- Open Search Close Search

Sarah McAra

Exploring public leadership in the blm era: a case study on stop and search.

An overview of a recent case study our MPP students tackled in class.

Last year, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement focused global attention on the deep-seated challenges of racism and police violence in Black communities, with activists around the world advocating for racial justice on an unprecedented scale. This is a major challenge of our time – one that demands the attention of future public policy leaders. It’s a pressing policy issue, an important leadership issue, and, for many, a deeply personal issue.

At the Case Centre on Public Leadership , we recognised that the Blavatnik School’s Master of Public Policy (MPP) students would want to engage with the issues raised by the BLM movement. But rather than discuss the movement in general, we wanted to incorporate these important topics into the students’ education in public leadership. We used our case study format to turn these challenges into managerial dilemmas, enabling students to gain the skills needed to address systemic inequalities in society. Collaborating with Professor Chris Stone , an expert in criminal justice reform, we drew on our faculty’s research to develop an in-depth case study around race and policing.

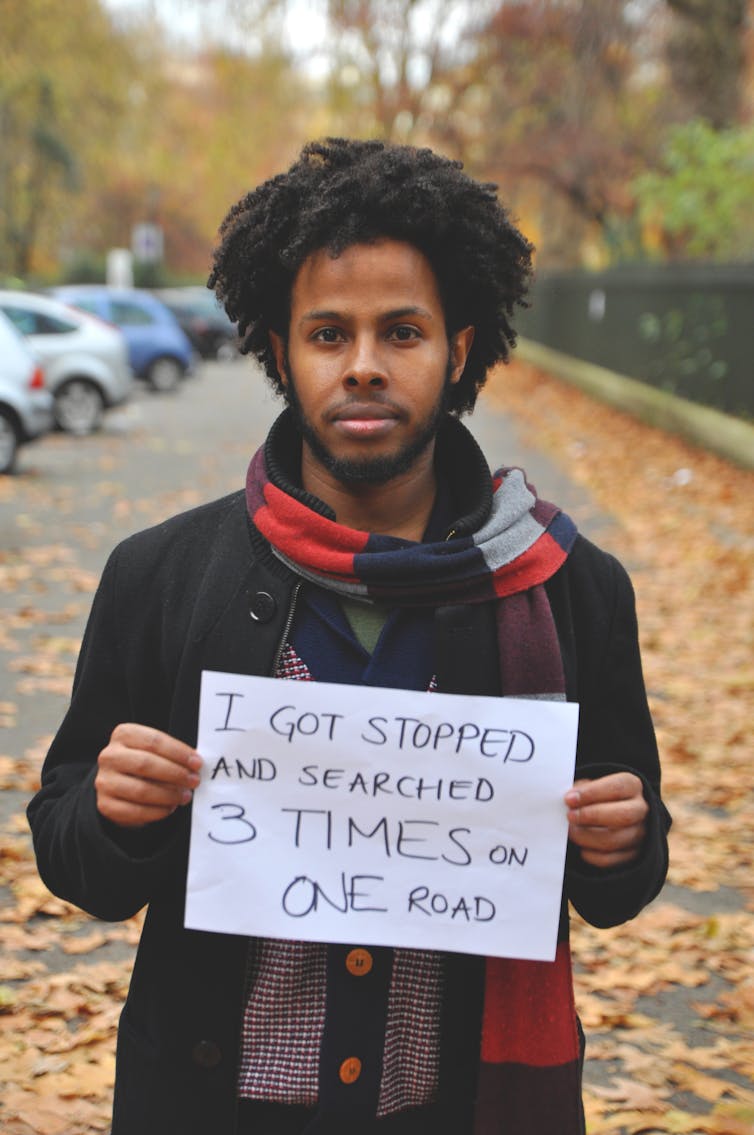

The case study explores the issues by examining the policy of stop and search , a long-contentious police power in the UK that allows officers to confirm or allay suspicions without first making arrests. The case is set in London in June of 2020, as national Covid-19 lockdown measures start to ease and BLM protests continue to spread. London’s latest stop and search statistics have just been released, showing that the Metropolitan Police (the Met) conducted 44,000 searches in May , an eight-year monthly high . London’s stop and search numbers had started to fall a decade before, but then increased in 2017/18 in an attempt to address rising knife crime. Yet this spike in May is still unexpected, nearly double the number seen in May the year prior. And beyond the sheer number of searches, the data also show that Black Londoners were searched at four times the rate of white Londoners. This rate of disproportionality has persisted for decades, eroding Black communities’ trust and confidence in the police. Against the backdrop of the BLM protests, these trends reignite concerns of racial profiling and institutional racism at the Met.

