- Speech Crafting →

How to Write an Effective Manuscript Speech in 5 Steps

If your public speaking course requires you to give a manuscript speech, you might be feeling a little overwhelmed. How do you put together a speech that’s effective and engaging? Not to worry – with a few simple steps, you’ll be prepared to pull off a manuscript speech that’s both impactful and polished. In this post, we’ll walk through the 5 steps you need to follow to craft an effective manuscript speech that’ll leave your audience impressed. So let’s get started!

Quick Overview of Key Question

A manuscript speech involves writing down your entire speech word-for-word and memorizing it before delivering it. To begin, start by writing down your introduction , main points, and conclusion. Once you have written your speech, practice reading it out loud to get used to the phrasing and memorize each part .

Preparing a Manuscript Speech

When preparing for your manuscript speech, it is essential to consider both the content of your speech and the format in which you will deliver the speech. It is important to identify any key points or topics that you would like to cover in order to ensure that your manuscript is properly organized and succinct. Additionally, when selecting the style of delivery, be sure to choose one that best fits with your specific message and goals . One style of delivery includes utilizing a conversational tone in order to engage with your audience and help foster an interactive environment . When using this delivery style, be sure to use clear and concise language as well as humor and anecdotes throughout your speech . In addition, select a pacing that allows for flexibility with audience responses without detracting from the overall structure or flow of your text. Alternatively, another style of delivery involves reading directly from the manuscript without deviating from the text. This method works best when coupled with visual aids or props that support the information being relayed. Additionally, it is important to remember to practice reading the manuscript aloud several times prior to its delivery in order to ensure quality content and an acceptable rate of speed. No matter which delivery style you decide upon, careful preparation and rehearsal are essential components of delivering an effective manuscript speech. After deciding on a style of delivery and organizing the content of your speech accordingly, you can move on to formatting your document correctly in order to ensure a professional presentation during its delivery.

Document Format and Outline Structure

Before you dive into the content research and development stages of crafting your manuscript speech, it is important to consider the structure that your specific delivery will take. The format of your document can be varied depending on preferences and requirements, but always remember to keep it consistent throughout. When formatting your document, choose a universal style such as APA or MLA that may be easily recognisable to readers and familiar to most academics. Not only should this ensure your work meets some basic standards, but it will also make sure any information sources are appropriately cited for future reference. Additionally, you should provide visibility for headings to break up topics when needed, whilst keeping the language succinct and easy to understand. Creating an outline is integral in effectively structuring both a written piece of work and delivering a speech from paper. Use a hierarchical system of divisional points starting with a central concept, followed by additional details divided into sub sections where necessary and ending with a conclusion. This overview will act as a roadmap during the writing process—keeping track of ideas, identifying gaps in the presentation structure, and helping ensure clarity when presenting your points live on stage. It may be best practice to include a few statements or questions at the end of each key point to challenge thought in your audience and keep them engaged in the conversation. This could prompt new ideas or encourage defined discussion or debate amongst viewers. Depending on the topic itself, introducing two sides of an argument can allow an all-encompassing view point from which all members of an audience can draw their conclusions from majority opinion. Once you’ve established a full document format and outlined its corresponding structure for delivery, you’re ready for the next step: carefully developing comprehensive content along with appropriate ideas behind each sentence, word choice , and syntax used in every phrase. With these vital pieces in place, you are one step closer to creating an effective manuscript speech!

Content, Ideas and Language

The content, ideas, and language you use in your manuscript speech should be tailored to the audience you are addressing. It is important to consider the scope of the audience’s knowledge, level of interest in the topic and any special needs or cultural sensitivities. The most obvious way of doing this is by understanding who will be listening to the speech. You can also research the subject matter thoroughly to ensure you have a well-rounded perspective on the issue and that your opinion is well-informed.

While incorporating facts and personal experiences can help make any point stronger, ensure all ideas included in the speech have a relevancy to the main argument. Finally, avoid using difficult words or jargons as they may detract from any points being made. In terms of language, it’s recommended to use an active voice and write plainly while maintaining interesting visuals. This will help keep listeners engaged and make it easy for them to understand what’s being said. Additionally, focus on using appropriate vocabulary that will sound classy and create a good impression on your audience. Use simpler terms instead of long-winded ones, as regularly as possible, so that your message integrates easier with listeners. Now that you’ve considered content ideas and language for your manuscript speech, it’s time to go forward with writing and practicing it.

Writing and Practicing a Manuscript Speech

When writing a manuscript speech, it’s important to choose a central topic and clearly define the message you want to convey. Start by doing some research to ensure that your facts are accurate and up-to-date. Take notes and begin to organize your points into a logical flow. Once the first draft of your speech is complete, read it over multiple times, checking for grammar and typos. Also consider ways to effectively utilize visuals, such as photos or diagrams, as props within your speech if they will add value to your content. It is essential to practice delivering your speech using the manuscript long before you stand in front of an audience. Time yourself during practice sessions so that you can get comfortable staying within the parameters provided for the speech. Achieving a perfect blend of speaking out loud and reading word-by-word from the script is a vague area that speakers must strike a balance between in order to engage their audience without appearing overly rehearsed or overly off-the-cuff. Finally, look for opportunities to get feedback on your manuscript speech as you progress through writing and practicing it. Ask family members or friends who are familiar with public speaking for their input, or join an organization like Toastmasters International – an organization dedicated to improving public speaking skills – for more constructive criticism from experienced professionals. Crafting a powerful story should be the next step in preparing for an effective manuscript speech. Rather than delivering cold data points, use storytelling techniques to illustrate your point: Describe how others felt when faced with a challenge, what strategies they used to overcome it, and how their lives changed as a result. Telling stories makes data memorable, entertaining and inspiring – all qualities which should be considered when writing an engaging manuscript speech.

Crafting a Powerful Story

A powerful story is one of the most important elements of a successful manuscript speech. It is the main ingredient to make your speech memorable to the audience and help it stand out from all the other speeches. When crafting a story, there are a few things you should consider: 1) Choose an Appropriate Topic: The topic of your story should be appropriate for the type of speech you will be giving. If you are giving a motivational speech , for example, ensure your story has an uplifting message or theme that listeners can take away from it. Additionally, avoid topics that are too controversial so as not to offend any members of the audience. 2) Relay Your Experience: You could also use your own experience to create powerful stories in your manuscript speech. This gives listeners an authentic perspective of the topic and makes them feel connected to you and your message. Besides personal experiences, you may also draw stories from current events and movies/books which listeners can relate to depending on their age group. 3) Be Animated: As you deliver your story, be sure to convey emotions with proper tone and gestures in order to keep the audience engaged and increase its resonance. Using props and visual aids can also complement the delivery of your story by making it more experiential for listeners. Finally, before moving on to writing the rest of the manuscript speech, ensure that you have developed a powerful story that captures the hearts of those who hear it. With a great story to start off with, listeners will become more invested in what is about to come next in this speech – some tips for delivery!

Key Points to Remember

Writing a powerful story is essential to creating a successful manuscript speech. When selecting topics and stories, it’s important to consider the type of speech, the message, and making sure it’s appropriate and isn’t offensive. Drawing from personal experience and current events can enhance the audience’s connection with the topic, while being animated with tone and gestures will make it more engaging. Visual aids and props can complement this as well. Introducing a great story will draw people to your speech and help them get invested in what comes next.

