- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Finding Market Exchange Rates

Reading an exchange rate, conversion spreads, calculate your requirements, the bottom line.

- Guide to Forex Trading

- Strategy & Education

How to Calculate an Exchange Rate

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/cory1__cory_mitchell-5bfc262946e0fb005118b3b7.jpg)

Yarilet Perez is an experienced multimedia journalist and fact-checker with a Master of Science in Journalism. She has worked in multiple cities covering breaking news, politics, education, and more. Her expertise is in personal finance and investing, and real estate.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YariletPerez-d2289cb01c3c4f2aabf79ce6057e5078.jpg)

An exchange rate is how much it costs to exchange one currency for another. Exchange rates fluctuate constantly throughout the week as currencies are actively traded. This pushes the price up and down, similar to other assets such as gold or stocks.

The market price of a currency—how many U.S. dollars it takes to buy a Canadian dollar for example—is different than the rate you will receive from your bank when you exchange currency. It is often a key element of financial trilemmas .

Here's how exchange rates work, and how to figure out if you are getting a good deal.

Key Takeaways

- An exchange rate determines the cost to buy one currency with another.

- The forex market price is different from the rate you receive when buying a foreign currency at your bank.

- Your bank marks up the market price as compensation for its currency exchange service.

- You can shop around for the most attractive exchange rate available.

- Currency exchange rates change throughout the day.

Traders and institutions buy and sell currencies 24 hours a day during the week . For a trade to occur, one currency must be exchanged for another. To buy British Pounds ( GBP ), another currency must be used to buy it. Whatever currency is used will create a currency pair . If U.S. dollars ( USD ) are used to buy GBP , the exchange rate is for the GBP/USD pair. Access to these forex (foreign exchange) markets can be found through any of the major forex brokers .

If the USD/CAD currency pair is 1.33, that means it costs 1.33 Canadian dollars to get 1 U.S. dollar. In USD/CAD , the first currency listed (USD) always stands for one unit of that currency; the exchange rate shows how much of the second currency (CAD) is needed to purchase that one unit of the first (USD).

This rate tells you how much it costs to buy one U.S. dollar using Canadian dollars. To find out how much it costs to buy one Canadian dollar using U.S. dollars, use the following formula: 1/exchange rate:

1 / 1.33 = 0.7518

It costs 0.7518 U.S. dollars to buy one Canadian dollar. This price would be reflected by the CAD/USD pair. In this instance, the position of the currencies has switched.

Some of the most popular currencies that trade against the U.S. dollar are the Euro ( EUR/USD ), the Japanese Yen ( USD/JPY ), the British Pound ( GBP/USD ), the Swiss Franc ( USD/CHF ), the Australian Dollar ( USD/AUD ), the New Zealand Dollar ( USD/NZD ), and the Canadian dollar ( USD/CAD ).

The ordering in each set of parentheses for these exchange pairs reflects the customary direct quote scheme for each pairing.

When you go to the bank to convert currencies, you most likely won't get the market price that traders get. The bank or currency exchange house will markup the price so they make a profit. Credit cards and payment service providers such as PayPal will also do this when converting currencies.

If the USD/CAD price is 1.33, the market is saying it costs 1.33 Canadian dollars to buy 1 U.S. dollar. At the bank though, it may cost 1.37 Canadian dollars. The difference between the market exchange rate and the exchange rate they charge is the bank's profit. To calculate the percentage discrepancy, take the difference between the two exchange rates, and divide it by the market exchange rate:

((1.37 - 1.33)/1.33)*100 = 3% markup

A markup will also be present if converting U.S. dollars to Canadian dollars. If the CAD/USD exchange rate is 0.75 (see the section above), then the bank may charge 0.7725. They are charging you more U.S. dollars than the market rate:

((0.7725 - 0.75)/0.75)*100 = 3% markup

Banks and currency exchanges compensate themselves for this service. The bank gives you cash, whereas traders in the market do not deal in cash. In order to get cash, wire fees and processing or withdrawal fees would be applied to a forex account in case the investor needs the money physically.

In most cases, someone converting currencies wants to get the cash instantly and with as few fees as possible. Paying a markup to a bank or credit card company is a worthwhile compromise.

If you are converting one currency to another, shop around for an exchange rate that is closer to the market exchange rate; it can save you money. Some banks have ATM network alliances worldwide, offering customers a more favorable exchange rate when they withdraw funds from allied banks.

Need a foreign currency? Use exchange rates to determine how much foreign currency you want, and how much of your local currency you'll need to buy it.

If heading to Europe you'll need euros ( EUR ), and will need to check the EUR/USD exchange rate at your bank. The market rate may be 1.113, but an exchange might charge you 1.146 or more.

Assume you have $1,000 USD to buy Euros with. Divide $1,000 by 1.146 (what a bank may charge) to get 872.60 euros. That is how many Euros you get for your $1,000. Since Euros are more expensive, we know we have to divide, so that we end up with fewer units of EUR than units of USD.

Now assume you want 1,500 euros, and want to know what it costs in USD. Multiply 1,500 by 1.146 to get 1,719 USD. Since we know Euros are more expensive, one euro will cost more than one US dollar, that is why we multiply in this case.

Do You Multiply or Divide to Convert Currency?

To convert from a base currency, you would multiply by the exchange rate. If the exchange rate is greater than 1, you will get a larger number—that is, you will get more of the second currency in exchange for the first. If the exchange rate is smaller than one, you will get a smaller number, which means you get less of the second currency in exchange for the first.

Do Exchange Rates Stay the Same?

Currency exchange rates change multiple times a day based on how they are being traded, which is in turn impacted by the global economy. If there is a high demand for a certain currency, its value will increase.

What Is Forex?

Forex stands for foreign exchange . It is the market for trading international currencies. Similar to how stock traders buy and sell stocks based on how they expect the values to go up or down, forex traders exchange large amounts of one currency for another based on which they think will have the highest value due to global conditions.

Exchange rates always apply to the cost of one currency relative to another. The order in which the pair are listed matters. Remember the first currency is always equal to one unit and the second currency is how much of that second currency it takes to buy one unit of the first currency. From there you can calculate your conversion requirements.

Banks will markup the price of currencies to compensate themselves for the service. Shopping around may save you some money as some companies will have a smaller markup, relative to the market exchange rate, than others.

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). " Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign Exchange Turnover in April 2019 Monetary and Economic Department ," Pages 5 and 10.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/forex17-5bfc2b91c9e77c0026306532.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

One to one maths interventions built for KS4 success

Weekly online one to one GCSE maths revision lessons now available

In order to access this I need to be confident with:

This topic is relevant for:

Exchange Rates

Here we will learn about how to work out exchange rates, including how to convert between British pounds and foreign currencies and read conversion graphs.

There are also how to work out exchange rate worksheets based on Edexcel, AQA and OCR exam questions, along with further guidance on where to go next if you’re still stuck.

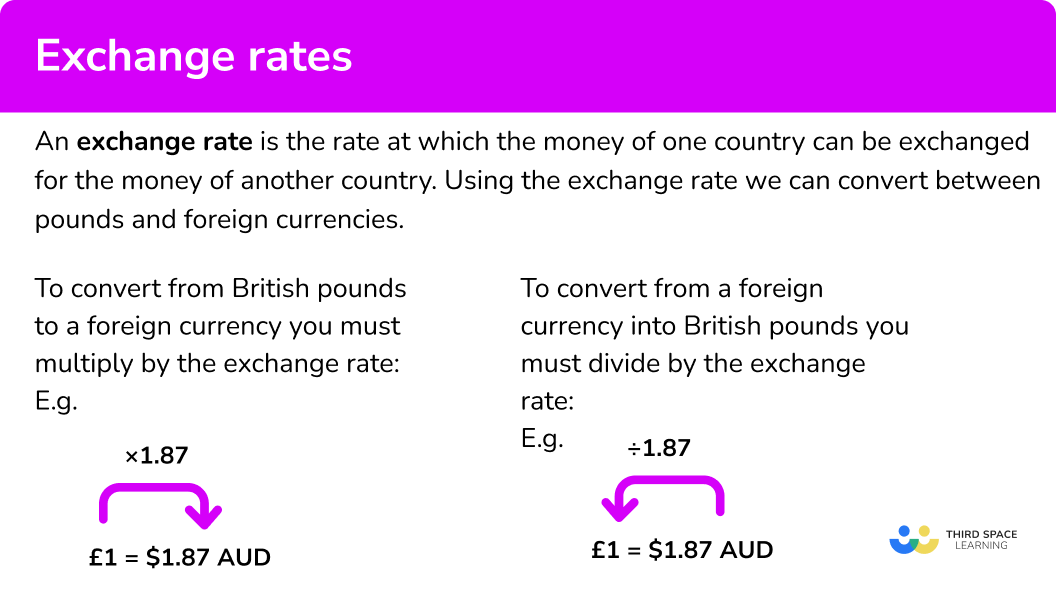

What is an exchange rate?

An exchange rate is the rate at which the money of one country can be exchanged for the money of another country. It can also be referred to as a foreign exchange rate and be seen as the price of one currency expressed in terms of another currency.

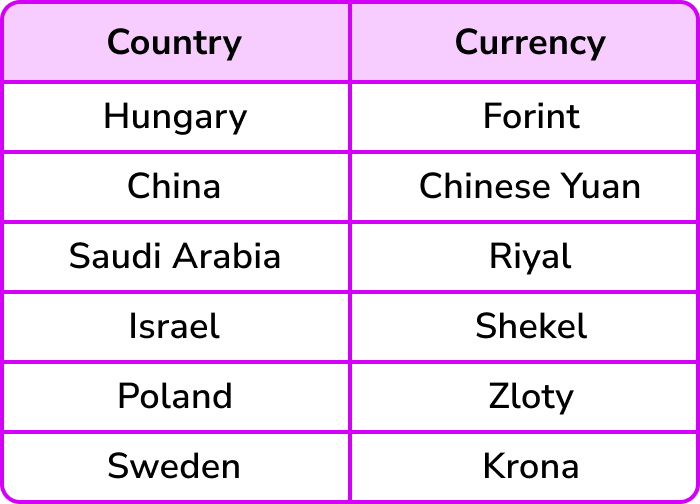

In the United Kingdom our currency is the British pound or pound sterling . The exchange rate tells us the value of £1 in terms of a foreign country’s currency. Different countries have different currencies.

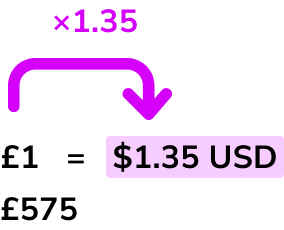

For example,

The exchange rates are constantly changing depending on the country’s economic status. It is the role of the central bank to monitor these fluctuations and adjust the country’s monetary policy accordingly.

