper, Harris. 1998. Synthesizing research . Vol. 2. 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

The introductory chapter of this text provides a cogent explanation of Cooper’s understanding of literature reviews. Chapter 4 presents a comprehensive discussion of the synthesis review. Chapter 5 discusses meta-analysis and depth.

Fink, Arlene. 2010. Conducting research literature reviews: From the Internet to paper . 3d ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

The first chapter of this text (pp. 1–16) provides a short but clear discussion of what a literature review is in reference to its application to a broad range of social sciences disciplines and their related professions.

Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 26.2: 91–108. Print.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

This article reports a scoping review that was conducted using the “Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis” (SALSA) framework. Fourteen literature review types and associated methodology make up the resulting typology. Each type is described by its key characteristics and analyzed for its strengths and weaknesses.

Hart, Chris. 1998. Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination . London: SAGE.

Chapter 1 of this text explains Hart’s definition of a literature review. Additionally, it describes the roles of the literature review, the skills of a literature reviewer, and the research context for a literature review. Of note is Hart’s discussion of the literature review requirements for master’s degree and doctoral degree work.

Jesson, Jill, Lydia Matheson, and Fiona M. Lacey. 2011. Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques . Los Angeles: SAGE.

Chapter 1: “Preliminaries” provides definitions of traditional and systematic reviews. It discusses the differences between them. Chapter 5 is dedicated to explaining the traditional review, while Chapter 7 explains the systematic review. Chapter 8 provides a detailed description of meta-analysis.

Lambert, Mike. 2012. A beginner’s guide to doing your education research project . Los Angeles: SAGE.

Chapter 6 (pp. 79–100) presents a thumbnail sketch for doing a literature review.

Machi, Lawrence A., and Brenda T. McEvoy. 2016. The literature review: Six steps to success . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

The introduction of this text differentiates between a simple and an advanced review and concisely defines a literature review.

Ridley, Diana. 2012. The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students . 2d ed. Sage Study Skills. London: SAGE.

In the introductory chapter, Ridley reviews many definitions of the literature review, literature reviews at the master’s and doctoral level, and placement of literature reviews within the thesis or dissertation document. She also defines and differentiates literature reviews produced for degree-affiliated research from the more advanced systematic review projects.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development