- Mission and Vision

- Scientific Advancement Plan

- Science Visioning

- Research Framework

- Minority Health and Health Disparities Definitions

- Organizational Structure

- Staff Directory

- About the Director

- Director’s Messages

- News Mentions

- Presentations

- Selected Publications

- Director's Laboratory

- Congressional Justification

- Congressional Testimony

- Legislative History

- NIH Minority Health and Health Disparities Strategic Plan 2021-2025

- Minority Health and Health Disparities: Definitions and Parameters

- NIH and HHS Commitment

- Foundation for Planning

- Structure of This Plan

- Strategic Plan Categories

- Summary of Categories and Goals

- Scientific Goals, Research Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Research-Sustaining Activities: Goals, Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Outreach, Collaboration, and Dissemination: Goals and Strategies

- Leap Forward Research Challenge

- Future Plans

- Research Interest Areas

- Research Centers

- Research Endowment

- Community Based Participatory Research Program (CBPR)

- SBIR/STTR: Small Business Innovation/Tech Transfer

- Solicited and Investigator-Initiated Research Project Grants

- Scientific Conferences

- Training and Career Development

- Loan Repayment Program (LRP)

- Data Management and Sharing

- Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Population and Community Health Sciences

- Epidemiology and Genetics

- Medical Research Scholars Program (MRSP)

- Coleman Research Innovation Award

- Health Disparities Interest Group

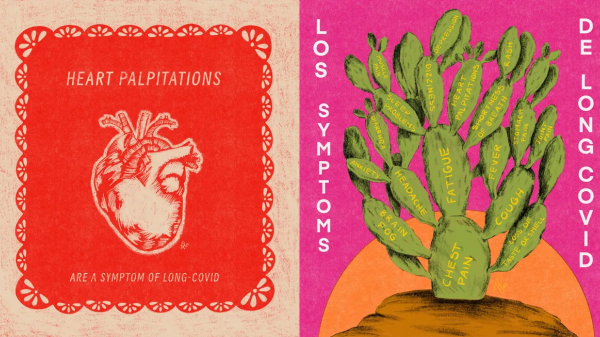

- Art Challenge

- Breathe Better Network

- Healthy Hearts Network

- DEBUT Challenge

- Healthy Mind Initiative

- Mental Health Essay Contest

- Science Day for Students at NIH

- Fuel Up to Play 60 en Español

- Brother, You're on My Mind

- Celebrating National Minority Health Month

- Reaching People in Multiple Languages

- Funding Strategy

- Active Funding Opportunities

- Expired Funding Opportunities

- Technical Assistance Webinars

- Community Health and Population Sciences

- Clinical and Health Services Research

- Integrative Biological and Behavioral Sciences

- Intramural Research Program

- Training and Diverse Workforce Development

- Inside NIMHD

- ScHARe HDPulse PhenX SDOH Toolkit Understanding Health Disparities For Research Applicants For Research Grantees Research and Training Programs Reports and Data Resources Health Information for the Public Science Education

- News and Events

- Improving Health Through Place-Based Interventions

- News Releases

- NIMHD in the News

- Conferences & Events

- Research Spotlights

- E-Newsletter

- Grantee Recognition

Working with Communities to Improve Health

Improving health is not always a matter of prescribing the right medicine. Sometimes the environment needs to change. Many Americans live in neighborhoods that lack safe walking routes, grocery stores, and health facilities.

“Are there places for kids to play? Are there good farmers markets or grocery stores?” asks Irene Dankwa-Mullan, M.D., M.P.H., formerly of NIMHD and now deputy chief health officer of IBM Watson Health. Such features help people in a neighborhood live healthier lives. Along with NIMHD director Eliseo Pérez-Stable, Dr. Dankwa-Mullan wrote an editorial in the April 2016 issue of the American Journal of Public Health , “Addressing Health Disparities Is a Place-Based Issue.”

Efforts to address these problems in particular communities are called “place-based interventions.” Ideally, these interventions come from a collaboration among community members, businesses, and other stakeholders, working together with police, urban planners, and other groups to improve their neighborhood. Community members are involved to make sure the interventions are based on their values.

Examples of place-based interventions include an effort to bring a farmers market to a neighborhood without a grocery store or promoting public safety so that residents feel safe walking on the street. Walking is a simple way to improve health, but there can be many barriers to walking, a fact highlighted in the Surgeon General’s Call to Action on walking .

Place-based interventions have been used successfully in rural areas, disadvantaged urban neighborhoods, and Indian reservations. People who live in such places tend to have particular health problems, such as diabetes and heart disease, and working to change the place-based conditions may help address health disparities.

Communities are complicated, and figuring out the best way to improve the health of all residents in a particular place can be a daunting task. “Part of the issue is that we do not have a best practices model for place-based interventions,” Dr. Dankwa-Mullan says. The editorial in the American Journal of Public Health was part of a new series on best practices for place-based interventions. Through this series, public health professionals will be able to learn how to develop place-based interventions.

One key to success of place-based interventions is involving the community. This is similar to community-based participatory research, a way of doing research in which the community sets priorities, ensuring that communities that are asked to participate in research get answers to the questions that are most important to them.

A research program in Baltimore is looking at bringing healthier food to African Americans who have high blood pressure and mild or moderate chronic kidney disease. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet can lower blood pressure without medication. But it can be difficult for people who live in low-income areas with few supermarkets to get the vegetables and other healthy foods that are part of the diet. In the study led by an NIMHD grantee , participants will learn about the DASH diet and receive $30 per week of potassium-rich foods. Researchers will monitor participants’ blood pressure and kidney health to see whether the intervention helps.

In rural Kentucky , another NIMHD grantee is trying to improve health by teaching children about healthy foods and drinks, in cooperation with community organizations and farmers markets.

Another NIH-funded project in Baltimore is exploring alcohol policies that may reduce neighborhood violence. The researchers are examining how the density of liquor stores affects violence among youth.

These studies are not only delivering interventions; they are testing whether the individual interventions work to improve health. “Programs need to have evaluations or metrics of success,” Dr. Dankwa-Mullan says. “We need more research on the impact.” By funding research on place-based interventions, NIMHD hopes to find out the best ways to improve the health of disadvantaged people and reduce health disparities.

- Dankwa-Mullan, I., & Pérez-Stable, E. (2016). Addressing health disparities is a place-based issue . American Journal of Public Health , 106, 637–639. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303077.

- Johnson, L. A. (1974). The people of East Harlem . New York, NY: Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

- McDermott, W., & Deuschle, K. W. (1970). The people’s health: Anthropology and medicine in a Navajo community . New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Posted May 1, 2017

More Information

Read about what is happening at NIMHD at the News and Events section

NIMHD Fact Sheet

301-402-1366

Connect with Us

Subscribe to email updates

Staying Connected

- Funding Opportunities

- News & Events

- HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

- Privacy/Disclaimer/Accessibility Policy

- Viewers & Players

Community engaged learning brings students, locals together to solve health problems

December 14, 2022 – Over the summer, eight students from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health partnered with organizations and community members from Boston to Nairobi, Kenya to learn about and help address locally identified public health problems. The students—members of the Spring 2022 cohort of Community Engaged Learning Fellows —spoke about their work at a December 6 event at the School.

The students’ projects included working with a Boston health collaborative, a clinic in Uganda, and cobalt miners in the Democratic Republic of Congo, among others. A common thread across the students’ presentations was their effort to draw on community knowledge to develop creative solutions together.

Jen Cruz , PhD ’26, partnered with the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative (ABHC), a public health nonprofit that convenes organizations, health advocates, elected officials, and residents to improve the systems that impact health and wellbeing in Boston’s Allston and Brighton neighborhoods.

