Business Finance

Finance Business

Business Health

Technology Business

How Businesses Can Solve Social Problems

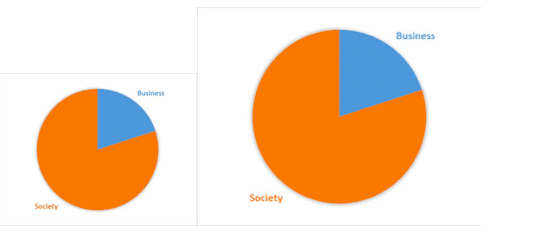

For many entrepreneurs, making a profit is the most significant goal for their businesses. While there’s nothing wrong with this mindset, business owners must also remember that their enterprises have a much bigger purpose in today’s society. There’s no denying that the world is in dire straits. Climate change, famine, lack of adequate healthcare, and excess pollution are just a few of the countless social problems that wreak havoc on humanity. Although it may seem quite unlikely, businesses can solve most, if not all, of these social ills.

“Being serious about running a business is not only about the growth and maximizing revenue. It is equally caring about your community and giving it a helping hand at challenging times”, says Gevorg Hambardzumyan, CEO of Front Signs sign company which switched its production to manufacturing face shields and donating them to hospitals in times of COVID-19 outbreak. Similarly, many other companies can follow suit and lend a helping hand in one way or another.

More businesses should get involved in solving social inadequacies because they are the root cause of some. We’ve all heard of companies that operate with poor ethics and exploit customers because of only focusing on the bottom line. Such enterprises repeal the efforts that responsible individuals place in the fight against social defects. For this reason, it’s only fair that companies step up and join in the battle to eradicate the world’s social problems. This article explores the many ways in which businesses can help solve the issues tearing the world apart. Therefore, if you’re a skeptic or an entrepreneur with a passion for making a difference, this article will point you in the right direction.

What Can Businesses Do?

Although the societal ills we face in this day and age can be overwhelming, we have everything we need to ensure we overcome them. The technology and resources within reach of business owners can be of immense assistance in ridding the world of its inadequacies. Here are just some of the many ways that companies can contribute to this cause.

Leverage New Technologies to Solve Problems

There’s no denying that technology has taken a grand leap forward in the last couple of decades. Nowadays, the technology available doesn’t only help entrepreneurs improve their products and services but also find innovative ways of enhancing sustainability. The technology used to solve simple problems within a business, regardless of how small it may seem, can solve global predicaments. The solutions that contemporary technology has produced for companies such as; efficient energy production and remote accessibility can easily find worldwide applications.

Increased Collaborations

The world today is more connected than ever before. Companies can coordinate operations with partners from other countries with incredible ease. With this newfound connectivity, entrepreneurs have access to more impactful resources that can make global differences. For instance, businesses in hunger-stricken countries can develop an international forum with foreign partners to create solutions. In this case, global collaborations can assist in eradicating social ills by providing input from other cultures. Another way to go about this is by partnering companies with philanthropists and donors in fighting social ills. A recent report by The Harvard Business Review highlighted how a company in Pennsylvania made significant strides when battling modern-day slavery by partnering with nonprofit organizations. The review depicts how the collaboration of businesses and charitable institutions can tremendously impact societal issues.

The Entrepreneurial Mindset

Entrepreneurs are natural problem-solvers. The very essence of entrepreneurship is finding a problem in society and providing the solution as a business. Company owners have an unrelenting mindset that embraces audacious goals and is willing to learn from mistakes. What’s more, all entrepreneurs can only attain success by finding a way to use the available resources to solve problems. Better yet, astute entrepreneurs go a step further by coming up with new tools to solve issues. This type of mindset is what the world requires to ensure it rids itself of all social predicaments. While not all enterprises may be financially able to combat social ills, all entrepreneurs can chip in by providing innovative ideas to eradicate these problems.

Consumer Influence

Due to the influx of pollution and other environmental effects, consumers are becoming more mindful of the products they use. What’s more, nowadays people want to know more about the companies they frequently use. Furthermore, given that modern technology has made people more aware of social issues, consumers have begun being more responsible about what they purchase. For this reason, companies have become more compelled to give back to the community. According to a study, close to 90 percent of consumers buy products from companies that support a cause they care about. This report reflects consumers’ desire to purchase products from companies that positively impact society. Moreover, enterprises that show commitment to sustainability display a higher annual growth rate than their non-sustainable counterparts.

How Businesses Can Benefit

While we have established that businesses can lend a helping hand when solving social problems, some people still cling to the notion that companies profit by causing these problems. Instead, the contrary is true; businesses benefit by solving social difficulties. Companies actively involved in fighting social obstacles benefit from the excellent image they build for themselves and much more. Furthermore, as technology continues to grow and make us aware of pressing social issues, consumers will be more cautious about what they buy. Consequently, we are likely to see more businesses getting involved in solving social inadequacies. In turn, this promotes positive brand perception and increases sales.

However, balancing profit and purpose when running a business isn’t a walk in the park. Given that more than 70 percent of startups fail, enterprises focused on social values and the bottom are at a higher risk of failure. Nevertheless, many companies have done it before, and many more are also yet to do it.

Final Thoughts

The notion that profit can only be measured by monetary gain is grossly misguided. While businesses need to make a profit for them to remain operational, they also have a social responsibility to fulfill. For entrepreneurs interested in causing a difference, following the tips outlined in this article is a step in the right direction.

Five Essential Metrics for Online Store Profitability

How to start a locksmith business and market it effectively?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Text Translator

