Creative Writing

Creative Writing Initiatives

Initiatives as of february 2021.

- We are, with the support of the Lewis Center and the Office of the Dean of Faculty, in the process of making tenured as well as tenure-track hires in order to further diversify our faculty.

- We will hold a town-hall meeting designed for CWR faculty, students, and staff at least annually, preceded by a training/lecture/teach-in by an invited writer/teacher that centers BIPOC experiences and anti-racism, and facilitated by that guest.

- We will redouble our collaboration with existing BIPOC writers’ reading series in other departments, programs, and centers at the University, looking for opportunities to co-sponsor and cross-promote these readings, and continue to feature BIPOC writers in the two reading series organized by our program.

- The former Committee on Race and the Arts has been replaced by the LCA Climate and Inclusion Committee. This committee plans to offer regular reports of its activities and to make its meetings open to any LCA community members on a regular basis.The Creative Writing Program will stay abreast of the Climate and Inclusion Committee and its activities.

- In cooperation with the Lewis Center, we will reach out to students through programs, centers, and affinity groups in advance of every application and registration deadline each semester, in order to publicize our offerings more widely.

- We will make our application process transparent and are in the process of revising our application guidelines.

- As we have done for the past 5 years, we will offer at least one course that focuses on writing and race each year, which will be open to beginning as well as advanced students.. We will promote these classes vigorously and ask the registrar to make them more apparent to students.

- We will actively work with African American Studies, Program in Latin American Studies, and Asian American Studies along with Princeton Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative to cross-list courses and incorporate what we learn from these programs, departments, and initiatives.

- We will work with residential college(s) to explore the possibility of establishing a writing/study room on campus with a library dedicated to the works of BIPOC authors.

- We will offer a program each year that brings publisher(s), agent(s) and writers to speak with current students on publishing and ethics.

- Professor Rowan Ricardo Phillips is offering a one-session intensive this spring Co-presented by the LCA and the Center for Career Development focusing on different careers or ways to make a living as a write and practical life management tips to consider as students build a writing career. We will also develop and offer a writing careers panel that includes but is not limited to MFA programs.

- With the Trenton Public Library, where we already have an established tie, we will establish a program that enables current students to offer workshop(s) with high school students – these may be in Spanish or English.

- In coordination with the Lewis Center, we are creating a network of mentors, which may include alumni who identify as BIPOC, who are committed to diversity and inclusion.

- We will make available—to all faculty—regular anti-racist trainings by an outside thinker about creative writing and anti-racist practices.

- We are in the process of compiling inclusive workshop practices that can be adapted for any CWR course and will convene faculty brown-bag lunch meetings specifically to share BIPOC-centered practices that have worked in our individual classes.

- Suggested classroom practices will be communicated to all new faculty at hire for their own adaptation.

- The Lewis Center has established a completely anonymous portal through which to share thoughts, suggestions, concerns, or comments on classroom experiences . There is also information available on University Title IX and sexual misconduct resources and reporting mechanisms . All faculty will be encouraged to include this information and link in their syllabi.

Receive Lewis Center Events & News Updates

Search form

On the campus creative writing turns 70.

The Lewis Center is celebrating 70 years of creative writing at Princeton with a yearlong series of public readings by award-winning writers who are program alumni or have served on the faculty.

Novelist Robert Stone, formerly a visiting fellow, and poet C.K. Williams, a current member of the faculty, were scheduled to read in November; poet Maxine Kumin and professor and novelist Joyce Carol Oates kicked off the series in October. Reading later this academic year will be novelist Russell Banks and his wife, the poet Chase Twichell; poet W.S. Merwin ’48; novelist Mona Simpson; and current faculty members Chang-rae Lee and Jeffrey Eugenides. Each session includes a brief reading by a current student.

Princeton’s creative writing program — which has produced such noted contemporary writers as novelists Jonathan Safran Foer ’99 and Jodi Picoult ’87 — is “unparalleled,” said Lee, the program’s director. University creative writing programs, he said, usually are created to offer master’s degrees in fine arts. “There are very few places that are constituted as creative writing programs for undergraduates,” he said. Like students in the country’s most famous graduate programs, undergraduates at Princeton participate in small workshops with renowned writers.

Each year more students apply for a spot in one of the program’s workshops in poetry, fiction, translation, and screenwriting than there are places available. To remedy that problem, Lee said, the program increased its hiring of visiting faculty over the last three years, and the number of sections has increased by 50 percent, to about 14 to 16 offerings a semester. This fall, a record 175 students are enrolled in creative writing workshops.

The program started in 1939; at the time, Dean of the College Christian Gauss thought Princeton did little to cultivate writers and other artists. The program’s mission — still true today — was to encourage undergraduates to work in the creative arts under the supervision of professionals. Poet and critic Allen Tate was appointed the first resident fellow in creative writing, and he soon invited another noted poet and critic, Richard P. Blackmur, to assist him. Blackmur took over the program in the 1940s, attracting as teachers a succession of poets, writers, and critics, including John Berryman and Philip Roth. Poet Edmund Keeley ’48, who directed the program from 1966 to 1981, introduced translation courses into the curriculum and pushed for more permanent tenured faculty appointments. More recent faculty members have included Toni Morrison, Edmund White, and Paul Muldoon.

Today, small workshop courses averaging eight to 10 students provide intensive feedback and instruction for both beginners and advanced writers. The workshop format — in which students share their work with other students, read literature, and have individual faculty conferences — was one of Keeley’s innovations. Keeley wanted to expose students to the process of writing and “how writers themselves think about literature and talk about it,” he said. The format drew on student interest in criticism from their peers: Students “like to hear what their contemporaries are thinking,” he said.

To earn a certificate in creative writing, students must produce a creative thesis, and each year 15 to 20 seniors work to complete a novel or collection of short stories, poems, or translations. Some students write two senior theses, if the creative thesis does not fulfill the requirements of the department in which they are concentrating.

Math major Josephine Wolff ’10 is working on a collection of short stories in addition to a thesis for the math department. After “stumbling into” a creative writing workshop her freshman year, Wolff decided to enroll in the program. She said she finds it “thrilling and stressful” working with writers like Oates and Lee because “they care a lot about our writing and they read it very carefully. They take it seriously and comment on it as if it’s important.”

Faculty members benefit from the workshop discussions as well, said Lee, whose novel The Surrendered will be published in March. “I am stimulated by the exuberance and eagerness ... of these young writers,” he said. “It always reminds me what is so exciting about writing and the art of writing.”

