Call our 24 hours, seven days a week helpline at 800.272.3900

- Professionals

- Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer's

- Is Alzheimer's Genetic?

- Women and Alzheimer's

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- Down Syndrome & Alzheimer's

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Know the 10 Signs

- Difference Between Alzheimer's & Dementia

- 10 Steps to Approach Memory Concerns in Others

- Medical Tests for Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Why Get Checked?

- Visiting Your Doctor

- Life After Diagnosis

- Stages of Alzheimer's

- Earlier Diagnosis

- Part the Cloud

- Research Momentum

- Our Commitment to Research

- TrialMatch: Find a Clinical Trial

- What Are Clinical Trials?

- How Clinical Trials Work

- When Clinical Trials End

- Why Participate?

- Talk to Your Doctor

- Clinical Trials: Myths vs. Facts

- Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented?

- Brain Donation

- Navigating Treatment Options

- Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease

- Aducanumab Discontinued as Alzheimer's Treatment

- Medicare Treatment Coverage

- Donanemab for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease — News Pending FDA Review

- Questions for Your Doctor

- Medications for Memory, Cognition and Dementia-Related Behaviors

- Treatments for Behavior

- Treatments for Sleep Changes

- Alternative Treatments

- Facts and Figures

- Assessing Symptoms and Seeking Help

- Now is the Best Time to Talk about Alzheimer's Together

- Daily Care Plan

- Communication and Alzheimer's

- Food and Eating

- Art and Music

- Incontinence

- Dressing and Grooming

- Dental Care

- Working With the Doctor

- Medication Safety

- Accepting the Diagnosis

- Early-Stage Caregiving

- Middle-Stage Caregiving

- Late-Stage Caregiving

- Aggression and Anger

- Anxiety and Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Memory Loss and Confusion

- Sleep Issues and Sundowning

- Suspicions and Delusions

- In-Home Care

- Adult Day Centers

- Long-Term Care

- Respite Care

- Hospice Care

- Choosing Care Providers

- Finding a Memory Care-Certified Nursing Home or Assisted Living Community

- Changing Care Providers

- Working with Care Providers

- Creating Your Care Team

- Long-Distance Caregiving

- Community Resource Finder

- Be a Healthy Caregiver

- Caregiver Stress

- Caregiver Stress Check

- Caregiver Depression

- Changes to Your Relationship

- Grief and Loss as Alzheimer's Progresses

- Home Safety

- Dementia and Driving

- Technology 101

- Preparing for Emergencies

- Managing Money Online Program

- Planning for Care Costs

- Paying for Care

- Health Care Appeals for People with Alzheimer's and Other Dementias

- Social Security Disability

- Medicare Part D Benefits

- Tax Deductions and Credits

- Planning Ahead for Legal Matters

- Legal Documents

- Get Educated

- Just Diagnosed

- Sharing Your Diagnosis

- Changes in Relationships

- If You Live Alone

- Treatments and Research

- Legal Planning

- Financial Planning

- Building a Care Team

- End-of-Life Planning

- Programs and Support

- Overcoming Stigma

- Younger-Onset Alzheimer's

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Reducing Stress

- Tips for Daily Life

- Helping Family and Friends

- Leaving Your Legacy

- Live Well Online Resources

- Make a Difference

- ALZ Talks Virtual Events

- ALZNavigator™

- Veterans and Dementia

- The Knight Family Dementia Care Coordination Initiative

- Online Tools

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Alzheimer's

- Native Americans and Alzheimer's

- Black Americans and Alzheimer's

- Hispanic Americans and Alzheimer's

- LGBTQ+ Community Resources for Dementia

- Educational Programs and Dementia Care Resources

- Brain Facts

- 50 Activities

- For Parents and Teachers

- Resolving Family Conflicts

- Holiday Gift Guide for Caregivers and People Living with Dementia

- Trajectory Report

- Resource Lists

- Search Databases

- Publications

- Favorite Links

- 10 Healthy Habits for Your Brain

- Stay Physically Active

- Adopt a Healthy Diet

- Stay Mentally and Socially Active

- Online Community

- Support Groups

- Find Your Local Chapter

- Any Given Moment

- New IDEAS Study

- RFI Amyloid PET Depletion Following Treatment

- Bruce T. Lamb, Ph.D., Chair

- Christopher van Dyck, M.D.

- Cynthia Lemere, Ph.D.

- David Knopman, M.D.

- Lee A. Jennings, M.D. MSHS

- Karen Bell, M.D.

- Lea Grinberg, M.D., Ph.D.

- Malú Tansey, Ph.D.

- Mary Sano, Ph.D.

- Oscar Lopez, M.D.

- Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.

- About Our Grants

- Andrew Kiselica, Ph.D., ABPP-CN

- Arjun Masurkar, M.D., Ph.D.

- Benjamin Combs, Ph.D.

- Charles DeCarli, M.D.

- Damian Holsinger, Ph.D.

- David Soleimani-Meigooni, Ph.D.

- Donna M. Wilcock, Ph.D.

- Elizabeth Head, M.A, Ph.D.

- Fan Fan, M.D.

- Fayron Epps, Ph.D., R.N.

- Ganesh Babulal, Ph.D., OTD

- Hui Zheng, Ph.D.

- Jason D. Flatt, Ph.D., MPH

- Jennifer Manly, Ph.D.

- Joanna Jankowsky, Ph.D.

- Luis Medina, Ph.D.

- Marcello D’Amelio, Ph.D.

- Marcia N. Gordon, Ph.D.

- Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D.

- María Llorens-Martín, Ph.D.

- Nancy Hodgson, Ph.D.

- Shana D. Stites, Psy.D., M.A., M.S.

- Walter Swardfager, Ph.D.

- ALZ WW-FNFP Grant

- Capacity Building in International Dementia Research Program

- ISTAART IGPCC

- Alzheimer’s Disease Strategic Fund: Endolysosomal Activity in Alzheimer’s (E2A) Grant Program

- Imaging Research in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Zenith Fellow Awards

- National Academy of Neuropsychology & Alzheimer’s Association Funding Opportunity

- Part the Cloud-Gates Partnership Grant Program: Bioenergetics and Inflammation

- Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders (Invitation Only)

- Robert W. Katzman, M.D., Clinical Research Training Scholarship

- Funded Studies

- How to Apply

- Portfolio Summaries

- Supporting Research in Health Disparities, Policy and Ethics in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research (HPE-ADRD)

- Diagnostic Criteria & Guidelines

- Annual Conference: AAIC

- Professional Society: ISTAART

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: DADM

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: TRCI

- International Network to Study SARS-CoV-2 Impact on Behavior and Cognition

- Alzheimer’s Association Business Consortium (AABC)

- Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC)

- Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network

- International Alzheimer's Disease Research Portfolio

- Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Private Partner Scientific Board (ADNI-PPSB)

- Research Roundtable

- About WW-ADNI

- North American ADNI

- European ADNI

- Australia ADNI

- Taiwan ADNI

- Argentina ADNI

- WW-ADNI Meetings

- Submit Study

- RFI Inclusive Language Guide

- Scientific Conferences

- AUC for Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging

- Make a Donation

- Walk to End Alzheimer's

- The Longest Day

- RivALZ to End ALZ

- Ride to End ALZ

- Tribute Pages

- Gift Options to Meet Your Goals

- Founders Society

- Fred Bernhardt

- Anjanette Kichline

- Lori A. Jacobson

- Pam and Bill Russell

- Gina Adelman

- Franz and Christa Boetsch

- Adrienne Edelstein

- For Professional Advisors

- Free Planning Guides

- Contact the Planned Giving Staff

- Workplace Giving

- Do Good to End ALZ

- Donate a Vehicle

- Donate Stock

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Donate Gold & Sterling Silver