The case focuses around the then Commissioner of the Met, Cressida Dick, who must decide how to respond to the spike in searches. While Commissioner Dick helds a unique role as the most powerful police officer in the UK, responsible for more than 30,000 officers, her dilemma is a common one: What do you do when you’re the head of a public service organisation that has lost the trust and confidence of key stakeholders?

This is the question that students got to consider in the classroom, discussing the case over two days in sessions led by Professor Stone and Professor Karthik Ramanna , director of the MPP and the Case Centre. On the first day, students focused on diagnosing the situation: what’s going on, and how did we get here? One of the challenges of this session was making sense of the history and evidence around the policy. Students found that two people could look at the same data on stop and search, such as the number of stops that find a weapon or other prohibited item, and come to different conclusions around the policy’s effectiveness and use across ethnic groups. And even while academic evidence tends to suggest that stop and search does not reduce crime, the majority of officers insist from their experience on the streets that it is a powerful tool for crime prevention and reduction. So while the policy has been contentious for decades over its disproportionate impact on Black and minority ethnic communities, it still enjoys widespread support in London. By exploring these details, students started to understand the complexities of the debate around the policy and the challenges of reform.

On the second day, students focused on finding solutions through a simulation. Each student was randomly assigned a role of one of the many stakeholders engaged in the issue: the Met Commissioner, the Mayor of London, an officer representative, an activist group representative, and so on. The Commissioner had to work with the other stakeholders to develop an action plan with concrete next steps. Through this exercise, students got to experience the challenges of uniting diverse, and often conflicting, views. It’s not a case where just internal and external perspectives are at odds; even views within the Met differ over how stop and search is used in Black communities, while members of the public voice diverse opinions on the matter. The simulation required careful communication, strategic negotiation, and some innovative thinking to find solutions that unite these perspectives and help to move forward. Finally, after presenting their own action plans, the students got to hear from the Commissioner herself, who spoke about her career in policing.

Through the case discussions, students were able to engage with our faculty’s research on criminal justice reform while also developing important leadership skills. These future leaders will be able to draw on these skills and knowledge to help rebuild trust with communities and address systemic inequalities in society.

Sarah McAra is senior case writer at the Blavatnik School’s Case Centre on Public Leadership. See more on the case studies and how they work on the Case Centre on Public Leadership 's page.

Using our cases

Stop & search in London in the summer of COVID is available on the Case Centre for instructors wishing to use it in their own teaching.

Photo credit: iStock

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Featured Content

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Criminology

- About the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, setting the scene, the deterrent effect of s&s, findings from existing studies, research design, discussion and conclusions, technical appendix.

- < Previous

Does Stop and Search Deter Crime? Evidence From Ten Years of London-wide Data

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Matteo Tiratelli, Paul Quinton, Ben Bradford, Does Stop and Search Deter Crime? Evidence From Ten Years of London-wide Data, The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 58, Issue 5, September 2018, Pages 1212–1231, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azx085

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this article, we used ten years of police, crime and other data from London to investigate the potential effect of stop and search on crime. Using lagged regression models and a natural experiment, we show that the effect of stop and crime is likely to be marginal, at best. While there is some association between stop and search and crime (particularly drug crime), claims that this is an effective way to control and deter offending seem misplaced. We close the discussion by suggesting that, first, in a legal sense the key issue is that each and every stop should be justified in itself, not in that it has some putative wider effect on crime, and, second, in a sociological sense, our findings support the idea that stop and search is a tool of social control widely defined, not crime-fighting, narrowly defined.

Use of police powers to stop and search (S&S) members of the public has fallen significantly in England and Wales over the last few years. The number of recorded searches in 2014/15 was approximately 541,000 down by 58 per cent from a peak of almost 1 million in 2008/9 ( Home Office 2015 ). Yet use of the power remains a controversial issue. The decline in recorded searches has not be accompanied by a similar reduction in the ethnic disproportionality in their application; in 2014/15, people who were identified as Black or Black British were still four times more likely to be searched than their white counterparts ( Home Office 2015 ). S&S can still trigger significant reactions from individuals and groups who experience or observe its use, and wider social and political debates, as current disproportionalities entrench and interact with previous evidence of bias and discrimination.

Our focus in this article is not on ethnic disproportionality in S&S, which has been well documented elsewhere ( Bowling and Phillips 2007 ; Equality and Human Rights Commission 2010 ; Quinton 2015 ; Bradford and Loader 2016 ). Nor are we concerned with the wider social and cultural ‘meaning’ of stop and search—as a tool of social control ( Choongh 1997 ; Bradford and Loader 2016 ), for example—although we return to this question in the conclusion. Rather, we are concerned with whether S&S deters crime. This is a salient issue for two reasons. First, despite reductions in its use, S&S remains one of the most widely used formal police powers. Yet little is known about its effect on crime ( Delsol 2015 ), particularly in a UK context. Second, it remains a commonplace of media and police accounts of S&S—particularly in relation to its recent reduction in use—that S&S ‘must’ affect crime. While the law governing S&S tends to revolve around the investigation of crime, there is no doubt that police officers and many observers of police activity take a broader view, believing that S&S has a deterrent effect. This makes consideration of its likely effect on crime a pressing policy concern.