Creative Writing Alumni

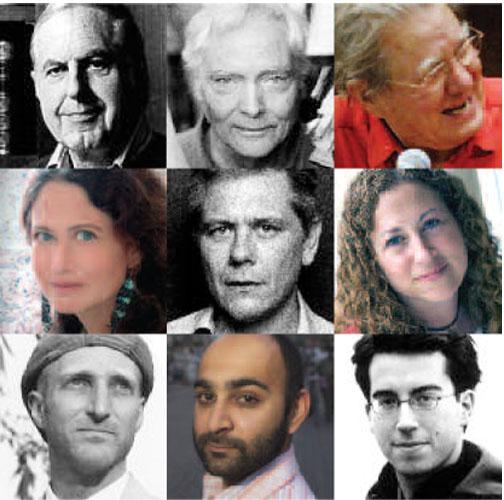

Following is a partial list of writers who took part in the program or studied with its faculty members. They are pictured left to right, starting at the top:

WILLIAM MEREDITH ’40, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet

W.S. MERWIN ’48, celebrated poet and winner of two Pulitzer Prizes

GALWAY KINNELL ’48, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet

JANE HIRSHFIELD ’73, poet; her books include “After”

WALTER KIRN ’83, novelist, critic, and author of the memoir “Lost in the Meritocracy”

JODI PICOULT ’87, best-selling and prolific novelist

JONATHAN AMES ’87, novelist and essayist who has been called “New York’s gonzo scribe”

MOHSIN HAMID ’93, Pakistani-born novelist; his latest book is “The Reluctant Fundamentalist”

JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER ’99, best known for his debut novel, “Everything is Illuminated”

US South Carolina

Recently viewed courses

Recently viewed.

Find Your Dream School

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

- Grad Programs

Creative Writing

Degree Information

Questions to ask yourself when choosing a degree program, career overview, career/licensing requirements, salary information, related links, view all creative writing schools by program.

American Literature

Comparative Literature

English Composition

English Literature

Technical Writing

RELATED GRADUATE PROGRAMS

Acting (M.F.A.)

Arts Education

Drama and Dramatics/Theatre Arts

Playwriting and Screenwriting (M.F.A.)

RELATED CAREERS

Advertising Executive

Book Publishing Professional

SAMPLE CURRICULUM

Creative Non-Fiction

History Of The English Language

History Of The Essay

Modern Fiction And Poetry

Non-Fiction

Theory Of Composition

Theory Of Literature

Featured MBA Programs For You

Connect with business schools around the globe and explore your MBA options.

Best Business Schools

Check out our lists of best on-campus and online MBA programs and find the best program for your career goals.

Explore Graduate Programs For You

Ranked master’s programs around the globe are seeking students like you to join their programs.

Med School Advice

Get medical school application advice, USMLE prep help, learn what to expect in med school and more.

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- Local Offices

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

609-258-2800

Welcome to our 2023-2024 season!

Golda Schultz, Soprano Jonathan Ware, Piano

Apr 8, 7:30pm edt.

Get directions, see parking and accessibility info, download a seating charts, and more.

Bringing world-class music into your life beyond the walls of a concert hall—

ANNOUNCING NEW INITIATIVE:

Virtual programs that connect you to the artists you love, anywhere you are—

New Playlist

Collective Listening Project

We invite students of all ages to discover and deepen a love for live music!

Your support is critical to our future— thank you for making the gift of music.

Through innovative programs presented in an intimate setting, PUC has been committed to making classical music accessible to all since 1894.

We'd love to hear from you!

Creative Reactions Contest

A contest designed to capture the impact of music, as perceived by Princeton University undergraduate and graduate student writers and artists.

Dedicated to the memory of Vera Sharpe Kohn . Hosted by the Student Ambassadors of Princeton University Concerts.

2023-24 Contest

The 2023-24 iteration of the Creative Reactions Contest is organized as part of the Impromptu Challenge .

Engaging with Music: About the Creative Reactions Program

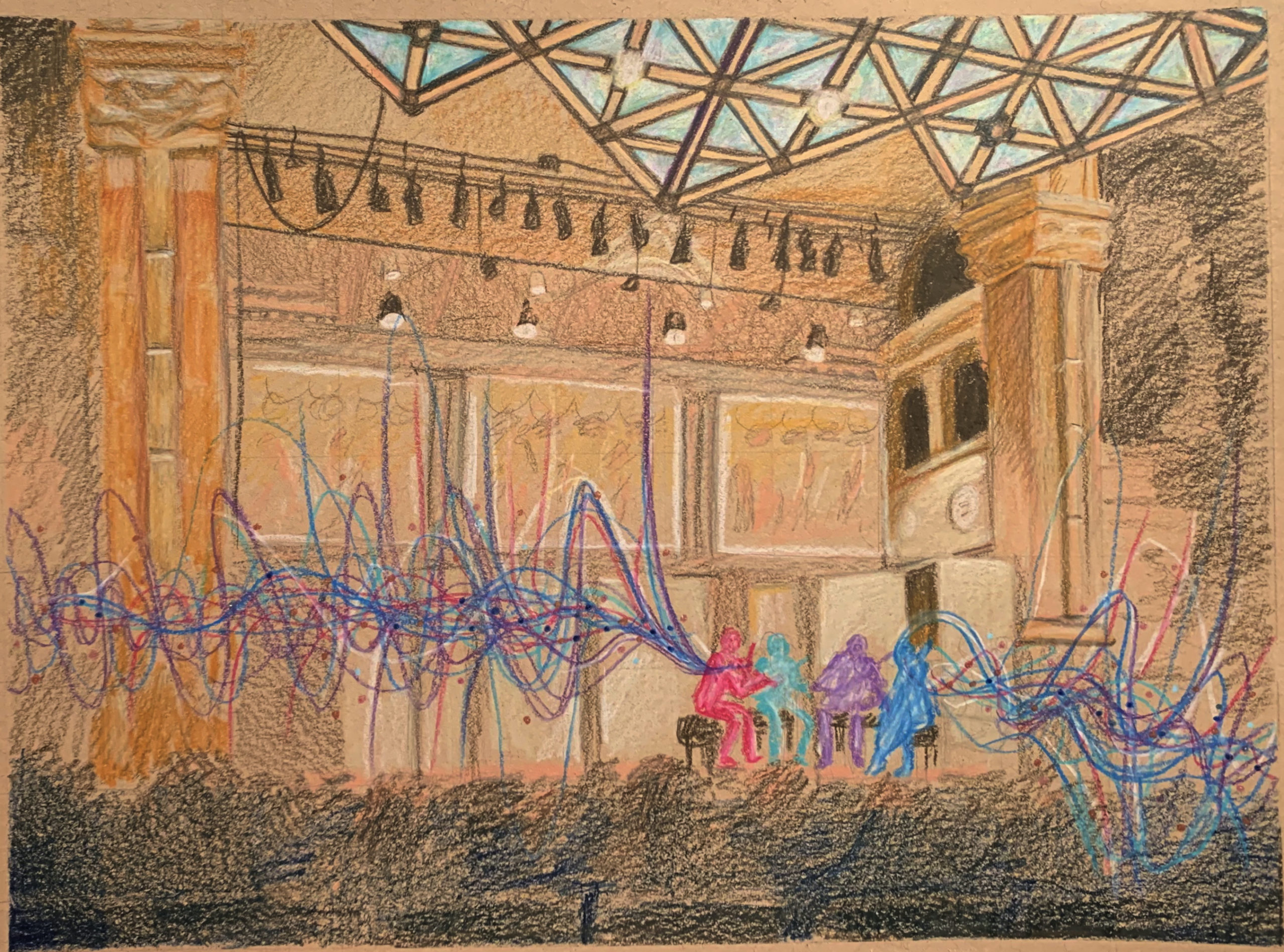

It all started in February 2015, when over one hundred undergraduate and graduate students signed up for the first ever Creative Reactions Writing Contest. Conceived by the Student Ambassadors of Princeton University Concerts, this writing contest gave students a free ticket to attend a Princeton University Concert in the legendary Alexander Hall, in return for a creative written response to the performance—and a chance to win a cash prize. The wonderfully diverse group of submissions brought together judges from many corners of the Princeton community, including professors in the Creative Writing Program and Music Department, the owner of Labyrinth Bookstore, and long-standing community audience members.