Awards Ceremony

Click on the Image to view the Magazine

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

How to Create Social Change: 4 Business Strategies

- 24 Jan 2019

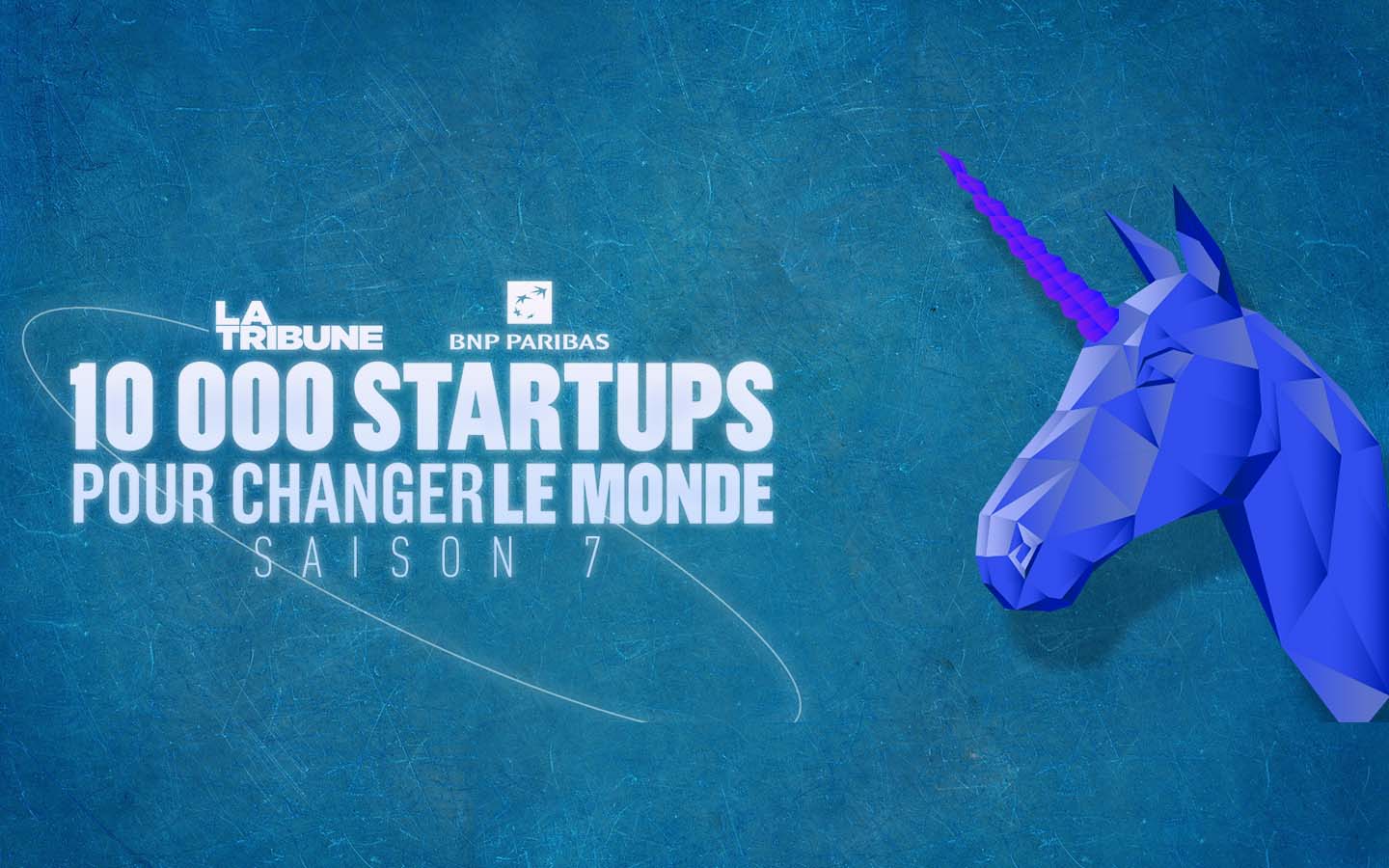

Monumental challenges, such as climate change, social injustice, and poverty, are inspiring people worldwide to take action and find ways to better their communities and society at large. As efforts to solve these issues have grown over time, so, too, has the role businesses play in driving social change.

According to Harvard Business School Professor Rebecca Henderson, who teaches the online course Sustainable Business Strategy , companies are starting to realize the importance of thinking long-term and considering the social impact of their products and services.

“This realization is arriving not a moment too soon,” Henderson writes in the Harvard Business Review . “The world badly needs a more sustainable form of capitalism if we’re going to build a more inclusive, prosperous society and avoid catastrophic climate change.”

Access your free e-book today.

What Does Social Impact Mean?

Before setting out to drive change, it’s important to understand what the term “social impact” means. Positive social impact refers to the ways that businesses and individuals take action to address issues facing their communities.

To bring about social change, business leaders must identify the core values that motivate them to act. Those values are often focused on issues such as climate change, poverty, and other pressing social and environmental challenges impacting society. With values informing their decision-making and strategy, purpose-driven leaders can feel empowered to make a difference.

Working toward positive social change can mutually benefit businesses and the communities they operate within. Consulting firm Deloitte has outlined six drivers of business value that directly relate to social impact: brand differentiation, talent attraction and retention, innovation, operational efficiency, risk mitigation, and capital access and market valuation.

For business leaders seeking to make a difference, now is the time to act. Here are four accessible ways companies can be more purpose-driven and positively impact society.

Related: How Can Purpose Impact Business Performance?

Business Strategies for Social Change

1. engage in and promote ethical business practices.

To effect change externally, companies need to first look internally and ensure that a commitment to social responsibility is embedded in their business operations.

For manufacturing giant General Electric (GE), a presence in the global marketplace creates conditions that require the company to regularly confront complex human rights issues . To overcome these challenges, GE works to prevent forced labor through its Ethical Supply Chain Program (pdf) , and practices responsible sourcing through a pledge to eliminate the use of “conflict minerals” (pdf) —mined materials that finance armed factions and human rights abuses—in its products. Through these initiatives, the company has bolstered its sustainability strategy and encouraged business partners to follow suit, with the goal of enacting system-level change.

GE serves as a prime example of how working for the greater good starts with leading by example. Companies seeking to do the same should consider how they can be more ethical in their sourcing and production processes, and use social responsibility as a lens through which to reform their business practices.

Related: What Does "Sustainability" Mean in Business?

2. Form Strategic Partnerships with Nonprofit Organizations

Influencing systemic change is no easy task. It requires a deep understanding of the problems facing society and steadfastness to overcome them.

Strategically partnering with nonprofit organizations that directly tackle the world’s most pressing challenges can be an effective way for companies to boost their social impact.

An example is the partnership between Peet’s Coffee and Technoserve, a nonprofit that helps people in developing countries lift themselves out of poverty by building competitive farms, businesses, and industries. Together, the organizations spearhead the Farmer Assistance Program , an initiative that focuses on training smallholder farmers to produce high-quality coffee.

Through the collaboration, farmers in countries like Ethiopia, Guatemala, and Rwanda have been equipped with business skills and knowledge of environmental sustainability best practices, enabling them to improve their lives and communities.

This joint effort illustrates the great strides that can be made when for-profit and not-for-profit firms combine their resources to work for the greater good.

Related: Lessons on Corporate Social Responsibility From New Transportation Partnership

3. Encourage Employees to Volunteer

Being a purpose-driven firm requires an adherence to social responsibility that goes deeper than the organizational level. Employees need to share in the company’s vision for change and feel that their contributions are meaningful.

Encouraging employees to volunteer is a practical way to involve staff in social impact initiatives and boost morale. In a recent survey by Deloitte (pdf) , 74 percent of workers said they believe volunteerism provides an improved sense of purpose.

At organic food producer Clif Bar, volunteering is an integral part of the company’s business model. Through the CLIF CORPS program, employees are encouraged to dedicate their time to issues and organizations that are important to them—and during work hours.

In 2017, Clif Bar achieved a major milestone when it reached 100,000 hours of community service —the equivalent to paying 48 employees to volunteer full-time for one year.

By fostering a culture that inspirits employees to give back, companies can empower their workforce to engage with issues that matter to them and instill a sense of shared purpose.

4. Inspire Action with Corporate Platforms

Beyond implementing programs and initiatives to address global problems, using platforms like blogs and social media channels as advocacy tools can be a powerful way for businesses to push for change.

Outdoor clothing manufacturer Patagonia is one example of an organization that uses its far-reaching corporate voice to raise awareness of the challenges facing society, most notably surrounding climate change .

On its blog The Cleanest Line , Patagonia recently advocated for protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from development and, in the past, has voiced its support for such events as the People’s Climate March .

In addition, the company launched Patagonia Action Works in 2017, an online platform that connects people to nearby environmental activism opportunities. Since the tool’s inception, it’s been used to support grassroots campaigns to defend wild buffalo in Montana and preserve Oregon’s high desert , among other efforts.

Patagonia’s work to combat climate change represents the type of influence companies can have when they resourcefully use their communication platforms to inspire collective action.

Taking a Values-Driven Approach to Business

Large-scale change doesn’t happen overnight. Solving the world’s major social and environmental problems takes time and effort. But through a purpose-driven approach to business, companies can help create a more just and sustainable future.

Do you want to help your organization drive system-level change? Explore our three-week online course Sustainable Business Strategy and find out how you can become a purpose-driven leader.

(This post was updated on November 24, 2020. It was originally published on January 24, 2019.)

About the Author

How businesses can help solve society’s workforce problems

We have all adapted quickly to remote working – these skills will be invaluable as roles continue to change in the future. Image: Freepik.

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Bhushan Sethi

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of work.

- COVID-19 has presented major challenges for organizations: adapting workplaces, supporting remote workers, furlough schemes and redundancies.

- Society must work collaboratively to build sustainable work solutions for a future where some occupations will cease to exist and others will have to adapt to survive.

- HR leaders are uniquely positioned to help steer this model – working with communities, schools and governments – to rebuild the economy.

In the past nine months, I’ve been proud to see so many businesses stepping up to help their employees and communities. From rolling out new benefits and programmes aimed at helping people navigate the pandemic to making layoffs a last resort , businesses of all types have led with purpose and empathy.