To address this, we use ten years’ worth of S&S, crime and other data from London, aggregated at the borough level, and we take two distinct analytical approaches. First, we utilize fixed-effect regression models estimating the lagged effect of S&S on crime. Second, interrupted time-series analysis is used to explore the potential effect of the sudden rise in the use of ‘suspicion-less’ or authorized searches that occurred from 2007 to 2011. We find that S&S has only a very weak and inconsistent association with crime. While there is some correlation, most notably in relation to drug offences, we conclude that the deterrent effect of S&S is likely to be small, at best.

The ‘power’ of S&S in England and Wales comprises a range of powers governed by several pieces of legislation that enable officers to search for a range of items. Most well known is section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (hereafter s1), which enables searches for stolen goods and a range of prohibited items (such as offensive weapons). Additional powers include those granted under section 23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (s23) for controlled substances; section 47 of Firearms Act 1968 (s47) for firearms; section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 (s60) to prevent acts of serious violence; and section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000 (s44, since repealed) to prevent acts of terror. For the purposes of this article, we distinguish between two broad groups of powers—those that require officers to have ‘reasonable suspicion’ before conducting a search (s1, s23 and S47) and those that do not but, instead, require them to be authorized to carry out searches in a defined area for specified time period (s60 and s44).

Although S&S has come to be one of the most emblematic, indeed arguably foundational powers, of the police in England and Wales, the extent of its uses varies markedly across time and place ( Bradford 2017 ). The data used in this article cover London during the period 2004–14. By way of an introduction, Figure 1 shows that while recorded crime declined gradually but consistently over this period, S&S showed marked variations month-on-month and over the ten-year study period. The recorded use of reasonable suspicion searches increased between 2004 and 2010 and then went into steady decline. Authorized searches that do not require officers to have reasonable grounds were rarely used before the middle of 2007; after that point their use markedly increased, reaching a peak in 2008, before going into steady decline. After a further peak in August 2011 (which coincided with the London riots), usage again became rare.

Trends in searches and crime (Metropolitan Police, 2004–14). Susceptible crime = those crimes that are susceptible to detection by S&S

We are concerned in this article with the deterrent effect of S&S on potential offenders; specifically, whether a marginal change in the S&S rate in an area can be linked to a subsequent change in the crime rate in the same area. It is worth reiterating that this is not the legal justification for most searches. While the authorized search powers are framed in legislation explicitly in terms of prevention, more commonly used reasonable suspicion powers are framed as investigatory tools. 1 However, considering the mechanisms by which S&S might reduce crime, and given the significant conceptual overlap between apprehension and deterrence as well as the nature of public and policy debate around S&S (very often framed in terms of deterrence), we believe that this is a justifiable starting point for our analysis.

Deterrence theory distinguishes between different ‘varieties’ of deterrence. In the case of S&S, the most pertinent relate, first, to the certainty of apprehension as a lever for deterring potential offenders. It is usually argued that what deters people from committing a crime is not the severity of any punishment that may ensue, nor the speed with which it will be delivered, but their perception of how likely they are to be caught ( Apel and Nagin 2011 ; Nagin 2013 ; see also Pratt et al. 2009 ). If it is to have a deterrent effect, S&S, must make acts of crime appear riskier to potential offenders by suggesting that they are likely to be caught if they do break the law.

Second, deterrence theory rests on the contrast between specific and general deterrence: to whom is the risk of apprehension communicated? Specific deterrence functions at the individual level, referring here to the effect of S&S experiences on offenders—and others—who have been interdicted by police. A proportion of those searched will be arrested or handed an alternative sanction such as a cannabis warning or fixed penalty notice. Having been caught ‘red-handed’, it naturally seems possible that these individuals might be deterred from committing a crime in the future. Likewise, simply being stopped and searched, even when one has not broken any law, may have a future deterrent effect on one’s behaviour. General deterrence, by contrast, refers to the effect S&S awareness might have on the behaviour of the general population who see or hear about this type of police activity or who merely know the police can carry out S&S. Witnessing or having some knowledge about S&S may shift people’s risk perceptions, leading them to believe, for example, that police are effective ‘sentinels’ ( Nagin et al. 2015 ) who are capable of apprehending offenders.