The enthusiastic response to this novel initiative made clear that students were eager to extend the concert experience beyond the walls of Alexander Hall, and to share their passion for or curiosity about music with the community at large. Princeton University Concerts (PUC) has developed the Creative Reactions Program in order to provide such an opportunity to all Princeton University students. While continuing the Creative Reactions Contest on an annual basis, now expanded to include other art forms, this program will also present various other means through which students will be able to harness their creative talents in their engagement with music on campus. This includes a student-designed and student-written season brochure, opportunities for writing to be included in printed programs, and more.

Past Winners

First prize winner ($1000).

Youngseo Lee ’25 – “Haikus for Beauty After All”

SECOND PRIZE Winner ($500)

Yaashree Himatsingka ’24 – “Swamp”

HONORABLE MENTION Winner ($250)

Chas Brown ’26 – “Writing in the Dark”

See Winning Submissions

Auhjanae McGee ’23 – “Thank you, Alicia Keys”

SECOND PRIZE WinnerS ($500)

Will Hartman ’25 – “Everything, and What Comes After”

Alejandro Virue , Graduate Student – “Poor Funes … A Dialogue”

First Prize WinnerS ($1000)

Cassandra A. James ’23 – “Hummingbirds: A Pandemic Survival Guide”

Kerem Oktar, Graduate Student – “Everywhere, at the End of Time”

Emily V. Mesev , Graduate Student – “Apocalypse Lullaby”

Honorable Mentions ($250)

Maya Keren ’22 – “Reminder to Self:”

Alexander Kim ’21 – “Dancing about Architecture: Some Selections From, and Commentary On, My Music Listening Diary”

Konstantinos Konstantinou ’22 – “Little Fugue on Covid-19”

Alyssa Cai ’20 – Serene Escape , colored pencil on paper, inspired by a Live Music Meditation with cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

Honorable Mentions ($100)

Nazdar Ayzit ’23 – Untitled , pencil on paper, inspired by an all-Beethoven program performed by violinist Isabelle Faust, cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras, and pianist Alexander Melnikov.

Eliana Gagnon ’23 – Untitled , charcoal/pencil on paper, inspired by a Performances Up Close program with pianist Gabriela Montero.

Sam Melton ’23 – Untitled , colored pencil on paper, inspired by the Calidore String Quartet.

Helen So ’22 – Untitled , digital, inspired by a Performances Up Close program with pianist Gabriela Montero.

Sandy Yang ’22 – Untitled , watercolor, inspired by an all-Beethoven program performed by violinist Isabelle Faust, cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras, and pianist Alexander Melnikov.

VISUAL ARTS CATEGORY

Prize not awarded

CREATIVE WRITING CATEGORY

First Prize Winner ($500)

Crystal Liu ’20 – “It’s Just Llike the Water: A Lyric Essay on Art and Faith” inspired by Gustavo Dudamel’s residency.

Samuel Sebastian Cox ’18 – “Untitled” inspired by the Tenebrae Choir Sang Lee ’18 – “A Couple of Fiddles” inspired by “Shostakovich and the Black Monk: A Russian Fantasy”

Diana Chao ’21 – “Gaita (Gal)ega,” inspired by gaita player Cristina Pato Xin Rong Chua GS – “Interlude,” inspired by “Shostakovich and the Black Monk: A Russian Fantasy” Jason Molesky GS – “Tempest” inspired by violinist Jennifer Koh

First Prize Winners ($500)

Anna Leader ’18 – “love songs between balconies” inspired by Mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton David Ting ’17 – “El barrio(lage) desconocido” inspired by pianist violinist Augustin Hadelich & guitarist Pablo Sáinz-Villegas

Honorable Mentions ($125)

Isabella Bosetti ’18 – “Translation/Aphasia,” inspired by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir Xin Chua GS – “The Future Age,” inspired by the Takács String Quartet Kirit Limperis ’19 – “With the Percussionist,” inspired by percussionist Colin Currie

Anna Leader ’18 – “Untitled,” inspired by the Arcanto String Quartet David Ting ’17 – “Journey Between Worlds,” inspired by pianist David Greilsammer

Second Prize Winners ($250)

Magdalena Collum ’18 – “Ritual, in four parts,” inspired by pianist Igor Levit Emily Tu ’16 – “Voice,” inspired by pianist Igor Levit

First Prize Winner

Susannah Sharpless ’15 – “Space and Time,” inspired by violinist Stefan Jackiw and pianist Anna Polonsky

Second Prize Winners

Trevor Klee ’15 – “Untitled,” inspired by pianist Marc-André Hamelin Lucas Mazzotti ’17 – “Untitled,” inspired by the Brentano String Quartet and Joyce DiDonato

Crafting Creativity: Exploring Princeton University's Creative Spaces

April 1, 2024, gina arnau '26.

As an engineering student with a passion for artcraft, I've always found joy in creating things with my own hands, exploring various methods and techniques to bring my ideas to life. So, when I arrived at Princeton and discovered the wealth of resources available for creative exploration, I was absolutely amazed. From the moment I stepped into the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (MAE) Machine Shop to the countless hours spent in the Studio Lab and makerspace, my journey with Princeton's creative spaces has been nothing short of transformative.

My first experience in the MAE Machine Shop was the MAE 321 Engineering Design course. In the course’s labs, we delved into the art of design and manufacturing, utilizing advanced machinery like milling machines and CNC machines to craft intricate designs. From engineering a flywheel cart and bottle opener, to creating an airplane wing from scratch, the MAE Machine Shop is where imagination meets precision, providing students with hands-on experience and technical expertise.

Another vibrant hub of creativity is the Studio Lab, home of the Council of Science and Technology and a playground for artistic expression and experimentation. Here, students can explore a diverse array of mediums, from traditional embroidery to cutting-edge video game design. Equipped with incredible tools such as 3D printers and laser cutters, the Studio Lab empowers students to turn their ideas into reality. Workshops ranging from cryo painting tote bags to origami engineering foster a culture of collaboration and innovation, inspiring students to push the boundaries of their creativity.

Finally, Princeton's makerspace offers students the chance to delve into a multitude of crafts and technologies. From designing custom stickers to crafting intricate bead jewelry, the makerspace provides a hands-on learning environment where creativity knows no bounds. Students can also rent a variety of tech gadgets, from projectors to VR sets, allowing us to bring their visions to life with professional-grade equipment.

If you're someone who loves getting their hands dirty and bringing ideas to life from scratch, Princeton is the place for you. And for those who've yet to dip their toes into the waters of creation, who knows? Maybe Princeton will be the place where you uncover a newfound hobby.

Related Articles

A look into independent research: the politics junior paper, a day in the life (short film), the p in princeton stands for p/d/f.

