Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Literacy Narratives: Overview

“What is Your Story?” Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash “A word after a word after a word is power.”

— Margaret Atwood, author of The Handmaid’s Tale

Maybe you aren’t someone who writes much at all. Perhaps you don’t believe that there is really much purpose to writing. However, as a human being, you are, by your very nature, enthralled to the power of narrative. Stories shape the realities that we experience on a daily basis and on every level imaginable. Everything that you know or experience has been conveyed to you as a narrative of some sort, and you, in turn, depend on narrative to tell your story to the world. These narratives and the situations that they inhabit can be simple and commonplace–like you telling a parent or sibling about how your day went, from the difficulties that you faced to the good moments that kept you going. They can also be complex and unique–such as listening to a source that you trust and respect talk about what you should aspire to in life and what compromises you should and shouldn’t be willing to make along the way. Regardless, words and the stories in which they are enmeshed carry immense power, and they surround you in more ways that you might imagine.

This idea runs counter to common stereotypes of the literacy of our contemporary moment (or lack thereof). Phrases like “no one reads or writes anymore” are thrown about as if they are an unquestionable truth, but reality is another matter. In a landmark study of student writing habits at Stanford University in 2001, noted scholar Andrea Lunsford and colleagues discovered that their students were writing constantly and in an unimaginable range of environments: “These students did plenty of emailing, and texting; they were online a good part of every day; they joined social networking sites enthusiastically” ( “Our Semi-literate Youth?” ). Furthermore, these digital writing habits, rather than producing a shallower form of writing and reading comprehension, as many might assume, were “help[ing] them develop a range or repertoire of writing styles, tones, and formats along with a range of abilities” ( “Our Semi-literate Youth?” ). Writing and reading, then, are activities that happen all the time–even if their form has changed markedly during the past few decades.

Literacy narratives offer you an opportunity to reflect back on your own journey as a writer and reader, whether in a traditional or digital context. Perhaps most importantly, in revisiting your path up to this point and where you see the journey taking you into the future, you can gain a sort of perspective and agency that often isn’t possible in the moment. And, as this semester unfurls and your writing and reading abilities improve, you will, as Atwood indicates, gain increased power–both over the narratives that you author and put out into the world as well as those that you receive and which seek to gain your attention on behalf of their author. Such an author may be an individual very much like yourself or a corporation interested in convincing you to use one of their products. Regardless, your ability to engage, analyze, and respond to these outside narratives will give you increased agency in a world in which the number of narratives and authors are increasing exponentially. The literacy narrative assignment will provide an initial inroad for you on this path.

Everything is a Text!

The foundation of this course is built on your ability to read closely and critically. To engage with this skill, and the multiple literacies we navigate on a daily basis, this first major essay is a personal piece in which you will explore a significant moment regarding your own literacy; you may approach literacy either in the traditional sense or using our expanded, modern definition.

As you move through this chapter and related course resources, remember that a “text” in the context of this assignment, and in twenty-first-century composition studies in general, is anything that conveys a narrative to you–regardless of the medium. This, then, can be a book, a song, a social media site, a film, a video game, anything at all. As philosopher Jacques Derrida famously said, “Everything is a text.” In this sense, writing about your experience creating art or making music would fall under the purview of a “literacy narrative.” When you think through the essay that you would like to create below, make sure that you choose a topic that is authentic to your own experience, your own journey, and, perhaps most importantly, something that you are interested in continuing to explore through writing and reflection.

Use the following content, which has been adapted from Leslie Davis and Kiley Miller’s First-Year Composition, to plan your literacy narrative assignment.

ASSIGNMENT SHEET

Assignment Sheet – Literacy Narrative

Literacy is a key component of academic success, as well as professional success. In this class and others, you will be asked to read and engage with various types of texts, so the purpose of this assignment is twofold. First, this assignment will allow you to write about something important to you, using an open form and personal tone instead of an academic one, allowing you to examine some of your deepest convictions and experiences and convey these ideas in a compelling way through writing. Second, this essay provides us an opportunity to get to know each other as a class community.

For this assignment, you should imagine your audience to be an academic audience. Your audience will want a good understanding of your literacy, past, present, or future, and how you seek to comprehend the texts around you.

Requirements:

Choose ONE prompt below to tell about an important time in your life when you engaged with or were confronted with literacy, using the traditional or broad definition. We’ll discuss various types of literacy, so you will identify and define the type of literacy you’re discussing.

- Describe a situation when you were challenged in your reading or experience with a text (a book, song, film, etc.) by describing the source of that challenge (vocabulary, length, organization, content, something else). How did you overcome that challenge to understand what the text was saying? What strategies or steps do you plan to take in the future to make the process easier?

- Describe the type of texts you read (watch, listen to, play, etc.) most often. These texts can occur in traditional formal contexts or in the most informal situations (like group text message threads with your friends or posting on specific social media sites). What makes them easy or challenging to read and interpret? What strategies do you use to ensure that you fully understand them or can apply them in some form of productive context? How have they shaped you as a person?

- Describe your preferred mode of expressing yourself and communicating with the world. This, again, can be something more traditional like poetry, creating art, making music, or something more contemporary, like producing TikTok videos or curating an Instagram channel. It can even be something like cooking, playing a sport, or any other hobby or activity that gives unity, order, and meaning to your world. What have been some of the challenges that you faced as you learned how to create these types of texts? What have been some of your most memorable moments, and how has this mode of expression shaped you as an individual?

Formatting:

- Your professor will determine the exact length of this assignment, but a typical length for an essay of this sort is 1,000 words.

- Your work must be typed in size 12, Times New Roman font and double spaced, 1” margins, following MLA requirements.

Important Note About Topic Choice:

The format of this assignment provides you with quite a bit of leeway. Make sure that you choose your topic carefully. If you write about something that you are not interested in, you will have no one to blame but yourself.

Section One: Rhetoric and Personal Narrative

The foundation of our course is built on your ability to read closely and critically. To engage with this skill, and the multiple literacies we navigate on a daily basis, this project is a personal piece in which you will explore a significant moment regarding your own literacy; you may approach literacy either in the traditional sense or using our expanded, modern definition.

Exploring Literacy

What comes to mind when you hear the term “literacy”? Traditionally, we can define literacy as the ability to read and write. To be literate is to be a reader and writer. More broadly, this term has come to be used in other fields and specialties and refers generally to an ability or competency.

For example, you could refer to music literacy as the ability to read and write music; there are varying levels of literacy, so while you may recognize the image below as a music staff and the symbols for musical notes, it’s another thing to name the notes, to play any or multiple instruments, or to compose music.

Or, you may be a casual football fan, but to be football literate , you would need to be able to understand and read the playbook, have an understanding of the positions, define terms like “offsides” or “holding” as they relate to the sport, and interpret the hand signals used by the referees.