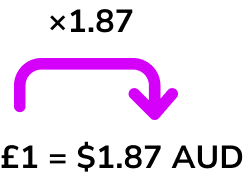

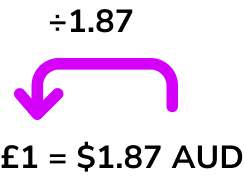

Using the exchange rate we can convert between pounds and foreign currencies. To do this we need to either multiply or divide the quantity we are trying to convert with the exchange rate.

To convert from British pounds to a foreign currency you must multiply by the exchange rate.

So £150 would be \$276 because 150 \times 1.87=276.

To convert from a foreign currency into British pounds you must divide by the exchange rate.

So, \$430 would be £229.95 because 430 \div 1.87=229.95 (to 2 dp).

A GCSE Mathematics question may ask you to convert between other currencies. It will normally give the exchange rate in a form similar to a 1:n ratio.

Dollars to Euros

To convert from the currency given as “1” we would multiply by the exchange rate.

To convert to the currency given as “1” we would divide by the exchange rate.

How to work out exchange rates

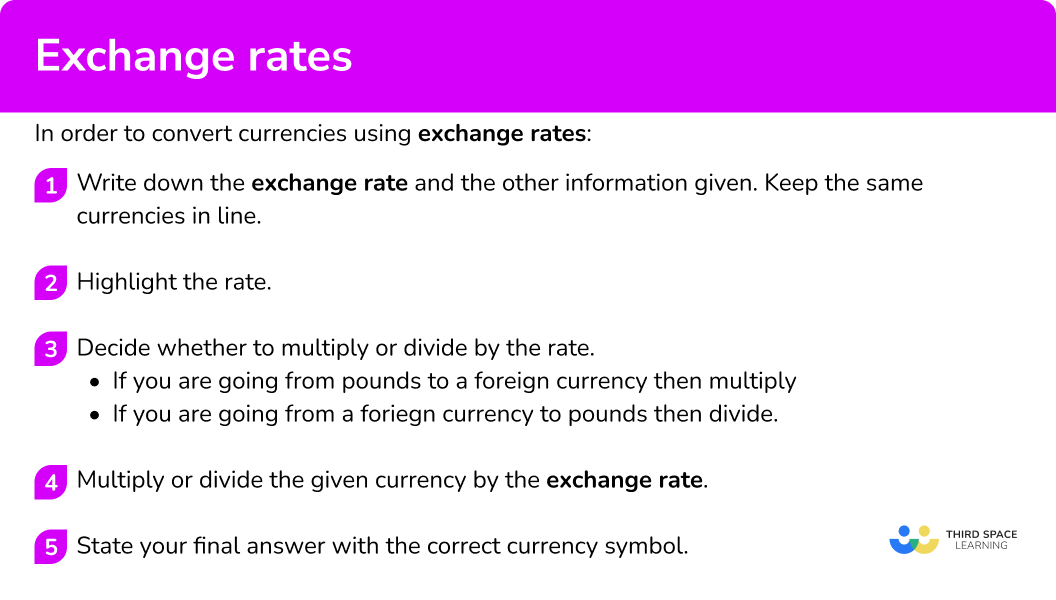

In order to convert currencies using exchange rates:

Write down the exchange rate and the other information given. Keep the same currencies in line.

Highlight the rate.

- Decide whether to multiply or divide by the rate . If you are going from the “1” to the other currency then multiply. If you are going to the “1” from the other currency then divide .

Multiply or divide the given currency by the exchange rate.

State your final answer with the correct currency symbol.

Explain how to work out exchange rates

How to work out exchange rates worksheet

Get your free how to work out exchange rates worksheet of 20+ questions and answers. Includes reasoning and applied questions.

How to work out exchange rates examples

Example 1: converting from pounds to a foreign currency.

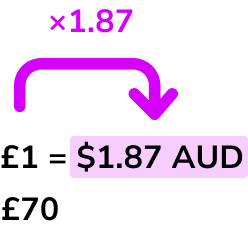

Given the exchange rate between pound and Australian dollars is £1 = \$1.87 , convert £70 to Australian dollars.

In the question we are given,

*Make sure to line up the £1 and £70 as they are the same currency.

2 Highlight the rate.

*This tells us that every £1 is equal to \$1.87.

3 Decide whether to multiply or divide by the rate.

If you are going from the “1” to the other currency then multiply .

If you are going to the “1” from the other currency then divide .

In this case we are going from pounds to Australian dollars so we need to multiply.

4 Multiply or divide the given currency by the exchange rate.

Based on Step 3 , we need to multiply £70 by the rate which is \$1.87.

5 State your final answer with the correct currency symbol.

Example 2: converting from a foreign currency into pounds

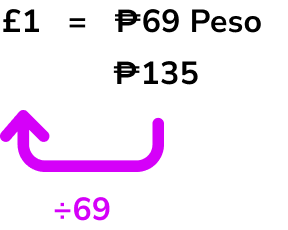

Sally just came back from a visit to the Philippines. In her purse she still had ₱135 (peso) which she wanted to convert back into pounds. A quick check on her foreign exchange app told her the current exchange rate was £1 = ₱69. How many pounds will she get?

\begin{aligned} £1 = \ &₱69 \\\\ &₱135^* \end{aligned}

*Make sure to line up the £1 and ₱135 as they are the same currency.

*This tells us that every £1 is equal to ₱69.

Decide whether to multiply or divide by the rate.

If you are going from the “1” to the other currency then multiply.

In this case we are going from pesos to pound sterling so we need to divide.

Based on Step 3 , we need to divide ₱135 by the rate which is ₱69.

135 \div 69=1.9565...

Example 3: comparing different currencies

In the USA a computer costs \$790. The same mobile phone costs £575 in the UK. Given that the current exchange rate is £1 = 1.35 \ USD, where is the mobile phone cheaper?

£1 = \$1.35 \ USD

We are also asked to compare £575 and \$790. To compare them, we must convert them to the same currency. In this case, we can choose to either convert £575 into US dollars or \$790 into great British pounds (GBP).

For the purposes of this question, we will convert £575 to American dollars.

\begin{aligned} & £1 = \$1.35 \\\\ &£575^* \end{aligned}

*Make sure to line up the £1 and £575 as they are the same currency.

*This tells us that every £1 is equal to \$1.35.

In this case we are going from American dollars to British pounds so we need to multiply.

Based on Step 3 , we need to multiply \$575 by the rate which is \$1.35.

575 \times 1.35=776.25

The computer costs \$776.25 in England and \$790 in the United States.

Therefore, it is cheaper to buy the computer in the UK.

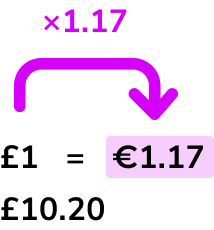

Example 4: worded question

Bonnie is flying home from Spain. She buys some food and drink on the plane.

Bonnie buys 2 chocolate bars, 2 pretzels and a bottle of water. The exchange rate is £1 = €1.17 (euros). She decided to use her leftover euros from her holiday to pay for her bill. Work out the cost of her bill in euros.

£1 = €1.17 \ euros

We are also told that Bonnie buys 2 chocolate bars, 2 pretzels and a bottle of water.

We need to add together the cost of these items.

Total cost = 2 chocolate bars + \ 2 pretzels + \ 1 bottle of water

\begin{aligned} &=(2 \times 1.75)+(2 \times 1.50)+3.70 \\\\ &=£10.20 \end{aligned}

Since this total is in pounds we can put it under the pounds side of the exchange rate.

\begin{aligned} &£1 = €1.17 \\\\ &£10.20 \end{aligned}

*This tells us that every £1 is equal to €1.17.

In this case we are going from pound sterling to euros so we need to multiply.

Based on Step 3 , we need to multiply £10.20 by the rate which is €1.17.

10.20 \times 1.17=11.93

The total cost of her bill in euros is \colorbox{yellow}{$ €11.93.$}

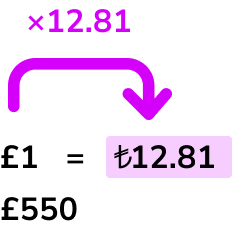

Example 5: worded question

Samantha is planning a holiday to Turkey.

She needs to exchange some of her British pounds into Turkish lira.

The bank only stock ₺100 notes.

Samantha only wants to exchange up to £550 into Turkish lira.

She wants to get as many ₺100 notes as possible.

The current exchange rate is £1=₺12.81.

How many ₺100 notes should she get?

\begin{aligned} &£1=₺12.81 \\\\ &£550^* \end{aligned}

*Make sure to line up the £1 and £550 as they are the same currency.

*This tells us that every £1 is equal to ₺12.81.

In this case we are going from pounds to Turkish lira so we need to multiply.

Based on Step 3 , we need to multiply £550 by the rate which is ₺12.81.

550 \times 12.81=6655

Samantha would get ₺6655 if she converted £550. The bank only stock ₺100 notes so we need to divide ₺6655 by 100 to see how many notes she would get.

This would give us ₺66.55. Since you cannot get 0.55 of a note, this value can be rounded to 66.

She would get \colorbox{yellow}{$\bf{66 \ ₺100} $} notes.

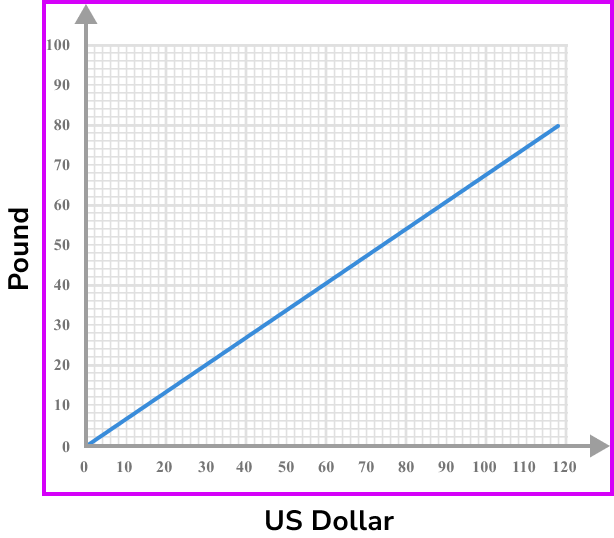

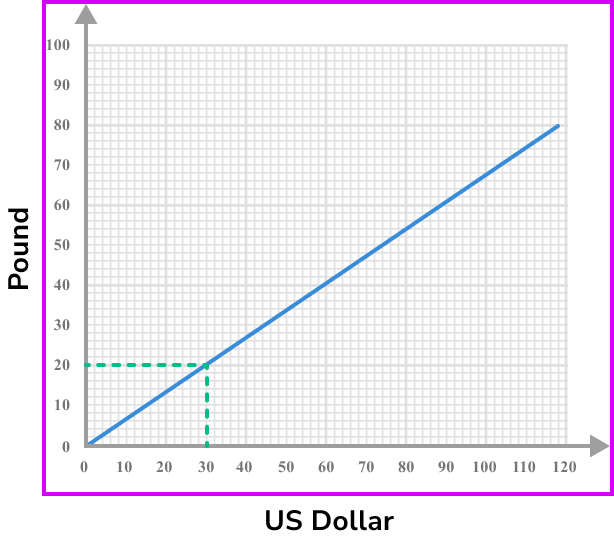

Example 6: conversion graphs

Use the graph below to answer the following questions.

a) Change \$30 USD to pounds.

b) Change £65 to US dollars.

c) Change £100 to US dollars.

a Change \bf{\$30} USD to pounds .

