The Monster Study (Summary, Results, and Ethical Issues)

Psychologists and scientists often go into their line of work for the betterment of mankind. Through their experiments and tireless work, they hope to discover information that will cure diseases, uncover the root of certain disorders, and improve the general health of the population. That being said, it has not always been approached in the best way. Experiments on humans, especially those in marginalized groups, often cross ethical lines. One of the most well-known, line-crossing experiments is The Monster Study.

The experiment is not called the Monster Study because it involves any monsters - but it did threaten to ruin the reputation of the psychologists behind it. The idea was so scary to fellow the psychologist’s peers that the results were hidden away for years.

What Is The Monster Study?

The Monster Study was conducted by Dr. Wendell Johnson (a speech pathologist) to learn more about why children developed a stutter. Johnson developed the Monster Study to see if stuttering was a result of learned behavior or Biology, however, there are many ethical problems with the study.

When Was the Monster Study Conducted?

Dr. Johnson conducted the Monster Study back in 1936 at the University of Iowa. Ethics were not prioritized as they are now in psychology and scientific experiments. If this experiment had been proposed today, the researcher may have been stopped before they could begin!

What Happened in the Monster Study?

Johnson chose 22 orphans as participants for The Monster Study. Some of the orphans had a stutter. (It’s not uncommon for young children to have a stutter and then naturally “get over” the stutter without treatment.) Some of the orphans didn’t have a stutter.

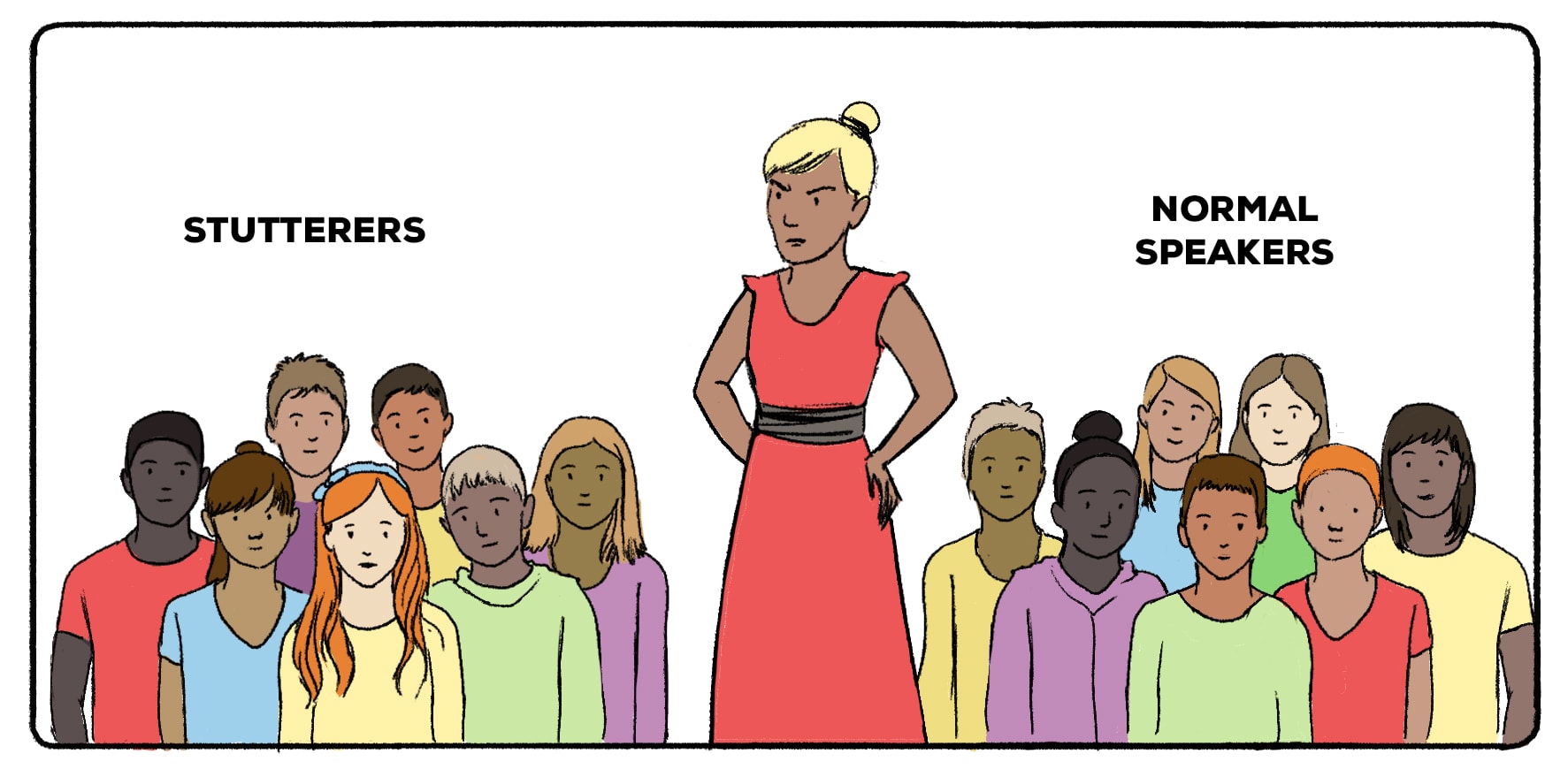

The orphans were split up into two groups, with stutterers and non-stutterers in both groups. One of these groups were labeled “normal speakers.” The others were labeled “stutterers.” Throughout the course of the experiment, the children were treated as such.

Johnson’s team met with the children every few weeks for five months to “evaluate” their speech. Children in the “normal” group were praised for their ability to speak well, even if they were actually stuttering or had problems speaking. Children in the “stuttering” group were told that they spoke poorly. They were told things like, “You must try to stop yourself immediately. Don't ever speak unless you can do it right.”

So what happened?

Results of The Monster Study

The children who were labeled “normal” weren’t affected much by the researchers’ praise. They saw improvement in only one child.

Children in the “stuttering” group fared a lot worse. Remember, not all of these children actually had a stutter - they were just told that they had a stutter. Of the six children that were falsely chastised for their speech, five developed speech problems. Reports show that these children became withdrawn and some stopped speaking altogether. These children were as young as five years old.

The study was created with good intentions. Johnson and his colleagues at the University of Iowa frequently conducted studies on themselves and willing adult subjects in the name of finding a cure for stuttering. But other colleagues worried that the use of orphans was crossing lines. Johnson wasn’t the only person conducting studies on marginalized groups in the name of science - Nazis were doing the same thing over in Germany. So the results of the study were never published.

The Impact of the Monster Study

Even in the 1930s, the Monster Study was crossing lines. Using orphans as test subjects is one thing - using minors in a study without their consent is another. Even the staff at the orphanage were unaware of what was really going on. This left many of the “stutterers” with unresolved psychological trauma. Researchers knew that this was a possibility. One member of Johnson’s team wrote “'I believe that in time they...will recover, but we certainly made a definite impression on them.”

She was right. The students’ schoolwork suffered and one ran away from the orphanage two years later. Later, she said that the study ruined her life.