Educator and writer Shaelynn Faarnsworth describes and defines literacy as “social” and “constantly changing.” In this unit, we’ll explore literacy as a changing, dynamic process. By expanding our definition of literacy, we’ll come to a better understanding of our skills as readers and writers. We’ll use this discussion so that you, as writers, can better understand and write about “what skills [you] get and what [you] don’t, [and include your] interests, passions, and quite possibly YouTube.”

Checking In: Questions and Activities

- Consider our expanded definition of literacy. In what ways are you literate? What activities and/or hobbies do you value? How do they help give meaning to your world?

- When, where, and how do you read and write on a daily basis? These activities can occur in traditional formal contexts or in the most informal situations (like writing in group text message threads with your friends or posting on specific social media sites).

- Thinking of traditional literacy (reading and writing), what successes or challenges have you faced in school, at home, in the workplace, etc.?

Close Reading Strategies: Introducing the Conversation Model

Reading is a necessary step in the writing process. One helpful metaphor for the writing process is the conversation model. Imagine approaching a group of friends who are in the middle o

f an intense discussion. Instead of interrupting and blurting out the first thing you think of, you would listen. Then as you listen, you may need to ask questions to catch up and gain a better understanding of what has already been said. Finally, once you have this thorough understanding, you can feel prepared to add your ideas, challenge, and further the conversation.

Similarly, when writing, the first step is to read. Like listening, this helps you understand the topic better and approach the issues you’re discussing with more knowledge. With that understanding, you can start to ask more specific questions, look up definitions, and start to do more driven research. With all that information, then you can offer a new perspective on what others have already written. As you write, you may go through this process — listening, researching, and writing — several times!

This unit focuses first on the importance of reading. There are two important ways we’ll think about reading in this course. Close reading and critical reading are both important processes with difference focuses. Close reading is a process to understand what is being said. It’s often used in summaries, where the goal is to comprehend and report on what a text is communicating. Compared to critical reading, an analytical process focused on how and why an idea is presented, close reading forces us to slow down and identify the meaning of the information. This skill is especially important in summaries and accurately quoting and paraphrasing.

Close reading, essentially, is like listening to the conversation. Both focus on comprehension and being able to understand and report back on what is written or said. In this project,

- Within close reading, your processes could be further broken down into pre-reading, active reading, and post-reading strategies. What do you focus on before and after you read a text?

- There are many ways to read closely, and being an intentional reader will help ensure you process what you read and recall it later. However, there are many ways to actively read.

Consider assignments you’ve been given in the past:

- Have your instructors asked you to annotate a text?

- Do you find yourself copying down important lines, highlighting, or making notes as you read?

- What strategies do you rely on to actively and closely read?

- What are your least favorite strategies?

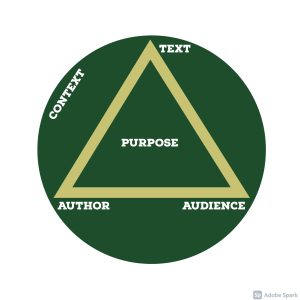

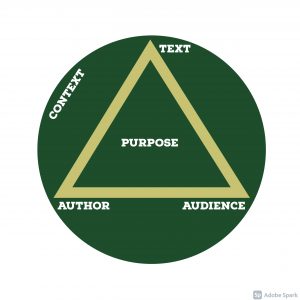

The Rhetorical Situation

You may have heard of “rhetorical questions” or gotten frustrated watching the news when a commentator dismisses another by saying “that’s just empty rhetoric” — but what does rhetoric mean? With definitions dating back to Aristotle and Plato, this is a complex concept with many historical and contemporary definitions. We define rhetoric as the ways language and other communication strategies are used to achieve a purpose with an audience. Below, we’ll explore the rhetorical situation, examining how many different factors contribute to how a writer can achieve their goals, and what may influence them to make different decisions.

The rhetorical situation is composed of many interactive pieces that each depend on the other. Let’s start by defining each component:

- Ask yourself: Who created this?

- Ask yourself: Who is likely to, or supposed to, see this?

- Ask yourself: What am I looking at?

- Ask yourself: Why was the text created?

- Ask yourself: When was this created? How did it get developed? Where was the text published? What shaped the creative process?

Each of these categories intersects and influences the other. When we think about a complete rhetorical situation, you’ll need to define all these different pieces to best understand the text. As we begin practicing close reading, drawing the rhetorical situation will be a helpful tool.

Let’s examine this project, the literacy narrative.

- Author : You! While you have a unique background, you’re a student in this course, and your individual writing experience will influence what you write about.

- Audience : Your classmates and instructor. This is a collaborative course, and your instructor will read what you produce.

- Text : Literacy Narrative. This type of text has different goals and requirements. We’ve examined literacy already, and we’ll review narratives soon. Together, these guidelines will help us construct this specific type of text (rather than a poem about reading or your personal memoir about how you became a writer!).

- Purpose : To reflect. To introduce yourself. To define your literacy. These are all goals of this assignment. Throughout your assignment, you’ll want to check in with yourself and ensure that you’re accomplishing these goals. If not, you won’t meet the demands of the assignment.

- Context : This assignment — the assignment sheet above has specific requirements that will influence what you create. Your writing background — no one else has the same life experience with reading and writing as you. The goals of the course — there are specific tasks to accomplish with this project that are specific to course outcome objectives. Each of these aspects will influence how you put the project together. Since you didn’t just wake up and decide to write about literacy, the context of this assignment will determine what you create.

- Which of the elements of the rhetorical triangle influence your writing decisions most? Why?

- Are there any elements you don’t consider? Why don’t they seem as important?

Section 2: Defining Narrative and Organization

Now that we’ve reviewed some basics, let’s take a look at the assignment more fully, begin drafting, and work more closely with feedback from others. A literacy narrative is a specific type of genre, so there are certain requirements for this text. Using examples from other students, we’ll begin to develop your first draft.

Introducing the Literacy Narrative

narrative : a method of story-telling

A literacy narrative is a common genre for writers who want to explore their own experiences with writing. Just Google “literacy narrative” and find endless examples! While this assignment will respond to specific prompts and follow a more specific structure than some of the examples you’ll find on Google, there is a common theme in each essay that revolves around your relationship with literacy. Section One defined literacy, but what about narrative? Narrative can be defined as a method of story-telling. In the simplest terms, your goal in this literacy narrative, in this assignment, is to tell the story of your personal experience with literacy, either from a past event, something you’re working with now, or looking to the future. Let’s review the three sets of prompts from the assignment sheet:

- Describe a situation when you were challenged in your reading by describing the source of that challenge (vocabulary, length, organization, something else). How did you overcome that challenge to understand what the text was saying? What strategies or steps do you plan to take in the future to make the process easier? This can range from reading a difficult novel to trying to play a particularly complicated song.

