How to Write a Book Review: Awesome Guide

A book review allows students to illustrate the author's intentions of writing the piece, as well as create a criticism of the book — as a whole. In other words, form an opinion of the author's presented ideas. Check out this guide from EssayPro — book review writing service to learn how to write a book review successfully.

What Is a Book Review?

You may prosper, “what is a book review?”. Book reviews are commonly assigned students to allow them to show a clear understanding of the novel. And to check if the students have actually read the book. The essay format is highly important for your consideration, take a look at the book review format below.

Book reviews are assigned to allow students to present their own opinion regarding the author’s ideas included in the book or passage. They are a form of literary criticism that analyzes the author’s ideas, writing techniques, and quality. A book analysis is entirely opinion-based, in relevance to the book. They are good practice for those who wish to become editors, due to the fact, editing requires a lot of criticism.

Book Review Template

The book review format includes an introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Introduction

- Describe the book cover and title.

- Include any subtitles at this stage.

- Include the Author’s Name.

- Write a brief description of the novel.

- Briefly introduce the main points of the body in your book review.

- Avoid mentioning any opinions at this time.

- Use about 3 quotations from the author’s novel.

- Summarize the quotations in your own words.

- Mention your own point-of-view of the quotation.

- Remember to keep every point included in its own paragraph.

- In brief, summarize the quotations.

- In brief, summarize the explanations.

- Finish with a concluding sentence.

- This can include your final opinion of the book.

- Star-Rating (Optional).

Get Your BOOK REVIEW WRITTEN!

Simply send us your paper requirements, choose a writer and we’ll get it done.

How to Write a Book Review: Step-By-Step

Writing a book review is something that can be done with every novel. Book reviews can apply to all novels, no matter the genre. Some genres may be harder than others. On the other hand, the book review format remains the same. Take a look at these step-by-step instructions from our professional writers to learn how to write a book review in-depth.

Step 1: Planning

Create an essay outline which includes all of the main points you wish to summarise in your book analysis. Include information about the characters, details of the plot, and some other important parts of your chosen novel. Reserve a body paragraph for each point you wish to talk about.

Consider these points before writing:

- What is the plot of the book? Understanding the plot enables you to write an effective review.

- Is the plot gripping? Does the plot make you want to continue reading the novel? Did you enjoy the plot? Does it manage to grab a reader’s attention?

- Are the writing techniques used by the author effective? Does the writer imply factors in-between the lines? What are they?

- Are the characters believable? Are the characters logical? Does the book make the characters are real while reading?

- Would you recommend the book to anyone? The most important thing: would you tell others to read this book? Is it good enough? Is it bad?

- What could be better? Keep in mind the quotes that could have been presented better. Criticize the writer.

Step 2: Introduction

Presumably, you have chosen your book. To begin, mention the book title and author’s name. Talk about the cover of the book. Write a thesis statement regarding the fictitious story or non-fictional novel. Which briefly describes the quoted material in the book review.

Step 3: Body

Choose a specific chapter or scenario to summarise. Include about 3 quotes in the body. Create summaries of each quote in your own words. It is also encouraged to include your own point-of-view and the way you interpret the quote. It is highly important to have one quote per paragraph.

Step 4: Conclusion

Write a summary of the summarised quotations and explanations, included in the body paragraphs. After doing so, finish book analysis with a concluding sentence to show the bigger picture of the book. Think to yourself, “Is it worth reading?”, and answer the question in black and white. However, write in-between the lines. Avoid stating “I like/dislike this book.”

Step 5: Rate the Book (Optional)

After writing a book review, you may want to include a rating. Including a star-rating provides further insight into the quality of the book, to your readers. Book reviews with star-ratings can be more effective, compared to those which don’t. Though, this is entirely optional.

Count on the support of our cheap essay writing service . We process all your requests fast.

Dive into literary analysis with EssayPro . Our experts can help you craft insightful book reviews that delve deep into the themes, characters, and narratives of your chosen books. Enhance your understanding and appreciation of literature with us.

Writing Tips

Here is the list of tips for the book review:

- A long introduction can certainly lower one’s grade: keep the beginning short. Readers don’t like to read the long introduction for any essay style.

- It is advisable to write book reviews about fiction: it is not a must. Though, reviewing fiction can be far more effective than writing about a piece of nonfiction

- Avoid Comparing: avoid comparing your chosen novel with other books you have previously read. Doing so can be confusing for the reader.

- Opinion Matters: including your own point-of-view is something that is often encouraged when writing book reviews.

- Refer to Templates: a book review template can help a student get a clearer understanding of the required writing style.

- Don’t be Afraid to Criticize: usually, your own opinion isn’t required for academic papers below Ph.D. level. On the other hand, for book reviews, there’s an exception.

- Use Positivity: include a fair amount of positive comments and criticism.

- Review The Chosen Novel: avoid making things up. Review only what is presented in the chosen book.

- Enjoyed the book? If you loved reading the book, state it. Doing so makes your book analysis more personalized.

Writing a book review is something worth thinking about. Professors commonly assign this form of an assignment to students to enable them to express a grasp of a novel. Following the book review format is highly useful for beginners, as well as reading step-by-step instructions. Writing tips is also useful for people who are new to this essay type. If you need a book review or essay, ask our book report writing services ' write paper for me ' and we'll give you a hand asap!

We also recommend that everyone read the article about essay topics . It will help broaden your horizons in writing a book review as well as other papers.

Book Review Examples

Referring to a book review example is highly useful to those who wish to get a clearer understanding of how to review a book. Take a look at our examples written by our professional writers. Click on the button to open the book review examples and feel free to use them as a reference.

Book review

Kenneth Grahame’s ‘The Wind in the Willows’

Kenneth Grahame’s ‘The Wind in the Willows’ is a novel aimed at youngsters. The plot, itself, is not American humor, but that of Great Britain. In terms of sarcasm, and British-related jokes. The novel illustrates a fair mix of the relationships between the human-like animals, and wildlife. The narrative acts as an important milestone in post-Victorian children’s literature.

Book Review

Dr. John’s ‘Pollution’

Dr. John’s ‘Pollution’ consists of 3 major parts. The first part is all about the polluted ocean. The second being about the pollution of the sky. The third part is an in-depth study of how humans can resolve these issues. The book is a piece of non-fiction that focuses on modern-day pollution ordeals faced by both animals and humans on Planet Earth. It also focuses on climate change, being the result of the global pollution ordeal.

We can do your coursework writing for you if you still find it difficult to write it yourself. Send to our custom term paper writing service your requirements, choose a writer and enjoy your time.

Need To Write a Book Review But DON’T HAVE THE TIME

We’re here to do it for you. Our professionals are ready to help 24/7

How To Write A Book Review?

