How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

The FOCUS Model

A simple, efficient problem-solving approach.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Are your business processes perfect, or could you improve them?

In an ever-changing world, nothing stays perfect for long. To stay ahead of your competitors, you need to be able to refine your processes on an ongoing basis, so that your services remain efficient and your customers stay happy.

This article looks the FOCUS Model – a simple quality-improvement tool that helps you do this.

About the Model

The FOCUS Model, which was created by the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), is a structured approach to Total Quality Management (TQM) , and it is widely used in the health care industry.

The model is helpful because it uses a team-based approach to problem solving and to business-process improvement, and this makes it particularly useful for solving cross-departmental process issues. Also, it encourages people to rely on objective data rather than on personal opinions, and this improves the quality of the outcome.

It has five steps:

- F ind the problem.

- O rganize a team.

- C larify the problem.

- U nderstand the problem.

- S elect a solution.

Applying the FOCUS Model

Follow the steps below to apply the FOCUS Model in your organization.

Step 1: Find the Problem

The first step is to identify a process that needs to be improved. Process improvements often follow the Pareto Principle , where 80 percent of issues come from 20 percent of problems. This is why identifying and solving one real problem can significantly improve your business, if you find the right problem to solve.

According to a popular analogy, identifying problems is like harvesting apples. At first, this is easy – you can pick apples up from the ground and from the lower branches of the tree. But the more fruit you collect, the harder it becomes. Eventually, the remaining fruit is all out of reach, and you need to use a ladder to reach the topmost branches.

Start with a simple problem to get the team up to speed with the FOCUS method. Then, when confidence is high, turn your attention to more complex processes.

If the problem isn't obvious, use these questions to identify possible issues:

- What would our customers want us to improve?

- How can we improve quality ?

- What processes don't work as efficiently as they could?

- Where do we experience bottlenecks in our processes?

- What do our competitors or comparators do that we could do?

- What frustrates and irritates our team?

- What might happen in the future that could become a problem for us?

If you have several problems that need attention, list them all and use Pareto Analysis , Decision Matrix Analysis , or Paired Comparison Analysis to decide which problem to address first. (If you try to address too much in one go, you'll overload team members and cause unnecessary stress.)

Step 2: Organize a Team

Your next step is to assemble a team to address the problem.

Where possible, bring together team members from a range of disciplines – this will give you a broad range of skills, perspectives, and experience to draw on.

Select team members who are familiar with the issue or process in hand, and who have a stake in its resolution. Enthusiasm for the project will be greatest if people volunteer for it, so emphasize how individuals will benefit from being involved.

If your first choice of team member isn't available, try to appoint someone close to them, or have another team member use tools like Perceptual Positioning and Rolestorming to see the issue from their point of view.

Keep in mind that a diverse team is more likely to find a creative solution than a group of people with the same outlook.

Step 3: Clarify the Problem

Before the team can begin to solve the problem, you need to define it clearly and concisely.

According to " Total Quality Management for Hospital Nutrition Services ," a key text on the FOCUS Model, an enthusiastic team may be keen to attack an "elephant-sized" problem, but the key to success is to break it down into "sushi-sized" pieces that can be analyzed and solved more easily.

Use the Drill Down technique to break big problems down into their component parts. You can also use the 5 Whys Technique , Cause and Effect Analysis , and Root Cause Analysis to get to the bottom of a problem.

Record the details in a problem statement, which will then serve as the focal point for the rest of the exercise ( CATWOE can help you do this effectively.) Focus on factual events and measurable conditions such as:

- Who does the problem affect?

- What has happened?

- Where is it occurring?

- When does it happen?

The problem statement must be objective, so avoid relying on personal opinions, gut feelings, and emotions. Also, be on guard against "factoids" – statements that appear to be facts, but that are really opinions that have come to be accepted as fact.

Step 4: Understand the Problem

Once the problem statement has been completed, members of the team gather data about the problem to understand it more fully.

Dedicate plenty of time to this stage, as this is where you will identify the fundamental steps in the process that, when changed, will bring about the biggest improvement.

Consider what you know about the problem. Has anyone else tried to fix a similar problem before? If so, what happened, and what can you learn from this?

Use a Flow Chart or Swim Lane Diagram to organize and visualize each step; this can help you discover the stage at which the problem is happening. And try to identify any bottlenecks or failures in the process that could be causing problems.

As you develop your understanding, potential solutions to the problem may become apparent. Beware of jumping to "obvious" conclusions – these could overlook important parts of the problem, and could create a whole new process that fails to solve the problem.

Generate as many possible solutions as you can through normal structured thinking, brainstorming , reverse brainstorming , and Provocation . Don't criticize ideas initially – just come up with lots of possible ideas to explore.

Step 5: Select a Solution

The final stage in the process is to select a solution.

Use appropriate decision-making techniques to select the most viable option. Decision Trees , Paired Comparison Analysis , and Decision Matrix Analysis are all useful tools for evaluating your options.

Once you've selected an idea, use tools such as Risk Analysis , "What If" Analysis , and the Futures Wheel to think about the possible consequences of moving ahead, and make a well-considered go/no-go decision to decide whether or not you should run the project.

People commonly use the FOCUS Model in conjunction with the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. Use this approach to implement your solutions in a controlled way.

The FOCUS Model is a simple quality-improvement tool commonly used in the health care industry. You can use it to improve any process, but it is particularly useful for processes that span different departments.

The five steps in FOCUS are as follows:

People often use the FOCUS Model in conjunction with the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, which allows teams to implement their solution in a controlled way.

Bataldan, P. (1992). 'Building Knowledge for Improvement: an Introductory Guide to the Use of FOCUS-PDCA,' Nashville: TN Quality Resource Group, Hospital Corporation of America.

Schiller, M., Miller-Kovach, M., and Miller-Kovach, K. (1994). 'Total Quality Management for Hospital Nutrition Services,' Aspen Publishers Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Top tips for successful networking.

These Suggestions Will Help You Get Your Approach to Networking Off to a Great Start

Expert Interviews

Great at Work

Morten Hansen

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Team Management

Learn the key aspects of managing a team, from building and developing your team, to working with different types of teams, and troubleshooting common problems.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

SWOT Analysis

SMART Goals

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to stop procrastinating.