Deterrence theory is thus premised on the existence of rational potential offenders who undertake ‘a conscious weighing of the benefits and costs of offending contingent on and constrained by factors of the environment [and] situation’ ( Nagin et al. 2015 : 79). S&S activity comprises part of the environments and situations within which potential offenders make decisions, and it exerts an influence on their behaviour by making offending riskier. This argument involves two core assumptions: that people are aware of the level of police activity in their environment and that they update their risk perceptions as a result of experiencing or knowing about such activity, such that an increase in objective risk of sanction (more policing) is linked to an increase in subjective risk. If these assumptions do not hold it is hard to envisage how S&S can have a deterrent effect on crime.

While there is debate within the literature ( Apel 2013 ; Pickett and Roche 2016 ), the balance of evidence suggests it is unlikely that ‘criminal justice policies or police activities exert…influence on individual’s perceptions of arrest risk’ ( Picket and Roche 2016 : 729) in any widespread or consistent manner (see also Paternoster 2010 ). There is little reason to believe that there is an awareness of the general volume, distribution or nature of police activity such as S&S, casting doubt on the idea that S&S has a general deterrent effect on crime. To put it another way ‘it is not clear how or even if individuals update their subjective probabilities [of sanction risk] in response to changes in objective sanction risk’ ( Apel 2013 : 86). If police change the objective risk of sanction by increasing the level of S&S in an area, this will not necessarily lead to changes in the behaviour of people in that area, since they do not ‘notice’ police activity in such a way that would lead them to reassess how risky they thought certain behaviours were.

There is however evidence on specific deterrence that suggests people update their risk perceptions as a result of personal and perhaps vicarious experience of arrest or apprehension ( Apel 2013 ). Notably, it seems that the extent of such updating (the size of the shift in perceived risk) is greatest among those who commit crime, do not get caught, and consequently lower their risk perceptions, thus making them more likely to offend in the future ( Pogarsky et al. 2005 ; Matsueda et al. 2006 ). It is therefore possible that a decline in S&S rates, in as much as it results in a reduction in the number of people apprehended after offending, 2 may have an upward effect on crime rates because it diminishes the perceived risk of sanction among those who ‘get away’ with crimes (i.e. who could have been searched while intending to or having committed an offence but were not). By contrast, it is somewhat less clear that individuals who are searched and/or sanctioned by police update their risk perceptions accordingly (i.e. are led to believe they are likely to be searched and/or sanctioned again in the future). Piliavin et al. (1986) , for example, found that there was no correlation between their respondents’ prior arrest records and a measure of the perceived risk of formal sanction (see also Kleck et al. 2005 ). There may thus be an asymmetry in the potential effect of S&S on people disposed to offend. Other studies, however, report broadly ‘symmetrical’ effects of prior arrests on updating (e.g. Lochner 2007 ; Anwar and Loughran 2011 ), suggesting that people who are arrested do update their risk perceptions accordingly.

It is also possible that S&S has a ‘disruptive’ effect that does not fit neatly into deterrence theory, but rather, situational crime prevention. First, use of the power(s) in an area may make it harder for offenders to offend—for example by motivating the ‘stashing’ rather than carrying of knives—and thus disrupt their activity by delaying, displacing or reducing its severity. Second, an officer may search someone for ‘going equipped’: they had not yet stolen something, but were actively planning to do so. Ignoring for the moment that a search has created a possession offence, the officer has prevented future crime. Such situations are better described as disruption rather than deterrence because the motivation of the offender is unaffected, but, situationally, they cannot commit their planned crime.

A further complicating factor is that not all crimes are equally ‘susceptible’ to S&S ( Miller et al . 2000 ). At a general level, crimes in the categories of violence, robbery, burglary, theft and handling, drugs and some forms of criminal damage are generally considered susceptible, as they involve the carrying of items related to the offence (e.g. a weapon, stolen property, drugs). Other important categories, such as fraud, harassment/stalking and cybercrime, are by nature not susceptible to this form of police intervention. One implication here is that if attention is limited to the relationship between S&S and ‘all-crime’, then analysis may under-estimate its effect, and that consideration of specific crime types is required.

There is an important counterpoint to the discussion thus far. In contrast to the deterrence literature, there is significant evidence that targeted police strategies, most notably hotspots policing, can have an effect on crime ( Weisburd and Eck 2004 ; Braga et al. 2014 ). This is relevant in the current context because such strategies often contain increased use of S&S, either intentionally or simply as a result of deploying additional police officers (see for example Taylor et al. 2011 ). While the causal mechanisms behind the observed effects of hotspot policing on crime remain opaque, it seems that targeted S&S activity may reduce crime, presumably via some sort of specific deterrent effect. However, such strategies were not in common use in the Metropolitan Police during the period covered in this article. While small independent efforts may have been implemented at some times and places, we have no reason to believe that S&S activity was actively being targeted towards crime hotspots in a systematic and consistent manner across the police force area. Indeed, evidence suggests that it is people, not places, that are most commonly ‘targeted’ by officers for S&S ( Quinton 2011 ; Bradford and Loader 2016 ) and that officers’ perceptions of high-crime locations may not be accurate ( Ratcliffe and McCullagh 2001 ; Chainey and Macdonald 2012 ). It seems unlikely then that S&S, certainly when measured at a borough level, might have exerted an effect on crime via a focus on high-crime locations.

