Problem-solving in Leadership: How to Master the 5 Key Skills

The role of problem-solving in enhancing team morale, the right approach to problem-solving in leadership, developing problem-solving skills in leadership, leadership problem-solving examples.

Other Related Blogs

What’s the Role of Problem-solving in Leadership?

- Getting to the root of the issue: First, Sarah starts by looking at the numbers for the past few months. She identifies the products for which sales are falling. She then attempts to correlate it with the seasonal nature of consumption or if there is any other cause hiding behind the numbers.

- Identifying the sources of the problem: In the next step, Sarah attempts to understand why sales are falling. Is it the entry of a new competitor in the next neighborhood, or have consumption preferences changed over time? She asks some of her present and past customers for feedback to get more ideas.

- Putting facts on the table: Next up, Sarah talks to her sales team to understand their issues. They could be lacking training or facing heavy workloads, impacting their productivity. Together, they come up with a few ideas to improve sales.

- Selection and application: Finally, Sarah and her team pick up a few ideas to work on after analyzing their costs and benefits. They ensure adequate resources, and Sarah provides support by guiding them wherever needed during the planning and execution stage.

- Identifying the root cause of the problem.

- Brainstorming possible solutions.

- Evaluating those solutions to select the best one.

- Implementing it.

- Analytical thinking: Analytical thinking skills refer to a leader’s abilities that help them analyze, study, and understand complex problems. It allows them to dive deeper into the issues impacting their teams and ensures that they can identify the causes accurately.

- Critical Thinking: Critical thinking skills ensure leaders can think beyond the obvious. They enable leaders to question assumptions, break free from biases, and analyze situations and facts for accuracy.

- Creativity: Problems are often not solved straightaway. Leaders need to think out of the box and traverse unconventional routes. Creativity lies at the center of this idea of thinking outside the box and creating pathways where none are apparent.

- Decision-making: Cool, you have three ways to go. But where to head? That’s where decision-making comes into play – fine-tuning analysis and making the choices after weighing the pros and cons well.

- Effective Communication: Last but not at the end lies effective communication that brings together multiple stakeholders to solve a problem. It is an essential skill to collaborate with all the parties in any issue. Leaders need communication skills to share their ideas and gain support for them.

How do Leaders Solve Problems?

Business turnaround, crisis management, team building.

Process improvement

Ace performance reviews with strong feedback skills..

Master the art of constructive feedback by reviewing your skills with a free assessment now.

Why is problem solving important?

What is problem-solving skills in management, how do you develop problem-solving skills.

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2024, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

- Choosing Workplace

- Customer Stories

- Workplace for Good

- Getting Started

- Why Workplace

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Future of Work

- How can Workplace help you?

- Business Communication

- Employee Engagement

- Strengthen Culture

- Getting Connected

- Frontline Workers

- Remote and Hybrid Working

- Integrations

- Interactive Demo

- Features at a Glance

- Connect to all your tools

- Workplace & Microsoft

- Integrations directory

- Knowledge Library

- Key Updates

- Auto-Translate

- Safety Center

- Access Codes

- Pricing Plans

- Forrester ROI Study

- Events & Webinars

- Ebooks & Guides

- Employee Experience

- Remote Working

- Team Collaboration

- Productivity

- Become A Partner

- Service & Reseller Partners

- Integrations Partners

- Start Using Workplace

- Mastering Workplace Features

- Workplace Use Cases

- Technical Resources

- Work Academy

- Help Center

- Customer Communities

- What's New in Workplace

- Set up Guides

- Domain Management

- Workplace Integrations

- Account Management

- Authentication

- IT Configuration

- Account Lifecycle

- Security and Governance

- Workplace API

- Getting started

- Using Workplace

- Managing Workplace

- IT and Developer Support

- Get in touch

Problem-solving skills in leadership

Do you find yourself fighting fires on a daily basis it’s time to sharpen your problem-solving skills to become a more effective leader..

What is problem solving in leadership?

To explain how problem solving relates to leadership, it’s best to begin with a basic definition. The Oxford English Dictionary describes problem solving as “the action of finding solutions to difficult or complex issues”.

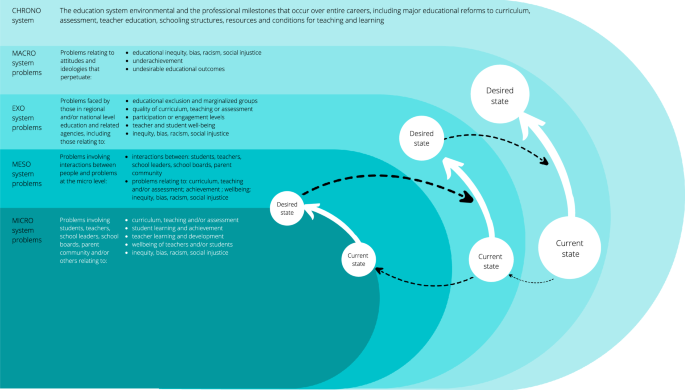

The Chartered Management Institute (CMI) adds a little more color to this. It defines a problem as “the distance between how things currently are and the way they should be. Problem solving forms the ‘bridge’ between these two elements. In order to close the gap, you need to understand the way things are (problem) and the way they ought to be (solution).”

In the workplace, problem solving means dealing with issues or challenges that arise in the course of everyday operations. This could be anything from production delays and customer complaints to skills shortages and employee conflict .

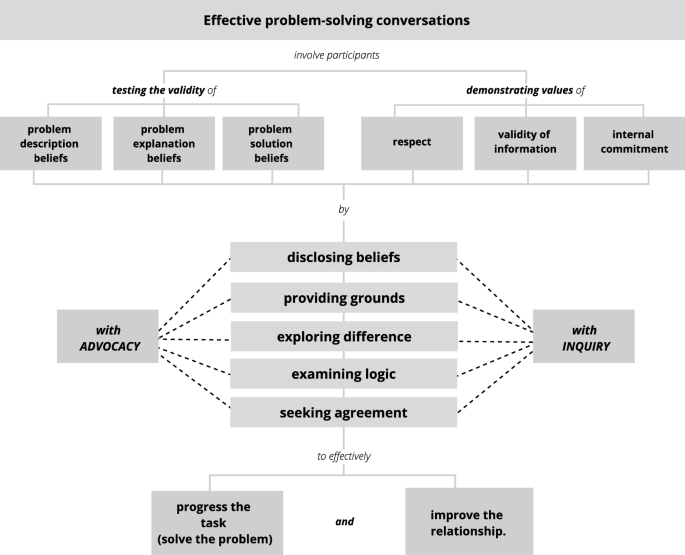

For leaders, the objective is to bring clarity and purpose to problem solving in a way that makes sense for the organization. While the leader has the final say, finding solutions is a collaborative effort that should involve key stakeholders, including employees.