Before she worked with ABHC on her fellowship project, Cruz—an Allston resident herself—volunteered for the Collaborative’s vaccine clinic. Since then, she has supported ABHC by serving on its mental wellness and transportation working committees, and plans to join the advisory board in 2023.

In her committee work, Cruz became aware that some of her fellow volunteers were reticent about advocating for their own priorities regarding the Collaborative’s decision-making about programs and policies for marginalized and under-resourced community members. Instead, they sometimes would ask Cruz to speak on their behalf in the hope that her public health expertise would strengthen their input.

“You shouldn’t have to have an MPH or degree in public health to contribute to the conversation, understand what the news is telling you, and make informed decisions about your health,” Cruz said. So, for her fellowship project, Cruz helped develop an educational program aimed at engaging community members as leaders in ABHC’s work.

Erin McGuinness , DrPH ’24, and Yacine Fall , SM ’23—the inaugural recipients of the Global Mental Health Fellowship , which offers students opportunities to partner with organizations outside the U.S. to address mental health issues in their communities—spoke about their work collaborating with the John Cleaver Kelly Clinic in Kabale, Uganda. They worked with the clinic on evaluating its community mental health outreach, including understanding the perspective of community health workers, patients, and families.

Alina Bhojani , SM ’23, and Alya Al Sager , SM ’23, discussed their experience working with Kidogo, a Kenya-based social enterprise building an expanding network of childcare centers in Nairobi’s urban slums. Kidogo supports female entrepreneurs—who they call “Mamapreneurs”—in starting childcare businesses in their own communities. Al Sager and Bhojani worked with Kidogo to tailor its early childhood development program so that Mamapreneurs would be more likely to use it in their centers.

Learning from locals

Under the Community Engaged Learning Fellows program, student cohorts are chosen each spring and fall to help respond to community-identified concerns, striving to balance the service they provide with their learning experience. Jocelyn Chu , director of the program, spoke about the benefits students gain from their field education and practice experiences.

“Public health education has the unique opportunity to incorporate field-based learning and training to sharpen skills in collaborative approaches and community engagement,” Chu said. “With an invitation to take on the posture of a ‘learner in the field,’ we have witnessed transformative learning experiences that have gone on to impact the career trajectories of our fellows.”

Other Spring 2022 Community Engaged Learning Fellows who presented at the December event included:

- Benita Kayembe , SM ’23, investigated the effects of artisanal cobalt mining on miners’ health in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—where up to 60% of the global supply of cobalt is sourced—with a goal of informing policymaking and building programs to improve miners’ quality of life.

- Christian Groth-Hoover , MPH ’23, worked with Massachusetts gun owners on the best means of communicating the dangers of lead exposure from firearms.

- Kaitlin Schroeder , MPH ’23, worked with the Boston Public Health Commission to develop culturally appropriate, community-facing messaging on colorectal cancer detection, which led to more residents getting tested.

– Catherine Seraphin

Photo: Catherine Seraphin

The Role and Potential of Communities in Population Health Improvement: Workshop Summary (2015)

Chapter: 5 how institutions work with communities.

5 How Institutions Work with Communities

The third panel of the workshop considered the role of institutions (academic, government, and private) in working with communities to build capacity and support change. An example of how a university can partner with community-based groups was provided by Jomella Watson-Thompson, an assistant professor in the Department of Applied Behavioral Sciences and the associate director for Community Participation and Research and the University of Kansas (KU) Work Group for Community Health and Development. Renee Canady, the chief executive officer of the Michigan Public Health Institute, discussed achieving collective impact through collaboration from her perspective as a former county health officer. Individual participants then discussed the importance of engaging the private sector as partners, the importance of collecting data with utility in mind, and, again, how to scale community organizing efforts. The discussion was moderated by Melissa Simon, an associate professor in obstetrics and gynecology, general and preventive medicine, and medical social sciences at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

MULTISECTOR PARTNERSHIPS

KU partners with various community-based groups, from grassroots neighborhood-based organizations to state and local departments, to build community capacity to support change and improvement, said Watson-Thompson from KU. Referring to a famous quote from Margaret

Mead—“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed it is the only thing that ever has.” Watson-Thompson said that such small groups of individuals can be found in neighborhoods, in agencies and universities, and in organizations, including faith communities.

The Power of Partnerships

Watson-Thompson described to the workshop her first personal experience with capacity building, which took place in 1997. A father of four young children in the Ivanhoe neighborhood of Kansas City had become frustrated with the ills in his neighborhood, which included crime, drugs, and vacant housing, and he and his wife began to organize prayer vigils and other activities in the community. The couple then began to work with other groups that had expertise in community organization and mobilizing. The KU Work Group for Community Health and Development 1 provided technical support and training. Seventeen years later, the Ivanhoe Neighborhood Council 2 is still committed to neighborhood improvement. Echoing the comments of other presenters, Watson-Thompson said that a key element in the success of that effort was the provision of adult development (community education, training, and capacity-building activities) to help those in the community come together, solve their own problems, and sustain progress after the technical advisers left.

Watson-Thompson described how more than 100 block leaders came together to develop block-level plans to support change and improvement. These leaders also engaged in multi-sector partnership with academia (the KU Work Group), businesses, government agencies, schools, and residents. The KU Work Group facilitated 117 community changes, which led to improvements in various community outcomes, including housing and crime. Over a 4-year period, there was a 54 percent increase in housing loan applications, a 17 percent decrease in violent crime, and a 20 percent decrease in non-violent crime. After addressing the most pressing needs, the Ivanhoe Neighborhood Council moved on to other community needs, such as parks and farmers markets. This is an example of a general principle in community organizing, Watson-Thompson said: If one person in a community steps up and leads, others will join.

In another multisector partnership, the KU Work Group worked with the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services and with community coalitions in 14 Kansas counties to address underage drinking using the Kansas Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant. Overall,

____________

1 For more information see https://communityhealth.ku.edu (accessed August 15, 2014).

2 See http://www.incthrives.org (accessed August 15, 2014).

Watson-Thompson said, there were 802 program policy changes implemented through engaging 12 sectors of the community, which resulted in a 9.6 percent decrease in self-reported 30-day alcohol use by youth in the 14 counties. This initiative has become a model in Kansas for how to support prevention work, Watson-Thompson said. Another example is the Latino Health for All Coalition, which works to address disparities in cardiovascular disease and diabetes in Kansas City by providing access to healthier foods, safe activities, and health care. The collaborative partnership supported 41 program, policy, and practice changes over the initial 3-year program period. 3

Watson-Thompson said that each of these successful efforts adhered to three key principles for supporting population-level improvement:

- Focus on the outcome. Work with community partners to identify the behaviors that need to be changed at the community and population levels.

- Change the environment. Transform the community conditions to promote health and well-being.

- Support the change process. Take action to assess, plan, act, intervene, evaluate, and sustain.

A Collaborative Action Framework for Population-Level Improvements

To guide the process of working with community partners, the KU Work Group adapted the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Framework for Collaborative Public Health Action in Communities (IOM, 2003, p. 178) (see Figure 5-1 ). All activity is implemented based upon the direction of the community partners, Watson-Thompson said. The key responsibility of the academic partner is to support the ability of other partners to implement these processes (see Table 5-1 ). Watson-Thompson stressed that this is not prescribing the process to the other partners, but rather providing the support so that they can implement and maintain the processes (Fawcett et al., 2010).

Change and improvement in communities is the result of comprehensive interventions. While single-dose (i.e., one-program) interventions are important, Watson-Thompson said that addressing complex and interrelated problems requires an influx of program, policy, and practice changes. When these community- and system-level changes are of suf-

3 A review of collaborative partnerships may be found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10884958 (accessed July 25, 2014).