Draw a line going up from \$30 until you hit the line, then look across to the vertical axis and read the value.

In this case \$30 = £20.

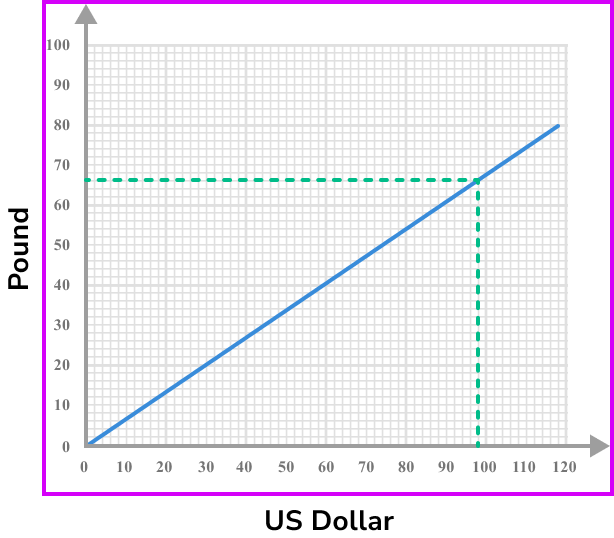

b Change \bf{£65} to US dollars .

Draw a line going across £65 until you hit the line, then look down to the horizontal axis and read the value.

In this case £65 = \$96 USD.

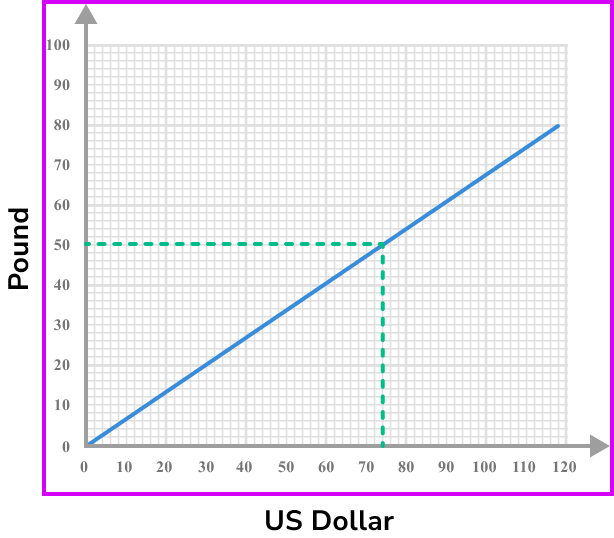

c Change \bf{£100} to US dollars.

Since the graph does not extend to £100, we need to use the values that we know and use them to calculate how many USD £100 is equal to.

Draw a line going across from \$50 USD to the line and down to \$74.

Since we know that

£50 = \$74 .

If we multiply both sides by 2 we get

£100 = \$148 USD.

Step-by-step guide: Conversion graphs

Common misconceptions

- Multiply or divide by the exchange rate

Pupils may get confused whether they need to multiply or divide by the exchange rate. Remember, If you are going from the “1” to the other currency then multiply. If you are going to the “1” from the other currency then divide .

- Lining up the same currencies together

When given information in the question be careful to check what currency the values are in and line up accordingly. If you mix up the currencies it will be difficult to know whether to multiply or divide by the exchange rate.

When rounding, it is usual that we need to round to 2 decimal places. For example, if calculating British pounds we get 231.7851, the final answer would be £217.79. The 2 decimal places would be the pence.

Practice how to work out exchange rates questions

1. Given the exchange rate between British pounds and New Zealand dollars is £1 = \$1.95, convert £90 to New Zealand dollars.

Multiply £90 by the exchange rate 1.95.

This would be £175.70 .

2. Given the exchange rate between British pounds and the Indian rupee is £1 = ₹103.10, convert ₹5000 to pound sterling.

Divide ₹5000 by the exchange rate 103.10.

This would be £48.50 to the nearest pence.

3. In China an iPad costs ¥2500 (Chinese Yuan). The same iPad costs £300 in the UK. Given that the current exchange rate is £1 = ¥8.85, where is the iPad cheaper?

The UK by ¥155

China by ¥2200

China by ¥155

The price is the same in both countries

Convert £300 into Chinese Yuan by multiplying by 8.85.

This would be more expensive than the price in China by ¥155.

4. Lucy is buying some items from an online shop which will accept payments in Pounds and Euros.

She buys: a watch costing £150

a pendant costing £280

a frame costing £17

The exchange rate is £1 = €1.27. Work out the cost of her bill in Euros.

Add up the prices.

Multiply the total by the exchange rate 1.27.

This gives €567.69 .

5. Sangita is planning a holiday to Thailand.

She needs to exchange some of her British pounds into Thai Bahts.

The bank only stock ฿1000 notes.

Sangita only wants to exchange up to £100 into Thai baht.

She wants to get as many ฿1000 notes as possible.

The current exchange rate is £1=฿45.95.

How many ฿1000 notes should she get?

Multiply =£100 by 45.95, then divide by 1000 to determine how many notes she should get.

This gives ฿4595.

We then need to work out the number of ฿1000 notes.

So Sangits would be able to get 4 \ ฿1000 notes.

How to work out exchange rates GCSE questions

1. Samantha goes on holiday to Japan.

She exchanged £850 into Japanese yen.

The exchange rate was £1 = JP¥156.88 .

(a) Change £850 into Japanese yen.

(b) When she returned she had JP¥180 left which she wanted to exchange back into pounds.

She checked the currency exchange rates app on her phone and found that the new rate was £1 = JP¥157.22.

Change JP¥180 into British pounds.

(a) 850 \times 156.88

(b) 180 \div 157.22

2. (a) On a flight back to London from Hong Kong, Jackie purchased the following items from the in-flight dining options.

- A blueberry muffin costing £2.50

- A diet coke costing £3.50

- A tuna sandwich costing £5.50

She paid part of the bill with the HK\$60 left from her holiday and paid the rest in British pounds.

The exchange rate between the British pound and the Hong Kong dollar is £1= HK\$10.68.

How much does Jackie pay in British pounds?

(b) When paying the bill Jackie realised that there was a 10\% service charge on her bill.

What was her total bill in Hong Kong dollars (HKD)? Give your answer to the nearest Hong Kong dollar.

(a) 2.50+3.50+5.50=£11.50

(b) 11.50 \times 1.10=£12.65

3. Paula goes on holiday to Canada.

She exchanged £550 into Canadian dollars.

The exchange rate was £1 = \$1.70 .

(a) Change £550 into Canadian dollars.

(b) While in Canada Paula noticed a blazer she really liked. The blazer cost \$132 \ CDN. She had seen the exact same blazer in England for £79.

Using the same exchange rate as (a), determine where the blazer is cheaper and by how much.

The blazer is cheaper in Canada by \$2.30 .

Alternatively

The blazer is cheaper in Canada by £1.35 .

Learning checklist

You have now learned how to:

- Convert between related units (prices, currencies) in numerical contexts

- Interpret graphs that illustrate direct proportion, such as currencies

The next lessons are

- Units of measurement

- Rate of change

Still stuck?

Prepare your KS4 students for maths GCSEs success with Third Space Learning. Weekly online one to one GCSE maths revision lessons delivered by expert maths tutors.

Find out more about our GCSE maths tuition programme.

Privacy Overview

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 130926

We've now studied ratios and proportions, and we've seen that proportions give us a way to solve problems involving ratios. We turn now to a specific type of ratio, called a rate , and investigate some interesting applications of rates.

In this section, you will learn to:

- Recognize and compute rates and unit rates in context

- Use currency exchange rates to calculate the relative values of different types of currency

- Calculate cost per unit in context, and use cost per unit to determine which of two purchasing options is a better deal

Introduction to Rates

We'll start with a simple example that might be relevant to your daily life.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Let's say that your favorite brand of shampoo is Herbal Essences. Bi-Mart sells \(11.7\) ounces of this shampoo for \(\$5.39\). On the other hand, you can get \(29.2\) ounces of this shampoo for \(\$7.97\) on Amazon . What shampoo would give you the better deal?

Sure, the \(29.2\) ounce shampoo in the above example is more expensive than the \(11.7\) ounce bottle, but does that mean that the more expensive option gives you less value? How can you compare these two quantities when they have different prices and different volumes? Rates can help us answer this question.

Definition: Rate

A rate is a ratio in which the units of the two quantities being compared are different.

In fact, many of the ratios we have seen already are rates. For example, when we computed our hourly pay, we were actually finding a rate, because we compared dollars to hours worked. Other examples of rates include:

- Miles per gallon

- Rotations per minute

- Kilometers per hour

Do you see a pattern with all of these rates? They all have one word in common: the word per . This word, which is often ignored, means "for each" or "for every one" in this context. If you see the word "per" between two units, there's a good chance you are dealing with a rate.

In fact, most of the rates we see in our every day lives are a particular type of rate.

Definition: Unit Rate

A unit rate is a rate expressed so that the denominator of the corresponding ratio is \(1\). (Recall that the "denominator" is the bottom number of the ratio when it is expressed in fraction form.)

Think about the "miles per gallon" example above. If we hear, "this car gets 30 miles per gallon," we know that for every 30 miles driven, the car uses 1 gallon of gas. The number 1 is implicit in the way we express most rates. Even if we are given a rate that is not a unit rate, we can convert it to a unit rate using proportions, as in the example below.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Which of the following are unit rates? For those that are not, convert them to unit rates

- \(5\) miles per hour

- \(7\) feet every \(2\) seconds

- The expression "\(5\) miles per hour" is already a unit rate, since it means "5 miles for every one hour." We can express this ratio in the following way: \[\frac{5 \text{ miles}}{1 \text{ hour}}\] The denominator of this fraction is \(1\), so this is a unit rate.

- The expression "\(7\) feet every 2 seconds" is not a unit rate. As a fraction, it is represented as follows: \[\frac{7 \text{ feet}}{2 \text{ seconds}}\] The fraction above does not have a \(1\) in the denominator, so it is not a unit rate. To convert it into a unit rate, we will set up a proportion involving the ratio above, and an equivalent ratio that does have a 1 in the denominator: \[\frac{7 \text{ feet}}{2 \text{ seconds}} = \frac{x \text{ feet}}{1 \text{ seconds}} \] \[\frac{7 \text{ feet}}{2 \text{ seconds}}\] Now we'll use Cross Multiplication and Division undoes Multiplication to solve for \(x\): \[\begin{align*} 2x &= 7 \\ x &= \frac{7}{2} \\ x & = 3.5 \end{align*} \] That means that a unit rate equivalent to "\(7\) feet every \(2\) seconds" is "\(3.5\) feet every one second." This can be rephrased as "\(3.5\) feet per second," which is more easily understood.