What to include in a book review, what is a book review, related articles.

.webp)

Book Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write a book review, a report or essay that offers a critical perspective on a text. It offers a process and suggests some strategies for writing book reviews.

What is a review?

A review is a critical evaluation of a text, event, object, or phenomenon. Reviews can consider books, articles, entire genres or fields of literature, architecture, art, fashion, restaurants, policies, exhibitions, performances, and many other forms. This handout will focus on book reviews. For a similar assignment, see our handout on literature reviews .

Above all, a review makes an argument. The most important element of a review is that it is a commentary, not merely a summary. It allows you to enter into dialogue and discussion with the work’s creator and with other audiences. You can offer agreement or disagreement and identify where you find the work exemplary or deficient in its knowledge, judgments, or organization. You should clearly state your opinion of the work in question, and that statement will probably resemble other types of academic writing, with a thesis statement, supporting body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Typically, reviews are brief. In newspapers and academic journals, they rarely exceed 1000 words, although you may encounter lengthier assignments and extended commentaries. In either case, reviews need to be succinct. While they vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features:

- First, a review gives the reader a concise summary of the content. This includes a relevant description of the topic as well as its overall perspective, argument, or purpose.

- Second, and more importantly, a review offers a critical assessment of the content. This involves your reactions to the work under review: what strikes you as noteworthy, whether or not it was effective or persuasive, and how it enhanced your understanding of the issues at hand.

- Finally, in addition to analyzing the work, a review often suggests whether or not the audience would appreciate it.

Becoming an expert reviewer: three short examples

Reviewing can be a daunting task. Someone has asked for your opinion about something that you may feel unqualified to evaluate. Who are you to criticize Toni Morrison’s new book if you’ve never written a novel yourself, much less won a Nobel Prize? The point is that someone—a professor, a journal editor, peers in a study group—wants to know what you think about a particular work. You may not be (or feel like) an expert, but you need to pretend to be one for your particular audience. Nobody expects you to be the intellectual equal of the work’s creator, but your careful observations can provide you with the raw material to make reasoned judgments. Tactfully voicing agreement and disagreement, praise and criticism, is a valuable, challenging skill, and like many forms of writing, reviews require you to provide concrete evidence for your assertions.

Consider the following brief book review written for a history course on medieval Europe by a student who is fascinated with beer:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600, investigates how women used to brew and sell the majority of ale drunk in England. Historically, ale and beer (not milk, wine, or water) were important elements of the English diet. Ale brewing was low-skill and low status labor that was complimentary to women’s domestic responsibilities. In the early fifteenth century, brewers began to make ale with hops, and they called this new drink “beer.” This technique allowed brewers to produce their beverages at a lower cost and to sell it more easily, although women generally stopped brewing once the business became more profitable.

The student describes the subject of the book and provides an accurate summary of its contents. But the reader does not learn some key information expected from a review: the author’s argument, the student’s appraisal of the book and its argument, and whether or not the student would recommend the book. As a critical assessment, a book review should focus on opinions, not facts and details. Summary should be kept to a minimum, and specific details should serve to illustrate arguments.

Now consider a review of the same book written by a slightly more opinionated student:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 was a colossal disappointment. I wanted to know about the rituals surrounding drinking in medieval England: the songs, the games, the parties. Bennett provided none of that information. I liked how the book showed ale and beer brewing as an economic activity, but the reader gets lost in the details of prices and wages. I was more interested in the private lives of the women brewsters. The book was divided into eight long chapters, and I can’t imagine why anyone would ever want to read it.

There’s no shortage of judgments in this review! But the student does not display a working knowledge of the book’s argument. The reader has a sense of what the student expected of the book, but no sense of what the author herself set out to prove. Although the student gives several reasons for the negative review, those examples do not clearly relate to each other as part of an overall evaluation—in other words, in support of a specific thesis. This review is indeed an assessment, but not a critical one.

Here is one final review of the same book:

One of feminism’s paradoxes—one that challenges many of its optimistic histories—is how patriarchy remains persistent over time. While Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 recognizes medieval women as historical actors through their ale brewing, it also shows that female agency had its limits with the advent of beer. I had assumed that those limits were religious and political, but Bennett shows how a “patriarchal equilibrium” shut women out of economic life as well. Her analysis of women’s wages in ale and beer production proves that a change in women’s work does not equate to a change in working women’s status. Contemporary feminists and historians alike should read Bennett’s book and think twice when they crack open their next brewsky.

This student’s review avoids the problems of the previous two examples. It combines balanced opinion and concrete example, a critical assessment based on an explicitly stated rationale, and a recommendation to a potential audience. The reader gets a sense of what the book’s author intended to demonstrate. Moreover, the student refers to an argument about feminist history in general that places the book in a specific genre and that reaches out to a general audience. The example of analyzing wages illustrates an argument, the analysis engages significant intellectual debates, and the reasons for the overall positive review are plainly visible. The review offers criteria, opinions, and support with which the reader can agree or disagree.

Developing an assessment: before you write

There is no definitive method to writing a review, although some critical thinking about the work at hand is necessary before you actually begin writing. Thus, writing a review is a two-step process: developing an argument about the work under consideration, and making that argument as you write an organized and well-supported draft. See our handout on argument .

What follows is a series of questions to focus your thinking as you dig into the work at hand. While the questions specifically consider book reviews, you can easily transpose them to an analysis of performances, exhibitions, and other review subjects. Don’t feel obligated to address each of the questions; some will be more relevant than others to the book in question.

- What is the thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world you know? What has the book accomplished?

- What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? What is the approach to the subject (topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive)?

- How does the author support their argument? What evidence do they use to prove their point? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author’s information (or conclusions) conflict with other books you’ve read, courses you’ve taken or just previous assumptions you had of the subject?

- How does the author structure their argument? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- How has this book helped you understand the subject? Would you recommend the book to your reader?

Beyond the internal workings of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the circumstances of the text’s production:

- Who is the author? Nationality, political persuasion, training, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the biographer was the subject’s best friend? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they write about?

- What is the book’s genre? Out of what field does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or literary standard on which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know. Keep in mind, though, that naming “firsts”—alongside naming “bests” and “onlys”—can be a risky business unless you’re absolutely certain.

Writing the review

Once you have made your observations and assessments of the work under review, carefully survey your notes and attempt to unify your impressions into a statement that will describe the purpose or thesis of your review. Check out our handout on thesis statements . Then, outline the arguments that support your thesis.

Your arguments should develop the thesis in a logical manner. That logic, unlike more standard academic writing, may initially emphasize the author’s argument while you develop your own in the course of the review. The relative emphasis depends on the nature of the review: if readers may be more interested in the work itself, you may want to make the work and the author more prominent; if you want the review to be about your perspective and opinions, then you may structure the review to privilege your observations over (but never separate from) those of the work under review. What follows is just one of many ways to organize a review.

