How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 5 min read

Using the Scientific Method to Solve Problems

How the scientific method and reasoning can help simplify processes and solve problems.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

The processes of problem-solving and decision-making can be complicated and drawn out. In this article we look at how the scientific method, along with deductive and inductive reasoning can help simplify these processes.

‘It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has information. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit our theories, instead of theories to suit facts.’ Sherlock Holmes

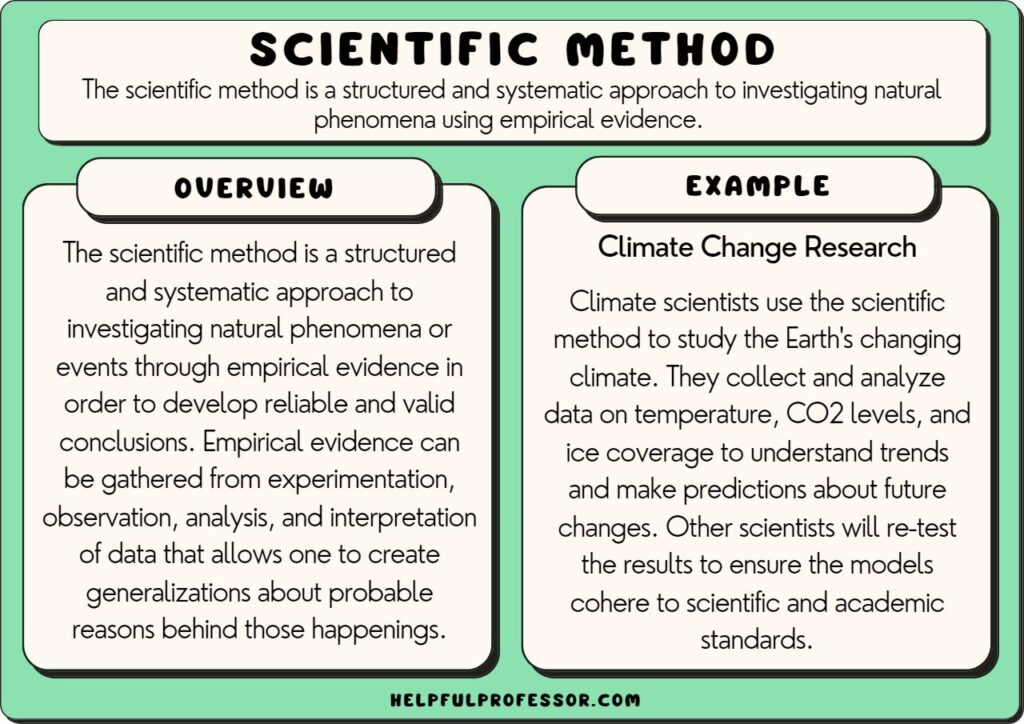

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a process used to explore observations and answer questions. Originally used by scientists looking to prove new theories, its use has spread into many other areas, including that of problem-solving and decision-making.

The scientific method is designed to eliminate the influences of bias, prejudice and personal beliefs when testing a hypothesis or theory. It has developed alongside science itself, with origins going back to the 13th century. The scientific method is generally described as a series of steps.

- observations/theory

- explanation/conclusion

The first step is to develop a theory about the particular area of interest. A theory, in the context of logic or problem-solving, is a conjecture or speculation about something that is not necessarily fact, often based on a series of observations.

Once a theory has been devised, it can be questioned and refined into more specific hypotheses that can be tested. The hypotheses are potential explanations for the theory.

The testing, and subsequent analysis, of these hypotheses will eventually lead to a conclus ion which can prove or disprove the original theory.

Applying the Scientific Method to Problem-Solving

How can the scientific method be used to solve a problem, such as the color printer is not working?

1. Use observations to develop a theory.

In order to solve the problem, it must first be clear what the problem is. Observations made about the problem should be used to develop a theory. In this particular problem the theory might be that the color printer has run out of ink. This theory is developed as the result of observing the increasingly faded output from the printer.

2. Form a hypothesis.

Note down all the possible reasons for the problem. In this situation they might include:

- The printer is set up as the default printer for all 40 people in the department and so is used more frequently than necessary.

- There has been increased usage of the printer due to non-work related printing.

- In an attempt to reduce costs, poor quality ink cartridges with limited amounts of ink in them have been purchased.

- The printer is faulty.

All these possible reasons are hypotheses.

3. Test the hypothesis.

Once as many hypotheses (or reasons) as possible have been thought of, then each one can be tested to discern if it is the cause of the problem. An appropriate test needs to be devised for each hypothesis. For example, it is fairly quick to ask everyone to check the default settings of the printer on each PC, or to check if the cartridge supplier has changed.

4. Analyze the test results.

Once all the hypotheses have been tested, the results can be analyzed. The type and depth of analysis will be dependant on each individual problem, and the tests appropriate to it. In many cases the analysis will be a very quick thought process. In others, where considerable information has been collated, a more structured approach, such as the use of graphs, tables or spreadsheets, may be required.

5. Draw a conclusion.

Based on the results of the tests, a conclusion can then be drawn about exactly what is causing the problem. The appropriate remedial action can then be taken, such as asking everyone to amend their default print settings, or changing the cartridge supplier.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

The scientific method involves the use of two basic types of reasoning, inductive and deductive.

Inductive reasoning makes a conclusion based on a set of empirical results. Empirical results are the product of the collection of evidence from observations. For example:

‘Every time it rains the pavement gets wet, therefore rain must be water’.

There has been no scientific determination in the hypothesis that rain is water, it is purely based on observation. The formation of a hypothesis in this manner is sometimes referred to as an educated guess. An educated guess, whilst not based on hard facts, must still be plausible, and consistent with what we already know, in order to present a reasonable argument.

Deductive reasoning can be thought of most simply in terms of ‘If A and B, then C’. For example:

- if the window is above the desk, and

- the desk is above the floor, then

- the window must be above the floor

It works by building on a series of conclusions, which results in one final answer.

Social Sciences and the Scientific Method

The scientific method can be used to address any situation or problem where a theory can be developed. Although more often associated with natural sciences, it can also be used to develop theories in social sciences (such as psychology, sociology and linguistics), using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

Quantitative information is information that can be measured, and tends to focus on numbers and frequencies. Typically quantitative information might be gathered by experiments, questionnaires or psychometric tests. Qualitative information, on the other hand, is based on information describing meaning, such as human behavior, and the reasons behind it. Qualitative information is gathered by way of interviews and case studies, which are possibly not as statistically accurate as quantitative methods, but provide a more in-depth and rich description.

The resultant information can then be used to prove, or disprove, a hypothesis. Using a mix of quantitative and qualitative information is more likely to produce a rounded result based on the factual, quantitative information enriched and backed up by actual experience and qualitative information.

In terms of problem-solving or decision-making, for example, the qualitative information is that gained by looking at the ‘how’ and ‘why’ , whereas quantitative information would come from the ‘where’, ‘what’ and ‘when’.

It may seem easy to come up with a brilliant idea, or to suspect what the cause of a problem may be. However things can get more complicated when the idea needs to be evaluated, or when there may be more than one potential cause of a problem. In these situations, the use of the scientific method, and its associated reasoning, can help the user come to a decision, or reach a solution, secure in the knowledge that all options have been considered.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Pain Points Podcast - Balancing Work And Kids

Pain Points Podcast - Improving Culture

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Pain points podcast - what is ai.

Exploring Artificial Intelligence

Pain Points Podcast - How Do I Get Organized?

It's Time to Get Yourself Sorted!

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Handy's motivation theory.

Motivating People to Work Hard

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

The Scientific Method Tutorial

The scientific method, steps in the scientific method.

There is a great deal of variation in the specific techniques scientists use explore the natural world. However, the following steps characterize the majority of scientific investigations:

Step 1: Make observations Step 2: Propose a hypothesis to explain observations Step 3: Test the hypothesis with further observations or experiments Step 4: Analyze data Step 5: State conclusions about hypothesis based on data analysis

Each of these steps is explained briefly below, and in more detail later in this section.