An alternative way to solve the second example would simply to divide \(7 \div 2 = 3.5\). The fact that these alternative ways give the same answer serves to illustrate how useful our method of solving proportions is in different contexts.

Currency Exchange Rates

We'll start by discussing a bit of background about world currencies and how they are used.

There are over \(160\) national currencies in the world. When you travel between two countries that use different currencies, it is necessary to exchange some of one type of currency for the other. This is particularly true in countries where cash is used more frequently that credit/debit cards. It's always a good idea when traveling internationally to carry a small amount of that country's currency in either coins or bills. You can get currency from other countries by ordering it through a bank ahead of your travel. You can also exchange currency at a currency exchange business in the airport, port, or border crossing when you are traveling, though these methods usually have fees associated with them and can be exploitative. In some places, ATMs can be used to dispense currency as well.

But there is a big question here: how much of the other type of currency will you get when you exchange? Most countries do not use the United States Dollar or an equivalent, so this question can be hard to answer. For example, Mexico uses Mexican Pesos as its national currency. At the time this book was written, \(1\) Mexican Peso was worth about \(6\) US cents according to a reliable currency exchange website . That doesn't meant that product cost significantly more or less in either place. The costs of items are scaled to reflect the fact that one Mexican Peso has a relatively smaller value than one US Dollar. For example, a taco plate in Mexico might cost \(90\) Mexican pesos, which is equivalent to \(15\) US Dollars. When the individual units of currency have relatively smaller value, the sticker price on the item goes up. The opposite is also true -- if a currency has a higher value, the items priced in that currency tend to have lower prices. This can be very confusing for travelers.

What's more, these exchange rates change from day to day, depending on international economic factors. At any time, it is possible to look up the exchange rate using the internet, or by going through a bank and asking what exchange rate they are using. There may even be slight discrepancies between these numbers. In this text, we'll use exchange rates that are current at the time of writing according to Google's currency exchange rate lookup feature.

Since currency exchange rates are, at their most basic mathematical level, ratios, we can use our techniques from earlier chapters to solve currency exchange problems. In this section we will avoid using the \(\$\) sign and instead write out "USD" for US Dollar amounts. This helps avoid confusion with symbols, since other countries also use the \(\$\) symbol to mean the currency of that country.

Let's look at a simple example. Please note that example values in this section may not be current as this book is only updated periodically.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Each Japanese Yen is worth \(.0093\) USD. Prior to a trip to Japan, you want to exchange \(250\) US Dollars for Yen. How many Japanese Yen will you get in this exchange? Round to the nearest whole.

We are given the exchange rate of \(1\) Japanese Yen to \(.0093\) US Dollars. Before we start, let's think for a second about this rate: it means that each Yen is equivalent to less than \(1\) US cent, because \(1\) US cent is \(.01\) US dollars, and\(.0093\) is just slightly less than \(.01\). In forming this observation, we can conclude that \(250\) USD will give us a very large amount of Yen, since each USD will be equivalent to over \(100\) Yen.

To actually solve this problem, we set up a proportion that compares Yen to USD, using \(x\) to stand for the quantity we want to find:

\[\frac{1 \text{ Yen}}{.0093 \text{ USD}} = \frac{x \text{ Yen}}{250 \text{ USD}}\]

Notice that we've got the exchange rate we are given on the left, and on the right we've got what we're trying to find. The units are labeled so that we know everything is in the correct place. Now we simply solve this proportion:

Rounding to the nearest whole, we find that we get \[26,882\] Japanese Yen. This may seem like an enormous amount, but based on our observation before starting this problem, it makes sense that the number of Yen is large.

Currency exchange rate problems can always be solved using a method similar to the one above. Depending on the information you are given, your unknown may occur in a different place, but our techniques for solving proportions allow us to find any unknown value, so long as we have all of the other information.

What's the Better Deal?

To introduce this last application of rates, we'll start with an example. Note that throughout this section, we will use the \(\$\) sign again, and all prices are assumed to be in US Dollars. The next example should look familiar to you.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Before attempting to solve this problem, let's understand what is being asked. For our purposes, we consider a choice to be the "best deal" if the cost per unit of the product is lower . In this case, the unit that is used to measure the shampoo is ounces. Therefore, this question could be rephrased as: which of these two purchasing options has the lowest cost per ounce?

In order to solve this question, we want to determine the cost per ounce of each possible purchase. In other words, we want to find the unit rate of cost for each purchase, and the lower unit rate will correspond to the better deal.

For the \(11.7\) ounce shampoo you can buy at Bi-Mart, we can calculate the cost per ounce by dividing the cost by the number of ounces:

\[\frac{\$5.39}{11.7 \text{ ounces}} \approx \$0.46 \text{ per ounce}\]

For the \(\$7.97\) ounce shampoo available on Amazon, we calculate the cost per ounce in the same way:

\[\frac{\$7.97}{29.2 \text{ ounces}} \approx \$0.27 \text{ per ounce}\]

In summary, the \(11.7\) ounce bottle costs \(\$0.46\) per ounce, and the \(29.2\) ounce bottle cost \(\$0.27\) per ounce. That means that the \(29.2\) ounce bottle is a better deal, since it costs less per ounce.

You may have approached the problem above in a different way, by noticing that if you bought two of the \(11.7\) ounce bottles, you'd only have \(23.4\) ounces of shampoo, but have paid \(2 \times \$5.39 = \$10.78\), whereas you could have paid \(\$7.97\) for more shampoo, so Amazon is a better deal. That would be a reasonable way to approach this problem, but not all situations are as easy to calculuate in your head.

These sorts of questions can get trickier if the units involved are not immediately obvious. Let's see another example.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

A pizza parlor sells circular pizzas. A large pizza costs \(\$12\), and a family size pizza costs \(\$16\). A large pizza has a \(12\) inch diameter, and a family size pizza has a \(14\) inch diameter. Which pizza is the better deal?

This problem looks almost too easy at first — certainly the \(12\)-inch pizza is better because it costs a dollar per inch, and the other one costs more per inch!

But wait: what is an "inch" of pizza? That's not a relevant measurement here. The more important unit to consider, when thinking about pizza, is the number of square inches of pizza you get. The area of the pizza is what matters most, not the diameter.

Our first step will therefore be to calculate the areas of the pizza involved. In order to do that, you need to know the area of a circle. The area \(A\) of a circle with radius \(r\) is given by \[A = \pi r^2\] where \(\pi\) is a special constant number related to circles. While \(\pi\) is irrational, meaning a decimal that goes on forever without repeating, it is usually safe to use \(\pi \approx 3.14\) in calculations.

So we proceed to calculate the areas of the two pizzas. The large pizza has a \(12\) inch diameter. The diameter is twice the radius, so this pizza has a \(6\) inch radius. We can find area of the large pizza by calculating \[A_{\text{large}} = \pi r^2 = \pi \cdot (6^2) = 36 \pi \approx 113 \text{ square inches}\]

Similarly, the diameter of the family-size pizza is \(14\) inches, so its radius is \(7\) inches. Therefore, the area of the family-size pizza is given by \[A_{\text{family}} = \pi r^2 = \pi \cdot (7^2) = 49 \pi \approx 154 \text{ square inches}\]

Now that we've got the areas of both pizzas, we can ask: what is the cost per square inch of each pizza? The pizza with the lower cost per square inch will be a better deal.

We find the cost per square inch by dividing the cost of the pizza by the number of square inches. For the large pizza, the cost per square inch is \[\frac{\$12}{113 \text{ square inches}} = \$.106 \text{ per square inch}\]

For the family size pizza, the cost per square inch is \[\frac{\$16}{154 \text{ square inches}} = \$.104 \text{ per square inch}\]

Comparing these two numbers, we see that the \(\$16\) pizza, which was the \(14\) inch family size pizza, has a slightly lower cost per square inch. Therefore, the family size \(14 \)inch pizza is the better deal.

This example illustrates two things:

- It's important to think critically about the question to find the right interpretation. In this case we needed to first find the area of each pizza to make sense of the problem.

- Sometimes cost per unit amounts can be very close, and it's necessary to include many digits following the decimal point. Here it was necessary to go to the third decimal place to see which number was larger.

Keep these things in mind as you answer questions that ask: what is the better deal?

- Write down at least three other examples of rates that were not discussed in this particular chapter.

- Is 8 meters every 5 seconds a unit rate? If not, convert it to a unit rate.

- Is 6 beats per minute a unit rate? If not, convert it to a unit rate.

- Before a trip to Morocco you exchange 300 US Dollars for Moroccan Dirhams. How many Dirhams do you get?

- At the end of the trip, you have 45 Moroccan Dirhams left. If you exchange these for US Dollars, how many Dollars will you get back?

- You are told that \(1\) Swiss Franc is worth \(1.04\) US Dollars, and that \(1\) Russian Ruble is worth \(.014\) US Dollars. On a trip from Switzerland to Russia, you exchange \(50\) Swiss Francs for Russian Rubles. How many Rubles do you get? Round to the nearest whole. [Hint: you can do two separate currency exchange calculations.]

- Suppose that \(32\) ounces of soda costs \(\$1.69\), and \(54\) ounces of the same soda costs \(\$3.47\). Which is the better deal and why?

- You are purchasing land on which to build a home. There are two rectangular lots to choose from. Lot A is \(80\) feet by \(110\) feet, and costs \(\$94,000\). Lot B is \(70\) feet by \(120\) feet, and costs \(\$87,000\). Assuming that all other characteristics of the properties are equally desirable, and you are willing to accept either size lot, which is the better deal and why? [Hint: a rectangle's area is calculated by its length times its width.]

Activity: Currency Conversion

In this activity, you will learn how to convert money between different currencies using an exchange rate table and a calculator.

You will need

- a calculator (or use this calculator )

- A current list of exchange rates (look up on the internet)

The Martin family live in the US and are going to visit many different countries on their vacation.

From their home in New York they travel to Toronto (Canada), London (England), Rome (Italy), New Delhi (India), Tokyo (Japan) and Sydney (Australia), before returning home across the Pacific.

The route is shown on the following map:

Mr. Martin uses his credit card to change money from USD ($US) to the local currency in each of the locations they visit.

Because currencies change all the time, the amount of money Mr. Martin receives in each local currency will change from day to day. But the following table (old data) will give you an idea of how currencies are converted:

You will often see them quoted like "AUD/USD 0.67 16 " meaning that 1 Australian Dollar will get you 0.67 16 USD

Or "USD/JPY 137 .31" meaning that 1 USD will get you 137.31 Japanases Yen.

So which figure should you use?

- The Unit/USD figure tells us how many USD we get for 1 of the other currency.