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Use of Funds

- Giving Societies

- Why We Advocate

- Ambassador Program

- About the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement

- Research Funding

- Improving Care

- Support for People Living With Dementia

- Public Policy Victories

- Planned Giving

- Community Educator

- Community Representative

- Support Group Facilitator or Mentor

- Faith Outreach Representative

- Early Stage Social Engagement Leaders

- Data Entry Volunteer

- Tech Support Volunteer

- Other Local Opportunities

- Visit the Program Volunteer Community to Learn More

- Become a Corporate Partner

- A Family Affair

- A Message from Elizabeth

- The Belin Family

- The Eliashar Family

- The Fremont Family

- The Freund Family

- Jeff and Randi Gillman

- Harold Matzner

- The Mendelson Family

- Patty and Arthur Newman

- The Ozer Family

- Salon Series

- No Shave November

- Other Philanthropic Activities

- Still Alice

- The Judy Fund E-blast Archive

- The Judy Fund in the News

- The Judy Fund Newsletter Archives

- Sigma Kappa Foundation

- Alpha Delta Kappa

- Parrot Heads in Paradise

- Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE)

- Sigma Alpha Mu

- Alois Society Member Levels and Benefits

- Alois Society Member Resources

- Zenith Society

- Founder's Society

- Joel Berman

- JR and Emily Paterakis

- Legal Industry Leadership Council

- Accounting Industry Leadership Council

Find Local Resources

Let us connect you to professionals and support options near you. Please select an option below:

Use Current Location Use Map Selector

Search Alzheimer’s Association

Double Match Challenge! Make 2x the Impact Today

- Models of Care Case Studies

The Alzheimer’s Association is committed to connecting clinicians to effective, evidence-based models of care that can be replicated in community settings. Two of these models — the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care program and the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative — are detailed below.

UCLA Alzheimer's and Dementia Care program Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care program

A dementia-specific model of care that significantly improved the experience for caregivers and people living with the disease.

About the program

The Alzheimer’s Association has partnered with UCLA to replicate the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care (ADC) program through a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. The program follows a co-management model within the UCLA health system and partners with community-based organizations (CBOs) to provide comprehensive, coordinated, individualized care for people living with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

The goals of the program are to:

- Maximize function, independence and dignity for people living with dementia.

- Minimize caregiver strain and burnout.

- Reduce unnecessary costs through improved care.

To qualify for the program, participants must have a diagnosis of dementia and live outside of a nursing home. The mean age of the first program participants was 82 years old. Almost all of the caregivers were the children (59%) or spouses (41%) of individuals living with Alzheimer’s or other dementias.

Comprehensive care

The ADC program utilizes a co-management model in which a nurse practitioner Dementia Care Specialist (DCS) partners with the participant’s primary care doctor to develop and implement a personalized care plan. The DCS provides support via four key components:

- Conducting in-person needs assessments of individuals living with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers.

- Creating and implementing individualized dementia care plans.

- Monitoring and revising care plans, as needed.

- Providing access 24/7, 365 days a year for assistance and advice to help avoid Emergency Department (ED) visits and hospitalizations.

Community resources

The ADC program also connects caregivers with resources provided by CBOs, including:

- Adult day care.

- Counseling.

- Case management.

- Legal and financial advice.

- Workforce development focused on training families and caregivers.

Program effectiveness

At one year, the quality of care provided by the program as measured by nationally accepted quality measures for dementia was exceedingly high — 92% compared to a benchmark of 38%. As a result, the improvements experienced by both caregivers and patients were significant:

- Ninety-four percent of caregivers felt that their role was supported.

- Ninety-two percent would recommend the program to others.

- Confidence in handling problems and complications of Alzheimer’s and other dementias improved by 79%.

- Caregiver distress related to behavioral symptoms, depression scores and strain improved by 31%, 24% and 15%, respectively.

- Despite disease progression, behavioral symptoms like agitation, irritability, apathy and nighttime behaviors in people living with dementia improved by 22%.

- Depressive symptoms experienced by individuals living with the disease were reduced by 34%.

Cost benefits of the program

An external evaluator compared utilization and cost outcomes and determined that over the course of 3 1/2 years, participants in UCLA’s program had lower total Medicare costs of care ($2,404 per year) relative to those receiving usual care.

In addition to cost savings for individuals and their families, the ADC program reports several financial benefits for health systems, including:

- Hospitalizations: 12% reduction

- ED visits: 20% reduction

- ICU stays: 21% reduction

- Hospital days: 26% reduction

- Hospice in last six months: 60% increase

- Nursing home placement: 40% reduction

UCLA finds that a care program following the ADC model may be able to pay for itself depending on local labor costs, comprehensiveness of billing and local overhead applied to clinical revenue.

To learn more or to contact UCLA about training and replication of the program, visit the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program website.

Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative

A model of care that incorporates person-centered dementia care into a broader framework for the care of older adults.

About the initiative

Age-Friendly Health Systems is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Catholic Health Association of the United States (CHA). Together in 2017, they set a bold vision to build a social movement so all care with older adults is age-friendly care, that:

- Follows an essential set of evidence-based practices.

- Causes no harm.

- Aligns with “What Matters” to the older adult and their family caregivers.

The Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative defines “What Matters” as knowing and aligning care with each older adult’s specific health outcome goals and care preferences including, but not limited to, end-of-life care, and across settings of care.

- Health outcome goals relate to the values and activities that matter most to an individual, help motivate the individual to sustain and improve health, and could be impacted by a decline in health — for example, babysitting a grandchild, walking with friends in the morning, or volunteering in the community. When identified in a specific, actionable, and reliable manner, patients’ health outcome goals can guide decision making.

- Care preferences include the health care activities (e.g., medications, self-management tasks, health care visits, testing, and procedures) that patients are willing and able (or not willing or able) to do or receive.

The 4Ms framework of an Age-Friendly Health System

The 4Ms are not a program, but a framework to guide how care is provided to older adults through every interaction with a health system’s care and services. The 4Ms — What Matters, Medication, Mentation, and Mobility — make the complex care of older adults more manageable because they:

- Identify the core issues that should drive all care and decision making with the care of older adults.

- Organize care and focus on the older adult’s wellness and strengths rather than solely on disease.

- Are relevant regardless of an older adult’s individual disease(s).

- Apply regardless of the number of functional problems an older adult may have, or that person’s cultural, ethnic or religious background.

The 4Ms framework is most effective when all 4Ms are implemented together and are practiced reliably (i.e., for all older adults, in all settings and across settings, in every interaction).

The intention is to incorporate the 4Ms into existing care — rather than layering them on top —to organize the efficient delivery of effective care. This is achieved primarily through redeploying existing health system resources. Many health systems have found they already provide care aligned with one or more of the 4Ms for many of their older adult patients. Much of the effort, then, is to incorporate the other elements and organize care so all 4Ms guide every encounter with an older adult and their family caregivers.

Cost benefits of the initiative

The business case for becoming an Age-Friendly Health System focuses on its financial returns and is stronger when:

- The financial benefits are captured by the health system that is making the investment.

- Utilization and associated expenses of “usual” care are especially burdensome.

- The health system is effective in mitigating those costs.

- The added expense of becoming age-friendly is lower.

See the IHI report, The Business Case for Becoming an Age-Friendly Health System , for guidance on how to make the business case for your health system.

To learn more or to contact IHI about joining the initiative, visit the IHI Age-Friendly Health Systems website.