Tips for Delivery of a Manuscript Speech

Delivering a manuscript speech effectively is essential for making sure your message gets across to your audience. While it may seem daunting, by following a few simple tips, you can ensure that you present your speech in the most professional manner possible. Before you start delivering your speech, be sure to practice it several times in advance. This will help you become comfortable with your words so that they don’t come out stilted while presenting. It is also important to emphasize vocal variety by changing the tone and intensity of your voice to keep the audience’s focus; boring monotone voices are often difficult to listen to. Remember to slow down or speed up depending on the importance of what you’re saying; never read word-for-word from your script – instead, aim for an engaging, conversational delivery. When delivering a manuscript speech, hand gestures can prove particularly useful for emphasizing key points. You can use arm movements and body language to convey the emotions behind your words without them feeling forced or unnatural. Again, practice helps here as well; make yourself aware of your posture and make subtle adjustments throughout until you feel comfortable speaking while moving around confidently on stage. Eye contact is another key element of effective presentation . Make sure to look into the eyes of every member of your audience at least once during your presentation – this will help them feel like they are interacting with you directly and make them more receptive to your ideas. Feel free to break away from traditional powerpoint slides if they aren’t necessary – take advantage of the natural lighting in the room and navigate through the visible space instead. Finally, remember that how you conclude the speech is just as important as how you began it, so aim for a powerful ending that leaves those listening with a lasting impression of what was discussed and learned throughout your presentation. With these tips for delivery in mind, you’re almost ready to leave a lasting impression on your audience – something we’ll discuss further in the next section!

Making a Lasting Impression with Your Audience

When you first create your manuscript speech, it is of utmost importance to consider your audience. Each part of the speech must be tailored to the people who will be listening. If a speaker can connect with an audience and make an emotional impact, the work that went into crafting the document will pay off. Using a conversational tone, humor, storytelling, and analogies can help keep the audience engaged during your speech. These techniques give the listener something to connect with and remember after the presentation is over. However, be sure to balance any humorous anecdotes or stories with a professional demeanor as not to lose credibility with your audience. Considering each part of the message and its potential impression on the listeners can also help guide you in tailoring a manuscript speech. When introducing yourself, try to use language that connects with the background of your peers; focus on wanting to help others with what you have learned or experienced so they feel like you are truly talking directly to them. Conclude by summing up important points in an inspirational way and leave listeners motivated and determined to apply the advice given in their own lives. Through this manner of “closing out” an effective speech, the audience can carry away meaningful information that will stay with them long after you finish speaking. Now that you understand how essential it is for speakers to make a lasting impression on their audiences, let us move onto learning how to confidently handle questions from your listeners as part of your presentation.

How to Handle Questions from Your Audience

When writing a manuscript speech, there are certain things you should consider when handling questions from your audience. This is an essential part of giving a successful talk to a group of people. The best way to handle questions is to take notes and make sure you can answer them directly after the speech is completed. It is important to be prepared with responses to any potential questions that may arise during your presentation. This will show your audience that you have taken the time and effort towards understanding their concerns and addressing them accordingly.

Additionally, it is also beneficial to anticipate possible areas of criticism or disagreement among members of your audience, as this allows you to provide evidence or offer an alternate route for them to consider when questioning the points made in your presentation. It is also important to remain courteous and professional when answering questions , even if someone challenges your views or speaks unkindly about your topic. It is always best practice to remain composed and ensure everyone in the room feels respected. Furthermore, having an open discussion with your audience following a well-prepared manuscript speech can add value by expanding on topics outlined. It also presents an opportunity for further clarifications and understanding beyond just getting out the message. This can be done by asking the participants what they thought of the presentation, what points they found most interesting, and other general feedback they might offer. If handled correctly, these moments can be used as learning opportunities for both yourself and others. Ultimately, handling questions from your audience confidently and gracefully is an important component of delivering a successful manuscript speech. By taking the time to prepare a response tailored towards each inquiry, even if it involves debate, you show respect towards those who took their time out of their day to attend your talk.

Additionally, it presents an opportunity to expand on topics covered while allowing meaningful dialogue between participants. With that said, it’s now time turn our focus onto crafting an effective conclusion for our manuscripts speeches – one which can bring our ideas full circle and leave our audience with memorable words!

Conclusion and Overall Manuscript Speech Strategy

The conclusion of any speech is an important part of the process and should not be taken lightly. Regardless of the structure or content of the speech, the conclusion can help drive home the points you have made throughout your speech. It also serves to leave a lasting impression on the listener. The conclusion should not be too long or drawn-out, but it should be meaningful and relevant to your topic and overall message. When writing your conclusion, consider recapping some of the key points made in the body of your speech. This will help to reinforce those ideas that you want to stick with the listener most. Additionally, make sure to emphasize how what has been addressed in your speech translates into real-world solutions or recommendations. This can help ensure that you have conveyed an actionable and tangible impact with your speech. One way to approach crafting an effective manuscript for a speech is to take note of the overall theme or objective that you wish to convey. From there, think about how best to organize your information into manageable sections, ensuring that each one accurately reflects your main points from both a visual and verbal standpoint. Consider what visuals or other tools could be used to further illustrate or clarify any complex concepts brought up in the main body of your speech. Finally, be sure to craft an appropriate conclusion that brings together all of these points into a cohesive whole, leaving your listeners with powerful words that underscore the importance and significance of what you have said. Overall, successful manuscript speeches depend on clear and deliberate preparation. Spending time outlining, writing, and editing your speech will ensure that you are able to effectively communicate its message within a set timeframe and leave a lasting impact on those who heard it. By following this process carefully, you can craft manuscripts that will inform and inspire audiences while driving home key talking points effectively every time.

Frequently Asked Questions and Their Answers

What are the benefits of giving a manuscript speech.

Giving a manuscript speech has many benefits. First, it allows the speaker to deliver a well-researched and thought-out message that is generally consistent each time. Since the speaker has prepared their speech in advance, they can use rehearsals to perfect their delivery and make sure their message is clear and concise.

Additionally, having a manuscript allows the speaker the freedom to focus on engaging the audience instead of trying to remember what to say next. Having a written script also helps remove the fear of forgetting important points or getting sidetracked on tangents during the presentation. Finally, with a manuscript, it’s possible to easily modify content from performance to performance as needed. This can help ensure that every version of the speech remains as relevant, meaningful, and effective as possible for each audience.

How does one prepare a manuscript speech?

Preparing a manuscript speech requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are the five steps to help you write a successful manuscript speech: 1. Research: Take the time to do your research and gather all the facts you need. This should be done well in advance so that you can prepare your speech carefully. 2. Outline: Lay out an outline of the major points you want to make in your speech and make sure each point builds logically on the one preceding it. 3. Draft: Once you have an outline, begin to flesh it out into a first draft of your manuscript speech. Be sure to include transitions between key points as well as fleshing out any examples or anecdotes that may help illustrate your points. 4. Edit: Once you have a first draft, edit it down multiple times. This isn’t where detailed editing comes in; this is more about making sure all the big picture elements work logically together, ensuring smooth transitions between ideas, and ensuring your words are chosen precisely to best convey their meaning. 5. Practice: The last step is perhaps the most important – practice! Rehearse your manuscript speech until you know it like the back of your hand, so that when it’s time for delivery, you can be confident of success.

What are some tips for delivering a successful manuscript speech?