Step 1: Make observations

A scientific inquiry typically starts with observations. Often, simple observations will trigger a question in the researcher's mind.

Example: A biologist frequently sees monarch caterpillars feeding on milkweed plants, but rarely sees them feeding on other types of plants. She wonders if it is because the caterpillars prefer milkweed over other food choices.

Step 2: Propose a hypothesis

The researcher develops a hypothesis (singular) or hypotheses (plural) to explain these observations. A hypothesis is a tentative explanation of a phenomenon or observation(s) that can be supported or falsified by further observations or experimentation.

Example: The researcher hypothesizes that monarch caterpillars prefer to feed on milkweed compared to other common plants. (Notice how the hypothesis is a statement, not a question as in step 1.)

Step 3: Test the hypothesis

The researcher makes further observations and/or may design an experiment to test the hypothesis. An experiment is a controlled situation created by a researcher to test the validity of a hypothesis. Whether further observations or an experiment is used to test the hypothesis will depend on the nature of the question and the practicality of manipulating the factors involved.

Example: The researcher sets up an experiment in the lab in which a number of monarch caterpillars are given a choice between milkweed and a number of other common plants to feed on.

Step 4: Analyze data

The researcher summarizes and analyzes the information, or data, generated by these further observations or experiments.

Example: In her experiment, milkweed was chosen by caterpillars 9 times out of 10 over all other plant selections.

Step 5: State conclusions

The researcher interprets the results of experiments or observations and forms conclusions about the meaning of these results. These conclusions are generally expressed as probability statements about their hypothesis.

Example: She concludes that when given a choice, 90 percent of monarch caterpillars prefer to feed on milkweed over other common plants.

Often, the results of one scientific study will raise questions that may be addressed in subsequent research. For example, the above study might lead the researcher to wonder why monarchs seem to prefer to feed on milkweed, and she may plan additional experiments to explore this question. For example, perhaps the milkweed has higher nutritional value than other available plants.

Return to top of page

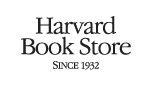

The Scientific Method Flowchart

The steps in the scientific method are presented visually in the following flow chart. The question raised or the results obtained at each step directly determine how the next step will proceed. Following the flow of the arrows, pass the cursor over each blue box. An explanation and example of each step will appear. As you read the example given at each step, see if you can predict what the next step will be.

Activity: Apply the Scientific Method to Everyday Life Use the steps of the scientific method described above to solve a problem in real life. Suppose you come home one evening and flick the light switch only to find that the light doesn’t turn on. What is your hypothesis? How will you test that hypothesis? Based on the result of this test, what are your conclusions? Follow your instructor's directions for submitting your response.

The above flowchart illustrates the logical sequence of conclusions and decisions in a typical scientific study. There are some important points to note about this process:

1. The steps are clearly linked.

The steps in this process are clearly linked. The hypothesis, formed as a potential explanation for the initial observations, becomes the focus of the study. The hypothesis will determine what further observations are needed or what type of experiment should be done to test its validity. The conclusions of the experiment or further observations will either be in agreement with or will contradict the hypothesis. If the results are in agreement with the hypothesis, this does not prove that the hypothesis is true! In scientific terms, it "lends support" to the hypothesis, which will be tested again and again under a variety of circumstances before researchers accept it as a fairly reliable description of reality.

2. The same steps are not followed in all types of research.

The steps described above present a generalized method followed in a many scientific investigations. These steps are not carved in stone. The question the researcher wishes to answer will influence the steps in the method and how they will be carried out. For example, astronomers do not perform many experiments as defined here. They tend to rely on observations to test theories. Biologists and chemists have the ability to change conditions in a test tube and then observe whether the outcome supports or invalidates their starting hypothesis, while astronomers are not able to change the path of Jupiter around the Sun and observe the outcome!

3. Collected observations may lead to the development of theories.

When a large number of observations and/or experimental results have been compiled, and all are consistent with a generalized description of how some element of nature operates, this description is called a theory. Theories are much broader than hypotheses and are supported by a wide range of evidence. Theories are important scientific tools. They provide a context for interpretation of new observations and also suggest experiments to test their own validity. Theories are discussed in more detail in another section.

The Scientific Method in Detail

In the sections that follow, each step in the scientific method is described in more detail.

Step 1: Observations

Observations in science.

An observation is some thing, event, or phenomenon that is noticed or observed. Observations are listed as the first step in the scientific method because they often provide a starting point, a source of questions a researcher may ask. For example, the observation that leaves change color in the fall may lead a researcher to ask why this is so, and to propose a hypothesis to explain this phenomena. In fact, observations also will provide the key to answering the research question.

In science, observations form the foundation of all hypotheses, experiments, and theories. In an experiment, the researcher carefully plans what observations will be made and how they will be recorded. To be accepted, scientific conclusions and theories must be supported by all available observations. If new observations are made which seem to contradict an established theory, that theory will be re-examined and may be revised to explain the new facts. Observations are the nuts and bolts of science that researchers use to piece together a better understanding of nature.

Observations in science are made in a way that can be precisely communicated to (and verified by) other researchers. In many types of studies (especially in chemistry, physics, and biology), quantitative observations are used. A quantitative observation is one that is expressed and recorded as a quantity, using some standard system of measurement. Quantities such as size, volume, weight, time, distance, or a host of others may be measured in scientific studies.

Some observations that researchers need to make may be difficult or impossible to quantify. Take the example of color. Not all individuals perceive color in exactly the same way. Even apart from limiting conditions such as colorblindness, the way two people see and describe the color of a particular flower, for example, will not be the same. Color, as perceived by the human eye, is an example of a qualitative observation.

Qualitative observations note qualities associated with subjects or samples that are not readily measured. Other examples of qualitative observations might be descriptions of mating behaviors, human facial expressions, or "yes/no" type of data, where some factor is present or absent. Though the qualities of an object may be more difficult to describe or measure than any quantities associated with it, every attempt is made to minimize the effects of the subjective perceptions of the researcher in the process. Some types of studies, such as those in the social and behavioral sciences (which deal with highly variable human subjects), may rely heavily on qualitative observations.

Question: Why are observations important to science?

Limits of Observations

Because all observations rely to some degree on the senses (eyes, ears, or steady hand) of the researcher, complete objectivity is impossible. Our human perceptions are limited by the physical abilities of our sense organs and are interpreted according to our understanding of how the world works, which can be influenced by culture, experience, or education. According to science education specialist, George F. Kneller, "Surprising as it may seem, there is no fact that is not colored by our preconceptions" ("A Method of Enquiry," from Science and Its Ways of Knowing [Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1997], 15).

Observations made by a scientist are also limited by the sensitivity of whatever equipment he is using. Research findings will be limited at times by the available technology. For example, Italian physicist and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was reportedly the first person to observe the heavens with a telescope. Imagine how it must have felt to him to see the heavens through this amazing new instrument! It opened a window to the stars and planets and allowed new observations undreamed of before.

In the centuries since Galileo, increasingly more powerful telescopes have been devised that dwarf the power of that first device. In the past decade, we have marveled at images from deep space , courtesy of the Hubble Space Telescope, a large telescope that orbits Earth. Because of its view from outside the distorting effects of the atmosphere, the Hubble can look 50 times farther into space than the best earth-bound telescopes, and resolve details a tenth of the size (Seeds, Michael A., Horizons: Exploring the Universe , 5 th ed. [Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1998], 86-87).

Construction is underway on a new radio telescope that scientists say will be able to detect electromagnetic waves from the very edges of the universe! This joint U.S.-Mexican project may allow us to ask questions about the origins of the universe and the beginnings of time that we could never have hoped to answer before. Completion of the new telescope is expected by the end of 2001.

Although the amount of detail observed by Galileo and today's astronomers is vastly different, the stars and their relationships have not changed very much. Yet with each technological advance, the level of detail of observation has been increased, and with it, the power to answer more and more challenging questions with greater precision.