Overcoming the Habit of Delaying Important Tasks

What Is Time Management?

Working Smarter to Enhance Productivity

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Creating the conditions for high performance.

Building a high-performing team

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

35 problem-solving techniques and methods for solving complex problems

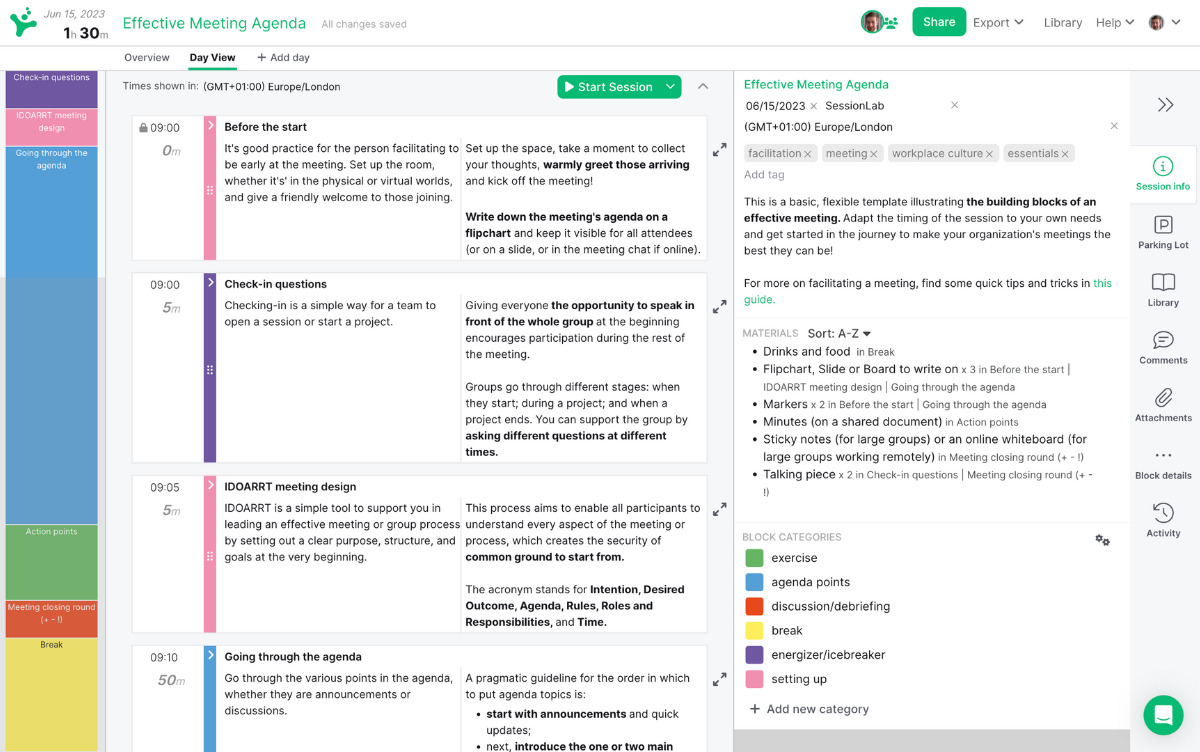

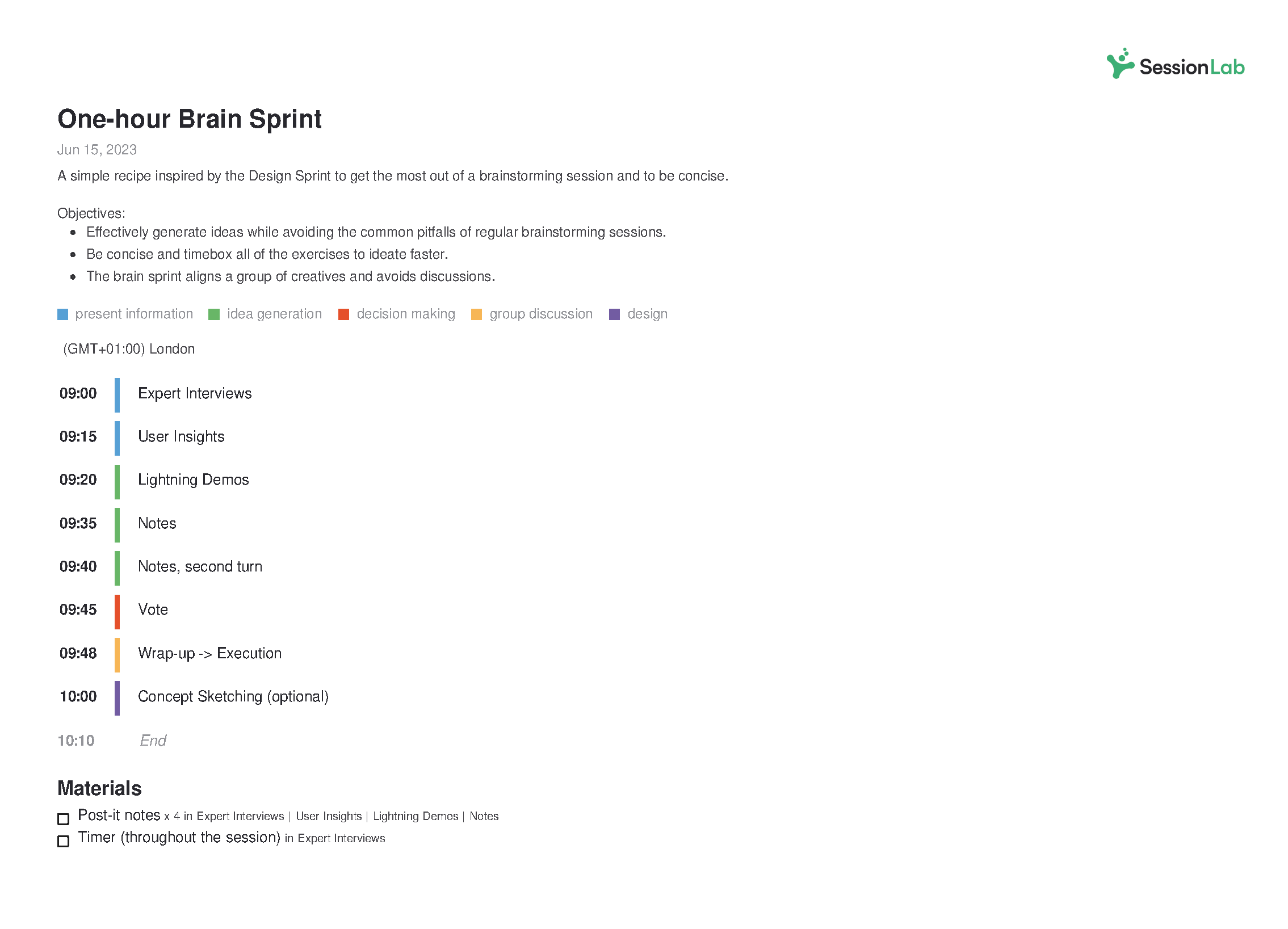

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

All teams and organizations encounter challenges as they grow. There are problems that might occur for teams when it comes to miscommunication or resolving business-critical issues . You may face challenges around growth , design , user engagement, and even team culture and happiness. In short, problem-solving techniques should be part of every team’s skillset.

Problem-solving methods are primarily designed to help a group or team through a process of first identifying problems and challenges , ideating possible solutions , and then evaluating the most suitable .

Finding effective solutions to complex problems isn’t easy, but by using the right process and techniques, you can help your team be more efficient in the process.

So how do you develop strategies that are engaging, and empower your team to solve problems effectively?

In this blog post, we share a series of problem-solving tools you can use in your next workshop or team meeting. You’ll also find some tips for facilitating the process and how to enable others to solve complex problems.

Let’s get started!

How do you identify problems?

How do you identify the right solution.

- Tips for more effective problem-solving

Complete problem-solving methods

- Problem-solving techniques to identify and analyze problems

- Problem-solving techniques for developing solutions

Problem-solving warm-up activities

Closing activities for a problem-solving process.

Before you can move towards finding the right solution for a given problem, you first need to identify and define the problem you wish to solve.

Here, you want to clearly articulate what the problem is and allow your group to do the same. Remember that everyone in a group is likely to have differing perspectives and alignment is necessary in order to help the group move forward.

Identifying a problem accurately also requires that all members of a group are able to contribute their views in an open and safe manner. It can be scary for people to stand up and contribute, especially if the problems or challenges are emotive or personal in nature. Be sure to try and create a psychologically safe space for these kinds of discussions.

Remember that problem analysis and further discussion are also important. Not taking the time to fully analyze and discuss a challenge can result in the development of solutions that are not fit for purpose or do not address the underlying issue.

Successfully identifying and then analyzing a problem means facilitating a group through activities designed to help them clearly and honestly articulate their thoughts and produce usable insight.

With this data, you might then produce a problem statement that clearly describes the problem you wish to be addressed and also state the goal of any process you undertake to tackle this issue.

Finding solutions is the end goal of any process. Complex organizational challenges can only be solved with an appropriate solution but discovering them requires using the right problem-solving tool.

After you’ve explored a problem and discussed ideas, you need to help a team discuss and choose the right solution. Consensus tools and methods such as those below help a group explore possible solutions before then voting for the best. They’re a great way to tap into the collective intelligence of the group for great results!