FIGURE 5-1 Framework for collaborative action for improving health and development. SOURCE: Watson-Thompson presentation, April 10, 2014, adapted from IOM, 2003, Figure 4-1, p. 178.

ficient intensity and penetration, they can achieve population-level outcomes (Fawcett et al., 2003).

Watson-Thompson highlighted several core principles, assumptions, and values that guide the KU Work Group on community and health development. Improvements are directed toward the population and require change both in behaviors of groups of people and in the conditions of the environment. Issues should be determined by those most affected, she said, and attention should be on the broader social determinants of health. Because these are influenced by multiple interrelated factors, single interventions are unlikely to be sufficient. Change requires

TABLE 5-1 Best Processes for Capacity and Change Identified by Watson-Thompson and Others

SOURCE: Watson-Thompson presentation, April 10, 2014, adapted from Fawcett et al., 2010.

engaging diverse groups across sectors as well as collaboration among multiple partners. Finally, she concluded, partners are catalysts for change, building the capacity to address what matters to people in the community.

Challenges and Opportunities for Academic Institutions

In closing, Watson-Thompson said that the community members are the experts and the researchers are co-learners in the process. It is important to build trust and rapport with community partners and to assure early wins to build shared success and empower the community. This requires an infusion of resources and a commitment over time and across people (i.e., across changes in leadership). It is important to stay at the table and to be part of the process and, as noted by others, also to make sure to contribute to the community. Academia is a base for supporting change and improving the community, and it is the collective responsibility of academics working with communities to have collective impact, she concluded. The key aim, Watson-Thompson said, is to have “community-engaged scholarship” where collaborative research, teaching, and public service is integrated.

COLLABORATION AND COLLECTIVE IMPACT

Canady shared her perspectives on collaboration and collective impact based on her prior experiences as health officer for the Ingham County, Michigan Health Department. Collective impact is “long-term

commitments by a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific problem,” she said. “Their actions are supported by a shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, and ongoing communication, and are staffed by an independent backbone organization.”

Collaboration is not the same as community engagement, which is not the same as community organizing, which is not the same as collective impact, she said. Citing Edmonson (2012), she explained that collaboration is about convening around programs and initiatives while declaring neutrality, whereas collective impact is more about working together to move outcomes. While collaboration uses data to prove things, collective impact tries to improve things. Collaboration is usually something in addition to what people already do, while collective impact entails integrating practices that get results into everyday work. Finally, collaboration is often about advocating for ideas, while collective impact advocates for what works. As an example, Canady said that when public health practitioners were focused on childhood obesity, the community responded that if children do not live to be 10, it does not matter if they are fat. In other words, violence and safety were the primary concerns of the community, and public health officials needed to shift their focus to address that. As defined by the Leadership Development National Excellence Collaborative, 4 collaborative leadership in public health means that all the people affected by the decision are a part of the process, and the more that power is shared, the more power all of us working together have to use, Canady said.

Authentic Collaboration Between Institutions and Communities

Canady described three spheres of influence in a model of authentic collaboration between institutions and communities: leadership, the community, and the workforce. There is endorsement by leadership; engagement of, or advocacy by, community members who want to create change; and a workforce that is empowered to respond and to challenge the status quo. Collectively, the impact of the three together is greater than that of any one alone. In many cases, Canady noted, one person represents more than one sphere.

As an example, Canady said that in 1998 the Ingham County Health Department received a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Community Voices: Healthcare for the Underserved initiative to increase access to health care through community engagement. As part of its funded work, Ingham County began facilitated dialogues to discuss how

4 See http://www.collaborativeleadership.org (accessed July 24, 2014).

to get community groups, organizations, and neighborhoods to see health department resources as their assets and how to get the health department to view the community’s assets as its greatest resource. Canady characterized these dialogues as emerging out of the need to recognize the “web of mutuality” between health departments and communities. 5 An outgrowth of these dialogues was the establishment of institutions and organizations that began to work with the health department on these issues, including the African-American Health Institute, the Lansing Latino Health Alliance, and others. These exist, Canady said, because the community drove the health department to use its power to establish those entities. Relationships were also established with leadership in the Mayor’s Initiative on Race and Diversity.

Another example of establishing relationships to mobilize community assets for change in Ingham County is the Power of We Consortium (see Figure 5-2 ). Canady described how the directors of different human services agencies met regularly to ensure there was no redundancy in their services. Canady said that likely because of the mutual dialogue and learning they received individually and institutionally, they realized that others should be at the table joining them. Over time, what was called the human services collaborative, was opened up to the community and the Power of We Consortium was formed. The consortium, Canady said, is a network of networks, comprised of 12 issue-based coalitions as well as other community partners and stakeholders which come together once per month to work on issues of common interest and to hold each other accountable.

Canady also described two current activities in Ingham County that are part of a statewide push for public health professionals to partner with community organizers and to view the community as partners rather than as clients. The Building Bridges Initiative is focused on mobilizing community partnerships to identify and solve health problems and on informing, educating, and empowering people about health issues. The Power to Thrive movement is building a shared culture for change and action, bringing together local health departments, the state department of health, and community organizing entities to consider public health issues in a local context. Canady explained that the movement’s goal is to establish a model of synergy that allows for candid and authentic conversations and discussions that move toward action.

5 Canady mentioned Martin Luther King, Jr., and was likely referring to King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” where he discussed the “network of mutuality” in which whatever threat is faced directly by one, indirectly affects all. Available at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/resources/article/annotated_letter_from_birmingham (accessed July 16, 2014).

FIGURE 5-2 The Power of We Consortium structure. NOTE: This figure has been updated since Canady presented it at the workshop, courtesy of the Power of We Consortium. SOURCE: Provided by Power of We Consortium, 2014.

Facilitated Dialogue as a Vehicle for Change

Ingham County used facilitated dialogue as a vehicle for change. In implementing this methodology, it was important to establish what a dialogue is and to distinguish it from debate, training, or conversation. In a debate, Canady said, competing factions use persuasion to convince others of the “best” solution. In contrast, dialogue focuses on a common purpose, emphasizing listening, in order to identify multiple, complementary solutions. Training is a unidirectional flow of information, embracing what is known and teaching new solutions. Dialogue is a mutual exchange of information, embracing what is not known and discovering new solutions together. A conversation is a casual, undirected exploration where differences are marginalized. Dialogue, on the other hand, is a vigorous and directed exploration that welcomes differences (without debating them). The philosophy of the facilitated dialogue, Canady said, is that institutions should “get out of the way” and allow the solutions to emerge according to each community’s vision for being healthy and whole.

Melissa Simon, the panel moderator, summarized some of the key points from the panel presentations, and she noted that some of what was discussed circled back to what keynote speaker Manuel Pastor articulated earlier in the day about sharing power to harness more power (see Chapter 2 ). Simon noted that both panelists demonstrated the power of “we,” and how sharing power among partners—be they organizers, academics, social and health service providers, policy makers, youth, fathers or mothers—speaks to the power of communities. This idea of network building from one person to many, helps propel this work and to scale it. Building powerful communities and community partners is an authentic part of creating change by establishing relationships that involve long-term commitment, mutuality, and shared visions and dreams that need to be reinforced and maintained over time.