- Describe the type of texts you read (watch, listen to, etc.) most often. What makes them easy or challenging to read and interpret? What strategies do you use to ensure that you fully understand them or can apply them? Again, remember that these activities can occur in traditional formal contexts or in the most informal situations (like writing in group text message threads with your friends or posting on specific social media sites). Listening to music and watching true crime documentaries also count as listening to and watching texts.

- Describe what kind of texts you think you will have to read or interpret in the future and where you will encounter these texts (i.e. future classes, your career, etc.). How do you think they might challenge you? What strategies will you use to overcome these difficulties?

- What non-traditional topics could you write about for this project? What activities and/or hobbies do you value? How do they help give meaning to your world?

Each of these prompts gives you the chance to tell your story and examine your experience with a specific type of literacy. As you consider the prompts, think about how you could tell a story to answer these questions. With this frame of mind, review the questions and activities below.

- Which prompt from the assignment sheet will you address? Why does this prompt appeal to you?

- Consider the brainstorming you did about the ways that you are literate. Which prompt matches those skills best? Are these skills you struggled with at first, skills you currently practice, or a skill that you’re learning and will use in the future? Use these notes to decide which set of questions you’ll focus on in this project.

Organization: PIE Method

Each prompt includes three questions, which we’ll use as the starting point for three paragraphs. In each set of prompts, your first paragraph will describe the text; remember, when thinking about reading a text, we can interpret this broadly, like with music and sports. The second paragraph will explore the challenges or successes you’ve experienced. Then, the third paragraph will focus on strategies and techniques for improvement. This way, you can tell a more complete story of your experience, sharing the details and emotions along the way and making readers feel like they’re right there with you. But how do you capture all this detail in a way that helps you organize your thoughts and keep your reader interested in the story?

We’ll use a formula for the paragraph structure called PIE, which stands for Point, Information, and Explanation. This method will help you plan what you want to say, and then give examples so you can show why each step was so important to you. Let’s review each part of the paragraph, and then we’ll look at how this applies to your literacy narrative with a student sample.

- In the literacy narrative: Since each paragraph responds to a question from the prompt, the Point of each paragraph should tell readers which question you’re answering. By rephrasing the question in your Point, you can signal to your classmates and instructor so that they know which question you’re answering.

- In the literacy narrative: Most of your evidence, in a narrative, will be from your experience. Report what happened, what you read, or what you learned. Naming these details can help your readers see through your eyes when you give specific examples.

- In the literacy narrative: Help your readers get inside your head and feel like they’re with you. Keeping the Point in mind and showing how all these ideas relate will bring the paragraph together by developing each example clearly and offering a thoughtful response to each prompt. How did you feel about the examples from the Information? Why was it was so significant? Why should your readers care about this experience? Answering these questions will help show your readers what you experienced so they can understand the significance and connect with you.

Together, these pieces all come together to create a strong, developed paragraph that responds to the question from the prompt more fully.

- Below is a sample paragraph that follows the PIE structure. It is coded for the different parts of the paragraph above, with the Point in bold , the Information in italics , and the Explanation underlined . The second paragraph has been shortened and has not been coded. First, review the parts of the coded example. Pay particular attention to how these elements work in harmony to build the paragraph. Then, review and identify the PIE elements in the second paragraph.

Planning a Draft

Now that we’ve reviewed all the components and the foundation for this assignment, you’re ready to begin your draft! We’ll focus just on the first paragraph here, but you can use these steps for each paragraph to construct your draft.

Consider the first question from each prompt, copied below, to decide if you’ll focus on a past experience, the present, or the future:

- Describe a situation when you were challenged in your reading by describing the source of that challenge (vocabulary, length, organization, something else).

- Describe the type of texts you read (watch, listen to, etc.) most often.

- Describe what kind of texts you think you will have to read or interpret in the future and where you will encounter these texts (i.e. future classes, your career, etc.).

- Describe your preferred mode of expressing yourself and communicating with the world.

Literacy Narrative Rough Draft

Using your brainstorming from previous weeks, and using the student sample as a reference, begin drafting using the PIE structure, following these steps below to build the first paragraph of your draft. This is just a first draft, so let yourself write freely! This doesn’t need to be perfect or even good — instead, the goal is to put ideas on paper.

- In your Point, rephrase one of the questions above. You can borrow some of this same language to signal to your readers and show which question you’re answering. Remember, this only introduces the main idea — no details yet!

- Review your brainstorming. Did you name specific examples? Add these to your paragraph to develop the Information. Name at least two examples. Each example you give should connect to the Point, providing evidence from your experience.

- Review the examples and start to Explain. How did you feel about the examples from the Information? Why was it was so significant? Why should your readers care about this experience? Ask yourself these questions for each example you include.

- Depending on your drafting process, it might be easy to tackle all three paragraphs at once and get everything down, or you might prefer to write one paragraph at a time.

- Throughout the course, practice with drafting one paragraph per day, or setting a timer to see what you can write in a specific amount of time.

- Review what you’ve written, and see if there are more details to add. Remember, the goal is to get as much as you can out of your head. Revisions will take place next.

Section Three: Peer Review and Revision

Peer review.

Peer review is an important part of the drafting process. It helps us learn from our classmates and see our own work in a different way. Writing can be a lonely and isolating experience that makes the process frustrating and unsatisfying. Getting to share your work with others can break that uncomfortable pattern!

That said, you may be new to sharing your work or have different experiences with peer review. Good peer reviews can spark creativity, help build on good ideas, and revise the rougher ideas. But, sometimes peer review can be challenging if your peer is too critical or too complementary, or maybe you can’t read and understand what they wrote! The tips below will help reinforce best practices, as well as avoid some common mistakes with peer review.

When completing peer review, one important rule is to focus on the big picture and NOT to edit. Think about it like this: If you add a comma, then you’ve helped make one sentence of the paper better. In a paper that’s 1,000 words long, that’s not so helpful! Instead, consider the rhetorical triangle. If you can make observations and ask questions to help your classmate understand the audience or the genre better, then the entire paper is going to improve, because you focused on a higher order concept that affects not just one sentence, but the paragraph and the whole paper. Throughout these projects, we’ll practice several strategies for peer review so you can see several example methods and find what works best for you.

Peer workshop

When you sit down with your peer’s paper, we’ll practice a three-step process. This gives you a chance to explain exactly what you mean while offering specific advice for your peer. Review the steps below:

- Observe : Make a statement or summarize what you see. Identifying a pattern in your peer’s work or repeating what you think your peer is saying can help your peer know if they’re communicating clearly. Using the rhetorical triangle to support these observations could be a helpful strategy!

- Explain : Critique what you see, explaining if the writer has a strong idea or if it might need work. U sing adjectives to describe what’s going well or what’s not working is important so that you peer can learn more about your observation. Was this “clear” or “confusing”? Is the writer “engaging and interesting” or is the writing “plain and repetitive”?

- EXAMPLE: 1) You give a few examples for information, then a sentence of explanation. 2) It doesn’t look like this meets the word limits from the assignment sheet, and I’m not sure which part you’ll focus on as the main form of literacy. 3) Could you clarify this? More explanation about why these are important could help you meet the word limit, too!