Remember that the process is often iterative. Great problem solvers often roadtest a viable solution in a measured way to see what works too. While you might not get the right solution on your first try, the methods below help teams land on the most likely to succeed solution while also holding space for improvement.

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . A well-structured workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

In SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Tips for more effective problem solving

Problem-solving activities are only one part of the puzzle. While a great method can help unlock your team’s ability to solve problems, without a thoughtful approach and strong facilitation the solutions may not be fit for purpose.

Let’s take a look at some problem-solving tips you can apply to any process to help it be a success!

Clearly define the problem

Jumping straight to solutions can be tempting, though without first clearly articulating a problem, the solution might not be the right one. Many of the problem-solving activities below include sections where the problem is explored and clearly defined before moving on.

This is a vital part of the problem-solving process and taking the time to fully define an issue can save time and effort later. A clear definition helps identify irrelevant information and it also ensures that your team sets off on the right track.

Don’t jump to conclusions

It’s easy for groups to exhibit cognitive bias or have preconceived ideas about both problems and potential solutions. Be sure to back up any problem statements or potential solutions with facts, research, and adequate forethought.

The best techniques ask participants to be methodical and challenge preconceived notions. Make sure you give the group enough time and space to collect relevant information and consider the problem in a new way. By approaching the process with a clear, rational mindset, you’ll often find that better solutions are more forthcoming.

Try different approaches

Problems come in all shapes and sizes and so too should the methods you use to solve them. If you find that one approach isn’t yielding results and your team isn’t finding different solutions, try mixing it up. You’ll be surprised at how using a new creative activity can unblock your team and generate great solutions.

Don’t take it personally

Depending on the nature of your team or organizational problems, it’s easy for conversations to get heated. While it’s good for participants to be engaged in the discussions, ensure that emotions don’t run too high and that blame isn’t thrown around while finding solutions.

You’re all in it together, and even if your team or area is seeing problems, that isn’t necessarily a disparagement of you personally. Using facilitation skills to manage group dynamics is one effective method of helping conversations be more constructive.

Get the right people in the room

Your problem-solving method is often only as effective as the group using it. Getting the right people on the job and managing the number of people present is important too!

If the group is too small, you may not get enough different perspectives to effectively solve a problem. If the group is too large, you can go round and round during the ideation stages.

Creating the right group makeup is also important in ensuring you have the necessary expertise and skillset to both identify and follow up on potential solutions. Carefully consider who to include at each stage to help ensure your problem-solving method is followed and positioned for success.

Document everything

The best solutions can take refinement, iteration, and reflection to come out. Get into a habit of documenting your process in order to keep all the learnings from the session and to allow ideas to mature and develop. Many of the methods below involve the creation of documents or shared resources. Be sure to keep and share these so everyone can benefit from the work done!