Now, with new vaccines offering hope for an end to the pandemic, business leaders have an opportunity to extend that sense of purpose by helping to find sustainable solutions to society’s workforce problems. That includes one of the biggest challenges our economy faces: how can we get the unemployed back to work?

Have you read?

This is how we build a future-ready workforce for the post-covid world, 4 ways to reskill the global workforce – and this is where it’s already happening , why collaboration will be key to creating the workforce of the future.

Millions of people have lost their jobs during the pandemic, and many companies are continuing to consider and possibly make layoffs . But getting back to work isn’t simply a matter of finding another job. The pandemic has disrupted whole industries – including restaurants, travel and retail – and many of those jobs are not likely to come back. That means many of those employees will need to reskill and move into a new occupation.

Meanwhile, as companies accelerate their automation plans and many jobs continue to be remote for the foreseeable future, employees across every sector should acquire new skills to think and work in different ways.

There are other pressing workforce challenges too: immigration, employee health and workplace safety, societal racial and gender-based job discrimination, job security and more.

These are big problems to address. That’s why businesses should play a leading role in working with communities, schools and policymakers at every level to find sustainable solutions. No one has more experience – or more at stake – in the nation’s economic health than its business leaders. Given that President Biden’s administration is expected to make workforce issues like fair pay, minimum wages and labour unions a significant part of its policy agenda, now may be a prime opportunity for business leaders to get more involved. It’s also the right thing to do.

Within your organization, you probably already have someone who is ready to help your business take the lead on this initiative – your chief human resources officer (CHRO).

The first global pandemic in more than 100 years, COVID-19 has spread throughout the world at an unprecedented speed. At the time of writing, 4.5 million cases have been confirmed and more than 300,000 people have died due to the virus.

As countries seek to recover, some of the more long-term economic, business, environmental, societal and technological challenges and opportunities are just beginning to become visible.

To help all stakeholders – communities, governments, businesses and individuals understand the emerging risks and follow-on effects generated by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, the World Economic Forum, in collaboration with Marsh and McLennan and Zurich Insurance Group, has launched its COVID-19 Risks Outlook: A Preliminary Mapping and its Implications - a companion for decision-makers, building on the Forum’s annual Global Risks Report.

Companies are invited to join the Forum’s work to help manage the identified emerging risks of COVID-19 across industries to shape a better future. Read the full COVID-19 Risks Outlook: A Preliminary Mapping and its Implications report here , and our impact story with further information.

HR leaders are primed and ready to help

Human resources (HR) leaders have been at the epicenter of their companies’ pandemic responses. In hundreds of conversations with CHROs over the past nine months, I’ve been impressed with the depth and scope of new responsibilities they’ve undertaken. They’ve led on complex issues like employee safety and mental health, productivity and morale. They were pivotal in the transition to remote work, and they’ve helped their organizations’ leaders navigate hard choices about furloughs and severance.

CHROs’ leadership during the pandemic has also earned many of them new clout within their organizations – influence they can use to encourage other business leaders to turn their attention outward.

Many CHROs are up for the challenge. In November’s PwC Pulse Survey, an overwhelming number of CHROs – 89% – said they want to engage with elected officials to raise awareness of President Biden’s campaign tax proposals on their business operations. That’s compared with 78% of respondents across all business leaders.

This isn’t about lobbying for better business policies or tax breaks. It’s about finding solutions that are good for all stakeholders – your own business, as well as shareholders, employees, customers and communities. Some corporate boards have already begun to make this a priority; now there’s an opportunity for other leaders within the organization to get involved as well. Collaborating with schools, community organizations and governments can help you get started.

- Schools: community colleges, universities and even some high schools are ideally suited for working with corporations. Businesses can offer experience and support to provide training, job shadowing and internships – not just for entry-level jobs, but possibly for professional careers.

- Community organizations: collaboration with community organizations can help address the problems that may be the most pressing in your area, such as a need to reskill employees, help people develop their cyber or digital acumen , or other challenges. This could involve working with nonprofits or chambers of commerce, many of which are developing new ideas for economic and workforce development, improved access to education for minority groups and other issues.

- Governments: businesses have an opportunity to help shape the future of work for the good of society and help themselves in the process. Offer your experience and acumen to political leaders who are brainstorming policies to help create jobs and provide training to those who are unemployed.

The workforce challenges facing society today can be daunting. Finding creative, sustainable solutions requires diverse ways of thinking and collaborating. Businesses – with CHROs at the centre – should be part of that effort.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Future of Work .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

The six drivers of employee health every employer should know

Jacqueline Brassey, Lars Hartenstein, Patrick Simon and Barbara Jeffery

April 3, 2024

Remote work curbs salaries - new data

Victoria Masterson

March 25, 2024

Women inventors make gains, but gender gaps remain

March 19, 2024

6 work and workplace trends to watch in 2024

Kate Whiting

February 6, 2024

How using genAI to fuse creativity and technology could reshape the way we work

Kathleen O'Reilly

January 24, 2024

What do workers need to learn to stay relevant in the age of AI? Chief learning officers explain

Aarushi Singhania

January 19, 2024

The case for letting business solve social problems

- social change

- communication

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Should Businesses Take a Stand on Societal Issues?

If you’re a leader, ask yourself these questions to help you decide whether to engage on societal issues.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Should businesses take a stand for or against particular societal issues? And how should leaders determine when and how to engage on these sensitive matters?

Harvard Business School senior lecturer Hubert Joly , who led the electronics retailer Best Buy for almost a decade, discusses examples of corporate leaders who had to determine whether and how to engage with humanitarian crises, geopolitical conflict, racial justice, climate change, and more in the case, “ Deciding When to Engage on Societal Issues .”

BRIAN KENNY: In case you’ve ever thought about becoming a CEO, your job description might include things like, work with the board of directors to set goals for the firm, oversee finances, manage the entire operation and ensure compliance with laws and regulations, negotiate big deals like mergers and acquisitions. And if it’s a public company, you’d have to do quarterly earnings and of course, generate profits. All of these would be pretty standard parts of your job. Not explicitly mentioned, but definitely expected these days would also be something like wade into fraught social issues that seemingly have nothing to do with your day-to-day business and could potentially put you in the center of a political tsunami. Good luck with that. Today on Cold Call, we welcome Professor Hubert Joly to discuss the case, “Deciding when to engage on societal issues.” I’m your host, Brian Kenny, and you’re listening to Cold Call on the HBR Podcast Network. Hubery Joly is a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School and the former chairman and chief executive officer of Best Buy. He is also the author of The Heart of Business: Leadership Principles for the Next Era of Capitalism , and he is a repeat customer on Cold Call . Welcome, Hubert.

HUBERY JOLY: Well, thank you for having me, Brian. I look forward to our conversation.

BRIAN KENNY: Great to have you back, and I really enjoyed reading this case. So, thank you for writing it and thank you for coming on to talk about it. Let me ask you to start just by telling us what’s the central issue in the case and what’s your cold call when you start the discussion in class?

HUBERY JOLY: The central issue is of course, when and how to engage on some of these potentially controversial but important societal issues, knowing that doing nothing, ignoring these issues can be very dangerous and engaging can be also risky. And so, maybe the cold call would be, what criteria would you use to decide when and how to engage?

BRIAN KENNY: So, I do want to ask you about, a little bit later in the conversation, whether you’ve had to tow this line before? But before we get there, let me just ask you why you decided to write the case and how does it factor into the kinds of things that you’re thinking about as a professor at Harvard Business School?

