ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Climate change.

Climate change is a long-term shift in global or regional climate patterns. Often climate change refers specifically to the rise in global temperatures from the mid-20th century to present.

Earth Science, Climatology

Fracking tower

Fracking is a controversial form of drilling that uses high-pressure liquid to create cracks in underground shale to extract natural gas and petroleum. Carbon emissions from fossils fuels like these have been linked to global warming and climate change.

Photograph by Mark Thiessen / National Geographic

Climate is sometimes mistaken for weather. But climate is different from weather because it is measured over a long period of time, whereas weather can change from day to day, or from year to year. The climate of an area includes seasonal temperature and rainfall averages, and wind patterns. Different places have different climates. A desert, for example, is referred to as an arid climate because little water falls, as rain or snow, during the year. Other types of climate include tropical climates, which are hot and humid , and temperate climates, which have warm summers and cooler winters.

Climate change is the long-term alteration of temperature and typical weather patterns in a place. Climate change could refer to a particular location or the planet as a whole. Climate change may cause weather patterns to be less predictable. These unexpected weather patterns can make it difficult to maintain and grow crops in regions that rely on farming because expected temperature and rainfall levels can no longer be relied on. Climate change has also been connected with other damaging weather events such as more frequent and more intense hurricanes, floods, downpours, and winter storms.

In polar regions, the warming global temperatures associated with climate change have meant ice sheets and glaciers are melting at an accelerated rate from season to season. This contributes to sea levels rising in different regions of the planet. Together with expanding ocean waters due to rising temperatures, the resulting rise in sea level has begun to damage coastlines as a result of increased flooding and erosion.

The cause of current climate change is largely human activity, like burning fossil fuels , like natural gas, oil, and coal. Burning these materials releases what are called greenhouse gases into Earth’s atmosphere . There, these gases trap heat from the sun’s rays inside the atmosphere causing Earth’s average temperature to rise. This rise in the planet's temperature is called global warming. The warming of the planet impacts local and regional climates. Throughout Earth's history, climate has continually changed. When occuring naturally, this is a slow process that has taken place over hundreds and thousands of years. The human influenced climate change that is happening now is occuring at a much faster rate.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- ENVIRONMENT

How global warming is disrupting life on Earth

The signs of global warming are everywhere, and are more complex than just climbing temperatures.

Our planet is getting hotter. Since the Industrial Revolution—an event that spurred the use of fossil fuels in everything from power plants to transportation—Earth has warmed by 1 degree Celsius, about 2 degrees Fahrenheit.

That may sound insignificant, but 2023 was the hottest year on record , and all 10 of the hottest years on record have occurred in the past decade.

Global warming and climate change are often used interchangeably as synonyms, but scientists prefer to use “climate change” when describing the complex shifts now affecting our planet’s weather and climate systems.

Climate change encompasses not only rising average temperatures but also natural disasters, shifting wildlife habitats, rising seas , and a range of other impacts. All of these changes are emerging as humans continue to add heat-trapping greenhouse gases , like carbon dioxide and methane, to the atmosphere.

What causes global warming?

When fossil fuel emissions are pumped into the atmosphere, they change the chemistry of our atmosphere, allowing sunlight to reach the Earth but preventing heat from being released into space. This keeps Earth warm, like a greenhouse, and this warming is known as the greenhouse effect .

Carbon dioxide is the most commonly found greenhouse gas and about 75 percent of all the climate warming pollution in the atmosphere. This gas is a product of producing and burning oil, gas, and coal. About a quarter of Carbon dioxide also results from land cleared for timber or agriculture.

Methane is another common greenhouse gas. Although it makes up only about 16 percent of emissions, it's roughly 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide and dissipates more quickly. That means methane can cause a large spark in warming, but ending methane pollution can also quickly limit the amount of atmospheric warming. Sources of this gas include agriculture (mostly livestock), leaks from oil and gas production, and waste from landfills.

What are the effects of global warming?

One of the most concerning impacts of global warming is the effect warmer temperatures will have on Earth's polar regions and mountain glaciers. The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the planet. This warming reduces critical ice habitat and it disrupts the flow of the jet stream, creating more unpredictable weather patterns around the globe.

( Learn more about the jet stream. )

A warmer planet doesn't just raise temperatures. Precipitation is becoming more extreme as the planet heats. For every degree your thermometer rises, the air holds about seven percent more moisture. This increase in moisture in the atmosphere can produce flash floods, more destructive hurricanes, and even paradoxically, stronger snow storms.

The world's leading scientists regularly gather to review the latest research on how the planet is changing. The results of this review is synthesized in regularly published reports known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports.

A recent report outlines how disruptive a global rise in temperature can be:

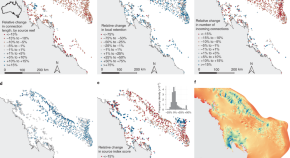

- Coral reefs are now a highly endangered ecosystem. When corals face environmental stress, such as high heat, they expel their colorful algae and turn a ghostly white, an effect known as coral bleaching . In this weakened state, they more easily die.

- Trees are increasingly dying from drought , and this mass mortality is reshaping forest ecosystems.

- Rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns are making wildfires more common and more widespread. Research shows they're even moving into the eastern U.S. where fires have historically been less common.

- Hurricanes are growing more destructive and dumping more rain, an effect that will result in more damage. Some scientists say we even need to be preparing for Cat 6 storms . (The current ranking system ends at Cat 5.)

How can we limit global warming?

Limiting the rising in global warming is theoretically achievable, but politically, socially, and economically difficult.

Those same sources of greenhouse gas emissions must be limited to reduce warming. For example, oil and gas used to generate electricity or power industrial manufacturing will need to be replaced by net zero emission technology like wind and solar power. Transportation, another major source of emissions, will need to integrate more electric vehicles, public transportation, and innovative urban design, such as safe bike lanes and walkable cities.

( Learn more about solutions to limit global warming. )

One global warming solution that was once considered far fetched is now being taken more seriously: geoengineering. This type of technology relies on manipulating the Earth's atmosphere to physically block the warming rays of the sun or by sucking carbon dioxide straight out of the sky.

Restoring nature may also help limit warming. Trees, oceans, wetlands, and other ecosystems help absorb excess carbon—but when they're lost, so too is their potential to fight climate change.

Ultimately, we'll need to adapt to warming temperatures, building homes to withstand sea level rise for example, or more efficiently cooling homes during heat waves.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- CLIMATE CHANGE

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

- POLAR REGIONS

You May Also Like

Why all life on Earth depends on trees

Life probably exists beyond Earth. So how do we find it?

For Antarctica’s emperor penguins, ‘there is no time left’

Polar bears are trying to adapt to a warming Arctic. It’s not working.

A photographic eulogy for Greenland's departing icebergs

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Science News

Abdulhamid Hosbas/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Century of Science: Theme

Our climate change crisis

The climate change emergency.

Even in a world increasingly battered by weather extremes, the summer 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest stood out. For several days in late June, cities such as Vancouver, Portland and Seattle baked in record temperatures that killed hundreds of people. On June 29 Lytton, a village in British Columbia, set an all-time heat record for Canada, at 121° Fahrenheit (49.6° Celsius); the next day, the village was incinerated by a wildfire.

Within a week, an international group of scientists had analyzed this extreme heat and concluded it would have been virtually impossible without climate change caused by humans. The planet’s average surface temperature has risen by at least 1.1 degree Celsius since preindustrial levels of 1850–1900 — because people are loading the atmosphere with heat-trapping gases produced during the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal and gas, and from cutting down forests.