French Journal of English Studies

Home Numéros 59 1 - Tisser les liens : voyager, e... 36 Views of Moscow Mountain: Teac...

36 Views of Moscow Mountain: Teaching Travel Writing and Mindfulness in the Tradition of Hokusai and Thoreau

L'auteur américain Henry David Thoreau est un écrivain du voyage qui a rarement quitté sa ville natale de Concorde, Massachusetts, où il a vécu de 1817 à 1862. Son approche du "voyage" consiste à accorder une profonde attention à son environnement ordinaire et à voir le monde à partir de perspectives multiples, comme il l'explique avec subtilité dans Walden (1854). Inspiré par Thoreau et par la célèbre série de gravures du peintre d'estampes japonais Katsushika Hokusai, intitulée 36 vues du Mt. Fuji (1830-32), j'ai fait un cours sur "L'écriture thoreauvienne du voyage" à l'Université de l'Idaho, que j'appelle 36 vues des montagnes de Moscow: ou, Faire un grand voyage — l'esprit et le carnet ouvert — dans un petit lieu . Cet article explore la philosophie et les stratégies pédagogiques de ce cours, qui tente de partager avec les étudiants les vertus d'un regard neuf sur le monde, avec les yeux vraiment ouverts, avec le regard d'un voyageur, en "faisant un grand voyage" à Moscow, Idaho. Les étudiants affinent aussi leurs compétences d'écriture et apprennent les traditions littéraires et artistiques associées au voyage et au sens du lieu.

Index terms

Keywords: , designing a writing class to foster engagement.

1 The signs at the edge of town say, "Entering Moscow, Idaho. Population 25,060." This is a small hamlet in the midst of a sea of rolling hills, where farmers grow varieties of wheat, lentils, peas, and garbanzo beans, irrigated by natural rainfall. Although the town of Moscow has a somewhat cosmopolitan feel because of the presence of the University of Idaho (with its 13,000 students and a few thousand faculty and staff members), elegant restaurants, several bookstores and music stores, and a patchwork of artsy coffee shops on Main Street, the entire mini-metropolis has only about a dozen traffic lights and a single high school. As a professor of creative writing and the environmental humanities at the university, I have long been interested in finding ways to give special focuses to my writing and literature classes that will help my students think about the circumstances of their own lives and find not only academic meaning but personal significance in our subjects. I have recently taught graduate writing workshops on such themes as "The Body" and "Crisis," but when I was given the opportunity recently to teach an undergraduate writing class on Personal and Exploratory Writing, I decided to choose a focus that would bring me—and my students—back to one of the writers who has long been of central interest to me: Henry David Thoreau.

2 One of the courses I have routinely taught during the past six years is Environmental Writing, an undergraduate class that I offer as part of the university's Semester in the Wild Program, a unique undergraduate opportunity that sends a small group of students to study five courses (Ecology, Environmental History, Environmental Writing, Outdoor Leadership and Wilderness Survival, and Wilderness Management and Policy) at a remote research station located in the middle of the largest wilderness area (the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness) in the United States south of Alaska. In "Teaching with Wolves," a recent article about the Semester in the Wild Program, I explained that my goal in the Environmental Writing class is to help the students "synthesize their experience in the wilderness with the content of the various classes" and "to think ahead to their professional lives and their lives as engaged citizens, for which critical thinking and communication skills are so important" (325). A foundational text for the Environmental Writing class is a selection from Thoreau's personal journal, specifically the entries he made October 1-20, 1853, which I collected in the 1993 writing textbook Being in the World: An Environmental Reader for Writers . I ask the students in the Semester in the Wild Program to deeply immerse themselves in Thoreau's precise and colorful descriptions of the physical world that is immediately present to him and, in turn, to engage with their immediate encounters with the world in their wilderness location. Thoreau's entries read like this:

Oct. 4. The maples are reddening, and birches yellowing. The mouse-ear in the shade in the middle of the day, so hoary, looks as if the frost still lay on it. Well it wears the frost. Bumblebees are on the Aster undulates , and gnats are dancing in the air. Oct. 5. The howling of the wind about the house just before a storm to-night sounds extremely like a loon on the pond. How fit! Oct. 6 and 7. Windy. Elms bare. (372)

3 In thinking ahead to my class on Personal and Exploratory Writing, which would be offered on the main campus of the University of Idaho in the fall semester of 2018, I wanted to find a topic that would instill in my students the Thoreauvian spirit of visceral engagement with the world, engagement on the physical, emotional, and philosophical levels, while still allowing my students to remain in the city and live their regular lives as students. It occurred to me that part of what makes Thoreau's journal, which he maintained almost daily from 1837 (when he was twenty years old) to 1861 (just a year before his death), such a rich and elegant work is his sense of being a traveler, even when not traveling geographically.

Traveling a Good Deal in Moscow

I have traveled a good deal in Concord…. --Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854; 4)

4 For Thoreau, one did not need to travel a substantial physical distance in order to be a traveler, in order to bring a traveler's frame of mind to daily experience. His most famous book, Walden , is well known as an account of the author's ideas and daily experiments in simple living during the two years, two months, and two days (July 4, 1845, to September 6, 1847) he spent inhabiting a simple wooden house that he built on the shore of Walden Pond, a small lake to the west of Boston, Massachusetts. Walden Pond is not a remote location—it is not out in the wilderness. It is on the edge of a small village, much like Moscow, Idaho. The concept of "traveling a good deal in Concord" is a kind of philosophical and psychological riddle. What does it mean to travel extensively in such a small place? The answer to this question is meaningful not only to teachers hoping to design writing classes in the spirit of Thoreau but to all who are interested in travel as an experience and in the literary genre of travel writing.

5 Much of Walden is an exercise in deftly establishing a playful and intellectually challenging system of synonyms, an array of words—"economy," "deliberateness," "simplicity," "dawn," "awakening," "higher laws," etc.—that all add up to powerful probing of what it means to live a mindful and attentive life in the world. "Travel" serves as a key, if subtle, metaphor for the mindful life—it is a metaphor and also, in a sense, a clue: if we can achieve the traveler's perspective without going far afield, then we might accomplish a kind of enlightenment. Thoreau's interest in mindfulness becomes clear in chapter two of Walden , "Where I Lived, and What I Lived For," in which he writes, "Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me. To be awake is to be alive. I have never yet met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?" The latter question implies the author's feeling that he is himself merely evolving as an awakened individual, not yet fully awake, or mindful, in his efforts to live "a poetic or divine life" (90). Thoreau proceeds to assert that "We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn…. I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor" (90). Just what this endeavor might be is not immediately spelled out in the text, but the author does quickly point out the value of focusing on only a few activities or ideas at a time, so as not to let our lives be "frittered away by detail." He writes: "Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand; … and keep your accounts on your thumb nail" (91). The strong emphasis in the crucial second chapter of Walden is on the importance of waking up and living deliberately through a conscious effort to engage in particular activities that support such awakening. It occurs to me that "travel," or simply making one's way through town with the mindset of a traveler, could be one of these activities.