Subjects didn’t know that they were a part of a study until sixty years after it happened. Only a handful of speech pathology students at the University of Iowa learned about the study after it was published. The information was useful - no one at the time had collected so much data about stuttering and how it developed. But the premise of the study was so horrifying that they nicknamed it “The Monster Study.”

The Monster Study didn’t become nationally infamous until 2001. The San Jose Mercury News published a series of articles about the study and commentary from speech pathologists. While some argued that the experiment crossed many ethical boundaries, others argued that it was just a result of its time. Some acknowledged the importance of the data, while others said that it didn’t come to any real conclusions.

At that point, Wendell Johnson had been dead for over 30 years. The University of Iowa issued a formal apology for the study. As all of this made national news, subjects started to learn the truth about what had happened to them.

The Lawsuit

The subjects sought justice. In the early 2000s, three of the subjects in the “stutterer” group sued the University of Iowa for emotional distress and fraudulent misrepresentation. The estates of three of the other “stutterers” were also included in the lawsuit. The plaintiffs claimed that the impact of the study had a lasting impact. One still “hates to talk.” Another, who says she now has a good life, said that she didn’t have many friends in the orphanage partly because she was so quiet.

They won their settlement and the University of Iowa paid over $1 million to the victims and their estates.

Importance and Infamy of The Monster Study

This study should never be repeated, but it shouldn’t be swept under the rug, either. The Monster Study is an important lesson about transparency and consent in experiments. If we don’t learn from these mistakes, we are bound to repeat them. Even 60 years later, it’s important to talk about The Monster Study, why it was wrong, and how psychology has evolved into a more ethical science.

Other Infamous Experiments in Social Psychology

The Monster Study is not the only controversial experiment in social psychology. It often ends up on lists besides experiments like the Stanford Prison Experiment and the Milgram Experiment.

The Stanford Prison Experiment

In the 1970s, psychologist Philip Zimbardo recruited a group of young men to pose as guards and prisoners. The guards received no formal training - just instructions to guard the prisoners. Although The Stanford Prison Experiment was meant to take place over the course of two weeks, it was cut short. The results were chilling, and have since been disputed.

Why did it get shut down? Allegedly, the guards took the role so seriously that they began to act cruelly toward the prisoners. Zimbardo asked the guards not to resort to physical violence, but they did. By the sixth day of the experiment, the prisoners had threatened to overthrow the guards. One prisoner stopped eating. Another had a breakdown. Yet, it took six days to call the whole experiment off.

The Milgram Experiment

Participants in the Milgram Experiment were faced with a choice: to shock (or not to shock) another participant. No electric shocks were actually administered, but the participants believed they would be. Researchers pressured the participants to administer the shock, despite the knowledge that the shocks were harmful or even deadly. Stanley Milgram put the experiment together to see how far people would go to obey the order of another.

Robbers Cave Experiment

This experiment was similar to the Stanford Prison Experiment, but with slightly younger participants. The Robbers Cave Experiment brought together two groups of boys at a summer camp. Researchers separated the two groups, assigned them names, and began to create conflict between them. Results were not as dramatic as the Stanford Prison Experiment, but similar criticisms have arisen. Also, like the Stanford Prison Experiment, the study only used young, white boys in the experiment, but made wide generalizations about social psychology. Excluding such a large portion of the population may be okay if you’re doing a study on one demographic, but this should be mentioned in the research.

What do all of these experiments have in common? They all have the potential to cause great trauma. The events of the experiments may not be “real” to researchers, but they are “real” to participants. The participants in the Milgram experiment truly believed they were administering deadly shocks. Prisoners in the Stanford Prison Experiment were physically harmed. Those effects don’t “go away” when the experiment is over. And usually, a participant may not understand the premise of an experiment before they sign up. This is why ethical codes in psychology are especially important, both for the participants in research and for anyone who views the conclusions derived from the research.

How to Conduct Ethical Experiments in Psychology

Ethics is more important nowadays than it was in the 1930s. But how do psychologists ensure that their experiments are ethically sound? Organizations like the American Psychological Association put together guidelines for psychologists and researchers to follow. Guidelines from the APA have been in place since the 50s, but they are constantly evolving.

Principle A: Beneficence and Non-maleficence

This principle goes beyond being nice. The APA encourages professionals to care for the people who are subjects in their research. Eliminating biases and prejudices is just one way that psychologists can act with beneficence and non-maleficence. (It’s important to note that subjects include humans and animals.)

Principle B: Fidelity and Responsibility

Psychologists have a responsibility not only to consider the well-being of their subjects, but to ensure that colleagues are acting ethically, too. The psychologists working alongside Philip Zimbardo or Stanley Milgram also had a responsibility to inform their colleagues of the possible effects of their controversial experiments.

Principle C: Integrity

Psychology research is supposed to reveal the truth about the way the mind works. Professionals may have an idea about how the study will turn out, but they must keep an open mind. If the results don’t match the psychologist’s hypothesis, they have to report that honestly. Skewing the results, or skewing the study in order to get certain results, is not ethical.

There is controversy as to whether Philip Zimbardo, for example, skewed the Stanford Prison Experiment to make the guards more cruel to prisoners and the results more dramatic. But to find the expose that challenges his findings is harder than learning about the Stanford Prison Experiment itself!

Principle D: Justice

Treating everyone equally is crucial to keeping psychology a just field. Patients should be held in the same esteem regardless of their background, age, education level, etc. They should also have access to important information in psychology that might benefit their lives and the lives of others.

Principle E: Respect for People's Rights and Dignity

Finally, psychologists must show respect for the rights and dignity of all people. Maintaining confidentiality is one way to achieve this goal. Why? Think about the Milgram experiment. How would you feel knowing that, under the pressure of the experiment, you hit the “shock” button? People might tell you that you’re cruel. You might feel guilty already, and your guilt may be amplified if your identity were to get out. Confidentiality is key to dignity.

Related posts:

- Stanley Milgram (Psychologist Biography)

- Philip Zimbardo (Biography + Experiments)

- Stanford Prison Experiment

- The Little Albert Experiment

- Human Experimentation List (in Psychology)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Introduction: Case Studies in the Ethics of Mental Health Research

Joseph millum.

Clinical Center Department of Bioethics/Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

This collection presents six case studies on the ethics of mental health research, written by scientific researchers and ethicists from around the world. We publish them here as a resource for teachers of research ethics and as a contribution to several ongoing ethical debates. Each consists of a description of a research study that was proposed or carried out and an in-depth analysis of the ethics of the study.

Building Global Capacity in Mental Health Research

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are more than 450 million people with mental, neurological, or behavioral problems worldwide ( WHO, 2005a ). Mental health problems are estimated to account for 13% of the global burden of disease, principally from unipolar and bipolar depression, alcohol and substance-use disorders, schizophrenia, and dementia. Nevertheless, in many countries, mental health is accorded a low priority; for example, a 2005 WHO analysis found that nearly a third of low-income countries who reported a mental health budget spent less than 1% of their total health budget on mental health ( WHO, 2005b ).