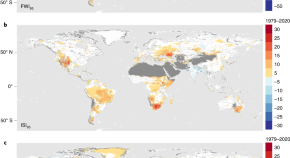

A little over 1 degree of warming may not sound like a lot. But it has already been enough to fundamentally transform how energy flows around the planet. The pace of change is accelerating, and the consequences are everywhere. Ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are melting, raising sea levels and flooding low-lying island nations and coastal cities. Drought is parching farmlands and the rivers that feed them. Wildfires are raging. Rains are becoming more intense, and weather patterns are shifting .

The roots of understanding this climate emergency trace back more than a century and a half. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that scientists began the detailed measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide that would prove how much carbon is pouring from human activities. Beginning in the 1960s, researchers began developing comprehensive computer models that now illuminate the severity of the changes ahead.

Global average temperature change, 1850–2021

Long-term climate datasets show that Earth’s average surface temperature (combined land and ocean) has increased by more than 1 degree Celsius since preindustrial times. Temperature change is the difference from the 1850–1900 average.

Today we know that climate change and its consequences are real, and we are responsible. The emissions that people have been putting into the air for centuries — the emissions that made long-distance travel, economic growth and our material lives possible — have put us squarely on a warming trajectory . Only drastic cuts in carbon emissions, backed by collective global will, can make a significant difference.

“What’s happening to the planet is not routine,” says Ralph Keeling, a geochemist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif. “We’re in a planetary crisis.” — Alexandra Witze

Tracking a Greenland glacier

The calving front of Greenland’s Helheim Glacier, which flows toward the sea where it crumbles into icebergs, held roughly the same position from the 1970s until 2001 (left, the calving front is to the far right of the image). But by 2005 (right), it had retreated 7.5 kilometers toward its source.

The first climate scientists

One day in the 1850s, Eunice Newton Foote, an amateur scientist and women’s rights activist living in upstate New York, put two glass jars in sunlight. One contained regular air — a mix of nitrogen, oxygen and other gases including carbon dioxide — while the other contained just CO 2 . Both had thermometers in them. As the sun’s rays beat down, Foote observed that the jar of CO 2 alone heated more quickly, and was slower to cool, than the one containing plain air.

The results prompted Foote to muse on the relationship between CO 2 , the planet and heat. “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature,” she wrote in an 1856 paper summarizing her findings .

Three years later, working independently and apparently unaware of Foote’s discovery, Irish physicist John Tyndall showed the same basic idea in more detail. With a set of pipes and devices to study the transmission of heat, he found that CO 2 gas, as well as water vapor, absorbed more heat than air alone. He argued that such gases would trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, much as panes of glass trap heat in a greenhouse, and thus modulate climate. “As a dam built across a river causes a local deepening of the stream, so our atmosphere, thrown as a barrier across the terrestrial rays, produces a local heightening of the temperature at the Earth’s surface,” he wrote in 1862.

Today Tyndall is widely credited with the discovery of how what are now called greenhouse gases heat the planet, earning him a prominent place in the history of climate science. Foote faded into relative obscurity — partly because of her gender, partly because her measurements were less sensitive. Yet their findings helped kick off broader scientific exploration of how the composition of gases in Earth’s atmosphere affects global temperatures.

Carbon floods in

Humans began substantially affecting the atmosphere around the turn of the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution took off in Britain. Factories burned tons of coal; fueled by fossil fuels, the steam engine revolutionized transportation and other industries. In the decades since, fossil fuels including oil and natural gas have been harnessed to drive a global economy. All these activities belch gases into the air.

Yet Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish physical chemist, wasn’t worried about the Industrial Revolution when he began thinking in the late 1800s about changes in atmospheric CO 2 levels. He was instead curious about ice ages — including whether a decrease in volcanic eruptions, which can put CO 2 into the atmosphere, would lead to a future ice age. Bored and lonely in the wake of a divorce, Arrhenius set himself to months of laborious calculations involving moisture and heat transport in the atmosphere at different zones of latitude. In 1896 he reported that halving the amount of CO 2 in the atmosphere could indeed bring about an ice age — and that doubling CO 2 would raise global temperatures by around 5 to 6 degrees C.

It was a remarkably prescient finding for work that, out of necessity, had simplified Earth’s complex climate system down to just a few variables. Today, estimates for how much the planet will warm through a doubling of CO 2 — a measure known as climate sensitivity — range between 1.5 degrees and 4.5 degrees Celsius. (The range remains broad in part because scientists now incorporate their understanding of many more planetary feedbacks than were recognized in Arrhenius’ day.)

But Arrhenius’ findings didn’t gain much traction with other scientists at the time. The climate system seemed too large, complex and inert to change in any meaningful way on a timescale that would be relevant to human society. Geologic evidence showed, for instance, that ice ages took thousands of years to start and end. What was there to worry about? And other laboratory experiments — later shown to be flawed — appeared to indicate that changing levels of CO 2 would have little impact on heat absorption in the atmosphere. Most scientists aware of the work came to believe that Arrhenius had been proved wrong.

One researcher, though, thought the idea was worth pursuing. Guy Stewart Callendar, a British engineer and amateur meteorologist, had tallied weather records over time, obsessively enough to determine that average temperatures were increasing at 147 weather stations around the globe. In 1938, in a paper in a Royal Meteorological Society journal , he linked this temperature rise to the burning of fossil fuels. Callendar estimated that fossil fuel burning had put around 150 billion metric tons of CO 2 into the atmosphere since the late 19th century.

Like many of his day, Callendar didn’t see global warming as a problem. Extra CO 2 would surely stimulate plants to grow and allow crops to be farmed in new regions. “In any case the return of the deadly glaciers should be delayed indefinitely,” he wrote. But his work revived discussions tracing back to Tyndall and Arrhenius about how the planetary system responds to changing levels of gases in the atmosphere. And it began steering the conversation toward how human activities might drive those changes.

When World War II broke out the following year, the global conflict redrew the landscape for scientific research. Hugely important wartime technologies, such as radar and the atomic bomb, set the stage for “big science” studies that brought nations together to tackle high-stakes questions of global reach. And that allowed modern climate science to emerge.

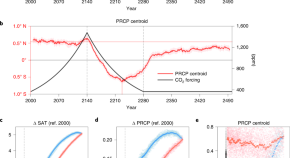

The Keeling curve and climate change

One major postwar effort was the International Geophysical Year, an 18-month push in 1957–1958 that involved a wide array of scientific field campaigns including exploration in the Arctic and Antarctica. Climate change wasn’t a high research priority during the IGY, but some scientists in California, led by Roger Revelle of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, used the funding influx to begin a project they’d long wanted to do. The goal was to measure CO 2 levels at different locations around the world, accurately and consistently.

The job fell to geochemist Charles David Keeling, who put ultraprecise CO 2 monitors in Antarctica and on the Hawaiian volcano of Mauna Loa. Funds soon ran out to maintain the Antarctic record, but the Mauna Loa measurements continued. Thus was born one of the most iconic datasets in all of science — the “Keeling curve,” which tracks the rise of atmospheric CO 2 . When Keeling began his measurements in 1958, CO 2 made up 315 parts per million of the global atmosphere. Within just a few years it became clear that the number was increasing year by year. Because plants take up CO 2 as they grow in spring and summer and release it as they decompose in fall and winter, CO 2 concentrations rose and fell each year in a sawtooth pattern — but superimposed on that pattern was a steady march upward.