Health Systems and Medical Professionals Menu

- Alzheimer’s Association Innovation Roundtable (AAIR)

- Prescribing Lecanemab

- Cognitive Screening and Assessment

- Dementia Care Navigation Guiding Principles

- Dementia Care Navigation Roundtable

- Differential Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease

- Differential Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Differential Diagnosis of Lewy Body Dementia

- Differential Diagnosis of Frontotemporal Dementia

- Differential Diagnosis of Huntington's Disease

- Differential Diagnosis of Korsakoff Syndrome

- Differential Diagnosis of Mixed Dementia

- Differential Diagnosis of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Differential Diagnosis of Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Differential Diagnosis of Vascular Dementia

- Disclosure of Diagnosis

- Advanced Imaging and Biomarkers

- Care Planning Visit

- Advanced Care Planning

- Alzheimer's Network (ALZ-NET)

- Guidelines Index

- Clinical Trials Recruiting

- Downloadable Resources for Patients and Caregivers

- I Have Alzheimer's

- Clinical Trials

- Instructional Videos

- Cognitive Assessment Tools

- ISTAART Membership

- Alzheimer's & Dementia Journal

- Continuing Education on Alzheimer's and Dementia

- The Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care ECHO® Program for Health Systems and Medical Professionals

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Case studies

The below case studies are taken from the document ‘ Good care planning guide for dementia ‘

- Core elements of a care plan

- An example person centred care plan

- A care plan: system compatibility and configuration

- An example process for dementia annual review template

- Example QOF annual review templates

- A framework for annual review

- An example best practice care plan template

- An example dementia annual review template

- My advance care plan

- Caring for me: Advance care planning

- Caring for me: Advanced care plan – Supporting information for patients and their families/carers

- Planning for your future – Advance care planning

- My plan for making the most of my life

- Staying well check tool

- Sharing care plans

Best Practice Repository case studies

- Dementia Awareness Training

- Diagnosing Well: Stockton

- Diagnosing Well: Enfield Memory Service

- Improving harm from falls as part of the Patient safety initiative

- Diagnosing Well in Carlisle

- Diagnosing Well in Newcastle

- Diagnosing Well in Northallerton – Assessment and diagnosis in one day

- Dementia care improvements

- A Triangle of Care – Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care

- Getting Evidence into Admiral Nurse Services (GEANS)

- GEANS – ‘Getting Evidence into Admiral Nursing Services’

- Improving outcomes for people with dementia during a hospital stay

- The Dementia Assessment and Intervention: Striving for Innovative and Evidence-based Services (DAISIES

- A gesture speaks a thousand words

- Aging care commissioning strategy

- Factors associated with carer quality of life of people with dementia: A systematic review of non-interventional studies

- Dementia Friendly Hospices – Embedding a sustainable model to develop the skills, knowledge and confidence of Hospice staff across Yorkshire and the Humber

- Talking ‘Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR)’

Additional case studies

- Medications for treating people with dementia – summary of evidence on cost-effectiveness

- Dementia care mapping – Evidence Review

- Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) – summary of evidence on cost-effectiveness

- A coping programme for family carers of people with dementia – summary of evidence on cost-effectiveness

- End of Life Care Service for People with Dementia Living in Care Homes in Walsall

Making Hospitals More Dementia Friendly: Case Studies

The following is an excerpt from the “Planning for your hospital” section of the Dementia Friendly Hospital Toolkit developed by CARE and clinical and research faculty at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Nursing.

As we developed CARE’s Dementia Friendly Hospital Toolkit, we learned from two Wisconsin hospitals with their own dementia friendly initiatives: the W.S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital in Madison and Stoughton Hospital in Stoughton. One of the hospitals that piloted our training materials, Fort HealthCare in Fort Atkinson, shared how they were launching their dementia friendly initiative using our toolkit.

Getting input from others

“We need to involve more than just nursing,” realized Lisa Rudolph, MSN, RN, the Education Services Manager at Fort HealthCare, when she was asked to lead dementia friendly planning. “If you don’t get staff involved, then that buy-in is not there. I wanted to make a task force and make it interdisciplinary.”

Fort HealthCare’s interdisciplinary task force includes a wide range of staff, from a nurse practitioner to volunteer services to radiology. They began by educating themselves on dementia and will help develop the hospital’s training plan. Rudolph recruited task force members by “reaching out to leadership and saying, ‘I would like some people from your department.’ I also reached out more broadly and said, ‘If you have a loved one, or some interest, or a personal connection with dementia, then I want you to be part of this, too.’”

Don’t forget key stakeholders outside of hospital staff and leadership. “It’s really important to get patient and family perspectives,” said Mary Wyman, PhD, a clinical psychologist and research investigator at W.S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital. “We need to hear those voices, though it can be hard.”

Connecting with community organizations

Fort HealthCare’s community connections have provided dementia education to staff. “I reached out to our ADRC [Aging and Disability Resource Center] dementia care specialist,” said Lisa Rudolph. “She did a training with our task force members. It was interactive and an eye-opening experience for us.”

Stoughton Hospital is part of Stoughton’s dementia friendly community coalition. Heather Kleinbrook, BSN, RN, PMH-C, CDP, the Department of Nursing’s Inpatient Services Manager, also chairs the community coalition.

“A lot of what we do is education, getting businesses engaged and trained in how to be dementia friendly,” Kleinbrook said. “We provide education at the hospital. We started a memory café which we hold at the hospital monthly. We’re doing music and memory with the library.” The hospital’s community involvement increases awareness of their dementia friendly commitment and offers meaningful volunteer opportunities to staff.

The Madison VA participates in a regional coalition of dementia friendly groups, organized by the county dementia care specialist. “It’s a good way to stay plugged into what’s happening,” said Mary Wyman. “It’s inspiring. So many creative ideas come from these groups getting together. It helps us be more effective.”

Advice for people launching dementia friendly hospital initiatives

“It’s important to have support from administration from the get-go,” said Lisa Rudolph at Fort HealthCare. “Also think about setting some dollars aside for equipment or training. This isn’t a one and done. Think about onboarding new employees and having staff practice some of these skills every month or so.”

“There are so many places to improve the experience and quality of care for people living with dementia,” said Mary Wyman with the Madison VA. “Start with one bite-sized project. Also think about how dementia friendly improvements can align with other goals of the organization. For example, we made big wayfinding changes early on. There were other things we could have done, but people had for years been raising concerns about how confusing it was to get around our facility. So we were able to partner with a larger group and build momentum because we had a shared goal of improving wayfinding.”

Stoughton Hospital’s Heather Kleinbrook stressed the importance of finding staff “who are passionate and have a story to tell. They will help get others on your side. All of my administrative team had stories. They had a mother or father or grandparents who were living with dementia. When people have a passion, it’s amazing what you can do.”

Case studies

These three case studies help you to consider different situations that people with dementia face. They are:

- Raj , a 52 year old with a job and family, who has early onset dementia

- Bob and Edith , an older married couple who both have dementia and are struggling to cope, along with their family

- Joan , an older woman, who lives alone and has just been diagnosed with dementia

Each case study contains:

- A vignette setting out the situation

- An ecogram showing who is involved

- An assessment which gives essential information about what is happening and the social worker’s conclusion

- A care and support plan which says what actions will be taken to achieve outcomes

You can use the practice guidance to think about how you would respond in these situations.

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

For care 0203 728 7577

For jobs 0203 728 7570

Looking for care? 0203 728 7577

Looking for a job? 0203 728 7570

Case Study: Dementia Care

See how we help Steve to live well with dementia in his own home

Case Study: Supporting Steve with dementia home care

Our vascular dementia client.

Steve is 88 years old and living with vascular dementia. He lives with his wife Anne who was his primary carer. Steve’s dementia meant that he was highly anxious, easily agitated and dependent on Anne. He would become paranoid and aggressive if she left his sight.