Untangle work with Workplace

From informing everyone about the return to the office to adopting a hybrid way of working, Workplace makes work more simple.

The process of fixing problems

Problem solving leadership should follow these four steps:

Identify the root cause of the problem – do this through fact-finding and getting feedback from those involved.

Brainstorm possible solutions – get ideas from as many people as you can to get a range of perspectives.

Evaluate solutions – draw up a shortlist of workable options and choose the best one.

Implement and evaluate your plan of action – communicate your solution with all stakeholders and explain your reasoning.

As businesses face increasingly complex challenges, some leaders are embracing what the MIT Sloan School of Management calls ‘problem-led leadership’. Instead of concentrating on managing their people, they inspire others through their enthusiasm to solve ‘cool’ problems. While this leadership style won’t be right for every situation, it can work well where innovation and entrepreneurship are needed.

Leaders who problem-solve effectively can improve efficiency , reduce costs, increase customer satisfaction and achieve their strategic goals. If left unresolved, however, problems can spiral and ultimately affect the overall health and performance of your business.

Why is problem solving important in leadership?

The importance of leadership problem-solving skills shouldn’t be underestimated. When you think about it, businesses are beset by processes and interactions that don’t work as well as they could. Having the knowhow – not to mention determination – to overcome such obstacles is vital to make workplaces better for everyone. In fact, a 2022 survey shows that problem solving is among the top five skills UK employees look for in a leader.

Learning how to solve problems proficiently can benefit your organization in many ways. It can help you:

Make better decisions

Being able to solve complex problems with clarity and a rational mindset helps with decision-making. It gives you the confidence to weigh up the pros and cons of each decision before making a final call, without jumping to the wrong conclusion. This ensures the choices you make are right for your team and organization as a whole.

Overcome challenges

No matter how tight a ship you run, you’re always going to come up against obstacles. Challenges are a way of life for businesses, however successful they are.

A leader with good problem-solving skills is able to anticipate issues and have measures in place to deal with them if and when they arise. But they also have the ability to think on their feet and adapt their strategies if needed.

Inspire creativity and innovation

Creativity is useful when trying to solve problems, particularly ones you haven’t experienced before. Leaders who think differently can be great innovators . But they also empower their teams to think outside the box too by creating a safe, non-judgmental environment where all ideas are welcome.

Encourage collaboration

A problem shared is a problem halved, so the saying goes. Successful leaders recognize that problem solving alone is less beneficial than problem solving with a team. This inspires a culture of collaboration , not just between leaders and their team members but between colleagues working together on projects.

Build trust

When your team members know they can rely on you to identify and resolve issues quickly and effectively, it builds trust. They’re also more likely to feel comfortable talking to you if they have a problem of their own that they’re struggling with.

If they’re worried about repercussions, they may avoid sharing it with you. Lack of trust is still an issue in many organizations, with 40% of frontline staff saying they don’t have faith in their leadership, according to Qualtrics .

Reduce risk

Being able to anticipate potential risks and put measures in place to mitigate them makes you better equipped to protect your organization from harm. Having good problem-solving skills in leadership allows you to make informed decisions and avoid costly mistakes, even in times of uncertainty.

Boost morale

Leaders who approach problem solving with positivity and calmness are crucial to keeping team morale high . No one wants a leader who panics at the first sign of trouble. Workers want to feel reassured that they have someone capable in charge who can steer them through times of crisis.

What problems do leaders face?

As a leader, you’re likely to face all manner of setbacks and challenges. In fact, you probably find that hardly a day goes by without some kind of issue cropping up.

Common problems faced by leaders often involve communication barriers, team disagreements, production delays and missed financial targets. To give you an example, below are three common scenarios you might face in the workplace and how to tackle them.

Conflicts between team members

Problem: Cliques have developed and tensions are affecting communication so your team isn’t working as effectively as it could be.

Solution: Settle disputes by encouraging open and honest communication among all team members. Establish roles where each person’s responsibilities and expectations are clearly defined, and hold regular team building sessions to promote unity and togetherness.

Outdated technology hampering production

Problem: Hybrid and remote staff don’t have the right tools to do their job properly, and can’t keep track of who’s working on what, when and from where.

Solution: Evaluate your existing technology and upgrade to newer software and devices, getting feedback from your employees on what they need (52% of workers say the software related to their job is dated and difficult to use). Use a platform with apps that allow teams to collaborate and securely access work information from anywhere.

Customer service complaints

Problem: Customer response times are too slow – your team is taking too long to answer the phone and respond to emails, causing a rise in complaints.

Solution: Establish standard practice for what to do from the moment a customer query is received. Automate repetitive tasks and enable your customers to reach you via multiple channels including email, web chat, phone, social media and text.

What problem-solving skills do leaders need?

Problem solving is something we learn through experience, often by getting it wrong the first time. It requires continual learning, curiosity and agility so you develop a good instinct for what to do when things go wrong. Time is a great teacher, but leadership problem-solving skills can also be honed through workshops, mentoring and training programs.

Some of the key skills leaders need to solve problems include:

Effective communication

Problems can cause anxiety, but it’s vital to stay calm so you don’t transmit a feeling of panic to others. It’s important to establish the facts before clearly relaying the problem to key stakeholders. You’ll also need to inspire the people who are working on the solution to remain focused on the task in hand until it’s resolved. Sometimes, this may involve giving critical feedback and making team members more accountable.

Transparency is key here. When you don’t have open and honest communication across your organization, you develop silos – which can generate more issues than need fixing.

Analytical insight

Your objective should be to find the root cause of the problem. That way, you can find a permanent solution rather than simply papering over the cracks. You’ll need to assess to what extent the issue has affected the overall business by analyzing data, speaking to those involved and looking for distinct patterns of behavior.

Analytical thinking is also important when proposing solutions and taking what you believe to be the right course of action.