All together, these comments will need to be a few sentences long. Since we’re NOT focused on grammar or editing, the changes that your peer can make will have a big effect on the final product. With these more developed comments, your goal is to make 1-2 comments per paragraph. Give your classmate something to consider, using our course vocabulary, to really help them improve. As you read and practice this method, it’s likely that you’ll get ideas for your own paper, which makes this process doubly helpful!

Assignment Rubric

- Will clearly and accurately define a specific type of literacy, explaining the connection and development of literacy. Will clearly establish the identity of the writer and the influence and importance of literacy.

- Will communicate significant experiences to an academic audience. Will give the reader something new to consider. Will interest the reader through storytelling.

- Will remain focused on literacy and the individual prompts. Will include specific details from a variety of experiences. Will engage readers with details and examples. Will explain the connections and development of growth through chosen examples.

- Will follow PIE structure closely.

- Will be clear and readable without distracting grammar, punctuation or spelling errors.

A “B” (good) summary (80% +):

- The concept of literacy may not be as clearly connected or central to the writer’s development.

- More attention could be paid to engage or interest the readers. May lack context to help the reader understand the writer’s experience.

- Focus may lack through discussing events outside of the prompts. May include few specific examples. May lack explanation to show connection between examples.

- PIE may not be followed in one paragraph. Either the point, information, or explanation could be further developed or clarified within a paragraph.

- The writer may need to work on communicating information more effectively. The narrative will be generally clear and readable but may need further editing for grammatical errors.

A “C” (satisfactory) summary (70% +):

- Literacy is not defined or explained clearly in connection to skill.

- Awareness of audience is lacking, making sections confusing for an unfamiliar reader.

- Prompts may not be clearly connected to the paragraphs. Examples are not included or are not clearly explained.

- PIE may be missing or underdeveloped in multiple paragraphs.

- “C” narratives may also need more editing for readability.

A “D” (poor) summary (60% +):

- Will show an attempt toward the assignment goals that has fallen short. May have several of the above problems.

An “F” (failing) summary:

- Ignores the assignment.

- Has been plagiarized.

- Review the same sample paragraph below from a previous student. Identify one strength and one area for improvement in the draft, following the 3-step method above. As you review, consider how to balance praise and criticism. Something is going well in your peer’s draft, and something can be improved!

Most of this week revolves around drafting activities. This week brings our first revisions and peer reviews, an important part of the writing process. With your peers, you’ll get to review what they’ve been working on while receiving feedback on your own work. Similar to the sample, it will be your responsibility to identify strengths and praise your peers’ writing, as well as identify areas for improvement and explain why this is an important revision they must make.

Applying Peer Review: Taking Suggestions and Revising

Once you’ve completed peer review, you’ll likely have lots of ideas — reviewing others’ work often ignites a creative spark for your own work! You should feel free to apply strategies from your peers and reexamine your work, but you want to focus on your peers’ suggestions for you. This way, you can see how your ideas and their commentary lines up. In our 3-step feedback process, the last step is to make a suggestion. While the notes from your peers should be valuable, it’s ultimately your draft and your decision about what feedback to include. As you read through the commentary, review the assignment sheet, and begin making changes to the draft. This is one of the most important steps in the writing process and what makes the difference between a rough first draft and a polished, complete draft.

Sources Used to Create This Chapter

- The majority of the content for this section has been adapted from OER Material from “Literacy Narrative,” in First-Year Composition by Leslie Davis and Kiley Miller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Media Resources

Any media resources not documented here were part of the original chapter from which this section has been adapted.

- “What is Your Story?” Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash

Works Referenced

Lunsford, Andrea. “Our Semi-literate Youth? Not So Fast.” Stanford University. Nov. 2010. https://swap.stanford.edu/was/20220129004722/https:/ssw.stanford.edu//sites/default/files/OPED_Our_semi-literate_Youth.pdf

Starting the Journey: An Intro to College Writing Copyright © by Leonard Owens III; Tim Bishop; and Scott Ortolano is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A Teacher's Guide to First-Year Writing

Baruch college first-year writing program, lisa blankenship: literacy narrative.

Introduction: This assignment asks students to tell a story about an experience they’ve had in which they felt they were stereotyped or misunderstood, using the concepts of literacy and discourse communities to focus particularly on the role of language. Students have just written a rhetorical analysis, and now they’re using concepts and interpretative lenses we discussed to analyze their own identity formation within a certain discourse community, paying particular attention to the role of stereotyping. See “Schedule” on our course blog for readings and daily activities.

Click here to view the syllabus associated with this assignment.

This assignment contains three parts: Assignment Sheet ( PDF ), Writer’s Letter Directions ( PDF ), and Peer Review Sheet ( PDF )

Assignment Sheet

ENG 2100: Writing 1

Identity, Rhetoric, and Propaganda in the “Fake News” Era [1]

Section JMWB • Fall 2018

Project 2 Assignment: Literacy Narrative

Your next major writing project (“Literacy Narrative”) will ask that you tell a story about the various ways you identify yourself in the world and how others see you (or how you think they see you).

Think of the various ways you would describe yourself to someone who doesn’t know you. Pay particular attention to the language you use. Why is this language significant? What discourse communities are you part of? How have those communities changed over time and why? What stereotypes do you think people may have about you and other people in a discourse community you’re in (those who are outside that group?)? What are some stories you could tell about how you’ve been misunderstood or just not fully known because people draw conclusions about people who are “like you.” How do language and literacy come into play in your story? Your story could be focused on language acquisition (traditional literacy narrative similar to the ones we’ll read in class), or it could focus on the literacy practices associated with a group you’re part of. (Remember that language can involve words or other symbols and literacy is how we “get by” or come to have power or cultural capital within certain communities or groups.) What words have been associated with people in your group(s)? Why is the particular language associated with your group(s) significant? What’s the history of that language or the words you consider important in your story and that have been used to describe you?

Stereotypes function as glosses or vague snapshots of people in a certain group rather than full pictures of an individual. What are examples of this principle in your life? How have you resisted stereotypes and tried to assert yourself as an individual? What positive function can group identity have? What are the negative functions? For your next assignment I’ll ask you to look at examples of stereotyping in culture: either in media, literature, pop culture, or politics. For now I want you to focus on yourself: tell a story and analyze your own story using some of the lenses we’ve explored so far this term. You’re doing a rhetorical analysis of your own story and experiences, in a sense.

Expectations

Narrative (30%)

Do you tell a compelling story with realistic dialogue, sensory description (show not tell), and details that make readers want to keep reading? While you may include reflective writing about the topic for the assignment, do you avoid clichés, generalizations, and vague reflections, and instead focus primarily on one particular moment or example that captures the point you’re trying to convey?