Introduction

Since most reviews are brief, many writers begin with a catchy quip or anecdote that succinctly delivers their argument. But you can introduce your review differently depending on the argument and audience. The Writing Center’s handout on introductions can help you find an approach that works. In general, you should include:

- The name of the author and the book title and the main theme.

- Relevant details about who the author is and where they stand in the genre or field of inquiry. You could also link the title to the subject to show how the title explains the subject matter.

- The context of the book and/or your review. Placing your review in a framework that makes sense to your audience alerts readers to your “take” on the book. Perhaps you want to situate a book about the Cuban revolution in the context of Cold War rivalries between the United States and the Soviet Union. Another reviewer might want to consider the book in the framework of Latin American social movements. Your choice of context informs your argument.

- The thesis of the book. If you are reviewing fiction, this may be difficult since novels, plays, and short stories rarely have explicit arguments. But identifying the book’s particular novelty, angle, or originality allows you to show what specific contribution the piece is trying to make.

- Your thesis about the book.

Summary of content

This should be brief, as analysis takes priority. In the course of making your assessment, you’ll hopefully be backing up your assertions with concrete evidence from the book, so some summary will be dispersed throughout other parts of the review.

The necessary amount of summary also depends on your audience. Graduate students, beware! If you are writing book reviews for colleagues—to prepare for comprehensive exams, for example—you may want to devote more attention to summarizing the book’s contents. If, on the other hand, your audience has already read the book—such as a class assignment on the same work—you may have more liberty to explore more subtle points and to emphasize your own argument. See our handout on summary for more tips.

Analysis and evaluation of the book

Your analysis and evaluation should be organized into paragraphs that deal with single aspects of your argument. This arrangement can be challenging when your purpose is to consider the book as a whole, but it can help you differentiate elements of your criticism and pair assertions with evidence more clearly. You do not necessarily need to work chronologically through the book as you discuss it. Given the argument you want to make, you can organize your paragraphs more usefully by themes, methods, or other elements of the book. If you find it useful to include comparisons to other books, keep them brief so that the book under review remains in the spotlight. Avoid excessive quotation and give a specific page reference in parentheses when you do quote. Remember that you can state many of the author’s points in your own words.

Sum up or restate your thesis or make the final judgment regarding the book. You should not introduce new evidence for your argument in the conclusion. You can, however, introduce new ideas that go beyond the book if they extend the logic of your own thesis. This paragraph needs to balance the book’s strengths and weaknesses in order to unify your evaluation. Did the body of your review have three negative paragraphs and one favorable one? What do they all add up to? The Writing Center’s handout on conclusions can help you make a final assessment.

Finally, a few general considerations:

- Review the book in front of you, not the book you wish the author had written. You can and should point out shortcomings or failures, but don’t criticize the book for not being something it was never intended to be.

- With any luck, the author of the book worked hard to find the right words to express her ideas. You should attempt to do the same. Precise language allows you to control the tone of your review.

- Never hesitate to challenge an assumption, approach, or argument. Be sure, however, to cite specific examples to back up your assertions carefully.

- Try to present a balanced argument about the value of the book for its audience. You’re entitled—and sometimes obligated—to voice strong agreement or disagreement. But keep in mind that a bad book takes as long to write as a good one, and every author deserves fair treatment. Harsh judgments are difficult to prove and can give readers the sense that you were unfair in your assessment.

- A great place to learn about book reviews is to look at examples. The New York Times Sunday Book Review and The New York Review of Books can show you how professional writers review books.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Drewry, John. 1974. Writing Book Reviews. Boston: Greenwood Press.

Hoge, James. 1987. Literary Reviewing. Charlottesville: University Virginia of Press.

Sova, Dawn, and Harry Teitelbaum. 2002. How to Write Book Reports , 4th ed. Lawrenceville, NY: Thomson/Arco.

Walford, A.J. 1986. Reviews and Reviewing: A Guide. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Reading a book to review it

Choose your book carefully.

Being interested in a book will help you write a strong review, so take some time to choose a book whose topic and scholarly approach genuinely interest you.

If you’re assigned a book, you’ll need to find a way to become interested in it.

Read actively and critically

Don’t read just to discover the author’s main point or to mine some facts.

Engage with the text, marking important points and underlining passages as you go along (in books you own, of course!).

Focus first on summary and analysis

Before you read

- Write down quickly and informally some of the facts and ideas you already know about the book’s topic

- Survey the book –including the preface and table of contents–and make some predictions

- What does the title promise the book will cover or argue?

- What does the preface promise about the book?

- What does the table of contents tell you about how the book is organized?

- Who’s the audience for this book?

As you read

With individual chapters:

- Think carefully about the chapter’s title and skim paragraphs to get an overall sense of the chapter.

- Then, as you read, test your predictions against the points made in the chapter.

- After you’ve finished a chapter, take brief notes. Start by summarizing , in your own words, the major points of the chapter. Then you might want to take brief notes about particular passages you might discuss in your review.

Begin to evaluate

As you take notes about the book, try dividing your page into two columns. In the left, summarize main points from a chapter. In the right, record your reactions to and your tentative evaluations of that chapter.

Here are several ways you can evaluate a book:

- If you know other books on this same subject, you can compare the arguments and quality of the book you’re reviewing with the others, emphasizing what’s new and what’s especially valuable in the book you’re reviewing.

- How well does the book fulfill the promises the author makes in the preface and introduction?

- How effective is the book’s methodology?

- How effectively does the book make its arguments?

- How persuasive is the evidence?

- For its audience, what are the book’s strengths?

- How clearly is the book written?

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide and Examples

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Chapter Summary

Chapter summary is a brief overview of the key points or events covered in a specific chapter of a book, academic paper, or other written work. It typically includes a concise description of the main ideas, arguments, or themes explored in the chapter, as well as any important supporting details or evidence .

Chapter summaries are often used as study aids, providing readers with a quick way to review and understand the content of a particular section of a longer work. They may also be included as part of a book’s table of contents or used as a promotional tool to entice potential readers.

How to Write Chapter Summary

Writing a chapter summary involves condensing the content of a chapter into a shorter, more concise form while still retaining its essential meaning. Here are some steps to help you write a chapter summary:

- Read the chapter carefully: Before summarizing a chapter, it is important to read it thoroughly to ensure that you understand the main ideas and points being made.

- Identify the main ideas: Identify the main ideas and arguments that the chapter is presenting. These may be explicit, or they may be implicit and require some interpretation on your part.

- Make notes: Take notes while reading to help you keep track of the main ideas and arguments. Write down key phrases, important quotes, and any examples or evidence that support the main points.