Monthly average CO 2 concentrations at Mauna Loa Observatory

Atmospheric carbon dioxide measurements collected continuously since 1958 at Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii show the rise due to human activities. The visible sawtooth pattern is due to seasonal plant growth: Plants take up CO 2 in the growing seasons, then release it as they decompose in fall and winter.

“The graph got flashed all over the place — it was just such a striking image,” says Ralph Keeling, who is Charles David Keeling’s son. Over the years, as the curve marched higher, “it had a really important role historically in waking people up to the problem of climate change.” The Keeling curve has been featured in countless earth science textbooks, congressional hearings and in Al Gore’s 2006 documentary on climate change, An Inconvenient Truth . Each year the curve keeps going up: In 2016 it passed 400 ppm of CO 2 in the atmosphere, as measured during its typical annual minimum in September. In 2021, the annual minimum was 413 ppm. (Before the Industrial Revolution, CO 2 levels in the atmosphere had been stable for centuries at around 280 ppm.)

Around the time that Keeling’s measurements were kicking off, Revelle also helped develop an important argument that the CO 2 from human activities was building up in Earth’s atmosphere. In 1957 he and Hans Suess, also at Scripps at the time, published a paper that traced the flow of radioactive carbon through the oceans and the atmosphere. They showed that the oceans were not capable of taking up as much CO 2 as previously thought; the implication was that much of the gas must be going into the atmosphere instead. “Human beings are now carrying out a large-scale geophysical experiment of a kind that could not have happened in the past nor be reproduced in the future,” Revelle and Suess wrote in the paper. It’s one of the most famous sentences in earth science history.

“Human beings are now carrying out a large-scale geophysical experiment of a kind that could not have happened in the past nor be reproduced in the future.”

Here was the insight underlying modern climate science: Atmosheric CO 2 is increasing, and humans are causing the buildup. Revelle and Suess became the final piece in a puzzle dating back to Svante Arrhenius and John Tyndall.

“I tell my students that to understand the basics of climate change, you need to have the cutting-edge science of the 1860s, the cutting-edge math of the 1890s and the cutting-edge chemistry of the 1950s,” says Joshua Howe, an environmental historian at Reed College in Portland, Ore.

Environmental awareness grows

As this scientific picture began to emerge in the late 1950s, Science News was on the story. A March 1, 1958 article in Science News Letter , “Weather May Be Warming,” described a warm winter month in the Northern Hemisphere. It posits three theories, including that “carbon dioxide poured into the atmosphere by a booming industrial civilization could have caused the increase. By burning up about 100 billion tons of coal and oil since 1900, man himself may be changing the climate.” By 1972, the magazine was reporting on efforts to expand global atmospheric greenhouse gas monitoring beyond Keeling’s work; two years later, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration launched its own CO 2 monitoring network, now the biggest in the world.

Environmental awareness on other issues grew in the 1960s and 1970s. Rachel Carson catalyzed the modern U.S. environmental movement in 1962 when she published a magazine series and then a book, Silent Spring , condemning the pesticide DDT for its ecological impacts. 1970 saw the celebration of the first Earth Day , in the United States and elsewhere, and in India in 1973 a group of women led a series of widely publicized protests against deforestation. This Chipko movement explicitly linked environmental protection with protecting human communities, and helped seed other environmental movements.

The fragility of global energy supplies was also becoming more obvious through the 1970s. The United States, heavily dependent on other countries for oil imports, entered a gas shortage in 1973–74 when Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries cut off oil supplies because of U.S. government support for Israel. The shortage prompted more people to think about the finiteness of natural resources and the possibility of overtaxing the planet. — Alexandra Witze

Climate change evidence piles up

Observational data collected throughout the second half of the 20th century helped researchers gradually build their understanding of how human activities were transforming the planet. “It was a sort of slow accretion of evidence and concern,” says historian Joshua Howe of Reed College.

Environmental records from the past, such as tree rings and ice cores, established that the current changes in climate are unusual compared with the recent past. Yet such paleoclimatology data also showed that climate has changed quickly in the deep past — driven by triggers other than human activity, but with lessons for how abrupt planetary transformations can be.

Ice cores pulled from ice sheets, such as that atop Greenland, offer some of the most telling insights for understanding past climate change. Each year snow falls atop the ice and compresses into a fresh layer of ice representing climate conditions at the time it formed. The abundance of certain forms, or isotopes, of oxygen and hydrogen in the ice allows scientists to calculate the temperature at which it formed, and air bubbles trapped within the ice reveal how much carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases were in the atmosphere at that time. So drilling down into an ice sheet is like reading the pages of a history book that go back in time the deeper you go.

Scientists began reading these pages in the early 1960s, using ice cores drilled at a U.S. military base in northwest Greenland . Contrary to expectations that past climates were stable, the cores hinted that abrupt climate shifts had happened over the last 100,000 years. By 1979, an international group of researchers was pulling another deep ice core from a second location in Greenland — and it, too, showed that abrupt climate change had occurred in the past. In the late 1980s and early 1990s a pair of European- and U.S.-led drilling projects retrieved even deeper cores from near the top of the ice sheet, pushing the record of past temperatures back a quarter of a million years.

Together with other sources of information, such as sediment cores drilled from the seafloor and molecules preserved in ancient rocks, the ice cores allowed scientists to reconstruct past temperature changes in extraordinary detail. Many of those changes happened alarmingly fast. For instance, the climate in Greenland warmed abruptly more than 20 times in the last 80,000 years, with the changes occurring in a matter of decades. More recently, a cold spell that set in around 13,000 years ago suddenly came to an end around 11,500 years ago — and temperatures in Greenland rose 10 degrees Celsius in a decade.

Evidence for such dramatic climate shifts laid to rest any lingering ideas that global climate change would be slow and unlikely to occur on a timescale that humans should worry about. “It’s an important reminder of how ‘tippy’ things can be,” says Jessica Tierney, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

More evidence of global change came from Earth-observing satellites, which brought a new planet-wide perspective on global warming beginning in the 1960s. From their viewpoint in the sky, satellites have measured the steady rise in global sea level — currently 3.4 millimeters per year and accelerating, as warming water expands and as ice sheets melt — as well as the rapid decline in ice left floating on the Arctic Ocean each summer at the end of the melt season. Gravity-sensing satellites have ‘weighed’ the Antarctic and Greenlandic ice sheets from above since 2002, reporting that more than 400 billion metric tons of ice are lost each year.

Temperature observations taken at weather stations around the world also confirm that we are living in the hottest years on record. The 10 warmest years since record keeping began in 1880 have all occurred since 2005. And nine of those 10 have come since 2010.

What’s more, extreme weather is hammering the planet more and more frequently. That 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, for instance, is just a harbinger of what’s to come. — Alexandra Witze

Worrisome predictions from climate models

By the 1960s, there was no denying that the planet was warming. But understanding the consequences of those changes — including the threat to human health and well-being — would require more than observational data. Looking to the future depended on computer simulations: complex calculations of how energy flows through the planetary system. Such models of the climate system have been crucial to developing projections for what we can expect from greenhouse warming.

A first step in building climate models was to connect everyday observations of weather to the concept of forecasting future climate. During World War I, the British mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson imagined tens of thousands of meteorologists working to forecast the weather, each calculating conditions for a small part of the atmosphere but collectively piecing together a global forecast. Richardson published his work in 1922, to reviews that called the idea “of almost quixotic boldness.”