Steve had enjoyed a successful career in business, in the military and as a civilian pilot. Now the frustration he felt was showing itself as aggressive outbursts. He had been prescribed antipsychotic medication which was negatively affecting his physical and mental well being but sadly not making a difference to his behavioural symptoms. His care was putting an immense burden on his wife Anne.

When Anne’s daughter Carol contacted The Good Care Group, the challenge was to find a way of providing care that was acceptable to Steve, did not threaten his self-esteem or cause him undue agitation.

Our dementia home care service

Using the SPECAL® method*, we found Steve could still access many positive memories of his time as a pilot. When we referenced aeroplanes or flying, he would swing his arm in a wide arc and say with pride ‘I flew around the world, you know’.

Through accessing and cueing positive past memories we found we could allay Steve’s fears. Steve’s behaviour became calmer and he was less prone to fear, paranoia and aggressive outbursts.

However, he would still get upset and angry if he felt Anne had gone somewhere without him. Anne wished to take a break and the challenge was to facilitate this without causing Steve excessive anxiety.

Again, his dementia care team worked with Steve and his family to uncover old memories and found that Anne had owned and run a small florist. Steve was very proud of this but would not have been involved in the day to day running of the business. The next time Steve asked where Anne was, we used a phrase – ‘sorting out a problem at the shop’ – which was familiar to Steve, and which reassured him that Anne was tied up elsewhere without making him feel that he should be there with her. Once the twin themes of flying and Anne’s need to solve problems at the florist had been established, we managed to facilitate a holiday for Anne and her daughter without causing distress to Steve.

Our success

Steve continues to live with dementia in the comfort of his own home. He is off of his anti-psychotic medication and outbursts are rare events. The care and support offered by The Good Care Group has given back independence to Anne who can again be his loving wife, not solely his carer, and allow her to take days out and the occasional holiday abroad. For more information about the SPECAL® method, please visit www.contenteddementiatrust.org

See The Types of Home Care We Offer For Dementia

“The Good Care Group helped me to make time for myself so I can give Steve the love and care he deserves. The SPECAL approach really worked for Steve – his own doctor said nothing could be done and that the only option was a life on medication.”

Talk to us about your dementia care needs.

Our friendly and experienced team is here to help you and your family make sense of the options available to you. Call us today – we will help you every step of the way.

0203 728 7577

Enquiry Form

Enquiry – Floating Button

Enquire now

Dementia Caregiver Studies

Testing ways to minimize stress and promote health in family caregivers of people with dementia.

Welcome to the Dementia Caregiver Studies of Case Western Reserve University. For over a decade, we have learned from caregivers and for caregivers. Led by Dr. Jaclene Zauszniewski, an internationally recognized nurse-scientist and Distinguished Faculty Researcher Award recipient of CWRU, we provide opportunities for family caregivers to participate in a number of research projects that all share a common goal: helping caregivers to better manage stress and stay healthy.

Our current projects, both funded by the National Institutes of Health, are focused on adult family members of persons experiencing a progressive memory problem or dementia such as Alzheimer’s Disease. Based on both her research and her personal experience, Dr. Zauszniewski recognized that caregiving includes family members who provide support and supervision at home, those who partner with a care facility where an impaired family member now lives, and even bereaved former caregivers who have recently lost their loved one. All three of these types of family caregivers are welcome to participate in our research projects.

Study participants will learn one of a number of stress management methods that may help to better manage caregiver stress and promote a healthy body and mind. Participants complete 2 or 3 interviews during the course of the next year to assess whether the strategies were helpful. In addition to the possible benefit of the method learned, and the satisfaction of helping other caregivers, participants are compensated for their time.

We are enrolling new participants and invite you to fill out the form in the Contact Us section below to see if you are eligible to participate.

You can also visit the study's Facebook page here .

- Principal Investigator

- Faculty Associates

- Team Members

Jaclene Zauszniewski, PhD, RN-BC, FAAN , is the Kate Hanna Harvey Professor in Community Health Nursing. "Dr. Z" is known for her pioneering work on personal and social resourcefulness as it relates to managing stress, depression and chronic illness. As a psychiatric nurse scientist, Dr. Z has conducted five NIH-funded studies and has mentored countless students in the PhD nursing program at Case Western Reserve University.

Christopher Burant , PhD, MACTM, FGSA; Co-Investigator

Evanne Juratovac , PhD, RN, GCNS-BC, Intervention Supervisor

Eva Kahana , PhD, CPMA; Co-Investigator

Martha Sajatovic , MD, Co-Investigator

Evelina DiFranco, MPH Research Associate Email: [email protected]

Barbara Boveington-Molter, MS Research Assistant Email: [email protected]

Kari Colón-Zimmermann, MA Research Assistant Email: [email protected]

Catherine Larsen, BS Research Assistant Email: [email protected]

Hangying She, RN; PhD student Data Coordinator Email: [email protected]

John S. Sweetko, PhD, RN, CPEN, CNE, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar Research Associate Email: [email protected]

Rayhanah Almutairi, PhD student, MSN, AGPCNP-BC Graduate Research Assistant

Teaching Resourcefulness to Women Caregivers of Elders with Dementia

Principle Investigator: Jaclene Zauzsniewski

Co-Investigators: Diana Morris , Amy Zhang

The goal of this R21 Exploratory Research Grant was to pilot test an adapted intervention that teaches personal and social resourcefulness skills to women caregivers of elders with dementia. This pilot study provided qualitative and quantitative data for examining the six parameters of Resourcefulness Training© (RT) that were believed to be essential for strengthening the scientific rationale for a subsequent full scale randomized controlled trial. Within the context of a modified partially randomized preference trial with 138 women dementia caregivers, the necessity, acceptability, feasibility, fidelity, safety , and effectiveness of two innovative methods of RT were investigated. The results suggested a substantial need for RT in women caregivers of elders with dementia and support moving forward with testing RT effectiveness for reducing caregiver stress and depressive symptoms.

- Dementia care case studies

Who we're supporting with specialist dementia care at home

Seeing how dementia is affecting someone close to you can be distressing. We’ve been supporting people with dementia nationwide for almost 30 years. Read some of the stories below from the families we’ve helped.

Whether you’re looking for a visiting care service or more permanent live-in care support , our care is completely flexible to suit yours and your family’s needs.

To learn more about how we can provide dementia care in your own home, call our friendly care team today.

Dorothy’s story – dementia case study

How home care helps dorothy live the life she wants.

Dorothy says, “There really is no place like home, and with Magda’s support I am able to keep in touch with all of my friends and neighbours. We visit church every week for the Sunday morning service, I can visit the shops and I also take part in a local knitting group. This really is one of the greatest joys of staying in my own home around people I know.”

By helping her to do the activities that mean most, Magda has made such a difference in Dorothy’s life. An experienced carer with plenty of care knowledge, what matters most to Magda is that Dorothy is happy.

Dorothy says, “Live-in care means friendship, a sense of security and feeling comfortable in my own home. Having previously spent a brief but unhappy period of time in a care home, I am able to recognise how perfect my situation is now. I feel very lucky and comfortable; I have a true friend. Magda is going nowhere! I want this to continue forever.”

Joan’s story – dementia case study

Switching from a care home to live-in care

For the families that we support, deciding that their loved one needs additional support can be a difficult choice to make. For Joan, whose husband, Peter, had vascular dementia, having a live-in carer helped to keep her family together.

After feeling let down by a care home, Joan came across our 24-hour care support. After talking through our services and her family’s needs, we provided her with profiles of some of our carers. Lazlo’s profile stood out immediately.

Lazlo and Peter built a close friendship and other members of Joan’s family also loved having Lazlo around. As Peter neared the end of his life, Lazlo helped to make sure he was as comfortable as possible. He also worked closely with other healthcare professionals involved in Peter’s care, and helped his loved ones in any way he could.