- Create an outline : Once you have identified the main ideas and arguments, create an outline for your summary. This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure that you include all the important points.

- Write the summary : Using your notes and outline, write a summary of the chapter. Start with a brief introduction that provides context for the chapter, then summarize the main ideas and arguments, and end with a conclusion that ties everything together.

- Edit and revise: After you have written the summary, review it carefully to ensure that it is accurate and concise. Make any necessary edits or revisions to improve the clarity and readability of the summary.

- Check for plagiarism : Finally, check your summary for plagiarism. Make sure that you have not copied any content directly from the chapter without proper citation.

Chapter Summary in Research Paper

In a Research Paper , a Chapter Summary is a brief description of the main points or findings covered in a particular chapter. The summary is typically included at the beginning or end of each chapter and serves as a guide for the reader to quickly understand the content of that chapter.

Here is an example of a chapter summary from a research paper on climate change:

Chapter 2: The Science of Climate Change

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the scientific consensus on climate change. We begin by discussing the greenhouse effect and the role of greenhouse gases in trapping heat in the atmosphere. We then review the evidence for climate change, including temperature records, sea level rise, and changes in the behavior of plants and animals. Finally, we examine the potential impacts of climate change on human society and the natural world. Overall, this chapter provides a foundation for understanding the scientific basis for climate change and the urgency of taking action to address this global challenge.

Chapter Summary in Thesis

In a Thesis , the Chapter Summary is a section that provides a brief overview of the main points covered in each chapter of the thesis. It is usually included at the beginning or end of each chapter and is intended to help the reader understand the key concepts and ideas presented in the chapter.

For example, in a thesis on computer science field, a chapter summary for a chapter on “Machine Learning Algorithms” might include:

Chapter 3: Machine Learning Algorithms

This chapter explores the use of machine learning algorithms in solving complex problems in computer science. We begin by discussing the basics of machine learning, including supervised and unsupervised learning, as well as different types of algorithms such as decision trees, neural networks, and support vector machines. We then present a case study on the application of machine learning algorithms in image recognition, demonstrating how these algorithms can improve accuracy and reduce error rates. Finally, we discuss the limitations and challenges of using machine learning algorithms, including issues of bias and overfitting. Overall, this chapter highlights the potential of machine learning algorithms to revolutionize the field of computer science and drive innovation in a wide range of industries.

Examples of Chapter Summary

Some Examples of Chapter Summary are as follows:

Research Title: “The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health: A Review of the Literature”

Chapter Summary:

Chapter 1: Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the research problem, which is the impact of social media on mental health. It presents the purpose of the study, the research questions, and the methodology used to conduct the research.

Research Title : “The Effects of Exercise on Cognitive Functioning in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis”

Chapter 2: Literature Review

This chapter reviews the existing literature on the effects of exercise on cognitive functioning in older adults. It provides an overview of the theoretical framework and previous research findings related to the topic. The chapter concludes with a summary of the research gaps and limitations.

Research Title: “The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Leadership Effectiveness: A Case Study of Successful Business Leaders”

Chapter 3: Methodology

This chapter presents the research methodology used in the study, which is a case study approach. It describes the selection criteria for the participants and the data collection methods used. The chapter also provides a detailed explanation of the data analysis techniques used in the study.

Research Title: “Factors Influencing Employee Engagement in the Workplace: A Systematic Review”

Chapter 4: Results and Discussion

This chapter presents the findings of the systematic review on the factors influencing employee engagement in the workplace. It provides a detailed analysis of the results, including the strengths and limitations of the studies reviewed. The chapter also discusses the implications of the findings for practice and future research.

Purpose of Chapter Summary

Some Purposes of the Chapter Summary are as follows:

- Comprehension : A chapter summary can help readers understand the main points of a chapter or book. It can help readers remember important details, keep track of the plot or argument, and connect the key ideas.

- Review : A chapter summary can be a useful tool for reviewing the material covered in a chapter. It can help readers review the content quickly and efficiently, and it can also serve as a reference for future study.

- Study aid: A chapter summary can be used as a study aid, especially for students who are preparing for exams or writing papers. It can help students organize their thoughts and focus on the most important information.

- Teaching tool: A chapter summary can be a useful teaching tool for educators. It can help teachers introduce key concepts and ideas, facilitate class discussion, and assess student understanding.

- Communication : A chapter summary can be used as a way to communicate the main ideas of a chapter or book to others. It can be used in presentations, reports, and other forms of communication to convey important information quickly and concisely.

- Time-saving : A chapter summary can save time for busy readers who may not have the time to read an entire book or chapter in detail. By providing a brief overview of the main points, a chapter summary can help readers determine whether a book or chapter is worth further reading.

- Accessibility : A chapter summary can make complex or technical information more accessible to a wider audience. It can help break down complex ideas into simpler terms and provide a clear and concise explanation of key concepts.

- Analysis : A chapter summary can be used as a starting point for analysis and discussion. It can help readers identify themes, motifs, and other literary devices used in the chapter or book, and it can serve as a jumping-off point for further analysis.

- Personal growth : A chapter summary can be used for personal growth and development. It can help readers gain new insights, learn new skills, and develop a deeper understanding of the world around them.

When to Write Chapter Summary

Chapter summaries are usually written after you have finished reading a chapter or a book. Writing a chapter summary can be useful for several reasons, including:

- Retention : Summarizing a chapter helps you to better retain the information you have read.

- Studying : Chapter summaries can be a useful study tool when preparing for exams or writing papers.

- Review : When you need to review a book or chapter quickly, a summary can help you to refresh your memory.

- Analysis : Summarizing a chapter can help you to identify the main themes and ideas of a book, which can be useful when analyzing it.

Advantages of Chapter Summary

Chapter summaries have several advantages:

- Helps with retention : Summarizing the key points of a chapter can help you remember important information better. By condensing the information, you can identify the main ideas and focus on the most relevant points.

- Saves time : Instead of re-reading the entire chapter when you need to review information, a summary can help you quickly refresh your memory. It can also save time during note-taking and studying.

- Provides an overview : A summary can give you a quick overview of the chapter’s content and help you identify the main themes and ideas. This can help you understand the broader context of the material.

- Helps with comprehension : Summarizing the content of a chapter can help you better understand the material. It can also help you identify any areas where you might need more clarification or further study.

- Useful for review: Chapter summaries can be a useful review tool before exams or when writing papers. They can help you organize your thoughts and review key concepts and ideas.

- Facilitates discussion: When working in a group, chapter summaries can help facilitate discussion and ensure that everyone is on the same page. It can also help to identify areas of confusion or disagreement.

- Supports active reading : Creating a summary requires active reading, which means that you are engaging with the material and thinking critically about it. This can help you develop stronger reading and critical thinking skills.