HUBERY JOLY: Yeah. So, my focus is leadership matters, either supporting CEOs or senior leaders in Executive Education, and of course, future leaders in the MBA program. And as you indicated, Brian, this is a new field and a field where landmines have been dropped. And so this is new territory and in many ways, CEOs, leaders have not been prepared, right? When they went to school 20 or 30 years ago, it was not quite the same. So, writing this case provided the opportunity to review a number of instances where CEOs decided to engage and with of course, varying results. And of course, in the Socratic method that we love at HBS and also love Aristotle, you start from reality and you try to derive some principles. So again, you cannot ignore these facts, you might as well engage in this matter.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. And it’s unlike other Harvard Business School cases to the extent that it’s not really a narrative. There’s not like a one continuous story here. This is just mini chapters of the situation, and you lay it out beautifully and just very factual form. So, I thought it was an interesting departure. There’s been a lot of discussion for decades certainly, about what the role of the firm is, what’s the purpose of the firm? So, I would’ve just ask you what do you see as the purpose of the firm? And in that, what’s the role of the CEO?

HUBERY JOLY: Yeah, and of course we all remember on September 13th, 1970, a certain Milton Friedman wrote this very impactful article about the role of the firm. And he forcefully said, very forcefully, and of course there was a context around this, but that the sole purpose of the company was to maximize shareholder value. And in fact, he introduced a hiatus in the history of capitalism because before Milton Friedman, going back to the 19th century, companies had engaged on societal matters. They felt that they had a bigger role to play and that they were there to serve the common good and take care of different stakeholders, starting with their employees, but also the community. And so, for a while all of us were educated, right? Including at this wonderful school about … I remember when I was at McKinsey, this was what we were working on, optimizing performance. Now, we of course know that this is not valid, and I’ll take a very concrete example from my personal life. In May of 2020 when George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis and I was still at Best Buy at the time, which is headquartered in Minneapolis. Of course, the city was on fire. When the city is on fire, you cannot open your stores.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah.

HUBERY JOLY: Right? To quote a colleague, Rebecca Henderson, who wrote about this, “If the planet is on fire, you don’t have a business.” So, I think what we need is a declaration of interdependence and then go back to some principles around at the minimum as firms, we need a license to operate and we need to serve the common good over time. And it’s also the opportunity to address some of the most pressing issues in the world. So, I’m a big believer to my opinion today, shared by many, that the purpose of the firm is to do something good in the world and you can do well by doing good.

BRIAN KENNY: So, if the purpose of the firm has changed over time and evolved in the way that you described, then clearly the role of the CEO has also changed and evolved. What has changed in the world to drive that?

HUBERY JOLY: It’s changing expectations, right? And Edelman has published some statistics recently. Roughly speaking about two thirds of employees expect companies to play a role on societal matters. Two thirds of customers expect and prefer to deal with companies that they can connect with. And about 90% of investors take into account environmental matters and societal matters not for political reasons, it’s because these factors have an impact on business. As an example, if you’re an insurance company, Brian, do you think that climate change is going to have an impact on your loss ratio?

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. Of course.

HUBERY JOLY: Of course it will be. And if we have a society where more and more people are excluded and don’t have the opportunity to get insurance. At the end of the day, maybe just you and I are going to be insured, which is not going to be a good way to diversify risk. We’ve written a case about a French insurance company, AXA, on this matter, and they’ve had to lead a re-foundation of their business around some of these trends.

BRIAN KENNY: Mm-hmm. When you were CEO of Best Buy, I’m wondering if there were issues that you felt were important to wade in on? And I would ask that in the context of you as the CEO of the firm or you personally, HUBERY JOLY, were there things that you thought were important to take a position on?

HUBERY JOLY: It’s an important distinction because … And for the most part, I think that’s why the CEO in many cases may be the spokesperson. He or she is going to speak on behalf of the firm. So, we’ll go back to this because I think there’s some major learning from looking at these cases is that you need a set of criteria, you need a process, you need capabilities to be able to decide when and how to engage. It cannot be just left in general to just the CEO. But to answer your question, at Best Buy back in 2012, in fact, I was still the CEO of Carlson Companies, another great Minnesota company. An issue in the state was that there was going to be a referendum on whether or not to include in the state constitution the fact that a marriage was between people from two different sexes. And we had to decide … And this was the first time I had to wrestle with this and my wrestling was, “Gee, this can be a religious matter, can be a very personal matter. To what extent as a company do we have the moral authority to weigh in on this?” Right? And we discussed it at the board, and in the end, a number of us took personal positions in the state on that, but not a position as a company. Later on, I changed my perspective and I said, “No, there’s also a company matter, which is that we need to take care of our employees and we need to make sure that our great state is attractive to talent.” So, you see how my thinking evolved in the perspective. Later on at Best Buy, we had to deal with, and it’s again, very current today about the Dreamers. And we joined a coalition of companies that expressed our views that these Dreamers, they were here through no fault of their own and who were contributing to the economy, they were students, they were workers, we had many Dreamers as employees of Best Buy, should be protected. And acting as a group was helpful. Then later on we had to deal with the question of the tension with China. As you remember, President Trump was introducing increasingly high tariffs with China. So, we actually worked with his administration and him on trying to educate him on the impact that this could have. And then of course, now I’m on boards of a number of companies and we deal with these matters of an increasing complexity. So yes, as a CEO, you just can’t ignore this stuff.

BRIAN KENNY: Got it. It’s like the last job I would want the way you’re describing it, but it also, I think it shows that firms can no longer operate in isolation. You exist in a context. You exist in a global supply chain. You have employees who are also people, who have lives, and they have positions on things. So, it’s a very, very complicated and difficult line to navigate, I guess. Is that fair to say?

HUBERY JOLY: Complicated. Which is why I think ahead of any crisis, and we’ve seen, and I’ve encouraged companies to do this, and leaders, we need to develop a framework for deciding how and when to engage. At the highest level, how does it fit with your purpose as a company? How does it fit with your values? And how does it impact your stakeholders? Right? So, these are important criteria. So, to take examples of applying this. If you’re Microsoft, gun control is not going to be really an issue for you, you’re not involved in selling guns or you don’t really have a say on this, you’re not particularly competent or legitimate on this matter. But immigration is going to be a big deal because a lot of your workers, including your CEO, are immigrants and it’s essential to your business. In contrast, Walmart, so Doug McMillon there, guns is a big deal. He sells guns. He’s had stores and employees attacked on a number of occasions with guns. And so, this is something that he may decide to get involved in. And so the first thing is, what is your set of criteria? And then within your firm, what is the process? Who are you going to engage? Who are you going to consult? If something happened, what are the resources, internal or external resources? You probably need to build external capabilities as well. Because Brian, and the case illustrates this, the range of topics that you may want to and have to engage in is incredibly broad, right? From the Uyghurs in China to abortion, to voting rights and immigration. And there’s no way as a CEO, you can be competent on all these matters. And you have to understand the options you have, the implications. How are you going to get engaged? Are you going to say something? Are you going to do something? Are you going to be doing this in isolation, just on your own, or as a member of a coalition or through maybe industry groups? These are all important choices. And usually you don’t have that much time to react.

BRIAN KENNY: Right, of course not.

HUBERY JOLY: So, you’ve got to be prepared.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. Yeah. Is there an option to just do nothing? Is that one of the options that’s on the table?

HUBERY JOLY: Certainly not. At least it’s very risky. Bob Chapek, when he became CEO of Disney, declared that unlike his predecessor, Bob Iger, he would stay away from these issues. That’s not really the business that Disney is in. But of course, when the so-called Don’t Say Gay bill was introduced in Florida, after he decided to say nothing, a lot of his employees, including also of course, one of the heirs of the Disney family, revolted and put pressure on him. So, then he was on the back foot. So, saying nothing can be very dangerous. Your employees, a key responsibility as leaders we have is those who are in our care and about these societal matters, we have to be careful. We’re not elected officials. We’re not competent necessarily on all of these matters, but we do have our employees, and that’s the first place to think about when they’re under attack or it’s an issue that they care about.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. Yeah. I also thought it was interesting, the case highlighted a couple of situations involving Starbucks. The first being that they had taken a stance on diversity by encouraging their employees to write a particular sentiment on the cups. They’re famous for writing things on the cups. And that had mixed reactions from people. A few years later, they had a situation in one of their stores where there was an incident that certainly seemed to be racially motivated, where two African-American men were sitting and they hadn’t ordered anything, people might remember this, and the employee asked them to leave. And it really blew up into just a huge deal for Starbucks where they had to retrain the entire company. So, that to me is a great illustration of careful what stance you take, and then when you take it, make sure that your community, your firm, your employees are along for the ride with you and understand what you’re doing.