Sue’s story – dementia case study

A daughter’s peace of mind.

What matters most to the families we support is that their loved one is safe and comfortable. When Sue needed some more support for her mother, Barbara, she decided that a live-in carer would be the best option.

Barbara’s carer, Rosemary, quickly became part of the family. She cooks Barbara’s favourite meals, tends to her personal care needs, and even listens to her stories about her adventures in the Pembrokeshire countryside, where they have also taken short breaks together.

Sue says, “Live-in care has made such a difference. [Mum] is so much more contented, she doesn’t have to worry – and neither do I – about somebody different coming in.”

Andy's story – dementia case study

Expert care for a declining condition.

Andy’s mother was living with dementia and her condition suddenly started to worsen. The daycare she was receiving couldn’t stretch to overnight support, and Andy and his siblings all lived an hour or more away.

On the recommendation of a visiting nurse, Andy contacted Helping Hands. “Very quickly things started falling into place,” he said. “I never felt that I was talking to anyone other than professionals, and yet it was done with an empathy which was greatly appreciated.”

Andy explained how we found the right carer for his mum. “Mum’s needs were expertly assessed without coming across as intrusive. We were also invited to provide our thoughts as to the sort of person who would get on best with Mum, the village environment and the friends with whom she would become acquainted.”

After three months of live-in care, during which time Andy said that his mother’s decline “seemed to have slowed”, the family made the decision to move her to a care home so she would be closer to them.

Andy described their Helping Hands carer saying, “I have absolutely no doubt that on this member of staff’s ‘watch’ Mum had a great time… We would often call to speak to Mum and simply had to bail out because Mum and them were giggling too much!

“I have to say I don’t know where we would have been over these three months without their dedication and support,” added Andy. “Thanks to all involved in my mother’s care.”

Other people are interested in...

We’re here seven days a week to talk through your home care needs and find the best option for you. Call 03300376958 or request a callback and we will call you.

Live in care

Quality live-in care at home, across England and Wales

What makes our carers and support workers so special

Testimonials

What our customers say about our home care

Page reviewed by Deanna Lane , Senior Clinical Lead on March 24, 2022

Find your perfect carer

Find the right affordable care for you

- After Hospital Care

- Comfort Care

- Community Care

- Comprehensive Home Care Packages for the Elderly

- Convalescent Care

- Critical Care

- Disability Care

- Domestic Care

- Hire a Carer

- Hospice care at home

- Intensive Care

- Intermediate Care

- Long term care

- Medication Management

- Personal care

- Postoperative Care

- Preventative Care

- Reablement Care

- Supported Living

- The Advantages of Home Care

- What is home care?

- Domiciliary care

- Loneliness is a guest nobody wants this Christmas

- Respite care

- How Are Parkinson’s And Dementia Related?

- How Dementia Affects Day to Day Living

- How Is Dementia Diagnosed

- Types of dementia

- What Does Dementia Feel Like?

- What Is Dementia Care Mapping?

- What is dementia care?

- Dementia Life Story Book

- Dementia care questions

- Our dementia experts

- Live in care for dementia

- Dementia care guide

- Diet for dementia

- Overnight care

- Palliative care

- Elderly care

- Support for younger people

- Condition-led care

- End of life care

- Housekeeping services

- Emergency home care

- Mobility aids and home adaptations

- Carer supported holidays

- Home Care FAQs

- What Is Home Help?

- Alternative to care homes

- Preparing For Home Care

- What Is A Home Carer?

- Difficult conversations: How to start a conversation about care

- Emotional well-being

- Our independent life

- Home care for Christmas and New Year

Guide to dementia home care

Looking for local care?

Friendly, expert care is closer than you think

Show in maps

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2021

The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research: findings of a systematic qualitative review

- Tim G. Götzelmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6998-0850 1 na1 ,

- Daniel Strech 2 &

- Hannes Kahrass 1 na1

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 32 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

9812 Accesses

14 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

When including participants with dementia in research, various ethical issues arise. At present, there are only a few existing dementia-specific research guidelines (Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use in Clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment Alzheimer’s disease (Internet). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-investigation-medicines-treatment-alzheimers-disease ; Food and Drug Administration, Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industry [Internet]. http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/alzheimers-disease-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industy ), necessitating a more systematic and comprehensive approach to this topic to help researchers and stakeholders address dementia-specific ethical issues in research. A systematic literature review provides information on the ethical issues in dementia-related research and might therefore serve as a basis to improve the ethical conduct of this research. This systematic review aims to provide a broad and unbiased overview of ethical issues in dementia research by reviewing, analysing, and coding the latest literature on the topic.

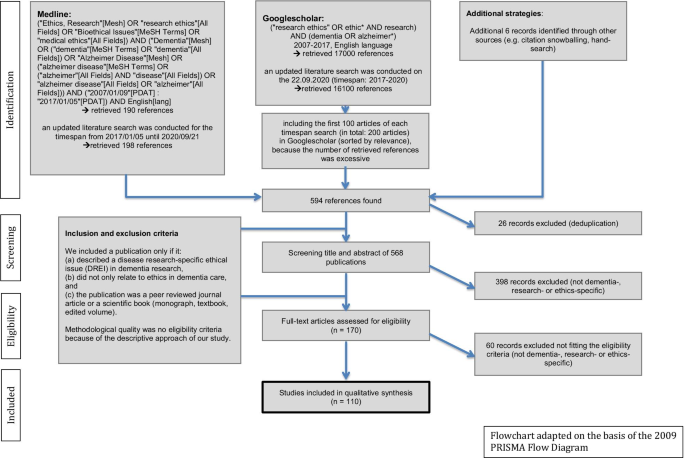

We conducted a systematic review in PubMed and Google Scholar (publications in English between 2007 and 2020, no restrictions on the type of publication) of literature on research ethics in dementia research. Ethical issues in research were identified by qualitative text analysis and normative analysis.

The literature review retrieved 110 references that together mentioned 105 ethical issues in dementia research. This set of ethical issues was structured into a matrix based on the eight major principles from a pre-existing framework on biomedical ethics (Emanuel et al. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. in The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008). Consequently, subcategories were created and further categorized into dementia stages and study phases.

Conclusions

The systematically derived matrix helps raise awareness and understanding of the complex topic of ethical issues in dementia research. The matrix can be used as a basis for researchers, policy makers and other stakeholders when planning, conducting and monitoring research, making decisions on the legal background of the topic, and creating research practice guidelines.

Peer Review reports

Dementia prevalence rates are estimated to quadruple by 2050 [ 1 , 2 ]. Though such forecasts must be interpreted carefully, the global community is likely to face several challenges concerning the individual and familial burdens, societal and political consequences, and economic impact of dementia. With the growing size of the population with dementia, the costs of care are expected to increase in the near future [ 1 ].

The need for research on risk factors [ 2 ], palliative care, and reducing individual psychological burden is therefore of global importance. Research conducted with participants living with dementia raises important ethical questions, such as how to protect cognitively impaired persons against exploitation, how to design informed consent (IC) procedures with proxies, how to disclose risk-factors for dementia given the lack of evidence for their reliability, and how to apply risk–benefit considerations in such cases [ 3 ].

Out of fear of not being able to fulfil the ethical obligations required when conducting research with incapacitated persons, some might suggest the overall exclusion of cognitively impaired persons, or even of all individuals affected by dementia, from research. This caution may lead to the abandonment of meaningful research on dementia and would exclude dementia research from medical progress, leaving affected persons and their relatives orphaned.