Question: What are some of the differences between a casual observation and a 'scientific observation'?

Step 2: The Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a statement created by the researcher as a potential explanation for an observation or phenomena. The hypothesis converts the researcher's original question into a statement that can be used to make predictions about what should be observed if the hypothesis is true. For example, given the hypothesis, "exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation increases the risk of skin cancer," one would predict higher rates of skin cancer among people with greater UV exposure. These predictions could be tested by comparing skin cancer rates among individuals with varying amounts of UV exposure. Note how the hypothesis itself determines what experiments or further observations should be made to test its validity. Results of tests are then compared to predictions from the hypothesis, and conclusions are stated in terms of whether or not the data supports the hypothesis. So the hypothesis serves a guide to the full process of scientific inquiry.

The Qualities of a Good Hypothesis

- A hypothesis must be testable or provide predictions that are testable. It can potentially be shown to be false by further observations or experimentation.

- A hypothesis should be specific. If it is too general it cannot be tested, or tests will have so many variables that the results will be complicated and difficult to interpret. A well-written hypothesis is so specific it actually determines how the experiment should be set up.

- A hypothesis should not include any untested assumptions if they can be avoided. The hypothesis itself may be an assumption that is being tested, but it should be phrased in a way that does not include assumptions that are not tested in the experiment.

- It is okay (and sometimes a good idea) to develop more than one hypothesis to explain a set of observations. Competing hypotheses can often be tested side-by-side in the same experiment.

Question: Why is the hypothesis important to the scientific method?

Step 3: Testing the Hypothesis

A hypothesis may be tested in one of two ways: by making additional observations of a natural situation, or by setting up an experiment. In either case, the hypothesis is used to make predictions, and the observations or experimental data collected are examined to determine if they are consistent or inconsistent with those predictions. Hypothesis testing, especially through experimentation, is at the core of the scientific process. It is how scientists gain a better understanding of how things work.

Testing a Hypothesis by Observation

Some hypotheses may be tested through simple observation. For example, a researcher may formulate the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east. What might an alternative hypothesis be? If his hypothesis is correct, he would predict that the sun will rise in the east tomorrow. He can easily test such a prediction by rising before dawn and going out to observe the sunrise. If the sun rises in the west, he will have disproved the hypothesis. He will have shown that it does not hold true in every situation. However, if he observes on that morning that the sun does in fact rise in the east, he has not proven the hypothesis. He has made a single observation that is consistent with, or supports, the hypothesis. As a scientist, to confidently state that the sun will always rise in the east, he will want to make many observations, under a variety of circumstances. Note that in this instance no manipulation of circumstance is required to test the hypothesis (i.e., you aren't altering the sun in any way).

Testing a Hypothesis by Experimentation

An experiment is a controlled series of observations designed to test a specific hypothesis. In an experiment, the researcher manipulates factors related to the hypothesis in such a way that the effect of these factors on the observations (data) can be readily measured and compared. Most experiments are an attempt to define a cause-and-effect relationship between two factors or events—to explain why something happens. For example, with the hypothesis "roses planted in sunny areas bloom earlier than those grown in shady areas," the experiment would be testing a cause-and-effect relationship between sunlight and time of blooming.

A major advantage of setting up an experiment versus making observations of what is already available is that it allows the researcher to control all the factors or events related to the hypothesis, so that the true cause of an event can be more easily isolated. In all cases, the hypothesis itself will determine the way the experiment will be set up. For example, suppose my hypothesis is "the weight of an object is proportional to the amount of time it takes to fall a certain distance." How would you test this hypothesis?

The Qualities of a Good Experiment

- The experiment must be conducted on a group of subjects that are narrowly defined and have certain aspects in common. This is the group to which any conclusions must later be confined. (Examples of possible subjects: female cancer patients over age 40, E. coli bacteria, red giant stars, the nicotine molecule and its derivatives.)

- All subjects of the experiment should be (ideally) completely alike in all ways except for the factor or factors that are being tested. Factors that are compared in scientific experiments are called variables. A variable is some aspect of a subject or event that may differ over time or from one group of subjects to another. For example, if a biologist wanted to test the effect of nitrogen on grass growth, he would apply different amounts of nitrogen fertilizer to several plots of grass. The grass in each of the plots should be as alike as possible so that any difference in growth could be attributed to the effect of the nitrogen. For example, all the grass should be of the same species, planted at the same time and at the same density, receive the same amount of water and sunlight, and so on. The variable in this case would be the amount of nitrogen applied to the plants. The researcher would not compare differing amounts of nitrogen across different grass species to determine the effect of nitrogen on grass growth. What is the problem with using different species of plants to compare the effect of nitrogen on plant growth? There are different kinds of variables in an experiment. A factor that the experimenter controls, and changes intentionally to determine if it has an effect, is called an independent variable . A factor that is recorded as data in the experiment, and which is compared across different groups of subjects, is called a dependent variable . In many cases, the value of the dependent variable will be influenced by the value of an independent variable. The goal of the experiment is to determine a cause-and-effect relationship between independent and dependent variables—in this case, an effect of nitrogen on plant growth. In the nitrogen/grass experiment, (1) which factor was the independent variable? (2) Which factor was the dependent variable?

- Nearly all types of experiments require a control group and an experimental group. The control group generally is not changed in any way, but remains in a "natural state," while the experimental group is modified in some way to examine the effect of the variable which of interest to the researcher. The control group provides a standard of comparison for the experimental groups. For example, in new drug trials, some patients are given a placebo while others are given doses of the drug being tested. The placebo serves as a control by showing the effect of no drug treatment on the patients. In research terminology, the experimental groups are often referred to as treatments , since each group is treated differently. In the experimental test of the effect of nitrogen on grass growth, what is the control group? In the example of the nitrogen experiment, what is the purpose of a control group?

- In research studies a great deal of emphasis is placed on repetition. It is essential that an experiment or study include enough subjects or enough observations for the researcher to make valid conclusions. The two main reasons why repetition is important in scientific studies are (1) variation among subjects or samples and (2) measurement error.

Variation among Subjects

There is a great deal of variation in nature. In a group of experimental subjects, much of this variation may have little to do with the variables being studied, but could still affect the outcome of the experiment in unpredicted ways. For example, in an experiment designed to test the effects of alcohol dose levels on reflex time in 18- to 22-year-old males, there would be significant variation among individual responses to various doses of alcohol. Some of this variation might be due to differences in genetic make-up, to varying levels of previous alcohol use, or any number of factors unknown to the researcher.

Because what the researcher wants to discover is average dose level effects for this group, he must run the test on a number of different subjects. Suppose he performed the test on only 10 individuals. Do you think the average response calculated would be the same as the average response of all 18- to 22-year-old males? What if he tests 100 individuals, or 1,000? Do you think the average he comes up with would be the same in each case? Chances are it would not be. So which average would you predict would be most representative of all 18- to 22-year-old males?

A basic rule of statistics is, the more observations you make, the closer the average of those observations will be to the average for the whole population you are interested in. This is because factors that vary among a population tend to occur most commonly in the middle range, and least commonly at the two extremes. Take human height for example. Although you may find a man who is 7 feet tall, or one who is 4 feet tall, most men will fall somewhere between 5 and 6 feet in height. The more men we measure to determine average male height, the less effect those uncommon extreme (tall or short) individuals will tend to impact the average. Thus, one reason why repetition is so important in experiments is that it helps to assure that the conclusions made will be valid not only for the individuals tested, but also for the greater population those individuals represent.

"The use of a sample (or subset) of a population, an event, or some other aspect of nature for an experimental group that is not large enough to be representative of the whole" is called sampling error (Starr, Cecie, Biology: Concepts and Applications , 4 th ed. [Pacific Cove: Brooks/Cole, 2000], glossary). If too few samples or subjects are used in an experiment, the researcher may draw incorrect conclusions about the population those samples or subjects represent.

Use the jellybean activity below to see a simple demonstration of samping error.