HUBERY JOLY: It’s such an important point, Brian, because in the criteria about when and how to engage, we talked about relevancy, your purpose, your values, your stakeholders, but another criteria is authenticity. One of the things I learned from my mother, I don’t know your mother, but my mother told me, “Son, before you criticize others, look inside, look inward.” Right?

BRIAN KENNY: She didn’t say it so kindly to me, but yeah, she had the same sentiment.

HUBERY JOLY: Yeah. Right. And so, another case that we have at the school is about Nike and the Colin Kaepernick case, and of course Nike, when Colin Kaepernick was taking the knee, supported their Black African-American athletes because they’re part of the family. That’s how in many ways, Nike has grown. But then it backfired, notably because it was then realized that internally Nike was not such a diverse organization. And so for me, in this increasingly volatile, divisive environment, one of the reflections in the classroom can be, revisit the balance between saying something and doing something and revisiting the balance between looking outside and looking inside. I think that the first priority should be doing something inside, so that you take care of those in your care before you teach lessons. On the other end there’s cases where it’s actually relevant and appropriate and effective to speak up. And you have to think about the leverage you have and the risk you take from that standpoint.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. I was going to ask you about that. What’s the political calculation that a CEO has to go through when they’re deciding whether or not to weigh in on something? And who do they have to check with? I mean, do they have to go to the board? Is it something that they really have to … Because you said time is of the essence here.

HUBERY JOLY: Yeah. So, many questions here. So, having an internal process and as the CEO people you can go to, I know that Jeff Harmening, the CEO of General Mills, we have another case on this, following George Floyd, because of course General Mills is headquartered in Minneapolis, the first people he called were some of his Black executives and the Black employee resource group, to check in with them and see how they felt and then what advice they might have on this. So, that’s an important consideration. Now, Ken Frazier, following the incident in Charlottesville, where, as you may remember, following demonstrations, the president said that there was good people on both sides, including white supremacists and the other side. And Ken Frazier, the CEO of Merck, who is African-American and who was at the time with many other CEOs in one of the president’s advisory council, decided to step down from that council and spoke up. He had the support of his board, but he didn’t take much time. He felt that this was such an important issue to the values of his company, that they had to engage. A number of criteria to shed some light on this. First, you always have to stay true to your values, right? In these difficult moments, staying true to your true north, your values, which is what Ken Frazier did, but also looking at your leverage and the risks you’re taking. So, if you’re a consumer brand like Bud Light or Target, the risk of retaliation is higher than if you’re a B2B business. So, JPMorgan, Jamie Dimon, who’s the godfather of capitalism in this country, following some hate crimes against Asian individuals, really spoke up and spoke his mind against racism. And, so many people look up to Jamie and it’s harder to retaliate against JPMorgan than compared to orchestrating a boycott of Bud Light. So, these are considerations to take into account as well.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. Much of the backlash against CEOs who take positions on these things seems politically motivated. I think that’s probably a classic understatement. Does a CEO need to explain to that group why they’re doing this? Or do you just ignore that and say, “You know what? We’re taking a position. Here’s why we’re doing it and we feel good about it.”?

HUBERY JOLY: So, first communication priority, you head communication, Brian, for this great institution, is internal.

HUBERY JOLY: So, last year we had Roe v. Wade being overturned. And by the way, is that a subject on which companies should take a public stance? This is the highest court in the lands that has decided. What impact is it going to have? What good is it going to do? But certainly, having a conversation with your employees. And by the way, another lesson is, don’t wait. Be proactive in ahead of time identifying the issues that are likely to be on the horizon and impact your company and start planning for this. Don’t wait, otherwise you’re going to be on the back foot. But many companies, because of this planning had already introduced provisions in their healthcare plans to enable employees to travel across state lines to get healthcare, which was a way to assist their employees. But then internally have a conversation. And by the way, have a conversation with a diversity of your employees, because who says that the 125,000 employees of Best Buy are just from one camp, right? We have employees in all states, all walks in life. One of the new employee resource groups you should probably create that did not exist historically, is conservatives. And they’re an equally valuable member of the organization and engage them in the dialogue and try to listen. One of the great attributes of great CEOs these days is they have two ears and one mouth, and they should start by listening. And of course, listening to their heart, but also listening to those around them, listening to those who are competent on these matters. And try to do their best. And again, that means oftentimes being guided by their values and what they believe is the right thing to do.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. We know that, you mentioned earlier in our discussion, that the majority of people expect CEOs to take a position on some of these issues. I think we also know that the millennials they care a lot about the companies that they buy products from, and they really care about the companies that they work for, and they want those companies to stand for something. So, I’m just wondering, as a CEO, is this something that you look at as a brand enhancing choice that you make to affirm for your employees that we do stand for something?

HUBERY JOLY: And that’s why you need it to be authentic. And you and I have talked about this before, Brian, that’s where purpose comes to the forefront. What is the good you’re trying to create in the world and what are your key values? And if you’re centered around that, and of course, if the strategy and performance is derived from that, right? So, it cannot be made up and separate from the business. Then it makes a big difference because then it’s going to be authentic. So, at Best Buy, our purpose is to enrich lives through technology by addressing key human needs. And it’s a very human culture. At Ralph Lauren where I’m on the board, it’s to inspire the dream of a better life through authenticity and timeless style. And of course, one implication of that is that, of course you’re going to have a diverse organization, inclusive organization, where everybody can feel they belong. And then when something happens, you know what your true north is. So, Corie Barry, who was the CEO of Best Buy, my successor, when George Floyd was murdered, her reaction to this was, “We can do better.” Right? And we had been engaged at Best Buy for a number of years on trying to enhance our environment and create a more inclusive environment, more diverse environment. We’ve made great progress. But her sense was, “We can do better.” And that started with, what to do at Best Buy and that started also, what kind of coalition can be mounted at the state level? Because in the great state of Minnesota, and from my accent, you can tell that’s where I’m from, there’s a number of great companies and working with the governor, you can try to make a difference here. But if you’re guided by purpose and values, then good things happen.

BRIAN KENNY: We’ve seen recently, really within the last year, I would say, a backlash against ESG, environmental, sustainability, and governance, which is something that we talk a lot about at Harvard Business School. There’s a lot of cases, we’ve had them on Cold Call, about firms and investment companies that are focused on ESG, and now all of a sudden there seems to be this pushback against that. And it’s this, I think the chorus that we’re hearing is, business should be focused on business and not social issues. What would you say to somebody who throws that at you?

HUBERY JOLY: So, a number of words and concepts have become toxic and weaponized.

HUBERY JOLY: ESG is one of these. DE&I is another one. I learned from a great colleague, Francis Frei, that once a concept or a vocabulary is weaponized, you stop using it, but you continue to do what’s right. So, is incorporating external factors from all of your stakeholders, important to develop a strategy? Yes, yes, yes. And that includes, of course, your employees, your customers, your vendors, the communities in which you operate, and the planet. And of course, you need to take this into account to generate great economic performance over time. And again, if the planet is on fire, you’re not going to have a business. So, if you’re an apparel company like Ralph Lauren, taking care of the factories in Asia and what happens there, we all remember, Ralph Lauren was not at all involved in that, but the fire in a number of plants or factories in Bangladesh a few years ago. They’re not owned by Target or Ralph Lauren or Levi Strauss, these factories, but we source from them. So, making sure that you look at that there’s no child labor, that there’s safety and good working conditions in these factories. First, it’s the right moral thing to do, but also the consumers are going to go after your throat if you don’t take care of that. So again, ignore these factors at your great peril.