Thesis/Analysis (30%):

What is the thesis or the “so what?” of the piece? What insight does it offer? What argument does it make about the relationship between language and identity? Do you use concepts / key terms from the course text about language, discourse, discourse communities, and ideology to provide an analytical component to your piece?

Organization (20%):

Does the organization make sense and add to the meaning of the piece? Is it interesting and logical?

Style, Grammar, and Editing (15%):

Have you edited and proofread carefully so that no grammatical or spelling errors detract from the message and your credibility as a writer?

Process (5%):

You complete your first draft, you give feedback to your peer partner(s) on theirs, and you provide your readers (your peers and me) a writer’s letters on your first draft that includes the following: your reflections on your writing process so far (how much time you’ve spent on the invention and drafting process, how “finished” the draft is, and what you still need to work on and what you’re happy with). In other words, knowing your paper will be graded using the above criteria, how well have you addressed each one of them? You also include specific questions you have for your reviewers. For your final writer’s letter, you revisit these questions and add a detailed explanation of what you changed after getting feedback (what you revised) and what you gained from this assignment.

- ~1,500 words / 2.5 single-spaced pages

- 20% of course grade

- Draft 1 with writer’s letter (peer review): Wed, Oct 31

- Revised draft with writer’s letter: Wed, Nov 7

[1] Image credit: “Keep Your Head Up” by Joeri Mages . Used by permission through Creative Commons licensing .

Writer’s Letter

REVISED Writer’s Letter Assignment: Literacy Narrative

For the revised, final draft of your Writer’s Letter, please respond to the following and save it as page 1 of your draft. Please use paragraph form as with a cover letter; don’t respond to these questions in bullet format.

Describe what your topic is and why you chose it.

How has this project changed how you view your own literacy story and history as part of a discourse community or communities?

Describe your main point/insight/thesis.

Describe how you support that thesis in your paper (be specific: in the first section I do <x>; in the second I do <x> etc.

Write about your revision and final drafting process. What did you revise based on feedback for this final draft? Be specific; use terminology and concepts from the rubric below that I’ll use to give you feedback and determine your grade.

What was the peer review like for you? What did you find useful? Not so useful? What would you like to do differently or wish would be done differently next time? Was it more helpful this time than last?

What’s the purpose of writing this paper? Why do you think I chose this assignment? What do you think could be improved if I use this assignment again?

Were the readings on literacy and language from Join the Conversation helpful for this paper (especially the Introduction to “(re)Making Language,” “Language, Discourse, and Literacy,” “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” The Meanings of a Word,” and “Mother Tongue”? Any feedback you have would be helpful as we revise this text for larger rollout for ENG 2100 classes next fall.

What grade do you think this paper warrants, using the rubric below? Be specific: use the rubric to determine how well you think you did and support your grade with examples from your writing itself.

Title the file: “LastnameFirstname_LiteracyNarrative_final.docx” (no need to convert to a Google Doc this time).

GRADING CRITERIA

For this paper I’ll be looking for the following. (Each category is worth a certain percentage of the overall paper grade as indicated below, based on 100% total.)

Peer Review Directions

Peer Review Directions: Literacy Narrative

Writer’s Name:

- Read over the writer’s letter and the paper in their entirety first, making note of the questions the writer asks of you as a reader. If you notice anything that trips you up or that you have questions about, make a note about it in the margin of the paper using the “Comment” feature. (Put your cursor where you want to insert the comment, go to “Insert” at the top menu bar, then choose “Comment” and type your comment in the margin. This allow you to comment without changing the writer’s words.)

- Write the title of the piece below. Is it creative? Does it make you want to keep reading? Does the title point to the thesis or insight of the paper?

- What kind of story is the writer telling? What is this piece about?

- How well does the writer hook you in as a reader? (e.g. are there descriptive details that help you imagine the story better and make you feel a bit of what they went through?) Where could the narrative itself be stronger?

- Write what you believe is the writer’s thesis/insight below. Also, make a comment in the paper where you believe the thesis is insert a comment there simply reading “Thesis.” (This will help you discern how well the writer has completed one of the main goals for this assignment, #2 on the grading rubric, next page).

- Is this thesis focused enough at this point? Could it be clearer? Is it interesting to you? Does it give you an insight that you may not have thought about otherwise? If no to any of these, what advice could you give as a reader about how to make the thesis stronger and more compelling?

- Do they include any concepts / key terms / critical lenses we’ve discussed in class?

- In terms of organization (#3 on the rubric), do you see any paragraphs that seem out of place / could be deleted / further developed? Describe them here.

- Did you feel “tripped up” or lost at any point reading this?

- What did the writer do really well in your view? What’s the strongest part of this piece of this piece of writing?

- What area do you think the writer most needs to work on to make the piece stronger? (Again, pay close attention to the writer’s own questions and self-critique here as well.)

- Finally, make sure you’ve responded to any questions the writer asked in the cover letter.

When you finish, save this document and post it to your group’s folder, using the writer’s name in the title to avoid confusion. For example: Mike’sReview.docx (and your name will appear as the person posting). Prof. Blankenship will post feedback for you on your draft in the same folder (within your Google Doc saved in your group’s file) by end of day Friday.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

![literacy narrative peer review sheet SASC - Student Academic Success Center - UNE [logo]](https://files.uneportfolio.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2022/02/SASCLogoSquare_Smaller-3-e1644936452801.jpeg)

Dr. Eric Drown

Reading and Writing are Superpowers*

Peer Review for Literacy Narrative

Remember, a story is shaped by characters experiencing conflict or tension, who take a series of actions in scenes (often with dialogue ), working towards a climax in which they experience a moment of insight or revelation .

As you read your peer’s literacy narrative drafts, write comments to help the writer improve these global dimensions of their writing:

- How well does the opening work to introduce a main character experiencing conflict and to initiate a series of actions?

- What is the main conflict or tension in the narrative? Do all the scenes in the story contribute to developing or resolving that conflict or tension?

- What moment of insight or revelation does the character have in this story? Do the scenes that precede it prepare readers to understand that moment of insight?

- What parts of the story could use more detail or development?

- How well does the ending work to connect the story to the writer’s present self?

- If the writer has included a text-to-self connection to Sherman Alexei or Mike Rose, is the connection well-integrated into the story the writer is telling about his or her own literacy experiences?

A good comment will:

- Be generous and considerate in tone;

- Describe what you see or think as a reader, leading to a diagnosis of a problem or description of an improvement to be made;

- Suggest a specific strategy for improvement;

- Provide additional insight by: asking leading questions, providing further detail, suggesting specific materials for inclusion, or engaging in dialogue with the writer.

- Indicate whether this is a high-, medium-, or low-priority issue.

Aim for no more than two comments per page.

In an end comment, write some sentences that give the writer an idea of your overall impression or general effect of the paper. If you can, explain the central insight you have gotten from the paper as a careful reader. Consider making a text-to-self connection here as well.