Directions: There are 400 jellybeans in the jar. If you could not see the jar and you initially chose 1 green jellybean from the jar, you might assume the jar only contains green jelly beans. The jar actually contains both green and black jellybeans. Use the "pick 1, 5, or 10" buttons to create your samples. For example, use the "pick" buttons now to create samples of 2, 13, and 27 jellybeans. After you take each sample, try to predict the ratio of green to black jellybeans in the jar. How does your prediction of the ratio of green to black jellybeans change as your sample changes?

Measurement Error

The second reason why repetition is necessary in research studies has to do with measurement error. Measurement error may be the fault of the researcher, a slight difference in measuring techniques among one or more technicians, or the result of limitations or glitches in measuring equipment. Even the most careful researcher or the best state-of-the-art equipment will make some mistakes in measuring or recording data. Another way of looking at this is to say that, in any study, some measurements will be more accurate than others will. If the researcher is conscientious and the equipment is good, the majority of measurements will be highly accurate, some will be somewhat inaccurate, and a few may be considerably inaccurate. In this case, the same reasoning used above also applies here: the more measurements taken, the less effect a few inaccurate measurements will have on the overall average.

Step 4: Data Analysis

In any experiment, observations are made, and often, measurements are taken. Measurements and observations recorded in an experiment are referred to as data . The data collected must relate to the hypothesis being tested. Any differences between experimental and control groups must be expressed in some way (often quantitatively) so that the groups may be compared. Graphs and charts are often used to visualize the data and to identify patterns and relationships among the variables.

Statistics is the branch of mathematics that deals with interpretation of data. Data analysis refers to statistical methods of determining whether any differences between the control group and experimental groups are too great to be attributed to chance alone. Although a discussion of statistical methods is beyond the scope of this tutorial, the data analysis step is crucial because it provides a somewhat standardized means for interpreting data. The statistical methods of data analysis used, and the results of those analyses, are always included in the publication of scientific research. This convention limits the subjective aspects of data interpretation and allows scientists to scrutinize the working methods of their peers.

Why is data analysis an important step in the scientific method?

Step 5: Stating Conclusions

The conclusions made in a scientific experiment are particularly important. Often, the conclusion is the only part of a study that gets communicated to the general public. As such, it must be a statement of reality, based upon the results of the experiment. To assure that this is the case, the conclusions made in an experiment must (1) relate back to the hypothesis being tested, (2) be limited to the population under study, and (3) be stated as probabilities.

The hypothesis that is being tested will be compared to the data collected in the experiment. If the experimental results contradict the hypothesis, it is rejected and further testing of that hypothesis under those conditions is not necessary. However, if the hypothesis is not shown to be wrong, that does not conclusively prove that it is right! In scientific terms, the hypothesis is said to be "supported by the data." Further testing will be done to see if the hypothesis is supported under a number of trials and under different conditions.

If the hypothesis holds up to extensive testing then the temptation is to claim that it is correct. However, keep in mind that the number of experiments and observations made will only represent a subset of all the situations in which the hypothesis may potentially be tested. In other words, experimental data will only show part of the picture. There is always the possibility that a further experiment may show the hypothesis to be wrong in some situations. Also, note that the limits of current knowledge and available technologies may prevent a researcher from devising an experiment that would disprove a particular hypothesis.

The researcher must be sure to limit his or her conclusions to apply only to the subjects tested in the study. If a particular species of fish is shown to consume their young 90 percent of the time when raised in captivity, that doesn't necessarily mean that all fish will do so, or that this fish's behavior would be the same in its native habitat.

Finally, the conclusions of the experiment are generally stated as probabilities. A careful scientist would never say, "drug x kills cancer cells;" she would more likely say, "drug x was shown to destroy 85 percent of cancerous skin cells in rats in lab trials." Notice how very different these two statements are. There is a tendency in the media and in the general public to gravitate toward the first statement. This makes a terrific headline and is also easy to interpret; it is absolute. Remember though, in science conclusions must be confined to the population under study; broad generalizations should be avoided. The second statement is sound science. There is data to back it up. Later studies may reveal a more universal effect of the drug on cancerous cells, or they may not. Most researchers would be unwilling to stake their reputations on the first statement.

As a student, you should read and interpret popular press articles about research studies very carefully. From the text, can you determine how the experiment was set up and what variables were measured? Are the observations and data collected appropriate to the hypothesis being tested? Are the conclusions supported by the data? Are the conclusions worded in a scientific context (as probability statements) or are they generalized for dramatic effect? In any researched-based assignment, it is a good idea to refer to the original publication of a study (usually found in professional journals) and to interpret the facts for yourself.

Qualities of a Good Experiment

- narrowly defined subjects

- all subjects treated alike except for the factor or variable being studied

- a control group is used for comparison

- measurements related to the factors being studied are carefully recorded

- enough samples or subjects are used so that conclusions are valid for the population of interest

- conclusions made relate back to the hypothesis, are limited to the population being studied, and are stated in terms of probabilities

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- About This Blog

- Official PLOS Blog

- EveryONE Blog

- Speaking of Medicine

- PLOS Biologue

- Absolutely Maybe

- DNA Science

- PLOS ECR Community

- All Models Are Wrong

- About PLOS Blogs

A Guide to Using the Scientific Method in Everyday Life

The scientific method —the process used by scientists to understand the natural world—has the merit of investigating natural phenomena in a rigorous manner. Working from hypotheses, scientists draw conclusions based on empirical data. These data are validated on large-scale numbers and take into consideration the intrinsic variability of the real world. For people unfamiliar with its intrinsic jargon and formalities, science may seem esoteric. And this is a huge problem: science invites criticism because it is not easily understood. So why is it important, then, that every person understand how science is done?

Because the scientific method is, first of all, a matter of logical reasoning and only afterwards, a procedure to be applied in a laboratory.

Individuals without training in logical reasoning are more easily victims of distorted perspectives about themselves and the world. An example is represented by the so-called “ cognitive biases ”—systematic mistakes that individuals make when they try to think rationally, and which lead to erroneous or inaccurate conclusions. People can easily overestimate the relevance of their own behaviors and choices. They can lack the ability to self-estimate the quality of their performances and thoughts . Unconsciously, they could even end up selecting only the arguments that support their hypothesis or beliefs . This is why the scientific framework should be conceived not only as a mechanism for understanding the natural world, but also as a framework for engaging in logical reasoning and discussion.

A brief history of the scientific method

The scientific method has its roots in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Philosophers Francis Bacon and René Descartes are often credited with formalizing the scientific method because they contrasted the idea that research should be guided by metaphysical pre-conceived concepts of the nature of reality—a position that, at the time, was highly supported by their colleagues . In essence, Bacon thought that inductive reasoning based on empirical observation was critical to the formulation of hypotheses and the generation of new understanding : general or universal principles describing how nature works are derived only from observations of recurring phenomena and data recorded from them. The inductive method was used, for example, by the scientist Rudolf Virchow to formulate the third principle of the notorious cell theory , according to which every cell derives from a pre-existing one. The rationale behind this conclusion is that because all observations of cell behavior show that cells are only derived from other cells, this assertion must be always true.

Inductive reasoning, however, is not immune to mistakes and limitations. Referring back to cell theory, there may be rare occasions in which a cell does not arise from a pre-existing one, even though we haven’t observed it yet—our observations on cell behavior, although numerous, can still benefit from additional observations to either refute or support the conclusion that all cells arise from pre-existing ones. And this is where limited observations can lead to erroneous conclusions reasoned inductively. In another example, if one never has seen a swan that is not white, they might conclude that all swans are white, even when we know that black swans do exist, however rare they may be.