But it wasn’t until after World War II that computational power turned Richardson’s dream into reality. In the wake of the Allied victory, which relied on accurate weather forecasts for everything from planning D-Day to figuring out when and where to drop the atomic bombs, leading U.S. mathematicians acquired funding from the federal government to improve predictions. In 1950 a team led by Jule Charney, a meteorologist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., used the ENIAC, the first general-purpose, programmable electronic computer, to produce the first computer-driven regional weather forecast . The forecasting was slow and rudimentary, but it built on Richardson’s ideas of dividing the atmosphere into squares, or cells, and computing the weather for each of those. With the obscure title “Numerical integration of the barotropic vorticity equation,” the paper reporting the results set the stage for decades of climate modeling to follow.

By 1956 Norman Phillips, a member of Charney’s team, had produced the world’s first general circulation model, which captured how energy flows between the oceans, atmosphere and land. Phillips ran the calculations on a computer with just 5 kilobytes of memory, yet it was able to reproduce monthly and seasonal patterns in the lower atmosphere. That meant scientists could begin developing more realistic models of how the planet responds to factors such as increasing levels of greenhouse gases. The field of climate modeling was born.

The work was basic at first, because early computers simply didn’t have much computational power to simulate all aspects of the planetary system. “People thought that it was stupid to try to study this greenhouse-warming issue by three-dimensional model[s], because it cost so much computer time,” meteorologist Syukuro Manabe told physics historian Spencer Weart in a 1989 oral history .

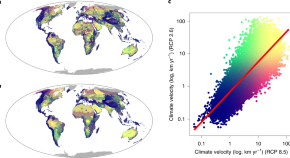

Climate models have predicted how much ice the Ilulissat region of the Greenland ice sheet might lose by 2300 based on different scenarios for greenhouse gas emissions. The models are compared to 2008 (first image). In a best-case scenario, in which emissions peak by mid-century, the speed at which the glacier is sending ice out into the ocean is much lower (second image) than with a worst-case scenario, in which emissions rise at a high rate (third image).

An important breakthrough came in 1967, when Manabe and Richard Wetherald — both at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, a lab born from Charney’s group — published a paper in the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences that modeled connections between Earth’s surface and atmosphere and calculated how changes in carbon dioxide would affect the planet’s temperature. Manabe and Wetherald were the first to build a computer model that captured the relevant processes that drive climate , and to accurately simulate how the Earth responds to those processes. (Manabe shared the 2021 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on climate modeling; Wetherald died in 2011.)

The rise of climate modeling allowed scientists to more accurately envision the impacts of global warming. In 1979, Charney and other experts met in Woods Hole, Mass., to try to put together a scientific consensus on what increasing levels of CO 2 would mean for the planet. They analyzed climate models from Manabe and from James Hansen of NASA. The resulting “Charney report” concluded that rising CO 2 in the atmosphere would lead to additional and significant climate change. The ocean might take up much of that heat, the scientists wrote — but “it appears that the warming will eventually occur, and the associated regional climatic changes so important to the assessment of socioeconomic consequence may well be significant.”

In the decades since, climate modeling has gotten increasingly sophisticated . Scientists have drawn up a variety of scenarios for how carbon emissions might change in the future, depending on the stringency of emissions cuts. Modelers use those scenarios to project how climate and weather will change around the globe, from hotter croplands in China to melting glaciers in the Himalayas. Climate simulations have also allowed researchers to identify the fingerprints of human impacts on extreme weather that is already happening, by comparing scenarios that include the influence of human activities with those that do not.

And as climate science firmed up and the most dramatic consequences became clear, the political battles raged. — Alexandra Witze

Climate science meets politics

With the development of climate science tracing back to the early Cold War, perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise that the science of global warming became enmeshed in broader societal and political battles. A complex stew of political, national and business interests mired society in debates about the reality of climate change, and what to do about it, decades after the science became clear that humans are fundamentally altering the planet’s atmosphere.

Society has pulled itself together before to deal with global environmental problems, such as the Antarctic ozone hole. In 1974 chemists Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland, both of the University of California, Irvine, reported that chlorofluorocarbon chemicals, used in products such as spray cans and refrigerants, caused a chain of reactions that gnawed away at the atmosphere’s protective ozone layer . The resulting ozone hole, which forms over Antarctica every spring, allows more ultraviolet radiation from the sun to make it through Earth’s atmosphere and reach the surface, where it can cause skin cancer and eye damage.

Governments ultimately worked under the auspices of the United Nations to craft the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which strictly limited the manufacture of chlorofluorocarbons . In the years following, the ozone hole began to heal. But fighting climate change would prove to be far more challenging. Chlorofluorocarbons were a suite of chemicals with relatively limited use and for which replacements could be found without too much trouble. But the greenhouse gases that cause global warming stem from a wide variety of human activities, from energy development to deforestation. And transforming entire energy sectors to reduce or eliminate carbon emissions is much more difficult than replacing a set of industrial chemicals.

In 1980, though, researchers took an important step toward banding together to synthesize the scientific understanding of climate change and bring it to the attention of international policy makers. It started at a small scientific conference in Villach, Austria. There, experts met under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization, the International Council of Scientific Unions and the United Nations Environment Program to discuss the seriousness of climate change. On the train ride home from the meeting, Swedish meteorologist Bert Bolin talked with other participants about how a broader, deeper and more international analysis was needed. In 1985, a second conference was held at Villach to highlight the urgency, and in 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, was born. Bolin was its first chairperson.

The IPCC became a highly influential and unique body. It performs no original scientific research; instead, it synthesizes and summarizes the vast literature of climate science for policy makers to consider — primarily through massive reports issued every couple of years. The first IPCC report , in 1990, predicted that the planet’s global mean temperature would rise more quickly in the following century than at any point in the last 10,000 years, due to increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Successive IPCC reports showed more and more confidence in the link between greenhouse emissions and rising global temperatures — and explored how society might mitigate and adapt to coming changes.

IPCC reports have played a key role in providing scientific information for nations discussing how to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations. This process started with the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 , which resulted in the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Annual U.N. meetings to tackle climate change led to the first international commitments to reduce emissions, the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. Under it, developed countries committed to reduce emissions of CO 2 and other greenhouse gases. By 2007 the IPCC declared that the reality of climate warming is “unequivocal ”; the group received the Nobel Peace Prize that year along with Al Gore for their work on climate change.

The IPCC process ensured that policy makers had the best science at hand when they came to the table to discuss cutting emissions. “If you go back and look at the original U.N. framework on climate change, already you see the core of the science represented there,” says Rachel Cleetus, a climate policy expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists in Cambridge, Mass. Of course, nations did not have to abide by that science — and they often didn’t.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, international climate meetings discussed less hard-core science and more issues of equity. Countries such as China and India pointed out that they needed energy to develop their economies, and that nations responsible for the bulk of emissions through history, such as the United States, needed to lead the way in cutting greenhouse gases. Meanwhile, residents of some of the most vulnerable nations, such as low-lying islands that are threatened by sea level rise, gained visibility and clout at international negotiating forums. “The issues around equity have always been very uniquely challenging in this collective action problem,” says Cleetus.

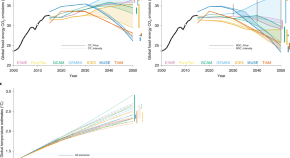

By 2015, the world’s nations had made some progress on the emissions cuts laid out in the Kyoto Protocol, but it was still not enough to achieve substantial global reductions. That year, a key U.N. climate conference in Paris produced an international agreement to try to limit global warming to 2 degrees C , and preferably 1.5 degrees C, above preindustrial levels.