- Enables comparison : When reading multiple sources on a topic, creating summaries of each chapter can help you compare and contrast the information presented. This can help you identify differences and similarities in the arguments and ideas presented.

- Helpful for long texts: In longer books or texts, chapter summaries can be especially helpful. They can help you break down the material into manageable chunks and make it easier to digest.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

7 Steps of Writing an Excellent Academic Book Chapter

Writing is an inextricable part of an academic’s career; maintaining lab reports, writing personal statements, drafting cover letters, research proposals, the dissertation—this list goes on. However, while these are considered as essentials during any research program, writing an academic book is a milestone every writer aims to achieve. It could either be your urge of authoring a book or you may have received an invite from a publisher to write a book chapter . In both cases, most researchers find it difficult to write an academic book chapter.

The questions that may arise when you plan on writing a book chapter are:

- Where do I start from?

- How do I even do this?

- What should be the length of book chapters?

- How should I link one chapter to the following chapter?

These questions are quite common when starting with your first book chapter. In this article, we’ll discuss the steps on how to write an excellent academic book chapter.

Table of Contents

What is an Academic Book Chapter?

An academic book chapter is defined as a section, or division, of a book. These are usually separated with a chapter number or title. A chapter divides the overall book topic into topic-specific sections. Furthermore, each chapter in a book is related to the overall theme of the book.

A book chapter allows the author to divide their work in parts for readers to understand and remember it easily. Additionally, chapters help create structure in your writing for a better flow of ideas.

How Long Should a Book Chapter be?

Typically, a non-fiction book chapter should be small and must only include information related to one major idea. However, since a non-fiction /academic book is around 50,000 to 70,000 words, and each book would comprise 10-20 chapters, each book chapter’s word limit should range between 3500 and 7000 words.

While there aren’t any standard rules to follow with respect to the length of a book chapter, it may vary depending on the genre of your writing. However, it is better to refer your publisher’s guidelines and write your chapters accordingly.

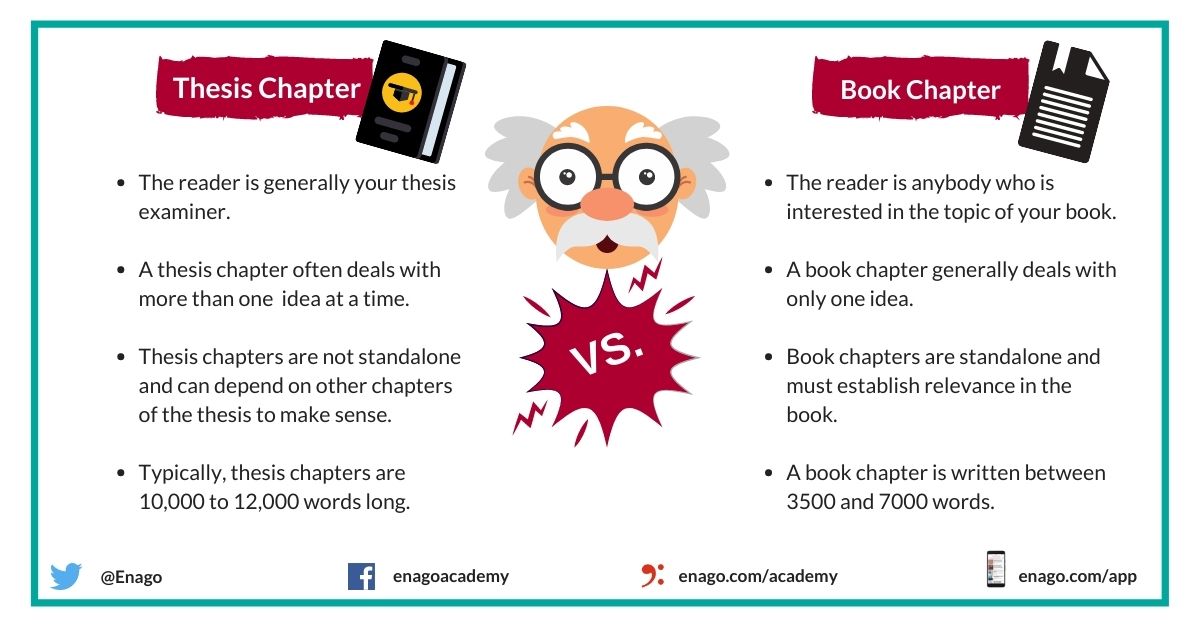

Difference between a Book Chapter and Thesis Chapter

What makes a book excellent are the book chapters that it comprises. Thus, the key to writing an excellent book is mastering the art of writing a book chapter . You’d think you could write a book easily because you’ve already written your dissertation. However, writing a book chapter is not the same as writing your thesis.

The image below shares 5 major differences between a book chapter and a thesis chapter:

How to Write a Book Chapter?

As writing a book chapter is the first milestone in your writing journey, it can be overwhelming and difficult to garner your thoughts and put them down on a sheet at once. It takes time and effort to gain momentum for accomplishing this mammoth task. However, proper planning followed by dedicated effort will make you realize that you were worrying over something trivial.

So let us make the process of writing a book chapter easier with these 7 steps.

Step 1: Collate Relevant Information

How would you even start writing a chapter if you do not have the necessary information or data? The first step even before you start writing is to review and collate all the relevant data that is necessary to formulate an informative chapter.

Since a chapter focuses on one major idea it should not include any gaps that perplexes the reader. Creating mind-maps help in linking different sources of information and compiling them to formulate a completely new chapter. As a result, you can structure your ideas to help with your analysis and see it visually. This process improves your understanding of the book’s theme. More importantly, sort the ideas into a logical order of how you should present them in your chapter. This makes it easier to write the chapter without convoluting it.

Step 2: Design the Chapter Structure

After spending hours in brainstorming ideas and understanding the fundamentals that the chapter should cover, you must create a structured outline. Furthermore, following a standard format helps you stay on track and structure your chapter fluently.

Ideally, a well-structured chapter includes the following elements:

- A title or heading

- An interesting introduction

- Main body informative paragraphs

- A summary of the chapter

- Smooth transition to the next chapter

Even so, you may not restrict yourself to following only one structure; rather, add more or less to each of your chapters depending on your genre, writing style, and requirement of the chapter to maintain the book’s overall theme. Keep only relevant content in your chapter. Avoid content that causes the reader to go off on a tangent.

Step 3: Write an Appealing Chapter Title/Heading

How often have you put a book back on the book store’s shelf right after reading its title? Didn’t even bother to read the synopsis, did you? Likewise, you may have written the most impactful chapter, but what sense would it make if its title is not interesting enough. An impactful chapter title captures the reader’s attention. It’s basically the “first sight” rule!