6 It is in the final chapter of the book, titled "Conclusion," that Thoreau makes clear the relationship between travel and living an attentive life. He begins the chapter by cataloguing the various physical locales throughout North America or around the world to which one might travel—Canada, Ohio, Colorado, and even Tierra del Fuego. But Thoreau states: "Our voyaging is only great-circle sailing, and the doctors prescribe for diseases of the skin merely. One hastens to Southern Africa to chase the giraffe; but surely that is not the game he would be after." What comes next is brief quotation from the seventeenth-century English poet William Habbington (but presented anonymously in Thoreau's text), which might be one of the most significant passages in the entire book:

Direct your eye sight inward, and you'll find A thousand regions in your mind Yet undiscovered. Travel them, and be Expert in home-cosmography. (320)

7 This admonition to travel the mysterious territory of one's own mind and master the strange cosmos of the self is actually a challenge to the reader—and probably to the author himself—to focus on self-reflection and small-scale, local movement as if such activities were akin to exploration on a grand, planetary scale. What is really at issue here is not the physical distance of one's journey, but the mental flexibility of one's approach to the world, one's ability to look at the world with a fresh, estranged point of view. Soon after his discussion of the virtues of interior travel, Thoreau explains why he left his simple home at Walden Pond after a few years of experimental living there, writing, "It is remarkable how easily and insensibly we fall into a particular route, and make a beaten track for ourselves" (323). In other words, no matter what we're doing in life, we can fall into a "beaten track" if we're not careful, thus failing to stay "awake."

8 As I thought about my writing class at the University of Idaho, I wondered how I might design a series of readings and writing exercises for university students that would somehow emulate the Thoreauvian objective of achieving ultra-mindfulness in a local environment. One of the greatest challenges in designing such a class is the fact that it took Thoreau himself many years to develop an attentiveness to his environment and his own emotional rhythms and an efficiency of expression that would enable him to describe such travel-without-travel, and I would have only sixteen weeks to achieve this with my own students. The first task, I decided, was to invite my students into the essential philosophical stance of the class, and I did this by asking my students to read the opening chapter of Walden ("Economy") in which he talks about traveling "a good deal" in his small New England village as well as the second chapter and the conclusion, which reveal the author's enthusiasm (some might even say obsession ) for trying to achieve an awakened condition and which, in the end, suggest that waking up to the meaning of one's life in the world might be best accomplished by attempting the paradoxical feat of becoming "expert in home-cosmography." As I stated it among the objectives for my course titled 36 Views of Moscow Mountain: Or, Traveling a Good Deal—with Open Minds and Notebooks—in a Small Place , one of our goals together (along with practicing nonfiction writing skills and learning about the genre of travel writing) would be to "Cultivate a ‘Thoreauvian' way of appreciating the subtleties of the ordinary world."

Windy. Elms Bare.

9 For me, the elegance and heightened sensitivity of Thoreau's engagement with place is most movingly exemplified in his journal, especially in the 1850s after he's mastered the art of observation and nuanced, efficient description of specific natural phenomena and environmental conditions. His early entries in the journal are abstract mini-essays on such topics as truth, beauty, and "The Poet," but over time the journal notations become so immersed in the direct experience of the more-than-human world, in daily sensory experiences, that the pronoun "I" even drops out of many of these records. Lawrence Buell aptly describes this Thoreauvian mode of expression as "self-relinquishment" (156) in his 1995 book The Environmental Imagination , suggesting such writing "question[s] the authority of the superintending consciousness. As such, it opens up the prospect of a thoroughgoing perceptual breakthrough, suggesting the possibility of a more ecocentric state of being than most of us have dreamed of" (144-45). By the time Thoreau wrote "Windy. Elms bare" (372) as his single entry for October 6 and 7, 1853, he had entered what we might call an "ecocentric zone of consciousness" in his work, attaining the ability to channel his complex perceptions of season change (including meteorology and botany and even his own emotional state) into brief, evocative prose.

10 I certainly do not expect my students to be able to do such writing after only a brief introduction to the course and to Thoreau's own methods of journal writing, but after laying the foundation of the Thoreauvian philosophy of nearby travel and explaining to my students what I call the "building blocks of the personal essay" (description, narration, and exposition), I ask them to engage in a preliminary journal-writing exercise that involves preparing five journal entries, each "a paragraph or two in length," that offer detailed physical descriptions of ordinary phenomena from their lives (plants, birds, buildings, street signs, people, food, etc.), emphasizing shape, color, movement or change, shadow, and sometimes sound, smell, taste, and/or touch. The goal of the journal entries, I tell the students, is to begin to get them thinking about close observation, vivid descriptive language, and the potential to give their later essays in the class an effective texture by balancing more abstract information and ideas with evocative descriptive passages and storytelling.

11 I am currently teaching this class, and I am writing this article in early September, as we are entering the fourth week of the semester. The students have just completed the journal-writing exercise and are now preparing to write the first of five brief essays on different aspects of Moscow that will eventually be braided together, as discrete sections of the longer piece, into a full-scale literary essay about Moscow, Idaho, from the perspective of a traveler. For the journal exercise, my students wrote some rather remarkable descriptive statements, which I think bodes well for their upcoming work. One student, Elizabeth Isakson, wrote stunning journal descriptions of a cup of coffee, her own feet, a lemon, a basil leaf, and a patch of grass. For instance, she wrote:

Steaming hot liquid poured into a mug. No cream, just black. Yet it appears the same brown as excretion. The texture tells another story with meniscus that fades from clear to gold and again brown. The smell is intoxicating for those who are addicted. Sweetness fills the nostrils; bitterness rushes over the tongue. The contrast somehow complements itself. Earthy undertones flower up, yet this beverage is much more satisfying than dirt. When the mug runs dry, specks of dark grounds remain swimming in the sunken meniscus. Steam no longer rises because energy has found a new home.

12 For the grassy lawn, she wrote:

Calico with shades of green, the grass is yellowing. Once vibrant, it's now speckled with straw. Sticking out are tall, seeding dandelions. Still some dips in the ground have maintained thick, soft patches of green. The light dances along falling down from the trees above, creating a stained-glass appearance made from various green shades. The individual blades are stiff enough to stand erect, but they will yield to even slight forces of wind or pressure. Made from several long strands seemingly fused together, some blades fray at the end, appearing brittle. But they do not simply break off; they hold fast to the blade to which they belong.

13 The point of this journal writing is for the students to look closely enough at ordinary reality to feel estranged from it, as if they have never before encountered (or attempted to describe) a cup of coffee or a field of grass—or a lemon or a basil leaf or their own body. Thus, the Thoreauvian objective of practicing home-cosmography begins to take shape. The familiar becomes exotic, note-worthy, and strangely beautiful, just as it often does for the geographical travel writer, whose adventures occur far away from where she or he normally lives. Travel, in a sense, is an antidote to complacency, to over-familiarity. But the premise of my class in Thoreauvian travel writing is that a slight shift of perspective can overcome the complacency we might naturally feel in our home surroundings. To accomplish this we need a certain degree of disorientation. This is the next challenge for our class.