The universally accepted scientific method, as it is used in science laboratories today, is grounded in hypothetico-deductive reasoning . Research progresses via iterative empirical testing of formulated, testable hypotheses (formulated through inductive reasoning). A testable hypothesis is one that can be rejected (falsified) by empirical observations, a concept known as the principle of falsification . Initially, ideas and conjectures are formulated. Experiments are then performed to test them. If the body of evidence fails to reject the hypothesis, the hypothesis stands. It stands however until and unless another (even singular) empirical observation falsifies it. However, just as with inductive reasoning, hypothetico-deductive reasoning is not immune to pitfalls—assumptions built into hypotheses can be shown to be false, thereby nullifying previously unrejected hypotheses. The bottom line is that science does not work to prove anything about the natural world. Instead, it builds hypotheses that explain the natural world and then attempts to find the hole in the reasoning (i.e., it works to disprove things about the natural world).

How do scientists test hypotheses?

Controlled experiments

The word “experiment” can be misleading because it implies a lack of control over the process. Therefore, it is important to understand that science uses controlled experiments in order to test hypotheses and contribute new knowledge. So what exactly is a controlled experiment, then?

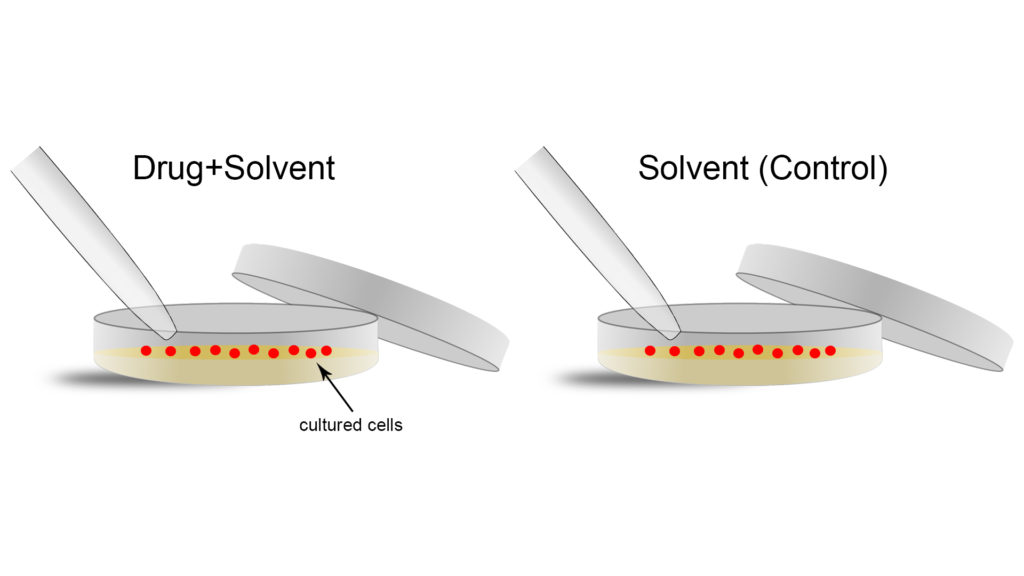

Let us take a practical example. Our starting hypothesis is the following: we have a novel drug that we think inhibits the division of cells, meaning that it prevents one cell from dividing into two cells (recall the description of cell theory above). To test this hypothesis, we could treat some cells with the drug on a plate that contains nutrients and fuel required for their survival and division (a standard cell biology assay). If the drug works as expected, the cells should stop dividing. This type of drug might be useful, for example, in treating cancers because slowing or stopping the division of cells would result in the slowing or stopping of tumor growth.

Although this experiment is relatively easy to do, the mere process of doing science means that several experimental variables (like temperature of the cells or drug, dosage, and so on) could play a major role in the experiment. This could result in a failed experiment when the drug actually does work, or it could give the appearance that the drug is working when it is not. Given that these variables cannot be eliminated, scientists always run control experiments in parallel to the real ones, so that the effects of these other variables can be determined. Control experiments are designed so that all variables, with the exception of the one under investigation, are kept constant. In simple terms, the conditions must be identical between the control and the actual experiment.

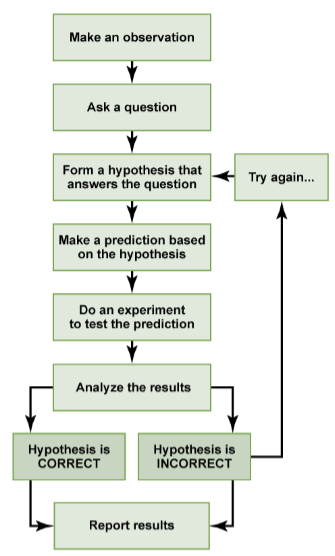

Coming back to our example, when a drug is administered it is not pure. Often, it is dissolved in a solvent like water or oil. Therefore, the perfect control to the actual experiment would be to administer pure solvent (without the added drug) at the same time and with the same tools, where all other experimental variables (like temperature, as mentioned above) are the same between the two (Figure 1). Any difference in effect on cell division in the actual experiment here can be attributed to an effect of the drug because the effects of the solvent were controlled.

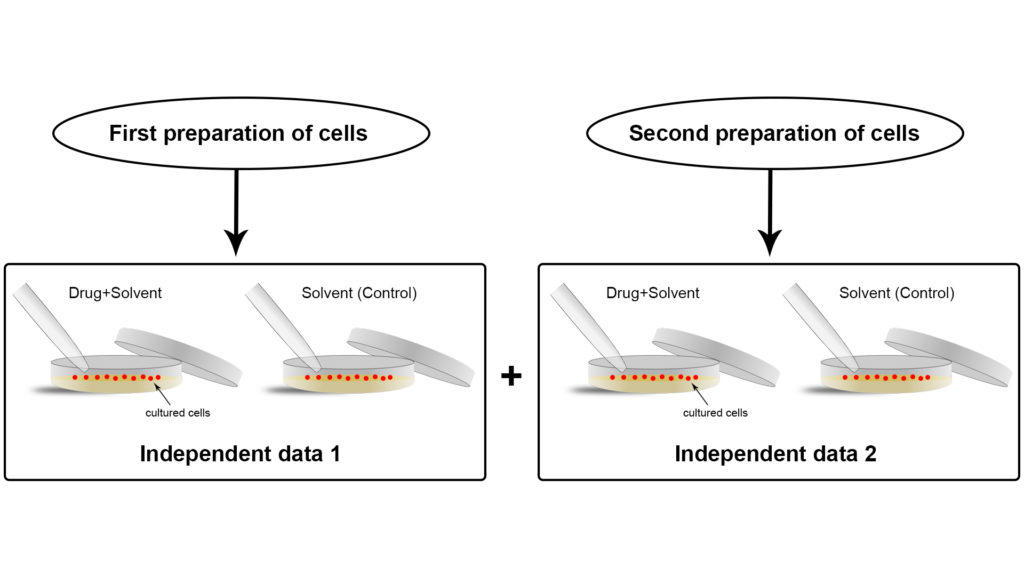

In order to provide evidence of the quality of a single, specific experiment, it needs to be performed multiple times in the same experimental conditions. We call these multiple experiments “replicates” of the experiment (Figure 2). The more replicates of the same experiment, the more confident the scientist can be about the conclusions of that experiment under the given conditions. However, multiple replicates under the same experimental conditions are of no help when scientists aim at acquiring more empirical evidence to support their hypothesis. Instead, they need independent experiments (Figure 3), in their own lab and in other labs across the world, to validate their results.

Often times, especially when a given experiment has been repeated and its outcome is not fully clear, it is better to find alternative experimental assays to test the hypothesis.

Applying the scientific approach to everyday life

So, what can we take from the scientific approach to apply to our everyday lives?

A few weeks ago, I had an agitated conversation with a bunch of friends concerning the following question: What is the definition of intelligence?

Defining “intelligence” is not easy. At the beginning of the conversation, everybody had a different, “personal” conception of intelligence in mind, which – tacitly – implied that the conversation could have taken several different directions. We realized rather soon that someone thought that an intelligent person is whoever is able to adapt faster to new situations; someone else thought that an intelligent person is whoever is able to deal with other people and empathize with them. Personally, I thought that an intelligent person is whoever displays high cognitive skills, especially in abstract reasoning.