Your chapter’s title/heading must trigger curiosity in the reader and make them want to read and learn more. Although this is the first element of a chapter, most writers find it easier to create a title/heading after completing the chapter.

Step 4: Build an Engaging Introduction

Now that you have captured the reader’s attention with your title/heading, it has obviously increased the readers’ expectations from the content. To keep them interested in your chapter, write an introduction that keeps them hooked on. You may use a narrative approach or build a fictional plot to grab the attention of the reader. However, ensure that you do not deviate from the main context of your chapter. Finally, writing an effective introduction will help you in presenting an overview of your chapter.

Some of the tricks to follow when writing an exceptional introduction are:

- Share an anecdote

- Create a dialogue or conversation

- Include quotations

- Create a fictional plot

Step 5: Elaborate on Main Points of the Chapter

Impactful title? Checked!

Interesting introduction? Checked!

Now is the time to dive in to the details imparting section of the chapter. Expand your opening statement and begin to explain your points in detail. More importantly, leave no space for speculation in the reader’s mind.

This section should answer the following questions of the reader:

- Why has the reader chosen to read your book?

- What do they need to know?

- Are their questions and doubts being resolved with the content of your chapter?

Ensure that you build each point coherently and follow a cohesive flow. Furthermore, provide statistical data, evidence-based information, experimental data, graphical presentations, etc. You could formulate these points into 4-5 paragraphs based on the details of your chapter. To ensure you structure these details coherently across the right number of paragraphs, calculate the number of paragraphs in your text here .

Step 6: Summarize the Chapter

As impactful was the entry, so should be the exit, right? The summary is the part where you are almost done. This section is a key takeaway for your readers. So, revisit your chapter’s main content and summarize it. Since your chapter has given a lot of information, you’d want the reader to remember the gist of it as they reach the end of your chapter. Hence, writing a concise summary that constitutes the crux of your chapter is imperative.

Step 7: Add a Call-to-Action & Transition to Next Chapter

This section comes at the extreme end of the book chapter, when you ask the reader to implement the learnings from the chapter. It is a way of applying their newly acquired knowledge. In this section, you can also add a transition from your chapter to the succeeding chapter.

So would you still have jitters while writing your book chapter? Are there any other strategies or steps that you follow to write one? Let us know in the comments section below on how these steps helped you in writing a book chapter .

Thank you I have got a full lecture for sure

Thank for the encouraging words

You have demystified the act of writing a book chapter. Thank you for your efforts.

Very informative

It has really helpful for beginners like me.

Very impactful and informative. Thank you 😊

Very informative and helpful to beginners like us. Thank you.

Thanks for this very informative article

You have made writing a book chapter seem very simple. I appreciate all of your hard work.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- AI in Academia

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Reporting Research

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

Being a Research Blogger: The art of making an impact on the academic audience with…

Statement of Purpose Vs. Personal Statement – A Guide for Early Career…

When Your Thesis Advisor Asks You to Quit

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A book review is a thorough description, critical analysis, and/or evaluation of the quality, meaning, and significance of a book, often written in relation to prior research on the topic. Reviews generally range from 500-2000 words, but may be longer or shorter depends on several factors: the length and complexity of the book being reviewed, the overall purpose of the review, and whether the review examines two or more books that focus on the same topic. Professors assign book reviews as practice in carefully analyzing complex scholarly texts and to assess your ability to effectively synthesize research so that you reach an informed perspective about the topic being covered.

There are two general approaches to reviewing a book:

- Descriptive review: Presents the content and structure of a book as objectively as possible, describing essential information about a book's purpose and authority. This is done by stating the perceived aims and purposes of the study, often incorporating passages quoted from the text that highlight key elements of the work. Additionally, there may be some indication of the reading level and anticipated audience.

- Critical review: Describes and evaluates the book in relation to accepted literary and historical standards and supports this evaluation with evidence from the text and, in most cases, in contrast to and in comparison with the research of others. It should include a statement about what the author has tried to do, evaluates how well you believe the author has succeeded in meeting the objectives of the study, and presents evidence to support this assessment. For most course assignments, your professor will want you to write this type of review.

Book Reviews. Writing Center. University of New Hampshire; Book Reviews: How to Write a Book Review. Writing and Style Guides. Libraries. Dalhousie University; Kindle, Peter A. "Teaching Students to Write Book Reviews." Contemporary Rural Social Work 7 (2015): 135-141; Erwin, R. W. “Reviewing Books for Scholarly Journals.” In Writing and Publishing for Academic Authors . Joseph M. Moxley and Todd Taylor. 2 nd edition. (Lanham, MD: Rowan and Littlefield, 1997), pp. 83-90.

How to Approach Writing Your Review

NOTE: Since most course assignments require that you write a critical rather than descriptive book review, the following information about preparing to write and developing the structure and style of reviews focuses on this approach.

I. Common Features

While book reviews vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features. These include:

- A review gives the reader a concise summary of the content . This includes a description of the research topic and scope of analysis as well as an overview of the book's overall perspective, argument, and purpose.

- A review offers a critical assessment of the content in relation to other studies on the same topic . This involves documenting your reactions to the work under review--what strikes you as noteworthy or important, whether or not the arguments made by the author(s) were effective or persuasive, and how the work enhanced your understanding of the research problem under investigation.

- In addition to analyzing a book's strengths and weaknesses, a scholarly review often recommends whether or not readers would value the work for its authenticity and overall quality . This measure of quality includes both the author's ideas and arguments and covers practical issues, such as, readability and language, organization and layout, indexing, and, if needed, the use of non-textual elements .

To maintain your focus, always keep in mind that most assignments ask you to discuss a book's treatment of its topic, not the topic itself . Your key sentences should say, "This book shows...,” "The study demonstrates...," or “The author argues...," rather than "This happened...” or “This is the case....”

II. Developing a Critical Assessment Strategy

There is no definitive methodological approach to writing a book review in the social sciences, although it is necessary that you think critically about the research problem under investigation before you begin to write. Therefore, writing a book review is a three-step process: 1) carefully taking notes as you read the text; 2) developing an argument about the value of the work under consideration; and, 3) clearly articulating that argument as you write an organized and well-supported assessment of the work.

A useful strategy in preparing to write a review is to list a set of questions that should be answered as you read the book [remember to note the page numbers so you can refer back to the text!]. The specific questions to ask yourself will depend upon the type of book you are reviewing. For example, a book that is presenting original research about a topic may require a different set of questions to ask yourself than a work where the author is offering a personal critique of an existing policy or issue.

Here are some sample questions that can help you think critically about the book:

- Thesis or Argument . What is the central thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one main idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world that you know or have experienced? What has the book accomplished? Is the argument clearly stated and does the research support this?