Despite the high burden of disease and some partially effective treatments that can be implemented in countries with weaker healthcare delivery systems ( Hyman et al., 2006 ), there exist substantial gaps in our knowledge of how to treat most mental health conditions. A 2007 Lancet Series entitled Global Mental Health claimed that the “rudimentary level of mental health-service research programmes in many nations also contributes to poor delivery of mental health care” ( Jacob et al., 2007 ). Its recommendations for mental health research priorities included research into the effects of interactions between mental health and other health conditions ( Prince et al., 2007 ), interventions for childhood developmental disabilities ( Patel et al., 2007 ), cost-effectiveness analysis, the scaling up of effective interventions, and the development of interventions that can be delivered by nonspecialist health workers ( Lancet Global Mental Health Group, 2007 ). All of these priorities require research in environments where the prevailing health problems and healthcare services match those of the populations the research will benefit, which suggests that research must take place all around the world. Similarly, many of the priorities identified by the Grand Challenges in Mental Health Initiative require focus on local environments, cultural factors, and the health systems of low- and middle-income countries. All the challenges “emphasize the need for global cooperation in the conduct of research” ( Collins et al., 2011 ).

Notwithstanding the need for research that is sensitive to different social and economic contexts, the trend of outsourcing to medical research to developing countries shows no sign of abating ( Thiers et al., 2008 ). Consequently, a substantial amount of mental health research will, in any case, take place in low- and middle-income countries, as well as rich countries, during the next few years.

The need for local research and the continuing increase in the international outsourcing of research imply that there is a pressing need to build the capacity to conduct good quality mental health research around the world. However, the expansion of worldwide capacity to conduct mental health research requires more than simply addressing low levels of funding for researchers and the imbalance between the resources available in rich and poor countries. People with mental health disorders are often thought to be particularly vulnerable subjects. This may be a product of problems related to their condition, such as where the condition reduces the capacity to make autonomous decisions. It may also result from social conditions because people with mental disorders are disproportionately likely to be poor, are frequently stigmatized as a result of their condition, and may be victims of human rights abuses ( Weiss et al., 2001 ; WHO, 2005a ). As a result, it is vitally important that the institutional resources and expertise are in place for ensuring that this research is carried out ethically.

Discussion at a special session at the 7th Global Forum on Bioethics in Research revealed the perception that many mental health researchers are not very interested in ethics and showed up a lack of ethics resources directly related to their work. This collection of case studies in the ethics of mental health research responds to that gap.

This collection comprises six case studies written by contributors from around the world ( Table 1 ). Each describes a mental health research study that raised difficult ethical issues, provides background and analysis of those issues, and draws conclusions about the ethics of the study, including whether it was ethical as it stood and how it ought to be amended otherwise. Three of the case studies are written by scientists who took part in the research they analyzed. For these cases, we have asked scholars independent of the research to write short commentaries on them. It is valuable to hear how the researchers themselves grapple with the ethical issues they encounter, as well as to hear the views of people with more distance from the research enterprise. Some of the ethical issues raised here have not been discussed before in the bioethics literature; others are more common concerns that have not received much attention in the context of international research. The case studies are intended to both expand academic discussion of some of the key questions related to research into mental health and for use in teaching ethics.

Case studies are an established teaching tool. Ethical analyses of such cases demonstrate the relevance of ethics to the actual practice of medical research and provide paradigmatic illustrations of the application of ethical principles to particular research situations. Concrete cases help generate and guide discussion and assist students who have trouble dealing with ethical concepts in abstraction. Through structured discussion, ethical development and decision-making skills can be enhanced. Moreover, outside of the teaching context, case study analyses provide a means to generate and focus debate on the relevant ethical issues, which can both highlight their importance and help academic discussion to advance.

People working in mental health research can benefit most from case studies that are specific to mental health. Even though, as outlined below, many of the same ethical problems arise in mental health research as elsewhere, the details of how they arise are important. For example, the nature of depression and the variation in effectiveness of antidepressive medication make a difference to how we should assess the ethics of placebo-controlled trials for new antidepressants. Moreover, seeing how familiar ethical principles are applied to one's own research specialty makes it easier to think about the ethics of one's own research. The cases in this collection highlight the commonalities and the variation in the ethical issues facing researchers in mental health around the world.

The current literature contains some other collections of ethics case studies that may be useful to mental health researchers. I note four important collections here, to which interested scholars may want to refer. Lavery et al.'s (2007) Ethical Issues in International Bio-medical Research provides in-depth analyses of ethically problematic research, mostly in low- and middle-income countries, although none of these cases involve mental health. Cash et al.'s (2009) Casebook on Ethical Issues in International Health Research also focuses on research in low- and middle-income countries, and several of the 64 short case descriptions focus on populations with mental health problems. Two further collections focus on mental health research, in particular. Dubois (2007) and colleagues developed short and longer US-based case studies for teaching as part of their “Ethics in Mental Health Research” training course. Finally, Hoagwood et al.'s (1996) book Ethical Issues in Mental Health Research with Children and Adolescents contains a casebook of 61 short case descriptions, including a few from outside the United States and Western Europe. For teachers and academics in search of more case studies, these existing collections should be very useful. Here, we expand on the available resources with six case studies from around the world with extended ethical analyses.

The remainder of this introduction provides an overview of some of the most important ethical issues that arise in mental health research and describes some of the more significant ethics guidance documents that apply.

Ethical Issues in Mental Health Research

The same principles can be applied in assessing the ethics of mental health research as to other research using human participants ( Emanuel et al., 2000 ). Concerns about the social value of research, risks, informed consent, and the fair treatment of participants all still apply. This means that we can learn from the work done in other areas of human subjects research. However, specific research contexts make a difference to how the more general ethical principles should be applied to them. Different medical conditions may require distinctive research designs, different patient populations may need special protections, and different locations may require researchers to respond to study populations who are very poor and lack access to health care or to significant variations in regulatory systems. The ethical analysis of international mental health research therefore needs to be tailored to its particularities.

Each case study in this collection focuses on the particular ethical issues that are relevant to the research it analyzes. Nevertheless, some issues arise in multiple cases. For example, questions about informed consent arise in the context of research with stroke patients, with students, and with other vulnerable groups. To help the reader compare the treatment of an ethical issue across the different case studies, the ethical analyses use the same nine headings to delineate the issues they consider. These are social value, study design, study population, informed consent, risks and benefits, confidentiality, post-trial obligations, legal versus ethical obligations, and oversight.

Here, I focus on five of these ethical issues as they arise in the context of international mental health research: (1) study design, (2) study population, (3) risks and benefits, (4) informed consent, and (5) post-trial obligations. I close by mentioning some of the most important guidelines that pertain to mental health research.

Study Design

The scientific design of a research study determines what sort of data it can generate. For example, the decision about what to give participants in each arm of a controlled trial determines what interventions the trial compares and what questions about relative safety and efficacy it can answer. What data a study generates makes a difference to the ethics of the study because research that puts human beings at risk is ethically justified in terms of the social value of the knowledge it produces. It is widely believed that human subject research without any social value is unethical and that the greater the research risks to participants, the greater the social value of the research must be to compensate ( Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences [CIOMS], 2002 ; World Medical Association, 2008 ). However, changing the scientific design of a study frequently changes what happens to research participants, too. For example, giving a control group in a treatment trial an existing effective treatment rather than placebo makes it more likely that their condition will improve but may expose them to adverse effects they would not otherwise experience. Therefore, questions of scientific design can be ethically very complex because different possible designs are compared both in terms of the useful knowledge they may generate and their potential impact on participants.