Given the discussion above, it is perhaps not surprising that existing studies of the effect of S&S (and related activities) on crime report very mixed findings. The foundational—and much critiqued—study in the field is Boydstun (1975) . A quasi-experiment conducted in the San Diego in the early 1970s found that the suspension of Field Interrogations (FIs) in one beat appeared to lead to an increase in ‘suppressible’ crime compared to a ‘business as usual’ control site and a beat where only specially trained officers were allowed to conduct FIs, but that there was no significant change in the total number of arrests across all three sites. Two more recent quasi-experimental studies are reported by McCandless et al. (2016) and MacDonald et al. (2016) . McCandless et al . used a retrospective design to explore the effect of Operation BLUNT 2 in London (a knife crime initiative involving a large increase in s60 searches in some Metropolitan Police boroughs). Using difference in differences analysis, which compared change in the boroughs where Operation BLUNT 2 was in place with change in those where it was not, they concluded that the police operation (i.e. a large increase in weapons searches) had no effect on police recorded crime; indeed, ambulance calls fell faster in those boroughs where there were smaller increases in searches.

MacDonald et al. (2016) used a similar design, this time based around Operation Impact in New York, which involved increasing the number of officers, Stop, Question and Frisks (SQFs) and arrests in hotspots (‘impact zones’). Different types of SQF appeared to have different effects. While an increase in those SQFs based on reasonable suspicion had no consistent association with crime, the increase in SQFs based on probable cause (a higher legal threshold linked to specific criminal behaviour) was associated with relative reductions in total reported crimes, assaults, burglaries, drug violations, misdemeanour crimes, felony property crimes, robberies and felony violent crimes in the impact zones. The authors, however, described the results as having ‘little practical importance’ ( MacDonald et al. 2016 : 9) because of the small size of the reductions and the fact that probable cause SQFs made up a tiny proportion of the overall increase in SQFs. Also, the reductions could not, in the main, be directly attributed to increases in ‘investigative stops’: MacDonald et al . note, echoing the wider literature on hotspots, that the precise cause of the observed effects from Operation Impact remained unclear.

Other studies have used time-series and associated techniques to examine observational data. J. Penzer’s unpublished analysis of Metropolitan Police data looked at whether S&S across London had lagged monthly effects on total recorded crime and street robbery. No underlying associations were found once a sudden upward ‘shock’ in total crime was taken into account. Smith et al. (2012) used city- and precinct-level data from New York to explore lagged weekly effects of SQF on nine types of recorded crime, concluding that SQF was negatively associated with four (vehicle crime, robbery, assault and rape) but not with the others. Notably, effects, even when statistically significant, were very small. For example, Smith et al . estimated that if SQF was 10 per cent higher in week 1, robbery would have been 0.09 per cent lower than predicted at the precinct level, and 0.03 per cent lower than predicted at the city level, in week 2 ( 2012 : 32). Rosenfeld and Fornango (2014) also used precinct data from New York, although this time aggregated at an annual level, and concluded that SQF had no significant effect on burglary or robbery once relevant confounds were taken into account. Fagan (2016) , again looking at New York, explored whether probable cause SQFs and reasonable suspicion SQFs had different effects on six crime types at the precinct level. He found that aggregates of both SQF types had significant negative two-monthly lagged effects on violent felonies, property felonies, drug crimes, weapon offences, other felonies and misdemeanours but that the effects were consistently larger when probable cause SQFs were examined on their own. The analysis also suggested the sharpest decreases in crime were associated with the highest concentrations of probable cause SQFs. Fagan thus concluded that targeted use of searches based on reasonable suspicion was unproductive, compared to those based on a higher standard of evidence, and add ‘nothing to the crime control efforts of law enforcement’ ( 2016 : 79).

Finally, Weisburd et al . (2015) used data aggregated at much lower levels temporally (days and weeks) and spatially (street segments) to again explore SQF in New York, in particular its potential contribution to a hotspots policing strategy. Looking at lagged weekly effects across the city, the authors found that SQF had a significant, albeit small, negative association with crime at the street segment level, although the size of the effect was variable across different boroughs (their analysis suggested that an extra 700,000 SQF would reduce crime by 2 per cent—2016: 47). They also looked at specific instances of SQF in the Bronx and found that these they were negatively associated with crime for up to five days afterwards. Weisburd et al ., therefore, concluded that SQF had a significant, if small, effect on crime when targeted intensively in high-crime locations (albeit this was an approach that had been ruled unconstitutional).