Several guidelines [ 4 , 5 ] provide some orientation as to what should be considered to ensure that research on humans is ethical. These guidelines cover the entire research process from planning, conducting, and monitoring the trial to post-trial. Furthermore, they claim specific protection for vulnerable groups and individuals but are not meant to provide details on what that means for dementia research or other patient groups. Many authors have discussed the ethical challenges of dementia research [ 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. These publications are characterized by a rather narrow focus on certain issues, e.g., on alternatives for obtaining IC [ 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] or genetic testing [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Some even use a combination of a systematic and a narrative review approach, with the emphasis on identifying differences in the ways ethical issues are addressed [ 21 ]; however, a review of the full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research is still missing in the current literature.

In our systematic review, we therefore aimed to identify the full and unbiased spectrum of research on ethical issues in dementia as discussed in the literature.

Literature search and selection

Three strategies were applied to the literature search: PubMed (database), Google scholar and hand searching methods. We included a publication only if it: (a) described a disease research-specific ethical issue (DREI) in dementia research, (b) did not only relate to ethics in dementia care, and (c) the publication was a peer reviewed journal article or a scientific book (monograph, textbook, edited volume). Methodological quality was no eligibility criteria because of the descriptive approach of our study.

The Flowchart (Fig. 1 ) presents further details on the search algorithm and the eligibility criteria. This approach has already been applied before and can be read in detail elsewhere [ 22 ]. For reference management, we used the programme “Zotero”.

Literature search algorithm adapted on the basis of the 2009 “PRISMA Flow Diagram”

Definition and typology of dementia research-specific ethical issues (DREIs)

For the definition of DREI, we referred to the ethical theory of principlism. Emanuel et al. suggest eight principles that make clinical research ethical: respect for participants, independent review, fair participant selection/recruiting, favourable risk–benefit ratio, social value, scientific validity, collaborative partnership and IC [ 4 ]. These principles represent guiding norms that must be followed in a particular case unless there is a conflict with another obligation that is of equal or greater weight, e.g., alternatives to obtaining IC in special groups or situations. These principles provide only general ethical orientations that require further detail to give guidance in concrete cases. Thus, when applied, the principles must be specified and—if they conflict—balanced against one another.

There are two types of ethical issues that could arise: (a) inadequate consideration of one or more principles (e.g., “risk of insufficiently informing IRBs [institutional review boards] about adequate steps taken to fulfil the ethical obligations of dementia research”) or (b) conflicts between two or more principles (e.g., “challenge of balancing divergent statements in ARD [advance research directive] against current dementia patient wishes or proxy decisions (now vs. then)”). The terms "risk" (a) and "challenge" (b) used in the following refer to this conceptual consideration.

Analysis and synthesis of DREIs

For analysis, we used thematic content analysis [ 23 ] for all 110 included references. To identify and clarify potential ambiguities during content analysis as early as possible a first purposively sampled cluster of references (n = 10) was coded by two reviewers (TG, HK) independently. Another sample of detailed references (n = 9) was coded by one reviewer (TG) only. To capture as many ethical issues as possible this first cluster purposively included more detailed and comprehensive publications. The identified issues were then compared and grouped into the eight principles framework [ 4 ] in a consensus process using a programme for qualitative data analysis (“MAXQDA”). Because the consensus process revealed sufficient clarity for how to deal with ambiguous codings the remaining references (n = 45) were randomly split in half and analysed by one author (HK or TG) only. We updated the search in September 2020 and included another sample of 46 studies. These studies were coded by one author (TG). If further ambiguities during coding occurred they were discussed and clarified in the team.

For synthesis, we used a mixed deductive-inductive approach that takes into account the eight principles and the descriptions from the primary literature. We introduced subcategories if we found it reasonable to do so (for example if the number of DREIs was high). Finally, we used dementia stage and study phase to further categorize the identified issues (see Table 1 ). While we started with the established eight principles for clinical research ethics as a coding framework, our coding procedure was open for DREIs which could not be grouped under one of the eight principles.

References and journals

The literature search in PubMed and Google Scholar revealed a total set of 594 references, 110 of which were ultimately included in the analysis, published between 2007 and 2020 in 64 different journals. For more details, see the flowchart (Fig. 1 ).

Spectrum of dementia research ethical issues (DREIs)

The analysis of the 110 references revealed 105 DREIs. All identified issues could be grouped under one of the eight principles for ethical research, some having far more DREIs than others. In detail, “respect for participants” (n = 11 DREIs), “independent review” (n = 3), “fair participant selection/recruiting” (n = 5), “favourable risk–benefit ratio” (n = 16, 3 subcategories), “social value” (n = 2), “scientific validity” (n = 20, 5 subcategories), “collaborative partnership” (n = 5) and “informed consent (IC)” (n = 43, 12 subcategories). In the course of data analysis, we subsequently found fewer new codes, and the last 10 analysed papers raised no new issues. Thus, we appear to have achieved thematic saturation for the spectrum at least for the level of major groups and first-level subgroups. We updated the search in September 2020 which lead to the analysis of 46 references from the years 2017 until 2020. During the process of literature analysis, only one new subcategory was found in a paper from 2018 [ 24 ], hereafter no new sub-categories have been identified (for the years of 2019 and 2020).

All identified DREIs and subcategories are presented in Table 1 . This table also contains the categorization according to the dementia stage (based on the NIA-AA-2018-Framework) [ 25 ] and the phase of the research for each issue, symbolized by superscript numbers or characters. Additionally, the 105 DREIs are presented in separate tables for each category of dementia stage (Additional file 1 ) and the phase of the research (Additional file 2 ). A full list of the found issues together with the accompanying original text examples as well as the list of all references that were analysed during our systematic review are available in Additional file 3 : Table S3. The above listed tables are available at the supplemental data.

We used the nomenclature of the NIA-AA-2018-framework (“cognitively impaired”, “mild cognitive impairment (MCI)” and “dementia”) [ 25 ] for the first three categories in our dementia stages categorization. Most DREIs were related to more than one dementia stage (category IV, n = 60, Table 1 ). DREIs related to “cognitively unimpaired” (category I, n = 7) centre around the principle of favourable risk–benefit ratio, especially dealing with the sub-categories “determining risk adequately” and “considering risk adequately”, and the principle of respect for participants. No issues were found to fit “mild cognitive impairment” exclusively (category II), where people with dementia are not yet incapacitated. In category III = dementia (n = 11), issues mostly referred to “IC”, especially addressing the sub-category “proxy consent”. Finally, 27 DREIs could not be classified in that split spectrum.

Concerning the categorization due to study phase , we used a timeline approach in naming the different study phases (I = recruiting/pre-trial, II = conduction phase, III = post-trial, IV = general). For DREIs related to specific study phases, again, most DREIs were found to be of overarching relevance (category D, n = 45). In the recruiting/pre-trial phase, DREIs arise within “independent review”, “fair participant selection/recruiting”, “scientific validity”, and “informed consent” (category A, n = 32). While conducting the study (category B, n = 9), DREIs are related to “drop-outs” that endanger scientific validity and the “ongoing assessment” within the principle of informed consent. The post-trial phase is mostly concerned with the principle of respect for participants, communicating the results to the participants and the scientific community (“poor reporting quality”) and adequate follow-up of the volunteers (category C, n = 6). Thirteen issues could not be classified under the topic of study phase .

Specification of general principles for ethical dementia research

All principles for ethical research [ 4 ] were specified in the analysed literature. The references to general principles, such as “IC”, are rather implicit; however, authors elaborate on how the characteristics of dementia lead to specific ethical challenges, e.g., “However, a special ethical issue with regard to longitudinal studies that end in participants’ death is that participants are competent when first recruited, but have a significant likelihood of becoming incompetent while they are study subjects. […] [T]he gradual loss of the capacity to consent […] creates challenges for informed consent, the ethical bedrock of research with human subjects. […][Here], it may make sense to re-evaluate consent capacity […] at several intervals during the study" [ 6 ].