Simon continued that it is apparent from the presentations that building a new narrative through facilitated dialogue involving a diversity of community partners can be a vehicle for change. This involves breaking down silos and building relationships with people across sectors. It also involves having authentic dialogues with people and moving beyond the surface to listen and learn from another person’s story, she added. Simon also noted that concealed stories (as discussed by Karen Marshall in Chapter 3 ) needed to be heard more widely so they could be part of the dialogue shaping a shared vision for change. Simon added that achieving the kind of change discussed by the presenters may best be accomplished by rethinking how ecosystem partners can use their relationships strategically to amplify and champion this work through understanding that both the community and academic institutions have resources and assets to help each other.

Engaging the Private Sector

A participant stressed the importance of engaging private sector community partners in a meaningful way. Canady concurred and said that inviting small business owners and representatives to the table is important for discussions about fostering personal responsibility (e.g., what can be done structurally in stores to make sure that the healthy choice is the easy choice, rather than one that requires additional effort or resources). She mentioned the California Pay for Success/Social Impact Bond Initiative as an example of meaningful engagement of private partners. 6

6 Private investors fund preventative or interventional social services, and, if the program is a success, the government reimburses the investors with a return on their investment. See http://nonprofitfinancefund.org/pay-for-success (accessed July 24, 2014).

Collecting Data with Utility in Mind

Many participants discussed the challenges of balancing academia’s need for robust data with community members’ weariness with data collection on issues that they think may be obvious (e.g., everyone in the community already knows they have limited access to fresh food). Phyllis Meadows remarked that community members often feel they can tell the researchers the answers to the questions they are researching, but the researchers end up simply describing the community’s problems over and over, in different ways, or gathering data that does not seem useful to the community and does not help them advance.

Watson-Thompson agreed that there is a tension between the data that academic partners need to collect and the interpretation of that work by communities. She reiterated the value of engaging the community at the beginning of the process in identifying the questions that need to be examined, the different ways in which to examine them, and how best to share and use the results. The researcher’s perspective on the types of data that are appropriate may differ from the community’s perspective on what is meaningful or helpful to them. Data are only good if used, so sharing the data in a way that is understandable to the community is also essential. Traditional academic formats may not be an effective approach. The quantitative piece is more meaningful when matched with the qualitative (i.e., the stories). Watson-Thompson suggested that validity testing is needed to determine if what is being presented has meaning and utility for those it is intended to serve. She also noted the need to be bi-directional with learning and information-sharing processes. It is important to engage the community to educate academia about ways in which information can be presented and disseminated that are meaningful to them and to establish a culture of data-informed decision making that matters for both parties or entities involved. Canady added that the publish-or-perish mentality of academia also affects how researchers work with communities (see Chapter 6 for additional discussion on this topic). Simon reiterated the need to build a pipeline of research scientists, academics, and leaders coming from (and hopefully returning to) these communities.

As in other sessions, many participants in this session asked questions about how to take community aspirations and efforts to promote health to scale. Canady responded that although everyone is eager for rapid change, it took time to make the progress seen today, and it will take time to understand and achieve long-term change. The process, when done correctly, is leading toward something, she said. Citing the united

efforts to respond to H1N1 pandemic influenza as an example, she said that agencies, institutions, and organizations have to come together, recognizing that each has its own agenda or self-interest, but understanding that there will be greater benefit from collective effort. As a community, we need to hold ourselves accountable to demonstrate what is different today compared to 6 months ago, 1 year ago, or 3 years ago, Canady said.

Organizing for Better Health Care

A question was raised about the potential role of community organizing in addressing the waste in health care in order to free up resources for population health and health equity. A participant suggested that patients and people in the communities need to push for quality care. Equity comes from quality across all metrics. Another participant said that organizing people around the cost efficiency of hospitals is not particularly interesting for most people, but there is a lot of public anger concerning costs that can be tapped.

This page intentionally left blank.

The Role and Potential of Communities in Population Health Improvement is the summary of a workshop held by the Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Population Health Improvement in April 2014 that featured invited speakers from community groups that have taken steps to improve the health of their communities. Speakers from communities across the United States discussed the potential roles of communities for improving population health. The workshop focused on youth organizing, community organizing or other types of community participation, and partnerships between community and institutional actors. This report explores the roles and potential of the community as leaders, partners, and facilitators in transforming the social and environmental conditions that shape health and well-being at the local level.

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- Forgot Password?

- Create Account

- User ID: -->

- Password: -->

Our website has detected that you are using an outdated internet browser. Using an outdated browser can limit your ability to use all of the features on our website, including the ability to make purchases and register for meetings. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Directories

- Community Benefit

- Disaster Resources

- Diversity & Disparities

- Environment

- Global Health

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Ministry Formation

- Ministry Identity Assessment

- Palliative Care

- Pastoral Care

- Sponsorship

- We Are Called

- Calendar of Events

- Assembly 2024

- Safety Protocols

- Prayers During the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Meditations

- For Patients & Families

- Observances

- For Those Who Work in Catholic Health Care

- For Meetings

- Social Justice

- Calendar of Prayers

- Prayer Cards

- Health Progress Prayer Services

- World Day of the Sick Blessing

- The Angel Gabriel En Route to Mary

- The Annunciation and St. Ann

- The Visitation and Zechariah

- The Magi Set Up Camp

- The Nativity and The Midwives

- 2020 Advent Reflections

- Lent Reflections Archive

- Video & Audio Reflections

- Inspired by the Saints

- The Synod on Synodality

- Bibliography of Prayers

- Hear Us, Heal Us

- 2018 Month of Prayer

- 2017 Month of Prayer

- Links to Other Prayer Resources

- Week of Thanks

- Current Issue

- Prayer Service Archives

- DEI Discussion Guide

- Advertising Rates & Specifications

- Subscription Rates

- Author's Guide

- Submit an Article

- Health Progress 100

- HCEUSA Subject Index

- Periodical Review

- 2023 Christmas Advertising

- Submit story ideas to the editor

- Public Health's Role: Collaborating for Healthy Communities

BY: ROBERT M. PESTRONK, M.P.H., JULIA JOH ELLIGERS, M.P.H. and BARBARA LAYMON, M.P.H.

The Commonwealth Center for Government Studies reports that the moment has come to take a fresh look at traditional practices and relationships and to develop new approaches that will serve our communities better and more efficiently. 1 The center also recommends that hospital governance take oversight for both system-wide community benefit policies and programs and for the hospital's role and priorities in the realm of population health. Although many different solutions are now being proposed, most informed observers are unified on one point: The value and the quality of services should correspond to the size of the investment in the clinical care and public health sectors. 2, 3

Local health departments, too, are being asked to re-examine and reprioritize their approaches to improving the public's health 4 through proof of capacity, 5 continuous improvement of the activities they perform 6 and oversight for the outcomes achieved or desired by the public health and health care sector. 7 The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), representing the 2,800 local health departments across the country, sees this time as a true opportunity to improve the public's health.

As collaborative relationships between hospitals and local health departments become the new normal, opportunities abound. The new "community benefit" definition and requirements in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) 8 require hospitals to conduct a community health assessment and produce a community improvement plan. Local health departments are required to produce an assessment and improvement plans. Why not plan and conduct these in a collaborative fashion, making use of the assets, capabilities and capacities which each can offer?

Assessment is a core function of public health. Many local health departments have traditionally conducted community health assessments 9 — approximately 60 percent in the last five years. 10 Many hospitals also have conducted or participated in community health needs assessments related to community benefit programs. Collaborative work will allow local health departments and hospitals around the country to build upon their existing expertise, relationships and experiences to conduct various improvement initiatives partnering together around specific goals.

