How to Write an Article Analysis

What Are the Five Parts of an Argumentative Essay?

As you write an article analysis, focus on writing a summary of the main points followed by an analytical critique of the author’s purpose.

Knowing how to write an article analysis paper involves formatting, critical thinking of the literature, a purpose of the article and evaluation of the author’s point of view. In an article analysis critique, you integrate your perspective of the author about a specific topic into a mix of reasoning and arguments. So, you develop an argumentative approach to the point of view of the author. However, a careful distinction occurs between summary and analysis.

When presenting your findings of the article analysis, you might want to summarize the main points, which allows you to formulate a thesis statement. Then, inform the readers about the analytical aspects the author presents in his arguments. Most likely, developing ideas on how to write an article analysis entails a meticulous approach to the critical thinking of the author.

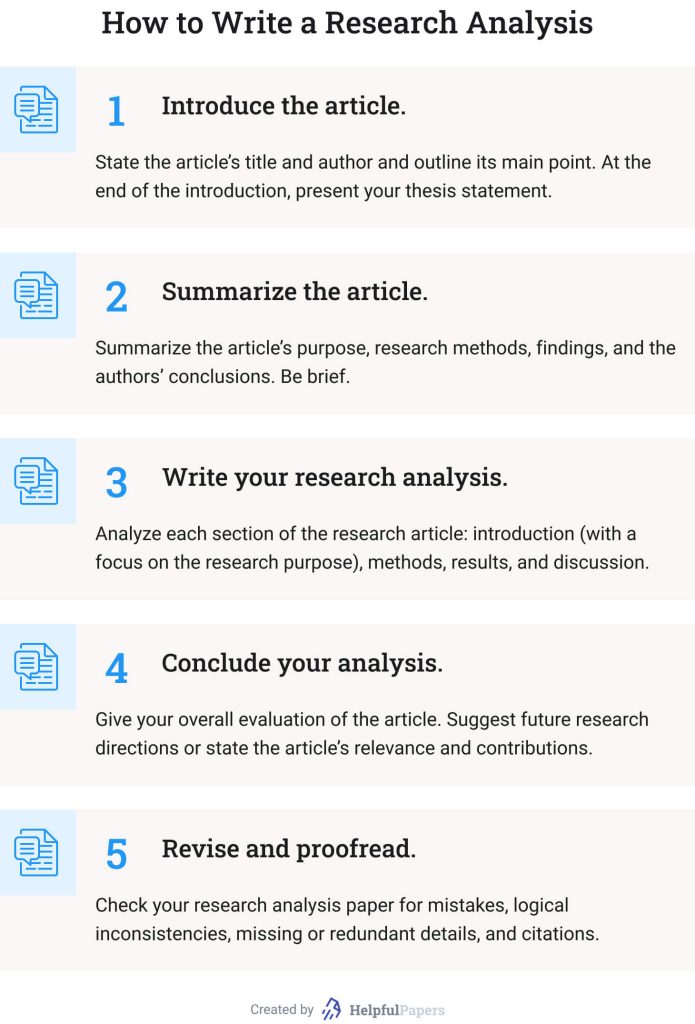

Writing Steps for an Article Analysis

As with any formal paper, you want to begin by quickly reading the article to get the main points. Once you generate a general idea of the point of view of the author, start analyzing the main ideas of each paragraph. An ideal way to take notes based on the reading is to jot them down in the margin of the article. If that's not possible, include notes on your computer or a separate piece of paper. Interact with the text you're reading.

Becoming an active reader helps you decide the relevant information the author intends to communicate. At this point, you might want to include a summary of the main ideas. After you finish writing down the main points, read them to yourself and decide on a concise thesis statement. To do so, begin with the author’s name followed by the title of the article. Next, complete the sentence with your analytical perspective.

Ideally, you want to use outlines, notes and concept mapping to draft your copy. As you progress through the body of the critical part of the paper, include relevant information such as literature references and the author’s purpose for the article. Formal documents, such as an article analysis, also use in-text citation and proofreading. Any academic paper includes a grammar, spelling and mechanics proofreading. Make sure you double-check your paper before submission.

When you write the summary of the article, focus on the purpose of the paper and develop ideas that inform the reader in an unbiased manner. One of the most crucial parts of an analysis essay is the citation of the author and the title of the article. First, introduce the author by first and last name followed by the title of the article. Add variety to your sentence structure by using different formats. For example, you can use “Title,” author’s name, then a brief explanation of the purpose of the piece. Also, many sentences might begin with the author, “Title,” then followed by a description of the main points. By implementing active, explicit verbs into your sentences, you'll show a clear understanding of the material.

Much like any formal paper, consider the most substantial points as your main ideas followed by evidence and facts from the author’s persuasive text. Remember to use transition words to guide your readers in the writing. Those transition phrases or words encourage readers to understand your perspective of the author’s purpose in the article. More importantly, as you write the body of the analysis essay, use the author’s name and article title at the beginning of a paragraph.

When you write your evidence-based arguments, keep the author’s last name throughout the paper. Besides writing your critique of the author’s purpose, remember the audience. The readers relate to your perspective based on what you write. So, use facts and evidence when making inferences about the author’s point of view.

Description of an Article Analysis Essay

When you analyze an article based on the argumentative evidence, generate ideas that support or not the author’s point of view. Although the author’s purpose to communicate the intentions of the article may be clear, you need to evaluate the reasons for writing the piece. Since the basis of your analysis consists of argumentative evidence, elaborate a concise and clear thesis. However, don't rely on the thesis to stay the same as you research the article.

At many times, you'll find that you'll change your argument when you see new facts. In this way, you might want to use text, reader, author, context and exigence approaches. You don't need elaborate ideas. Just use the author’s text so that the reader understands the point of views. However, evaluate the strong tone of the author and the validity of the claims in the article. So, use the context of the article.

Then, ask yourself if the author explains the purpose of his or her persuasive reasons. As you discern the facts and evidence of the article, analyze the point of views carefully. Look for assumptions without basis and biased ideas that aren't valid. An analysis example paragraph easily includes your perspective of the author’s purpose and whether you agree or not. Don't be surprised if your critique changes as you research other authors about the article.

Consequently, your response might end up agreeing, disagreeing or being somewhat in between despite your efforts of finding supporting evidence. Regardless of the consequences of your research of the literature and the perspective of the author’s point of view, maintain a definite purpose in writing. Don't fluctuate from agreement and disagreement. Focusing your analysis on presenting the points of view of the author so readers understand it and disseminating that critique is the basis of your paper.

When reading the text carefully, analyze the main points and explain the reasons of the author. Also, as you describe the document, offer evidence and facts to eliminate any biases. In an argumentative analysis, the focus of the writer can quickly shift. Avoid ineffective ways of approaching the author’s point of view that make the writing vague and lack supporting evidence. A clear way to stay away from biases is to use quotes from the author. However, using excessive amounts of quotes is counterproductive. Use author quotes sparingly.