From this statement, the following DREI was paraphrased: “Risk that IC at the beginning of a dementia study alone is insufficient because of cognitive decline of participants”. This DREI is of general relevance for all dementia stages but has particular relevance to the study phase “recruiting/pre-trial”. The full spectrum of issues, including original text examples and all references, is presented in the online supplement (see Additional file 3 ).

Issues which were mentioned the most, are, for example, “Risk of excluding relevant subgroups, e.g. inhabitants of nursing homes, those lacking a proxy/spouse or patients with other psychiatric diseases, from dementia research” (n = 25 papers) and “Risk of excluding participants from research due to lack of capacity to consent” (n = 23). Examples of rarely mentioned DREI are “Risk that dementia patients experiencing stigmatization will lead to low follow-up rates or study withdrawal” (n = 1), “Risk of therapeutic misconception being higher in participants with MCI or mild dementia” (n = 1) and “Risk of RECs [research ethics committees] weighing opinions of physicians (protecting the participant) over patients’ willingness to participate and over nurse counsellors’ opinions” (n = 1).

Several DREIs were only addressed in an implicit manner; for example, “Risk that varying international regulations are a burden for international dementia research” is based on the following quotation: “However, only in Germany and Italy is the system of proxy determined by the courts—a procedure which is not necessarily required for the recognition of a proxy in other member states” [ 26 ].

This systematic literature review identified and synthesized the full spectrum of 105 ethical issues in dementia research (DREIs) based on 110 references published between 2007 and 2020 in 64 different journals.

Many ethical issues involved “IC” (n = 11) in incapacitated participants and “risk-information disclosure” (n = 8). However, this review shows that there are many more DREIs to consider when planning, reviewing, conducting, or monitoring research with this vulnerable group. We assume that the results will be of interest to different groups—clinical experts, researchers, policy makers, REC-members, lawyers, patient-organization representatives or even affected persons themselves—and that the different stakeholders will read and use the results differently.

Our review lists several ethical issues grouped under eight broadly established ethical principles for clinical research. These principles and the principlism approach in general are correlative to basic human rights [ 26 ]. The eight principles are not focused on capacity-based approaches but include approaches to express the right to participate in research via, for examples, advance directives. We would therefore argue, in line with many other ethical analyses based on a principlism approach, that human rights related ethical issues in dementia research are captured directly and indirectly by the many ethical issues addressed in our list of issues. The same applies to other overarching normative concepts such as “avoiding exploitation”. No specified ethical issue in our list mentions the risk of exploitation directly but more or less all specific ethical issues address this risk indirectly. Likewise, the wording “human rights” did not appear explicitly in the literature we analyzed.

Those looking for support or guidance on how to seek ethically appropriate dementia research might prefer detailed descriptions of very specific challenges. Articles such as “Seeking Assent and Respecting Dissent in Dementia Research” by Black et al. [ 9 ] serve this purpose. However, these publications often focus on particular aspects and do not aim to provide a detailed and systematic overview. Further, one also has to do thorough searching and read a large volume of material (we screened n = 594 and finally included n = 110 references) to be familiar with all the aspects discussed in the literature. In contrast to literature addressing very specific DREIs, there are also broad, theoretical frameworks for research ethics, such as that of Emanuel et al. [ 4 ]. However, if capacity building for ethics in dementia research is primarily informed by such general frameworks, it might overlook issues that only become apparent when specifying practice-related tasks. Our review is intended to bridge detailed specifications with a comprehensive and structured presentation of the DREIs at stake.

We illustrate the bridging character of our study by comparing one benchmark for the IC principle originating from Emanuel et al.’s framework [ 4 ] with one issue on our spectrum grouped under “IC” in the subcategory “proxy consent”. The benchmark is “Are there appropriate plans in place for obtaining permission from legally authorized representatives for individuals unable to consent for themselves?” [ 4 ]. A researcher with a specific trial in mind would, in order to conduct morally sound research, perhaps refer to that benchmark in a case where they plans to start a trial on incapacitated patients suffering from dementia. This person would then fulfil that benchmark by making it possible for legal representatives of the patients to fill out the IC document in place of the incapacitated participant. Thus, they would fulfil the benchmark and might not think about more specific ethical problems that might arise when one looks into the literature describing DREI. One such example is this quote stemming from an article on dementia research ethics: “Proxy consent, already an issue of debate in traditional research, was considered more problematic in genetic research, where children share the same genetic traits as their parents. On the one hand, this might be a motivation for the affected parent to participate in a research study to help their children. On the other hand, it was questioned that to what extent children still are able to make a decision in the best interest of their parents because they have an interest themselves. The more genetic research will be carried out, the higher the chance on a disease modifying or preventive therapy for them and their children” [ 14 ].

In that case, and if the researcher had a plan to conduct research in this field of genetic dementia research, the simple fulfilment of the abovementioned benchmark would be insufficient for the goal of morally acceptable research. The mentioned quotation informed the creation of the DREI “Risk of not considering that proxies have major self interest in dementia research, e.g., because they have same genetic traits, which could influence their proxy decision, and their manipulative behaviour may be difficult to detect”.

As we compared topics between both rounds of the literature analysing process, we noticed, that some topics were newly introduced in the scientific literature, in particular “deep brain stimulation” issues in dementia research. Other categories or sub-categories like “social value”, “qualified personnel” and “informed consent document” were not further discussed in scientific literature.

In addition, we found more and more text examples for issues which before the year of 2017 were only mentioned once, e.g. “Risk of over diagnosis in asymptomatic persons, if the diagnosis is derived from the risk marker status, since their corresponding validity regarding the occurrence and course of a disease is (still) limited”, which now was mentioned in six papers.

Also, in the course of the analysis of the studies between 2017 and 2020 we found 22 new issues, among them 17 issues which were only mentioned by one paper showing the rapid emergence of new issues in the dementia research ethics field.

Capturing this full spectrum of DREIs can serve multiple purposes. First, it can raise awareness of the ethical issues arising in the context of dementia research, highlighting issues that may be underrepresented in the published literature through the side-by-side presentation in our matrix. Second, it can serve as the basis for information or training materials for researchers and caregivers. Third, it can form the basis for discussions on the importance and/or relevance of the different ethical issues. Fourth, because our spectrum does not rank the difficult DREIs in order of importance, third parties can use it as a basis for exactly that purpose. Fifth, developers of specific research guidelines or policy papers may use this spectrum as an entry point to that topic.

At this point, it is important to state that our spectrum remains strictly descriptive. The qualitative and normative interpretation is therefore left to others, e.g., researchers, policy-makers, patient organizations, funding partners and the community as a whole. Those interpretations could further help in developing stakeholder-oriented guidelines for conducting ethically sound research in dementia. The list of ethical issues as presented in this paper, however, cannot directly serve as a checklist for review purposes. More conceptual work is needed to translate the in-depth results of this systematic review into effective and efficient normative or procedural guidance. Finally, existing guidelines, policy papers or new research articles on the topic of DREIs can be screened for completeness [ 27 ].

To make the results of the review more concise and accessible, we prepared overviews sorted by stage and phase (available as an online supplement). This is particularly suitable for readers who have a certain focus, e.g., because they are currently planning a study with people in an early stage of dementia (see Additional file 1 ) or are looking for an overview of DREIs in the phase of conducting the study (see Additional file 2 ). These tables show that ethical issues are situation-sensitive, e.g., certain questions on informed consent only arise at a later stage of the disease, while questions of reporting the status of risk factors are only relevant in early stage (pre-symptomatic) patients.