- Topic . What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Is it clearly articulated? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? Can you detect any biases? What type of approach has the author adopted to explore the research problem [e.g., topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive]?

- Evidence . How does the author support their argument? What evidence does the author use to prove their point? Is the evidence based on an appropriate application of the method chosen to gather information? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author's information [or conclusions] conflict with other books you've read, courses you've taken, or just previous assumptions you had about the research problem?

- Structure . How does the author structure their argument? Does it follow a logical order of analysis? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense to you? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- Take-aways . How has this book helped you understand the research problem? Would you recommend the book to others? Why or why not?

Beyond the content of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the general presentation of information. Question to ask may include:

- The Author: Who is the author? The nationality, political persuasion, education, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the author is affiliated with a particular organization? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they wrote about? What other topics has the author written about? Does this work build on prior research or does it represent a new or unique area of research?

- The Presentation: What is the book's genre? Out of what discipline does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or other contextual standard upon which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know this. Keep in mind, though, that declarative statements about being the “first,” the "best," or the "only" book of its kind can be a risky unless you're absolutely certain because your professor [presumably] has a much better understanding of the overall research literature.

NOTE: Most critical book reviews examine a topic in relation to prior research. A good strategy for identifying this prior research is to examine sources the author(s) cited in the chapters introducing the research problem and, of course, any review of the literature. However, you should not assume that the author's references to prior research is authoritative or complete. If any works related to the topic have been excluded, your assessment of the book should note this . Be sure to consult with a librarian to ensure that any additional studies are located beyond what has been cited by the author(s).

Book Reviews. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Book Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Hartley, James. "Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (July 2006): 1194–1207; Motta-Roth, D. “Discourse Analysis and Academic Book Reviews: A Study of Text and Disciplinary Cultures.” In Genre Studies in English for Academic Purposes . Fortanet Gómez, Inmaculada et al., editors. (Castellò de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, 1998), pp. 29-45. Writing a Book Review. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Book Reviews. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Suárez, Lorena and Ana I. Moreno. “The Rhetorical Structure of Academic Journal Book Reviews: A Cross-linguistic and Cross-disciplinary Approach .” In Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, María del Carmen Pérez Llantada Auría, Ramón Plo Alastrué, and Claus Peter Neumann. Actas del V Congreso Internacional AELFE/Proceedings of the 5th International AELFE Conference . Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza, 2006.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Bibliographic Information

Bibliographic information refers to the essential elements of a work if you were to cite it in a paper [i.e., author, title, date of publication, etc.]. Provide the essential information about the book using the writing style [e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago] preferred by your professor or used by the discipline of your major . Depending on how your professor wants you to organize your review, the bibliographic information represents the heading of your review. In general, it would look like this:

[Complete title of book. Author or authors. Place of publication. Publisher. Date of publication. Number of pages before first chapter, often in Roman numerals. Total number of pages]. The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party's Revolution and the Battle over American History . By Jill Lepore. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. xii, 207 pp.)

Reviewed by [your full name].

II. Scope/Purpose/Content

Begin your review by telling the reader not only the overarching concern of the book in its entirety [the subject area] but also what the author's particular point of view is on that subject [the thesis statement]. If you cannot find an adequate statement in the author's own words or if you find that the thesis statement is not well-developed, then you will have to compose your own introductory thesis statement that does cover all the material. This statement should be no more than one paragraph and must be succinctly stated, accurate, and unbiased.

If you find it difficult to discern the overall aims and objectives of the book [and, be sure to point this out in your review if you determine that this is a deficiency], you may arrive at an understanding of the book's overall purpose by assessing the following:

- Scan the table of contents because it can help you understand how the book was organized and will aid in determining the author's main ideas and how they were developed [e.g., chronologically, topically, historically, etc.].

- Why did the author write on this subject rather than on some other subject?

- From what point of view is the work written?

- Was the author trying to give information, to explain something technical, or to convince the reader of a belief’s validity by dramatizing it in action?

- What is the general field or genre, and how does the book fit into it? If necessary, review related literature from other books and journal articles to familiarize yourself with the field.

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author's style? Is it formal or informal? You can evaluate the quality of the writing style by noting some of the following standards: coherence, clarity, originality, forcefulness, accurate use of technical words, conciseness, fullness of development, and fluidity [i.e., quality of the narrative flow].

- How did the book affect you? Were there any prior assumptions you had about the subject that were changed, abandoned, or reinforced after reading the book? How is the book related to your own personal beliefs or assumptions? What personal experiences have you had related to the subject that affirm or challenge underlying assumptions?

- How well has the book achieved the goal(s) set forth in the preface, introduction, and/or foreword?

- Would you recommend this book to others? Why or why not?

III. Note the Method

Support your remarks with specific references to text and quotations that help to illustrate the literary method used to state the research problem, describe the research design, and analyze the findings. In general, authors tend to use the following literary methods, exclusively or in combination.

- Description : The author depicts scenes and events by giving specific details that appeal to the five senses, or to the reader’s imagination. The description presents background and setting. Its primary purpose is to help the reader realize, through as many details as possible, the way persons, places, and things are situated within the phenomenon being described.

- Narration : The author tells the story of a series of events, usually thematically or in chronological order. In general, the emphasis in scholarly books is on narration of the events. Narration tells what has happened and, in some cases, using this method to forecast what could happen in the future. Its primary purpose is to draw the reader into a story and create a contextual framework for understanding the research problem.

- Exposition : The author uses explanation and analysis to present a subject or to clarify an idea. Exposition presents the facts about a subject or an issue clearly and as impartially as possible. Its primary purpose is to describe and explain, to document for the historical record an event or phenomenon.

- Argument : The author uses techniques of persuasion to establish understanding of a particular truth, often in the form of addressing a research question, or to convince the reader of its falsity. The overall aim is to persuade the reader to believe something and perhaps to act on that belief. Argument takes sides on an issue and aims to convince the reader that the author's position is valid, logical, and/or reasonable.

IV. Critically Evaluate the Contents

Critical comments should form the bulk of your book review . State whether or not you feel the author's treatment of the subject matter is appropriate for the intended audience. Ask yourself:

- Has the purpose of the book been achieved?

- What contributions does the book make to the field?

- Is the treatment of the subject matter objective or at least balanced in describing all sides of a debate?

- Are there facts and evidence that have been omitted?

- What kinds of data, if any, are used to support the author's thesis statement?

- Can the same data be interpreted to explain alternate outcomes?

- Is the writing style clear and effective?

- Does the book raise important or provocative issues or topics for discussion?

- Does the book bring attention to the need for further research?

- What has been left out?

Support your evaluation with evidence from the text and, when possible, state the book's quality in relation to other scholarly sources. If relevant, note of the book's format, such as, layout, binding, typography, etc. Are there tables, charts, maps, illustrations, text boxes, photographs, or other non-textual elements? Do they aid in understanding the text? Describing this is particularly important in books that contain a lot of non-textual elements.