As you develop your own ideas about the author’s viewpoints, use deductive reasoning to analyze the various aspects of the article. Often, you'll find the historical background influenced the author or persuaded the author to challenge the ideals of the time. Distinguishing between writing a summary and an analysis paper is crucial to your essay. You might find that using a review at the beginning of your article indicates a clear perspective to your analysis. Hence, a summary explains the main points of a paper in a concise manner.

You condense the original text, describe the main points, write your thesis and form no opinion about the article. On the other hand, an analysis is the breakdown of the author’s arguments that you use to derive the purpose of the author. When analyzing an article, you're dissecting the main points to draw conclusions about the persuasive ideas of the author. Furthermore, you offer argumentative evidence, strengths and weaknesses of the main points. More importantly, you don't give your opinion. Rather than providing comments on the author’s point of views, you compile evidence of how the author persuades readers to think about a particular topic and whether the author elaborates it adequately.

Examples of an Article Analysis

A summary and analysis essay example illustrates the arguments the author makes and how those claims are valid. For instance, a sample article analysis of “Sex, Lies, and Conversation; Why Is It So Hard for Men and Women to Talk to Each Other” by Deborah Tannen begins with a summary of the main critical points followed by an analytical perspective. One of the precise ways to summarize is to focus on the main ideas that Tannen uses to distinguish between men and women.

The writer of the summary also clearly states how one idea correlates to the other without presenting biases or opinions. Also, the writer doesn't take any sides on whether men or women are to blame for miscommunication. Instead, the summary points to the communication differences between men and women. In the analytical section of the sample, the writer immediately takes a transparent approach to the article and the author. The analysis shows apparent examples from the article with quotes and refers back to the article connecting miscommunication with misinterpretation. Finally, the writer poses various questions that Tannen didn't address, such as strategies for effective communication. However, the writer gives the reader the purpose of Tannen’s article and the reasons the author wrote it.

Another example of an article analysis is “The Year That Changed Everything” by Lance Morrow. The writer presents a concise summary of the elected government positions of Nixon, Kennedy and Johnson. Furthermore, the writer distinguishes between the three elected men's positions and discusses the similarities. The summary tends to lean toward a more powerful tone but effectively explains the author’s point of view for each one of these men. Then, the writer further describes the ideals of the period between morality and immoral values. The analytical aspect of the sample shows the reader the author’s powerful message.

The writer immediately lets the reader know about the persuasive nature of the article and the relevance of the time. For instance, the writer shows the reader in various parts of the article by suggesting examples in specific paragraph numbers. The writer also makes a powerful impact with the use of quotes embedded into the text. The writer uses transition words and active verbs, such as more examples, links, uncovering and secrets, and backs this claim up to describe Morrow’s purpose for the article. The analysis has the audience in mind.

The writer points out the specific details of the time era that only people of the time would relate. More importantly, the writer analyzes Morrow’s ideas as critical to formulating an opinion about Nixon, Kennedy and Johnson. However, the writer points out the assumptions Morrow makes between personal lifestyle and how it affects the political arena. Moreover, the writer suggests that Morrow’s claims aren't entirely valid just because the author mentions historical events. Unlike Tannen’s analytical example, the writer lets the readers know the misconnection between moral value and the lifestyle of many people at the time.

Both article analyses show a clear way to present different persuasive points of view. Unlike a summary, an analysis approach offers the reader an explicit representation of the author’s viewpoints without any opinions. The writers of each sample focus on providing evidence, facts and reasonable statements. Consequently, each example demonstrates the proper use of the critical analysis of the literature and evaluates the purpose of the author. Without seeking an agreement or not, the writer clearly distinguishes between a summary and an analysis of each article.

Related Articles

What Are Two Types of Research Papers?

How to Set Up a Rhetorical Analysis

How to Write a Thesis & Introduction for a Critical Reflection Essay

The Parts of an Argument

How to Write a Technical Essay

How to Write a Critical Summary of an Article

How to Analyze Expository Writing

How to Do a Summary for a Research Paper

- Owlcation: How to Write a Summary, Analysis, and Response Essay Paper with Examples

- Education: One How To: How to Write a Text Analysis Essay

Barbara earned a B. S. in Biochemistry and Chemistry from the Univ. of Houston and the Univ. of Central Florida, respectively. Besides working as a chemist for the pharmaceutical and water industry, she pursued her degree in secondary science teaching. Barbara now writes and researches educational content for blogs and higher-ed sites.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Journal article analysis assignments require you to summarize and critically assess the quality of an empirical research study published in a scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer-reviewed] journal. The article may be assigned by the professor, chosen from course readings listed in the syllabus, or you must locate an article on your own, usually with the requirement that you search using a reputable library database, such as, JSTOR or ProQuest . The article chosen is expected to relate to the overall discipline of the course, specific course content, or key concepts discussed in class. In some cases, the purpose of the assignment is to analyze an article that is part of the literature review for a future research project.

Analysis of an article can be assigned to students individually or as part of a small group project. The final product is usually in the form of a short paper [typically 1- 6 double-spaced pages] that addresses key questions the professor uses to guide your analysis or that assesses specific parts of a scholarly research study [e.g., the research problem, methodology, discussion, conclusions or findings]. The analysis paper may be shared on a digital course management platform and/or presented to the class for the purpose of promoting a wider discussion about the topic of the study. Although assigned in any level of undergraduate and graduate coursework in the social and behavioral sciences, professors frequently include this assignment in upper division courses to help students learn how to effectively identify, read, and analyze empirical research within their major.

Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Benefits of Journal Article Analysis Assignments

Analyzing and synthesizing a scholarly journal article is intended to help students obtain the reading and critical thinking skills needed to develop and write their own research papers. This assignment also supports workplace skills where you could be asked to summarize a report or other type of document and report it, for example, during a staff meeting or for a presentation.

There are two broadly defined ways that analyzing a scholarly journal article supports student learning:

Improve Reading Skills

Conducting research requires an ability to review, evaluate, and synthesize prior research studies. Reading prior research requires an understanding of the academic writing style , the type of epistemological beliefs or practices underpinning the research design, and the specific vocabulary and technical terminology [i.e., jargon] used within a discipline. Reading scholarly articles is important because academic writing is unfamiliar to most students; they have had limited exposure to using peer-reviewed journal articles prior to entering college or students have yet to gain exposure to the specific academic writing style of their disciplinary major. Learning how to read scholarly articles also requires careful and deliberate concentration on how authors use specific language and phrasing to convey their research, the problem it addresses, its relationship to prior research, its significance, its limitations, and how authors connect methods of data gathering to the results so as to develop recommended solutions derived from the overall research process.

Improve Comprehension Skills

In addition to knowing how to read scholarly journals articles, students must learn how to effectively interpret what the scholar(s) are trying to convey. Academic writing can be dense, multi-layered, and non-linear in how information is presented. In addition, scholarly articles contain footnotes or endnotes, references to sources, multiple appendices, and, in some cases, non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts] that can break-up the reader’s experience with the narrative flow of the study. Analyzing articles helps students practice comprehending these elements of writing, critiquing the arguments being made, reflecting upon the significance of the research, and how it relates to building new knowledge and understanding or applying new approaches to practice. Comprehending scholarly writing also involves thinking critically about where you fit within the overall dialogue among scholars concerning the research problem, finding possible gaps in the research that require further analysis, or identifying where the author(s) has failed to examine fully any specific elements of the study.