Every country has its own approach to the challenge of addressing climate change. In the United States, which gets approximately 80 percent of its energy from fossil fuels, sophisticated efforts to downplay and critique the science led to major delays in climate action. For decades U.S. fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil worked to influence politicians to take as little action on emissions reductions as possible. Working with a small group of influential scientists, this well-funded, well-orchestrated campaign took many of its tactics from earlier tobacco-industry efforts to cast doubt on the links between smoking and cancer, as historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway documented in their book Merchants of Doubt.

Perhaps the peak of U.S. climate denialism came in the late 1980s and into the 1990s — roughly a century after Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius laid out the consequences of putting too much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In 1988 NASA scientist James Hansen testified to lawmakers about the consequences of global warming. “It is already happening now,” Hansen said, summarizing what scientists had long known.

The high-profile nature of Hansen’s testimony, combined with his NASA expertise, vaulted global warming into the public eye in the United States like never before. “It really hit home with a public who could understand that there are reasons that Venus is hot and Mars is cold,” says Joshua Howe, a historian at Reed College. “And that if you use that same reasoning, we have some concerns about what is happening here on Earth.” But Hansen also kicked off a series of bitter public battles about the reality of human-caused climate change that raged for years.

One common approach of climate skeptics was to attack the environmental data and models that underlie climate science. In 1998, scientist Michael Mann, then at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, and colleagues published a detailed temperature record that formed the basis of what came to be known as the “hockey stick” graph, so named because the chart showed a sharp rise in temperatures (the hockey blade) at the end of a long, much flatter period (the hockey stick). Skeptics soon demanded the data and software processing tools Mann used to create the graph. Bloggers and self-proclaimed citizen scientists created a cottage industry of questioning new climate science papers under the guise of “audits.” In 2009 hackers broke into a server at the University of East Anglia, a leading climate-research hub in Norwich, England, and released more than 1,000 e-mails between climate scientists. This “Climategate” scandal purported to reveal misconduct on the part of the researchers, but several reviews largely exonerated the scientists.

The graph that launched climate skeptic attacks

This famous graph, produced by scientist Michael Mann and colleagues, and then reproduced in a 2001 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, dramatically captures temperature change over time. Climate change skeptics made it the center of an all-out attack on climate science.

Such tactics undoubtedly succeeded in feeding politicians’ delay on climate action in the United States, most of it from Republicans. President George W. Bush withdrew the country from the Kyoto Protocol in 2001 ; Donald Trump similarly rejected the Paris accord in 2017 . As late as 2015, the chair of the Senate’s environment committee, James Inhofe of Oklahoma, brought a snowball into Congress on a cold winter’s day in order to continue his argument that human-caused global warming is a “hoax.” In Australia, a similar mix of right-wing denialism and fossil fuel interests has kept climate change commitments in flux, as prime ministers are voted in and out over fierce debates about how the nation should act on climate.

Yet other nations have moved forward. Some European countries such as Germany aggressively pursued renewable energies, such as wind and solar, while activists such as the Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg — the vanguard of a youth-action movement — pressured their governments for more.

In recent years the developing economies of China and India have taken center stage in discussions about climate action. Both nations argue that they must be allowed extra time to wean themselves off fossil fuels in order to continue economic growth. They note that historically speaking, the United States is the largest total emitter of carbon by far.

Total carbon dioxide emissions by country, 1850–2021

These 20 nations have emitted the largest cumulative amounts of carbon dioxide since 1850. Emissions are shown in in billions of metric tons and are broken down into subtotals from fossil fuel use and cement manufacturing (blue) as well as from land use and forestry (green).

China, whose annual CO 2 emissions surpassed those of the United States in 2006, declared several moderate steps in 2021 to reduce emissions, including that it would stop building coal-burning power plants overseas. India announced it would aim for net-zero emissions by 2070, the first time it has set a date for this goal.

Yet such pledges continue to be criticized. At the 2021 U.N. Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, India was globally criticized for not committing to a complete phaseout of coal — although the two top emitters, China and the United States, have not themselves committed to phasing out coal. “There is no equity in this,” says Aayushi Awasthy, an energy economist at the University of East Anglia. — Alexandra Witze

Facing a warmer future

Climate change creeps up gradually on society, except when it doesn’t. The slow increase in sea level, for instance, causes waters to lap incrementally higher at shorelines year after year. But when a big storm comes along — which may be happening more frequently due to climate change — the consequences become much more obvious. Storm surge rapidly swamps communities and wreaks disproportionate havoc. That’s why New York City installed floodgates in its subway and tunnel system in the wake of 2012’s Superstorm Sandy , and why the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu has asked Australia and New Zealand to be prepared to take in refugees fleeing from rising sea levels.

The list of climate impacts goes on and on — and in many cases, changes are coming faster than scientists had envisioned a few decades ago. The oceans are becoming more acidic as they absorb carbon dioxide, harming tiny marine organisms that build protective calcium carbonate shells and are the base of the marine food web. Warmer waters are bleaching coral reefs. Higher temperatures are driving animal and plant species into areas in which they previously did not live, increasing the risk of extinction for many. “It’s no longer about impacts in the future,” says Rachel Cleetus, a climate policy expert at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “It’s about what’s happening in the U.S. here and now, and around the world.”

No place on the planet is unaffected. In many areas, higher temperatures have led to major droughts, which dry out vegetation and provide additional fuel for wildfires such as those that have devastated Australia , the Mediterranean and western North America in recent years. The Colorado River , the source of water for tens of millions of people in the western United States , came under a water-shortage alert in 2021 for the first time in history.

Then there’s the Arctic, where temperatures are rising at more than twice the global average and communities are at the forefront of change. Permafrost is thawing, destabilizing buildings, pipelines and roads. Caribou and reindeer herders worry about the increased risk of parasites to the health of their animals. With less sea ice available to buffer the coast from storm erosion, the Inupiat village of Shishmaref, Alaska, risks crumbling into the sea. It will need to move from its sand-barrier island to the mainland .

“We know these changes are happening and that the Titanic is sinking,” says Louise Farquharson, a geomorphologist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks who monitors permafrost and coastal change around Alaska. Like many Arctic scientists, she is working with Indigenous communities to understand the shifts they’re experiencing and what can be done when buildings start to slump and water supplies start to drain away. “A big part is just listening to community members and understanding what they’re seeing change,” she says.

All around the planet, those who depend on intact ecosystems for their survival face the greatest threat from climate change. And those with the least resources to adapt to climate change are the ones who feel it first .

“We are going to warm,” says Claudia Tebaldi, a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “There is no question about it. The only thing that we can hope to do is to warm a little more slowly.”

That’s one reason why the IPCC report released in 2021 focuses on anticipated levels of global warming. There is a big difference between the planet warming 1.5 degrees versus 2 degrees or 2.5 degrees. Consider that we are now at least 1.1 degrees above preindustrial levels of CO 2 and are already seeing dramatic shifts in climate. Given that, keeping further global temperature increases as low as possible will make a big difference in the climate impacts the planet faces. “With every fraction of a degree of warming, everything gets a little more intense,” says paleoclimatologist Jessica Tierney. “There’s no more time to beat around the bush.”

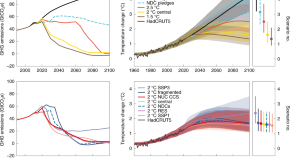

Historical and projected global temperature change

Various scenarios for how greenhouse gas emissions might change going forward help scientists predict future climate change. This graph shows the simulated historical temperature trend along with future projections of global surface temperature based on five scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Temperature change is the difference from the 1850–1900 average.

The future rests on how much nations are willing to commit to cutting emissions and whether they will stick to those commitments. It’s a geopolitical balancing act the likes of which the world has never seen.