BRIAN KENNY: Hubert, this has been a great conversation as I expected it would be. And I usually end by asking my guests if there’s one thing you want people to remember about the case, what would it be? I’m going to ask that a little bit differently to you today, and that is, if you were sitting down with a friend who was looking at a CEO position and they were equivocating about, “Should I take this job, should I not?” What advice would you give them?

HUBERY JOLY: Well, I would say this is an increasingly challenging world, so don’t expect the job to be fun every day.

HUBERY JOLY: At the same time, if your inner purpose is to make a difference in the world, right? It’s not about power, fame, glory or money. If it’s something about making a difference in the world, companies now have the opportunity and the duty to make a big difference in the world and can contribute to solving some of our most pressing issues in the world. And I think 10 years from now, 20 years from now, maybe you’ll look at this time and you’ll say, “This was our finest hour.” And so, a lot of the conversation with CEOs and aspiring CEOs is that this can be great leadership moments, and if you’re interested in pursuing that, better take care of yourself, right? Because in order to take care of others … Remember, when we’re flying, we’re told, “If the oxygen masks come down, put them on yourself first before you help others.”

HUBERY JOLY: So, you’re going to need to take care of yourself so that you have the inner strengths and the moral compass, and then the network around you to help you do a job that’s increasingly difficult, clearly, Brian, for sure.

BRIAN KENNY: That is great advice from somebody who’s been there. Hubery Joly, thank you for joining me on Cold Call .

HUBERY JOLY: Thank you, Brian.

BRIAN KENNY: If you enjoy Cold Call , you might like our other podcasts, After Hours , Climate Rising , Deep Purpose , IdeaCast , Managing the Future of Work , Skydeck , and Women at Work . Find them on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen, and if you could take a minute to rate and review us, we’d be grateful. If you have any suggestions or just want to say hello, we want to hear from you. Email us at [email protected] . Thanks again for joining us. I’m your host, Brian Kenny, and you’ve been listening to Cold Call , an official podcast of Harvard Business School and part of the HBR Podcast Network.

- Subscribe On:

Latest in this series

This article is about business ethics.

- Climate change

- Corporate social responsibility

- Social movements

Partner Center

Rethinking how companies address social issues: McKinsey Global Survey results

The vast majority of companies, according to the results of a recent McKinsey survey, 1 1. The online survey was in the field from May 21, 2009, to June 3, 2009, and received responses from 2,245 senior executives from around the world, representing the full range of functional specialties and industries except health care. believe that economic growth in developing markets is important to the success of their business strategies. And more than two-thirds of those companies are engaged in various programs to encourage that growth, whether through education or private-sector development or technological advancement.

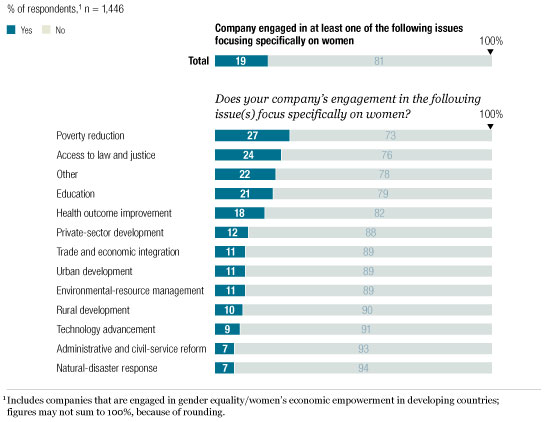

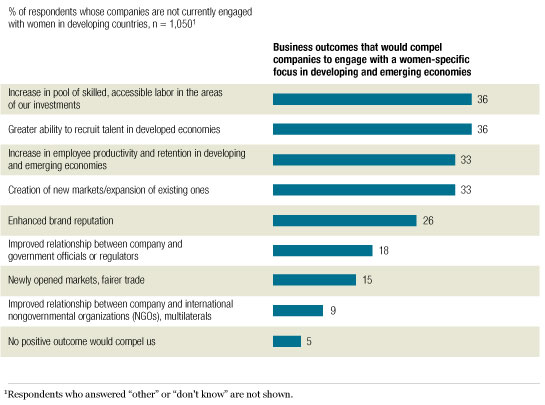

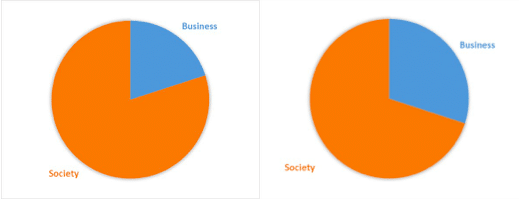

But many of these programs may be less effective than they could be, the survey results suggest. That’s because only 19 percent of respondents say their companies’ development programs focus on women, even though a great deal of recent research by the World Bank, the United Nations, and academic scholars indicates that programs focused on women generate better outcomes, in terms of specific program goals and overall development objectives. For instance, an extra year of secondary schooling has been demonstrated to increase women’s future wages by 10 to 20 percent, significantly higher than the 5 to 15 percent return observed among men. 2 2. George Psacharopoulos and Harry Anthony Patrinos, “Returns to investment in education: A further update,” Education Economics , 2004, Volume 12, Number 2, pp. 111–34. It is important to note that underlying wage gaps between men and women have been factored out of this analysis. In addition, women who earn income are especially powerful catalysts of development because they reinvest a larger portion of their income in the health, education, and well-being of their families, compared to men. 3 3. Phil Borges, Women Empowered: Inspiring Change in the Emerging World , New York: Rizzoli, 2007, p. 13. It is important to note that underlying wage gaps between men and women have been factored out of this analysis.

The survey asked senior executives from companies headquartered around the world if and how their companies operate in developing markets, whether they are addressing social issues tied to economic development, and whether any of their development programs focus on women. The survey also asked about whether and how focusing on women has affected profits at these companies and, for companies not focused on women, what might cause them to do so.

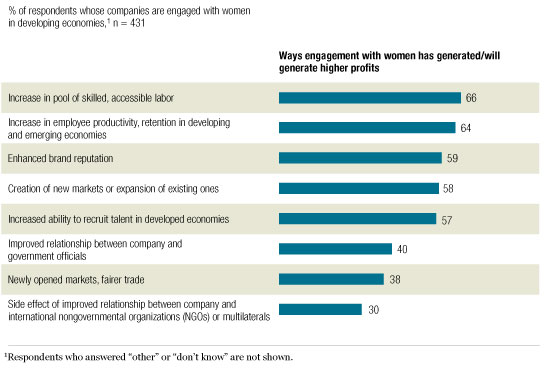

It is particularly notable that most respondents to this survey whose companies focus their development programs on women say the focus has boosted profits or will do so soon. This is surprising because, in general, companies have great difficulty making financial assessments of the corporate benefits of social investments. Respondents’ ability to see a clear link to profits likely results from a combination of the issues companies are addressing (particularly education), the targets of their programs (most often current and future employees), and the multiplier effect of focusing on women.

How companies are spurring development

Three-quarters of the companies represented in the survey are somehow active in developing markets, 4 4. In this article, we use the term developing markets to refer to developing and emerging economies. Those are defined by the World Bank as countries classified as low or middle income that tend to have lower than average GDPs per capita, life expectancies, and literacy rates. most often by making sales in those countries and having offices there. And the vast majority say economic growth in those markets is now and will continue to be important to the success of their business strategies. So, for most companies, there are clear business reasons to support growth in developing countries. Indeed, the importance companies place on encouraging such growth is highlighted by the finding that, even during the past calendar year of economic crisis, most of the companies addressing issues in developing markets have at least maintained their previous levels of engagement, while 38 percent have increased it.