Promoting a culture of psychological safety

It’s a leader’s responsibility to create an environment conducive to problem solving. In a safe, open and inclusive workplace, all team members feel comfortable bringing their ideas to the table. No one feels judged or ridiculed for their contributions. Nor do they feel dismissed for questioning the effectiveness of long-established processes and systems.

Not playing the blame game

Mistakes happen.They’re a normal part of growth and development. Instead of pointing fingers when things go wrong, see it as a learning opportunity.

Although you need to identify the cause of an error or problem to solve it effectively – and give feedback where needed – it’s not the same as placing blame. Instead, work towards a solution that ensures the same mistakes don’t keep being repeated.

Emotional intelligence

One of the most important problem-solving skills for leaders is emotional intelligence – the ability to understand emotions and empathize with others. This is crucial when recognizing employees’ problems. An EY Consulting survey found that 90% of US workers believe empathetic leadership leads to greater job satisfaction.

If you approach a problem with anger and frustration, you might make a rash decision or overlook important information. If, on the other hand, you stay calm and measured, you’ll be more inclined to seek feedback to get a broader view of the issue.

A flexible mindset

Problem solving works best when you keep an open mind and aren’t afraid to change direction. Sometimes you’ll need to find a better or more innovative approach to overcoming challenges. A leader with a flexible mindset is always receptive to new ideas and other viewpoints.

It’s clear that problem solving is an essential skill for any leader to have in their armory. So, the next time you face a challenge, take a breath and embrace the opportunity to put your problem-solving leadership abilities to the test.

Keep reading

What is leadership and why is it so important.

- Why successful leadership depends on a growth mindset

- How to transition from manager to leader

Let's Stay Connected

Get the latest news and insights from the frontline of work.

By submitting this form, you agree to receive marketing-related electronic communications from Facebook, including news, events, updates and promotional emails. You may withdraw your consent and unsubscribe from such emails at any time. You also acknowledge that you have read and agree to the Workplace Privacy terms.

Recent posts

Leadership | 11 minute read

What is a leader? Are leaders the same as managers? Can you learn to be a leader? We explore what makes a leader and why good leadership is business critical.

Leadership | 7 minute read

Collaborative leadership: what it is and how it can bring your teams together.

Collaborative leaders believe in bringing diverse teams together to achieve organizational goals, solve problems, make decisions and share information. But what does it really take to be a more collaborative leader? We take a look.

Leadership | 4 minute read

3 lessons leaders can take from life

It's the authentic experiences they have in real life that define who people are and can shape how they lead. Here are three of the best examples.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

- Problem Solving

Problem Solving is a component of Ownership. Within Problem Solving, we also cover key topics including Spotlight on Problem Solving Tools and Techniques, Spotlight on Gap Analysis and Spotlight on Intuition Problem Solving.

- Dimensions of Leadership

Leadership Essentials: Problem Solving

It is often easy to overlook or misunderstand the true nature and cause of problems in the workplace. This can lead to missed learning opportunities, the wrong problem being dealt with, or the symptom being removed but not the cause of the underlying problem. You need to diagnose the situation so that the real problem is accurately identified, and if you define problems accurately you will make them easier and less costly to solve.

‘Leadership Essentials: Problem-Solving’ provides an overview of why problem-solving is essential for leadership capability and includes ‘Top Tips’ on how effective problem-solving can help you become a better leader. The Essentials leaflet is supported by three Spotlights that look at problem-solving in more detail to help you improve your leadership skills:

- Defining the Problem

- Gap Analysis

- Intuition in Problem-Solving

09 February 2018

Spotlight on Gap Analysis

Spotlight on Intuition in Problem Solving

"My own experience is that you get as much information as you can and then you pay attention to your intuition, to your informed instinct"

Colin Powell (Former U.S. Secretary of State and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff)

Spotlight on Problem Solving Tools and Techniques

"If I were given one hour to save the world, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute resolving it." Attributed to Albert Einstein

New to The Institute?

Test your leadership capability, get professional recognition and share your sucess with digital credentials., become a member today .

GET MEMBERSHIP

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Do You Understand the Problem You’re Trying to Solve?

To solve tough problems at work, first ask these questions.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem without taking time to really understand the dilemma we face, according to Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg , an expert in innovation and the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for just one root cause can be misleading.

Key episode topics include: leadership, decision making and problem solving, power and influence, business management.

HBR On Leadership curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock the best in those around you. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the original HBR IdeaCast episode: The Secret to Better Problem Solving (2016)

- Find more episodes of HBR IdeaCast

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR on Leadership , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock the best in those around you.

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But even the most experienced among us can fall into the trap of solving the wrong problem.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg says that all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem – without taking time to really understand what we’re facing.

He’s an expert in innovation, and he’s the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems, by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for one root cause can be misleading. And you’ll learn how to use experimentation and rapid prototyping as problem-solving tools.

This episode originally aired on HBR IdeaCast in December 2016. Here it is.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Welcome to the HBR IdeaCast from Harvard Business Review. I’m Sarah Green Carmichael.

Problem solving is popular. People put it on their resumes. Managers believe they excel at it. Companies count it as a key proficiency. We solve customers’ problems.

The problem is we often solve the wrong problems. Albert Einstein and Peter Drucker alike have discussed the difficulty of effective diagnosis. There are great frameworks for getting teams to attack true problems, but they’re often hard to do daily and on the fly. That’s where our guest comes in.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg is a consultant who helps companies and managers reframe their problems so they can come up with an effective solution faster. He asks the question “Are You Solving The Right Problems?” in the January-February 2017 issue of Harvard Business Review. Thomas, thank you so much for coming on the HBR IdeaCast .

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Thanks for inviting me.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I thought maybe we could start by talking about the problem of talking about problem reframing. What is that exactly?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Basically, when people face a problem, they tend to jump into solution mode to rapidly, and very often that means that they don’t really understand, necessarily, the problem they’re trying to solve. And so, reframing is really a– at heart, it’s a method that helps you avoid that by taking a second to go in and ask two questions, basically saying, first of all, wait. What is the problem we’re trying to solve? And then crucially asking, is there a different way to think about what the problem actually is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I feel like so often when this comes up in meetings, you know, someone says that, and maybe they throw out the Einstein quote about you spend an hour of problem solving, you spend 55 minutes to find the problem. And then everyone else in the room kind of gets irritated. So, maybe just give us an example of maybe how this would work in practice in a way that would not, sort of, set people’s teeth on edge, like oh, here Sarah goes again, reframing the whole problem instead of just solving it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I mean, you’re bringing up something that’s, I think is crucial, which is to create legitimacy for the method. So, one of the reasons why I put out the article is to give people a tool to say actually, this thing is still important, and we need to do it. But I think the really critical thing in order to make this work in a meeting is actually to learn how to do it fast, because if you have the idea that you need to spend 30 minutes in a meeting delving deeply into the problem, I mean, that’s going to be uphill for most problems. So, the critical thing here is really to try to make it a practice you can implement very, very rapidly.