Science can and must play a role going forward. Improved climate models will illuminate what changes are expected at the regional scale, helping officials prepare. Governments and industry have crucial parts to play as well. They can invest in technologies, such as carbon sequestration, to help decarbonize the economy and shift society toward more renewable sources of energy. “We can solve these problems — most of the tools are already there,” says Cascade Tuholske, a geographer at Columbia University. “We just have to do it.”

Huge questions remain. Do voters have the will to demand significant energy transitions from their governments? How can business and military leaders play a bigger role in driving climate action? What should be the role of low-carbon energy sources that come with downsides, such as nuclear energy ? How can developing nations achieve a better standard of living for their people while not becoming big greenhouse gas emitters? How can we keep the most vulnerable from being disproportionately harmed during extreme events, and incorporate environmental and social justice into our future?

These questions become more pressing each year, as CO 2 accumulates in our atmosphere. The planet is now at higher levels of CO 2 than at any time in the last 3 million years. Yet Ralph Keeling, keeper of the iconic Mauna Loa record tracking the rise in atmospheric CO 2 , is already optimistically thinking about how scientists would be able to detect a slowdown, should the world actually start cutting emissions by a few percent per year. “That’s what the policy makers want to see — that there’s been some large-scale impact of what they did,” he says.

At the 2021 U.N. climate meeting in Glasgow diplomats from around the world agreed to work more urgently to shift away from using fossil fuels. They did not, however, adopt targets strict enough to keep the world below a warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius. It’s been well over a century since Svante Arrhenius recognized the consequences of putting extra carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and yet world leaders have yet to pull together to avoid the most dangerous consequences of climate change.

Time is running out. — Alexandra Witze

Climate change facts

We know that climate change and its consequences are real, and we are responsible. Here’s what the science tells us.

How much has the planet warmed over the past century?

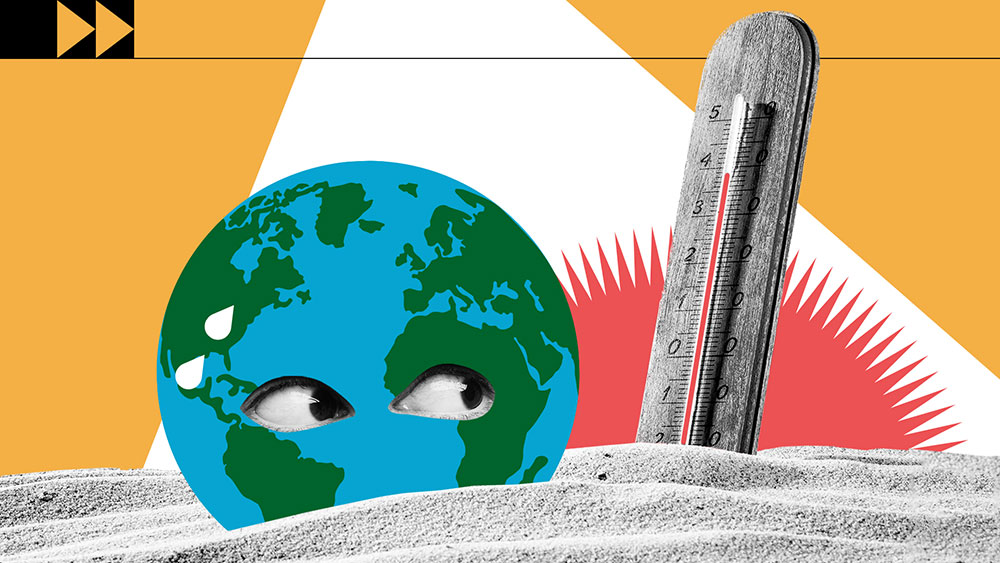

The planet’s average surface temperature has risen by at least 1.1 degree Celsius since preindustrial levels of 1850–1900.

What is causing climate change?

People are loading the atmosphere with carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases produced during the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal and gas, and cutting down forests.

What are some of the effects of climate change?

Ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are melting, raising sea levels and flooding low-lying island nations and coastal cities. Drought is parching farmlands and the rivers that feed them. Wildfires are raging. Rains are becoming more intense, and weather patterns are shifting.

What is the greenhouse effect?

In the 19th century, Irish physicist John Tyndall found that carbon dioxide gas, as well as water vapor, absorbed more heat than air alone. He argued that such gases would trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, much as panes of glass trap heat in a greenhouse, and thus modulate climate.

What is the Keeling curve?

One of the most iconic datasets in all of science, the Keeling curve tracks the rise of atmospheric CO 2 . When geochemist Charles David Keeling began his measurements in 1958 on the Hawaiian volcano of Mauna Loa, CO 2 made up 315 parts per million of the global atmosphere. Each year the curve keeps going up: In 2016 it passed 400 ppm of CO 2 in the atmosphere, as measured during its typical annual minimum in September. In 2021, the annual minimum was 413 ppm.

Does it get hotter every year?

Average global temperatures fluctuate from year to year, but temperature observations taken at weather stations around the world confirm that we are living in the hottest years on record. The 10 warmest years since record keeping began in 1880 have all occurred since 2005. And nine of those 10 have come since 2010.

What countries emit the most carbon dioxide?

The United States has been the largest total emitter of carbon dioxide by far, followed by China and Russia. China’s annual CO 2 emissions surpassed those of the United States in 2006.

What places are impacted by climate change?

No place on the planet is unaffected. Higher temperatures have led to major droughts, providing fuel for wildfires such as those that have devastated Australia , the Mediterranean and western North America in recent years. The Colorado River came under a water-shortage alert in 2021 for the first time in history. In the Arctic, where temperatures are rising at more than twice the global average, permafrost is thawing, destabilizing buildings, pipelines and roads. With less sea ice available to buffer the coast from storm erosion, the Inupiat village of Shishmaref, Alaska, risks crumbling into the sea. All around the planet, those who depend on intact ecosystems for their survival face the greatest threat from climate change. And those with the least resources to adapt to climate change are the ones who feel it first .

Editor’s note: This story was published March 10, 2022.

British mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson (shown at center) proposes forecasting the weather by piecing together the calculations of tens of thousands of meteorologists working on small parts of the atmosphere.

Geochemist Charles David Keeling (shown in 1988) begins tracking the rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa in Hawaii. The record, which continues through today, has become one of the most iconic datasets in all of science.

Rachel Carson (shown) publishes the book Silent Spring , raising alarm over the ecological impacts of the pesticide DDT. The book helps catalyze the modern U.S. environmental movement.

The first Earth Day, organized by U.S. senator Gaylord Nelson and graduate student Denis Hayes, is celebrated.

The first Landsat satellite launched (shown), opening the door to continuous monitoring of Earth and its features from above.

A powerful eruption from the Philippines’ Mount Pinatubo (shown) ejects millions of tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, temporarily cooling the planet.

World leaders gathered (shown) at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro to address how to pursue economic development while also protecting the Earth. The meeting resulted in an international convention on climate change.

Activist Greta Thunberg initiates the “School Strike for Climate” movement by protesting outside the Swedish parliament. Soon, students around the world join a growing movement demanding action on climate change . (Activists at the 2021 U.N. Climate Change Conference are shown.)

From the archive

Climate change foreseen.

In an early mention of climate change in Science News-Letter , the predecessor of Science News , British meteorologist C.E.P. Brooks warns that present warming trends could lead to “important economic and political effects.”

IGY Brings Many Discoveries

Science News Letter lists the Top 8 accomplishments of the International Geophysical Year.