1. Prepare in advance: Draft a script and practice it several times before delivering it. This will allow you to be comfortable with your material and avoid any awkward pauses when you are presenting your speech. 2. Speak clearly: Make sure that you speak loudly and clearly enough for everyone in the room to hear you. It is also important to enunciate your words properly so that your message can easily be understood by your audience. 3. Engage with the audience: Use eye contact when addressing your audience, ask questions and wait for responses, and pause to allow people time to mull over your points. These techniques help to ensure that everyone is engaged and interested in what you are saying. 4. Create visual aids: Create slides or other visuals that augment the material in your manuscript speech. This can help to keep the audience focused on what they are hearing as well as providing a reference point for them after your speech is finished. 5. Rehearse: Rehearse the delivery of your manuscript speech at least once prior to giving it so that you feel confident about how it will sound when presented in front of an audience. Identify any areas where improvements may be needed and focus on perfecting them before delivering the speech.

How to Write a Manuscript for a Speech

Feeling behind on ai.

You're not alone. The Neuron is a daily AI newsletter that tracks the latest AI trends and tools you need to know. Join 250,000+ professionals from top companies like Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce and more. 100% FREE.

Being asked to deliver a speech can be both an exciting and nerve-wracking experience. Whether it's a speech for a conference, a public speaking event, or a special occasion, it's vital to have a well-written manuscript that will effectively communicate your message to your audience and leave a lasting impression. In this article, we will guide you through the essential steps of how to write a manuscript for a speech, from understanding the purpose of your speech to delivering a memorable conclusion.

Understanding the Purpose of a Speech Manuscript

Before you start writing your speech manuscript, it's crucial to identify the purpose of your speech. There are three primary categories of speeches:

Informative Speeches

Informative speeches aim to educate the audience about a specific topic by providing relevant information. The purpose of an informative speech manuscript is not to persuade the audience but to convey essential information.

For example, if you are giving a speech about the history of the United States, your goal is to provide factual information about the country's past. You might discuss significant events, such as the American Revolution or the Civil Rights Movement, and how they shaped the country. You might also talk about key figures in American history, such as George Washington or Martin Luther King Jr.

When writing an informative speech manuscript, it's essential to consider your audience's level of knowledge about the topic. If your audience is already familiar with the subject, you might need to delve deeper into the topic to provide new and interesting information. If your audience is relatively unfamiliar with the subject, you might need to provide more background information to help them understand the topic better.

Persuasive Speeches

Persuasive speeches, as the name suggests, aim to persuade the audience to take a specific action or adopt a particular point of view. The purpose of a persuasive speech manuscript is to convince and influence the audience.

For example, if you are giving a speech about the importance of recycling, your goal is to persuade the audience to recycle more. You might discuss the environmental benefits of recycling, such as reducing waste and conserving natural resources. You might also talk about the economic benefits of recycling, such as creating jobs in the recycling industry.

When writing a persuasive speech manuscript, it's essential to consider your audience's beliefs and values. You need to understand their perspective on the topic and tailor your arguments accordingly. You might need to address common objections to your point of view and provide counterarguments to persuade your audience to see things your way.

Special Occasion Speeches

Special occasion speeches are usually delivered at specific public events such as weddings, funerals, or award ceremonies. The purpose of a special occasion speech manuscript is to commemorate and celebrate a particular event or person.

For example, if you are giving a speech at a wedding, your goal is to celebrate the love and commitment between the couple. You might talk about how the couple met, their shared interests and values, and how they complement each other. You might also offer advice for a happy and successful marriage.

When writing a special occasion speech manuscript, it's essential to consider the tone of the event. You need to strike the right balance between humor and sentimentality, depending on the occasion. You might also want to include personal anecdotes or stories to make the speech more engaging and memorable.

Researching and Gathering Information

Once you have identified the purpose of your speech manuscript, it's time to start researching and gathering information. The success of your speech depends on the quality and relevance of the information you present to your audience. Here are some essential tips for collecting relevant data:

Identifying Your Audience

The first step in gathering information for your speech manuscript is to identify your target audience. Knowing your audience demographic can help you shape your speech to fit their needs and interests.

For example, if you are giving a speech to a group of college students, you may want to focus on topics that are relevant to their age group and academic interests. On the other hand, if you are speaking to a group of professionals, you may want to focus on topics related to their industry or field of work.

By identifying your audience, you can tailor your speech to their specific needs and interests, making it more engaging and relevant to them.

Collecting Relevant Data

Collecting relevant data is critical to the success of your speech manuscript. Use reputable sources such as academic journals, news articles, and statistical data to support your speech's main points.

When researching your topic, it's important to consider both sides of the argument. This will help you present a balanced and well-informed speech that addresses all aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are giving a speech on the benefits of renewable energy, you may want to research both the advantages and disadvantages of renewable energy sources. This will allow you to present a more comprehensive and persuasive argument to your audience.

Citing Your Sources

When presenting information from external sources, it's essential to cite your sources correctly. Ensure that you use the appropriate citation format, such as MLA or APA, to avoid plagiarism and give credit to the original author.

Citing your sources also adds credibility to your speech and shows that you have done your research. It demonstrates that you have taken the time to gather relevant information from reputable sources and have used this information to support your arguments.

Overall, researching and gathering information is a crucial step in creating a successful speech manuscript. By identifying your audience, collecting relevant data, and citing your sources, you can create a well-informed and persuasive speech that engages and informs your audience.

Organizing Your Speech

After gathering and organizing your information, it's time to start writing your speech manuscript. Here are some essential tips for organizing your speech manuscript:

Crafting a Strong Introduction

The introduction is the most critical part of your speech manuscript. It's where you capture your audience's attention and establish your credibility as a speaker. Start with a hook, such as a personal anecdote or a thought-provoking question, then introduce your topic.

Developing the Body of Your Speech

The body of your speech manuscript should contain your main points and supporting evidence. Organize your main points in a logical order, such as chronological or topical, and ensure that they flow seamlessly from one point to the next.

Writing a Memorable Conclusion

The conclusion is your final opportunity to leave a lasting impression on your audience. Summarize your main points and leave your audience with a memorable closing statement, such as a call to action or a quote.

Tips for Writing an Effective Manuscript

Here are some essential tips for writing an effective speech manuscript:

Using Clear and Concise Language

Avoid using complex jargon or unfamiliar words. Use clear and concise language to ensure that your audience can easily understand your message.

Incorporating Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices, such as repetition and metaphors, can make your speech more engaging and memorable. Use them sparingly to avoid overwhelming your audience.

Balancing Facts and Emotions

While it's essential to present factual information, don't forget to infuse emotions into your speech manuscript. Emotions can help you connect with your audience and make your message more compelling.

By following these essential steps, you can write a compelling and effective speech manuscript that will engage and inspire your audience. Remember to practice your speech delivery and refine your manuscript until you feel confident and prepared to deliver your speech.

ChatGPT Prompt for Writing a Manuscript for a Speech

Use the following prompt in an AI chatbot . Below each prompt, be sure to provide additional details about your situation. These could be scratch notes, what you'd like to say or anything else that guides the AI model to write a certain way.

Please produce a comprehensive and detailed document that will serve as the script for a speech.

[ADD ADDITIONAL CONTEXT. CAN USE BULLET POINTS.]

You Might Also Like...

5 Ways of Delivering Speeches

Understanding Delivery Modes

In this chapter . . .

In this chapter, we will explore the three modes of speech delivery: impromptu, manuscript, and extemporaneous. Each offers unique advantages and potential challenges. An effective public speaker needs to be familiar with each style so they can use the most appropriate mode for any speech occasion.

In writing, there’s only one way of delivering the text: the printed word on a page. Public Speaking, however, gives you different ways to present your text. These are called the delivery modes , or simply, ways of delivering speeches. The three modes are impromptu delivery , manuscript delivery , and extemporaneous delivery . Each of these involves a different relationship between a speech text, on the one hand, and the spoken word, on the other. These are described in detail below.