There’s an example that I would suggest memorizing. This is the example that I use to explain very rapidly what it is. And it’s basically, I call it the slow elevator problem. You imagine that you are the owner of an office building, and that your tenants are complaining that the elevator’s slow.

Now, if you take that problem framing for granted, you’re going to start thinking creatively around how do we make the elevator faster. Do we install a new motor? Do we have to buy a new lift somewhere?

The thing is, though, if you ask people who actually work with facilities management, well, they’re going to have a different solution for you, which is put up a mirror next to the elevator. That’s what happens is, of course, that people go oh, I’m busy. I’m busy. I’m– oh, a mirror. Oh, that’s beautiful.

And then they forget time. What’s interesting about that example is that the idea with a mirror is actually a solution to a different problem than the one you first proposed. And so, the whole idea here is once you get good at using reframing, you can quickly identify other aspects of the problem that might be much better to try to solve than the original one you found. It’s not necessarily that the first one is wrong. It’s just that there might be better problems out there to attack that we can, means we can do things much faster, cheaper, or better.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, in that example, I can understand how A, it’s probably expensive to make the elevator faster, so it’s much cheaper just to put up a mirror. And B, maybe the real problem people are actually feeling, even though they’re not articulating it right, is like, I hate waiting for the elevator. But if you let them sort of fix their hair or check their teeth, they’re suddenly distracted and don’t notice.

But if you have, this is sort of a pedestrian example, but say you have a roommate or a spouse who doesn’t clean up the kitchen. Facing that problem and not having your elegant solution already there to highlight the contrast between the perceived problem and the real problem, how would you take a problem like that and attack it using this method so that you can see what some of the other options might be?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right. So, I mean, let’s say it’s you who have that problem. I would go in and say, first of all, what would you say the problem is? Like, if you were to describe your view of the problem, what would that be?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I hate cleaning the kitchen, and I want someone else to clean it up.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: OK. So, my first observation, you know, that somebody else might not necessarily be your spouse. So, already there, there’s an inbuilt assumption in your question around oh, it has to be my husband who does the cleaning. So, it might actually be worth, already there to say, is that really the only problem you have? That you hate cleaning the kitchen, and you want to avoid it? Or might there be something around, as well, getting a better relationship in terms of how you solve problems in general or establishing a better way to handle small problems when dealing with your spouse?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Or maybe, now that I’m thinking that, maybe the problem is that you just can’t find the stuff in the kitchen when you need to find it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right, and so that’s an example of a reframing, that actually why is it a problem that the kitchen is not clean? Is it only because you hate the act of cleaning, or does it actually mean that it just takes you a lot longer and gets a lot messier to actually use the kitchen, which is a different problem. The way you describe this problem now, is there anything that’s missing from that description?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That is a really good question.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Other, basically asking other factors that we are not talking about right now, and I say those because people tend to, when given a problem, they tend to delve deeper into the detail. What often is missing is actually an element outside of the initial description of the problem that might be really relevant to what’s going on. Like, why does the kitchen get messy in the first place? Is it something about the way you use it or your cooking habits? Is it because the neighbor’s kids, kind of, use it all the time?

There might, very often, there might be issues that you’re not really thinking about when you first describe the problem that actually has a big effect on it.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I think at this point it would be helpful to maybe get another business example, and I’m wondering if you could tell us the story of the dog adoption problem.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Yeah. This is a big problem in the US. If you work in the shelter industry, basically because dogs are so popular, more than 3 million dogs every year enter a shelter, and currently only about half of those actually find a new home and get adopted. And so, this is a problem that has persisted. It’s been, like, a structural problem for decades in this space. In the last three years, where people found new ways to address it.

So a woman called Lori Weise who runs a rescue organization in South LA, and she actually went in and challenged the very idea of what we were trying to do. She said, no, no. The problem we’re trying to solve is not about how to get more people to adopt dogs. It is about keeping the dogs with their first family so they never enter the shelter system in the first place.

In 2013, she started what’s called a Shelter Intervention Program that basically works like this. If a family comes and wants to hand over their dog, these are called owner surrenders. It’s about 30% of all dogs that come into a shelter. All they would do is go up and ask, if you could, would you like to keep your animal? And if they said yes, they would try to fix whatever helped them fix the problem, but that made them turn over this.

And sometimes that might be that they moved into a new building. The landlord required a deposit, and they simply didn’t have the money to put down a deposit. Or the dog might need a $10 rabies shot, but they didn’t know how to get access to a vet.

And so, by instigating that program, just in the first year, she took her, basically the amount of dollars they spent per animal they helped went from something like $85 down to around $60. Just an immediate impact, and her program now is being rolled out, is being supported by the ASPCA, which is one of the big animal welfare stations, and it’s being rolled out to various other places.

And I think what really struck me with that example was this was not dependent on having the internet. This was not, oh, we needed to have everybody mobile before we could come up with this. This, conceivably, we could have done 20 years ago. Only, it only happened when somebody, like in this case Lori, went in and actually rethought what the problem they were trying to solve was in the first place.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, what I also think is so interesting about that example is that when you talk about it, it doesn’t sound like the kind of thing that would have been thought of through other kinds of problem solving methods. There wasn’t necessarily an After Action Review or a 5 Whys exercise or a Six Sigma type intervention. I don’t want to throw those other methods under the bus, but how can you get such powerful results with such a very simple way of thinking about something?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That was something that struck me as well. This, in a way, reframing and the idea of the problem diagnosis is important is something we’ve known for a long, long time. And we’ve actually have built some tools to help out. If you worked with us professionally, you are familiar with, like, Six Sigma, TRIZ, and so on. You mentioned 5 Whys. A root cause analysis is another one that a lot of people are familiar with.