In addition, journal article analysis assignments are used by professors to strengthen discipline-specific information literacy skills, either alone or in relation to other tasks, such as, giving a class presentation or participating in a group project. These benefits can include the ability to:

- Effectively paraphrase text, which leads to a more thorough understanding of the overall study;

- Identify and describe strengths and weaknesses of the study and their implications;

- Relate the article to other course readings and in relation to particular research concepts or ideas discussed during class;

- Think critically about the research and summarize complex ideas contained within;

- Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

- Model the type of source summary and critique you should do for any college-level research paper; and,

- Increase interest and engagement with the research problem of the study as well as with the discipline.

Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946.

Structure and Organization

A journal article analysis paper should be written in paragraph format and include an instruction to the study, your analysis of the research, and a conclusion that provides an overall assessment of the author's work, along with an explanation of what you believe is the study's overall impact and significance. Unless the purpose of the assignment is to examine foundational studies published many years ago, you should select articles that have been published relatively recently [e.g., within the past few years].

Since the research has been completed, reference to the study in your paper should be written in the past tense, with your analysis stated in the present tense [e.g., “The author portrayed access to health care services in rural areas as primarily a problem of having reliable transportation. However, I believe the author is overgeneralizing this issue because...”].

Introduction Section

The first section of a journal analysis paper should describe the topic of the article and highlight the author’s main points. This includes describing the research problem and theoretical framework, the rationale for the research, the methods of data gathering and analysis, the key findings, and the author’s final conclusions and recommendations. The narrative should focus on the act of describing rather than analyzing. Think of the introduction as a more comprehensive and detailed descriptive abstract of the study.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the introduction section may include:

- Who are the authors and what credentials do they hold that contributes to the validity of the study?

- What was the research problem being investigated?

- What type of research design was used to investigate the research problem?

- What theoretical idea(s) and/or research questions were used to address the problem?

- What was the source of the data or information used as evidence for analysis?

- What methods were applied to investigate this evidence?

- What were the author's overall conclusions and key findings?

Critical Analysis Section

The second section of a journal analysis paper should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the study and analyze its significance and impact. This section is where you shift the narrative from describing to analyzing. Think critically about the research in relation to other course readings, what has been discussed in class, or based on your own life experiences. If you are struggling to identify any weaknesses, explain why you believe this to be true. However, no study is perfect, regardless of how laudable its design may be. Given this, think about the repercussions of the choices made by the author(s) and how you might have conducted the study differently. Examples can include contemplating the choice of what sources were included or excluded in support of examining the research problem, the choice of the method used to analyze the data, or the choice to highlight specific recommended courses of action and/or implications for practice over others. Another strategy is to place yourself within the research study itself by thinking reflectively about what may be missing if you had been a participant in the study or if the recommended courses of action specifically targeted you or your community.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the analysis section may include:

Introduction

- Did the author clearly state the problem being investigated?

- What was your reaction to and perspective on the research problem?

- Was the study’s objective clearly stated? Did the author clearly explain why the study was necessary?

- How well did the introduction frame the scope of the study?

- Did the introduction conclude with a clear purpose statement?

Literature Review

- Did the literature review lay a foundation for understanding the significance of the research problem?

- Did the literature review provide enough background information to understand the problem in relation to relevant contexts [e.g., historical, economic, social, cultural, etc.].

- Did literature review effectively place the study within the domain of prior research? Is anything missing?

- Was the literature review organized by conceptual categories or did the author simply list and describe sources?

- Did the author accurately explain how the data or information were collected?

- Was the data used sufficient in supporting the study of the research problem?

- Was there another methodological approach that could have been more illuminating?

- Give your overall evaluation of the methods used in this article. How much trust would you put in generating relevant findings?

Results and Discussion

- Were the results clearly presented?

- Did you feel that the results support the theoretical and interpretive claims of the author? Why?

- What did the author(s) do especially well in describing or analyzing their results?

- Was the author's evaluation of the findings clearly stated?

- How well did the discussion of the results relate to what is already known about the research problem?

- Was the discussion of the results free of repetition and redundancies?

- What interpretations did the authors make that you think are in incomplete, unwarranted, or overstated?

- Did the conclusion effectively capture the main points of study?

- Did the conclusion address the research questions posed? Do they seem reasonable?

- Were the author’s conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented?

- Has the author explained how the research added new knowledge or understanding?

Overall Writing Style

- If the article included tables, figures, or other non-textual elements, did they contribute to understanding the study?

- Were ideas developed and related in a logical sequence?

- Were transitions between sections of the article smooth and easy to follow?

Overall Evaluation Section

The final section of a journal analysis paper should bring your thoughts together into a coherent assessment of the value of the research study . This section is where the narrative flow transitions from analyzing specific elements of the article to critically evaluating the overall study. Explain what you view as the significance of the research in relation to the overall course content and any relevant discussions that occurred during class. Think about how the article contributes to understanding the overall research problem, how it fits within existing literature on the topic, how it relates to the course, and what it means to you as a student researcher. In some cases, your professor will also ask you to describe your experiences writing the journal article analysis paper as part of a reflective learning exercise.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the conclusion and evaluation section may include:

- Was the structure of the article clear and well organized?

- Was the topic of current or enduring interest to you?

- What were the main weaknesses of the article? [this does not refer to limitations stated by the author, but what you believe are potential flaws]

- Was any of the information in the article unclear or ambiguous?

- What did you learn from the research? If nothing stood out to you, explain why.

- Assess the originality of the research. Did you believe it contributed new understanding of the research problem?

- Were you persuaded by the author’s arguments?

- If the author made any final recommendations, will they be impactful if applied to practice?

- In what ways could future research build off of this study?

- What implications does the study have for daily life?

- Was the use of non-textual elements, footnotes or endnotes, and/or appendices helpful in understanding the research?

- What lingering questions do you have after analyzing the article?

NOTE: Avoid using quotes. One of the main purposes of writing an article analysis paper is to learn how to effectively paraphrase and use your own words to summarize a scholarly research study and to explain what the research means to you. Using and citing a direct quote from the article should only be done to help emphasize a key point or to underscore an important concept or idea.