- The USD/Unit figure tells us how much of the other currency we get per 1 US Dollar

Find today's current exchange rates. Use the internet to find them and fill them in:

Let's look at an example

Mr. Martin converts USD500 to Canadian dollars. How much does he receive?

First find the "Canadian Dollar" row.

Then, because we are converting from the US currency to the Canadian currency, we should use the USD/Unit column:

So he receives USD500 × 1.3634 = CAD681.70

How much will Mr. Martin receive if he changes

- USD1000 to British pounds?

- USD650 to Euro?

- USD400 to Indian Rupees?

Another Example

When the Martin family arrives back in the US from Australia, Mr. Martin finds that he has AUD220 left over and wants to change it back into USD. How much does he receive?

We use the "Australian Dollar" row, and because we are converting from the Australian currency to the US currency, we should use the Unit/USD column:

So he receives AUD220 × 0.67 16 = USD147.75

Mr. Martin also has some other money left over. How much will he receive in USD for:

- 3,500 Indian Rupees?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.3 Monetary Policy and the Equation of Exchange

Learning objectives.

- Explain the meaning of the equation of exchange, MV = PY , and tell why it must hold true.

- Discuss the usefulness of the quantity theory of money in explaining the behavior of nominal GDP and inflation in the long run.

- Discuss why the quantity theory of money is less useful in analyzing the short run.

So far we have focused on how monetary policy affects real GDP and the price level in the short run. That is, we have examined how it can be used—however imprecisely—to close recessionary or inflationary gaps and to stabilize the price level. In this section, we will explore the relationship between money and the economy in the context of an equation that relates the money supply directly to nominal GDP. As we shall see, it also identifies circumstances in which changes in the price level are directly related to changes in the money supply.

The Equation of Exchange

We can relate the money supply to the aggregate economy by using the equation of exchange:

Equation 11.1

The equation of exchange shows that the money supply M times its velocity V equals nominal GDP. Velocity is the number of times the money supply is spent to obtain the goods and services that make up GDP during a particular time period.

To see that nominal GDP is the price level multiplied by real GDP, recall from an earlier chapter that the implicit price deflator P equals nominal GDP divided by real GDP:

Equation 11.2

Multiplying both sides by real GDP, we have

Equation 11.3

Letting Y equal real GDP, we can rewrite the equation of exchange as

Equation 11.4

We shall use the equation of exchange to see how it represents spending in a hypothetical economy that consists of 50 people, each of whom has a car. Each person has $10 in cash and no other money. The money supply of this economy is thus $500. Now suppose that the sole economic activity in this economy is car washing. Each person in the economy washes one other person’s car once a month, and the price of a car wash is $10. In one month, then, a total of 50 car washes are produced at a price of $10 each. During that month, the money supply is spent once.

Applying the equation of exchange to this economy, we have a money supply M of $500 and a velocity V of 1. Because the only good or service produced is car washing, we can measure real GDP as the number of car washes. Thus Y equals 50 car washes. The price level P is the price of a car wash: $10. The equation of exchange for a period of 1 month is

Now suppose that in the second month everyone washes someone else’s car again. Over the full two-month period, the money supply has been spent twice—the velocity over a period of two months is 2. The total output in the economy is $1,000—100 car washes have been produced over a two-month period at a price of $10 each. Inserting these values into the equation of exchange, we have

[latex]\$ 500 \times 2 = \$ 10 \times 100[/latex]

Suppose this process continues for one more month. For the three-month period, the money supply of $500 has been spent three times, for a velocity of 3. We have

[latex]\$ 500 \times 3 = \$ 10 \times 150[/latex]

The essential thing to note about the equation of exchange is that it always holds. That should come as no surprise. The left side, MV , gives the money supply times the number of times that money is spent on goods and services during a period. It thus measures total spending. The right side is nominal GDP. But that is a measure of total spending on goods and services as well. Nominal GDP is the value of all final goods and services produced during a particular period. Those goods and services are either sold or added to inventory. If they are sold, then they must be part of total spending. If they are added to inventory, then some firm must have either purchased them or paid for their production; they thus represent a portion of total spending. In effect, the equation of exchange says simply that total spending on goods and services, measured as MV , equals total spending on goods and services, measured as PY (or nominal GDP). The equation of exchange is thus an identity, a mathematical expression that is true by definition.

To apply the equation of exchange to a real economy, we need measures of each of the variables in it. Three of these variables are readily available. The Department of Commerce reports the price level (that is, the implicit price deflator) and real GDP. The Federal Reserve Board reports M2, a measure of the money supply. For the second quarter of 2008, the values of these variables at an annual rate were

M = $7,635.4 billion

Y = 11,727.4 billion

To solve for the velocity of money, V , we divide both sides of Equation 11.4 by M :

Equation 11.5

Using the data for the second quarter of 2008 to compute velocity, we find that V then was equal to 1.87. A velocity of 1.87 means that the money supply was spent 1.87 times in the purchase of goods and services in the second quarter of 2008.

Money, Nominal GDP, and Price-Level Changes

Assume for the moment that velocity is constant, expressed as V¯ . Our equation of exchange is now written as

Equation 11.6

A constant value for velocity would have two important implications:

- Nominal GDP could change only if there were a change in the money supply. Other kinds of changes, such as a change in government purchases or a change in investment, could have no effect on nominal GDP.

- A change in the money supply would always change nominal GDP, and by an equal percentage.

In short, if velocity were constant, a course in macroeconomics would be quite simple. The quantity of money would determine nominal GDP; nothing else would matter.

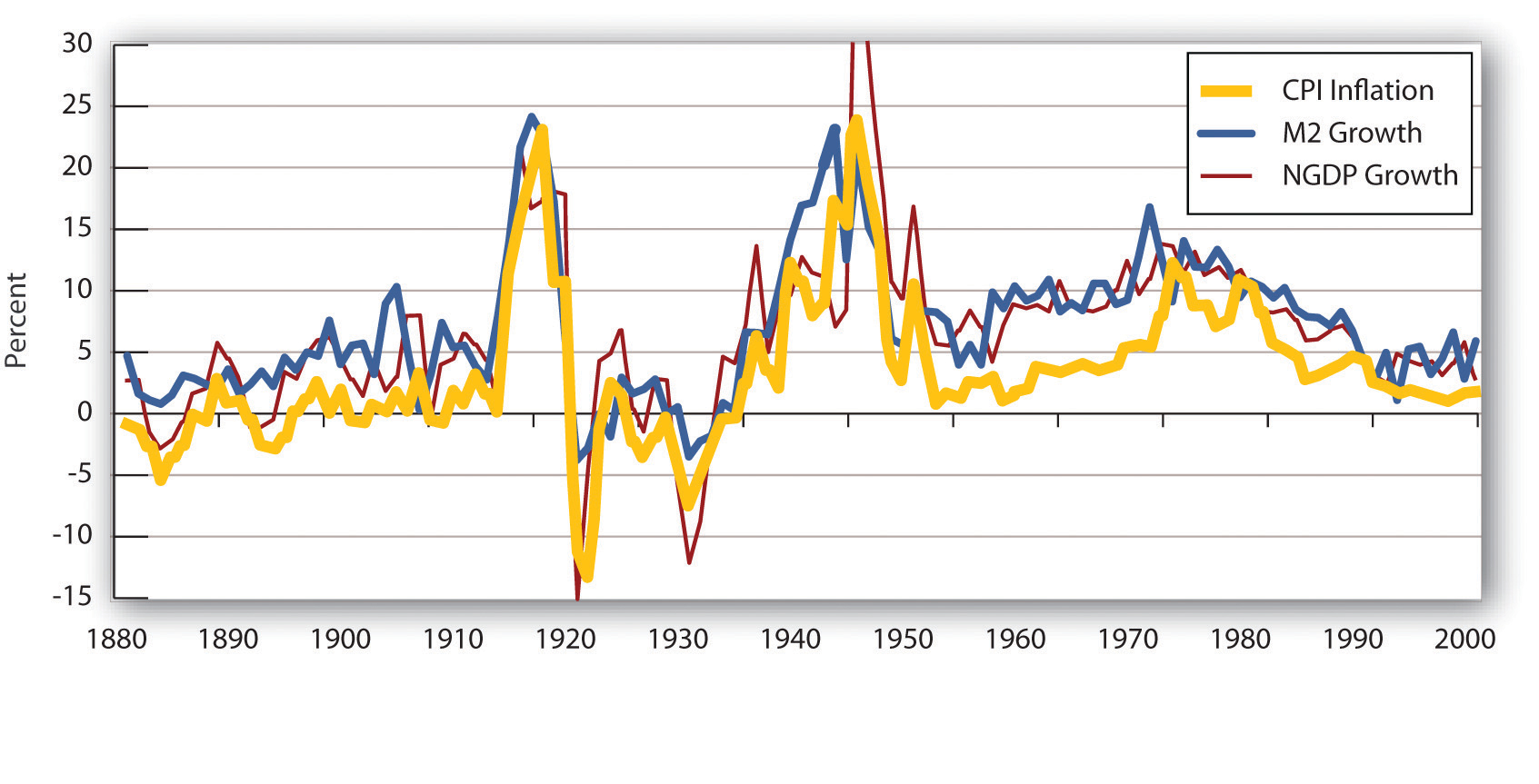

Indeed, when we look at the behavior of economies over long periods of time, the prediction that the quantity of money determines nominal output holds rather well. Figure 11.6 “Inflation, M2 Growth, and GDP Growth” compares long-term averages in the growth rates of M2 and nominal GNP for 11 countries (Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States) for more than a century. These are the only countries that have consistent data for such a long period. The lines representing inflation, M2 growth, and nominal GDP growth do seem to move together most of the time, suggesting that velocity is constant when viewed over the long run.

Figure 11.6 Inflation, M2 Growth, and GDP Growth

The chart shows the behavior of price-level changes, the growth of M2, and the growth of nominal GDP for 11 countries using the average value of each variable. Viewed in this light, the relationship between money growth and nominal GDP seems quite strong.

Source : Alfred A. Haug and William G. Dewald, “Longer-Term Effects of Monetary Growth on Real and Nominal Variables, Major Industrial Countries, 1880–2001” (European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 382, August 2004).

Moreover, price-level changes also follow the same pattern that changes in M2 and nominal GNP do. Why is this?

We can rewrite the equation of exchange, MV¯=PY in terms of percentage rates of change. When two products, such as MV¯ and PV, are equal, and the variables themselves are changing, then the sums of the percentage rates of change are approximately equal:

Equation 11.7

The Greek letter Δ (delta) means “change in.” Assume that velocity is constant in the long run, so that %Δ V = 0. We also assume that real GDP moves to its potential level, Y P , in the long run. With these assumptions, we can rewrite Equation 11.7 as follows:

Equation 11.8

Subtracting %Δ Y P from both sides of Equation 11.8 , we have the following:

Equation 11.9

Equation 11.9 has enormously important implications for monetary policy. It tells us that, in the long run, the rate of inflation, %Δ P , equals the difference between the rate of money growth and the rate of increase in potential output, %Δ Y P , given our assumption of constant velocity. Because potential output is likely to rise by at most a few percentage points per year, the rate of money growth will be close to the rate of inflation in the long run.