Those are our good tools, and they’re definitely better than nothing. But what I notice when I work with the companies applying those was those tools tend to make you dig deeper into the first understanding of the problem we have. If it’s the elevator example, people start asking, well, is that the cable strength, or is the capacity of the elevator? That they kind of get caught by the details.

That, in a way, is a bad way to work on problems because it really assumes that there’s like a, you can almost hear it, a root cause. That you have to dig down and find the one true problem, and everything else was just symptoms. That’s a bad way to think about problems because problems tend to be multicausal.

There tend to be lots of causes or levers you can potentially press to address a problem. And if you think there’s only one, if that’s the right problem, that’s actually a dangerous way. And so I think that’s why, that this is a method I’ve worked with over the last five years, trying to basically refine how to make people better at this, and the key tends to be this thing about shifting out and saying, is there a totally different way of thinking about the problem versus getting too caught up in the mechanistic details of what happens.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: What about experimentation? Because that’s another method that’s become really popular with the rise of Lean Startup and lots of other innovation methodologies. Why wouldn’t it have worked to, say, experiment with many different types of fixing the dog adoption problem, and then just pick the one that works the best?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: You could say in the dog space, that’s what’s been going on. I mean, there is, in this industry and a lot of, it’s largely volunteer driven. People have experimented, and they found different ways of trying to cope. And that has definitely made the problem better. So, I wouldn’t say that experimentation is bad, quite the contrary. Rapid prototyping, quickly putting something out into the world and learning from it, that’s a fantastic way to learn more and to move forward.

My point is, though, that I feel we’ve come to rely too much on that. There’s like, if you look at the start up space, the wisdom is now just to put something quickly into the market, and then if it doesn’t work, pivot and just do more stuff. What reframing really is, I think of it as the cognitive counterpoint to prototyping. So, this is really a way of seeing very quickly, like not just working on the solution, but also working on our understanding of the problem and trying to see is there a different way to think about that.

If you only stick with experimentation, again, you tend to sometimes stay too much in the same space trying minute variations of something instead of taking a step back and saying, wait a minute. What is this telling us about what the real issue is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, to go back to something that we touched on earlier, when we were talking about the completely hypothetical example of a spouse who does not clean the kitchen–

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Completely, completely hypothetical.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Yes. For the record, my husband is a great kitchen cleaner.

You started asking me some questions that I could see immediately were helping me rethink that problem. Is that kind of the key, just having a checklist of questions to ask yourself? How do you really start to put this into practice?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I think there are two steps in that. The first one is just to make yourself better at the method. Yes, you should kind of work with a checklist. In the article, I kind of outlined seven practices that you can use to do this.

But importantly, I would say you have to consider that as, basically, a set of training wheels. I think there’s a big, big danger in getting caught in a checklist. This is something I work with.

My co-author Paddy Miller, it’s one of his insights. That if you start giving people a checklist for things like this, they start following it. And that’s actually a problem, because what you really want them to do is start challenging their thinking.

So the way to handle this is to get some practice using it. Do use the checklist initially, but then try to step away from it and try to see if you can organically make– it’s almost a habit of mind. When you run into a colleague in the hallway and she has a problem and you have five minutes, like, delving in and just starting asking some of those questions and using your intuition to say, wait, how is she talking about this problem? And is there a question or two I can ask her about the problem that can help her rethink it?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Well, that is also just a very different approach, because I think in that situation, most of us can’t go 30 seconds without jumping in and offering solutions.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Very true. The drive toward solutions is very strong. And to be clear, I mean, there’s nothing wrong with that if the solutions work. So, many problems are just solved by oh, you know, oh, here’s the way to do that. Great.

But this is really a powerful method for those problems where either it’s something we’ve been banging our heads against tons of times without making progress, or when you need to come up with a really creative solution. When you’re facing a competitor with a much bigger budget, and you know, if you solve the same problem later, you’re not going to win. So, that basic idea of taking that approach to problems can often help you move forward in a different way than just like, oh, I have a solution.

I would say there’s also, there’s some interesting psychological stuff going on, right? Where you may have tried this, but if somebody tries to serve up a solution to a problem I have, I’m often resistant towards them. Kind if like, no, no, no, no, no, no. That solution is not going to work in my world. Whereas if you get them to discuss and analyze what the problem really is, you might actually dig something up.

Let’s go back to the kitchen example. One powerful question is just to say, what’s your own part in creating this problem? It’s very often, like, people, they describe problems as if it’s something that’s inflicted upon them from the external world, and they are innocent bystanders in that.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Right, or crazy customers with unreasonable demands.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Exactly, right. I don’t think I’ve ever met an agency or consultancy that didn’t, like, gossip about their customers. Oh, my god, they’re horrible. That, you know, classic thing, why don’t they want to take more risk? Well, risk is bad.

It’s their business that’s on the line, not the consultancy’s, right? So, absolutely, that’s one of the things when you step into a different mindset and kind of, wait. Oh yeah, maybe I actually am part of creating this problem in a sense, as well. That tends to open some new doors for you to move forward, in a way, with stuff that you may have been struggling with for years.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, we’ve surfaced a couple of questions that are useful. I’m curious to know, what are some of the other questions that you find yourself asking in these situations, given that you have made this sort of mental habit that you do? What are the questions that people seem to find really useful?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: One easy one is just to ask if there are any positive exceptions to the problem. So, was there day where your kitchen was actually spotlessly clean? And then asking, what was different about that day? Like, what happened there that didn’t happen the other days? That can very often point people towards a factor that they hadn’t considered previously.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: We got take-out.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: S,o that is your solution. Take-out from [INAUDIBLE]. That might have other problems.

Another good question, and this is a little bit more high level. It’s actually more making an observation about labeling how that person thinks about the problem. And what I mean with that is, we have problem categories in our head. So, if I say, let’s say that you describe a problem to me and say, well, we have a really great product and are, it’s much better than our previous product, but people aren’t buying it. I think we need to put more marketing dollars into this.

Now you can go in and say, that’s interesting. This sounds like you’re thinking of this as a communications problem. Is there a different way of thinking about that? Because you can almost tell how, when the second you say communications, there are some ideas about how do you solve a communications problem. Typically with more communication.

And what you might do is go in and suggest, well, have you considered that it might be, say, an incentive problem? Are there incentives on behalf of the purchasing manager at your clients that are obstructing you? Might there be incentive issues with your own sales force that makes them want to sell the old product instead of the new one?