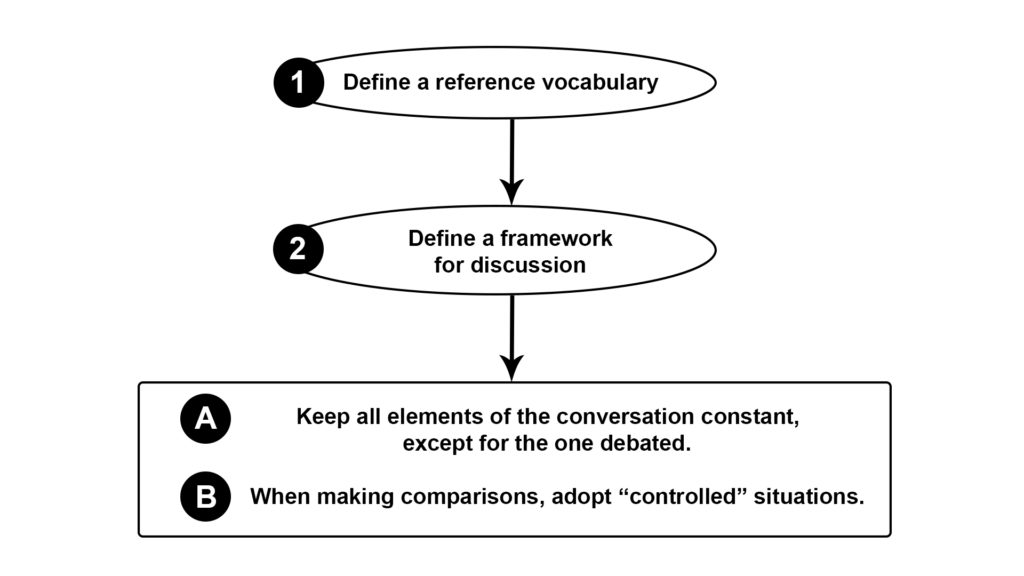

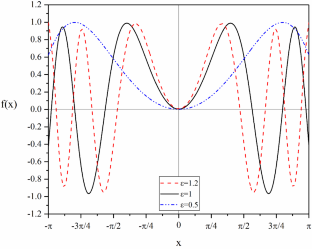

The scientific method has the merit of providing a reference system, with precise protocols and rules to follow. Remember: experiments must be reproducible, which means that an independent scientists in a different laboratory, when provided with the same equipment and protocols, should get comparable results. Fruitful conversations as well need precise language, a kind of reference vocabulary everybody should agree upon, in order to discuss about the same “content”. This is something we often forget, something that was somehow missing at the opening of the aforementioned conversation: even among friends, we should always agree on premises, and define them in a rigorous manner, so that they are the same for everybody. When speaking about “intelligence”, we must all make sure we understand meaning and context of the vocabulary adopted in the debate (Figure 4, point 1). This is the first step of “controlling” a conversation.

There is another downside that a discussion well-grounded in a scientific framework would avoid. The mistake is not structuring the debate so that all its elements, except for the one under investigation, are kept constant (Figure 4, point 2). This is particularly true when people aim at making comparisons between groups to support their claim. For example, they may try to define what intelligence is by comparing the achievements in life of different individuals: “Stephen Hawking is a brilliant example of intelligence because of his great contribution to the physics of black holes”. This statement does not help to define what intelligence is, simply because it compares Stephen Hawking, a famous and exceptional physicist, to any other person, who statistically speaking, knows nothing about physics. Hawking first went to the University of Oxford, then he moved to the University of Cambridge. He was in contact with the most influential physicists on Earth. Other people were not. All of this, of course, does not disprove Hawking’s intelligence; but from a logical and methodological point of view, given the multitude of variables included in this comparison, it cannot prove it. Thus, the sentence “Stephen Hawking is a brilliant example of intelligence because of his great contribution to the physics of black holes” is not a valid argument to describe what intelligence is. If we really intend to approximate a definition of intelligence, Steven Hawking should be compared to other physicists, even better if they were Hawking’s classmates at the time of college, and colleagues afterwards during years of academic research.

In simple terms, as scientists do in the lab, while debating we should try to compare groups of elements that display identical, or highly similar, features. As previously mentioned, all variables – except for the one under investigation – must be kept constant.

This insightful piece presents a detailed analysis of how and why science can help to develop critical thinking.

In a nutshell

Here is how to approach a daily conversation in a rigorous, scientific manner:

- First discuss about the reference vocabulary, then discuss about the content of the discussion. Think about a researcher who is writing down an experimental protocol that will be used by thousands of other scientists in varying continents. If the protocol is rigorously written, all scientists using it should get comparable experimental outcomes. In science this means reproducible knowledge, in daily life this means fruitful conversations in which individuals are on the same page.

- Adopt “controlled” arguments to support your claims. When making comparisons between groups, visualize two blank scenarios. As you start to add details to both of them, you have two options. If your aim is to hide a specific detail, the better is to design the two scenarios in a completely different manner—it is to increase the variables. But if your intention is to help the observer to isolate a specific detail, the better is to design identical scenarios, with the exception of the intended detail—it is therefore to keep most of the variables constant. This is precisely how scientists ideate adequate experiments to isolate new pieces of knowledge, and how individuals should orchestrate their thoughts in order to test them and facilitate their comprehension to others.

Not only the scientific method should offer individuals an elitist way to investigate reality, but also an accessible tool to properly reason and discuss about it.

Edited by Jason Organ, PhD, Indiana University School of Medicine.

Simone is a molecular biologist on the verge of obtaining a doctoral title at the University of Ulm, Germany. He is Vice-Director at Culturico (https://culturico.com/), where his writings span from Literature to Sociology, from Philosophy to Science. His writings recently appeared in Psychology Today, openDemocracy, Splice Today, Merion West, Uncommon Ground and The Society Pages. Follow Simone on Twitter: @simredaelli

- Pingback: Case Studies in Ethical Thinking: Day 1 | Education & Erudition

This has to be the best article I have ever read on Scientific Thinking. I am presently writing a treatise on how Scientific thinking can be adopted to entreat all situations.And how, a 4 year old child can be taught to adopt Scientific thinking, so that, the child can look at situations that bothers her and she could try to think about that situation by formulating the right questions. She may not have the tools to find right answers? But, forming questions by using right technique ? May just make her find a way to put her mind to rest even at that level. That is why, 4 year olds are often “eerily: (!)intelligent, I have iften been intimidated and plain embarrassed to see an intelligent and well spoken 4 year old deal with celibrity ! Of course, there are a lot of variables that have to be kept in mind in order to train children in such controlled thinking environment, as the screenplay of little Sheldon shows. Thanking the author with all my heart – #ershadspeak #wearescience #weareallscientists Ershad Khandker

Simone, thank you for this article. I have the idea that I want to apply what I learned in Biology to everyday life. You addressed this issue, and have given some basic steps in using the scientific method.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email for the next time I comment.

By Ana Santos-Carvalho and Carolina Lebre, edited by Andrew S. Cale Excessive use of technical jargon can be a significant barrier to…

By Ryan McRae and Briana Pobiner, edited by Andrew S. Cale In 2023, the field of human evolution benefited from a plethora…

By Elizabeth Fusco, edited by Michael Liesen Infection and pandemics have never been more relevant globally, and zombies have long been used…

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1.1: The Scientific Method

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 33373

- Melissa Ha, Maria Morrow, & Kammy Algiers

- Yuba College, College of the Redwoods, & Ventura College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Learning Objectives

- Identify the shared characteristics of the natural sciences.

- Summarize the steps of the scientific method.

- Compare inductive reasoning with deductive reasoning.

- Describe the goals of basic science and applied science.