One of the more controversial questions of scientific design concerns the standard of care that is offered to participants in controlled trials. Some commentators argue that research that tests therapeutic interventions is only permissible if there is equipoise concerning the relative merits of the treatments being compared, that is, there are not good reasons to think that participants in any arm of the trial are receiving inferior treatment ( Joffe and Truog, 2008 ). If there is not equipoise, the argument goes, then physician-researchers will be breaching their duty to give their patients the best possible care ( Freedman, 1987 ).

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP) described in the case study by Charles Zeanah was a randomized controlled trial comparing foster care with institutional care in Bucharest, Romania. When designing the BEIP, the researchers wrestled with the issue of whether there was genuine equipoise regarding the relative merits of institutional and foster care. One interpretation of equipoise is that it exists when the professional community has not reached consensus about the better treatment ( Freedman, 1987 ). Childcare professionals in the United States were confident that foster care was superior, but there was no such confidence in Romania, where institutional care was the norm. Which, then, was the relevant professional community?

The equipoise requirement is justified by reference to the role morality of physicians: for a physician to give her patient treatment that she knows to be inferior would violate principles of therapeutic beneficence and nonmaleficence. As a result, the equipoise requirement has been criticized for conflating the ethics of the physician-patient relationship with the ethics of the researcher-participant relationship ( Miller and Brody, 2003 ). According to Miller and Brody (2003) , provided that other ethical requirements are met, including an honest null hypothesis, it is not unethical to assign participants to receive treatment regimens known to be inferior to the existing standard of care.

A subset of trial designs that violate equipoise are placebo-controlled trials of experimental treatments for conditions for which proven effective treatments already exist. Here, there is not equipoise because some participants will be assigned to placebo treatment, and ex hypothesi there already exists treatment that is superior to placebo. Even if we accept Miller and Brody's (2003) argument and reject the equipoise requirement, there remain concerns about these placebo-controlled trials. Providing participants with less effective treatment than they could get outside of the trial constitutes a research risk because trial participation makes them worse off. Moreover, on the face of it, a placebo-controlled trial of a novel treatment of a condition will not answer the most important scientific question about the treatment that clinicians are interested in: is this new treatment better than the old one? Consequently, in situations where there already exists a standard treatment of a condition, it has generally been considered unethical to use a placebo control when testing a new treatment, rather than using the standard treatment as an active-control ( World Medical Association, 2008 ).

Some psychiatric research provides scientific reasons to question a blanket prohibition on placebo-controlled trials when an effective intervention exists. For example, it is not unusual for antidepressive drugs to fail to show superiority to placebo in any given trial. This means that active-control trials may seem to show that an experimental drug is equivalent in effectiveness to the current standard treatment, when the explanation for their equivalence may, in fact, be that neither was better than placebo. Increasing the power of an active-control trial sufficiently to rule out this possibility may require an impractically large number of subjects and will, in any case, put a greater number of subjects at risk ( Carpenter et al., 2003 ; Miller, 2000 ). A 2005 trial of risperidone for acute mania conducted in India ( Khanna et al., 2005 ) was criticized for unnecessarily exposing subjects to risk ( Basil et al., 2006 ; Murtagh and Murphy, 2006 ; Srinivasan et al., 2006 ). The investigators' response to criticisms adopted exactly the line of argument just described:

A placebo group was included because patients with mania generally show a high and variable placebo response, making it difficult to identify their responses to an active medication. Placebo-controlled trials are valuable in that they expose the fewest patients to potentially ineffective treatments. In addition, inclusion of a placebo arm allows a valid evaluation of adverse events attributable to treatment v. those independent of treatment. ( Khanna et al., 2006 )

Concerns about the standard of care given to research participants are exacerbated in trials in developing countries, like India, where research participants may not have access to treatment independent of the study. In such cases, potential participants may have no real choice but to join a placebo-controlled trial, for example, because that is the only way they have a chance to receive treatment. In the Indian risperidone trial, the issue of exploitation is particularly stark because it seemed to some that participants were getting less than the international best standard of care, in order that a pharmaceutical company could gather data that was unlikely to benefit many Indian patients.

This is just one way in which trial design may present ethically troubling risks to participants. Other potentially difficult designs include washout studies, in which participants discontinue use of their medication, and challenge studies, in which psychiatric symptoms are experimentally induced ( Miller and Rosenstein, 1997 ). In both cases, the welfare of participants may seem to be endangered ( Zipursky, 1999 ). A variant on the standard placebo-controlled trial design is the withdrawal design, in which everyone starts the trial on medication, the people who respond to the medication are then selected for randomization, and then half of those people are randomized to placebo. This design was used by a Japanese research team to assess the effectiveness of sertraline for depression, as described by Shimon Tashiro and colleagues in this collection. The researchers regarded this design as more likely to benefit the participants because for legal reasons, sertraline was being tested in Japan despite its proven effectiveness in non-Japanese populations. Tashiro and colleagues analyze how the risks and benefits of a withdrawal design compare with those of standard placebo-controlled trials and consider whether the special regulatory context of Japan makes a difference.

Study Population

The choice of study population implicates considerations of justice. The Belmont Report, which lays out the ethical foundations for the United States system for ethical review of human subject research, says:

Individual justice in the selection of subjects would require that researchers … should not offer potentially beneficial research only to some patients who are in their favor or select only “undesirable” persons for risky research. Social justice requires that distinction be drawn between classes of subjects that ought, and ought not, to participate in any particular kind of research, based on the ability of members of that class to bear burdens and on the appropriateness of placing further burdens on already burdened persons. ( National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978 )

Two distinct considerations are highlighted here. The first (“individual justice”) requires that the researchers treat people equally. Morally irrelevant differences between people should not be the basis for deciding whom to enroll in research. For example, it would normally be unjust to exclude women from a phase 3 trial of a novel treatment of early-stage Alzheimer disease, given that they are an affected group. Some differences are not morally irrelevant, however. In particular, there may be scientific reasons for choosing one possible research population over another, and there may be risk-related reasons for excluding certain groups. For example, a functional magnetic resonance imaging study in healthy volunteers to examine the acute effects of an antianxiety medication might reasonably exclude left-handed people because their brain structure is different from that of right-handed people, and a study of mood that required participants to forego medication could justifiably exclude people with severe depression or suicidal ideation.

The second consideration requires that we consider how the research is likely to impact “social justice.” Social justice refers to the way in which social institutions distribute goods, like property, education, and health care. This may apply to justice within a state ( Rawls, 1971 ) or to global justice ( Beitz, 1973 ). In general, research will negatively affect social justice when it increases inequality, for example, by making people who are already badly off even worse off. The quotation from the Belmont Report above suggests one way in which research might violate a requirement of social justice: people who are already badly off might be asked to participate in research and so be made worse off. For example, a study examining changes in the brain caused by alcohol abuse that primarily enrolled homeless alcoholics from a shelter near the study clinic might only put at further risk this group who are already very badly off. An alternative way in which research can promote justice or injustice is through its results. Research that leads to the development of expensive new attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication is likely to do little, if anything, to make the world more just. Research on how to improve the cognitive development of orphaned children in poor environments (like the BEIP) is much more likely to improve social justice.