Several recent studies that looked at all the countries on which they could get data on inflation and money growth over long periods found a very high correlation between growth rates of the money supply and of the price level for countries with high inflation rates, but the relationship was much weaker for countries with inflation rates of less than 10%. [1] These findings support the quantity theory of money , which holds that in the long run the price level moves in proportion with changes in the money supply, at least for high-inflation countries.

Why the Quantity Theory of Money Is Less Useful in Analyzing the Short Run

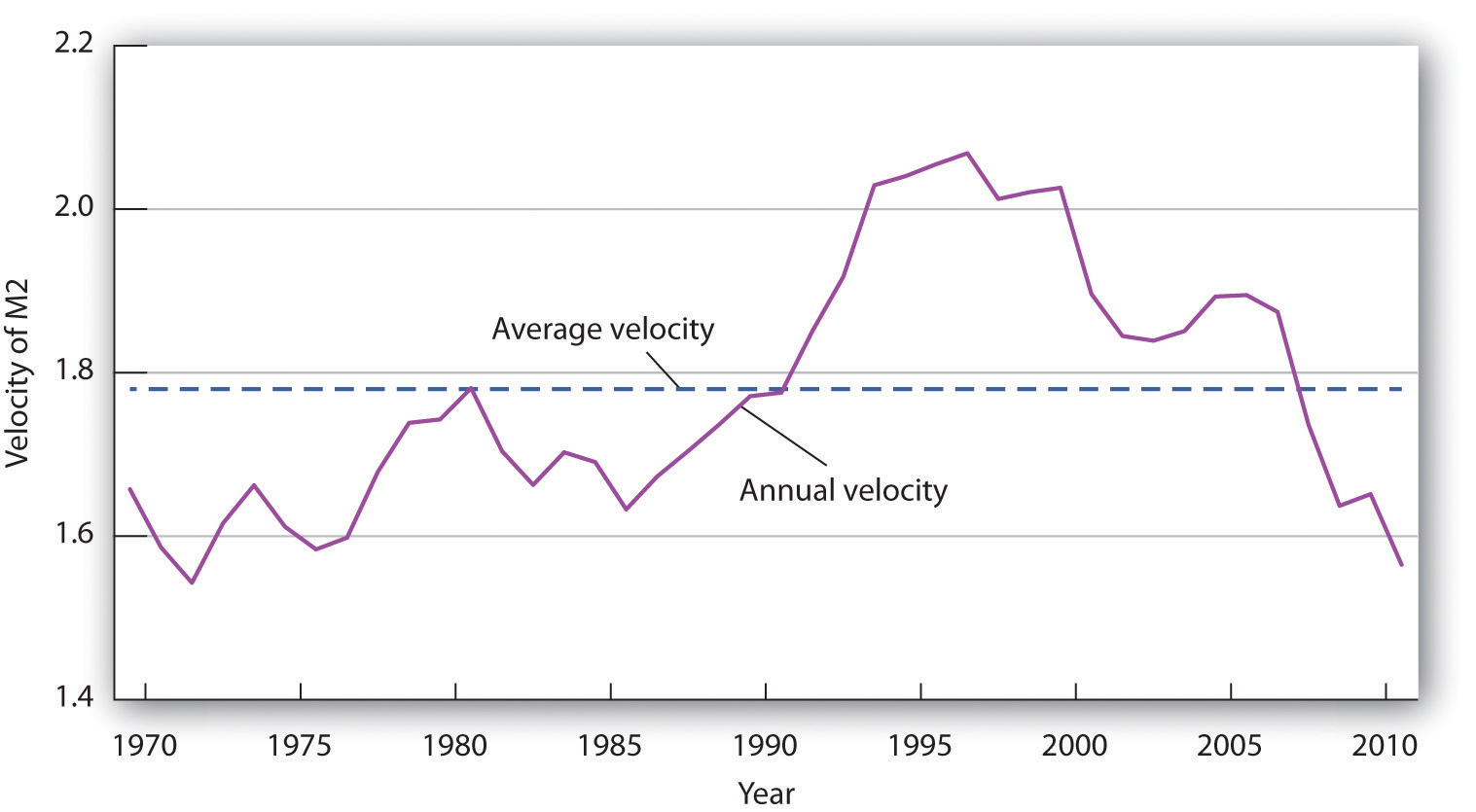

The stability of velocity in the long run underlies the close relationship we have seen between changes in the money supply and changes in the price level. But velocity is not stable in the short run; it varies significantly from one period to the next. Figure 11.7 “The Velocity of M2, 1970–2011” shows annual values of the velocity of M2 from 1960 to 2011. Velocity is quite variable, so other factors must affect economic activity. Any change in velocity implies a change in the demand for money. For analyzing the effects of monetary policy from one period to the next, we apply the framework that emphasizes the impact of changes in the money market on aggregate demand.

Figure 11.7 The Velocity of M2, 1970–2011

The annual velocity of M2 varied about an average of 1.78 between 1970 and 2011.

Source : Economic Report of the President, 2012, Tables B-1 and B-69.

The factors that cause velocity to fluctuate are those that influence the demand for money, such as the interest rate and expectations about bond prices and future price levels. We can gain some insight about the demand for money and its significance by rearranging terms in the equation of exchange so that we turn the equation of exchange into an equation for the demand for money. If we multiply both sides of Equation 11.1 by the reciprocal of velocity, 1/ V , we have this equation for money demand:

Equation 11.10

The equation of exchange can thus be rewritten as an equation that expresses the demand for money as a percentage, given by 1/ V , of nominal GDP. With a velocity of 1.87, for example, people wish to hold a quantity of money equal to 53.4% (1/1.87) of nominal GDP. Other things unchanged, an increase in money demand reduces velocity, and a decrease in money demand increases velocity.

If people wanted to hold a quantity of money equal to a larger percentage of nominal GDP, perhaps because interest rates were low, velocity would be a smaller number. Suppose, for example, that people held a quantity of money equal to 80% of nominal GDP. That would imply a velocity of 1.25. If people held a quantity of money equal to a smaller fraction of nominal GDP, perhaps owing to high interest rates, velocity would be a larger number. If people held a quantity of money equal to 25% of nominal GDP, for example, the velocity would be 4.

As another example, in the chapter on financial markets and the economy, we learned that money demand falls when people expect inflation to increase. In essence, they do not want to hold money that they believe will only lose value, so they turn it over faster, that is, velocity rises. Expectations of deflation lower the velocity of money, as people hold onto money because they expect it will rise in value.

In our first look at the equation of exchange, we noted some remarkable conclusions that would hold if velocity were constant: a given percentage change in the money supply M would produce an equal percentage change in nominal GDP, and no change in nominal GDP could occur without an equal percentage change in M . We have learned, however, that velocity varies in the short run. Thus, the conclusions that would apply if velocity were constant must be changed.

First, we do not expect a given percentage change in the money supply to produce an equal percentage change in nominal GDP. Suppose, for example, that the money supply increases by 10%. Interest rates drop, and the quantity of money demanded goes up. Velocity is likely to decline, though not by as large a percentage as the money supply increases. The result will be a reduction in the degree to which a given percentage increase in the money supply boosts nominal GDP.

Second, nominal GDP could change even when there is no change in the money supply. Suppose government purchases increase. Such an increase shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right, increasing real GDP and the price level. That effect would be impossible if velocity were constant. The fact that velocity varies, and varies positively with the interest rate, suggests that an increase in government purchases could boost aggregate demand and nominal GDP. To finance increased spending, the government borrows money by selling bonds. An increased supply of bonds lowers their price, and that means higher interest rates. The higher interest rates produce the increase in velocity that must occur if increased government purchases are to boost the price level and real GDP.

Just as we cannot assume that velocity is constant when we look at macroeconomic behavior period to period, neither can we assume that output is at potential. With both V and Y in the equation of exchange variable, in the short run, the impact of a change in the money supply on the price level depends on the degree to which velocity and real GDP change.

In the short run, it is not reasonable to assume that velocity and output are constants. Using the model in which interest rates and other factors affect the quantity of money demanded seems more fruitful for understanding the impact of monetary policy on economic activity in that period. However, the empirical evidence on the long-run relationship between changes in money supply and changes in the price level that we presented earlier gives us reason to pause. As Federal Reserve Governor from 1996 to 2002 Laurence H. Meyer put it: “I believe monitoring money growth has value, even for central banks that follow a disciplined strategy of adjusting their policy rate to ongoing economic developments. The value may be particularly important at the extremes: during periods of very high inflation, as in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the United States … and in deflationary episodes” (Meyer, 2001).

It would be a mistake to allow short-term fluctuations in velocity and output to lead policy makers to completely ignore the relationship between money and price level changes in the long run.

Key Takeaways

- The equation of exchange can be written MV = PY .

- When M , V , P , and Y are changing, then %Δ M + %Δ V = %Δ P + %Δ Y , where Δ means “change in.”

- In the long run, V is constant, so %Δ V = 0. Furthermore, in the long run Y tends toward Y P , so %Δ M = %Δ P .

- In the short run, V is not constant, so changes in the money supply can affect the level of income.

The Case in Point on velocity in the Confederacy during the Civil War shows that, assuming real GDP in the South was constant, velocity rose. What happened to money demand? Why did it change?

Case in Point: Velocity and the Confederacy

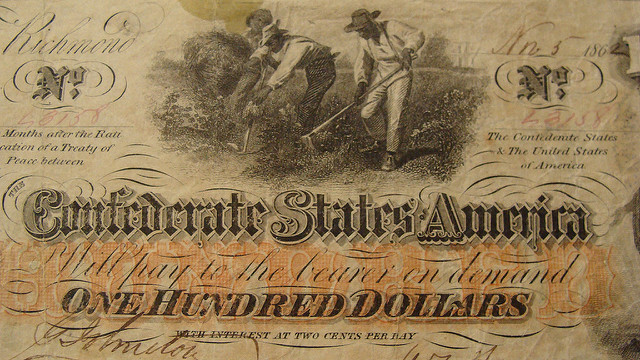

Hannah – Confederate Money – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The Union and the Confederacy financed their respective efforts during the Civil War largely through the issue of paper money. The Union roughly doubled its money supply through this process, and the Confederacy printed enough “Confederates” to increase the money supply in the South 20-fold from 1861 to 1865. That huge increase in the money supply boosted the price level in the Confederacy dramatically. It rose from an index of 100 in 1861 to 9,200 in 1865.

Estimates of real GDP in the South during the Civil War are unavailable, but it could hardly have increased very much. Although production undoubtedly rose early in the period, the South lost considerable capital and an appalling number of men killed in battle. Let us suppose that real GDP over the entire period remained constant. For the price level to rise 92-fold with a 20-fold increase in the money supply, there must have been a 4.6-fold increase in velocity. People in the South must have reduced their demand for Confederates.