So literally, just identifying what type of problem does this person think about, and is there different potential way of thinking about it? Might it be an emotional problem, a timing problem, an expectations management problem? Thinking about what label of what type of problem that person is kind of thinking as it of.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That’s really interesting, too, because I think so many of us get requests for advice that we’re really not qualified to give. So, maybe the next time that happens, instead of muddying my way through, I will just ask some of those questions that we talked about instead.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That sounds like a good idea.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, Thomas, this has really helped me reframe the way I think about a couple of problems in my own life, and I’m just wondering. I know you do this professionally, but is there a problem in your life that thinking this way has helped you solve?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I’ve, of course, I’ve been swallowing my own medicine on this, too, and I think I have, well, maybe two different examples, and in one case somebody else did the reframing for me. But in one case, when I was younger, I often kind of struggled a little bit. I mean, this is my teenage years, kind of hanging out with my parents. I thought they were pretty annoying people. That’s not really fair, because they’re quite wonderful, but that’s what life is when you’re a teenager.

And one of the things that struck me, suddenly, and this was kind of the positive exception was, there was actually an evening where we really had a good time, and there wasn’t a conflict. And the core thing was, I wasn’t just seeing them in their old house where I grew up. It was, actually, we were at a restaurant. And it suddenly struck me that so much of the sometimes, kind of, a little bit, you love them but they’re annoying kind of dynamic, is tied to the place, is tied to the setting you are in.

And of course, if– you know, I live abroad now, if I visit my parents and I stay in my old bedroom, you know, my mother comes in and wants to wake me up in the morning. Stuff like that, right? And it just struck me so, so clearly that it’s– when I change this setting, if I go out and have dinner with them at a different place, that the dynamic, just that dynamic disappears.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Well, Thomas, this has been really, really helpful. Thank you for talking with me today.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Thank you, Sarah.

HANNAH BATES: That was Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg in conversation with Sarah Green Carmichael on the HBR IdeaCast. He’s an expert in problem solving and innovation, and he’s the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

We’ll be back next Wednesday with another hand-picked conversation about leadership from the Harvard Business Review. If you found this episode helpful, share it with your friends and colleagues, and follow our show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. While you’re there, be sure to leave us a review.

We’re a production of Harvard Business Review. If you want more podcasts, articles, case studies, books, and videos like this, find it all at HBR dot org.

This episode was produced by Anne Saini, and me, Hannah Bates. Ian Fox is our editor. Music by Coma Media. Special thanks to Maureen Hoch, Adi Ignatius, Karen Player, Ramsey Khabbaz, Nicole Smith, Anne Bartholomew, and you – our listener.

See you next week.

- Subscribe On:

Latest in this series

This article is about leadership.

- Decision making and problem solving

- Power and influence

- Business management

Partner Center

Worawut/Adobe Stock

By Jill Babcock Leaders Staff

Jill Babcock

Personal Development Writer

Jillian Babcock is a personal development writer for Leaders Media. Previously, she was a senior content writer at Ancient Nutrition,...

Learn about our editorial policy

Aug 8, 2023

Reviewed by Hannah L. Miller

Hannah L. Miller

Senior Editor

Hannah L. Miller, MA, is the senior editor for Leaders Media. Since graduating with her Master of Arts in 2015,...

The Power of the Five Whys: Drilling Down to Effectively Problem-Solve

What is the “5 whys” method, the power of asking “why”, when the 5 whys should be used, how to utilize the 5 whys technique, five whys examples, other ways of improving problem-solving.

It’s a fact of life that things don’t always go according to plan. When facing mistakes or challenges, asking “why”—especially if you do it repeatedly—can help uncover deeper layers of understanding so you can identify potential solutions.

The question “why” can be used in problem-solving as a powerful technique that helps us dig deeper, challenge assumptions, and think critically. After all, if you’re not sure why a problem exists in the first place, it’s very difficult to solve it.

The “Five Whys” method (also called “5 Whys Root Cause Analysis”) can specifically help in examining beliefs, behaviors, and patterns to shine a light on areas for improvement. The Five Whys have other benefits too, including encouraging collaboration and communication since this strategy promotes open dialogue among team members or partners. It also helps generate effective and lasting solutions that can prevent similar issues from resurfacing in the future.

In this article, learn how to use the Five Whys to save yourself or your company from wasting time and money and to address important issues at their source before they escalate.

The “Five Whys” is a technique commonly used in problem-solving to find the root causes of problems . This type of analysis can be applied to various situations, including within companies and relationships, to gain deeper insights and understandings of challenges and obstacles. The method involves “drilling down” by repeatedly asking “why”—typically five times or more—to get to the underlying causes or motivations behind a particular issue. Overall, it’s a way to figure out causes and effects related to a situation so that solutions can be uncovered.

“Effective problem solving can help organizations improve in every area of their business, including product quality, client satisfaction, and finances.” Jamie Birt , Career Coach

Here are a few reasons why asking “why,” or practicing the Five Whys, is important in problem-solving:

- Identifies underlying issues and root causes: Repeatedly asking “why” helps peel back the layers of a problem to get closer to the heart of what’s not working well. The goal is to define the real issue at hand to address its underlying causes. Understanding root causes is crucial because it enables you to address issues at their source rather than simply dealing with surface-level effects.

- Promotes critical thinking: Critical thinking refers to the process of objectively and analytically evaluating information, arguments, or situations. To engage in critical thinking and analysis, we need to ask “why,” usually over and over again. This encourages us to develop a more nuanced understanding of a problem by evaluating different factors, examining relationships, and considering different perspectives. Doing so helps lead to well-reasoned judgments and informed decisions.

- Uncovers assumptions: The opposite of assuming something is remaining open-minded and curious about it. Albert Einstein once said , “The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.” Asking “why” prompts you to challenge preconceived notions you may not even realize you have. Often, we make assumptions about a problem or its causes without having all the information we need. By gaining a fresh perspective, we can consider alternative solutions.

- Generates insights: The Five Whys can lead to valuable discoveries and potential fixes by uncovering hidden connections. These insights can guide us toward innovative solutions that prevent similar problems from worsening or happening again.