This last point suggests a further concern about fairness—exploitation—that frequently arises in the context of international collaborative research in developing countries. Exploitation occurs, roughly, when one party takes “unfair advantage” of the vulnerability of another. This means that the first party benefits from the interaction and does so to an unfair extent ( Wertheimer, 1996 ). These conditions may be met in international collaborative research when the burdens of research fall disproportionately on people and institutions in developing countries, but the benefits of research, such as access to new treatments, accrue to people in richer countries. A number of case studies in this collection raise this concern in one way or another. For example, Virginia Rodriguez analyzes a proposed study of the genetic basis of antisocial personality disorder run by US researchers but carried out at sites in several Latin American countries. One of the central objections raised by one of the local national research ethics committees with regard to this study was that there appeared to be few, if any, benefits for patients and researchers in the host country.

Risks and Benefits

Almost all research poses some risk of harm to participants. Participants in mental health research may be particularly susceptible to risk in several ways. First, and most obviously, they may be physically or psychologically harmed as a result of trial participation. For example, an intervention study of an experimental antipsychotic may result in some serious adverse effects for participants who take the drug. Less obvious but still very important are the potential effects of stopping medication. As mentioned above, some trials of psychoactive medications require that patients stop taking the medications that they were on before the trial ( e.g ., the Japanese withdrawal trial). Stopping their medication can lead to relapse, to dangerous behavior (like attempted suicide), and could mean that their previous treatment regimen is less successful when they attempt to return to it. Participants who were successfully treated during a trial may have similar effects if they do not have access to treatment outside of the trial. This is much more likely to happen in research conducted with poor populations, such as the Indian mania patients.

The harms resulting directly from research-related interventions are not the only risk to participants in mental health research. Participation can also increase the risks of psychosocial harms, such as being identified by one's family or community as having a particular condition. Such breaches of confidentiality need not involve gross negligence on the part of researchers. The mere fact that someone regularly attends a clinic or sees a psychiatrist could be sufficient to suggest that they have a mental illness. In other research, the design makes confidentiality hard to maintain. For example, the genetic research described by Rodriguez involved soliciting the enrollment of the family members of people with antisocial personality disorder.

The harm from a breach of confidentiality is exacerbated when the condition studied or the study population is stigmatized. Both of these were true in the case Sana Loue describes in this collection. She studied the co-occurrence of severe mental illnesses and human immunodeficiency virus risk in African-American men who have sex with men. Not only was there shame attached to the conditions under study, such that they were euphemistically described in the advertisements for the research, but also many of the participants were men who had heterosexual public identities.

Informed Consent

Many people with mental disorders retain the capacity (ability) and competence (legal status) to give informed consent. Conversely, potential participants without mental problems may lack or lose capacity (and competence). Nevertheless, problems with the ability to consent remain particularly pressing with regard to mental health research. This is partly a consequence of psychological conditions that reduce or remove the ability to give informed consent. To study these conditions, it may be necessary to use participants who have them, which means that alternative participants who can consent are, in principle, not available. This occurred in the study of South African stroke patients described by Anne Pope in this collection. The researcher she describes wanted to compare the effectiveness of exercises designed to help patients whose ability to communicate was compromised by their stroke. Given their communication difficulties and the underlying condition, there would inevitably be questions about their capacity. Whether it is permissible to enroll people who cannot give informed consent into a study depends on several factors, including the availability of alternative study populations, the levels of risk involved, and the possible benefits to participants in comparison with alternative health care they could receive.

In research that expects to enroll people with questionable capacity to consent, it is wise to institute procedures for assessing the capacity of prospective participants. There are two general strategies for making these assessments. The first is to conduct tests that measure the general cognitive abilities of the person being assessed, as an IQ test does. If she has the ability to perform these sorts of mental operations sufficiently well, it is assumed that she also has the ability to make autonomous decisions about research participation. A Mini-Mental State Examination might be used to make this sort of assessment ( Kim and Caine, 2002 ). The second capacity assessment strategy focuses on a prospective participant's understanding and reasoning with regard to the specific research project they are deciding about. If she understands that project and what it implies for her and is capable of articulating her reasoning about it, then it is clear that she is capable of consenting to participation, independent of her more general capacities. This sort of assessment requires questions that are tailored to each specific research project and cannot be properly carried out unless the assessor is familiar with that research.

Where someone lacks the capacity to give consent, sometimes a proxy decision maker can agree to trial participation on her behalf. In general, proxy consent is not equivalent to individual consent: unless the proxy was expressly designated to make research decisions by the patient while capacitated, the proxy lacks the power to exercise the patient's rights. As a result, the enrollment of people who lack capacity is only acceptable when the research poses a low net risk to participants or holds out the prospect of benefiting them. When someone has not designated a proxy decision maker for research, it is common to allow the person who has the power to make decisions about her medical care also to make decisions about research participation. However, because medical care is directed at the benefit of the patient, but research generally is not aimed at the benefit of participants, the basis for this assumption is unclear. Its legal basis may be weak, too. For example, in her discussion of research on South African stroke patients, Pope notes the confusion surrounding the legality of surrogate decision makers, given that the South African constitution forbids proxy decision making for adults (unless they have court-appointed curators), but local and international guidance documents seem to assume it.

Although it is natural to think of the capacity to give consent as an all-or-nothing phenomenon, it may be better conceptualized as domain-specific. Someone may be able to make decisions about some areas of her life, but not others. This fits with assumptions that many people make in everyday life. For example, a 10-year-old child may be deemed capable of deciding what clothes she will wear but may not be capable of deciding whether to visit the dentist. The capacity to consent may admit of degrees in another way, too. Someone may have diminished capacity to consent but still be able to make decisions about their lives if given the appropriate assistance. For example, a patient with mild dementia might not be capable of deciding on his own whether he should move in with a caregiver, but his memory lapses during decision making could be compensated for by having his son present to remind him of details relevant to the decision. The concept of supported decision making has been much discussed in the literature on disability; however, its application to consent to research has received little attention ( Herr, 2003 ; United Nations, 2007 ).

The ability to give valid informed consent is the aspect of autonomy that is most frequently discussed in the context of mental health research, but it is not the only important aspect. Several of the case studies in this collection also raise issues of voluntariness and coercion. For example, Douglas Wassenaar and Nicole Mamotte describe a study in which professors enrolled their students, which raises the question of the vulnerability of student subjects to pressure. Here, there is both the possibility of explicit coercion and the possibility that students will feel pressure even from well-meaning researchers. For various reasons, including dependence on caregivers or healthcare professionals and the stigma of their conditions, people with mental illnesses can be particularly vulnerable to coercion.

Post-Trial Obligations

The obligations of health researchers extend past the end of their study. Participants'data remain in the hands of researchers after their active involvement in a study is over, and patients with chronic conditions who enroll in clinical trials may leave them still in need of treatment.