Exploring and Sharing Family Stories

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

In this lesson, students are encouraged to explore the idea of memory in both large- and small-group settings. Students access their own life experiences and then discuss family stories they have heard. After choosing a family member to interview, students create questions, interview their relative, and write a personal narrative that describes not only the answers to their questions but their own reactions to these responses. These narratives are peer reviewed and can be published as a class magazine or a website.

From Theory to Practice

- The topic of memory can engage students in both reading and writing, especially if those activities act as a bridge between school and family.

- Students can be encouraged to view their own life history and that of other family members as a composition that is created through memory and that is therefore subject to constant revision and documentation.

- Requiring students to pay attention to and craft both their own memories and those of other people can help them become more thoughtful readers and writers in other contexts.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

- Video or tape recorders (optional)

- Chart paper

- Note to Families

- Personal Narrative Assignment Sheet

- Oral History Questions worksheet

- How to Interview a Relative worksheet

- Peer Review Worksheet

- "Mixing Memory and Desire: A Family Literacy Event" by Mark Faust

- Family Memories Narrative Rubric

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Access personal and family memories by discussing them in large- and small-group settings

- Demonstrate comprehension by reviewing other personal narratives and discussing how they might apply some of the same techniques to their own work

- Apply critical-thinking skills by translating what they see in these narratives into potential interview questions

- Practice knowledge acquisition by learning how to best conduct an interview and taking notes during their interview to use for their future personal narrative.

- Work collaboratively by peer reviewing each other's work

- Practice synthesizing information and writing by assembling their notes into a personal narrative

Homework (due by Session 3): Students should bring home the Note to Families and talk about interviewing an older relative. With help, they should determine whom they are going to talk to for this assignment and how the interview will be conducted (for example, over the phone or email or by visiting the relative). Students should contact the relative and should come to Session 3 with a name and the format their interview will take.

Homework (due before Session 4): Write at least five interview questions.

Note: Students need to have finalized their interview questions by this session. You may need to leave time for them to turn in several drafts.

Homework: Students should complete their interviews and write drafts of their personal narratives by Session 5. The amount of time you give students to complete this work is up to you, but it should be a minimum of a week.

Sessions 5 and 6

Homework: Students should revise their personal narratives using the feedback from the peer review sheets. They should turn in these sheets along with their interview questions and notes when they hand in their final personal narrative. You may want to give them time (and encourage them) to contact their relatives for further questioning or clarification after the peer review sessions.

Bring the class back together for a final discussion about memory and what they learned by interviewing their relative and writing the personal narrative. Questions for discussion include:

- When reading other people's narratives, did you see any similarities with your own narrative? What were they?

- What was unique to your own narrative?

- Did you see any differences in experiences based on where people lived?

- Why do you think it is important for people to share their life stories?

- If you were writing your own life story, what are some things you would include?

- Publish the student narratives as a magazine or website. If you do this, you might collect family photos from each student. Allow students time in class to review the publication.

- Have students share their stories with younger classes. A class "author's night" could also be arranged to share stories with family members (including interview subjects).

- Have students read the novel The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman by Ernest Gaines (Bantam, 1982). Have students compare this fictional personal narrative with the ones they wrote.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- Assess student participation during both whole-class discussions and small-group work using your observations and anecdotal notes.

- Evaluate the interview questions and the notes from the actual interview. How well were students able to use the materials you provided (the Oral History Questions worksheet and the How to Interview a Relative worksheet) to develop their interview questions and conduct their interviews? Did students choose thoughtful and appropriate questions? Did they use these questions during the interview? Did they take opportunities to ask related questions while interviewing their relative?

- Use the Family Memories Narrative Rubric to evaluate the completed personal narratives and peer review forms.

Students imagine they have been asked to participate in a museum exhibit, take photos/videos of a significant location, and write or record reflections. Students can also create an exhibit from something they have read.

Students interview a parent or another adult about the Challenger and hypothesize about differences. Students can also write about the Columbia disaster in 2003.

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

3.5 Writing Process: Tracing the Beginnings of Literacy

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a writing project through multiple drafts.

- Use composing for inquiry, learning, critical thinking, and communicating in various rhetorical, cultural, and language situations.

- Give and act on productive feedback to works in progress.

- Benefit from the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes.

- Use language structures, including multilingual structures, grammar, punctuation, and spelling, during the processes of composing and revising.

Many inexperienced writers imagine that “good” writers compose their texts all at once, from beginning to end, and need only a small amount of attention to polish the grammar and punctuation before arriving at a final draft. In reality, however, the writing process (steps for creating a finished composition) is typically recursive . That is, it repeats steps multiple times, not necessarily in the same order, and the process is more messy than linear or systematic. You can think of the writing process in terms of these broad categories:

- Prewriting. You will end up with a stronger composition if you do some work before you begin writing. Before putting complete sentences on a page, take some time to think about the rhetorical situation for your writing, gather your thoughts, and consider how you might arrange your ideas.

- Drafting. In the past, you may have dedicated most of your writing time to drafting, or putting words into a document. When you have strong prewriting and revision habits, however, drafting is often a smaller portion of the writing process.

- Peer Review. Almost all strong writers rely on feedback from others, whether peers, instructors, or editors. Your instructor may guide you in some peer review exercises to complete with your classmates, or you might choose to consult with your university’s writing center. When others give you clear, honest feedback on your draft, you can use that information to strengthen your piece.

- Revision. After you have a draft, carefully consider how to make it more effective in reaching the audience and fulfilling its purpose. You can make changes that affect the piece as a whole; such changes are often called global revisions. You can also make changes that affect only the meaning of a sentence or a word; these changes can be called local revisions.

Summary of Assignment: Independent Literacy Narrative

In this assignment, you will write an essay in which you offer a developed narrative about an aspect of your literacy practice or experience. Consider some of these questions to generate ideas for writing: What literacies and learning experiences have had profound effects on your life? When did this engagement occur? Where were you? Were there other participants? Have you told this story before? If so, how often, and why do you think you return to it? Has this engagement shaped your current literacy practices? Will it shape your practices going forward?

The development of your literacy experiences can take multiple paths. If you use the tools provided in this section, you will be able to effectively compose a unique literacy narrative that reflects your identities and experiences. The questions prompting your writing in this section can help you begin to develop an independent literacy narrative. The next section, on community literacy narratives, helps you consider your composition course community and ways to think about your shared experiences around literacy. The following section, on literacy narrative research, guides you to a database of literacy narratives that offer an opportunity to analyze the ways in which others in the academic community have reflected on their literacy experiences. Further sections will guide you through the development and organization of your work as you navigate this genre.