Business: The Article Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing, Grand Valley State University; Bachiochi, Peter et al. "Using Empirical Article Analysis to Assess Research Methods Courses." Teaching of Psychology 38 (2011): 5-9; Brosowsky, Nicholaus P. et al. “Teaching Undergraduate Students to Read Empirical Articles: An Evaluation and Revision of the QALMRI Method.” PsyArXi Preprints , 2020; Holster, Kristin. “Article Evaluation Assignment”. TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology . Washington DC: American Sociological Association, 2016; Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reviewer's Guide . SAGE Reviewer Gateway, SAGE Journals; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Gyuris, Emma, and Laura Castell. "To Tell Them or Show Them? How to Improve Science Students’ Skills of Critical Reading." International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 21 (2013): 70-80; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students Make the Most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Writing Tip

Not All Scholarly Journal Articles Can Be Critically Analyzed

There are a variety of articles published in scholarly journals that do not fit within the guidelines of an article analysis assignment. This is because the work cannot be empirically examined or it does not generate new knowledge in a way which can be critically analyzed.

If you are required to locate a research study on your own, avoid selecting these types of journal articles:

- Theoretical essays which discuss concepts, assumptions, and propositions, but report no empirical research;

- Statistical or methodological papers that may analyze data, but the bulk of the work is devoted to refining a new measurement, statistical technique, or modeling procedure;

- Articles that review, analyze, critique, and synthesize prior research, but do not report any original research;

- Brief essays devoted to research methods and findings;

- Articles written by scholars in popular magazines or industry trade journals;

- Pre-print articles that have been posted online, but may undergo further editing and revision by the journal's editorial staff before final publication; and

- Academic commentary that discusses research trends or emerging concepts and ideas, but does not contain citations to sources.

Journal Analysis Assignment - Myers . Writing@CSU, Colorado State University; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Giving an Oral Presentation >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

- Business Skills

- Business Writing

How to Write an Analysis

Last Updated: April 3, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Megaera Lorenz, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 289,427 times.

An analysis is a piece of writing that looks at some aspect of a document in detail. To write a good analysis, you’ll need to ask yourself questions that focus on how and why the document works the way it does. You can start the process by gathering information about the subject of your analysis and defining the questions your analysis will answer. Once you’ve outlined your main arguments, look for specific evidence to support them. You can then work on putting your analysis together into a coherent piece of writing.

Gathering Information and Building Your Argument

- If your analysis is supposed to answer a specific question or focus on a particular aspect of the document you are analyzing.

- If there are any length or formatting requirements for the analysis.

- The citation style your instructor wants you to use.

- On what criteria your instructor will evaluate your analysis (e.g., organization, originality, good use of references and quotations, or correct spelling and grammar).

- The title of the document (if it has one).

- The name of the creator of the document. For example, depending on the type of document you’re working with, this could be the author, artist, director, performer, or photographer.

- The form and medium of the document (e.g., “Painting, oil on canvas”).

- When and where the document was created.

- The historical and cultural context of the work.

- Who you believe the intended audience is for the advertisement.

- What rhetorical choices the author made to persuade the audience of their main point.

- What product is being advertised.

- How the poster uses images to make the product look appealing.

- Whether there is any text in the poster, and, if so, how it works together with the images to reinforce the message of the ad.

- What the purpose of the ad is or what its main point is.

- For example, if you’re analyzing an advertisement poster, you might focus on the question: “How does this poster use colors to symbolize the problem that the product is intended to fix? Does it also use color to represent the beneficial results of using the product?”

- For example, you might write, “This poster uses the color red to symbolize the pain of a headache. The blue elements in the design represent the relief brought by the product.”

- You could develop the argument further by saying, “The colors used in the text reinforce the use of colors in the graphic elements of the poster, helping the viewer make a direct connection between the words and images.”

- For example, if you’re arguing that the advertisement poster uses red to represent pain, you might point out that the figure of the headache sufferer is red, while everyone around them is blue. Another piece of evidence might be the use of red lettering for the words “HEADACHE” and “PAIN” in the text of the poster.

- You could also draw on outside evidence to support your claims. For example, you might point out that in the country where the advertisement was produced, the color red is often symbolically associated with warnings or danger.

Tip: If you’re analyzing a text, make sure to properly cite any quotations that you use to support your arguments. Put any direct quotations in quotation marks (“”) and be sure to give location information, such as the page number where the quote appears. Additionally, follow the citation requirements for the style guide assigned by your instructor or one that's commonly used for the subject matter you're writing about.

Organizing and Drafting Your Analysis

- For example, “The poster ‘Say! What a relief,’ created in 1932 by designer Dorothy Plotzky, uses contrasting colors to symbolize the pain of a headache and the relief brought by Miss Burnham’s Pep-Em-Up Pills. The red elements denote pain, while blue ones indicate soothing relief.”

Tip: Your instructor might have specific directions about which information to include in your thesis statement (e.g., the title, author, and date of the document you are analyzing). If you’re not sure how to format your thesis statement or topic sentence, don’t hesitate to ask.

- a. Background

- ii. Analysis/Explanation

- iii. Example

- iv. Analysis/Explanation

- III. Conclusion

- For example, “In the late 1920s, Kansas City schoolteacher Ethel Burnham developed a patent headache medication that quickly achieved commercial success throughout the American Midwest. The popularity of the medicine was largely due to a series of simple but eye-catching advertising posters that were created over the next decade. The poster ‘Say! What a relief,’ created in 1932 by designer Dorothy Plotzky, uses contrasting colors to symbolize the pain of a headache and the relief brought by Miss Burnham’s Pep-Em-Up Pills.”

- Make sure to include clear transitions between each argument and each paragraph. Use transitional words and phrases, such as “Furthermore,” “Additionally,” “For example,” “Likewise,” or “In contrast . . .”

- The best way to organize your arguments will vary based on the individual topic and the specific points you are trying to make. For example, in your analysis of the poster, you might start with arguments about the red visual elements and then move on to a discussion about how the red text fits in.

- For example, you might end your essay with a few sentences about how other advertisements at the time might have been influenced by Dorothy Plotzky’s use of colors.

- For example, in your discussion of the advertisement, avoid stating that you think the art is “beautiful” or that the advertisement is “boring.” Instead, focus on what the poster was supposed to accomplish and how the designer attempted to achieve those goals.

Polishing Your Analysis

- For example, if your essay currently skips around between discussions of the red and blue elements of the poster, consider reorganizing it so that you discuss all the red elements first, then focus on the blue ones.

- For example, you might look for places where you could provide additional examples to support one of your major arguments.

- For example, if you included a paragraph about Dorothy Plotzky’s previous work as a children’s book illustrator, you may want to cut it if it doesn’t somehow relate to her use of color in advertising.

- Cutting material out of your analysis may be difficult, especially if you put a lot of thought into each sentence or found the additional material really interesting. Your analysis will be stronger if you keep it concise and to the point, however.

- You may find it helpful to have someone else go over your essay and look for any mistakes you might have missed.

Tip: When you’re reading silently, it’s easy to miss typos and other small errors because your brain corrects them automatically. Reading your work out loud can make problems easier to spot.