Ongoing confidentiality is particularly important when studying stigmatized populations (such as men who have sex with men as discussed by Sana Loue) or people with stigmatizing conditions (such as bipolar disorder). In research on mental illnesses, as with many medical conditions, it is now commonplace for researchers to collect biological specimens and phenotypic data from participants to use in future research (such as genome-wide association studies). Additional challenges with regard to confidentiality are raised by the collection of data and biological specimens for future research because confidentiality must then be guaranteed in a long period of time and frequently with different research groups making use of the samples.

Biobanking also generates some distinctive ethical problems of its own. One concerns how consent to the future use of biological specimens should be obtained. Can participants simply give away their samples for use in whatever future research may be proposed, or do they need to have some idea of what this research might involve in order to give valid consent? A second problem, which arises particularly in transnational research, concerns who should control the ongoing use of the biobank. Many researchers think that biological samples should not leave the country in which they were collected, and developing country researchers worry that they will not be allowed to do research on the biobanks that end up in developed countries. This was another key concern with the proposed study in Latin America.

In international collaborative research, further questions arise as a result of the disparities between developing country participants and researchers and developed country sponsors and researchers. For example, when clinical trials test novel therapies, should successful therapies be made available after the trial? If they should, who is responsible for ensuring their provision, to whom should they be provided, and in what does providing them consist? In the case of chronic mental illnesses like depression or bipolar disorder, patient-participants may need maintenance treatment for the rest of their lives and may be at risk if treatment is stopped. This suggests that the question of what happens to them after the trial must at least be considered by those who sponsor and conduct the trial and the regulatory bodies that oversee it. Exactly on whom obligations fall remains a matter of debate ( Millum, 2011 ).

Ethics Guidelines

A number of important policy documents are relevant to the ethics of research into mental disorders. The WMA's Declaration of Helsinki and the CIOMS' Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research both consider research on individuals whose capacity and/or competence to consent is impaired. They agree on three conditions: a) research on these people is justified only if it cannot be carried out on individuals who can give adequate informed consent, b) consent to such research should be obtained from a proxy representative, and c) the goal of such research should be the promotion of the health of the population that the research participants represent ( Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, 2002 ; World Medical Association, 2008 ). In addition, with regard to individuals who are incapable of giving consent, Guideline 9 of CIOMS states that interventions that do not “hold out the prospect of direct benefit for the individual subject” should generally involve no more risk than their “routine medical or psychological examination.”

In 1998, the US National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) published a report entitled Research Involving Persons with Mental Disorders That May Affect Decision-making Capacity ( National Bioethics Advisory Commission, 1998 ). As the title suggests, this report concentrates on issues related to the capacity or competence of research participants to give informed consent. Its recommendations are largely consistent with those made in the Declaration of Helsinki and CIOMS, although it is able to devote much more space to detailed policy questions (at least in the United States context). Two domains of more specific guidance are of particular interest. First, the NBAC report considers the conditions under which individuals who lack the capacity to consent may be enrolled in research posing different levels of risk and supplying different levels of expected benefits to participants. Second, it provides some analysis of who should be recognized as an appropriate proxy decision maker (or “legally authorized representative”) for participation in clinical trials.

Finally, the World Psychiatric Association's Madrid Declaration gives guidelines on the ethics of psychiatric practice. This declaration may have implications for what is permissible in psychiatric research, insofar as the duties of psychiatrists as personal physicians are also duties of psychiatrists as medical researchers. It also briefly considers the ethics of psychiatric research, although it notes only the special vulnerability of psychiatric patients as a concern distinctive of mental health research ( World Psychiatric Association, 2002 ).

The opinions expressed are the author's own. They do not reflect any position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service, or Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosure : The author declares no conflict of interest.

- Basil B, Adetunji B, Mathews M, Budur K. Trial of risperidone in India—concerns. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 188 :489–490. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beitz C. Political theory and international relations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1973. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carpenter WT, Appelbaum PS, Levine RJ. The Declaration of Helsinki and clinical trials: A focus on placebo-controlled trials in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160 :356–362. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cash R, Wikler D, Saxena A, Capron A, editors. Casebook on ethical issues in international health research. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547727_eng.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS on behalf of the Scientific Advisory Board and the Executive Committee of the Grand Challenges on Global Mental Health. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011; 475 :27–30. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. The international ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. [Accessed on January 31, 2012]; 2002 Available at: http://www.cioms.ch/publications/layout_guide2002.pdf . [ PubMed ]

- DuBois JM. Ethical research in mental health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000; 283 :2701–2711. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freedman B. Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317 :141–145. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herr SS. Self-determination, autonomy, and alternatives for guardianship. In: Herr SS, Gostin LO, Koh HH, editors. The human rights of persons with intellectual disabilities: Different but equal. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 429–450. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoagwood K, Jensen PS, Fisher CB. Ethical issues in mental health research with children and adolescents. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hyman S, Chisholm D, Kessler R, Patel V, Whiteford H. Chapter 31: Mental disorders. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd. Washington, DC; New York, NY: Oxford University Press and the World Bank; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, Garrido-Cumbrera M, Seedat S, Mari JJ, Sreenivas V, Saxena S. Global Mental Health 4: Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet. 2007; 370 :1061–1077. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Joffe S, Truog RD. Equipoise and randomization. In: Emanuel EJ, Grady C, Crouch RA, Lie RK, Miller FG, Wendler D, editors. The oxford textbook of clinical research ethics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 245–260. [ Google Scholar ]

- Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, Grossman F, Eerdekens M, Kramer M. Risperidone in the treatment of acute mania: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005; 187 :229–234. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, Grossman F, Kramer M, Eerdekens M. Trial of risperidone in India—concerns. Authors' reply. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 188 :491. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim SYH, Caine ED. Utility and limits of the Mini Mental State Examination in evaluating consent capacity in Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatr Serv. 2002; 53 :1322–1324. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Global Mental Health 6: Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet. 2007; 370 :1241–1252. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavery J, Grady C, Wahl ER, Emanuel EJ, editors. Ethical issues in international biomedical research: A casebook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller FG, Rosenstein DL. Psychiatric symptom-provoking studies: An ethical appraisal. Biol Psychiatry. 1997; 42 :403–409. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller FG. Placebo-controlled trials in psychiatric research: An ethical perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2000; 47 :707–716. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller FG, Brody H. A critique of clinical equipoise: Therapeutic misconception in the ethics of clinical trials. Hastings Cent Rep. 2003; 33 :19–28. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Millum J. Post-trial access to antiretrovirals: Who owes what to whom? Bioethics. 2011; 25 :145–154. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murtagh A, Murphy KC. Trial of risperidone in India—concerns. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 188 :489. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Research involving persons with mental disorders that may affect decision-making capacity. [Accessed January 31, 2012]; 1998 Available at: http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/nbac/capacity/toc.htm .