Impromptu Delivery

Impromptu speaking is a short form speech given with little to no preparation. While being asked to stand in front of an audience and deliver an impromptu speech can be anxiety-producing, it’s important to remember that impromptu speaking is something most people do without thinking in their daily lives . If you introduce yourself to a group, answer an open-ended question, express an opinion, or tell a story, you’re using impromptu speaking skills. While impromptus can be stressful, the more you do it the easier it becomes.

Preparation for Impromptu Delivery

The difficulty of impromptu speaking is that there is no way to prepare, specifically, for that moment of public speaking. There are, however, some things you can do to stay ready in case you’re called upon to speak unrehearsed.

For one, make sure your speaking instruments (your voice and body) are warmed up, energized, and focused. It could be helpful to employ some of the actor warm-up techniques mentioned earlier as part of an everyday routine. If appropriate to the impromptu speaking situation, you could even ask to briefly step aside and warm yourself up so that you feel relaxed and prepared.

Furthermore, a good rule when brainstorming for an impromptu speech is that your first idea is your best. You can think about impromptu speaking like improvisation: use the “yes, and” rule and trust your instincts. You’ll likely not have time to fully map out the speech, so don’t be too hard on yourself to find the “perfect” thing to say. You should let your opinions and honest thoughts guide your speaking. While it’s easy to look back later and think of approaches you should have used, try to avoid this line of thinking and trust whatever you come up with in the moment.

Finally, as you prepare to speak, remind yourself what your purpose is for your speech. What is it that you hope to achieve by speaking? How do you hope your audience feels by the end? What information is most important to convey? Consider how you’ll end your speech. If you let your purpose guide you, and stay on topic throughout your speech, you’ll often find success.

Delivery of Impromptu Speeches

Here is a step-by-step guide that may be useful if you’re called upon to give an impromptu speech:

- Thank the person for inviting you to speak. Don’t make comments about being unprepared, called upon at the last moment, on the spot, or uneasy.

- Deliver your message, making your main point as briefly as you can while still covering it adequately and at a pace your listeners can follow.

- Stay on track. If you can, use a structure, using numbers if possible: “Two main reasons . . .” or “Three parts of our plan. . .” or “Two side effects of this drug. . .” Past, present, and future or East Coast, Midwest, and West Coast are common structures.

- Thank the person again for the opportunity to speak.

- Stop talking when you are finished (it’s easy to “ramble on” when you don’t have something prepared). If in front of an audience, don’t keep talking as you move back to your seat. Finish clearly and strong.

Impromptu speeches are most successful when they are brief and focus on a single point.

Another helpful framing technique for impromptus is to negate the premise. This is the deliberate reframing of a given prompt in a way that acknowledges the original but transitions into talking about the topic in a different way than expected. Negating the premise can be an effective rhetorical technique if used carefully and can help you focus your response on a topic that you’re interested in talking about.

If you suddenly run out of things to say in the middle of your speech, be open to pivoting . Giving another example or story is the easiest way to do this. What’s important is to not panic or allow yourself to ramble aimlessly. No matter what, remember to keep breathing.

Finally, the greatest key to success for improving impromptu speaking is practice. Practice speaking without rehearsal in low-stakes environments if you can (giving a toast at a family dinner, for example). But remember this: no one is expecting the “perfect” speech if you’re called upon to speak impromptu. It’s okay to mess up. As Steven Tyler of the rock band Aerosmith would say: dare to suck. Take a risk and make a bold choice. What is most important is to stay sure of yourself and your knowledge.

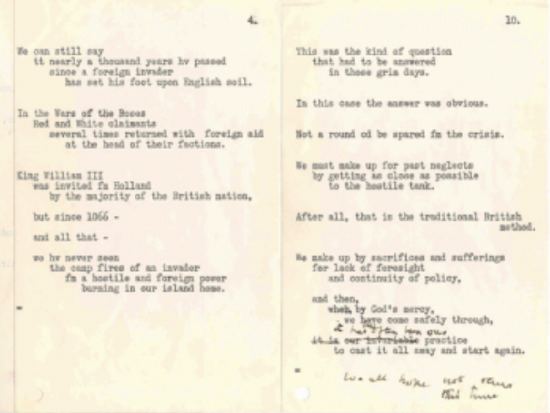

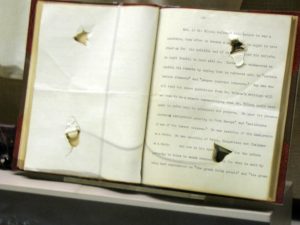

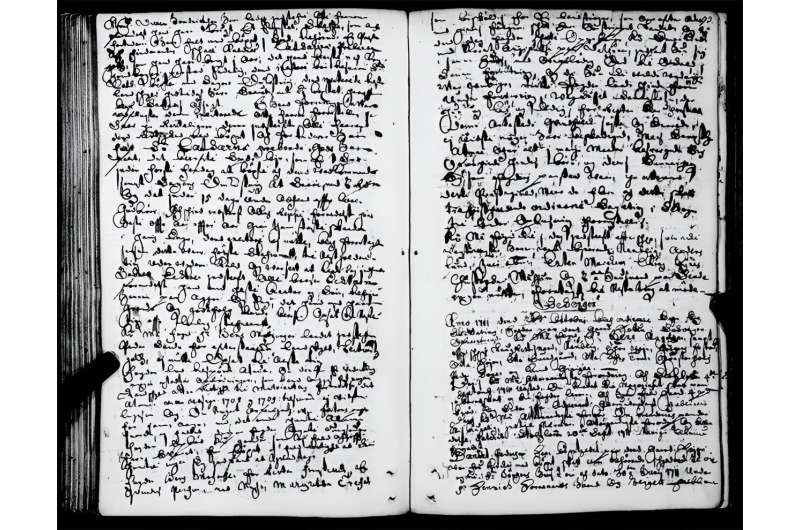

Manuscript Delivery

The opposite of an impromptu speech is the manuscript speech. This involves having the complete text of your speech written out on paper or on notecards. You may be reading the speech from a computer or a teleprompter. In some cases, the speaker memorizes this manuscript.

Manuscript delivery is the word-for-word iteration of a written message. In a manuscript speech, the speaker maintains their attention on the printed page except when using visual aids. The advantage of reading from a manuscript is the exact repetition of original words. In some circumstances, this can be extremely important.

Advantages & Disadvantages to Manuscript Delivery

There are many advantages in speaking from a manuscript. Some people find they are less nervous when they have the whole text in front of them. If you get lost or flustered during the speech you can glance down and get back on track. For speakers who struggle with vocalized pauses, it can be easier to know exactly what you want to say so that you’re not searching for the right word. Some people prefer to carefully craft the language of their speech instead of just having a sense of the main point and expounding upon it. Particularly if there are a lot of statistics or quotations, it can be helpful to have the whole passage written out to make sure you not only convey it correctly but frame it in the right context. It’s also easier to rehearse and time a manuscript speech, thus making sure it stays within time limits and isn’t unexpectedly too short or long. For some formal occasions or events that may be emotional for the speaker, such as a funeral, using a manuscript may be the best approach.

There are some disadvantages in delivering a speech from a manuscript. Having a manuscript in front of you often encourages looking down and reading the speech instead of performing it. A lack of eye contact makes the audience feel less engaged. The speech can feel stilted and lacking energy. Some speakers may feel constrained and that they can’t deviate from their script. Furthermore, while some find it easier to find their place with a quick glance down having the full manuscript, others find it difficult to avoid losing their place. If you go off script it can be harder to recover.