The Blessing of Being Lost

14 Most of us take great pains to "get oriented" and "know where we're going," whether this is while running our daily errands or when thinking about the essential trajectories of our lives. We're often instructed by anxious parents to develop a sense of purpose and a sense of direction, if only for the sake of basic safety. But the traveler operates according to a somewhat different set of priorities, perhaps, elevating adventure and insight above basic comfort and security, at least to some degree. This certainly seems to be the case for the Thoreauvian traveler, or for Thoreau himself. In Walden , he writes:

…not until we are completely lost, or turned round,--for a man needs only be turned round once with his eyes shut in this world to be lost,--do we appreciate the vastness and strangeness of Nature. Every man has to learn the points of compass again as often as he awakes, whether from sleep or any abstraction. Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations. (171)

15 I could explicate this passage at length, but that's not really my purpose here. I read this as a celebration of salutary disorientation, of the potential to be lost in such a way as to deepen one's ability to pay attention to oneself and one's surroundings, natural and otherwise. If travel is to a great degree an experience uniquely capable of triggering attentiveness to our own physical and psychological condition, to other cultures and the minds and needs of other people, and to a million small details of our environment that we might take for granted at home but that accrue special significance when we're away, I would argue that much of this attentiveness is owed to the sense of being lost, even the fear of being lost, that often happens when we leave our normal habitat.

16 So in my class I try to help my students "get lost" in a positive way. Here in Moscow, the major local landmark is a place called Moscow Mountain, a forested ridge of land just north of town, running approximately twenty kilometers to the east of the city. Moscow "Mountain" does not really have a single, distinctive peak like a typical mountain—it is, as I say, more of a ridge than a pinnacle. When I began contemplating this class on Thoreauvian travel writing, the central concepts I had in mind were Thoreau's notion of traveling a good deal in Concord and also the idea of looking at a specific place from many different angles. The latter idea is not only Thoreauvian, but perhaps well captured in the eighteen-century Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai's series of woodblock prints known as 36 Views of Mt. Fuji , which offers an array of different angles on the mountain itself and on other landscape features (lakes, the sea, forests, clouds, trees, wind) and human behavior which is represented in many of the prints, often with Mt. Fuji in the distant background or off to the side. In fact, I imagine Hokusai's approach to representing Mt. Fuji as so important to the concept of this travel writing class that I call the class "36 Views of Moscow Mountain," symbolizing the multiple approaches I'll be asking my students to take in contemplating and describing not only Moscow Mountain itself, but the culture and landscape and the essential experience of Moscow the town. The idea of using Hokusai's series of prints as a focal point of this class came to me, in part, from reading American studies scholar Cathy Davidson's 36 Views of Mount Fuji: On Finding Myself in Japan , a memoir that offers sixteen short essays about different facets of her life as a visiting professor in that island nation.

17 The first of five brief essays my students will prepare for the class is what I'm calling a "Moscow Mountain descriptive essay," building upon the small descriptive journal entries they've written recently. In this case, though, I am asking the students to describe the shapes and colors of the Moscow Mountain ridge, while also telling a brief story or two about their observations of the mountain, either by visiting the mountain itself to take a walk or a bike ride or by explaining how they glimpse portions of the darkly forested ridge in the distance while walking around the University of Idaho campus or doing things in town. In preparation for the Moscow Mountain essays, we read several essays or book chapters that emphasize "organizing principles" in writing, often the use of particular landscape features, such as trees or mountains, as a literary focal point. For instance, in David Gessner's "Soaring with Castro," from his 2007 book Soaring with Fidel: An Osprey Odyssey from Cape Cod to Cuba and Beyond , he not only refers to La Gran Piedra (a small mountain in southeastern Cuba) as a narrative focal point, but to the osprey, or fish eagle, itself and its migratory journey as an organizing principle for his literary project (203). Likewise, in his essay "I Climb a Tree and Become Dissatisfied with My Lot," Chicago author Leonard Dubkin writes about his decision, as a newly fired journalist, to climb up a tree in Chicago's Lincoln Park to observe and listen to the birds that gather in the green branches in the evening, despite the fact that most adults would consider this a strange and inappropriate activity. We also looked at several of Hokusai's woodblock prints and analyzed these together in class, trying to determine how the mountain served as an organizing principle for each print or whether there were other key features of the prints—clouds, ocean waves, hats and pieces of paper floating in the wind, humans bent over in labor—that dominate the images, with Fuji looking on in the distance.

18 I asked my students to think of Hokusai's representations of Mt. Fuji as aesthetic models, or metaphors, for what they might try to do in their brief (2-3 pages) literary essays about Moscow Mountain. What I soon discovered was that many of my students, even students who have spent their entire lives in Moscow, either were not aware of Moscow Mountain at all or had never actually set foot on the mountain. So we spent half an hour during one class session, walking to a vantage point on the university campus, where I could point out where the mountain is and we could discuss how one might begin to write about such a landscape feature in a literary essay. Although I had thought of the essay describing the mountain as a way of encouraging the students to think about a familiar landscape as an orienting device, I quickly learned that this will be a rather challenging exercise for many of the students, as it will force them to think about an object or a place that is easily visible during their ordinary lives, but that they typically ignore. Paying attention to the mountain, the ridge, will compel them to reorient themselves in this city and think about a background landscape feature that they've been taking for granted until now. I think of this as an act of disorientation or being lost—a process of rethinking their own presence in this town that has a nearby mountain that most of them seldom think about. I believe Thoreau would consider this a good, healthy experience, a way of being present anew in a familiar place.

36 Views—Or, When You Invert Your Head

19 Another key aspect of Hokusai's visual project and Thoreau's literary project is the idea of changing perspective. One can view Mt. Fuji from 36 different points of views, or from thousands of different perspectives, and it is never quite the same place—every perspective is original, fresh, mind-expanding. The impulse to shift perspective in pursuit of mindfulness is also ever-present in Thoreau's work, particularly in his personal journal and in Walden . This idea is particularly evident, to me, in the chapter of Walden titled "The Ponds," where he writes:

Standing on the smooth sandy beach at the east end of the pond, in a calm September afternoon, when a slight haze makes the opposite shore line indistinct, I have seen whence came the expression, "the glassy surface of a lake." When you invert your head, it looks like a thread of finest gossamer stretched across the valley, and gleaming against the distinct pine woods, separating one stratum of the atmosphere from another. (186)

20 Elsewhere in the chapter, Thoreau describes the view of the pond from the top of nearby hills and the shapes and colors of pebbles in the water when viewed from close up. He chances physical perspective again and again throughout the chapter, but it is in the act of looking upside down, actually suggesting that one might invert one's head, that he most vividly conveys the idea of looking at the world in different ways in order to be lost and awakened, just as the traveler to a distant land might feel lost and invigorated by such exposure to an unknown place.