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Washington, DC: DHEW Publication; 1978. pp. 78–0012. No. (OS) [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, Hosman C, McGuire H, Rojas G, van Ommeren M. Global Mental Health 3: Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007; 370 :991–1005. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, Rahman A. Global Mental Health 1: No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007; 370 :859–877. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rawls J. A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1971. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thiers FA, Sinskey AJ, Berndt ER. Trends in the globalization of clinical trials. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2008; 7 :13–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Srinivasan S, Pai SA, Bhan A, Jesani A, Thomas G. Trial of risperidone in India—concerns. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 188 :489. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- United Nations. Legal capacity and supported decision-making in from exclusion to equality: Realizing the rights of persons with disabilities. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 2007. Available at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=242 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiss MG, Jadhav S, Raguram R, Vounatsou P, Littlewood R. Psychiatric stigma across cultures: Local validation in Bangalore and London. Anthropol Med. 2001; 8 :71–87. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wertheimer A. Exploitation. Princeton, UK: Princeton University Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization. Glaring inequalities for people with mental disorders addressed in new WHO effort. [Accessed January 31, 2012]; 2005a Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2005/np14/en/index.html .

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas: 2005. [Accessed January 31, 2012]; 2005b Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/mhatlas05/en/index.html .

- World Medical Association. The Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. [Accessed January 31, 2012]; 2008 Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html .

- World Psychiatric Association. Madrid Declaration on Ethical Standards for Psychiatric Practice. [Accessed January 31, 2012]; 2002 Available at: http://www.wpanet.org/detail.php?section_id=5&content_id=48 .

- Zipursky RB. Ethical issues in schizophrenia research. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 1999; 1 :13–19. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Ethics & Psychology: Case Studies

- General Resources

- Animal Subjects

- Human Subjects

- Case Studies

Collections of Cases

- Ethics Case Studies in Mental Health Research A large collection of cases addressing issues such as human participants in research, conflict of interest, and the responsible collection, management, and use of research data.

- Ethics Education Library -Psychology Case Studies A collection of over 90 case studies from the Ethics Education Library.

- Ethics Rounds A collection of case studies published in the American Psychological Association's "Monitor on Ethics".

Case Investigations by Government Agencies/Professional Organizations

- Office of Research Integrity Cases summaries from the past four years of investigations and inquiries done by the Office of Research Integrity. Also includes short case summaries from 1994 onwards.

Books, Anthologies, & More

- << Previous: Human Subjects

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 10:40 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/psychologyethics

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

APA Code of Ethics: Principles, Purpose, and Guidelines

What to know about the APA's ethical codes that psychologists follow

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Mediaphotos / Getty Images

- What and Who the Code of Ethics Is For?

- The 5 Ethical Principles

- The 10 Standards

- What Happens If a Therapist Violates the APA's Ethical Codes?

- How Can I Report a Therapist?

Ethical Considerations

The APA Code of Ethics guides professionals working in psychology so that they're better equipped with the knowledge of what to do when they encounter some moral or ethical dilemma. Some of these are principles or values that psychologists should aspire to uphold. In other cases, the APA outlines standards that are enforceable expectations.

Ethics are an important concern in psychology, particularly regarding therapy and research. Working with patients and conducting psychological research can pose various ethical and moral issues that must be addressed.

Understanding the APA Code of Ethics

The American Psychological Association (APA) publishes the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct which outlines aspirational principles as well as enforceable standards that psychologists should use when making decisions.

In 1948, APA president Nicholas Hobbs said, "[The APA Code of Ethics] should be of palpable aid to the ethical psychologist in making daily decisions."

In other words, these ethical codes are meant to guide mental health professionals in making the best ethical decisions on a regular basis.

When Did the APA Publish Its Code of Ethics?

The APA first published its ethics code in 1953 and has been continuously evolving the code ever since.

What's in the APA's Code of Ethics?

The APA code of ethics is composed of key principles and ethical standards:

- Principles : The principles are intended as a guide to help inspire psychologists as they work in their profession, whether they are working in mental health, in research , or in business.

- Standards : The standards outline expectations of conduct. If any of these are violated, it can result in professional and legal ramifications.

Who Is the APA Code of Ethics For?

The code of ethics applies only to work-related, professional activities including research, teaching, counseling , psychotherapy, and consulting. Private conduct is not subject to scrutiny by the APA's ethics committee.

APA's Ethical Codes: The Five Ethical Principles

Not all ethical issues are clear-cut, but the APA strives to offer psychologists guiding principles to help them make sound ethical choices within their profession.

The APA Code of Ethics' Five Principles

- Principle A : Beneficence and Non-Maleficence

- Principle B : Fidelity and Responsibility

- Principle C : Integrity

- Principle D : Justice

- Principle E : Respect for People's Rights and Dignity

Principle A: Beneficence and Non-Maleficence

The first principle of the APA ethics code states that psychologists should strive to protect the rights and welfare of those with whom they work professionally . This includes the clients they see in clinical practice, animals that are involved in research and experiments , and anyone else with whom they engage in professional interaction.

This principle encourages psychologists to strive to eliminate biases , affiliations, and prejudices that might influence their work. This includes acting independently in research and not allowing affiliations or sponsorships to influence results.

Principle B: Fidelity and Responsibility

Principle B states that psychologists have a moral responsibility to help ensure that others working in their profession also uphold high ethical standards . This principle suggests that psychologists should participate in activities that enhance the ethical compliance and conduct of their colleagues.

Serving as a mentor, taking part in peer review, and pointing out ethical concerns or misconduct are examples of how this principle might be put into action. Psychologists are also encouraged to donate some of their time to the betterment of the community.

Principle C: Integrity

This principle states that, in research and practice, psychologists should never attempt to deceive or misrepresent . For instance, in research, deception can involve fabricating or manipulating results in some way to achieve desired outcomes. Psychologists should also strive for transparency and honesty in their practice.

Principle D: Justice

The principle of justice says that mental health professionals have a responsibility to be fair and impartial. It also states that people have a right to access and benefit from advances that have been made in the field of psychology. It is important for psychologists to treat people equally.

Psychologists should also always practice within their area of expertise and also be aware of their level of competence and limitations.

Principle E: Respect for People's Rights and Dignity

Principle E states that psychologists should respect the right to dignity, privacy, and confidentiality of those they work with professionally . They should also strive to minimize their own biases as well as be aware of issues related to diversity and the concerns of particular populations.

For example, people may have specific concerns related to their age, socioeconomic status, race , gender, religion, ethnicity, or disability.

The APA Code of Ethics' Standards

The 10 standards found in the APA ethics code are enforceable rules of conduct for psychologists working in clinical practice and academia.

The 10 Standards Found in the APA Code of Ethics

- Resolving Ethical Issues

- Human Relations

- Privacy and Confidentiality

- Advertising and Other Public Statements

- Record Keeping and Fees

- Education and Training

- Research and Publication

These standards tend to be broad in order to help guide the behavior of psychologists across a wide variety of domains and situations.

They apply to areas such as education, therapy, advertising, privacy, research, and publication.

1: Resolving Ethical Issues

This standard of the APA ethics code provides information about what psychologists should do to resolve ethical situations they may encounter in their work. This includes advice for what researchers should do when their work is misrepresented and when to report ethical violations.

2: Competence

It is important that psychologists practice within their area of expertise. When treating clients or working with the public, psychologists must make it clear what they are trained to do as well as what they are not trained to do.