Sample Analysis Outline and Conclusion

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-do-i-make-sure-i-understand-an-assignment-.html

- ↑ https://www.bucks.edu/media/bcccmedialibrary/pdf/HOWTOWRITEALITERARYANALYSISESSAY_10.15.07_001.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/visual_rhetoric/analyzing_visual_documents/elements_of_analysis.html

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-can-i-create-stronger-analysis-.html

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-do-i-decide-what-i-should-argue-.html

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-do-i-effectively-integrate-textual-evidence-.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uagc.edu/writing-a-thesis

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/visual_rhetoric/analyzing_visual_documents/organizing_your_analysis.html

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-do-i-write-an-intro--conclusion----body-paragraph.html

- ↑ http://utminers.utep.edu/omwilliamson/engl0310/Textanalysis.htm

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/graduate_writing/graduate_writing_topics/graduate_writing_organization_structure_new.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/mechanics/sentence_clarity.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/conciseness-handout/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you need to write an analysis, first look closely at your assignment to make sure you understand the requirements. Then, gather background information about the document you’ll be analyzing and do a close read so that you’re thoroughly familiar with the subject matter. If it’s not already specified in your assignment, come up with one or more specific question’s you’d like your analysis to answer, then outline your main arguments. Finally, gather evidence and examples to support your arguments. Read on to learn how to organize, draft, and polish your analysis! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Critical Analysis

Definition:

Critical analysis is a process of examining a piece of work or an idea in a systematic, objective, and analytical way. It involves breaking down complex ideas, concepts, or arguments into smaller, more manageable parts to understand them better.

Types of Critical Analysis

Types of Critical Analysis are as follows:

Literary Analysis

This type of analysis focuses on analyzing and interpreting works of literature , such as novels, poetry, plays, etc. The analysis involves examining the literary devices used in the work, such as symbolism, imagery, and metaphor, and how they contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

Film Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting films, including their themes, cinematography, editing, and sound. Film analysis can also include evaluating the director’s style and how it contributes to the overall message of the film.

Art Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting works of art , such as paintings, sculptures, and installations. The analysis involves examining the elements of the artwork, such as color, composition, and technique, and how they contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

Cultural Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting cultural artifacts , such as advertisements, popular music, and social media posts. The analysis involves examining the cultural context of the artifact and how it reflects and shapes cultural values, beliefs, and norms.

Historical Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting historical documents , such as diaries, letters, and government records. The analysis involves examining the historical context of the document and how it reflects the social, political, and cultural attitudes of the time.

Philosophical Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting philosophical texts and ideas, such as the works of philosophers and their arguments. The analysis involves evaluating the logical consistency of the arguments and assessing the validity and soundness of the conclusions.

Scientific Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting scientific research studies and their findings. The analysis involves evaluating the methods used in the study, the data collected, and the conclusions drawn, and assessing their reliability and validity.

Critical Discourse Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting language use in social and political contexts. The analysis involves evaluating the power dynamics and social relationships conveyed through language use and how they shape discourse and social reality.

Comparative Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting multiple texts or works of art and comparing them to each other. The analysis involves evaluating the similarities and differences between the texts and how they contribute to understanding the themes and meanings conveyed.

Critical Analysis Format

Critical Analysis Format is as follows:

I. Introduction

- Provide a brief overview of the text, object, or event being analyzed

- Explain the purpose of the analysis and its significance

- Provide background information on the context and relevant historical or cultural factors

II. Description

- Provide a detailed description of the text, object, or event being analyzed

- Identify key themes, ideas, and arguments presented

- Describe the author or creator’s style, tone, and use of language or visual elements

III. Analysis

- Analyze the text, object, or event using critical thinking skills

- Identify the main strengths and weaknesses of the argument or presentation

- Evaluate the reliability and validity of the evidence presented

- Assess any assumptions or biases that may be present in the text, object, or event

- Consider the implications of the argument or presentation for different audiences and contexts

IV. Evaluation

- Provide an overall evaluation of the text, object, or event based on the analysis

- Assess the effectiveness of the argument or presentation in achieving its intended purpose

- Identify any limitations or gaps in the argument or presentation

- Consider any alternative viewpoints or interpretations that could be presented

- Summarize the main points of the analysis and evaluation

- Reiterate the significance of the text, object, or event and its relevance to broader issues or debates

- Provide any recommendations for further research or future developments in the field.

VI. Example

- Provide an example or two to support your analysis and evaluation

- Use quotes or specific details from the text, object, or event to support your claims

- Analyze the example(s) using critical thinking skills and explain how they relate to your overall argument

VII. Conclusion

- Reiterate your thesis statement and summarize your main points

- Provide a final evaluation of the text, object, or event based on your analysis

- Offer recommendations for future research or further developments in the field

- End with a thought-provoking statement or question that encourages the reader to think more deeply about the topic

How to Write Critical Analysis

Writing a critical analysis involves evaluating and interpreting a text, such as a book, article, or film, and expressing your opinion about its quality and significance. Here are some steps you can follow to write a critical analysis:

- Read and re-read the text: Before you begin writing, make sure you have a good understanding of the text. Read it several times and take notes on the key points, themes, and arguments.

- Identify the author’s purpose and audience: Consider why the author wrote the text and who the intended audience is. This can help you evaluate whether the author achieved their goals and whether the text is effective in reaching its audience.

- Analyze the structure and style: Look at the organization of the text and the author’s writing style. Consider how these elements contribute to the overall meaning of the text.

- Evaluate the content : Analyze the author’s arguments, evidence, and conclusions. Consider whether they are logical, convincing, and supported by the evidence presented in the text.

- Consider the context: Think about the historical, cultural, and social context in which the text was written. This can help you understand the author’s perspective and the significance of the text.

- Develop your thesis statement : Based on your analysis, develop a clear and concise thesis statement that summarizes your overall evaluation of the text.

- Support your thesis: Use evidence from the text to support your thesis statement. This can include direct quotes, paraphrases, and examples from the text.

- Write the introduction, body, and conclusion : Organize your analysis into an introduction that provides context and presents your thesis, a body that presents your evidence and analysis, and a conclusion that summarizes your main points and restates your thesis.

- Revise and edit: After you have written your analysis, revise and edit it to ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and well-organized. Check for spelling and grammar errors, and make sure that your analysis is logically sound and supported by evidence.

When to Write Critical Analysis

You may want to write a critical analysis in the following situations:

- Academic Assignments: If you are a student, you may be assigned to write a critical analysis as a part of your coursework. This could include analyzing a piece of literature, a historical event, or a scientific paper.

- Journalism and Media: As a journalist or media person, you may need to write a critical analysis of current events, political speeches, or media coverage.

- Personal Interest: If you are interested in a particular topic, you may want to write a critical analysis to gain a deeper understanding of it. For example, you may want to analyze the themes and motifs in a novel or film that you enjoyed.

- Professional Development : Professionals such as writers, scholars, and researchers often write critical analyses to gain insights into their field of study or work.

Critical Analysis Example

An Example of Critical Analysis Could be as follow:

Research Topic:

The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance

Introduction:

The introduction of the research topic is clear and provides an overview of the issue. However, it could benefit from providing more background information on the prevalence of online learning and its potential impact on student performance.

Literature Review:

The literature review is comprehensive and well-structured. It covers a broad range of studies that have examined the relationship between online learning and student performance. However, it could benefit from including more recent studies and providing a more critical analysis of the existing literature.