An account of an exchange for eggs in 1864 from the diary of Mary Chestnut illustrates how eager people in the South were to part with their Confederate money. It also suggests that other commodities had assumed much greater relative value:

Sources : C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chestnut’s Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981), 749. Money and price data from E. M. Lerner, “Money, Prices, and Wages in the Confederacy, 1861–1865,” Journal of Political Economy 63 (February 1955): 20–40.

Answer to Try It! Problem

People in the South must have reduced their demand for money. The fall in money demand was probably due to the expectation that the price level would continue to rise. In periods of high inflation, people try to get rid of money quickly because it loses value rapidly.

Meyer, L. H., “Does Money Matter?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 83, no. 5 (September/October 2001): 1–15.

- For example, one study examined data on 81 countries using inflation rates averaged for the period 1980 to 1993 (John R. Moroney, “Money Growth, Output Growth, and Inflation: Estimation of a Modern Quantity Theory,” Southern Economic Journal 69, no. 2 [2002]: 398–413) while another examined data on 160 countries over the period 1969–1999 (Paul De Grauwe and Magdalena Polan, “Is Inflation Always and Everywhere a Monetary Phenomenon?” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 107, no. 2 [2005]: 239–59). ↵

Principles of Macroeconomics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Get 25% off all test packages.

Get 25% off all test packages!

Click below to get 25% off all test packages.

How To Do Currency Conversion In Numerical Reasoning Tests

What is a currency conversion question.

Alongside questions on fractions, sequences, charts and basic algebra, a numerical reasoning test will likely include questions on calculating exchange rates.

These questions will involve a currency pair, the exchange rate and a conversion amount. You will be asked to calculate the amount of one currency in the pair received, when converting a volume of the other.

Currency conversation tends not to be a common calculation in our everyday lives. Unless you are an active trader in the forex market, trips abroad are the main context for encountering exchange rates. The calculation is, however, simple to perform once the basic method is grasped.

Success in a numerical reasoning test requires speed and accuracy, so learning how to calculate currency conversion questions rapidly will be of aid when taking the test. Becoming accustomed to the information given, and the calculations required in different question scenarios, will ensure you can tackle any exchange rate question, regardless of the context.

How to read exchange rates

Reading exchange rates is a simple procedure. An exchange rate is made up of a currency pair, and at any given time displays a snapshot into the relationship between the two currencies.

In an exchange rate, the first currency listed stands for one unit of that currency. The exchange rate (typically shown to two decimal places in numerical reasoning questions) indicates what value of the latter currency would purchase one unit of the former.

For example, you may be given the following information:

EUR/USD 1.21

This means that it costs US$1.21 to purchase €1 or, in other words, €1 = US$1.21. From this, you can also calculate how much it costs to buy US$1 using EUR, by dividing 1 by the exchange rate.

1/1.21 = 0.82

So, this means it costs €0.82 to purchase US$1 or, in other words, US$1 = €0.82. This price is reflected in the inverted currency pair:

USD/EUR 0.82

You may be faced with questions that ask about the first or the second currency in the given pair.

The currency pairs used in the questions may vary and could include popular currencies such as the GBP (British Pound), CHF (Swiss Franc), CAD (Canadian Dollar), AUD (Australian Dollar), NZD (New Zealand Dollar) and JPY (Japanese Yen).

Recognising these abbreviations as relating to currency will help you to rapidly identify a currency conversion question. Regardless of the currencies involved, the way to read the implications of an exchange rate and the conversation calculation steps remain the same.

How to calculate currency conversion

In a currency conversion question, you may get the currency information as part of an explanation, or as statistics in a table. Either way, all the information you need to calculate the answer will be within the question.

You may be asked to calculate the volume of one currency you would receive from a given exchange rate and currency amount. For example:

Sarah has US$750 to convert into GBP for her upcoming trip. The exchange rate currently stands at USD/GBP 0.73. How much money will she have in GBP?

You are being asked to find the volume of the second currency in the pair. First read the exchange rate. In this case, $1 USD = £0.73 GBP.

To calculate the number of British Pounds US$750 yields from this USD/GBP exchange rate, the calculation is as follows:

Unknown currency amount (second currency) = Known currency amount (first currency) x Exchange rate

Exchange rate: USD/GBP 0.73

GBP = USD$750 x 0.73

GBP = £547.50

To convert back to check the amount, divide the number of British Pounds by 0.73 to get the number of US dollars.

If the question gave the same exchange rate information of USD/GBP 0.73, but instead Sarah was intending to convert £750 into US Dollars, the calculation required would be as follows:

You are being asked to find the volume of the first currency in the pair. First, read the exchange rate given: USD/GBP 0.73 (US$1 = £0.73).

Unknown currency amount (first currency) = Known currency amount (second currency) / Exchange rate

USD = GBP £750 / 0.73

USD = $1027.40

The logic behind this is that (as indicated in the How to Read Exchange Rates section), from the information USD/GBP 0.73, we can calculate that £1 = US$1.37 by doing the calculation 1/0.73.

$1.37 x the US$750 Sarah holds = USD $1,027.40

It is important to understand the mechanics of how each conversion amount is calculated and why it is so. This will ensure you can tackle currency conversion in any context or arrangement.

You may also be asked questions involving currency conversion commissions. These involve skills around both currency conversion and percentages. For example:

Tom is converting CAD $200 into EUR, but his provider is charging a 5% commission on the transaction. The exchange rate is CAD/EUR 0.64. How much money (in EUR) does Tom receive to take on holiday?

EUR = CAD $200 x 0.64

5% of 128 = 128 – 5%

The logic behind this is that:

To find 5%: €128 x 5% = €6.40

To calculate the final amount received: €128 – €6.40 = €121.60

Whilst these calculations are fairly simple, understanding the mechanisms will help you to answer the currency conversion questions confidently, regardless of the figures involved.

Enjoy what you’ve read? Let others know!

- Share on whatsapp

- Share on linkedin

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

- Share via email

By using our website you agree with our Cookie Policy.

- AON Hewitt G.A.T.E.

- PI Cognitive Assessment (PLI Test)

- Korn Ferry Leadership Assessment

- Berke Assessment

- Ergometrics

- Thomas International

- Predictive Index (PI)

- NEO Personality Inventory

- Leadership Assessment

- Gallup’s CliftonStrengths

- Sales Personality Tests

- Personality Management Tests

- Saville Wave

- McQuaig Word Survey

- Bell Personality Test

- Myers Briggs Personality Test

- DISC Personality Test

- Management SJT

- Supervisory SJT

- Administrative SJT

- Call Center SJT

- Customer Service SJT

- Firefighter SJT

Numerical Reasoning Tests

- Verbal Reasoning Tests

- Logical Reasoning Tests

- Cognitive Ability Tests

- Technical Aptitude Tests

- Spatial Reasoning Tests

- Abstract Reasoning Test

- Deductive Reasoning Tests

- Inductive Reasoning Tests

- Mechanical Reasoning Tests

- Diagrammatic Reasoning Tests

- Fault Finding Aptitude Tests

- Mathematical Reasoning Tests

- Critical Thinking Tests

- Analytical Reasoning Tests

- Raven’s Progressive Matrices Test

- Criteria’s CCAT

- Matrigma Test

- Air Traffic Controller Test

- Administrative Assistant Exam

- Clerical Ability Exam

- School Secretary Tests

- State Trooper Exam

- Probation Officer Exam

- FBI Entrance Exam

- Office Assistant Exam

- Clerk Typist Test

- Police Records Clerk Exam

- Canada’s Public Service Exams

- Firefighter Exams

- Police Exams

- Army Aptitude Tests

- USPS Postal Exams

- Hiring Process by Professions

Select Page

How to Solve Currency Conversion Questions in Numerical Reasoning Tests

Ever heard the expression “you can’t compare apples and oranges”? Well the same could be said for currencies. You can’t compare dollars and yen, unless of course you convert the sums properly first. As it turns out, many numerical reasoning tests contain currency conversion questions that ask you to do exactly that.

Below, we’ll discuss why psychometric exams ask currency questions and how job-seekers can best prepare for these screening questions.

What Are Currency Conversion Questions?

If you plan to travel, either for leisure or business, you’re going to find yourself working with other currencies. Whether you’re planning an exotic vacation or flying in for a graduate conference, you’ll need to know how to convert the money you have into the local currency so you can budget for expenses properly. The exchange rate questions on pre-employment aptitude assessments will test to see if you can do just that.

You might also need to convert between currencies if you’re making a purchase online or conducting business with an overseas partner. Investors always make sure to assess the value of the local currency before contributing money to an initiative.

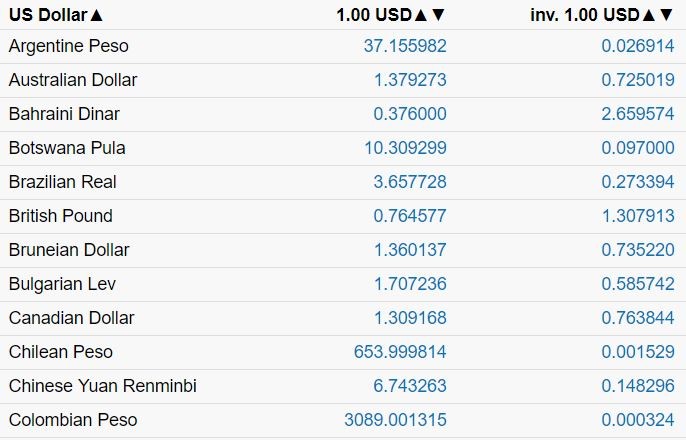

The table above compares different major currencies from countries around the world. Each currency is labelled with the flag of the respective country and the international three-letter abbreviation.

Be careful to read the chart only from left-to-right and not from top-to-bottom. Just start in the left-hand column and read across until you reach the correct column. One bill of the currency in the left-hand column will be worth the number shown of the currency at the top of the respective column. That is to say that 1 USD is equal to 1.3792 AUD and NOT 0.72464 AUD.

How to Solve Currency Conversion Questions?

In order to solve currency conversion problems, you’re going to have to set up proportions relating the exchange rate values presented in the table to the ones you want to determine.

For instance, let’s say I’m travelling from New York to Japan and want to exchange 250 USD into Japanese yen to cover my expenses during my stay. How many Japanese yen will I receive in return for 250 USD?

I’m going to set up a proportion with USD on the top and JPY on the bottom using X for the amount of yen I will receive in return—the sum we want to find.

USD = 1 = 250 JPY 109.526 X

By cross-multiplying, I come up with the following:

X= 27,381.5

In some problems, you’ll have to divide to isolate the variable, but in this question, we get the answer right away. For 250 USD, you’ll receive 27,381.5 JPY.

Which Currency Is Stronger?