In sum, there is little agreement in the literature as to the existence, or likely size, of any effect of S&S on crime rates. Some studies report modest but significant effects, at least in relation to some crime types, while others report null findings. We cannot, in this article, provide a definitive answer to this apparent conundrum. Rather, we use London as a case study from which to add to this growing body of evidence.

Aims and hypotheses

This article examines whether the use of S&S by the Metropolitan Police reduced crime via a deterrent effect on potential offenders. Using borough-level data covering a ten-year period, we tested the following hypotheses:

H1 That overall S&S, under any power, was negatively associated with subsequent levels of total recorded crime.

H2 That overall S&S, under any power, was negatively associated with subsequent levels of specific types of recorded crime.

H3 That S&S under particular powers was negatively associated with subsequent levels of specific types of recorded crimes.

H4 That sudden changes in the use of s60 searches were associated with changes in violent crime.

The Metropolitan Police provided daily counts of recorded searches and particular categories of crime that might be susceptible to S&S for every borough in London from April 2004 to November 2014. While data on all 32 boroughs were provided, Westminster was excluded from the analysis presented here as it was an outlier in terms of its population size and number of recorded searches. 3

Separate counts were provided for the various powers. Daily crime counts were also provided for recorded drugs offences, non-domestic violent crime, burglary, robbery and theft, vehicle crime and criminal damage, which we aggregated into an overall count of total susceptible crime. To enable us to explore the specific relationship between S&S and violence further, we obtained counts of weapon-enabled non-domestic violent crime from the Metropolitan Police and of ambulance incidents related to ‘stab/shot/weapon wounds’ from the London Ambulance Service. In theory, the former should have been the sub-category of violence most susceptible to S&S, while the latter should have overcome some of the problems of violence not being reported to the police and not being included in the counts of recorded crime.

The counts were converted into rates per 100,000 residents to control for population and to better reflect the likelihood of an individual being searched by the police or becoming a victim of crime. 4 Table 1 presents summary of these data.

Descriptive statistics (per borough, per week)

There were two limitations to these data. First, we examine broad categories of crime. While the use of more specific crime types might have provided a better test of S&S, too many boroughs recorded no offences under each category, especially on a weekly basis, which complicated the type of analysis presented here. 5 It was also not possible, for example, to test whether S&S was associated with knife crime for this reason. Second, as the analysis relied mainly on police data, we could only analyse activities and crimes that were recorded by officers. For example, during this period, data were recorded about arrests from searches but not any other ‘positive outcome’ (e.g. fixed penalty notices).

It is also worth noting that we only look at the quantity of searches, not their ‘quality’ (e.g. the context in which they were performed or how they were conducted). It is highly likely that policing priorities and practices will have varied by borough and over time, and it is beyond the scope of this article to relate the results of our analysis to these variations. Our analysis therefore presents an average for the 31 boroughs over the ten-year study period and, as such, should be regarded as a ‘real world’ assessment of the effectiveness S&S rather than a test under ‘ideal conditions’.

We tested H1, H2 and H3 using regression analysis (the fourth was tested via a quasi-experimental design—see below). The regression analysis was complicated by the problem of reverse causality. Searches and crime are associated in many different ways, making it extremely difficult to untangle cause and effect, and as Figure 2 shows, there are five relationships of interest:

The potential relationships between searches and crime. It is possible that searches and crime respond to one another at different speeds. For example, offenders may respond quicker to more S&S than the police do to more crime

A. S&S levels and crime might influence one another in the same period (at either time 1 or time 2). For example, S&S might be carried out in response to higher crime, crime might be reduced by S&S, and/or crime might be increased by S&S if the searches led to new offences being discovered and recorded.

B. S&S levels (time 2) might be influenced by S&S in the previous period (time 1).

C. S&S levels (time 2) may respond to crime in the previous period (time 1).

D. Crime levels (time 2) might be influenced by crime in the previous period (time 1).

E. Crime levels (time 2) might be reduced by S&S in the previous period (time 1).

The challenge is, therefore, to show whether S&S had a lagged relationship with crime (E) above and beyond all other possible associations. In order to do this, we included the lagged crime rate and the current rate of S&S in all our models (essentially an autoregressive distributed lag (1,1) model). This controls for relationships A–D, but it also creates some statistical challenges that will be considered below.