Research Methods:

The research methods are clearly described and appropriate for the research question. The study uses a quasi-experimental design to compare the performance of students who took an online course with those who took the same course in a traditional classroom setting. However, the study may benefit from using a randomized controlled trial design to reduce potential confounding factors.

The results are presented in a clear and concise manner. The study finds that students who took the online course performed similarly to those who took the traditional course. However, the study only measures performance on one course and may not be generalizable to other courses or contexts.

Discussion :

The discussion section provides a thorough analysis of the study’s findings. The authors acknowledge the limitations of the study and provide suggestions for future research. However, they could benefit from discussing potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between online learning and student performance.

Conclusion :

The conclusion summarizes the main findings of the study and provides some implications for future research and practice. However, it could benefit from providing more specific recommendations for implementing online learning programs in educational settings.

Purpose of Critical Analysis

There are several purposes of critical analysis, including:

- To identify and evaluate arguments : Critical analysis helps to identify the main arguments in a piece of writing or speech and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses. This enables the reader to form their own opinion and make informed decisions.

- To assess evidence : Critical analysis involves examining the evidence presented in a text or speech and evaluating its quality and relevance to the argument. This helps to determine the credibility of the claims being made.

- To recognize biases and assumptions : Critical analysis helps to identify any biases or assumptions that may be present in the argument, and evaluate how these affect the credibility of the argument.

- To develop critical thinking skills: Critical analysis helps to develop the ability to think critically, evaluate information objectively, and make reasoned judgments based on evidence.

- To improve communication skills: Critical analysis involves carefully reading and listening to information, evaluating it, and expressing one’s own opinion in a clear and concise manner. This helps to improve communication skills and the ability to express ideas effectively.

Importance of Critical Analysis

Here are some specific reasons why critical analysis is important:

- Helps to identify biases: Critical analysis helps individuals to recognize their own biases and assumptions, as well as the biases of others. By being aware of biases, individuals can better evaluate the credibility and reliability of information.

- Enhances problem-solving skills : Critical analysis encourages individuals to question assumptions and consider multiple perspectives, which can lead to creative problem-solving and innovation.

- Promotes better decision-making: By carefully evaluating evidence and arguments, critical analysis can help individuals make more informed and effective decisions.

- Facilitates understanding: Critical analysis helps individuals to understand complex issues and ideas by breaking them down into smaller parts and evaluating them separately.

- Fosters intellectual growth : Engaging in critical analysis challenges individuals to think deeply and critically, which can lead to intellectual growth and development.

Advantages of Critical Analysis

Some advantages of critical analysis include:

- Improved decision-making: Critical analysis helps individuals make informed decisions by evaluating all available information and considering various perspectives.

- Enhanced problem-solving skills : Critical analysis requires individuals to identify and analyze the root cause of a problem, which can help develop effective solutions.

- Increased creativity : Critical analysis encourages individuals to think outside the box and consider alternative solutions to problems, which can lead to more creative and innovative ideas.

- Improved communication : Critical analysis helps individuals communicate their ideas and opinions more effectively by providing logical and coherent arguments.

- Reduced bias: Critical analysis requires individuals to evaluate information objectively, which can help reduce personal biases and subjective opinions.

- Better understanding of complex issues : Critical analysis helps individuals to understand complex issues by breaking them down into smaller parts, examining each part and understanding how they fit together.

- Greater self-awareness: Critical analysis helps individuals to recognize their own biases, assumptions, and limitations, which can lead to personal growth and development.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Writing Guide

- Article Writing

How to Analyze an Article

- What is an article analysis

- Outline and structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

- Article analysis format

- Analysis examples

- Article analysis template

What Is an Article Analysis?

- Summarize the main points in the piece – when you get to do an article analysis, you have to analyze the main points so that the reader can understand what the article is all about in general. The summary will be an overview of the story outline, but it is not the main analysis. It just acts to guide the reader to understand what the article is all about in brief.

- Proceed to the main argument and analyze the evidence offered by the writer in the article – this is where analysis begins because you must critique the article by analyzing the evidence given by the piece’s author. You should also point out the flaws in the work and support where it needs to be; it should not necessarily be a positive critique. You are free to pinpoint even the negative part of the story. In other words, you should not rely on one side but be truthful about what you are addressing to the satisfaction of anyone who would read your essay.

- Analyze the piece’s significance – most readers would want to see why you need to make article analysis. It is your role as a writer to emphasize the importance of the article so that the reader can be content with your writing. When your audience gets interested in your work, you will have achieved your aim because the main aim of writing is to convince the reader. The more persuasive you are, the more your article stands out. Focus on motivating your audience, and you will have scored.

Outline and Structure of an Article Analysis

What do you need to write an article analysis, how to write an analysis of an article, step 1: analyze your audience, step 2: read the article.

- The evidence : identify the evidence the writer used in the article to support their claim. While looking into the evidence, you should gauge whether the writer brings out factual evidence or it is personal judgments.

- The argument’s validity: a writer might use many pieces of evidence to support their claims, but you need to identify the sources they use and determine whether they are credible. Credible sources are like scholarly articles and books, and some are not worth relying on for research.

- How convictive are the arguments? You should be able to judge the writer’s persuasion of the audience. An article is usually informative and therefore has to be persuasive to the readers to be considered worthy. If it does not achieve this, you should be able to critique that and illustrate the same.

Step 3: Make the plan

Step 4: write a critical analysis of an article, step 5: edit your essay, article analysis format, article analysis example, what didn’t you know about the article analysis template.

- Read through the piece quickly to get an overview.

- Look for confronting words in the article and note them down.

- Read the piece for the second time while summarizing major points in the literature piece.

- Reflect on the paper’s thesis to affirm and adhere to it in your writing.

- Note the arguments and the evidence used.

- Evaluate the article and focus on your audience.

- Give your opinion and support it to the satisfaction of your audience.

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Forget about ChatGPT and get quality content right away.

How to Critically Analyse an Article

Critical analysis refers to the skill required to evaluate an author’s work. Students are frequently asked to critically analyse a particular journal. The analysis is designed to enhance the reader’s understanding of the thesis and content of the article, and crucially is subjective, because a piece of critical analysis writing is a way for the writer to express their opinions, analysis, and evaluation of the article in question. In essence, the article needs to be broken down into parts, each one analysed separately and then brought together as one piece of critical analysis of the whole.

Key point: you need to be aware that when you are analysing an article your goal is to ensure that your readers understand the main points of the paper with ease. This means demonstrating critical thinking skills, judgement, and evaluation to illustrate how you came to your conclusions and opinions on the work. This might sound simple, and it can be, if you follow our guide to critically analyse an article:

- Before you start your essay, you should read through the paper at least three times.

- The first time ensures you understand, the second allows you to examine the structure of the work and the third enables you to pick out the key points and focus of the thesis statement given by the author (if there is one of course!). During these reads and re-reads you can set down bullet points which will eventually frame your outline and draft for the final work.