We say that one currency is stronger than another if one bill from one currency can purchase more than one bill in another. For instance, if one pound can buy two dollars, we would say the Great British pound is stronger than the United States dollar.

Currency Conversion Tips:

Check out our best currency transformation tips so you’re well prepared when you arrive at the assessment center!

- Check Twice Make sure you check the chart twice before solving the question. You don’t want to answer incorrectly just because you entered the wrong information.

- Keep Values Organized When you set up a proportion, make sure to label carefully. You want to make sure to keep similar values on the same side of the proportion.

- One Step At A Time Sometimes, you’ll have to complete multiple equations to convert from one currency to the another . If this is the case, make sure to keep each equation separate and organized so you can easily check your work later.

Free Currency Conversion Practice:

Put your skills to the test with the currency exchange questions below!

- According to the chart above, 260 USD is equal to how many Argentine Pesos. Round your answer to two places past the decimal point.

- How many Chinese yuan will I receive for 100 Brazilian Real according to the rates in the chart above? Round your answer to the nearest hundredth.

- Currency Conversion Questions

- Numerical Reasoning Tables

- Numerical Critical Reasoning Test

- Advanced Numerical Reasoning Tests

- Non-Calculator Numerical Test

- Percentages in Numerical Tests

- Graphs in Numerical Reasoning Tests

- Ratios in Numerical Reasoning Tests

- Number Series Tests

- Basic Numeracy Test

- How to Use a Numerical Calculator?

- Numerical Computation Test

Aptitude Tests

- Aptitude Tests Guide

- Numerical Reasoning Test

- Verbal Reasoning Test

- Cognitive Ability Test

- Critical Thinking Test

- Logical Reasoning Test

- Spatial Reasoning Test

- Technical Aptitude Test

- Inductive Reasoning Test

- Analytical Reasoning Test

- Deductive Reasoning Test

- Mechanical Reasoning Test

- Non-Verbal Reasoning Tests

- Diagrammatic Reasoning Test

- Concentration Assessment Test

- Finance Reasoning Aptitude Test

- Fault Finding (Fault Diagnosis) Test

- Senior Management Aptitude Tests

- Error Checking Tests

- In-Basket Exercise

How to deal with exchange rate risk

If your business exports or imports goods or services, you need to consider how you will protect yourself against changes in the exchange rate. Even a tiny variation in the rate could cost your business thousands of pounds.

You’ll also need to decide how to make and receive payments in foreign currencies.

This guide is aimed at businesses that regularly deal with customers who are based outside of the UK. It explains how to price goods or services, how to combat the risk of exchange rate changes and the practicalities of dealing in foreign currencies.

Foreign currency issues when importing or exporting

Businesses which import or export goods need to bear in mind a number of key issues when making transactions in foreign currencies:

- Foreign currency transactions are sensitive to fluctuations in the exchange rate. A price you agree with a customer or supplier on one day could rise or fall if the exchange rate changes. This is especially true in the current economic climate where currency is fluctuating on a daily basis making it more difficult to keep track of exchange rates. But there are steps you can take to protect yourself against these. (See the section in this guide on how to identify foreign exchange risks).

- If you’re exporting, you must decide whether it’s best to price your goods or services in the local currency of the country with which you’re trading. The decision will depend on individual circumstances and on factors such as how you want to present yourself in that market and how your competitors set their prices.

- If you’re importing components priced in a foreign currency that form part of goods you’re selling in sterling, you’ll need to decide how to price those goods to reflect the exchange rate.

- If you are trading with companies in the eurozone (i.e. the European Union member states that use the euro) there are many practices and standards to make life easier. See our guide on trading in the European Union.

Identify foreign exchange risks

When your business deals in a foreign currency you are exposed to certain risks.

For example, you might find that after agreeing a price for exported or imported goods the exchange rate changes before delivery. Clearly, this can work both for and against you.

Some currencies are more volatile than others because of their unstable economies or inflation. However, the current economic climate is also impacting more stable currencies such as the euro and the US dollar. Your bank should be able to advise you about this.

As exchange rates can go both up and down, it can be tempting to gamble that this will work out in your favour. However, this is extremely risky and could land you with a significant financial loss.

It’s safer to reduce the risk by using one of the forms of hedging available through a bank. Hedging simply means insuring against the price of currency moving against you in the future. There are many different types of currency hedging and your bank should be able to help you with the best solutions for your business.

You could trade overseas in sterling – effectively transferring the foreign exchange risk to the business you’re dealing with. Whether this is appropriate will depend on the product in question and the relative bargaining strength of you and your trading partner.

Bear in mind that exchange rates could have an effect on your business’ competitiveness even if you don’t trade overseas. When a country’s currency loses value against the pound, imports from that country into the UK become cheaper, so you may have to respond to aggressive pricing from competitors who source from that country.

Similarly, if a country’s currency gains value against sterling, UK exports to that country become cheaper.

This article was first published by Business Link.

Foreign Currency and Exchange Rate Risks © Crown Copyright 2012. Source: www.businesslink.gov.uk

Barclays can help you export successfully

Barclays Business Abroad is a package of discounts and banking tools that can give you a great start in the world of international trade. The package includes all the following:

- Introduction to international trading workshop – an immersive workshop that’ll equip you with the knowledge and capabilities you need to better deal with the pressures of international trade

- Free currency accounts

- 25% discount on all outgoing and incoming international payments

- 25% discount on export document preparation

- 40% discount on credit reports (which help you control your business’ exposure to international risk by giving you accurate information on new overseas customers and suppliers)

- Free exchange rate iAlerts – keeping you up to date with any rate fluctuations that could affect your trading

- Our Exchange Rate Risk interactive online tool will help you understand the level of risk you’re dealing with and the potential impact on your business.

Step by Step

- Getting started

- Selecting a market

- Reaching customers

- Pricing and getting paid

- Delivery and documentation

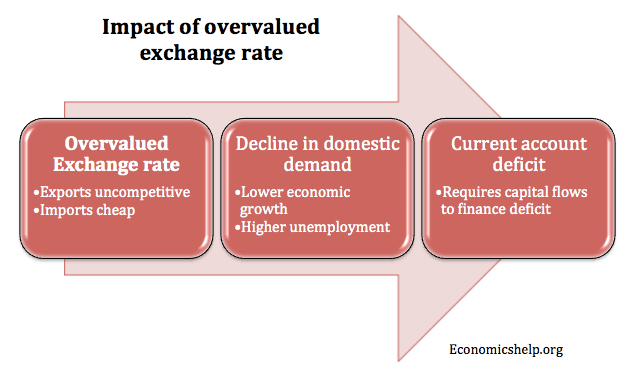

Problems of Overvalued Exchange Rate

An overvalued exchange rate implies that a countries currency is too high for the state of the economy. An overvalued exchange rate means that the countries exports will be relatively expensive and imports cheaper. An overvalued exchange rate tends to depress domestic demand and encourage spending on imports.

An overvalued exchange rate can also be measured by looking at purchasing power parity PPP . An overvalued exchange rate will mean goods are relatively more expensive in that country. (a more sophisticated form of PPP also takes into account difference in real GDP per capita – Beefed up Big Mac Index at Economist)

An overvalued exchange rate is particularly a problem during a period of sluggish growth. If the economy is booming, an overvalued exchange rate can help reduce inflationary pressure, but in a recession, an overvalued exchange rate can cause further deflationary pressures.

Examples of Overvalued Exchange Rates

2011 – Switzerland and Japan

In 2011, both Switzerland and Japan witnessed an appreciation in their currency. This appreciation occurred because investors were worried about finding secure investments in a period of economic uncertainty. However, because the global economy remained depressed (slow growth, high unemployment), this appreciation was unwelcome. It makes it more difficult to export goods and can lead to lower growth. For an economy like Japan which relies on a strong export sector, this decline in competitiveness could be damaging to their economy.

This is why both Switzerland and Japan sought to intervene to try and reduce the value of their currency.

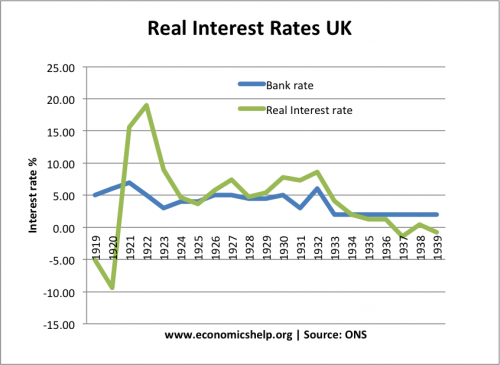

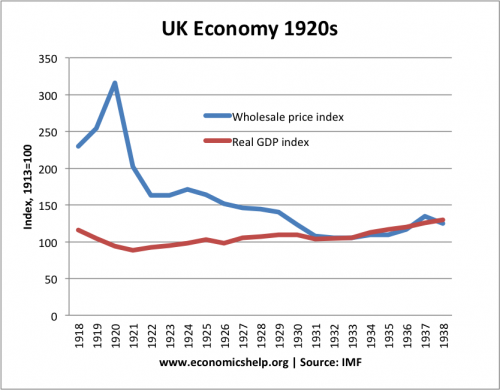

1992 – UK in the Exchange rate mechanism

In 1990-92, the UK was in the exchange rate mechanism, which involved keeping value of the Pound fixed. But, due to relatively high inflation, markets were putting downward pressure on the Pound and the government had to keep rising interest rates. This caused the recession of 1992. See more detail at ERM

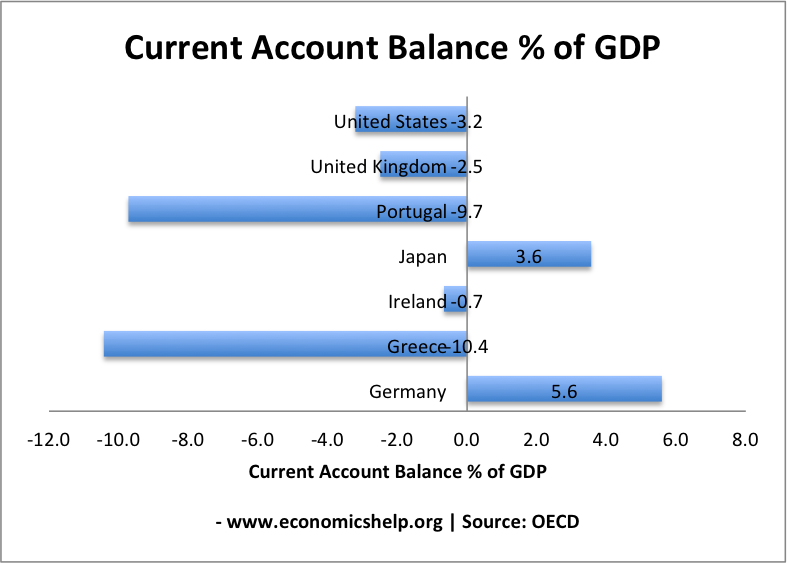

Overvalued Exchange Rates in the Euro