NOTE: It is important to carefully distinguish your views from those of the author so as not to confuse your reader. Be clear when you are describing an author's point of view versus expressing your own.

V. Examine the Front Matter and Back Matter

Front matter refers to any content before the first chapter of the book. Back matter refers to any information included after the final chapter of the book . Front matter is most often numbered separately from the rest of the text in lower case Roman numerals [i.e. i - xi ]. Critical commentary about front or back matter is generally only necessary if you believe there is something that diminishes the overall quality of the work [e.g., the indexing is poor] or there is something that is particularly helpful in understanding the book's contents [e.g., foreword places the book in an important context].

Front matter that may be considered for evaluation when reviewing its overall quality:

- Table of contents -- is it clear? Is it detailed or general? Does it reflect the true contents of the book? Does it help in understanding a logical sequence of content?

- Author biography -- also found as back matter, the biography of author(s) can be useful in determining the authority of the writer and whether the book builds on prior research or represents new research. In scholarly reviews, noting the author's affiliation and prior publications can be a factor in helping the reader determine the overall validity of the work [i.e., are they associated with a research center devoted to studying the problem under investigation].

- Foreword -- the purpose of a foreword is to introduce the reader to the author and the content of the book, and to help establish credibility for both. A foreword may not contribute any additional information about the book's subject matter, but rather, serves as a means of validating the book's existence. In these cases, the foreword is often written by a leading scholar or expert who endorses the book's contributions to advancing research about the topic. Later editions of a book sometimes have a new foreword prepended [appearing before an older foreword, if there was one], which may be included to explain how the latest edition differs from previous editions. These are most often written by the author.

- Acknowledgements -- scholarly studies in the social sciences often take many years to write, so authors frequently acknowledge the help and support of others in getting their research published. This can be as innocuous as acknowledging the author's family or the publisher. However, an author may acknowledge prominent scholars or subject experts, staff at key research centers, people who curate important archival collections, or organizations that funded the research. In these particular cases, it may be worth noting these sources of support in your review, particularly if the funding organization is biased or its mission is to promote a particular agenda.

- Preface -- generally describes the genesis, purpose, limitations, and scope of the book and may include acknowledgments of indebtedness to people who have helped the author complete the study. Is the preface helpful in understanding the study? Does it provide an effective framework for understanding what's to follow?

- Chronology -- also may be found as back matter, a chronology is generally included to highlight key events related to the subject of the book. Do the entries contribute to the overall work? Is it detailed or very general?

- List of non-textual elements -- a book that contains numerous charts, photographs, maps, tables, etc. will often list these items after the table of contents in the order that they appear in the text. Is this useful?

Back matter that may be considered for evaluation when reviewing its overall quality:

- Afterword -- this is a short, reflective piece written by the author that takes the form of a concluding section, final commentary, or closing statement. It is worth mentioning in a review if it contributes information about the purpose of the book, gives a call to action, summarizes key recommendations or next steps, or asks the reader to consider key points made in the book.

- Appendix -- is the supplementary material in the appendix or appendices well organized? Do they relate to the contents or appear superfluous? Does it contain any essential information that would have been more appropriately integrated into the text?

- Index -- are there separate indexes for names and subjects or one integrated index. Is the indexing thorough and accurate? Are elements used, such as, bold or italic fonts to help identify specific places in the book? Does the index include "see also" references to direct you to related topics?

- Glossary of Terms -- are the definitions clearly written? Is the glossary comprehensive or are there key terms missing? Are any terms or concepts mentioned in the text not included that should have been?

- Endnotes -- examine any endnotes as you read from chapter to chapter. Do they provide important additional information? Do they clarify or extend points made in the body of the text? Should any notes have been better integrated into the text rather than separated? Do the same if the author uses footnotes.

- Bibliography/References/Further Readings -- review any bibliography, list of references to sources, and/or further readings the author may have included. What kinds of sources appear [e.g., primary or secondary, recent or old, scholarly or popular, etc.]? How does the author make use of them? Be sure to note important omissions of sources that you believe should have been utilized, including important digital resources or archival collections.

VI. Summarize and Comment

State your general conclusions briefly and succinctly. Pay particular attention to the author's concluding chapter and/or afterword. Is the summary convincing? List the principal topics, and briefly summarize the author’s ideas about these topics, main points, and conclusions. If appropriate and to help clarify your overall evaluation, use specific references to text and quotations to support your statements. If your thesis has been well argued, the conclusion should follow naturally. It can include a final assessment or simply restate your thesis. Do not introduce new information in the conclusion. If you've compared the book to any other works or used other sources in writing the review, be sure to cite them at the end of your book review in the same writing style as your bibliographic heading of the book.

Book Reviews. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Book Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Gastel, Barbara. "Special Books Section: A Strategy for Reviewing Books for Journals." BioScience 41 (October 1991): 635-637; Hartley, James. "Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (July 2006): 1194–1207; Lee, Alexander D., Bart N. Green, Claire D. Johnson, and Julie Nyquist. "How to Write a Scholarly Book Review for Publication in a Peer-reviewed Journal: A Review of the Literature." Journal of Chiropractic Education 24 (2010): 57-69; Nicolaisen, Jeppe. "The Scholarliness of Published Peer Reviews: A Bibliometric Study of Book Reviews in Selected Social Science Fields." Research Evaluation 11 (2002): 129-140;.Procter, Margaret. The Book Review or Article Critique. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Reading a Book to Review It. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Scarnecchia, David L. "Writing Book Reviews for the Journal Of Range Management and Rangelands." Rangeland Ecology and Management 57 (2004): 418-421; Simon, Linda. "The Pleasures of Book Reviewing." Journal of Scholarly Publishing 27 (1996): 240-241; Writing a Book Review. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Book Reviews. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University.

Writing Tip

Always Read the Foreword and/or the Preface

If they are included in the front matter, a good place for understanding a book's overall purpose, organization, contributions to further understanding of the research problem, and relationship to other studies is to read the preface and the foreword. The foreword may be written by someone other than the author or editor and can be a person who is famous or who has name recognition within the discipline. A foreword is often included to add credibility to the work.

The preface is usually an introductory essay written by the author or editor. It is intended to describe the book's overall purpose, arrangement, scope, and overall contributions to the literature. When reviewing the book, it can be useful to critically evaluate whether the goals set forth in the foreword and/or preface were actually achieved. At the very least, they can establish a foundation for understanding a study's scope and purpose as well as its significance in contributing new knowledge.

Distinguishing between a Foreword, a Preface, and an Introduction . Book Creation Learning Center. Greenleaf Book Group, 2019.

Locating Book Reviews