Successful Manuscript Delivery

A successful manuscript delivery requires a dynamic performance that includes lots of eye contact, animated vocals, and gestures. This can only be accomplished if you’re very familiar with the manuscript. Delivering a manuscript that you have written but only spoken aloud once before delivery will most often result in stumbling over words and eyes locked to the page. You’ll be reading aloud at your audience, instead of speaking to them. Remember what it’s like in school when a teacher asks a student to stand up and read something aloud? If the student isn’t familiar with the text, it can be a struggle both for the reader and the audience.

The key to avoiding this problem is to practice your written speech as much as you can, at least five or six times. You want to get so familiar with your speech that you can take your eyes off the page and make frequent eye contact with your audience. When you’re very familiar with your speech, your tone of speaking becomes more conversational. The text flows more smoothly and you begin to sound like a speaker, not a reader. You can enjoy the presentation and your audiences will enjoy it as well.

To improve your skills at manuscript delivery, practice reading written content aloud. This allows you to focus exclusively on delivery instead of worrying about writing a speech first. In particular, reading dialogue or passages from theatre plays, film/television scripts, or books provides material that is intended to be expressive and emotive. The goal is to deliver the content in a way that is accessible, interesting, alive, and engaging for the audience.

To Memorize or Not to Memorize

One way to overcome the problem of reading from the page is to memorize your word-for-word speech. When we see TED Talks, for example, they are usually memorized.

Memorized speaking is the delivery of a written message that the speaker has committed to memory. Actors, of course, recite from memory whenever they perform from a script. When it comes to speeches, memorization can be useful when the message needs to be exact, and the speaker doesn’t want to be confined by notes.

The advantage to memorization is that it enables the speaker to maintain eye contact with the audience throughout the speech. However, there are some real and potential costs. Obviously, memorizing a seven-minute speech takes a great deal of time and effort, and if you’re not used to memorizing, it’s difficult to pull off.

For strategies on how to successfully memorize a speech, refer to the “Memorization” section in the chapter “ From Page to Stage .”

Extemporaneous Delivery

Remember the fairy tale about Goldilocks and the Three Bears? One bed is too soft, the other bed is too hard, and finally one is just right? Extemporaneous delivery combines the best of impromptu and manuscript delivery. Like a manuscript speech, the content is very carefully prepared. However, instead of a word-for-word manuscript, the speaker delivers from a carefully crafted outline. Therefore, it has elements of impromptu delivery to it. We call this type of speaking extemporaneous ( the word comes from the Latin ex tempore, literally “out of time”).

Extemporaneous delivery is the presentation of a carefully planned and rehearsed speech, spoken in a conversational manner using brief notes. By using notes rather than a full manuscript, the extemporaneous speaker can establish and maintain eye contact with the audience and assess how well they understand the speech as it progresses. Without all the words on the page to read, you have little choice but to look up and make eye contact with your audience.

For an extemporaneous speech, the speaker uses a carefully prepared outline. We will discuss how to create an effective outline in the chapters on speechwriting.

Advantages & Disadvantages of Extemporaneous Delivery

Speaking extemporaneously has some major advantages. As mentioned above, without having a text to be beholden to it’s much easier to make eye contact and engage with your audience. Extemporaneous speaking also allows flexibility; you’re working from the solid foundation of an outline, but if you need to delete, add, or rephrase something at the last minute or to adapt to your audience, you can do so. Therefore, the audience is more likely to pay better attention to the message. Furthermore, it promotes the likelihood that you, the speaker, will be perceived as knowledgeable and credible since you know the speech well enough that you don’t need to read it. The outline also helps you be aware of main ideas vs. subordinate ones. For many speakers, an extemporaneous approach encourages them to feel more relaxed and to have more fun while speaking. If you’re enjoying presenting your speech the audience will sense that and consequently, they will enjoy it more.

A disadvantage of extemporaneous speaking is that it requires substantial rehearsal to achieve the verbal and nonverbal engagement that is required for a good speech. Adequate preparation can’t be achieved the day before you’re scheduled to speak. Be aware that if you want to present an engaging and credible extemporaneous speech, you’ll need to practice many times. Your practice will need to include both the performative elements as well as having a clear sense of the content you’ll cover. As mentioned previously, an extemporaneous speech can also be harder to have consistent and predictable timing. While delivering the speech it’s more likely you’ll wander off on a tangent, struggle to find the words you want, or forget to mention crucial details. Furthermore, if you get lost it may be harder to get yourself back on track.

Successful Extemporaneous Delivery

Like other delivery modes, a dynamic performance on an extemporaneous delivery is one that includes lots of eye contact, animated vocals, and gestures. At the same time, you want a speech that is structured and focused, not disorganized and wandering.

One strategy to succeed in extemporaneous speaking is to begin by writing out a full manuscript of your speech. This allows you to map out all the information that will be covered in each main point and sub-point. This method also gives you a better sense of your timing and flow than starting from just an outline. Another approach is to write out an outline that is less complete than a manuscript but still detailed. This will be used only for preparation; once you have a clear sense of the content you can reduce it down to a streamlined performance outline which you’ll use when delivering the actual speech.

By the time of presentation, an extemporaneous speech becomes a mixture of memorization and improvisation. You’ll need to be familiar enough with your content and structure that you cover everything, and it flows with logical transitions. Simultaneously, you must be willing to make changes and adapt in the moment. Hence, thorough rehearsal is critical. While this approach takes more time, the benefits are worth the extra effort required.

When you’re asked to prepare a speech for almost any occasion except last-minute speeches, you must choose either a manuscript or extemporaneous approach. As you experiment with assorted styles of public speaking, you’ll find you prefer one style of delivery over the other. Extemporaneous speaking can be challenging, especially for beginners, but it’s the preferred method of most experienced public speakers. However, the speaking occasion may dictate which method will be most effective.

Online Delivery

Impromptu, manuscript, and extemporaneous speaking are delivery modes . They describe the relationship between the speaker and the script according to the level of preparation (minutes or weeks) and type of preparation (manuscript or outline). Until now, we have assumed that the medium for the speech is in-person before an audience. Medium means the means or channel through which something is communicated. The written word is a medium. In art, sculpture is a medium. For in-person public speaking, the medium is the stage. For online public speaking, the medium is the camera.

The Online Medium

Public speakers very often communicate via live presentation. However, we also use the medium of recordings, shared through online technology. We see online or recorded speaking in many situations. A potential employer might ask for a short video self-presentation. Perhaps you’re recording a “How-To” video for YouTube. A professor asks you to create a presentation to post to the course website. Or perhaps an organization has solicited proposals via video. Maybe a friend who lives far away is getting married and those who can’t attend send a video toast. While this textbook can’t address all these situations, below are three important elements to executing recorded speeches.

Creating Your Delivery Document

As with an in-person speech, it’s important to consider all the given circumstances of the speech occasion. Why are you speaking? What is the topic? How much time do you have to prepare? How long is this speech? In online speeches, having a sense of your audience is critical. Not only who are they, but where are they? You may be speaking live to people across the country or around the world. If they are in a different time zone it may influence their ability to listen and respond, particularly if it’s early, late, or mealtime. If you’re recording a speech for a later audience, do you know who that audience will be?

As with in-person speeches, different speech circumstances suggest one of three delivery modes: impromptu, extemporaneous, or manuscript. Whether your medium is live or camera, to prepare you must know which of the three delivery modes you’ll be using. Just because a speech is online does not mean it doesn’t need preparation and a delivery text.