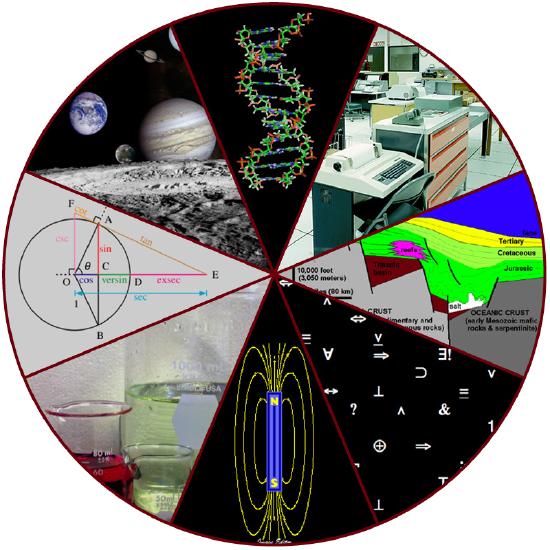

The Process of Science

Science includes such diverse fields as astronomy, biology, computer sciences, geology, logic, physics, chemistry, and mathematics (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). However, those fields of science related to the physical world and its phenomena and processes are considered natural sciences . Natural sciences could be categorized as astronomy, biology, chemistry, earth science, and physics. One can divide natural sciences further into life sciences, which study living things and include biology, and physical sciences, which study nonliving matter and include astronomy, geology, physics, and chemistry. Some disciplines such as biophysics and biochemistry build on both life and physical sciences and are interdisciplinary. Natural sciences are sometimes referred to as “hard science” because they rely on the use of quantitative data; social sciences that study society and human behavior are more likely to use qualitative assessments to drive investigations and findings.

Not surprisingly, the natural science of biology has many branches or subdisciplines. Cell biologists study cell structure and function, while biologists who study anatomy investigate the structure of an entire organism. Those biologists studying physiology, however, focus on the internal functioning of an organism. Some areas of biology focus on only particular types of living things. For example, botanists explore plants, while zoologists specialize in animals.

Scientific Reasoning

One thing is common to all forms of science: an ultimate goal “to know.” Curiosity and inquiry are the driving forces for the development of science. Scientists seek to understand the world and the way it operates. To do this, they use two methods of logical thinking: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses related observations to arrive at a general conclusion. This type of reasoning is common in descriptive science. A life scientist such as a biologist makes observations and records them. These data can be qualitative (descriptive) or quantitative (numeric), and the raw data can be supplemented with drawings, pictures, photos, or videos. From many observations, the scientist can infer conclusions (inductions) based on evidence. Inductive reasoning involves formulating generalizations inferred from careful observation and the analysis of a large amount of data.

Deductive reasoning , or deduction, is the type of logic used in hypothesis-based science. In deductive reason, the pattern of thinking moves in the opposite direction as compared to inductive reasoning; that is, specific results are predicted from a general premise. Deductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses a general principle or law to forecast specific results. From those general principles, a scientist can extrapolate and predict the specific results that would be valid as long as the general principles are valid. Studies in climate change can illustrate this type of reasoning. For example, scientists may predict that if the climate becomes warmer in a particular region, then the distribution of plants and animals should change. These predictions have been made and tested, and many such changes have been found, such as the modification of arable areas for agriculture, with change based on temperature averages.

Inductive and deductive reasoning are often used in tandem to advance scientific knowledge (Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)) . Both types of logical thinking are related to the two main pathways of scientific study: descriptive science and hypothesis-based science. Descriptive (or discovery) science , which is usually inductive, aims to observe, explore, and discover, while hypothesis-based science , which is usually deductive, begins with a specific question or problem and a potential answer or solution that one can test. The boundary between these two forms of study is often blurred, and most scientific endeavors combine both approaches.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Here is an example of how the two types of reasoning might be used in similar situations.

In inductive reasoning, where a conclusion is drawn from a number of observations, one might observe that members of a species are not all the same, individuals compete for resources, and species are generally adapted to their environment. This observation could then lead to the conclusion that individuals most adapted to their environment are more likely to survive and pass their traits to the next generation.

In deductive reasoning, which uses a general premise to predict a specific result, one might start with that conclusion as a general premise, then predict the results. For example, from that premise, one might predict that if the average temperature in an ecosystem increases due to climate change, individuals better adapted to warmer temperatures will outcompete those that are not. A scientist could then design a study to test this prediction.

The Scientific Method

Biologists study the living world by posing questions about it and seeking science-based responses. The scientific method is a method of research with defined steps that include experiments and careful observation. The scientific method was used even in ancient times, but it was first documented by England’s Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626; Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), who set up inductive methods for scientific inquiry. The scientific method is not exclusively used by biologists but can be applied to almost all fields of study as a logical, rational problem-solving method.

It is important to note that even though there are specific steps to the scientific method, the process of science is often more fluid, with scientists going back and forth between steps until they reach their conclusions.

Observation and Question

Scientists are good observers. In the field of biology, naturalists will often will make an observation that leads to a question. A naturalist is a person who studies nature. Naturalists often describe structures, processes, and behavior, either with their eyes or with the use of a tool such as a microscope. A naturalist may not conduct experiments, but they may ask many good questions that can lead to experimentation. Scientists are also very curious. They will research for known answers to their questions or run experiments to learn the answer to their questions.

Let’s think about a simple problem that starts with an observation and apply the scientific method to solve the problem. One Monday morning, a student arrives at class and quickly discovers that the classroom is too warm. That is an observation that also describes a problem: the classroom is too warm. The student then asks a question: “Why is the classroom so warm?”

Proposing a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an educated guess or a suggested explanation for an event, which can be tested. Sometimes, more than one hypothesis may be proposed. Once a hypothesis has been selected, the student can make a prediction. A prediction is similar to a hypothesis but it typically has the format “If . . . then . . . .”.

For example, one hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because no one turned on the air conditioning.” However, there could be other responses to the question, and therefore one may propose other hypotheses. A second hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because there is a power failure, and so the air conditioning doesn’t work.” In this case, you would have to test both hypotheses to see if either one could be supported with data.

A hypothesis may become a verified theory . This can happen if it has been repeatedly tested and confirmed, is general, and has inspired many other hypotheses, facts, and experimentations. Not all hypotheses will become theories.

Testing a Hypothesis

A valid hypothesis must be testable. It should also be falsifiable , meaning that it can be disproven by experimental results. Importantly, science does not claim to “prove” anything because scientific understandings are always subject to modification with further information. This step—openness to disproving ideas—is what distinguishes sciences from non-sciences. The presence of the supernatural, for instance, is neither testable nor falsifiable. To test a hypothesis, a researcher will conduct one or more experiments designed to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. Each experiment will have one or more variables and one or more controls. A variable is any part of the experiment that can vary or change during the experiment. The control group contains every feature of the experimental group except that it was not manipulated. Therefore, if the results of the experimental group differ from the control group, the difference must be due to the hypothesized manipulation, rather than some outside factor. Look for the variables and controls in the examples that follow. To test the first hypothesis, the student would find out if the air conditioning is on. If the air conditioning is turned on but does not work, there should be another reason, and this hypothesis should be rejected. To test the second hypothesis, the student could check if the lights in the classroom are functional. If so, there is no power failure, and this hypothesis should be rejected. Each hypothesis should be tested by carrying out appropriate experiments. Be aware that rejecting one hypothesis does not determine whether or not the other hypotheses can be accepted; it simply eliminates one hypothesis that is not valid (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Using the scientific method, the hypotheses that are inconsistent with experimental data are rejected.

While this “warm classroom” example is based on observational results, other hypotheses and experiments might have clearer controls. For instance, a student might attend class on Monday and realize she had difficulty concentrating on the lecture. One observation to explain this occurrence might be, “When I eat breakfast before class, I am better able to pay attention.” The student could then design an experiment with a control to test this hypothesis.