Chilling possibilities

Science News explores the tentative idea that global temperatures are cooling and that a new ice age could be imminent, which is later shown to be inaccurate.

Long Hot Future: Warmer Earth Appears Inevitable

“The planet earth will be a warmer place in the 21st century, and there is no realistic strategy that can prevent the change,” Science News reports.

Ozone and Global Warming: What to Do?

Policy makers discuss how to solve the dual problems of ozone depletion and global warming.

Looking for Mr. Greenhouse

Science writer Richard Monastersky reports on scientists’ efforts to evaluate how to connect increasing greenhouse gases and a warming climate.

World Climate Panel Charts Path for Action

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports that “the fingerprint of man in the past temperature record” is now apparent.

Animals on the Move

A warming climate means shifting ranges and ecosystem disruptions for a lot of species, Nancy Ross-Flanigan reports.

Changing climate: 10 years after ‘An Inconvenient Truth’

A decade after former vice president Al Gore releases the documentary film An Inconvenient Truth , Science News looks back at how climate science has advanced.

With nowhere to hide from rising seas, Boston prepares for a wetter future

Mary Caperton Morton reports for Science News on how Boston is taking action to prepare for rising seas.

The new UN climate change report shows there’s no time for denial or delay

Earth & climate writer Carolyn Gramling covers the sixth assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which documents how climate change is already affecting every region on Earth.

Climate change disinformation is evolving. So are efforts to fight back

Researchers are testing games and other ways to help people recognize climate change denial.

Extreme weather in 2022 showed the global impact of climate change

Heat waves, floods, wildfires and drought around the world were exacerbated by Earth’s changing climate.

It’s possible to reach net-zero carbon emissions. Here’s how

Cutting carbon dioxide emissions to curb climate change and reach net zero is possible but not easy.

The last 12 months were the hottest on record

The planet’s average temperature was about 1.3 degrees Celsius higher than the 1850–1900 average, a new report finds.

Science News is published by Society for Science

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

4 guidelines for writing about climate change

The climate story has moved beyond science and is increasingly local . It touches communities and coverage in new ways every day. As you cover the topic in your area, here are some guidelines for your reporting.

Do not conflate science and policy. They are separate things. Science informs policymaking but it does not dictate what policies should be chosen. Different people may reach different conclusions, depending on what they value.

Be specific about which climate change “debate” you are covering. There is no single debate; there are separate debates within science, within policy and within economics, and debates about how scientific findings should guide policy.

Be clear about the science. The overarching issue is as settled as things get in science: The planet is warming and humans are largely responsible. As a result, glaciers and ice sheets are melting. New, contradictory evidence could come along–science is always subject to revision. But the idea that humans are causing climate change is not scientifically controversial.

Avoid “global warming: yes or no?” coverage. Although there are still many scientific questions to be answered, the climate change story has shifted to policy. What should we do, if anything, about climate change? Just as governments routinely make decisions about fiscal policy under great uncertainty, environmental policy can proceed even though scientific uncertainties remain.

Taken from Covering Climate Change , a self-directed course by Tom Yulsman at Poynter NewsU .

Take the full course

Have you missed a Coffee Break Course? Here’s our complete lineup . Or follow along on Twitter at #coffeebreakcourse.

Associated Press Stylebook makes Merriam-Webster its official dictionary

If a term isn’t listed in the stylebook, its entry in Merriam-Webster will be considered AP style.

Opinion | What’s going on with the NFL Network?

The NFL appears to be sabotaging ‘Good Morning Football,’ one of the best sports studio shows on TV. Why?

Are you an early-career reporter looking to level up? We’re here to help.

Pulitzer Prize winner Kat McGrory is one of the instructors in Poynter's upcoming Reporter's Toolkit training program

No, crime has not ‘skyrocketed’ under Joe Biden, as Rep. Nancy Mace claimed

Overall violent crime and homicides are down during Biden’s presidency. Some property crimes are also down, though motor vehicle theft notably rose

Opinion | What’s next for Disney and CEO Bob Iger after a record-breakingly expensive corporate proxy fight?

Iger’s current contract runs through 2026. Then what?

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

- Education home

- About NOAA Education

- NOAA in your backyard: Alaska

- NOAA in your backyard: Caribbean

- NOAA in your backyard: Central

- NOAA in your backyard: Great Lakes

- NOAA in your backyard: Gulf of Mexico

- NOAA in your backyard: Mid-Atlantic

- NOAA in your backyard: Northeast

- NOAA in your backyard: Northwest

- NOAA in your backyard: Pacific Islands

- NOAA in your backyard: Southeast

- NOAA in your backyard: Southwest

- Educational mailing lists

- Oct-Dec 2023

- Jul-Sep 2023

- Apr-Jun 2023

- Jan-Mar 2023

- NOAA Sea to Sky: Education resource database

- Ocean acidification

- Ocean currents

- Ocean floor features

- Ocean pollution and marine debris

- El Niño and La Niña

- Space weather

- Weather observations

- Weather systems & patterns

- Carbon cycle

- Changing seasons

Climate change impacts

- Climate data monitoring

- Aquatic food webs

- Coral reef ecosystems

- Fisheries and seafood

- Life in an estuary

- Marine mammals

- Sea turtles

- Great Lakes ecoregion

- Water cycle

- Watersheds, flooding, and pollution

- Data resources for educators

- Education at home

- Elementary resources

- Hands-on science activities

- Special topics

- Conference resources

- About the education resource collections

- Conservation Service Corp Act Direct Hiring Authority

- Educator opportunities

- Grants & networks

- News and stories

Keep exploring

Find even more resources on climate change impacts in our searchable resource database.

CLEAN Collection offsite link

Sanctuaries resource collection: Climate change

Though we often think about human-induced climate change as something that will happen in the future, it is an ongoing process. Ecosystems and communities in the United States and around the world are being impacted today.

A collage of typical climate and weather-related events: floods, heatwaves, drought, hurricanes, wildfires and loss of glacial ice. (Image credit: NOAA)

Global temperatures rose about 1.98°F offsite link (1.1°C) from 1901 to 2020, but climate change refers to more than an increase in temperature. It also includes sea level rise, changes in weather patterns like drought and flooding, and much more. Things that we depend upon and value — water, energy, transportation, wildlife, agriculture, ecosystems, and human health — are experiencing the effects of a changing climate.

A complex issue

The impacts of climate change on different sectors of society are interrelated. Drought can harm food production and human health. Flooding can lead to disease spread and damages to ecosystems and infrastructure. Human health issues can increase mortality, impact food availability, and limit worker productivity. Climate change impacts are seen throughout every aspect of the world we live in. However, climate change impacts are uneven across the country and the world — even within a single community, climate change impacts can differ between neighborhoods or individuals. Long-standing socioeconomic inequities can make underserved groups, who often have the highest exposure to hazards and the fewest resources to respond, more vulnerable.

The projections of a climate change-impacted future are not inevitable. Many of the problems and solutions offsite link are known to us now, and ongoing research continues to provide new ones. Experts believe there is still time to avoid the most negative of outcomes by limiting warming offsite link and reducing emissions to zero as quickly as possible. Reducing our emissions of greenhouse gases will require investment in new technology and infrastructure, which will spur job growth. Additionally, lowering emissions will lessen harmful impacts to human health, saving countless lives and billions of dollars in health-related expenses.

Levels of the two most important anthropogenic greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide and methane, continued their unrelenting rise in 2020 despite the economic slowdown caused by the coronavirus pandemic response.