Technical Preparation

To prepare for online speaking, you’ll want to practice using your online tools. To begin, record yourself speaking so you have a sense of the way your voice sounds when mediated. Consider practicing making eye contact with your camera so that you feel comfortable with your desired focal point. In addition, consider how to best set up your speaking space. It may take some experimenting to find the best camera angle and position. Consider lighting when deciding your recording place. Make the lighting as bright as possible and ensure that the light is coming from behind the camera.

You should put some thought into what you’ll be wearing. You’ll want to look appropriate for the occasion. Make sure your outfit looks good on camera and doesn’t clash with your background. In general, keep in mind what your background will look like on-screen. You’ll want a background that isn’t overly distracting to viewers. Furthermore, ensure that there is a place just off-screen where you can have notes and anything else you may need readily at hand. Your recording location should be somewhere quiet and distraction-free.

You should test your camera and microphone to make sure they are working properly, and make sure you have a stable internet connection. But, even when you complete pre-checks of equipment, sometimes technology fails. Therefore, it’s helpful to know how to troubleshoot on the spot. Anticipate potential hiccups and have a plan for how to either fix issues that arise or continue with your presentation.

Vibrant Delivery

The tools for successful public speaking discussed in the rest of this textbook still apply to online speaking, but there are some key differences to consider before entering the virtual space. Online speaking, for example, will not have the same energy of a back-and-forth dialogue between speaker and live audience. If you’re recording without an audience, it might feel like you’re speaking into a void. You must use your power of imagination to keep in mind the audience who will eventually be watching your speech.

It’s important to utilize all your vocal tools, such as projection, enunciation, and vocal variety. Most important is having a high level of energy and enthusiasm reflected in your voice. If your voice communicates your passion for your speech topic, the audience will feel that and be more engaged. Use humor to keep your speech engaging and to raise your own energy level. Some experts recommend standing while giving an online speech because it helps raise your energy level and can better approximate the feeling of presenting in public.

If you’re presenting online to an audience, be sure to start the presentation on time. However, be aware that some participants may sign in late. Likewise, be cognizant about finishing your speech and answering any questions by the scheduled end time. If there are still questions you can direct the audience to reach out to you by your preferred means of communication. You may be able to provide the audience with a recording of the talk in case they want to go back and rewatch something.

Finally, consider ways you can enhance your performance by sharing images on the screen. Be sure you have that technology ready.

Other suggestions from experts include:

- Your anxiety does not go away just because you can’t see everyone in your “web audience.” Be aware of the likelihood of anxiety; it might not hit until you’re “on air.”

- During the question-and-answer period, some participants will question orally through the webcam set-up, while others will use the chat feature. It takes time to type in the chat. Be prepared for pauses.

- Remember the power of transitions. The speaker needs to tie the messages of their slides together.

- Verbal pauses can be helpful. Since one of the things that put audiences to sleep is the continual, non-stop flow of words, a pause can get attention.

As you begin delivering more public speeches you will likely find a preference for one or more of these delivery modes. If you are given a choice, it’s often best to lean into your strengths and to utilize the method you feel most comfortable with. However, the speech occasion may dictate your presentation style. Therefore, it’s important to practice and become comfortable with each mode. In an increasingly technological world online speaking in particular is likely going to be a required method of communication.

Media Attributions

- Delivery Modes and Delivery Document © Mechele Leon is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

First Time Authors-Here's The Key To Getting Published

Free tips and resources for first time authors looking for publishing deals.

Subscribe via Email

How To Write A Manuscript For A Speech

Public speaking can fill one with a sense of dread, but knowing how to write a manuscript for a speech can make the difference between a successful speaking engagement and one that is not. Many factors should be considered when preparing a speech.

Preparing an outline is always helpful; make headings that clearly make key points and fill in the facts that are to be presented under each heading. Consider the phrasing of the headlines as they can be directly used as the introductory sentences to your points.

Knowing the key target audience is the most important factor in writing the manuscript. Avoid speaking over them; a group of highschool kids will need to be addressed in a different way than a roomful of adults. Keep the tone of the speech inline with the target audience. Lightheartedness may not be an appropriate tone for all occassions, but this approach is perfect for a younger audience.

Knowing how to write a manuscript for a speech sounds like an overwhelming task, but backing up the outline with well researched information keeps the manuscript interesting. When doing fact based research, try to find a new angle for the information. A speech on the deadly effects of carbon monoxide in and of itself, for instance, could be boring to listeners who already know that this is a deadly exposure. Liven the speech up with unusual facts as well, such as that in the 1800’s through the 1900’s carbon monoxide released through gas lamps accounted for sightings of ghosts and other hallucinations, and that Edgar Allen Poe is thought to have been suffering the effects of chronic carbon monoxide poisoning while writing his works. These facts would be a pertinent, entertaining and unusual way to grab audience attention. Be sure any facts offered are well researched and accurate, but do not drag the audience attention down with citing continued fact references. Terms such as “research shows” or “it has been found that” are often a better lead up to your facts and continue to keep audience attention.

Remember when writing the speech that the amount of time taken to prepare it is often far short of the amount of time it will take to deliver it. It is better to prepare the manuscript to be longer and pare it down than to consider it finished and have to add material. Using the method of paring down rather than adding on allows the ideas to flow freely, whereas adding material can often result in a speech that sounds choppy.

Once the manuscript is written, preparing to deliver it can be done at first in front of a mirror and then in front of family and friends. These practice sessions do more than boost confidence, they allow the speaker to practice inflection and emphasis. Some ideas can be changed at this point since some things sound better in writing than they do spoken aloud.

my tribute speech on barack obama? so for my english class we have to do a tribute speech on someone we look up to and first i chose my mom then i changed it to my dad then i changed it to obama can anyone help me write my tribute speech? or help me with some ideas this is what it has to have…

Step 1 (Investigate/Decide) – 250 words; due Thursday, January 8 Yes, you have to do this step, so stop whining. Reflect on a significant personality who has had an impact on our world, or who has personally influenced you. oWhy do you look up to this person? What do you consider worthy of tribute about him/her? oList his/her admirable traits oCreate a list of 5 to 10 interview questions that you would ask this person if given the opportunity to interview him or her. Consider using words and phrases such as: justify, explain, evaluate, “to what extent”, classify, describe, determine, implement, defend, etc. (See list of possible words to use in formulating a question) oIf you had an opportunity to thank this person, what would you thank him/her for?

Step Two: (Investigate/Research continues) – due with step 3 Now that you’ve chosen your subject, investigate and record on paper the answers to the following bulleted questions/statements

oBiography –origins (background, family life, education, etc) oTimeline – highlight accomplishments oRelevancy- just what is it that makes your subject worthy of this tribute speech? oUse library and Internet as needed (you must have at least 6 sources for this speech. If your speech is about a famous person, you must make sure they are accurate…keep track of them on work-cited page. If your speech is about a person who is not famous, then you must use interviews, old local newspaper articles, old family albums, etc.)

Step Three: Plan and Decide (Create Outline of Speech) – due Thursday, January 15 Decide which information you will use from your research. Plan the best way to organize your information into an effective speech.

Create an outline of your speech (please put details on the outline) Example of how you might organize speech: oQuote or eye-opening fact; statistic; etc…hook oBiography of Individual oAccomplishments oWhy tribute to this individual?

**Step Four: Create Full Written Draft of Speech – Due Tuesday, January 20 Create your manuscript with an introduction, body, and conclusion. Include the stylistic devices listed for objective #5. Cite sources within your manuscript as appropriate using MLA format. You will need a Work Cited page as well. Peer Edit and Revision

Step Five •Rehearse—create note cards and time yourself. •Did you remember to cite sources and create your work cited page?