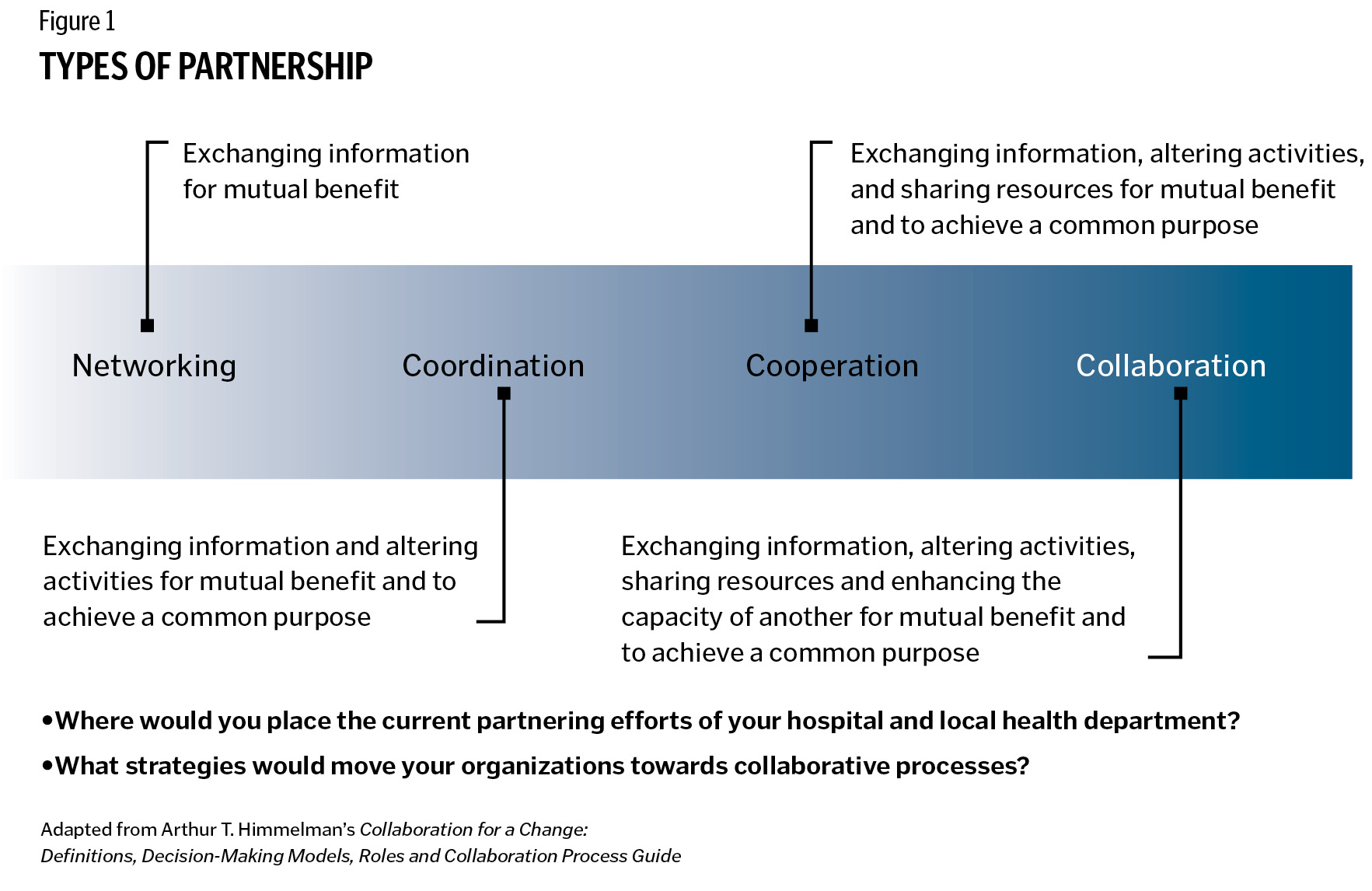

These efforts to partner around community health assessment and improvement planning span four types of strategies: networking, coordinating, cooperating and collaborating. With such collaboration, community health assessment and improvement activities can be precursors to real gains in population health and an integral part of continuous improvement processes towards that goal.

KEYS TO SUCCESSFUL COLLABORATION Over the past year, NACCHO conducted three focus groups with leaders of health departments and nonprofit hospitals across the country to identify what makes community health assessment and improvement collaborations successful between local health departments and hospitals. Common strategies undergirded successful partnerships:

Formalized mechanisms. Communities where local health departments and hospitals work well together have constructed a formalized forum for dialogue. A memorandum of understanding helps clarify the roles and responsibilities of each entity. Further, a written memorandum of understanding helps ensure that collaborative efforts continue even if leadership at either organization changes. In communities where the local health department and hospital do not have a history of working together, a third party can help. In one Florida community, for example, the local health department and hospital used their health planning council to build and strengthen their relationship.

Vision. Successful collaboration is contingent on a shared vision or goal. One focus group participant said, "There's certainly a difference between what is the focus of public health versus individual care and private health care. But in focusing on some of the common goal areas ... that made a big difference."

Another participant pointed out it is important not only to think about what the product and process will look like, but ultimately to determine "what is the end game around the assessment?"

Communication. Frank, open and candid conversations between leaders and staff of local health departments and hospitals enrich relationships between collaboration partners. One local health department representative noted that department staff members learned about the financial and political realities that confront their nonprofit hospital, and their hospital partners learned about the political and financial challenges of governmental public health practice. Shared learning helped develop mutual respect. Together they were more effective in engaging other community organizations and partners.

Neutral convener. When there is more than one hospital in a community, a neutral convener can be helpful to the process of working together. Many local health departments have staff with facilitation skills that can be used to structure and coordinate collaborative assessment and improvement activities involving usually competitive area hospitals. One hospital executive said, "There are times when you have to put down the competition and raise a flag of collaboration, and that's what we've been able to do. I credit that to the health department for being able to put us all around the table and get some work done."

Champions and Leaders. Effective collaboration requires each organization to have champions who will move the effort forward. The champions can arise from formal leaders or other staff members; each background has advantages. A formal organizational leader can motivate and assign work to staff members, while a staff member's interest, energy and enthusiasm can infect leaders and other staff.

A successful collaboration needs support from local health officials and from hospital executives. Focus group participants noted that with leadership on board, their staffs, the community and partner organizations then seem to acknowledge the importance of assessment and improvement work. Several focus group participants commented that hospital executives, in particular, bring a level of prestige to assessment and improvement initiatives.

Attitude. Building trust and positive relationships takes time. A representative of a hospital nonprofit commented, "The hospitals that see the community health improvement process as an opportunity to improve community health, rather than an obligation, tend to be more successful." Challenges arise in any relationship. Focus groups revealed some of them. Competitive hospitals usually can work together on community health assessment processes, even if it's difficult for them to work together on other activities. One focus group member said that in her jurisdiction, competing hospitals pooled their resources to make sure the needs and requirements of the community health needs assessment process were met in a collaborative way. The group also included other health care providers (for example, a rehabilitation center) who helped bring in more data and ideas.

One participant observed that when hospitals are highly competitive, it's sometimes difficult to get them both on the same page, but once you get one hospital on board, other hospitals begin to show interest.

The timetable of the new Internal Revenue Service requirement for hospitals does not necessarily coincide with the timing of health department reporting and planning requirements; however, hospitals and health departments can work together to design a process and data management system that produces results they each can use.

Health department jurisdictions may encompass several hospitals. Hospital market areas may span many local health department jurisdictions. Flexible designs and processes among multiple hospitals and local health departments can overcome jurisdictional boundary issues.