21 After asking students to write their first essay about Moscow Mountain, I give them four additional short essays to write, each two to four pages long. We read short examples of place-based essays, some of them explicitly related to travel, and then the students work on their own essays on similar topics. The second short essay is about food—I call this the "Moscow Meal" essay. We read the final chapter of Michael Pollan's The Omnivore's Dilemma (2006), "The Perfect Meal," and Anthony Bourdain's chapter "Where Cooks Come From" in the book A Cook's Tour (2001) are two of the works we study in preparation for the food essay. The three remaining short essays including a "Moscow People" essay (exploring local characters are important facets of the place), a more philosophical essay about "the concept of Moscow," and a final "Moscow Encounter" essay that tells the story of a dramatic moment of interaction with a person, an animal, a memorable thing to eat or drink, a sunset, or something else. Along the way, we read the work of Wendell Berry, Joan Didion, Barbara Kingsolver, Kim Stafford, Paul Theroux, and other authors. Before each small essay is due, we spend a class session holding small-group workshops, allowing the students to discuss their essays-in-progress with each other and share portions of their manuscripts. The idea is that they will learn about writing even by talking with each other about their essays. In addition to writing about Moscow from various angles, they will learn about additional points of view by considering the angles of insight developed by their fellow students. All of this is the writerly equivalent of "inverting [their] heads."

Beneath the Smooth Skin of Place

22 Aside from Thoreau's writing and Hokusai's images, perhaps the most important writer to provide inspiration for this class is Indiana-based essayist Scott Russell Sanders. Shortly after introducing the students to Thoreau's key ideas in Walden and to the richness of his descriptive writing in the journal, I ask them to read his essay "Buckeye," which first appeared in Sanders's Writing from the Center (1995). "Buckeye" demonstrates the elegant braiding together of descriptive, narrative, and expository/reflective prose, and it also offers a strong argument about the importance of creating literature and art about place—what he refers to as "shared lore" (5)—as a way of articulating the meaning of a place and potentially saving places that would otherwise be exploited for resources, flooded behind dams, or otherwise neglected or damaged. The essay uses many of the essential literary devices, ranging from dialogue to narrative scenes, that I hope my students will practice in their own essays, while also offering a vivid argument in support of the kind of place-based writing the students are working on.

23 Another vital aspect of our work together in this class is the effort to capture the wonderful idiosyncrasies of this place, akin to the idiosyncrasies of any place that we examine closely enough to reveal its unique personality. Sanders's essay "Beneath the Smooth Skin of America," which we study together in Week 9 of the course, addresses this topic poignantly. The author challenges readers to learn the "durable realities" of the places where they live, the details of "watershed, biome, habitat, food-chain, climate, topography, ecosystem and the areas defined by these natural features they call bioregions" (17). "The earth," he writes, "needs fewer tourists and more inhabitants" (16). By Week 9 of the semester, the students have written about Moscow Mountain, about local food, and about local characters, and they are ready at this point to reflect on some of the more philosophical dimensions of living in a small academic village surrounded by farmland and beyond that surrounded by the Cascade mountain range to the West and the Rockies to the East. "We need a richer vocabulary of place" (18), urges Sanders. By this point in the semester, by reading various examples of place-based writing and by practicing their own powers of observation and expression, my students will, I hope, have developed a somewhat richer vocabulary to describe their own experiences in this specific place, a place they've been trying to explore with "open minds and notebooks." Sanders argues that

if we pay attention, we begin to notice patterns in the local landscape. Perceiving those patterns, acquiring names and theories and stories for them, we cease to be tourists and become inhabitants. The bioregional consciousness I am talking about means bearing your place in mind, keeping track of its condition and needs, committing yourself to its care. (18)

24 Many of my students will spend only four or five years in Moscow, long enough to earn a degree before moving back to their hometowns or journeying out into the world in pursuit of jobs or further education. Moscow will be a waystation for some of these student writers, not a permanent home. Yet I am hoping that this semester-long experiment in Thoreauvian attentiveness and place-based writing will infect these young people with both the bioregional consciousness Sanders describes and a broader fascination with place, including the cultural (yes, the human ) dimensions of this and any other place. I feel such a mindfulness will enrich the lives of my students, whether they remain here or move to any other location on the planet or many such locations in succession.

25 Toward the end of "Beneath the Smooth Skin of America," Sanders tells the story of encountering a father with two young daughters near a city park in Bloomington, Indiana, where he lives. Sanders is "grazing" on wild mulberries from a neighborhood tree, and the girls are keen to join him in savoring the local fruit. But their father pulls them away, stating, "Thank you very much, but we never eat anything that grows wild. Never ever." To this Sanders responds: "If you hold by that rule, you will not get sick from eating poison berries, but neither will you be nourished from eating sweet ones. Why not learn to distinguish one from the other? Why feed belly and mind only from packages?" (19-20). By looking at Moscow Mountain—and at Moscow, Idaho, more broadly—from numerous points of view, my students, I hope, will nourish their own bellies and minds with the wild fruit and ideas of this place. I say this while chewing a tart, juicy, and, yes, slightly sweet plum that I pulled from a feral tree in my own Moscow neighborhood yesterday, an emblem of engagement, of being here.

Bibliography

BUELL, Lawrence, The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture , Harvard University Press, 1995.

DAVIDSON, Cathy, 36 Views of Mount Fuji: On Finding Myself in Japan , Duke University Press, 2006.

DUBKIN, Leonard, "I Climb a Tree and Become Dissatisfied with My Lot." Enchanted Streets: The Unlikely Adventures of an Urban Nature Lover , Little, Brown and Company, 1947, 34-42.

GESSNER, David, Soaring with Fidel: An Osprey Odyssey from Cape Cod to Cuba and Beyond , Beacon, 2007.

ISAKSON, Elizabeth, "Journals." Assignment for 36 Views of Moscow Mountain (English 208), University of Idaho, Fall 2018.

SANDERS, Scott Russell, "Buckeye" and "Beneath the Smooth Skin of America." Writing from the Center , Indiana University Press, 1995, pp. 1-8, 9-21.

SLOVIC, Scott, "Teaching with Wolves", Western American Literature 52.3 (Fall 2017): 323-31.

THOREAU, Henry David, "October 1-20, 1853", Being in the World: An Environmental Reader for Writers , edited by Scott H. Slovic and Terrell F. Dixon, Macmillan, 1993, 371-75.

THOREAU, Henry David, Walden . 1854. Princeton University Press, 1971.

Bibliographical reference

Scott Slovic , “ 36 Views of Moscow Mountain: Teaching Travel Writing and Mindfulness in the Tradition of Hokusai and Thoreau ” , Caliban , 59 | 2018, 41-54.

Electronic reference

Scott Slovic , “ 36 Views of Moscow Mountain: Teaching Travel Writing and Mindfulness in the Tradition of Hokusai and Thoreau ” , Caliban [Online], 59 | 2018, Online since 01 June 2018 , connection on 04 April 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/caliban/3688; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/caliban.3688

About the author

Scott slovic.

University of Idaho Scott Slovic is University Distinguished Professor of Environmental Humanities at the University of Idaho, USA. The author and editor of many books and articles, he edited the journal ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment from 1995 to 2020. His latest coedited book is The Routledge Handbook of Ecocriticism and Environmental Communication (2019).

By this author

- Introduction (version en français) [Full text] Introduction [Full text | translation | en] Published in Caliban , 64 | 2020

- To Collapse or Not to Collapse? A Joint Interview [Full text] Published in Caliban , 63 | 2020

- Furrowed Brows, Questioning Earth: Minding the Loess Soil of the Palouse [Full text] Published in Caliban , 61 | 2019

- Foreword: Thinking of “Earth Island” on Earth Day 2016 [Full text] Published in Caliban , 55 | 2016

The text only may be used under licence CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 . All other elements (illustrations, imported files) are “All rights reserved”, unless otherwise stated.