Step Six: Presentation of Speeches with Peer Evaluation/Turn in Manuscript. All Speeches due Tuesday, January 20 whether it is your day to present or not! Keep a copy for yourself! Present and Evaluate Speeches (4 to 6 minutes)

and this is what i have so far:

January 21, 2009 English 10

Barack Obama was born August 4, 1961. Honolulu , Hawaii , USA . His full name is Barack Hussein Obama Jr.; which means “Blessed by God”, in Arabic He was born to a white American mother, Ann Dunham. And a black father, Barack Obama, Sr. they both were students at the University of Hawaii . His father left to Harvard while his wife and son stayed behind. His father went back to Kenya where he worked as an economist. Barack’s mother remarried an Indonesian. He worked as an oil manager. His father would write to him, but due to his business, he visited his son only once, and that was when Barack was ten. Barack managed to go to one of Hawaii ’s top prep academy, which is Punahou School . Then later on Barack attended Columbia University . He became a community organizer for a small Chicago church for three years. He helped poor south side people deal with a wave of plant closing. Then he attended Harvard Law School . In 1990 he became the first African-American editor of the Harvard Law Review. Then in Chicago he practiced civil-rights law. In 2004 Barack Obama was elected to the U.S senate as a Demarcate representing Illinois . Then in November, 2008 he ran for president as a democrat and won! And now he is the 44th president of the United States and the first African- American running for president. Barack Obama’s greatest accomplishment is his family, His two daughters and wife. He is worthy of my tribute speech because he is the very brave and he is the first African- American president. And because he is Step One- investigate/design I look up to this person because he has done many good things.

It’s good. Maybe find a way to replace pathos a couple times (them) towards the beginning of your essay. On the part where you say “if the paper were to be written on…” you should take out “than” after the comma. When you list the reasons why Golding might be better, I would say “he” instead of just Golding. Change “It is understandable that some people may think that Golding is more effective in his paper than Clark. Golding is older, Golding has more education, and Golding more experience in college, than Clark does. Many people may argue that Golding has the better paper, due to the previously listed reasons, and those reasons are understandable” to “Understandably, people will argue that Golding is superior to Clark when it comes to writing effectively. They will stress that Golding has experience on his side due to age and more college education.” Change “Something that may be agreeable though, is that Golding may have the better paper when it comes to following the rules of writing, and his organization style; but that Clark’s paper is actually better because he is in college, and that this paper is directed mainly towards current college students.” To “Something that may be agreeable, though, is that Golding has the better paper when it comes to the formalities of writing and organization, yet Clark’s paper is actually more meaningful due to the fact that he can relate to his target audience – he is in college, too.”

Sorry, but I’m too tired to continue. I didn’t study your essay much, so I’m not sure how well my edits would flow, but I tried. Also, there a couple of words that you should use a thesaurus on – I advise if it appears 3 or more times to do it.

It was a great essay and you can always go back to your original if you don’t like mine (but there were a few comma, etc. problems).

GOOD LUCK!!!

ENGLISH PAPER PART 2 PLEASE PROVIDE INPUT AND HELP? How many people want to be deprived of freedoms? One could assume that the majority of the United States citizens support freedom, so one could see how this idea may anger people. Pathos is a very effective way to get people to understand a view, and Clark does a great job of using it. In Golding’s article, he still uses Pathos, but to a much lesser extent. He uses pathos in some of his examples, and it is effective when it is used. Although he uses pathos a little bit in his article, for the most part he seems to simply argue and discuss the topics. By doing this he makes the reader less willing to read on, thus making his article less effective overall. Clark also is at an advantage because he is a college student, and these writings are more directed at college students than anyone else. Golding cannot control the fact that he is a professor, but it does put him at a disadvantage. Clark was a college student when he wrote this, so he knew how students his age interpreted things, Golding was from a different generation than the intended audience, and the ways of thinking among college student changed since Golding was in college. When Clark wrote this essay, one may assume that he talked to his college aged friends about this topic, and asked them what they think; Assuming that Clark did this, it helped him to be more successful in his paper than Golding. If the paper were to be written solely on free speech among college professors, than Golding would probably have the advantage of better understanding the intended audience better. It is understandable that some people may think that Golding is more effective in his paper than Clark. Golding is older, Golding has more education, and Golding more experience in college, than Clark does. Many people may argue that Golding has the better paper, due to the previously listed reasons, and those reasons are understandable. Something that may be agreeable though, is that Golding may have the better paper when it comes to following the rules of writing, and his organization style; but that Clark’s paper is actually better because he is in college, and that this paper is directed mainly towards current college students. It is also understandable that the ways of teaching how to write papers has changed, and how students are educated has changed, so due to these reasons Clark’s paper may actually be more current and apply more to it’s intended audience than Golding’s. Clark’s paper is a well written paper, and due to his use of straightforwardness, pathos, simplicity in his writing, and his advantage due to his age, he may still have the better piece of writing, even if Golding is more educated and more intelligent.

Sources Golding, M. P. (2000). Campus Speech Issues. Manuscript in preparation. Clark, Q. Speech Codes: An Insult to Education and a Threat to Our Future.

First of all, “Sir” Isaac Newton never served in Parliament. He served in 1698 and in 1701-02, but he wasn’t knighted until 1705. If the knighthood gave him the wherewithal to hire an assistant, that helper could not have written a Parliamentary speech with him. Second, Newton never argued before the House of Lords: he represented his university, Cambridge, in the House of Commons. Third, Newton’s only recorded words in Parliament were a point of order, a request to close a drafty window. He never made a “maiden speech”, nor argued for any bill. To top it all off, his service and knighthood had nothing to do with his scientific work. James II tried to turn the universities into Catholic institutions; Newton (and Cambridge itself) staunchly opposed the idea. Newton simply voted that way at every opportunity. The Queen so appreciated his efforts in support of this and other of her political causes that she knighted him.

After explaining the problems to the embarrassed vendor, Nora bought the document for £13, just as a reminder that she doesn’t know it all. She eventually got it identified: a portion of an unfinished play by a minor author, circa 1870.

She Turned Me Into a Newton!? After identifying a suspicious fellow Yankee at the local pub, Nora Shekrie decided to take a holiday at the market in Blyth. She was escorted by her not-too-distant relatives, Sir Loine of Boef and Lady Rose Boef. Nora wanted to take home some memento of her visit, something more than the prepaid travel vouchers Sir Harold had supplied. After a morning of making nice with the locals, receiving thanks, admiration, and not a few jibes about being from “the Colonies”, Nora was quite enjoying herself. The morning tea and late lunch were taking up a serene position in her abdomen, the sun was shining, and the studied quaintness of the market enchanted her more with each passing hour. She politely examined each stall of wares, commented astutely on some aspect of almost every shop, and generally impressed the vendors as something rather better than the stereotypical American tourist. Finally, at half-past two o’clock, she found the item to take home. An youngish gentleman selling out-of-print books had an item that intrigued her.