TOWARDS HEALTHIER COMMUNITIES There are many ways that local health departments and hospitals can pool their resources of time, talents, data, knowledge, partner base and funding to support collaborative efforts to achieve healthier communities. Local health departments and hospitals bring complementary strengths in many areas, including:

Data: While local health departments have vital statistics and county mortality and morbidity data on their jurisdictional population, hospitals have data on their patient population. Some local health departments have data specific to census tracks or neighborhoods, data on social determinants of health and data on behavioral risk factors. Further, many health departments have data on the communities' perceptions of quality of life. Some local health departments have conducted forces of change assessments that identify externalities that can have an impact on health, while others have conducted public health system assessments that measure how well local organizations work together to provide essential services. Many local health departments also have collected qualitative data on assets that can be leveraged to solve health problems. When viewed together, data from local health departments and from hospitals provides a more complete picture of a community's health challenges. That picture creates a shared understanding that can inform potential solutions.

Skills and Processes: Many local health departments have skills specific to community health assessment and improvement. Local health departments already have well-established processes for completing community health assessment and improvement processes. In focus groups, several local health department representatives commented that their hospital partners were happy to hear the local health department had a structured process like Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) 11 that would help them meet their assessment requirements.

Local health departments also may have assessment-related experience in data collection, data analysis, community outreach, facilitation, health education and wellness programs. One advantage of the local health department as facilitator is its ability to find and maintain multiple contacts — many champions — within partner organizations in order to manage details which come up in collaborative efforts. Similarly, hospitals may have processes in place to conduct community health improvement work such as patient education, wellness programs, outreach and other activities that can be natural adjuncts to local health department activity.

Partners: Many local health departments have access to a variety of nontraditional and community partners, working directly with community residents and grassroots organizations. Some have staff members with skills in qualitative methods, such as key-informant interviews and focus groups, whose work provides rich context and explanatory power to quantitative data. Hospitals have partners and board members who bring a certain stature to the work of engaging a community, adding legitimacy and the chance of acceptance for initiatives that may bring far-reaching health changes. A health department executive added that it's important to have the right people in the room who are aware of all the resources available from their organizations.

Health Equity: In the community health dialogue, local health departments bring a public health view regarding the central importance of assuring the conditions where people can be healthy. Hospitals bring experience in the care and treatment of members of marginalized populations, and they bring a needed perspective to the health equity conversation.

Through collaborative community health assessment, local health departments and hospitals have been able to implement well-informed organizational strategic plans and collaborative, overarching community-health improvement plans. Collaborative community health assessments have allowed organizations to identify the needs of specific subpopulations and develop solutions to their unique needs. What's more, other organizations then can align and integrate portions of their strategic plans with a community health improvement plan. Further, collaboration among local health departments, hospitals and other entities have resulted in comprehensive assessments that inform grant proposals, public policy and ways for organizations to work more efficiently and effectively together.

Partnerships between hospitals and local health departments have proven productive in many communities. Better organized systems of care can assure that both treatment and prevention are artful and evidence-based. Designed attention to the unique goals, roles and needs of hospitals and local health departments will benefit from the strengths and assets each partner offers. Communication and dialogue among hospitals, health departments and other local partners can lead to concurrence and a prioritization based on the community's risks to health and remedies to prevent disease. Other benefits include a shared understanding of problems, transparency about efforts to improve health and treat illness and better public support for each partner and the partnership.

Collaborative community health assessment and community health improvement processes should be standard practice everywhere. Effective collaboration will require intent and patience as very different cultures come to know each other better. Leadership in both organizations must encourage the awkward steps that will no doubt precede the more elegant and practiced choreography of effective collaborations.

What will be discovered on the journey is a better command of the role that each entity can play in a re-forming medical and public health system and, more important, better success with their shared mission of population health.

ROBERT M. PESTRONK is executive director for the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) in Washington, D.C.

JULIA JOH ELLIGERS is NACCHO's director, assessment, planning and workforce development, Washington, D.C.

BARBARA LAYMON is lead program analyst for assessment and planning within NACCHO's public health infrastructure and systems team, Washington, D.C.

- Lawrence Prybil et al., Governance in Large Nonprofit Health Systems: Current Profile and Emerging Patterns (Lexington, Ky.: Commonwealth Center for Governance Studies, 2012). www.hallrender.com/health_care_law/library/articles/1220/Governance_booklet.pdf .

- Joseph R. Antos, Mark V. Pauly and Gail Wilensky, "Bending the Cost Curve through Market-Based Incentives," New England Journal of Medicine 367 (Sept. 6, 2012), www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb1207996 (accessed 8/3/12).

- Ezekiel Emanuel et al., "A Systemic Approach to Containing Health Care Spending," New England Journal of Medicine 367 (Sept. 6, 2012), www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb1205901 (accessed 8/3/12).

- Institute of Medicine, For the Public's Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability (Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 2010). See more at www.iom.edu/Reports/2010/For-the-Publics-Health-The-Role-of-Measurement-in-Action-and-Accountability.aspx .

- See Public Health Accreditation Board, www.phaboard.org/accreditation-overview/what-is-accreditation/ .

- National Association of County and City Health Officials, Operational Definition of Public Health (Washington, D.C.: NACCHO, 2005), www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/accreditation/upload/OperationalDefinitionBrochure-2.pdf .

- IOM, For the Public's Health .

- The Affordable Care Act requires nonprofit hospitals to conduct community health needs assessments. The public health field does not limit community health assessments to identifying needs and therefore are using the term community health assessment, excluding the explicit reference to needs. Community health assessments that are limited to uncovering needs do not comprehensively identify community issues and solutions to addressing problems. Often public health community health assessments include information about community assets and other information about forces, quality of life and how different providers work together to deliver services, which provides a comprehensive illustration on why needs and public health problems exist in a community.

- The National Association of County and City Health Officials, Issue Brief: Collaborating through Community Health Assessment to Improve the Public's Health . December 2011. Downloaded at www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/mapp/loader.cfm?csModule=security/getfile&pageID=228716 .

- National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2010 National Profile of Local Health Departments (Washington, D.C.: NACCHO, 2011), www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/2010report/upload/2010_Profile_main_report-web.pdf .

- For more information about the MAPP (Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships) process, visit www.naccho.org/mapp .

Copyright © 2013 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.

Copyright © 2013 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.

Back to Top

Also in this Issue

- U.S. Health Care Is Moving Upstream

- Public Health Workers Needed: Educational Programs Grow as Shortage Looms

- Catholic Health Systems Steer the New Course

- A Model Strategy: Targeting Infant Mortality Can Produce Results

1625 Eye Street NW Suite 550 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 296-3993

ST. LOUIS OFFICE

4455 Woodson Road St. Louis, MO 63134 (314) 427-2500

- Social Media

- Focus Areas

- Publications

- Career Center

We Will Empower Bold Change to Elevate Human Flourishing SM

© The Catholic Health Association of the United States. All Rights Reserved.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Finding middle way out of Gaza war

Navigating Harvard with a non-apparent disability

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Community engaged learning brings students, locals together to solve health problems.

Photo by Catherine Seraphin

Over the summer, eight students from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health partnered with organizations and community members from Boston to Nairobi, Kenya, to learn about and help address locally identified public health problems. The students — members of the spring 2022 cohort of Community Engaged Learning Fellows — spoke about their work at a Dec. 6 event at the School.

The students’ projects included working with a Boston health collaborative, a clinic in Uganda, and cobalt miners in the Democratic Republic of Congo, among others. A common thread across the students’ presentations was their effort to draw on community knowledge to develop creative solutions together.

Jen Cruz , Ph.D. ’26, partnered with the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative (ABHC), a public health nonprofit that convenes organizations, health advocates, elected officials, and residents to improve the systems that impact health and well-being in Boston’s Allston and Brighton neighborhoods.