Full text issues

- 67-68 | 2022 Religious Dispute and Toleration in Early Modern Literature and History

- 65-66 | 2021 Peterloo 1819 and After: Perspectives from Britain and Beyond

- 64 | 2020 Animal Love. Considering Animal Attachments in Anglophone Literature and Culture

- 63 | 2020 Dynamics of Collapse in Fantasy, the Fantastic and SF

- 62 | 2019 Female Suffrage in British Art, Literature and History

- 61 | 2019 Land’s Furrows and Sorrows in Anglophone Countries

- 60 | 2018 The Life of Forgetting in Twentieth- and Twenty-First-Century British Literature

- 59 | 2018 Anglophone Travel and Exploration Writing: Meetings Between the Human and Nonhuman

- 58 | 2017 The Mediterranean and its Hinterlands

- 57 | 2017 The Animal Question in Alice Munro's Stories

- 56 | 2016 Disappearances - American literature and arts

- 55 | 2016 Sharing the Planet

- 54 | 2015 Forms of Diplomacy (16 th -21 st century)

- 53 | 2015 Representing World War One: Art’s Response to War

- 52 | 2014 Caliban and his transmutations

Anglophonia/Caliban

- Issues list

Presentation

- Document sans titre

- Editorial Policy

- Instructions for authors

- Ventes et abonnement

Informations

- Mentions légales et Crédits

- Publishing policies

Newsletters

- OpenEdition Newsletter

In collaboration with

Electronic ISSN 2431-1766

Read detailed presentation

Site map – Syndication

Privacy Policy – About Cookies – Report a problem

OpenEdition Journals member – Published with Lodel – Administration only

You will be redirected to OpenEdition Search

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Program in Creative Writing offers Princeton undergraduates the opportunity to craft original work under the guidance of some of today's most respected practicing writers including Michael Dickman, Katie Farris, Aleksandar Hemon, A.M. Homes, Ilya Kaminsky, Christina Lazaridi, Yiyun Li, Paul Muldoon, Patricia Smith and Susan Wheeler.. Small workshop courses, averaging eight to ten ...

This is a workshop in the fundamentals of writing plays. Through writing prompts, exercises, study and reflection, students will be guided in the creation of original dramatic material. Attention will be given to character, structure, dramatic action, monologue, dialogue, language. JRN 240 / CWR 240.

The Program in Creative Writing, part of the Lewis Center for the Arts, with a minor in creative writing, like our present certificate students, will encounter a rigorous framework of courses. These courses are designed, first and foremost, to teach the students how to read like a writer, thoughtfully, artistically, curiously, with an open mind attuned to the nuances of any human situation.

Princeton University's Lewis Center for the Arts has named award-winning writer Yiyun Li as the new director of the University's Program in Creative Writing. Li, a Professor of Creative Writing on the Princeton faculty since 2017, succeeds Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri, who has led the program since 2019. Li begins her tenure as director on July 1.

We will make available—to all faculty—regular anti-racist trainings by an outside thinker about creative writing and anti-racist practices. We are in the process of compiling inclusive workshop practices that can be adapted for any CWR course and will convene faculty brown-bag lunch meetings specifically to share BIPOC-centered practices ...

April 2, 2024. The Writing Center is open for in-person appointments! We look forward to meeting with you on the 2nd floor of New South. Learn more about Writing Center appointments and our scheduling system. Every writer needs a reader, and the Writing Center has a reader for every writer! Trained to respond to writing from a variety of genres ...

The Lewis Center for the Arts is an academic unit made up of programs in creative writing, dance, theater, music theater and visual arts, as well as the Princeton Atelier.Lewis Center courses are offered with the conviction that art making is an essential tool for examining our histories and our most pressing social challenges, envisioning creative responses, and making sense of our lives in ...

April 2, 2020. One of my favorite classes at Princeton is "CWR201: Creative Writing - Poetry," a class I'm taking with Professor Jenny Xie. As a computer science engineering student, I'm often deluged with problem sets and programming projects. However, I've always been a writer at heart. In high school, I was heavily involved in ...

Princeton's creative writing program — which has produced such noted contemporary writers as novelists Jonathan Safran Foer '99 and Jodi Picoult '87 — is "unparalleled," said Lee, the program's director. University creative writing programs, he said, usually are created to offer master's degrees in fine arts. ...

Degree Information. A Master of Arts degree in Creative Writing takes from one to two years, and requires a thesis and often a comprehensive exam in English Literature. A Master of Fine Arts usually takes two to four years (though students can sometimes apply credits from an M.A.) and usually requires a manuscript of publishable quality.

Poetry - Taboo: Wishbone Trilogy Part One (2004); Scandalize My Name (2002); Pleasure Dome: New and Collected Poems, 1975-1999 (2001); Talking Dirty to the Gods (2000), finalist, National Book Critics Circle Award; Thieves of Paradise (1999), finalist, National Book Critics Circle Award; The ...

Conceived by the Student Ambassadors of Princeton University Concerts, this writing contest gave students a free ticket to attend a Princeton University Concert in the legendary Alexander Hall, in return for a creative written response to the performance—and a chance to win a cash prize. ... including professors in the Creative Writing ...

Workshops ranging from cryo painting tote bags to origami engineering foster a culture of collaboration and innovation, inspiring students to push the boundaries of their creativity. Finally, Princeton's makerspace offers students the chance to delve into a multitude of crafts and technologies. From designing custom stickers to crafting ...

The University's annual public celebration of research and creativity, Princeton Research Day, will be held May 9 at Frist Campus Center. Free and open to the public, the event offers a glimpse into the research and creative work conducted by early career researchers from across the University. For presenters, it's a chance to practice explainin...

BUELL, Lawrence, The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture, Harvard University Press, 1995. DAVIDSON, Cathy, 36 Views of Mount Fuji: On Finding Myself in Japan, Duke University Press, 2006. DUBKIN, Leonard, "I Climb a Tree and Become Dissatisfied with My Lot." Enchanted Streets: The Unlikely Adventures of an Urban Nature Lover, Little, Brown ...

Undergraduate Courses. East European Literature. SLA 345 / ECS 354 / RES 345. Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace: Writing as Fighting. SLA 415 / COM 415 / RES 415 / ECS 417. The Soviet Empire. HIS 362 / RES 362. Revolutionary Russia. Rebellion, Opposition, and Dissent, 1860s-2020s.

Vladimir Ivanovich Guerrier (Russian: Владимир Иванович Герье; 29 May [O.S. 17 May] 1837 - 30 June 1919) was a Russian historian, professor of history at Moscow State University from 1868 to 1904. As the founder of the "Courses Guerrier", he was a leading instigator of higher education for women in Russia.He was also a member of the Moscow City Duma, the State Council of ...

Experience in: political research, discourse analysis, academic and creative writing, simultaneous translation, in-depth interview, documentary filmmaking. Organization of scientific conferences, project management. Fluent Russian and English, basic French, Spanish | Learn more about Anna-Liza Starkova's work experience, education, connections & more by visiting their profile on LinkedIn