Our changing climate

We see climate change affecting our planet from pole to pole. NOAA monitors global climate data and here are some of the changes NOAA has recorded. You can explore more at the Global Climate Dashboard .

- Global temperatures rose about 1.8°F (1°C) from 1901 to 2020.

- Sea level rise has accelerated from 1.7 mm/year throughout most of the twentieth century to 3.2 mm/year since 1993.

- Glaciers are shrinking: average thickness of 30 well-studied glaciers has decreased more than 60 feet since 1980.

- The area covered by sea ice in the Arctic at the end of summer has shrunk by about 40% since 1979.

- The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen by 25% since 1958, and by about 40% since the Industrial Revolution.

- Snow is melting earlier compared to long-term averages.

Changes to water resources can have a big impact on our world and our lives.

Flooding is an increasing issue as our climate is changing. Compared to the beginning of the 20th century, there are both stronger and more frequent abnormally heavy precipitation events across most of the United States.

Conversely, drought is also becoming more common , particularly in the Western United States. Humans are using more water, especially for agriculture. Much like we sweat more when it is hot out, higher air temperatures cause plants to lose, or transpire , more water, meaning farmers must give them more water. Both highlight the need for more water in places where supplies are dwindling.

Snowpack is an important source of fresh water for many people. As the snow melts, fresh water becomes available for use, especially in regions like the Western United States where there is not much precipitation in warmer months. But as temperatures warm, there is less snow overall and snow begins to melt earlier in the year, meaning snowpack may not be a reliable source of water for the entire warm and dry seasons.

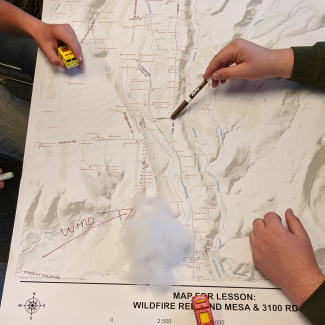

The Redlands Mesa area outside Hotchkiss, Colorado, is particularly at risk to wildfires, but with funding from NOAA’s Environmental Literacy Program, local high school students are taking action to tackle their community’s vulnerability to this hazard.

Our food supply depends on climate and weather conditions. Although farmers and researchers may be able to adapt some agricultural techniques and technologies or develop new ones, some changes will be difficult to manage. Increased temperatures, drought and water stress, diseases, and weather extremes create challenges for the farmers and ranchers who put food on our tables.

Human farm workers can suffer from heat-related health issues , like exhaustion, heatstroke, and heart attacks. Rising temperatures and heat stress can also harm livestock.

Human health

Climate change is already impacting human health . Changes in weather and climate patterns can put lives at risk. Heat is one of the most deadly weather phenomena. As ocean temperatures rise, hurricanes are getting stronger and wetter , which can cause direct and indirect deaths . Dry conditions lead to more wildfires, which bring many health risks . Higher incidences of flooding can lead to the spread of waterborne diseases, injuries, and chemical hazards. As geographic ranges of mosquitoes and ticks expand, they can carry diseases to new locations.

The most vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, people with preexisting health conditions, outdoor workers, people of color, and people with low income, are at an even higher risk because of the compounding factors from climate change. But public health groups can work with local communities to help people understand and build resilience to climate change health impacts.

The environment

Climate change will continue to have a significant impact on ecosystems and organisms, though they are not impacted equally. The Arctic is one of the ecosystems most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, as it is warming at least twice the rate of the global average and melting land ice sheets offsite link and glaciers offsite link contribute dramatically to sea level rise around the globe.

Some living things are able to respond to climate change; some plants are blooming earlier and some species may expand their geographic range. But these changes are happening too fast for many other plants and animals as increasing temperatures and changing precipitation patterns stress ecosystems. Some invasive or nuisance species, like lionfish and ticks , may thrive in even more places because of climate change.

Changes are also occurring in the ocean. The ocean absorbs about 30% of the carbon dioxide that is released into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels. As a result, the water is becoming more acidic , affecting marine life. Sea levels are rising due to thermal expansion, in addition to melting ice sheets and glaciers, putting coastal areas at greater risk of erosion and storm surge.

The compounding effects of climate change are leading to many changes in ecosystems. Coral reefs are vulnerable to many effects of climate change: warming waters can lead to coral bleaching, stronger hurricanes can destroy reefs, and sea level rise can cause corals to be smothered by sediment. Coral reef ecosystems are home to thousands of species, which rely on healthy coral reefs to survive.

Infrastructure

Physical infrastructure includes bridges, roads, ports, electrical grids, broadband internet, and other parts of our transportation and communication systems. It is often designed to be in use for years or decades, and many communities have infrastructure that was designed without future climate in mind. But even newer infrastructures can be vulnerable to climate change.

Extreme weather events that bring heavy rains, floods, wind, snow, or temperature changes can stress existing structures and facilities. Increased temperatures require more indoor cooling, which can put stress on an energy grid. Sudden heavy rainfall can lead to flooding that shuts down highways and major business areas.

Nearly 40% of the United States population lives in coastal counties, meaning millions of people will be impacted by sea level rise. Coastal infrastructure , such as roads, bridges, water supplies, and much more, is at risk. Sea level rise can also lead to coastal erosion and high-tide flooding . Some communities are projected to possibly end up at or below sea level by 2100 and will face decisions around managed retreat and climate adaptation.

Many communities are not yet prepared to face climate-related threats. Even within a community, some groups are more vulnerable to these threats than others. Going forward, it is important for communities to invest in resilient infrastructure that will be able to withstand future climate risks. Researchers are studying current and future impacts of climate change on communities and can offer recommendations on best practices. Resilience education is vitally important for city planners, emergency managers, educators, communicators, and all other community members to prepare for climate change.

EDUCATION CONNECTION

Teaching about climate change can be a daunting challenge, but it is a critical field for students to learn about, as it affects many parts of society. The Essential Principles of Climate Literacy , developed by NOAA and other federal partners, are standards that create a framework for teaching climate. The Toolbox for Teaching Climate & Energy explores a learning process to help students engage in climate action in their own communities or on a global scale. For more educator support, NOAA offers professional development opportunities (including the Planet Stewards Program ) about climate and other topics.

Search the United Nations

- What Is Climate Change

- Myth Busters

- Renewable Energy

- Finance & Justice

- Initiatives

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Paris Agreement

- Climate Ambition Summit 2023

- Climate Conferences

- Press Material

- Communications Tips

What Is Climate Change?

Climate change refers to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. Such shifts can be natural, due to changes in the sun’s activity or large volcanic eruptions. But since the 1800s, human activities have been the main driver of climate change , primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas.

Burning fossil fuels generates greenhouse gas emissions that act like a blanket wrapped around the Earth, trapping the sun’s heat and raising temperatures.

The main greenhouse gases that are causing climate change include carbon dioxide and methane. These come from using gasoline for driving a car or coal for heating a building, for example. Clearing land and cutting down forests can also release carbon dioxide. Agriculture, oil and gas operations are major sources of methane emissions. Energy, industry, transport, buildings, agriculture and land use are among the main sectors causing greenhouse gases.

Humans are responsible for global warming

Climate scientists have showed that humans are responsible for virtually all global heating over the last 200 years. Human activities like the ones mentioned above are causing greenhouse gases that are warming the world faster than at any time in at least the last two thousand years.

The average temperature of the Earth’s surface is now about 1.1°C warmer than it was in the late 1800s (before the industrial revolution) and warmer than at any time in the last 100,000 years. The last decade (2011-2020) was the warmest on record , and each of the last four decades has been warmer than any previous decade since 1850.