Bring a facilitator

Facilitation is all about making group processes easier. With a subject as potentially emotive and important as problem-solving, having an impartial third party in the form of a facilitator can make all the difference in finding great solutions and keeping the process moving. Consider bringing a facilitator to your problem-solving session to get better results and generate meaningful solutions!

Develop your problem-solving skills

It takes time and practice to be an effective problem solver. While some roles or participants might more naturally gravitate towards problem-solving, it can take development and planning to help everyone create better solutions.

You might develop a training program, run a problem-solving workshop or simply ask your team to practice using the techniques below. Check out our post on problem-solving skills to see how you and your group can develop the right mental process and be more resilient to issues too!

Design a great agenda

Workshops are a great format for solving problems. With the right approach, you can focus a group and help them find the solutions to their own problems. But designing a process can be time-consuming and finding the right activities can be difficult.

Check out our workshop planning guide to level-up your agenda design and start running more effective workshops. Need inspiration? Check out templates designed by expert facilitators to help you kickstart your process!

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

- Six Thinking Hats

- Lightning Decision Jam

- Problem Definition Process

- Discovery & Action Dialogue

Design Sprint 2.0

- Open Space Technology

1. Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

2. Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly The problem with anything that requires creative thinking is that it’s easy to get lost—lose focus and fall into the trap of having useless, open-ended, unstructured discussions. Here’s the most effective solution I’ve found: Replace all open, unstructured discussion with a clear process. What to use this exercise for: Anything which requires a group of people to make decisions, solve problems or discuss challenges. It’s always good to frame an LDJ session with a broad topic, here are some examples: The conversion flow of our checkout Our internal design process How we organise events Keeping up with our competition Improving sales flow

3. Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

4. The 5 Whys

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

5. World Cafe

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

6. Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

7. Design Sprint 2.0

Want to see how a team can solve big problems and move forward with prototyping and testing solutions in a few days? The Design Sprint 2.0 template from Jake Knapp, author of Sprint, is a complete agenda for a with proven results.

Developing the right agenda can involve difficult but necessary planning. Ensuring all the correct steps are followed can also be stressful or time-consuming depending on your level of experience.

Use this complete 4-day workshop template if you are finding there is no obvious solution to your challenge and want to focus your team around a specific problem that might require a shortcut to launching a minimum viable product or waiting for the organization-wide implementation of a solution.

8. Open space technology

Open space technology- developed by Harrison Owen – creates a space where large groups are invited to take ownership of their problem solving and lead individual sessions. Open space technology is a great format when you have a great deal of expertise and insight in the room and want to allow for different takes and approaches on a particular theme or problem you need to be solved.

Start by bringing your participants together to align around a central theme and focus their efforts. Explain the ground rules to help guide the problem-solving process and then invite members to identify any issue connecting to the central theme that they are interested in and are prepared to take responsibility for.

Once participants have decided on their approach to the core theme, they write their issue on a piece of paper, announce it to the group, pick a session time and place, and post the paper on the wall. As the wall fills up with sessions, the group is then invited to join the sessions that interest them the most and which they can contribute to, then you’re ready to begin!

Everyone joins the problem-solving group they’ve signed up to, record the discussion and if appropriate, findings can then be shared with the rest of the group afterward.

Open Space Technology #action plan #idea generation #problem solving #issue analysis #large group #online #remote-friendly Open Space is a methodology for large groups to create their agenda discerning important topics for discussion, suitable for conferences, community gatherings and whole system facilitation

Techniques to identify and analyze problems

Using a problem-solving method to help a team identify and analyze a problem can be a quick and effective addition to any workshop or meeting.

While further actions are always necessary, you can generate momentum and alignment easily, and these activities are a great place to get started.

We’ve put together this list of techniques to help you and your team with problem identification, analysis, and discussion that sets the foundation for developing effective solutions.

Let’s take a look!

- The Creativity Dice

- Fishbone Analysis

- Problem Tree

- SWOT Analysis

- Agreement-Certainty Matrix

- The Journalistic Six

- LEGO Challenge

- What, So What, Now What?

- Journalists

Individual and group perspectives are incredibly important, but what happens if people are set in their minds and need a change of perspective in order to approach a problem more effectively?

Flip It is a method we love because it is both simple to understand and run, and allows groups to understand how their perspectives and biases are formed.

Participants in Flip It are first invited to consider concerns, issues, or problems from a perspective of fear and write them on a flip chart. Then, the group is asked to consider those same issues from a perspective of hope and flip their understanding.

No problem and solution is free from existing bias and by changing perspectives with Flip It, you can then develop a problem solving model quickly and effectively.

Flip It! #gamestorming #problem solving #action Often, a change in a problem or situation comes simply from a change in our perspectives. Flip It! is a quick game designed to show players that perspectives are made, not born.

10. The Creativity Dice

One of the most useful problem solving skills you can teach your team is of approaching challenges with creativity, flexibility, and openness. Games like The Creativity Dice allow teams to overcome the potential hurdle of too much linear thinking and approach the process with a sense of fun and speed.

In The Creativity Dice, participants are organized around a topic and roll a dice to determine what they will work on for a period of 3 minutes at a time. They might roll a 3 and work on investigating factual information on the chosen topic. They might roll a 1 and work on identifying the specific goals, standards, or criteria for the session.

Encouraging rapid work and iteration while asking participants to be flexible are great skills to cultivate. Having a stage for idea incubation in this game is also important. Moments of pause can help ensure the ideas that are put forward are the most suitable.

The Creativity Dice #creativity #problem solving #thiagi #issue analysis Too much linear thinking is hazardous to creative problem solving. To be creative, you should approach the problem (or the opportunity) from different points of view. You should leave a thought hanging in mid-air and move to another. This skipping around prevents premature closure and lets your brain incubate one line of thought while you consciously pursue another.

11. Fishbone Analysis

Organizational or team challenges are rarely simple, and it’s important to remember that one problem can be an indication of something that goes deeper and may require further consideration to be solved.

Fishbone Analysis helps groups to dig deeper and understand the origins of a problem. It’s a great example of a root cause analysis method that is simple for everyone on a team to get their head around.

Participants in this activity are asked to annotate a diagram of a fish, first adding the problem or issue to be worked on at the head of a fish before then brainstorming the root causes of the problem and adding them as bones on the fish.