Before she worked with ABHC on her fellowship project, Cruz — an Allston resident herself — volunteered for the Collaborative’s vaccine clinic. Since then, she has supported ABHC by serving on its mental wellness and transportation working committees, and plans to join the advisory board in 2023.

In her committee work, Cruz became aware that some of her fellow volunteers were reticent about advocating for their own priorities regarding the Collaborative’s decision-making about programs and policies for marginalized and under-resourced community members. Instead, they sometimes would ask Cruz to speak on their behalf in the hope that her public health expertise would strengthen their input.

“You shouldn’t have to have an M.P.H. or degree in public health to contribute to the conversation, understand what the news is telling you, and make informed decisions about your health,” Cruz said. So, for her fellowship project, Cruz helped develop an educational program aimed at engaging community members as leaders in ABHC’s work.

Erin McGuinness , Dr.P.H. ’24, and Yacine Fall , S.M. ’23 — the inaugural recipients of the Global Mental Health Fellowship , which offers students opportunities to partner with organizations outside the U.S. to address mental health issues in their communities — spoke about their work collaborating with the John Cleaver Kelly Clinic in Kabale, Uganda. They worked with the clinic on evaluating its community mental health outreach, including understanding the perspective of community health workers, patients, and families.

Alina Bhojani , S.M. ’23, and Alya Al Sager , S.M .’23, discussed their experience working with Kidogo, a Kenya-based social enterprise building an expanding network of childcare centers in Nairobi’s urban slums. Kidogo supports female entrepreneurs — who they call “Mamapreneurs” — in starting childcare businesses in their own communities. Al Sager and Bhojani worked with Kidogo to tailor its early childhood development program so that Mamapreneurs would be more likely to use it in their centers.

Learning from locals

Under the Community Engaged Learning Fellows program, student cohorts are chosen each spring and fall to help respond to community-identified concerns, striving to balance the service they provide with their learning experience. Jocelyn Chu , director of the program, spoke about the benefits students gain from their field education and practice experiences.

Share this article

You might like.

Educators, activists explore peacebuilding based on shared desires for ‘freedom and equality and independence’ at Weatherhead panel

4 students with conditions ranging from diabetes to narcolepsy describe daily challenges that may not be obvious to their classmates and professors

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

- Community Engagement is Vital to…

Community Engagement is Vital to Solving Local Health Problems

Date posted:.

Editor's note: This post is part of our series in recognition of PolicyLab's 10th anniversary and our ongoing efforts to chart new frontiers in children's health research and policy. Read the first post here , and check back for more content throughout the year!

As one of PolicyLab’s founding members, I have had the privilege of conducting research in the city of Philadelphia for over 17 years. Philadelphia is recognized as one of the poorest of the 11 largest cities in the U.S. As a consequence, Philadelphia’s children are in relatively poor overall health compared to children in other large cities: ranked highest in obesity, smoke exposure, infant and child mortality, low birth weight births and violent crime, and lowest in on-time high school graduation. Yet these statistics belie a vibrant and diverse community, committed to improving the lives of young children. I know this to be true, since I’ve worked with many community organizations and their leadership on projects to improve the lives of Philadelphia youth.

As a result, I have come to value community-engaged (CE) research in my approach to addressing important child health problems. But what is CE research? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has defined community engagement as “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people.” Therefore, CE research is a collaborative process that involves academic researchers and community members working together to solve vexing health problems that neither is adequately positioned on their own to solve.

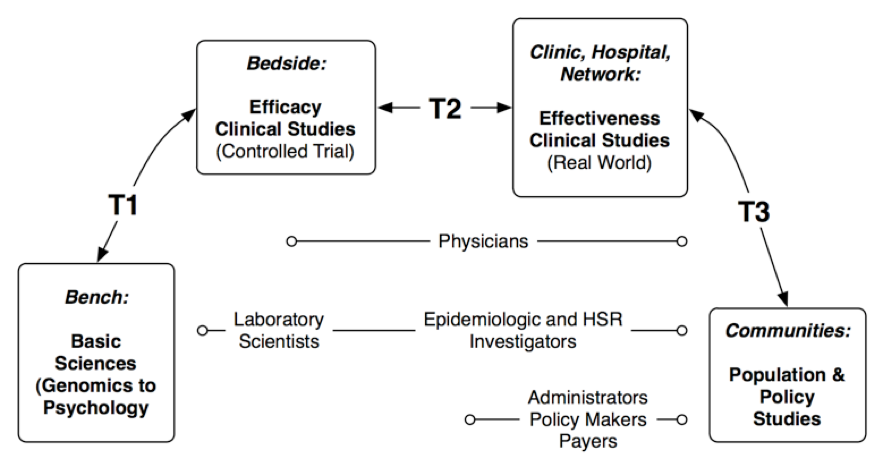

Through CE research, community members bring insight and local knowledge of community health problems to the table, while academic researchers bring an understanding of research design and study conduct. Community members help researchers prioritize research questions, identify appropriate research designs and interventions and interpret and disseminate findings to empower the community . This results in research findings that establish generalizable knowledge while being relevant to the context in which they are placed and, therefore, positioned to improve community health. In the lexicon of research phases, it is considered to be a T3 translational study.

It is exciting to see the growth in CE research since the founding of PolicyLab. Many PolicyLab investigators are turning to CE research designs to address questions of public health importance, including smoking cessation, obesity, school violence, racism, maternal depression and immigrant health to name a few. Understanding the importance of collaborative partnerships to develop sustainable solutions, my colleagues are developing projects that involve the local health department, advocacy organizations, schools and service providers.

Take as an example a project that I’m partnering on with Drs. Marsha Gerdes and Katherine Yun. We are working with members of the city of Philadelphia’s Division of Intellectual disAbility Services , KenCrest and Public Health Management Corporation to study the effects of patient navigation for children with developmental delays who have been referred to Early Intervention . Members of these community organizations have the intimate knowledge of how Philadelphia’s Infant Toddler Early Intervention Program works and are positioned to disseminate our research findings locally. It has been an empowering and fruitful partnership that is only increasing our ability to develop evidence-based sustainable solutions for these youth.

As we mark PolicyLab’s 10 th anniversary and think about charting new frontiers in children’s health policy, I expect that PolicyLab investigators will continue to rely on CE research to address difficult problems and to help improve the lives of Philadelphia’s children. I look forward to partnering with them and with our community partners on this exciting research.

Latest Blog Posts

Q&A: Engaging Communities to Alleviate Period Poverty with Lynette Medley

There are 16.9 million women, girls and all other people who experience a menstrual cycle in the United States living in poverty, many of whom are…

Supporting Early Literacy by Reaching Families Beyond the Exam Room Walls in 200 Words

March marks the celebration of National Reading Month! At PolicyLab and Reach Out and Read Greater Philadelphia (RORGP), we champion the role of…

Eating Disorders Affect Boys and Men Too—Research and Policy Need to Catch Up

A Google image search for “eating disorders” will return countless photos of young girls and women staring miserably at a plate or at the number on a…

Check out our new Publications View Publications

Adolescent Health & Well-Being

Behavioral health, population health sciences, health equity, family & community health.

A collaborative approach to community health issues

Asu college of health solutions celebrates 10 years of health innovation, looks forward.

Sometimes a good idea doesn’t have to be sold, it just needs the chance to be heard.

That’s how the idea behind Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions revealed itself to Dorothy Sears, the college’s executive director of clinical and community translational science and professor of nutrition.

As the College of Health Solutions celebrates its 10th anniversary, faculty, staff and alumni are reflecting on the history of the school while looking forward to what’s next.

The college was formed in 2012 when a group of separate academic units located across three campuses were brought together under one umbrella to offer students a comprehensive education in health.