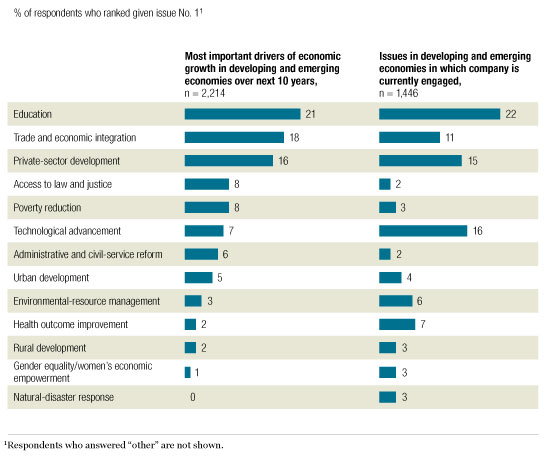

Survey respondents identify education, trade and economic integration, and private-sector development as the top drivers of economic growth in developing markets over the next ten years (Exhibit 1). These drivers overlap with the top three issues that companies are seeking to address in some way: education, technological advancement, and private-sector development. 5 5. “Addressing” an issue was defined as making corporate financial contributions or supporting employee donations or volunteerism, as well as other corporate initiatives or company policies.

Top drivers of economic growth

Focusing on women

Among executives at companies addressing one or more development issues, only 19 percent say their programs focus on women—that is, programs that specifically promote gender equality or women’s economic advancement or that make women the central focus of programs with other aims (Exhibit 2). Notably, in comparing responses from these companies with responses from companies that have not focused on women in their development programs, the same issues—education, trade and economic integration, and private-sector development—are seen as important and are most frequently addressed. What’s different is just the choice of a women-specific angle.

It must be noted that addressing these issues—even without a focus on women—often helps women’s economic position significantly. However, programs that focus specifically on women create more benefit for women and society as a whole, according to many studies over the past 15 years. Countries that have not achieved gender parity in education, for example, have been found to forgo 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points annually in per capita economic growth. 6 6. Dina Abu-Ghaida and Stephan Klasen, “The costs of missing the Millennium Development Goal on gender equity,” World Development , 2004, Volume 32, Number 7, pp. 1057–1107. Further, a one-year increase in schooling of all adult females in a country is correlated with an increase in GDP per capita of roughly $700 and a 0.7 percent increase in the participation of women in the formal labor force. 7 7. World Bank, “Focus on women and development: Improving women’s health and girls’ education are key to reducing poverty,” worldbank.org, March 8, 2004. Compounding these effects is the fact that educated and employed mothers have a stronger positive influence on the health and educational outcomes of their children than do similar fathers.

Where the focus is on women

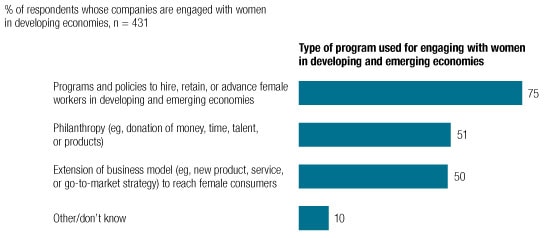

At the companies focused on women’s development, the most common reason for that decision is that the focus is consistent with company culture or tradition. These companies’ programs most often target current and future employees, closely followed by women in society at large. Consistent with a focus on employees, three-quarters of respondents describe their efforts as programs and policies to hire, retain, or advance female workers in developing economies (Exhibit 3).

How companies engage with women’s development

Missing a chance for higher profit?

Among respondents whose companies are engaged with women on development issues, 34 percent say the engagement has already increased profits, and another 38 percent expect it to do so, most often by increasing the pool of skilled and accessible labor (Exhibit 4). Given how hard it can be for companies to assess the financial benefits they can gain from social programs, this finding is initially startling. However, it is less so considering the research measuring benefits from programs that focus on women and the fact that many respondents’ programs focus on education and generally target current and potential employees. Notably, executives at companies with programs that don’t focus on women say the same labor force benefits already reported by others would encourage them to adopt such programs (Exhibit 5).

So why do relatively few focus on women? One reason is that many companies don’t know that such a focus can increase the social impact of many programs. Two-thirds of respondents to this survey say that their companies have been unaware of the research or that they don’t know whether the company is aware of it. Furthermore, respondents at more than half of these companies say they have never considered focusing on women as a distinct strategic or philanthropic priority.

Profits from women

Compelling reasons

Beyond that, companies are typically aware that addressing social issues can create hard business benefits beyond maintaining or improving reputation—particularly in improving employee morale and retention. 8 8. For example, see “ The state of corporate philanthropy: A McKinsey Global Survey ,” mckinseyquarterly.com, February 2008. However, these effects can be hard to measure and often aren’t considered when assessing social programs. For example, in a McKinsey survey from January 2009, 9 9. “ Valuing corporate social responsibility: McKinsey Global Survey Results ,” mckinseyquarterly.com, February 2009. three-quarters of CFOs and investment professionals said social programs make positive long-term contributions to shareholder value, but only 37 percent said that’s true in the short term. For the most part, respondents to that survey said value comes from maintaining a good corporate reputation broadly, and most respondents were unable to fully integrate the effects of social, environmental, or governance programs into financial analyses. In common with those findings, 35 percent of respondents to this survey say they would most likely focus development programs on women if such a focus would generate additional value or improve corporate performance, while nearly half say they would do so in response to internal or external pressure of other kinds (Exhibit 6).

As long as these attitudes persist, both the potential to create short-term financial benefits from social investment and the multiplier effect of focusing on women are unlikely to occur to most companies.

Money motivates—sometimes

Looking ahead

If they do not already do so, companies can likely make many programs—such as those in education—more effective for communities and themselves simply by incorporating a focuson women.

Companies appear to see investing in education as a way to address many social issues; thefact that doing so also builds a larger, more qualified labor force is a clear additional benefit.

Contributors to the development and analysis of this survey include Kameron Kordestani, a consultant in McKinsey’s New Jersey office, and Irina A. Nikolic and Lynn Taliento, an associate principal and a principal, respectively, in the Washington, DC, office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Centered leadership: How talented women thrive

Valuing corporate social responsibility

How helping women helps business

These Entrepreneurs Take a Pragmatic Approach to Solving Social Problems

In 1908, Harvard Business School’s first dean, Edwin Francis Gay, welcomed the School’s inaugural class of 59 students by saying that HBS was challenged with encouraging its students to have the “intellectual respect for business as a profession, with the social implications and heightened sense of responsibility which goes with that.”

The purpose of business, Gay said, was to make “a decent profit decently.”

In the 111 years since then, many HBS alumni have taken the school’s emphasis on social responsibility to heart by attempting to effect societal change. A recent book, Problem Solving: HBS Alumni Making a Difference in the World —co-authored by HBS Professor Emeritus Howard Stevenson, HBS project director Shirley Spence, and writer Russ Banham—shares more than 200 stories of HBS graduates who have taken steps toward tackling social challenges. For example:

- As CEO of Curriculum Associates, Robert Waldron turned a company that was in decline in 2008 into a profitable $190-million business 10 years later by developing online learning tools as well as print workbooks for schools. In 2017, the company gifted the majority of its shares, valued at $200 million, to charity.

- Diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a rare and incurable blood cancer, Kathy Giusti cofounded the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, which has helped thousands of other patients with the cancer and has accelerated drug discovery and development for several other diseases.

- Sir Ronald Cohen left a successful career in venture capital private equity to launch a global movement that has brought together governments with service providers and has attracted private investment to pay for a variety of social programs. One such program in 2010 reached out to help 2,000 young criminal offenders who were released from a UK prison, significantly reducing the rate of recidivism.

The book is the result of four years of research, including a survey of 13 MBA classes, more than 200 interviews, and extensive archival and secondary research.

Stevenson says the research team found that alumni tend to take a pragmatic approach to figuring out their own best ways to contribute.