Visual Connection

The scientific method may seem too rigid and structured. It is important to keep in mind that, although scientists often follow this sequence, there is flexibility. Sometimes an experiment leads to conclusions that favor a change in approach; often, an experiment brings entirely new scientific questions to the puzzle. Many times, science does not operate in a linear fashion; instead, scientists continually draw inferences and make generalizations, finding patterns as their research proceeds. Scientific reasoning is more complex than the scientific method alone suggests. Notice, too, that the scientific method can be applied to solving problems that aren’t necessarily scientific in nature (Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

In the example below, the scientific method is used to solve an everyday problem. Match the scientific method steps (numbered items) with the process of solving the everyday problem (lettered items). Based on the results of the experiment, is the hypothesis correct? If it is incorrect, propose some alternative hypotheses.

Steps of the Scientific Method

- Observation

- Hypothesis (answer)

Process of Solving an Everyday Problem

- There is something wrong with the electrical outlet.

- If something is wrong with the outlet, my coffee maker also won’t work when plugged into it.

- My toaster doesn’t toast my bread.

- I plug my coffee maker into the outlet.

- My coffee maker works.

- Why doesn’t my toaster work?

Two Types of Science: Basic Science and Applied Science

The scientific community has been debating for the last few decades about the value of different types of science. Is it valuable to pursue science for the sake of simply gaining knowledge, or does scientific knowledge only have worth if we can apply it to solving a specific problem or to bettering our lives? This question focuses on the differences between two types of science: basic science and applied science.

Basic science or “pure” science seeks to expand knowledge regardless of the short-term application of that knowledge. It is not focused on developing a product or a service of immediate public or commercial value. The immediate goal of basic science is knowledge for knowledge’s sake, though this does not mean that, in the end, it may not result in a practical application.

In contrast, applied science or “technology,” aims to use science to solve real-world problems, making it possible, for example, to improve a crop yield or find a cure for a particular disease. In applied science, the problem is usually defined for the researcher.

Some individuals may perceive applied science as “useful” and basic science as “useless.” A question these people might pose to a scientist advocating knowledge acquisition would be, “What for?” A careful look at the history of science, however, reveals that basic knowledge has resulted in many remarkable applications of great value. Many scientists think that a basic understanding of science is necessary before an application is developed; therefore, applied science relies on the results generated through basic science. Other scientists think that it is time to move on from basic science and instead to find solutions to actual problems. Both approaches are valid. It is true that there are problems that demand immediate attention; however, few solutions would be found without the help of the wide knowledge foundation generated through basic science.

One example of how basic and applied science can work together to solve practical problems occurred after the discovery of DNA structure led to an understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing DNA replication. Strands of DNA, unique in every human, are found in our cells, where they provide the instructions necessary for life. During DNA replication, DNA makes new copies of itself, shortly before a cell divides. Understanding the mechanisms of DNA replication enabled scientists to develop laboratory techniques that are now used to identify genetic diseases, pinpoint individuals who were at a crime scene, and determine paternity. Without basic science, it is unlikely that applied science would exist.

Another example of the link between basic and applied research is the Human Genome Project, a study in which each human chromosome was analyzed and mapped to determine the precise sequence of DNA subunits and the exact location of each gene. (The gene is the basic unit of heredity; an individual’s complete collection of genes is their genome.) Other less complex organisms have also been studied as part of this project in order to gain a better understanding of human chromosomes. The Human Genome Project (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) relied on basic research carried out with simple organisms and, later, with the human genome. An important end goal eventually became using the data for applied research, seeking cures and early diagnoses for genetically related diseases.

While research efforts in both basic science and applied science are usually carefully planned, it is important to note that some discoveries are made by serendipity , that is, by means of a fortunate accident or a lucky surprise. Penicillin was discovered when biologist Alexander Fleming accidentally left a petri dish of Staphylococcus bacteria open. An unwanted mold grew on the dish, killing the bacteria. The mold turned out to be Penicillium , and a new antibiotic was discovered. Even in the highly organized world of science, luck—when combined with an observant, curious mind—can lead to unexpected breakthroughs.

Reporting Scientific Work

Whether scientific research is basic science or applied science, scientists must share their findings in order for other researchers to expand and build upon their discoveries. Collaboration with other scientists—when planning, conducting, and analyzing results—are all important for scientific research. For this reason, important aspects of a scientist’s work are communicating with peers and disseminating results to peers. Scientists can share results by presenting them at a scientific meeting or conference (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)), but this approach can reach only the select few who are present. Instead, most scientists present their results in peer-reviewed manuscripts that are published in scientific journals. Peer-reviewed manuscripts are scientific papers that are reviewed by a scientist’s colleagues, or peers. These colleagues are qualified individuals, often experts in the same research area, who judge whether or not the scientist’s work is suitable for publication. The process of peer review helps to ensure that the research described in a scientific paper or grant proposal is original, significant, logical, and thorough. Grant proposals, which are requests for research funding, are also subject to peer review. Scientists publish their work so other scientists can reproduce their experiments under similar or different conditions to expand on the findings. The experimental results must be consistent with the findings of other scientists.

A scientific paper is very different from creative writing. Although creativity is required to design experiments, there are fixed guidelines when it comes to presenting scientific results. First, scientific writing must be brief, concise, and accurate. A scientific paper needs to be succinct but detailed enough to allow peers to reproduce the experiments.

The scientific paper consists of several specific sections—introduction, materials and methods, results, and discussion. This structure is sometimes called the “IMRaD” format, an acronym for Introduction, Method, Results, and Discussion. There are usually acknowledgment and reference sections as well as an abstract (a concise summary) at the beginning of the paper. There might be additional sections depending on the type of paper and the journal where it will be published; for example, some review papers require an outline.

The introduction starts with brief, but broad, background information about what is known in the field. A good introduction also gives the rationale of the work; it justifies the work carried out and also briefly mentions the end of the paper, where the hypothesis or research question driving the research will be presented. The introduction refers to the published scientific work of others and therefore requires citations following the style of the journal. Using the work or ideas of others without proper citation is considered plagiarism .

The materials and methods section includes a complete and accurate description of the substances used, and the method and techniques used by the researchers to gather data. The description should be thorough enough to allow another researcher to repeat the experiment and obtain similar results, but it does not have to be verbose. This section will also include information on how measurements were made and what types of calculations and statistical analyses were used to examine raw data. Although the materials and methods section gives an accurate description of the experiments, it does not discuss them.

Some journals require a results section followed by a discussion section, but it is more common to combine both. If the journal does not allow the combination of both sections, the results section simply narrates the findings without any further interpretation. The results are presented by means of tables or graphs, but no duplicate information should be presented. In the discussion section, the researcher will interpret the results, describe how variables may be related, and attempt to explain the observations. It is indispensable to conduct an extensive literature search to put the results in the context of previously published scientific research. Therefore, proper citations are included in this section as well.

Finally, the conclusion section summarizes the importance of the experimental findings. While the scientific paper almost certainly answered one or more scientific questions that were stated, any good research should lead to more questions. Therefore, a well-done scientific paper leaves doors open for the researcher and others to continue and expand on the findings.

Review articles do not follow the IMRaD format because they do not present original scientific findings (they are not primary literature); instead, they summarize and comment on findings that were published as primary literature and typically include extensive reference sections.

Attributions

Curated and authored by Kammy Algiers using 1.2 (The Process of Science) from Biology 2e by OpenStax (licensed CC-BY ).

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1.6: Scientific Problem Solving

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 419240

How can we use problem solving in our everyday routines?

One day you wake up and realize your clock radio did not turn on to get you out of bed. You are puzzled, so you decide to find out what happened. You list three possible explanations:

- There was a power failure and your radio cannot turn on.

- Your little sister turned it off as a joke.

- You did not set the alarm last night.

Upon investigation, you find that the clock is on, so there is no power failure. Your little sister was spending the night with a friend and could not have turned the alarm off. You notice that the alarm is not set—your forgetfulness made you late. You have used the scientific method to answer a question.

Scientific Problem Solving

Humans have always wondered about the world around them. One of the questions of interest was (and still is): what is this world made of? Chemistry has been defined in various ways as the study of matter. What matter consists of has been a source of debate over the centuries. One of the key areas for this debate in the Western world was Greek philosophy.