Using abstractions such as a diagram of a fish can really help a team break out of their regular thinking and develop a creative approach.

Fishbone Analysis #problem solving ##root cause analysis #decision making #online facilitation A process to help identify and understand the origins of problems, issues or observations.

12. Problem Tree

Encouraging visual thinking can be an essential part of many strategies. By simply reframing and clarifying problems, a group can move towards developing a problem solving model that works for them.

In Problem Tree, groups are asked to first brainstorm a list of problems – these can be design problems, team problems or larger business problems – and then organize them into a hierarchy. The hierarchy could be from most important to least important or abstract to practical, though the key thing with problem solving games that involve this aspect is that your group has some way of managing and sorting all the issues that are raised.

Once you have a list of problems that need to be solved and have organized them accordingly, you’re then well-positioned for the next problem solving steps.

Problem tree #define intentions #create #design #issue analysis A problem tree is a tool to clarify the hierarchy of problems addressed by the team within a design project; it represents high level problems or related sublevel problems.

13. SWOT Analysis

Chances are you’ve heard of the SWOT Analysis before. This problem-solving method focuses on identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats is a tried and tested method for both individuals and teams.

Start by creating a desired end state or outcome and bare this in mind – any process solving model is made more effective by knowing what you are moving towards. Create a quadrant made up of the four categories of a SWOT analysis and ask participants to generate ideas based on each of those quadrants.

Once you have those ideas assembled in their quadrants, cluster them together based on their affinity with other ideas. These clusters are then used to facilitate group conversations and move things forward.

SWOT analysis #gamestorming #problem solving #action #meeting facilitation The SWOT Analysis is a long-standing technique of looking at what we have, with respect to the desired end state, as well as what we could improve on. It gives us an opportunity to gauge approaching opportunities and dangers, and assess the seriousness of the conditions that affect our future. When we understand those conditions, we can influence what comes next.

14. Agreement-Certainty Matrix

Not every problem-solving approach is right for every challenge, and deciding on the right method for the challenge at hand is a key part of being an effective team.

The Agreement Certainty matrix helps teams align on the nature of the challenges facing them. By sorting problems from simple to chaotic, your team can understand what methods are suitable for each problem and what they can do to ensure effective results.

If you are already using Liberating Structures techniques as part of your problem-solving strategy, the Agreement-Certainty Matrix can be an invaluable addition to your process. We’ve found it particularly if you are having issues with recurring problems in your organization and want to go deeper in understanding the root cause.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Organizing and charting a team’s progress can be important in ensuring its success. SQUID (Sequential Question and Insight Diagram) is a great model that allows a team to effectively switch between giving questions and answers and develop the skills they need to stay on track throughout the process.

Begin with two different colored sticky notes – one for questions and one for answers – and with your central topic (the head of the squid) on the board. Ask the group to first come up with a series of questions connected to their best guess of how to approach the topic. Ask the group to come up with answers to those questions, fix them to the board and connect them with a line. After some discussion, go back to question mode by responding to the generated answers or other points on the board.

It’s rewarding to see a diagram grow throughout the exercise, and a completed SQUID can provide a visual resource for future effort and as an example for other teams.

SQUID #gamestorming #project planning #issue analysis #problem solving When exploring an information space, it’s important for a group to know where they are at any given time. By using SQUID, a group charts out the territory as they go and can navigate accordingly. SQUID stands for Sequential Question and Insight Diagram.

16. Speed Boat

To continue with our nautical theme, Speed Boat is a short and sweet activity that can help a team quickly identify what employees, clients or service users might have a problem with and analyze what might be standing in the way of achieving a solution.

Methods that allow for a group to make observations, have insights and obtain those eureka moments quickly are invaluable when trying to solve complex problems.

In Speed Boat, the approach is to first consider what anchors and challenges might be holding an organization (or boat) back. Bonus points if you are able to identify any sharks in the water and develop ideas that can also deal with competitors!

Speed Boat #gamestorming #problem solving #action Speedboat is a short and sweet way to identify what your employees or clients don’t like about your product/service or what’s standing in the way of a desired goal.

17. The Journalistic Six

Some of the most effective ways of solving problems is by encouraging teams to be more inclusive and diverse in their thinking.

Based on the six key questions journalism students are taught to answer in articles and news stories, The Journalistic Six helps create teams to see the whole picture. By using who, what, when, where, why, and how to facilitate the conversation and encourage creative thinking, your team can make sure that the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the are covered exhaustively and thoughtfully. Reporter’s notebook and dictaphone optional.

The Journalistic Six – Who What When Where Why How #idea generation #issue analysis #problem solving #online #creative thinking #remote-friendly A questioning method for generating, explaining, investigating ideas.

18. LEGO Challenge

Now for an activity that is a little out of the (toy) box. LEGO Serious Play is a facilitation methodology that can be used to improve creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

The LEGO Challenge includes giving each member of the team an assignment that is hidden from the rest of the group while they create a structure without speaking.

What the LEGO challenge brings to the table is a fun working example of working with stakeholders who might not be on the same page to solve problems. Also, it’s LEGO! Who doesn’t love LEGO!

LEGO Challenge #hyperisland #team A team-building activity in which groups must work together to build a structure out of LEGO, but each individual has a secret “assignment” which makes the collaborative process more challenging. It emphasizes group communication, leadership dynamics, conflict, cooperation, patience and problem solving strategy.

19. What, So What, Now What?

If not carefully managed, the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the problem-solving process can actually create more problems and misunderstandings.

The What, So What, Now What? problem-solving activity is designed to help collect insights and move forward while also eliminating the possibility of disagreement when it comes to identifying, clarifying, and analyzing organizational or work problems.

Facilitation is all about bringing groups together so that might work on a shared goal and the best problem-solving strategies ensure that teams are aligned in purpose, if not initially in opinion or insight.

Throughout the three steps of this game, you give everyone on a team to reflect on a problem by asking what happened, why it is important, and what actions should then be taken.

This can be a great activity for bringing our individual perceptions about a problem or challenge and contextualizing it in a larger group setting. This is one of the most important problem-solving skills you can bring to your organization.