“Our people feel a moral imperative to act, but they don’t go out and try to solve world hunger,” he says. “They identify a problem where they think their skills and resources can make a difference, and they dive in with an optimism that they can do it, rallying others to their cause as they go.”

Dina Gerdeman: We talk about corporate social responsibility (CSR) today, yet it’s clear from the book that this emphasis on business solving social problems isn’t new. Do you think readers might be surprised to learn that these efforts date so far back?

Howard Stevenson: I think it depends on your perspective. The discussion about the role of business in society and the responsibilities of business leaders has been going on since Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776. CSR is a relatively new movement espousing a triple bottom line of people, planet, and profits, rather than a single-minded focus on shareholder value. People of my vintage recall when business leadership was about serving customers at a profit and giving back to your community was expected. And many of today’s business students arrive with a commitment to social impact through or alongside their professional careers.

Shirley Spence: While our book primarily focuses on the social impact of today’s business graduates, we wanted to point out that this is not a new phenomenon. HBS and its alumni have been responding to the challenges and opportunities of their times for more than 200 years, from the economic boom and social challenges of industrialization to what has been described as the promise, peril, and unrealized potential of the 21st century. The language and methods have evolved and continue to evolve, but the strong sense of social responsibility remains a constant.

Gerdeman: Do you think the case method of teaching helps prepare business school students to consider how they might be able to contribute to society?

Stevenson: The case method by definition is about problem solving, regardless of the nature of the problem. Basically, you are teaching people to ask the right questions, sort through too much information, define the problem, identify options, and hone in on a solution from the vantage point of a particular person in a particular situation. It’s pretty easy to say that some problems are unsolvable, but we don’t let students get away with that in class. We ask: What can you do about it with the resources you have or can rally to your cause?

I think that one of the things the case method does for people is to say, it’s possible. It gives them a sense of confidence. As one interviewee put it, “HBS gave me a deep-rooted sense of optimism. Against the backdrop of all the problems in the world, it’s about focusing on solutions and the belief that we can make meaningful change.” Our research found business people tackling education, health, environment, poverty, inequality, and other challenges in every corner of the world.

Gerdeman: Were there any big surprises from your research?

Stevenson: I first arrived at Soldiers Field as an MBA student in 1963, stayed to do my doctoral work, and spent 40 years as an HBS professor and senior administrator. Over that time, I met thousands of students and alumni. I knew that many were applying their skills and resources for social good, but I was amazed—and inspired—by the breadth and depth of activity that our research uncovered and the passion that people bring to their social impact work.

Each story is unique, but problem solving was a common theme and we were able to detect some patterns. There basically is an infinite combination of five core strategies being used across a spectrum of impact to make positive change. The strategies include finance for social purpose, capacity building, product and market innovations, social and political mobilization, and government policy and legislation. Any and all of those strategies can be used to fulfill urgent needs, address the root causes of problems, and strive for system-wide change.

Spence: Our research also looked at how social impact journeys evolve over the course of a person’s lifetime. Causes of interest and alumni’s approaches for addressing problems and opportunities will change, in sometimes predictable and sometimes serendipitous ways. And, at any given time and especially over time, people may wear multiple hats as corporate leaders, entrepreneurs, investors, nonprofit professionals, public servants, philanthropists, and volunteers contributing at local, national, and international levels.

Gerdeman: The early 2000s were a rocky time for business, with the global financial crisis and people like Bernie Madoff jailed for fraud. Was there a sense during this time that business schools weren’t doing their job in terms of graduating ethical business leaders?

Stevenson: What I would say was there was a sense that ethics were forgotten as investor capitalism became the new business model, with shareholder value and personal gain at its core. It sparked considerable soul searching at business schools and discussion of whether and how ethics can be taught. Here, too, I think that the case method can help. As a professor, you can inject ethical questions into the discussion of any case problem, raising moral issues and asking students to consider the social and environmental impact of the solutions they are proposing.

Many schools have made programmatic and other changes geared to heightening students’ awareness of corporate and personal accountability. At HBS, I actually think that—as with many developments—it is the students who are driving ethics back to the forefront again. I think they are saying no, that’s not what leadership is about, and that’s not what I want to be.

Spence: There are many examples of student efforts to promote social action and ethical behavior. The student-run Social Enterprise Conference draws over 1,000 participants each year. One group of students successfully lobbied faculty to create a field-based course on poverty and inequality. Members of one graduating class crafted and signed an MBA Oath with a professional code of ethics. Another class launched a Commit to Start initiative to encourage new graduates to take concrete steps to immediately get involved in their communities.

Gerdeman: Given the perception by many in the public that businesses are concerned only with making profits, are you hoping this research will open people’s eyes to the fact that many business leaders actually are championing social causes?

Spence: We know that there’s a keen interest among HBS alumni to know what other alumni are doing to advance social causes. We hope that Problem Solving will meet that need and provide role models for students. It’s also intended to be a reminder to the faculty and staff and everyone else in the HBS community of the true meaning of the School’s mission to educate leaders who make a difference in the world.

Stevenson: There’s no avoiding the negative press that business people get daily, sometimes deservedly, which often overshadows the many more positive examples of CEO activists and business people quietly working to better society. The book’s stories—which effectively are mini case studies—shine a spotlight on the latter. I hope our research will cause people to say, “I didn’t know business leaders were doing these kinds of things.: And inspire both academics and business people to say, “I can do something, too. Now, what should I do?”

BOOK EXCERPT

Healthy and sustainable food.

Around the world, HBS alumni are tackling the challenges of food insecurity and realizing the potential of sustainable agriculture.

Ndidi Okonkwo Nwuneli (MBA 1999), Mezuo Nwuneli (MBA 2003) and Kola Masha (MBA 2006) are working to unlock the potential of agriculture in West Africa. The Nwunelis—a husband and wife team—co-founded AACE Food Processing & Distribution Ltd. in 2009 to combat malnutrition, provide jobs, and reduce Nigeria’s need for costly food imports. AACE Foods processes, packages, and distributes branded food products sourced from subsistence farmers. “Our vision is to be the preferred provider of food to West Africans,” they said.

In 2010, the Nwunelis founded Sahel Capital, which includes a consulting business and a private equity venture. The consulting arm provides crop value chain analysis, strategic consulting, public policy development, and implementation support for partners across West Africa. The private equity venture manages the $66-million Fund for Agricultural Finance (FAFIN) in Nigeria, which invests in small- and medium-sized agricultural ventures. “In Nigeria and across West Africa, there are tremendous opportunities to transform the agricultural landscape,” the Nwunelis said.

Kola Masha (MBA 2006) sees smallholder agriculture as the key to tackling poverty and preventing the spread of insurgency among unemployed youth in Nigeria. Through his impact investing firm, Doreo Partners, he founded Babban Gona, which means “great farm” in Hausa, as a for-profit social enterprise.

“Low economies of scale keep smallholder farmers in a cycle of poverty,” Masha explained. Babban Gona uses an agricultural franchise model inspired by Masha’s grandfather, a South Dakota farmer. “Growing up in Lagos, I remember my mother talking about how her father struggled to earn a living—until he joined a farmers’ cooperative,” he said.

Babban Gona recruits groups of enterprising farmers and provides them with affordable credit, agricultural inputs, training, and marketing services. “Since 2010, we have more than doubled the yields and incomes of tens of thousands of smallholders and are on track to serve 1 million farmers by 2025,” Masha reported.

Babban Gona specifically attracts rural youth who are otherwise driven to urban centers’ promising jobs, only to struggle and become vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups. “Everyone deserves a secure future,” Masha said. “To end insecurity, we must unlock the potential of agriculture as a job creation engine for millions of youth.”

Andrew Kendall (MBA 1988) is on a mission to change the way New England eats. As executive director of the Henry P. Kendall Foundation, his family’s philanthropic organization, Kendall is dedicated to increasing the production and consumption of local, sustainably produced food.