Another Lens 1. As an alternative to an individual literacy narrative, members of your composition course community can develop a set of interview questions that will allow you to learn more about each other’s past and present experiences with literacy. After the community has determined what the interview questions will be, choose a partner from the composition community to work with on this assignment; alternatively, your instructor may assign partners for the class. Using the interview questions you have discussed and developed, you will conduct an interview with your partner, and they with you. Your instructor will allow you and your peers to record and transcribe one another’s responses and post them where all students in the community have access. After you have completed, transcribed, and posted your interviews, everyone will closely examine each of their peers’ interviews and look for recurring themes as well as unique aspects of the narratives shared. This assignment will inevitably illuminate both the communal nature and the unique, independent experiences of literacy engagement.

Another Lens 2. Using DALN , perform a keyword search for literacy narratives on one aspect or area of concentration that interests you, such as music, dance, or poetry. Select two or more narratives from the archive to read and analyze. Read and annotate each narrative, and then think about a unique position you can take when discussing these stories. Use these questions to guide the development of your stance: Do you have experiences in this concentrated area of literacy? If so, how do your experiences intersect with or depart from the ones you are reading? What common themes, if any, do these narratives share? What do these narratives reveal about literacy practices in general and about this area of concentration in particular?

Quick Launch: Defining Your Rhetorical Situation, Generating Ideas, and Organizing

When you are writing a literacy narrative, think about

- your audience and purpose for writing;

- the ideas and experiences that best reflect your encounters with various literacies; and

- the order in which you would like to present your information.

The Rhetorical Situation

A rhetorical situation occurs every time anyone communicates with anyone else. To prepare to write your literacy narrative, use a graphic organizer like Table 3.1 to outline the rhetorical situation by addressing the following aspects:

Generating Ideas

In addition to these notes, write a few ideas relating to your literacy experiences. Feel free to use bullet points or incomplete sentences.

- What instructors, formal or informal, helped or hindered you in learning literacies?

- Which of your literacies feel(s) most comfortable?

- Which literacy experiences have transformed you?

- Do you use specialized language to signal your identity as part of a community or cultural group?

- After you look back over your notes, what is the most compelling story about a literacy or literacy experience that you can share, and what is the significance of that story?

In one last step before beginning to draft your literacy narrative, think visually about how you will put the pieces together.

- Where will you begin and end your literacy narrative, and what is your story arc? Will you jump right into some richly described action, or will you set the scene for the reader by describing an important story locale first?

- What tension will the story resolve?

- What specific sensory details, dialogue, and action will you include?

- What vignettes, or small scenes, will you include, and in what order should the audience encounter them?

- Some of your paragraphs will “show” scenes to your readers, and some of your paragraphs will “tell” your readers explanatory information. After you decide what elements to show to your readers through vivid descriptions and what elements you will inform your readers about, decide how to order those elements within your draft.

- Review the specific writing prompt given in the summary of the assignment, and make any additional notes needed in response to that material. Use visual organizers in such as those presented in Figure 3.10 through Figure 3.13 to develop the plan for your draft:

Use the graphic organizer structure above that best helps you establish the narrative arc for your literacy story, including the following elements:

- Beginning. Set the scene by providing information about the characters, setting (where and when the narrative takes place), culture, background, and situation.

- Rising Action. In each successive section, whether it is a paragraph or more, add dialogue and other details to make your story vivid and engaging for readers so that they will want to continue reading. Tell your story in an order that makes sense and is clear to readers.

- Climax. At this point, show what finally happened to clinch the experience. How did the literacy experience finally take hold? Or why didn’t it? What happened at this “climactic” moment?

- Falling Action. This is the part where the tension is released and you have achieved—or not—what you set out to do. This section may be quite short, as it may simply describe a new feeling or reaction. It leads directly to the next section, which may be more reflective.

- Resolution. This is a reflective portion. How has this new literacy affected you? How do you view things differently? How do you think it affected the person who taught you or others with whom you are close?

Drafting: Writing from Personal Experience and Observation

Now that you have planned your literacy narrative, you are ready to begin drafting. If you have been thoughtful in preparing to write, drafting usually proceeds quickly and smoothly. Use your notes to guide you in composing the first draft. As you write about specific events and scenes, create a rich picture for your reader by using concrete, sensory details and specific rather than general nouns as shown in Table 3.2 .

Using Frederick Douglass’s Text as a Drafting Model

As Douglass does, create your literacy narrative from your recollections of people, places, things, and events. Reread the following passage.

public domain text The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent of errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge. I am strongly tempted to give the names of two or three of those little boys, as a testimonial of the gratitude and affection I bear them; but prudence forbids;—not that it would injure me, but it might embarrass them; for it is almost an unpardonable offence to teach slaves to read in this Christian country. It is enough to say of the dear little fellows, that they lived on Philpot Street, very near Durgin and Bailey’s ship-yard. I used to talk this matter of slavery over with them. I would sometimes say to them, I wished I could be as free as they would be when they got to be men. “You will be free as soon as you are twenty-one, but I am a slave for life ! Have not I as good a right to be free as you have?” These words used to trouble them; they would express for me the liveliest sympathy, and console me with the hope that something would occur by which I might be free. end public domain text

In this selection from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , elements of the literacy narrative genre as explained in Glance at Genre: The Literacy Narrative are evident. First, Douglass introduces additional characters who help him resolve his earlier complication of being prevented from learning to read by the Aulds. The interaction he records here reiterates the larger conflict of the narrative: Douglass’s continuing enslavement. Although he does not give many scenic details, few more would be needed, for he places the action on the street near a shipyard, thereby giving an indication of the surroundings. Douglass presents his own words in dialogue to reinforce for readers that he knows how to speak and write in the ways that white people with means were taught at the time. In this piece, set against the backdrop of a culture that insisted on viewing enslaved people as “brutes,” Douglass demonstrates his dignity by displaying his facility with language and his humanity by offering bread to hungry children who have more freedom and opportunity, but less food, than he does.

To create a draft that draws on multiple elements of storytelling, as this selection from Douglass does, you may need to generate ideas for additional scenes, or you may need to revisit a particular place so that you can provide concrete and sensory details for your readers. Refer to the storyboarding, web diagram, and plot flow charts in the “Organizing” section above to further develop your draft.