The other important aspect of research design is the level of aggregation. Studies have examined the impact of searches annually ( Rosenfeld and Fornango 2014 ) and daily ( Weisburd et al. 2015 ). We chose months and weeks as a middle ground, which is justified on theoretical and methodological grounds. Theoretically, it seems somewhat implausible that people will adjust their beliefs about the likelihood of being searched on a daily basis. But equally, it is hard to imagine any deterrent mechanism working on a very long time scale, as people’s beliefs are likely to update more often than annually. Methodologically, it is significant that our data were collected at the borough level. Weisburd et al. ’s (2015) study used daily data but on a micro-geographic scale, where it is plausible that a daily surge in S&S could impact crime. With geographical units as big as ours, it would be almost impossible to cut through the noise in daily fluctuations. However, at the other extreme, modelling a yearly effect would require a very different statistical approach and many more control variables that were available to us. We therefore investigated the medium-term dynamics of the relationship between searches and crime: looking at the effect over weeks and months.

We developed a series of fixed effects regression models to test our first three hypotheses:

H1 Weekly and monthly models testing whether total susceptible crime was associated with total S&S under any power, on the basis that offenders may not have distinguished between different search powers.

H2 A series of weekly and monthly models exploring whether our six categories of crime were related to total S&S, for the same reason.

H3 A series of weekly and monthly models exploring whether the following crime types were affected by particular search powers, to which they were most likely to be susceptible to detection: drugs offence and s23 searches; non-domestic violent crime and s1 searches and s47 searches; burglary and s1 searches; robbery and theft and s1 (non-weapon) searches; vehicle crime and s1 (non-weapon) searches; and criminal damage and s1 (non-weapon) searches.

To enable this analysis, we converted the crime and S&S rates to natural logs to reduce skewness and to allow us to interpret coefficients as a percentage change in crime rate given a 1 per cent change in S&S rate (for clarity results table show the effects of a 10 per cent change in S&S rate). These were then aggregated by week in the first data set (31 boroughs × 554 weeks = 17,174 observations) and by month in the second (31 boroughs × 127 months = 3,937 observations).

We also controlled for several other factors. First, the level of overall police activity using counts of full-time equivalent police officers in each borough. 6 We preferred this proxy measure of police activity to a count of total arrests in each borough because, in the arrest data, ‘borough’ represents the custody suite that the arrestee was taken to, not the place of arrest. The allocation of arrestees to custody suites is organized centrally and depends on multiple factors such as cell availability, special operations and suites dedicated to certain offences. When custody suites are closed for repairs, boroughs register zero arrests (this happened in six boroughs during our data period, which would have been dropped from the analysis).

Second, our analysis took account of any unobserved characteristics of each borough (fixed effects). Third, all models included time-period fixed effects. This allowed us to control for seasonality, changes in Home Office counting rules or any other London-wide shocks to the crime rate. Fourth, we took account of long-term changes in crime rate within each borough by including borough-specific linear time trends. Finally, as we were mainly interested in testing the deterrent effect of S&S and because arrests resulting from searches could have been independently associated with crime, 7 we also controlled for the number of search-arrests at both time 1 and time 2 and t − 1. 8 See Technical Appendix for full model specification and estimation strategy.

Quasi-experimental Design

We explored our fourth hypothesis with a different approach. The sudden increase and decrease in use of s60 searches in the Metropolitan Police during our data period allowed us to conduct a quasi-experiment comparing the periods before and after s60 searches became common place. 9 We did not expect the increased use of s60 powers to have an instant impact and so it did not make sense to think of this as a one-off ‘treatment’. Instead, we examined whether the trend in non-domestic violent crime during the period when s60 powers were being used was significantly different to the trend in the preceding period. To be clear: if s60 powers were effective in reducing violence, then we would have expected the rate of decline in non-domestic violent crime to have increased in this period. We, therefore, performed an interrupted time-series analysis using Prais–Winsten regression to test this hypothesis. 10 We did not need to control for seasonality as both periods extended over multiple years. Furthermore, as s60 powers were not used each month in every borough, we had to aggregate the different panels together, looking at the effect across London as a whole.

Regression analysis

Table 2 presents a summary of the results across different crime types for both the monthly and weekly datasets (full tables of results are available from the lead author). We start by looking at the effect of S&S under all powers on total susceptible crime (H1). The results show that a 10 per cent increase in S&S was associated with a drop in susceptible crime of 0.32 per cent (monthly) or 0.14 per cent (weekly). Although statistically significant, this effect was extremely small. In addition, most of the effect that searches had on total crime seemed to come from the specific impact of searches on drug offences. When we excluded drug offences from the total crime rate and s23 searches from the S&S rate, the size of the effects halved in both the weekly and monthly models.

Summary results

All models estimated using fixed-effect estimator (OLS) with cluster-robust standard errors. Variables not shown: lagged dependent variable, number of full-time equivalent police officers, period fixed effects, borough-specific linear time trends, current rate of S&S, search-arrests in current period (time 2) and search-arrests in previous period (time 1).

a Net of all other searches.