W³ – What, So What, Now What? #issue analysis #innovation #liberating structures You can help groups reflect on a shared experience in a way that builds understanding and spurs coordinated action while avoiding unproductive conflict. It is possible for every voice to be heard while simultaneously sifting for insights and shaping new direction. Progressing in stages makes this practical—from collecting facts about What Happened to making sense of these facts with So What and finally to what actions logically follow with Now What . The shared progression eliminates most of the misunderstandings that otherwise fuel disagreements about what to do. Voila!

20. Journalists

Problem analysis can be one of the most important and decisive stages of all problem-solving tools. Sometimes, a team can become bogged down in the details and are unable to move forward.

Journalists is an activity that can avoid a group from getting stuck in the problem identification or problem analysis stages of the process.

In Journalists, the group is invited to draft the front page of a fictional newspaper and figure out what stories deserve to be on the cover and what headlines those stories will have. By reframing how your problems and challenges are approached, you can help a team move productively through the process and be better prepared for the steps to follow.

Journalists #vision #big picture #issue analysis #remote-friendly This is an exercise to use when the group gets stuck in details and struggles to see the big picture. Also good for defining a vision.

Problem-solving techniques for developing solutions

The success of any problem-solving process can be measured by the solutions it produces. After you’ve defined the issue, explored existing ideas, and ideated, it’s time to narrow down to the correct solution.

Use these problem-solving techniques when you want to help your team find consensus, compare possible solutions, and move towards taking action on a particular problem.

- Improved Solutions

- Four-Step Sketch

- 15% Solutions

- How-Now-Wow matrix

- Impact Effort Matrix

21. Mindspin

Brainstorming is part of the bread and butter of the problem-solving process and all problem-solving strategies benefit from getting ideas out and challenging a team to generate solutions quickly.

With Mindspin, participants are encouraged not only to generate ideas but to do so under time constraints and by slamming down cards and passing them on. By doing multiple rounds, your team can begin with a free generation of possible solutions before moving on to developing those solutions and encouraging further ideation.

This is one of our favorite problem-solving activities and can be great for keeping the energy up throughout the workshop. Remember the importance of helping people become engaged in the process – energizing problem-solving techniques like Mindspin can help ensure your team stays engaged and happy, even when the problems they’re coming together to solve are complex.

MindSpin #teampedia #idea generation #problem solving #action A fast and loud method to enhance brainstorming within a team. Since this activity has more than round ideas that are repetitive can be ruled out leaving more creative and innovative answers to the challenge.

22. Improved Solutions

After a team has successfully identified a problem and come up with a few solutions, it can be tempting to call the work of the problem-solving process complete. That said, the first solution is not necessarily the best, and by including a further review and reflection activity into your problem-solving model, you can ensure your group reaches the best possible result.

One of a number of problem-solving games from Thiagi Group, Improved Solutions helps you go the extra mile and develop suggested solutions with close consideration and peer review. By supporting the discussion of several problems at once and by shifting team roles throughout, this problem-solving technique is a dynamic way of finding the best solution.

Improved Solutions #creativity #thiagi #problem solving #action #team You can improve any solution by objectively reviewing its strengths and weaknesses and making suitable adjustments. In this creativity framegame, you improve the solutions to several problems. To maintain objective detachment, you deal with a different problem during each of six rounds and assume different roles (problem owner, consultant, basher, booster, enhancer, and evaluator) during each round. At the conclusion of the activity, each player ends up with two solutions to her problem.

23. Four Step Sketch

Creative thinking and visual ideation does not need to be confined to the opening stages of your problem-solving strategies. Exercises that include sketching and prototyping on paper can be effective at the solution finding and development stage of the process, and can be great for keeping a team engaged.

By going from simple notes to a crazy 8s round that involves rapidly sketching 8 variations on their ideas before then producing a final solution sketch, the group is able to iterate quickly and visually. Problem-solving techniques like Four-Step Sketch are great if you have a group of different thinkers and want to change things up from a more textual or discussion-based approach.

Four-Step Sketch #design sprint #innovation #idea generation #remote-friendly The four-step sketch is an exercise that helps people to create well-formed concepts through a structured process that includes: Review key information Start design work on paper, Consider multiple variations , Create a detailed solution . This exercise is preceded by a set of other activities allowing the group to clarify the challenge they want to solve. See how the Four Step Sketch exercise fits into a Design Sprint

24. 15% Solutions

Some problems are simpler than others and with the right problem-solving activities, you can empower people to take immediate actions that can help create organizational change.

Part of the liberating structures toolkit, 15% solutions is a problem-solving technique that focuses on finding and implementing solutions quickly. A process of iterating and making small changes quickly can help generate momentum and an appetite for solving complex problems.

Problem-solving strategies can live and die on whether people are onboard. Getting some quick wins is a great way of getting people behind the process.

It can be extremely empowering for a team to realize that problem-solving techniques can be deployed quickly and easily and delineate between things they can positively impact and those things they cannot change.

15% Solutions #action #liberating structures #remote-friendly You can reveal the actions, however small, that everyone can do immediately. At a minimum, these will create momentum, and that may make a BIG difference. 15% Solutions show that there is no reason to wait around, feel powerless, or fearful. They help people pick it up a level. They get individuals and the group to focus on what is within their discretion instead of what they cannot change. With a very simple question, you can flip the conversation to what can be done and find solutions to big problems that are often distributed widely in places not known in advance. Shifting a few grains of sand may trigger a landslide and change the whole landscape.

25. How-Now-Wow Matrix

The problem-solving process is often creative, as complex problems usually require a change of thinking and creative response in order to find the best solutions. While it’s common for the first stages to encourage creative thinking, groups can often gravitate to familiar solutions when it comes to the end of the process.

When selecting solutions, you don’t want to lose your creative energy! The How-Now-Wow Matrix from Gamestorming is a great problem-solving activity that enables a group to stay creative and think out of the box when it comes to selecting the right solution for a given problem.

Problem-solving techniques that encourage creative thinking and the ideation and selection of new solutions can be the most effective in organisational change. Give the How-Now-Wow Matrix a go, and not just for how pleasant it is to say out loud.