An Exception to This Standard

This standard stipulates that in an emergency situation, professionals may provide services even if it falls outside the scope of their practice in order to ensure that access to services is provided.

3: Human Relations

Psychologists frequently work with a team of other mental health professionals. This standard of the ethics code is designed to guide psychologists in their interactions with others in the field.

This includes guidelines for dealing with sexual harassment, and discrimination, avoiding harm during treatment and avoiding exploitative relationships (such as a sexual relationship with a student or subordinate).

4: Privacy and Confidentiality

This standard outlines psychologists’ responsibilities with regard to maintaining patient confidentiality . Psychologists are obligated to take reasonable precautions to keep client information private.

However, the APA also notes that there are limitations to confidentiality. Sometimes psychologists need to disclose information about their patients in order to consult with other mental health professionals, for example.

While there are cases where information is divulged, psychologists must strive to minimize these intrusions on privacy and confidentiality.

5: Advertising and Other Public Statements

Psychologists who advertise their services must ensure that they accurately depict their training, experience, and expertise. They also need to avoid marketing statements that are deceptive or false.

This also applies to how psychologists are portrayed by the media when providing their expertise or opinion in articles, blogs, books, or television programs.

When presenting at conferences or giving workshops, psychologists should also ensure that the brochures and other marketing materials for the event accurately depict what the event will cover.

6: Record Keeping and Fees

Maintaining accurate records is an important part of a psychologist’s work, whether the individual is working in research or with patients. Patient records include case notes and other diagnostic assessments used in the course of treatment.

In terms of research, record-keeping involves detailing how studies were performed and the procedures that were used. This allows other researchers to assess the research and ensures that the study can be replicated.

7: Education and Training

This standard focuses on expectations for behavior when psychologists are teaching or training students.

When creating courses and programs to train other psychologists and mental health professionals , current and accurate evidence-based research should be used.

This standard also states that faculty members are not allowed to provide psychotherapy services to their students.

8: Research and Publication

This standard focuses on ethical considerations when conducting research and publishing results .

For example, the APA states that psychologists must obtain approval from the institution that is carrying out the research, present information about the purpose of the study to participants, and inform participants about the potential risks of taking part in the research.

9: Assessment

Psychologists should obtain informed consent before administering assessments. Assessments should be used to support a psychologist’s professional opinion, but psychologists should also understand the limitations of these tools. They should also take steps to ensure the privacy of those who have taken assessments.

10: Therapy

This standard outlines professional expectations within the context of providing therapy. Areas that are addressed include the importance of obtaining informed consent and explaining the treatment process to clients.

Confidentiality is addressed, as well as some of the limitations to confidentiality, such as when a client poses an immediate danger to himself or others.

Minimizing harm, avoiding sexual relationships with clients, and continuation of care are other areas that are addressed by this standard.

For example, if a psychologist must stop providing services to a client for some reason, psychologists are expected to prepare clients for the change and help locate alternative services.

What Happens If a Therapist Violates the APA's Ethical Codes?

After a report of unethical conduct is received, the APA may censure or reprimand the psychologist, or the individual may have his or her APA membership revoked. Complaints may also be referred to others, including state professional licensing boards.

State psychological associations, professional groups, licensing boards, and government agencies may also choose to impose penalties against the psychologist.

Health insurance agencies and state and federal payers of health insurance claims may also pursue action against professionals for ethical violations related to treatment, billing, or fraud.

Those affected by ethical violations may also opt to seek monetary damages in civil courts.

Illegal activity may be prosecuted in criminal courts. If this results in a felony conviction, the APA may take further actions including suspension or expulsion from state psychological associations and the suspension or loss of the psychologist's license to practice.

How Can I Report a Therapist for Unethical Behavior?

While unfortunate, there are instances in which a therapist may commit an ethical violation. If you would like to file a complaint against a therapist, you can do so by contacting your state's psychologist licensing board.

How to Find Your State's Psychologist Board

Here is a list of the U.S. psychology boards . Choose your state and refer to the contact information provided.

Because psychologists often deal with extremely sensitive or volatile situations, ethical concerns can play a big role in professional life.

The most significant ethical issues include the following:

- Client Welfare : Due to the role they serve, psychologists often work with individuals who are vulnerable due to their age, disability, intellectual ability, and other concerns. When working with these individuals, psychologists must always strive to protect the welfare of their clients.

- Informed Consent : Psychologists are responsible for providing a wide range of services in their roles as therapists, researchers, educators, and consultants. When people are acting as consumers of psychological services, they have a right to know what to expect. In therapy, obtaining informed consent involves explaining what services are offered, what the possible risks might be, and the patient’s right to leave treatment. When conducting research, informed consent involves letting participants know about any possible risks of taking part in the research.

- Confidentiality : Therapy requires providing a safe place for clients to discuss highly personal issues without fear of having this information shared with others or made public. However, sometimes a psychologist might need to share some details such as when consulting with other professionals or when they are publishing research. Ethical guidelines dictate when and how some information might be shared, as well as some of the steps that psychologists should take to protect client privacy.

- Competence : The training, education, and experience of psychologists is also an important ethical concern. Psychologists must possess the skill and knowledge to properly provide the services that clients need. For example, if a psychologist needs to administer a particular assessment in the course of treatment, they should have an understanding of both the administration and interpretation of that specific test.

While ethical codes exist to help psychologists, this does not mean that psychology is free of ethical controversy today. Current debates over psychologists’ participation in torture and the use of animals in psychological research remain hot-button ethical concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

You can read the APA's Code of Ethics on the American Psychological Association's website here .

If you would like to ask a question about the APA's ethical codes, you can do so on their website here .

American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Including 2010 and 2016 Amendments. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association 2020 https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

Hobbs N. The development of a code of ethical standards for psychology . American Psychologist. 1948;3(3):80–84.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0060281

Conlin WE, Boness CL. Ethical considerations for addressing distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56(4):449-458. doi:10.1037/pst0000252

Stark L. The science of ethics: Deception, the resilient self, and the APA code of ethics, 1966-1973. J Hist Behav Sci . 2010;46(4):337-370. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20468

Smith RD, Holmberg J, Cornish JE. Psychotherapy in the #MeToo era: Ethical issues . Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56(4):483-490. doi:10.1037/pst0000262

Erickson Cornish JA, Smith RD, Holmberg JR, Dunn TM, Siderius LL. Psychotherapists in danger: The ethics of responding to client threats, stalking, and harassment. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56(4):441-448. doi:10.1037/pst0000248

American Psychological Association. Complaints regarding APA members .

American Psychological Association. Council Policy Manual. Policy Related to Psychologists' Work in National Security Settings and Reaffirmation of the APA Position Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Adopted by APA Council of Representatives, August 2013. Amended by APA Council of Representatives, August 2015. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association 2020 https://www.apa.org/about/policy/national-security

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Dual-Process Theories in Moral Psychology pp 139–158 Cite as

Psychology’s Contribution to Ethics: Two Case Studies

- Liz Gulliford 2

- First Online: 22 March 2016

724 Accesses

1 Citations