One limitation of this systematic review is that the search was limited to PubMed and Google Scholar. We do not consider this an overly disadvantageous factor and consider the approach to be appropriate for the following reasons: First, our search resulted in the identification of literature from different fields, not only from the bioethics and medicine field but also spanning nursing research [ 28 , 29 ], nursing ethics [ 30 , 31 ], a narrative review [ 3 ] and even one systematic review [ 21 ]. This systematic review by West et al. covered mostly literature concerning IC, advance directives and the role of proxies or surrogates. Second, thematic saturation for the first-level categories was achieved after analysing 54 of the 64 papers that were included after the first literature search in these two data sources. For the updated literature search, which only found one new first-level category, thematic saturation was achieved after analysing 25 of the 46 papers. Third, former systematic reviews [ 32 , 33 ] in the bioethics field, which based their research on additional databanks such as EMBASE, CINAHL or Euroethics, found few additional references. Another limitation is that we only reviewed the literature from the last 14 years. However, we included two (systematic) reviews, which included literature dating back to 1982 [ 3 ] and back to 1995 [ 21 ]. We further assume that an important ethical issue that was mentioned 15 years ago and that is still relevant nowadays would be addressed in some more recent references again.

Further, we only included references in the English language. Some culturally sensitive DREI might be preferably discussed in the respective language, and our review might have missed those discussions. Last but not least, we only included peer-reviewed literature and thus did not consider grey literature such as guidelines from advocacy organizations involved with dementia research [ 34 , 35 ]. As a future project, we aim to employ the results of our review to analyse whether and how guidelines for dementia research mention the identified issues. For a similar approach see the results of a systematic review of ethical issues in dementia care [ 22 ] that was followed-up by a content analysis of clinical practice guidelines for dementia care [ 27 ].

The authors of this review have different scientific backgrounds: medicine/psychiatry, physiotherapy, public health, ethics and philosophy. However, all authors are currently involved neither in clinical research nor in health care for people with dementia. However, we do not consider this to be a weakness of the review, as we have included these perspectives in the literature considered, e.g., expert opinions [ 9 , 10 , 14 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], views of patients, caregivers and proxies [ 11 , 28 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ], papers focusing on legal and ethical guidelines [ 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 ], and the point of view of lay persons [ 13 ]. Our review found no papers on the opinions and views of relatives of people living with dementia. This might indicate the need for further research in that field.

This study has successfully shown that a systematic literature review leads to a wider spectrum of DREIs (n = 105) than other papers on the subject. The identified issues are specifications of eight general ethical principles for clinical research and could be categorized according to the dementia stage and study phase. Therefore, the spectrum can be used to raise awareness about the complexity of ethics in this field and can support different stakeholders in the implementation of ethically appropriate dementia research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Dementia research-specific ethical issue(s)

Informed consent

Institutional review board(s)

Advanced research directives

Tim Götzelmann

Hannes Kahrass

Mild cognitive impairment

Research ethics committee(s)

Daniel Strech

Randomized controlled trial(s)

European union

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

Mini-Mental State Examination

Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, Prince M, Winblad B, International AD. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):1–11.

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63–75.

Article Google Scholar

Johnson RA, Karlawish J. A review of ethical issues in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(10):1635–47.

Emanuel EJ, Grady CC, Crouch RA, Lie RK, Miller FG, Wendler DD. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. In: The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics. Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 123–35.

WMA - The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [Internet]. [Cited 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ .

Davis DS. Ethical issues in Alzheimer’s disease research involving human subjects. J Med Ethics. 2017; medethics—2016.

Sherratt C, Soteriou T, Evans S. Ethical issues in social research involving people with dementia. Dementia. 2007;6(4):463–79.

van der Vorm A, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Kehoe PG, Rikkert MGMO, van Leeuwen E, Dekkers WJM. Ethical aspects of research into Alzheimer disease. A European Delphi Study focused on genetic and non-genetic research. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(2):140–4.

Black BS, Rabins PV, Sugarman J, Karlawish JH. Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):77–85.

Dubois M-F, Bravo G, Graham J, Wildeman S, Cohen C, Painter K, et al. Comfort with proxy consent to research involving decisionally impaired older adults: do type of proxy and risk–benefit profile matter? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(09):1479–88.

Karlawish J, Kim SYH, Knopman D, van Dyck CH, James BD, Marson D. The views of alzheimer disease patients and their study partners on proxy consent for clinical trial enrollment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):240–7.

Kim SYH. The ethics of informed consent in Alzheimer disease research. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(7):410–4.

Kim SYH, Kim HM, Knopman DS, De Vries R, Damschroder L, Appelbaum PS. Effect of public deliberation on attitudes toward surrogate consent for dementia research.—PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [Cited 2017 Jan 4]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/77/24/2097.short .

Olde Rikkert MG, van der Vorm A, Burns A, Dekkers W, Robert P, Sartorius N, et al. Consensus statement on genetic research in dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(3):262–6.

SYH Kim, J Karlawish, BE Berkman. Ethics of genetic and biomarker test disclosures in neurodegenerative disease prevention trials.—PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [Cited 2017 Jan 4]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/84/14/1488.short .

Arribas-Ayllon M. The ethics of disclosing genetic diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: do we need a new paradigm? Br Med Bull. 2011;100(1):7–21.

Chao S, Roberts JS, Marteau TM, Silliman R, Cupples LA, Green RC. Health behavior changes after genetic risk assessment for Alzheimer disease: the REVEAL study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(1):94–7.

Christensen KD, Roberts JS, Uhlmann WR, Green RC. Changes to perceptions of the pros and cons of genetic susceptibility testing after APOE genotyping for Alzheimer disease risk. Genet Med. 2011;13(5):409–14.

Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Brown T, et al. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):245–54.

Salmon D, Lineweaver T, Bondi M, Galasko D. Knowledge of APOE genotype affects subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2012;8(4):P123–4.

West E, Stuckelberger A, Pautex S, Staaks J, Gysels M. Operationalising ethical challenges in dementia research—a systematic review of current evidence. Age Ageing. 2017;1–10.

Strech D, Mertz M, Knuppel H, Neitzke G, Schmidhuber M. The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care: systematic qualitative review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(6):400–6.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Companion Qual Res. 2004;1:159–76.

Google Scholar

Thorogood A, Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen A, Brodaty H, Dalpé G, Gastmans C, Gauthier S, et al. Consent recommendations for research and international data sharing involving persons with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(10):1334–43.

Jack Cr, Da B, K B, Mc C, B D, Sb H, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 24]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29653606/ .

Gainotti S, Imperatori SF, Spila-Alegiani S, Maggiore L, Galeotti F, Vanacore N, et al. How are the interests of incapacitated research participants protected through legislation? An Italian study on legal agency for dementia patients. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11150.

Knüppel H, Mertz M, Schmidhuber M, Neitzke G, Strech D. Inclusion of ethical issues in dementia guidelines: a thematic text analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001498.

Hanson LC, Gilliam R, Lee TJ. Successful clinical trial research in nursing homes: the improving decision-making study. Clin Trials Lond Engl. 2010;7(6):735–43.

Garand L, Lingler JH, Conner KO, Dew MA. Diagnostic labels, stigma, and participation in research related to dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2(2):112–21.

Heggestad AKT, Nortvedt P, Slettebø Ashild. The importance of moral sensitivity when including persons with dementia in qualitative research. Nurs Ethics. 2012;0969733012455564.

Slaughter S, Cole D, Jennings E, Reimer MA. Consent and assent to participate in research from people with dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(1):27–40.

Sofaer N, Strech D. Reasons why post-trial access to trial drugs should, or need not be ensured to research participants: a systematic review. Public Health Ethics. 2011;4(2):160–84.