How-Now-Wow Matrix #gamestorming #idea generation #remote-friendly When people want to develop new ideas, they most often think out of the box in the brainstorming or divergent phase. However, when it comes to convergence, people often end up picking ideas that are most familiar to them. This is called a ‘creative paradox’ or a ‘creadox’. The How-Now-Wow matrix is an idea selection tool that breaks the creadox by forcing people to weigh each idea on 2 parameters.

26. Impact and Effort Matrix

All problem-solving techniques hope to not only find solutions to a given problem or challenge but to find the best solution. When it comes to finding a solution, groups are invited to put on their decision-making hats and really think about how a proposed idea would work in practice.

The Impact and Effort Matrix is one of the problem-solving techniques that fall into this camp, empowering participants to first generate ideas and then categorize them into a 2×2 matrix based on impact and effort.

Activities that invite critical thinking while remaining simple are invaluable. Use the Impact and Effort Matrix to move from ideation and towards evaluating potential solutions before then committing to them.

Impact and Effort Matrix #gamestorming #decision making #action #remote-friendly In this decision-making exercise, possible actions are mapped based on two factors: effort required to implement and potential impact. Categorizing ideas along these lines is a useful technique in decision making, as it obliges contributors to balance and evaluate suggested actions before committing to them.

27. Dotmocracy

If you’ve followed each of the problem-solving steps with your group successfully, you should move towards the end of your process with heaps of possible solutions developed with a specific problem in mind. But how do you help a group go from ideation to putting a solution into action?

Dotmocracy – or Dot Voting -is a tried and tested method of helping a team in the problem-solving process make decisions and put actions in place with a degree of oversight and consensus.

One of the problem-solving techniques that should be in every facilitator’s toolbox, Dot Voting is fast and effective and can help identify the most popular and best solutions and help bring a group to a decision effectively.

Dotmocracy #action #decision making #group prioritization #hyperisland #remote-friendly Dotmocracy is a simple method for group prioritization or decision-making. It is not an activity on its own, but a method to use in processes where prioritization or decision-making is the aim. The method supports a group to quickly see which options are most popular or relevant. The options or ideas are written on post-its and stuck up on a wall for the whole group to see. Each person votes for the options they think are the strongest, and that information is used to inform a decision.

All facilitators know that warm-ups and icebreakers are useful for any workshop or group process. Problem-solving workshops are no different.

Use these problem-solving techniques to warm up a group and prepare them for the rest of the process. Activating your group by tapping into some of the top problem-solving skills can be one of the best ways to see great outcomes from your session.

- Check-in/Check-out

- Doodling Together

- Show and Tell

- Constellations

- Draw a Tree

28. Check-in / Check-out

Solid processes are planned from beginning to end, and the best facilitators know that setting the tone and establishing a safe, open environment can be integral to a successful problem-solving process.

Check-in / Check-out is a great way to begin and/or bookend a problem-solving workshop. Checking in to a session emphasizes that everyone will be seen, heard, and expected to contribute.

If you are running a series of meetings, setting a consistent pattern of checking in and checking out can really help your team get into a groove. We recommend this opening-closing activity for small to medium-sized groups though it can work with large groups if they’re disciplined!

Check-in / Check-out #team #opening #closing #hyperisland #remote-friendly Either checking-in or checking-out is a simple way for a team to open or close a process, symbolically and in a collaborative way. Checking-in/out invites each member in a group to be present, seen and heard, and to express a reflection or a feeling. Checking-in emphasizes presence, focus and group commitment; checking-out emphasizes reflection and symbolic closure.

29. Doodling Together

Thinking creatively and not being afraid to make suggestions are important problem-solving skills for any group or team, and warming up by encouraging these behaviors is a great way to start.

Doodling Together is one of our favorite creative ice breaker games – it’s quick, effective, and fun and can make all following problem-solving steps easier by encouraging a group to collaborate visually. By passing cards and adding additional items as they go, the workshop group gets into a groove of co-creation and idea development that is crucial to finding solutions to problems.

Doodling Together #collaboration #creativity #teamwork #fun #team #visual methods #energiser #icebreaker #remote-friendly Create wild, weird and often funny postcards together & establish a group’s creative confidence.

30. Show and Tell

You might remember some version of Show and Tell from being a kid in school and it’s a great problem-solving activity to kick off a session.

Asking participants to prepare a little something before a workshop by bringing an object for show and tell can help them warm up before the session has even begun! Games that include a physical object can also help encourage early engagement before moving onto more big-picture thinking.

By asking your participants to tell stories about why they chose to bring a particular item to the group, you can help teams see things from new perspectives and see both differences and similarities in the way they approach a topic. Great groundwork for approaching a problem-solving process as a team!

Show and Tell #gamestorming #action #opening #meeting facilitation Show and Tell taps into the power of metaphors to reveal players’ underlying assumptions and associations around a topic The aim of the game is to get a deeper understanding of stakeholders’ perspectives on anything—a new project, an organizational restructuring, a shift in the company’s vision or team dynamic.

31. Constellations

Who doesn’t love stars? Constellations is a great warm-up activity for any workshop as it gets people up off their feet, energized, and ready to engage in new ways with established topics. It’s also great for showing existing beliefs, biases, and patterns that can come into play as part of your session.

Using warm-up games that help build trust and connection while also allowing for non-verbal responses can be great for easing people into the problem-solving process and encouraging engagement from everyone in the group. Constellations is great in large spaces that allow for movement and is definitely a practical exercise to allow the group to see patterns that are otherwise invisible.

Constellations #trust #connection #opening #coaching #patterns #system Individuals express their response to a statement or idea by standing closer or further from a central object. Used with teams to reveal system, hidden patterns, perspectives.

32. Draw a Tree

Problem-solving games that help raise group awareness through a central, unifying metaphor can be effective ways to warm-up a group in any problem-solving model.

Draw a Tree is a simple warm-up activity you can use in any group and which can provide a quick jolt of energy. Start by asking your participants to draw a tree in just 45 seconds – they can choose whether it will be abstract or realistic.

Once the timer is up, ask the group how many people included the roots of the tree and use this as a means to discuss how we can ignore important parts of any system simply because they are not visible.

All problem-solving strategies are made more effective by thinking of problems critically and by exposing things that may not normally come to light. Warm-up games like Draw a Tree are great in that they quickly demonstrate some key problem-solving skills in an accessible and effective way.