- Look for the purpose of the article – is the writer trying to inform through facts and research, are they trying to persuade through logical argument, or are they simply trying to entertain and create an emotional response. Examine your own responses to the article and this will guide to the purpose.

- When you start writing your analysis, avoid phrases such as “I think/believe”, “In my opinion”. The analysis is of the paper, not your views and perspectives.

- Ensure you have clearly indicated the subject of the article so that is evident to the reader.

- Look for both strengths and weaknesses in the work – and always support your assertions with credible, viable sources that are clearly referenced at the end of your work.

- Be open-minded and objective, rely on facts and evidence as you pull your work together.

Structure for Critical Analysis of an Article

Remember, your essay should be in three mains sections: the introduction, the main body, and a conclusion.

Introduction

Your introduction should commence by indicating the title of the work being analysed, including author and date of publication. This should be followed by an indication of the main themes in the thesis statement. Once you have provided the information about the author’s paper, you should then develop your thesis statement which sets out what you intend to achieve or prove with your critical analysis of the article.

Key point: your introduction should be short, succinct and draw your readers in. Keep it simple and concise but interesting enough to encourage further reading.

Overview of the paper

This is an important section to include when writing a critical analysis of an article because it answers the four “w’s”, of what, why, who, when and also the how. This section should include a brief overview of the key ideas in the article, along with the structure, style and dominant point of view expressed. For example,

“The focus of this article is… based on work undertaken… The main thrust of the thesis is that… which is the foundation for an argument which suggests. The conclusion from the authors is that…. However, it can be argued that…

Once you have given the overview and outline, you can then move onto the more detailed analysis.

For each point you make about the article, you should contain this in a separate paragraph. Introduce the point you wish to make, regarding what you see as a strength or weakness of the work, provide evidence for your perspective from reliable and credible sources, and indicate how the authors have achieved, or not their goal in relation to the points made. For each point, you should identify whether the paper is objective, informative, persuasive, and sufficiently unbiased. In addition, identify whether the target audience for the work has been correctly addressed, the survey instruments used are appropriate and the results are presented in a clear and concise way.

If the authors have used tables, figures or graphs do they back up the conclusions made? If not, why not? Again, back up your statements with reliable hard evidence and credible sources, fully referenced at the end of your work.

In the same way that an introduction opens up the analysis to readers, the conclusion should close it. Clearly, concisely and without the addition of any new information not included in the body paragraph.

Key points for a strong conclusion include restating your thesis statement, paraphrased, with a summary of the evidence for the accuracy of your views, combined with identification of how the article could have been improved – in other words, asking the reader to take action.

Key phrases for Critical Analysis of an article

- This article has value because it…

- There is a clear bias within this article based on the focus on…

- It appears that the assumptions made do not correlate with the information presented…

- Aspects of the work suggest that…

- The proposal is therefore that…

- The evidence presented supports the view that…

- The evidence presented however overlooks…

- Whilst the author’s view is generally accurate, it can also be indicated that…

- Closer examination suggests there is an omission in relation to

You may also like

Information Literacy Resource Bank

Reading and critically analysing a journal article.

- Explain the broad categorisations of journal articles

- Explain/outline the peer review process whereby an article is submitted for scholarly evaluation by experts

- Suggest questions you need to ask when reading and critically analysing a journal article

- Provide practical tips to facilitate the effective reading and critical analysis of an article

No comments.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Research Paper Analysis: How to Analyze a Research Article + Example

Why might you need to analyze research? First of all, when you analyze a research article, you begin to understand your assigned reading better. It is also the first step toward learning how to write your own research articles and literature reviews. However, if you have never written a research paper before, it may be difficult for you to analyze one. After all, you may not know what criteria to use to evaluate it. But don’t panic! We will help you figure it out!

In this article, our team has explained how to analyze research papers quickly and effectively. At the end, you will also find a research analysis paper example to see how everything works in practice.

- 🔤 Research Analysis Definition

📊 How to Analyze a Research Article

✍️ how to write a research analysis.

- 📝 Analysis Example

- 🔎 More Examples

🔗 References

🔤 research paper analysis: what is it.

A research paper analysis is an academic writing assignment in which you analyze a scholarly article’s methodology, data, and findings. In essence, “to analyze” means to break something down into components and assess each of them individually and in relation to each other. The goal of an analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. So, when you analyze a research article, you dissect it into elements like data sources , research methods, and results and evaluate how they contribute to the study’s strengths and weaknesses.

📋 Research Analysis Format

A research analysis paper has a pretty straightforward structure. Check it out below!

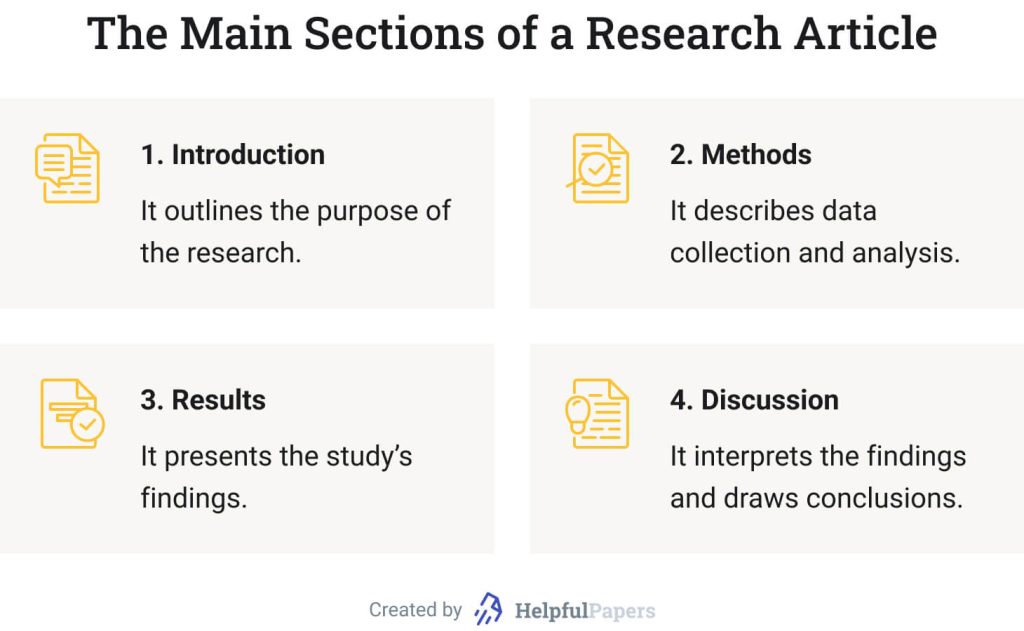

Research articles usually include the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how to analyze a scientific article with a focus on each of its parts.