In 2017, the new leader of the College of Health Solutions, Deborah Helitzer, was asked by ASU President Michael Crow to reimagine how those separate units could be better aligned to address the ASU Charter. That charter says that ASU must assume, among other things, fundamental responsibility for the overall health of the communities it serves.

With that charge, and a courageous changemaker at the helm, a collaborative process began to better align the college’s mission and structure with the university’s charter.

That idea appealed to Sears, who had a taste of a similar collaborative effort while working on a grant from the National Institutes of Health at a previous institution. The only problem was once that grant ran out, so did the spirit of collaboration.

But a chance meeting with College of Health Solutions Associate Dean and Professor Carol Johnston while Sears was on her way to a scientific conference in Mexico gave her an idea where she could find that collaborative spirit again.

Sears said, “While we flew down together, we just talked, talked and talked waiting for the plane and in line at customs and waiting to get bags. We had so much in common.”

Johnston later invited Sears to come to ASU to give a talk and she fell in love with the place.

“I was seeing the beautiful new facilities, that was the initial attraction; I wasn’t even considering leaving my (previous) institution at that point,” Sears said. “Then meeting (College of Health Solutions) Dean Deborah Helitzer was amazing. I felt like I had landed on another planet.

“Learning how the dean had led a process that resulted in eliminating all the departments in the college, I was like, wooo! This is awesome!”

College of Health Solutions Dean Deborah Helitzer (at podium) leads a visioning exercise shortly after arriving at Arizona State University in 2017.

A new approach to educating health leaders

The evolution of the College of Health Solutions was well underway by the time Sears came on board in 2018.

In 2012, Dr. Keith Lindor, former dean of the Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine, was named executive vice provost and founding dean of a newly formed College of Health Solutions. Lindor worked to create a new school for the science of health care delivery and strengthen the university’s partnership with Mayo Clinic.

The new health college also included previously existing academic units such as:

School of Nutrition and Health Promotion.

Department of Biomedical Informatics.

School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering.

Center for Health Innovation and Clinical Trials.

Center for Health Information and Research.

Center for World Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.

Health Care Delivery and Policy Program.

Healthcare Transformation Institute.

Those early years saw the college as a collection of health-related units and faculty with significant domain expertise who were spread out across three ASU campuses. Bringing that collection together to form a unified, integrated college would require significant change – change that might not be popular with everyone.

Julie Liss, now an associate dean and professor in the College of Health Solutions, came to ASU in 2013 as a professor in the former Department of Speech and Hearing Science, said that while some adapted to the change reluctantly, others embraced it.

“Other people were saying, ‘Wow, I’m meeting more people than I’ve ever known in the college, I’m able to do things I had never been able to do before,’” Liss said.

She said that accelerated when Helitzer was named dean of the College of Health Solutions in 2017.

“There were two eras,” Liss said. “The Dean Lindor era was getting all of our building blocks in place. The Dean Helitzer era was figuring out how those blocks could build something bigger, synergistically.”

Accelerating a rocket of change

Helitzer came to ASU from the University of New Mexico where she was the founding dean of the College of Population Health. While there, she led the development and implementation of the country’s first undergraduate degree in population health.

Her innovative work there caught the attention of ASU President Michael Crow. She was charged with leading the process of reimagining how the college could be positioned to best address major health issues in the community.

And she was asked to do it quickly.

Deborah Helitzer

“When President Crow introduced me to the faculty he said, ‘I told her I’m going to put her on a rocket and I’m expecting fast change,’” Helitzer said. “I said, ‘Well, President Crow, if you give me the fuel...' Everyone laughed and said, ‘We’re going to have to watch out for her.’”

In the fall of 2017 Helitzer assembled and led an executive visioning team working to reimagine what the college would become. That visioning project included ideas and input from 300 faculty, staff, administrators, community members and health system representatives. A new vision and structure emerged and Helitzer began leading the implementation of that vision, knocking down barriers to collaboration.

“There was no understanding of each other, no knowledge of each other,” Helitzer said. “The faculty were in the same physical building but didn’t know each other or talk to each other. We’ve worked to create structures to address that and we’re still working on it, but I’ve tried to put us on the path.”

One big idea that came out of the visioning effort is the formation of translational teams.

A unique approach to health solutions

Translational teams , a component of the new college structure, bring together researchers, teaching faculty, clinical and community partners, industry innovators and students with different skills and perspectives. By bringing all kinds of people together, translational teams aim to better understand the different layers of the problem they are trying to solve from the ground up. This translational approach takes advantage of the school’s work to break down barriers that have traditionally stopped faculty and students from different disciplines from working together.

It’s a holistic approach to solving the problems facing health care professionals and the essence of understanding the whole person, rather than specific diseases.

“You can look at the molecular level of a disease or condition,” Johnston said. “Then you can look at the dietary and exercise components. And then you can see how (that solution) can be introduced into a community to promote population health. You have all those fields going on. The translational piece is unique. I never heard of it until we started doing it.”

Translational teams at the College of Health Solutions are working on health problems including:

Autism spectrum disorder.

Cancer prevention and control.

Metabolic health.

Substance abuse.

They are studying the health needs of specific populations, such as women, children and those with significant health disparities, because those groups have special needs that are not experienced by other populations.

In addition to the creation of translational teams, the revisioning process also resulted in a charter for the College of Health Solutions.

That charter reads:

"The College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University is committed to translating scientific health research and discovery into practice. We prepare students to address the challenges facing our populations to stay healthy, improve their health and manage chronic disease. We bring people together to improve the health of the communities we serve, reaching them where they live, learn, work and play throughout the lifespan."

That statement helps to provide direction and focus, as well as some insight into the future of the College of Health Solutions. The college’s charter is directly aligned with the ASU Charter , specifically the last phrase, which mentions community health.

In the coming years, Helitzer sees the college being recognized as leading innovation in the field of health education, just as the university as a whole is recognized for innovation.

She would also like to see the college as having played an integral role in addressing the health needs of the community.

“It is critical that we work with the community to solve their problems, not what we see as their problems, but what they see as their problems,” Helitzer said. “That means our faculty must be nimble and will change or tweak what they’re doing to fit the needs of the community.”

Helitzer related that goal with something she experienced while working on malaria prevention in Africa. She said her group was talking to people about taking steps such as using bed nets and screens and ridding the area of standing water to control mosquitos.

“I remember going to one village and saying we want to help you with this,” she said. “They said, ‘First you get us running water and then we’ll be happy to talk with you about that.’ We worked on getting running water in the area and then they trusted us because that was what they needed. Then we could talk about malaria, which was also a problem for them, but it wasn’t the primary problem.”

Another outcome Helitzer would like to see as a result of the collaborative structure is for the students to gain a broader understanding of what the college has to offer and the many ways they can learn to make an impact.

“I’ve been saying we should have the first-year students have a course, or two semesters, to learn about all of the programs in the college and how we work together,” Helitzer said. “Then they could choose a major, knowing what role it plays in solving health problems.”

Helping students achieve their goals

Students are attracted to the forward-thinking, innovative nature of the College of Health Solutions, offering them a unique path toward meaningful change in health.

Vivienne Gellert, BS medical studies ’17, said her personal experience with health care shaped her views of the system and inspired her to take action. She said her education at the College of Health Solutions helped her reach those goals.

Gellert was badly injured in an automobile accident while she was in high school and saw first hand how frustrating and inefficient the system could be.

“You can ask anyone and they’ll tell you the health care system is broken,” Gellert said. “It’s easy to say that and get super frustrated with it, but at the end of the day, what are you going to do about it? In order to do something about it, we have to do something different and (the College of Health Solutions) prepared me to do just that.”