Draw a Tree #thiagi #opening #perspectives #remote-friendly With this game you can raise awarness about being more mindful, and aware of the environment we live in.

Each step of the problem-solving workshop benefits from an intelligent deployment of activities, games, and techniques. Bringing your session to an effective close helps ensure that solutions are followed through on and that you also celebrate what has been achieved.

Here are some problem-solving activities you can use to effectively close a workshop or meeting and ensure the great work you’ve done can continue afterward.

- One Breath Feedback

- Who What When Matrix

- Response Cards

How do I conclude a problem-solving process?

All good things must come to an end. With the bulk of the work done, it can be tempting to conclude your workshop swiftly and without a moment to debrief and align. This can be problematic in that it doesn’t allow your team to fully process the results or reflect on the process.

At the end of an effective session, your team will have gone through a process that, while productive, can be exhausting. It’s important to give your group a moment to take a breath, ensure that they are clear on future actions, and provide short feedback before leaving the space.

The primary purpose of any problem-solving method is to generate solutions and then implement them. Be sure to take the opportunity to ensure everyone is aligned and ready to effectively implement the solutions you produced in the workshop.

Remember that every process can be improved and by giving a short moment to collect feedback in the session, you can further refine your problem-solving methods and see further success in the future too.

33. One Breath Feedback

Maintaining attention and focus during the closing stages of a problem-solving workshop can be tricky and so being concise when giving feedback can be important. It’s easy to incur “death by feedback” should some team members go on for too long sharing their perspectives in a quick feedback round.

One Breath Feedback is a great closing activity for workshops. You give everyone an opportunity to provide feedback on what they’ve done but only in the space of a single breath. This keeps feedback short and to the point and means that everyone is encouraged to provide the most important piece of feedback to them.

One breath feedback #closing #feedback #action This is a feedback round in just one breath that excels in maintaining attention: each participants is able to speak during just one breath … for most people that’s around 20 to 25 seconds … unless of course you’ve been a deep sea diver in which case you’ll be able to do it for longer.

34. Who What When Matrix

Matrices feature as part of many effective problem-solving strategies and with good reason. They are easily recognizable, simple to use, and generate results.

The Who What When Matrix is a great tool to use when closing your problem-solving session by attributing a who, what and when to the actions and solutions you have decided upon. The resulting matrix is a simple, easy-to-follow way of ensuring your team can move forward.

Great solutions can’t be enacted without action and ownership. Your problem-solving process should include a stage for allocating tasks to individuals or teams and creating a realistic timeframe for those solutions to be implemented or checked out. Use this method to keep the solution implementation process clear and simple for all involved.

Who/What/When Matrix #gamestorming #action #project planning With Who/What/When matrix, you can connect people with clear actions they have defined and have committed to.

35. Response cards

Group discussion can comprise the bulk of most problem-solving activities and by the end of the process, you might find that your team is talked out!

Providing a means for your team to give feedback with short written notes can ensure everyone is head and can contribute without the need to stand up and talk. Depending on the needs of the group, giving an alternative can help ensure everyone can contribute to your problem-solving model in the way that makes the most sense for them.

Response Cards is a great way to close a workshop if you are looking for a gentle warm-down and want to get some swift discussion around some of the feedback that is raised.

Response Cards #debriefing #closing #structured sharing #questions and answers #thiagi #action It can be hard to involve everyone during a closing of a session. Some might stay in the background or get unheard because of louder participants. However, with the use of Response Cards, everyone will be involved in providing feedback or clarify questions at the end of a session.

Save time and effort discovering the right solutions

A structured problem solving process is a surefire way of solving tough problems, discovering creative solutions and driving organizational change. But how can you design for successful outcomes?

With SessionLab, it’s easy to design engaging workshops that deliver results. Drag, drop and reorder blocks to build your agenda. When you make changes or update your agenda, your session timing adjusts automatically , saving you time on manual adjustments.

Collaborating with stakeholders or clients? Share your agenda with a single click and collaborate in real-time. No more sending documents back and forth over email.

Explore how to use SessionLab to design effective problem solving workshops or watch this five minute video to see the planner in action!

Over to you

The problem-solving process can often be as complicated and multifaceted as the problems they are set-up to solve. With the right problem-solving techniques and a mix of creative exercises designed to guide discussion and generate purposeful ideas, we hope we’ve given you the tools to find the best solutions as simply and easily as possible.

Is there a problem-solving technique that you are missing here? Do you have a favorite activity or method you use when facilitating? Let us know in the comments below, we’d love to hear from you!

thank you very much for these excellent techniques

Certainly wonderful article, very detailed. Shared!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Going from a mere idea to a workshop that delivers results for your clients can feel like a daunting task. In this piece, we will shine a light on all the work behind the scenes and help you learn how to plan a workshop from start to finish. On a good day, facilitation can feel like effortless magic, but that is mostly the result of backstage work, foresight, and a lot of careful planning. Read on to learn a step-by-step approach to breaking the process of planning a workshop into small, manageable chunks. The flow starts with the first meeting with a client to define the purposes of a workshop.…

How does learning work? A clever 9-year-old once told me: “I know I am learning something new when I am surprised.” The science of adult learning tells us that, in order to learn new skills (which, unsurprisingly, is harder for adults to do than kids) grown-ups need to first get into a specific headspace. In a business, this approach is often employed in a training session where employees learn new skills or work on professional development. But how do you ensure your training is effective? In this guide, we'll explore how to create an effective training session plan and run engaging training sessions. As team leader, project manager, or consultant,…

Effective online tools are a necessity for smooth and engaging virtual workshops and meetings. But how do you choose the right ones? Do you sometimes feel that the good old pen and paper or MS Office toolkit and email leaves you struggling to stay on top of managing and delivering your workshop? Fortunately, there are plenty of online tools to make your life easier when you need to facilitate a meeting and lead workshops. In this post, we’ll share our favorite online tools you can use to make your job as a facilitator easier. In fact, there are plenty of free online workshop tools and meeting facilitation software you can…

Design your next workshop with SessionLab

Join the 150,000 facilitators using SessionLab

Sign up for free

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Six problem-solving mindsets for very uncertain times