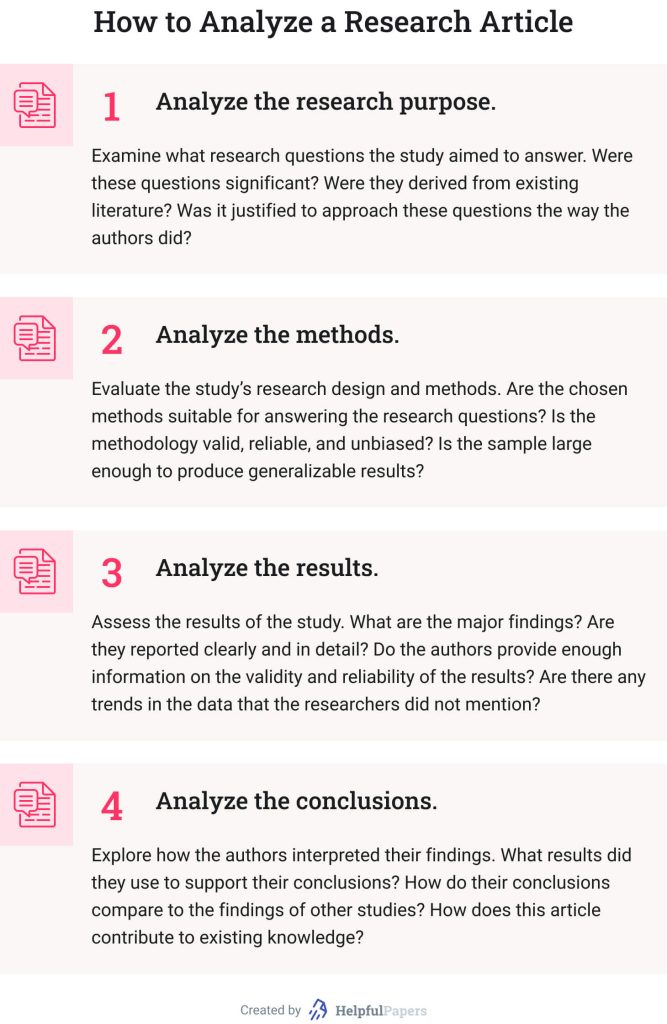

How to Analyze a Research Paper: Purpose

The purpose of the study is usually outlined in the introductory section of the article. Analyzing the research paper’s objectives is critical to establish the context for the rest of your analysis.

When analyzing the research aim, you should evaluate whether it was justified for the researchers to conduct the study. In other words, you should assess whether their research question was significant and whether it arose from existing literature on the topic.

Here are some questions that may help you analyze a research paper’s purpose:

- Why was the research carried out?

- What gaps does it try to fill, or what controversies to settle?

- How does the study contribute to its field?

- Do you agree with the author’s justification for approaching this particular question in this way?

How to Analyze a Paper: Methods

When analyzing the methodology section , you should indicate the study’s research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) and methods used (for example, experiment, case study, correlational research, survey, etc.). After that, you should assess whether these methods suit the research purpose. In other words, do the chosen methods allow scholars to answer their research questions within the scope of their study?

For example, if scholars wanted to study US students’ average satisfaction with their higher education experience, they could conduct a quantitative survey . However, if they wanted to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors influencing US students’ satisfaction with higher education, qualitative interviews would be more appropriate.

When analyzing methods, you should also look at the research sample . Did the scholars use randomization to select study participants? Was the sample big enough for the results to be generalizable to a larger population?

You can also answer the following questions in your methodology analysis:

- Is the methodology valid? In other words, did the researchers use methods that accurately measure the variables of interest?

- Is the research methodology reliable? A research method is reliable if it can produce stable and consistent results under the same circumstances.

- Is the study biased in any way?

- What are the limitations of the chosen methodology?

How to Analyze Research Articles’ Results

You should start the analysis of the article results by carefully reading the tables, figures, and text. Check whether the findings correspond to the initial research purpose. See whether the results answered the author’s research questions or supported the hypotheses stated in the introduction.

To analyze the results section effectively, answer the following questions:

- What are the major findings of the study?

- Did the author present the results clearly and unambiguously?

- Are the findings statistically significant ?

- Does the author provide sufficient information on the validity and reliability of the results?

- Have you noticed any trends or patterns in the data that the author did not mention?

How to Analyze Research: Discussion

Finally, you should analyze the authors’ interpretation of results and its connection with research objectives. Examine what conclusions the authors drew from their study and whether these conclusions answer the original question.

You should also pay attention to how the authors used findings to support their conclusions. For example, you can reflect on why their findings support that particular inference and not another one. Moreover, more than one conclusion can sometimes be made based on the same set of results. If that’s the case with your article, you should analyze whether the authors addressed other interpretations of their findings .

Here are some useful questions you can use to analyze the discussion section:

- What findings did the authors use to support their conclusions?

- How do the researchers’ conclusions compare to other studies’ findings?

- How does this study contribute to its field?

- What future research directions do the authors suggest?

- What additional insights can you share regarding this article? For example, do you agree with the results? What other questions could the researchers have answered?

Now, you know how to analyze an article that presents research findings. However, it’s just a part of the work you have to do to complete your paper. So, it’s time to learn how to write research analysis! Check out the steps below!

1. Introduce the Article

As with most academic assignments, you should start your research article analysis with an introduction. Here’s what it should include:

- The article’s publication details . Specify the title of the scholarly work you are analyzing, its authors, and publication date. Remember to enclose the article’s title in quotation marks and write it in title case .

- The article’s main point . State what the paper is about. What did the authors study, and what was their major finding?

- Your thesis statement . End your introduction with a strong claim summarizing your evaluation of the article. Consider briefly outlining the research paper’s strengths, weaknesses, and significance in your thesis.

Keep your introduction brief. Save the word count for the “meat” of your paper — that is, for the analysis.

2. Summarize the Article

Now, you should write a brief and focused summary of the scientific article. It should be shorter than your analysis section and contain all the relevant details about the research paper.

Here’s what you should include in your summary:

- The research purpose . Briefly explain why the research was done. Identify the authors’ purpose and research questions or hypotheses .

- Methods and results . Summarize what happened in the study. State only facts, without the authors’ interpretations of them. Avoid using too many numbers and details; instead, include only the information that will help readers understand what happened.

- The authors’ conclusions . Outline what conclusions the researchers made from their study. In other words, describe how the authors explained the meaning of their findings.

If you need help summarizing an article, you can use our free summary generator .

3. Write Your Research Analysis

The analysis of the study is the most crucial part of this assignment type. Its key goal is to evaluate the article critically and demonstrate your understanding of it.

We’ve already covered how to analyze a research article in the section above. Here’s a quick recap:

- Analyze whether the study’s purpose is significant and relevant.

- Examine whether the chosen methodology allows for answering the research questions.

- Evaluate how the authors presented the results.

- Assess whether the authors’ conclusions are grounded in findings and answer the original research questions.

Although you should analyze the article critically, it doesn’t mean you only should criticize it. If the authors did a good job designing and conducting their study, be sure to explain why you think their work is well done. Also, it is a great idea to provide examples from the article to support your analysis.

4. Conclude Your Analysis of Research Paper