“Curiosity has been identified as a characteristic of high-performing salespeople, and having a tool and system that fosters curiosity in your team is extremely helpful.” Alexander Young, Forbes

Any time a problem needs to be clarified and solved, the Five Whys can help. This flexible technique can be adapted to different situations, including personal and professional ones. For example, it’s useful when there are complications within businesses that are causing a loss of profits or when arguments occur among family members or partners. Eric Ries from Harvard Business Review points out that start-ups can especially benefit from the Five Whys to test and refine procedures, ideas, products, and processes.

To get the most out of the Five Whys, include people with personal knowledge of the problem, processes, and systems involved in the analysis, such as employees and customers. This means that if a leadership team, for example, wants to use the Five Whys to improve customer engagement, actual customers and customer service representatives would be ideal people to include in the discussion.

Here are examples of situations in which the Five Whys can be utilized:

- Troubleshooting business processes or operations issues, such as delivery or customer service concerns.

- Identifying the reasons behind personal challenges or recurring problems, such as disputes between bosses and employees.

- Analyzing project failures or setbacks, such as missed deadlines, to find underlying causes.

- Understanding customer complaints or dissatisfaction to improve products or services.

- Improving communication, teamwork, and client relationships.

Sakichi Toyoda (1867–1930) was a Japanese inventor and industrialist known for his business ventures, including founding the Toyota Motor Corporation. Toyoda is credited with developing the Five Whys method in the 1930s, which he used to support continuous improvement within his companies .

For example, within Toyota Production System (TPS), key goals included eliminating waste, improving efficiency, and ensuring quality. Toyoda used the Five Whys to identify problems within his company and to find ways to resolve them to improve production and customer satisfaction. He once stated , “By repeating why five times, the nature of the problem as well as its solution becomes clear.”

“The beauty of the [Five Whys] tool is in its simplicity. Not only is it universally applicable, it also ensures that you don’t move to action straight away without fully considering whether the reason you’ve identified really is the cause of the problem.” Think Design

The Five Whys works by drilling down to a main underlying cause. The answer to the first “why” should prompt another “why,” and then the answer to the second “why” should continue to prompt more “whys” until a root cause is identified.

Follow these steps to implement the Five Whys:

1. Identify the Initial Problem: Clearly define the problem you want to address. Be specific, such as by including details that help with the analysis. Make sure to clearly articulate the issue by breaking it down into smaller components to ensure everyone involved has a thorough understanding of the situation.

2. Ask “Why?”: Start by asking why the problem occurred. Answer your own question. The answer becomes the basis for the next “why” question.

3. Repeat the Process Five or More Times: Continue asking “why” about the previous answer, iterating at least five times or until you reach a point where the root cause of the problem becomes apparent.

4. Analyze and Take Action: Once you have identified the root cause, analyze potential solutions and take appropriate action.

Here’s a template that you can use to make the process simple:

Problem Statement: (One sentence description of the main problem)

- Why is the problem happening? (Insert answer)

- Why is the answer above happening? (Insert answer)

Root Cause(s)

To test if the root cause is correct, ask yourself the following: “If you removed this root cause, would this problem be resolved?”

Potential Solutions:

List one or more ways you can resolve the root cause of the problem.

The Five Whys method is not a rigid rule but rather a flexible framework that can be adjusted based on the complexity of the problem. You may need to ask “why” only three times or more than five times, such as 7 to 9 times, to nail down the main underlying cause. It’s not the exact amount of “whys” you ask that matters, more so that you’re really investigating the situation and getting to the root of the issue.

Here are two examples of how the Five Whys technique can be used to problem-solve:

Example 1: Machine Breakdown

- Problem Statement: A machine in a manufacturing facility keeps breaking down.

- Why did the machine break down? The motor overheated.

- Why did the motor overheat? The cooling system failed.

- Why did the cooling system fail? The coolant pump malfunctioned.

- Why did the coolant pump malfunction? It wasn’t properly maintained.

- Why wasn’t the coolant pump properly maintained? There was no regular maintenance schedule in place.

- Root Cause: The lack of a regular maintenance schedule led to the coolant pump malfunction and subsequent machine breakdown.

- Solution: Implement a scheduled maintenance program for all machines to ensure proper upkeep and prevent breakdowns.

Example 2: Orders Not Being Fulfilled On Time

- Problem Statement: The order fulfillment process in an e-commerce company is experiencing delays.

- Why are there delays in the order fulfillment process? The warehouse staff is spending excessive time searching for products.

- Why are they spending excessive time searching for products? The products are not organized efficiently in the warehouse.

- Why are the products not organized efficiently? There is no standardized labeling system for product placement.

- Why is there no standardized labeling system? The inventory management software does not support it.

- Why doesn’t the inventory management software support a labeling system? The current software version is outdated and lacks the necessary features.

- Root Cause: The use of outdated inventory management software lacking labeling functionality leads to inefficient product organization and delays in the order fulfillment process.

- Solution: Upgrade the inventory management software to a newer version that supports a standardized labeling system, improving product organization and streamlining the order fulfillment process.

“Great leaders are, at their core, great problem-solvers. They take proactive measures to avoid conflicts and address issues when they arise.” Alison Griswold , Business and Economics Writer

Problem-solving is a skill that can be developed and improved over time. The Five Whys method is most effective when used in conjunction with other problem-solving tools and when utilized in a collaborative environment that encourages open communication and a willingness to honestly explore underlying causes. For the method to work well, “radical candor” needs to be utilized, and constructive feedback needs to be accepted.

Here are other strategies to assist in problem-solving, most of which can be used alongside the Five Whys:

- Gather and analyze information: Collect relevant data, facts, and information related to the problem. This could involve conducting research, talking to experts, or analyzing past experiences. Examine the information you’ve gathered and identify patterns, connections, and potential causes of the problem. Look for underlying factors and consider both the immediate and long-term implications.

- Have a brainstorming session: Collaborate with colleagues, seek advice from experts, or gather input from stakeholders. Different perspectives can bring fresh ideas. Gather a group of teammates and get out a whiteboard and a marker. Create a list of opportunities or problems and potential solutions. Encourage creativity and think outside the box. Consider different perspectives and approaches.

- Draw a cause-and-effect diagram: Make a chart with three columns, one each for challenges, causes, and effects. Use this to come up with solutions, then assess the pros and cons of each potential solution by considering the feasibility, potential risks, and benefits associated with each option.

- Develop an action plan: Once you’ve selected the best solution(s), create a detailed action plan. Define the steps required to implement the solution, set timelines, and then track your progress.