“It’s the manuscript of an early draft of the speech,” he explained as she bent over to examine the fine penmanship. “One of my ancestors was an assistant to Sir Isaac Newton. He served in Parliament, you know.” Nora nodded. “Dodgy times, what with the Glorious Revolution and all, but my many-greats grandfather found a stable position with Sir Isaac, right after the knighthood gave him enough money to hire someone permanent-like. Sir Isaac asked G-g-g-grandfather, Thomas Hanscomb was his name, to write some for his first speech in the House of Lords. Oh, Newton supplied the ideas sure enough, but Hanscomb did the first bit of writing, not what many could write back then. “Newton took Hanscomb’s draft, did it up his own way, no surprise to either of them I warrant, and gave back the first. That’s it, there in the frame and protective glass and all, and I keep it out of the sun like you see here.” The three of them noted the shade over the one item, giving it further protection from the light. “Sir Isaac made his grand speech, both houses passed whatever bill, and Thomas Hanscomb stuffed this copy into his things. It come down to me after all this time.” Nora nodded, seeming to have reached some decision. “And it’s certainly dear enough,” she held up a hand to stop him, “but fairly, given its history. Across the pond, a representative’s first speech in Congress is considered a great event.” She considered her bank balance, held a mental argument with herself, and pulled out her billfold. “I take traveler’s cheques, VISA, and cash,” he smiled. Nora smiled in return, pulling out a small plastic card. She felt a polite tug at her sleeve: Rose. ” For a purchase this significant, I usually like to get my mind well settled before I sign the papers, just to be sure. Shall we have a cuppa, and you talk to me about this?” There was a note in Rose’s voice; Nora had learned to respect that tone over her ten days with the family. She turned to the stall-keeper. “Would a fiver hold it for an hour?” “M’lady, at this price, a scone would hold it for the day.” Nora grinned. “A scone, it is. With jam?” He nodded. They had a deal.

They chose their table and allowed Harold to seat them with their food. He trundled back to the stalls with the extra scone, leaving his wife and guest to discuss the matter. “Rose, it sounds like I got off cheaply. You certainly know your business. Care to let me in on the secret? I’m usually the one who spots these things.”

How did Rose know that Nora shouldn’t buy the manuscript?

Is this paper good? What could I do to improve it? Part 2? How many people want to be deprived of freedoms? One could assume that the majority of the United States citizens support freedom, so one could see how this idea may anger people. Pathos is a very effective way to get people to understand a view, and Clark does a great job of using it. In Golding’s article, he still uses Pathos, but to a much lesser extent. He uses pathos in some of his examples, and it is effective when it is used. Although he uses pathos a little bit in his article, for the most part he seems to simply argue and discuss the topics. By doing this he makes the reader less willing to read on, thus making his article less effective overall. Clark also is at an advantage because he is a college student, and these writings are more directed at college students than anyone else. Golding cannot control the fact that he is a professor, but it does put him at a disadvantage. Clark was a college student when he wrote this, so he knew how students his age interpreted things, Golding was from a different generation than the intended audience, and the ways of thinking among college student changed since Golding was in college. When Clark wrote this essay, one may assume that he talked to his college aged friends about this topic, and asked them what they think; Assuming that Clark did this, it helped him to be more successful in his paper than Golding. If the paper were to be written solely on free speech among college professors, than Golding would probably have the advantage of better understanding the intended audience better. It is understandable that some people may think that Golding is more effective in his paper than Clark. Golding is older, Golding has more education, and Golding more experience in college, than Clark does. Many people may argue that Golding has the better paper, due to the previously listed reasons, and those reasons are understandable. Something that may be agreeable though, is that Golding may have the better paper when it comes to following the rules of writing, and his organization style; but that Clark’s paper is actually better because he is in college, and that this paper is directed mainly towards current college students. It is also understandable that the ways of teaching how to write papers has changed, and how students are educated has changed, so due to these reasons Clark’s paper may actually be more current and apply more to it’s intended audience than Golding’s. Clark’s paper is a well written paper, and due to his use of straightforwardness, pathos, simplicity in his writing, and his advantage due to his age, he may still have the better piece of writing, even if Golding is more educated and more intelligent.

Leave a Reply

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

About my blog

Glad you stopped by! Don't forget to sign up on the email list so you can get a free writing guide!

Recent Posts

- Effective Tips On Discovering the Best Book Publishing Companies In Chicago

- Literary Agents In Michigan

- Literary Agents In Minnesota

- Literary Agents In Missouri

- Literary Agents Mystery Fiction

- Young Adult Literary Agents Uk

- Literary Agents Los Angeles Nonfiction

Recent Comments

- Uncategorized

- September 2016

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

Powered by Flexibility 3

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Social Mettle

Manuscript Speech: Definition, Examples, and Presentation Tips

A manuscript speech implies reading a pre-written speech word by word. Go through this SocialMettle write-up to find out its meaning, some examples, along with useful tips on how to present a manuscript speech.

Tip! While preparing the manuscript, consider who your audience is, so as to make it effectual.

Making a speech comes to us as a ‘task’ sometimes. Be it in school, for a meeting, or at a function; unless you are at ease with public speaking, speeches may not be everyone’s cup of tea. A flawless and well-structured delivery is always welcome though. Memories of delivering and listening to a variety of speeches are refreshed when confronted with preparing for one.

Being the most effective way of communication, a speech is also a powerful medium of addressing controversial issues in a peaceful manner. There are four types of speeches: impromptu, extemporaneous, manuscript, and memorized. Each has its purpose, style, and utility. We have definitely heard all of them, but may not be able to easily differentiate between them. Let’s understand what the manuscript type is actually like.

Definition of Manuscript Speech

This is when a speaker reads a pre-written speech word by word to an audience.

It is when an already prepared script is read verbatim. The speaker makes the entire speech by referring to the printed document, or as seen on the teleprompter. It is basically an easy method of oral communication.

Manuscript speaking is generally employed during official meetings, conferences, and in instances where the subject matter of the speech needs to be recorded. It is used especially when there is time constraint, and the content of the talk is of prime importance. Conveying precise and succinct messages is the inherent purpose of this speech. Public officials speaking at conferences, and their speech being telecast, is a pertinent example.

There can be various occasions where this style of speech is used. It depends on the context of the address, the purpose of communication, the target audience, and the intended impact of the speech. Even if it is understood to be a verbatim, manuscript speaking requires immense effort on the part of the speaker. Precision in the delivery comes not just with exact reading of the text, but with a complete understanding of the content, and the aim of the talk. We have witnessed this through many examples of eloquence, like the ones listed below.

- A speech given by a Congressman on a legislative bill under consideration.

- A report read out by a Chief Engineer at an Annual General Meeting.

- A President’s or Prime Minister’s address to the Parliament of a foreign nation.

- A televised news report (given using a teleprompter) seen on television.

- A speech given at a wedding by a best man, or during a funeral.

- A religious proclamation issued by any religious leader.

- A speech in honor of a well-known and revered person.

- Oral report of a given chapter in American history, presented as a high school assignment.

Advantages and Disadvantages

✔ Precision in the text or the speech helps catch the focus of the audience.

✔ It proves very effective when you have to put forth an important point in less time.

✔ Concise and accurate information is conveyed, especially when talking about contentious issues.

✘ If you are not clear in your speech and cannot read out well, it may not attract any attention of the audience.

✘ As compared to a direct speech, in a manuscript that is read, the natural flow of the speaker is lost. So is the relaxed, enthusiastic, interactive, and expressive tone of the speech lost.

✘ A manuscript speech can become boring if read out plainly, without any effort of non-verbal communication with the audience.

Tips for an Appealing Manuscript Speech

❶ Use a light pastel paper in place of white paper to lessen the glare from lights.

❷ Make sure that the printed or written speech is in a bigger font size than normal, so that you can comfortably see what you are reading, which would naturally keep you calm.

❸ Mark the pauses in your speech with a slash, and highlight the important points.

❹ You can even increase the spacing between words for easier reading (by double or triple spacing the text).

❺ Highlight in bold the first word of a new section or first sentence of a paragraph to help you find the correct line faster.

❻ Don’t try to memorize the text, highlights, or the pauses. Let it come in the flow of things.