Another Way to Draft the Literacy Narrative

Read the literacy narrative by American author and educator Helen Keller (1880–1968). An Alabama native, Keller lost both sight and hearing after a serious illness as a young child. The selection relates a transformational literacy moment in her life, when Anne Sullivan (1866–1936), Keller’s teacher, helps her understand the connection between hand-spelled words and physical items. Keller’s literacies, along with heroic support from her teacher, later enabled her to complete college and tour as an activist and lecturer.

public domain text The most important day I remember in all my life is the one on which my teacher, Anne Mansfield Sullivan, came to me. I am filled with wonder when I consider the immeasurable contrasts between the two lives which it connects. It was the third of March, 1887, three months before I was seven years old. end public domain text

annotated text The introduction sketches the boundaries of this literacy narrative by noting that the arrival of a teacher separated Keller’s life into two distinct parts. end annotated text

public domain text On the afternoon of that eventful day, I stood on the porch, dumb, expectant. I guessed vaguely from my mother’s signs and from the hurrying to and fro in the house that something unusual was about to happen, so I went to the door and waited on the steps. The afternoon sun penetrated the mass of honeysuckle that covered the porch, and fell on my upturned face. My fingers lingered almost unconsciously on the familiar leaves and blossoms which had just come forth to greet the sweet southern spring. I did not know what the future held of marvel or surprise for me. Anger and bitterness had preyed upon me continually for weeks and a deep languor had succeeded this passionate struggle. end public domain text

annotated text This paragraph helps establish the problem to be resolved in this short narrative: Keller is “dumb” but “expectant.” Additionally, the three characters in this section have been introduced—mother, teacher, and Keller herself—though the audience has few details yet about any of them. The author provides some sensory details in this paragraph, however, including her mother’s movements, the afternoon sun, and the tactile feeling of the honeysuckle. end annotated text

public domain text Have you ever been at sea in a dense fog, when it seemed as if a tangible white darkness shut you in, and the great ship, tense and anxious, groped her way toward the shore with plummet and sounding-line, and you waited with beating heart for something to happen? I was like that ship before my education began, only I was without compass or sounding-line, and had no way of knowing how near the harbour was. “Light! give me light!” was the wordless cry of my soul, and the light of love shone on me in that very hour. end public domain text

annotated text When Keller’s autobiography was originally written, the audience was readers of the Ladies’ Home Journal , a monthly magazine popular with homemakers; Keller’s autobiography was published in monthly installments. Keller appeals to this audience with her allusions to Judeo-Christian imagery and an evocative writing style. While her wording may seem a bit overdone today, such phrasing would have been familiar to her contemporary readers. A year later, in 1903, Keller’s story was published as a book and expanded to a much wider audience. end annotated text

public domain text I felt approaching footsteps, I stretched out my hand as I supposed to my mother. Some one took it, and I was caught up and held close in the arms of her who had come to reveal all things to me, and, more than all things else, to love me. end public domain text

annotated text The subject of love often appears in the literacy narrative genre, whether love of a certain skill or pastime or love for a relative or teacher who taught a certain literacy. end annotated text

public domain text The morning after my teacher came she led me into her room and gave me a doll. The little blind children at the Perkins Institution had sent it and Laura Bridgman had dressed it; but I did not know this until afterward. When I had played with it a little while, Miss Sullivan slowly spelled into my hand the word “d-o-l-l.” I was at once interested in this finger play and tried to imitate it. When I finally succeeded in making the letters correctly I was flushed with childish pleasure and pride. Running downstairs to my mother I held up my hand and made the letters for doll. I did not know that I was spelling a word or even that words existed; I was simply making my fingers go in monkey-like imitation. In the days that followed I learned to spell in this uncomprehending way a great many words, among them pin, hat, cup and a few verbs like sit, stand and walk. But my teacher had been with me several weeks before I understood that everything has a name. end public domain text

annotated text With the introduction of finger spelling, this paragraph and the next present the rising action building toward the climax of this story. end annotated text

public domain text One day, while I was playing with my new doll, Miss Sullivan put my big rag doll into my lap also, spelled “d-o-l-l” and tried to make me understand that “d-o-l-l” applied to both. Earlier in the day we had had a tussle over the words “m-u-g” and “w-a-t-e-r.” Miss Sullivan had tried to impress it upon me that “m-u-g” is mug and that “w-a-t-e-r” is water, but I persisted in confounding the two. In despair she had dropped the subject for the time, only to renew it at the first opportunity. I became impatient at her repeated attempts and, seizing the new doll, I dashed it upon the floor. I was keenly delighted when I felt the fragments of the broken doll at my feet. Neither sorrow nor regret followed my passionate outburst. I had not loved the doll. In the still, dark world in which I lived there was no strong sentiment or tenderness. I felt my teacher sweep the fragments to one side of the hearth, and I had a sense of satisfaction that the cause of my discomfort was removed. She brought me my hat, and I knew I was going out into the warm sunshine. This thought, if a wordless sensation may be called a thought, made me hop and skip with pleasure. end public domain text

annotated text In Keller’s “still, dark world,” she offers little indication of setting, giving the audience only glimpses of her surroundings: honeysuckle, a house with interior stairs, and a hearth in her teacher’s room. Because she could not converse at the time, the only dialogue in this story appears in the form of the finger-spelled words. Plot tensions rise with Keller’s action of breaking the doll. end annotated text

public domain text We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water , first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that “w-a-t-e-r” meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away. end public domain text

annotated text Keller’s literacy in finger spelling not only laid the foundation for her future literacies in reading, writing, and speaking but also provided her foundational access to language itself. This paragraph provides the climax of this story as well as the resolution for the problem introduced earlier; having been introduced to language, Keller is no longer “dumb” (though she cannot yet speak). end annotated text

public domain text I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought. As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life. That was because I saw everything with the strange, new sight that had come to me. On entering the door I remembered the doll I had broken. I felt my way to the hearth and picked up the pieces. I tried vainly to put them together. Then my eyes filled with tears; for I realized what I had done, and for the first time I felt repentance and sorrow. end public domain text

public domain text I learned a great many new words that day. I do not remember what they all were; but I do know that mother, father, sister, teacher were among them—words that were to make the world blossom for me, “like Aaron’s rod, with flowers.” It would have been difficult to find a happier child than I was as I lay in my crib at the close of that eventful day and lived over the joys it had brought me, and for the first time longed for a new day to come. end public domain text

annotated text The final two paragraphs offer falling action following the dramatic climax. end annotated text

Consider the ways in which Douglass’s account and Keller’s account are stylistically similar and different. Both use figurative language—“bread of knowledge”—and make allusions to the Christian tradition. However, Douglass uses dialogue to illustrate a social disparity, whereas Keller’s transformation and her language are largely internal. You should make use of the strategies that best fit your own literacy narrative as shown in Table 3.3 .

Peer Review: Giving Specific Praise and Constructive Feedback

Although the writing process does not always occur in a prescribed sequence (you can move among steps of the process in a variety of ways), participating in peer review is a necessary part of the writing process. Having the response and feedback of an outside reader can help you shape your writing into work that makes you proud. A peer review occurs when someone at your level (a peer) offers an evaluation of your writing. Instructors aid in this process by giving you and your peers judgment criteria and guidelines to follow, and the feedback of the reader should help you revise your writing before your instructor evaluates it and offers a grade.

When given the opportunity to engage in a peer review activity, use the following steps to provide your peers with effective, evidence-based feedback for their writing.

- Review all the criteria and guidelines for the assignment.

- Read the writing all the way through carefully before offering any feedback.

- Read the peer review exercise, tool, or instrument provided by the instructor.

- Apply and complete the peer review exercise while rereading the work.

- In what ways are the organization and coherence of the narrative logical and clear so that you can follow events?

- What, if anything, do you not understand or need further explanation about?

- What do you want to know more about?