Want to learn more about problem-solving using critical thinking? Check out this article:

Use Critical Thinking Skills to Excel at Problem-Solving

Leaders Media has established sourcing guidelines and relies on relevant, and credible sources for the data, facts, and expert insights and analysis we reference. You can learn more about our mission, ethics, and how we cite sources in our editorial policy .

- American Institute of Physics. Albert Einstein Image and Impact . History Exhibit. https://history.aip.org/exhibits/einstein/ae77.htm

- Indeed. 5 Whys Example: A Powerful Problem-Solving Tool for Career Development. Indeed Career Guide. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/5-whys-example

- Entrepreneur. 3 Steps to Creating a Culture of Problem Solvers . Entrepreneur – Leadership. https://www.entrepreneur.com/leadership/3-steps-to-creating-a-culture-of-problem-solvers/436071

- Harvard Business Review. (2010, April). The Five Whys for Startups. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/04/the-five-whys-for-startups

- Forbes. (2021, June 7). Understanding The Five Whys: How To Successfully Integrate This Tool Into Your Business . Forbes – Entrepreneurs. https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2021/06/07/understanding-the-five-whys-how-to-successfully-integrate-this-tool-into-your-business/?sh=5eda43675c18

- Think Design. Five Whys: Get to the Root of Any Problem Quickly. Think Design – User Design Research. https://think.design/user-design-research/five-whys

- Business Insider. (2013, November). The Problem-Solving Tactics of Great Leaders. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/problem-solving-tactics-of-great-leaders-2013-11

Search Leaders.com

- Career Advice

- Job Search & Interview

- Productivity

- Public Speaking and Presentation

- Social & Interpersonal Skills

- Professional Development

- Remote Work

- Our Products

Eggcellent Work

Importance of problem solving skills in leadership – make a difference and be successful.

Great leaders in U.S. history showed how you can make a difference and be successful. They are exemplars of the importance of problem solving skills in leadership:

- George Washington led a ragtag army of colonial soldiers against the professional army of a world power. He overcame almost insurmountable problems as a military leader and as the first president of a new republic.

- Abraham Lincoln was the president of a country coming apart at the seams. His determined leadership and overcoming problems, during a time when others gave up, preserved our republic through an unprecedented crisis.

- Franklin D. Ro osevelt assumed office during the nation’s Great Depression. His administration was focused on solutions with the goal of restoring hope and confidence during a time of hardship and economic crisis.

- Martin Luther King attacked the problems of racial discrimination and prejudice with fearless resolve and unparalleled leadership. His “I have a dream” speech is a classic call to solve lingering problems of unfulfilled promises of the American dream.

Table of Contents

How Recruiters Identify the Best Potential Leadership and Problem Solvers

The career path to the C-suite is paved by organizations that increasingly seek solid leadership skills when adding talent to their workforce.

According to Stephany Samuels , a senior vice president at an IT recruiting and staffing firm, “Companies thrive and grow when their workforce is comprised of leaders that instinctively explore creative solutions and bring out the best in their colleagues.”

What are the leadership traits and qualities recruiters should be looking for? According to this CNBC article , problem-solving ranks in the top three. Employers want to recruit talented people, “who are quick on their feet and comfortable resolving conflicts with unique solutions.”

- Critical Thinking vs Problem Solving: What’s the Difference?

- Top 12 Soft Skills Consulting Firms Look For

Why Problem Solving Skills are a Vital Ingredient in Your Leadership Tool Bag

Duke Ellington once observed that “A problem is a chance for you to do your best.” If you leverage your problem-solving skills, you can encourage the best performance from your team.

Effective leaders are high-level thinkers and students of human behavior. They find answers to difficult questions because their approach is rooted in strong problem-solving skills. Your own workplace problems can result from conflict, competition for resources, or poor communication. You can harness that energy with dynamic problem-solving skills.

By adapting problem-led leadership styles to your work culture, you can identify and proactively solve complex problems in the leadership challenges of your business. You can excite your team and bring unity in the organization. That unity and team spirit taps into everyone’s expertise to solve problems.

Types of leadership problems and their solutions

As a leader, you will face several types of problems. Some examples are problems that:

- were never faced before: e.g., the recent pandemic and new challenges faced by remote workers—productivity, network security, etc.

- require multiple solutions to sometimes conflicting goals: e.g., a need to cut costs without having to lay off any employees.

- are complex: e.g., a solution involving a large number of known or unknown factors—stake holders who have conflicting agendas and questionable loyalty to the entire organization.

- are dynamic: e.g., a problem with a non-negotiable deadline for solving it

Problem solving can be learned through techniques that involve:

- looking at the elements of the problem and understanding the dynamics affecting the situation

- understanding the causes behind the problem

- knowing how to leverage your advantage as well as understanding what difficulties you are facing

- evaluating the strengths of your team and their ability to help in solving the problem

Read More: Life Of A Leader: What A Leader Does Everyday To Be Successful

How Leaders Solve Problems

Albert Einstein once said this about problem solving: “We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them.” You cannot expect problems to go away on their own. Problem solving requires creative and proactive solutions and skills.

You can hone problem-solving skills with the sharp edges of a positive outlook. That approach is the opposite of the energy-draining commitment to unproductive struggle, which reinforces inertia.

When blame and repercussions and saying “oh, no!” poison your team, the classic movie Apollo 13 line “Houston, we have a problem” could be “Oh, no! Houston, we’re gonna die up here!”

In Apollo 13, the ground crew found solutions with only the material at hand. You can emulate that approach by saying “yes” to problems. Do that and you will employ, promote, and encourage an approach that focuses on strengths and opportunities. That approach includes:

1. Identifying the problem : Spend extra time defining problems and avoiding premature, inadequate solutions. The governing philosophy here is “A problem well stated is half solved.”

2. Evaluating the problem: You can get to the root cause of a problem by:

- looking for common patterns

- asking questions—what? who? where? when? and how?

- avoiding assigning blame and engaging in negativity

- seeking knowledge of every aspect of the issue in order to move forward

3. Backing up proposed solutions with data : By using data already accumulated over time, you can bring a persistent problem into perspective. Data analysis often connects the dots and leads to discoveries through common patterns.

4. Practicing honest communication and transparency. When you have a clear plan of action to resolve a problem, you can avoid the appearance of having a hidden agenda. The road to trust, respect and confidence from your team is through transparency. Transparency will keep the team invested and motivated in solving the problem.