Table 2 also shows the results of our tests of H2 and H3 for each crime type. The clearest results were for drug offences: a 10 per cent increase in rates of total S&S per month decreased recorded drug offences by 1.85 per cent. Again, this was stronger than the weekly effect of 0.64 per cent. We also estimated the net effect of s23 searches, controlling for all other searches at time 1 and time 2. This suggested that most of the effect at the monthly level came from s23 searches, although note we did not find corroborating evidence at the weekly level.

We struggled to find evidence of an effect of S&S on violent crime. The only statistically significant result was the net effect of s1 and s47 weapon searches at the weekly level, and the effect here was far smaller than the any of our other findings: a 10 per cent increase in S&S led to 0.01 per cent decrease in non-domestic violent crime. As a test of robustness, we also looked at weapon-enabled non-domestic violence and found similar nil results: no effect for all searches and a tiny, but statistically significant, effect for s1 and s47 searches. Moreover, when we used ambulance incident data for calls related to ‘stab/shot/weapon wounds’, we found no statistically significant results at all. Note that, to ensure comparability, we used the same type of linear model for these two alternative measures but, because of the large number of zeros for both (especially in the weekly data), these figures need to be treated with some caution.

The results for burglary were similarly inconsistent. At the weekly level, a 10 per cent increase in total searches seemed to reduce burglary by about 0.17 per cent. However, the effect was non-significant at the monthly level. By contrast, the net effect of s1 searches was only significant at the monthly level (there the effect of a 10 per cent rise in S&S would be a 0.47 per cent decrease). These effects were again very small and inconsistently significant and so must be treated with caution. There was also no evidence of an effect on robbery and theft (separately and together), vehicle crime or criminal damage.

One potential problem with our analysis is that of multiple comparisons. As we tested for so many associations, there was a chance that some of the statistically significant results reported above would have come about purely by chance. See the Technical Appendix for details on how we addressed this issue, which reinforces the sense that the effect of S&S on crime is marginal at best.

Quasi-experimental results

Recall that the sudden increase and decrease in s60 searches allows us to conduct a quasi-experiment comparing the periods before and after s60 searches became common place. As Table 3 and Figure 3 show, there was no statistically significant change in the trend in non-domestic violent crime between the period when s60 searches were used extensively and the period before. This result was robust to the inclusion of population data and officer numbers and to reasonable changes in the timing of the ‘interruption’. In fact, the rate of decline of non-domestic violent crime seemed, if anything, to have slowed (i.e. the coefficient for change to trend was positive and became significant once controls for population are added).

The impact of changes in s60 on violent crime

Estimated using Prais–Winsten regression with errors assumed to follow a first-order autoregressive process.

Interrupted time-series analysis of the effect of s60 searches on non-domestic violent crime

Overall, the analysis presented above suggests that, although S&S had a weak association with some forms of crime across London between 2004 and 2014, the effect was at the outer margins of statistical and social significance (H1). We found no evidence for effects on robbery and theft, vehicle crime or criminal damage, and inconsistent evidence of very small effects on burglary, non-domestic violent crime and total crime; the only strong evidence was for effects on drug offences (H2 and H3). When we looked separately at s60 searches, it did not appear that a sudden surge in usage had any effect on the underlying trend in non-domestic violent crime (H4). In other words, we found very little evidence to support any of our hypotheses.

The relationship between S&S and drugs, however, stands out in terms of its relative strength and consistency. This might be thought to provide compelling evidence of S&S having had a deterrent effect on this form of offending. However, there are several other plausible causal mechanisms that might explain the relationship we observe. A deterrent-based explanation assumes that drug users and dealers stop offending when perceived risk reaches a certain level. However, another possibility is that higher rates of S&S prompt people to change their behaviour to make it harder for officers to uncover drugs (e.g. being more cautious, by carrying smaller amounts and hiding them more carefully) or that people carrying drugs—especially hard drug users—are simply displaced to nearby areas that are less ‘hot’ in terms of police activity ( Wood et al. 2004 ; Small et al. 2006 ). Furthermore, police recorded crime data are unlikely to be the most reliable measure of drug crime. The number of recorded drug offences will depend largely on police activity that discovers people in possession of drugs and not on the underlying prevalence of drug use. This is not to say that S&S has no deterrent effect on drug crime, but clearly, more research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind the association described above.

It was also notable that the month-on-month relationship between S&S and crime was consistently stronger than the week-on-week relationship. One possible explanation is that people need to be exposed to higher levels of S&S for a longer period of time (particularly at the borough level) before they update their beliefs about the likelihood of being apprehended. As noted above, Weisburd et al. (2015) have suggested that SQF has a deterrent effect over a matter of days, but their study was focused at a very local level where it might be more reasonable to expect that people notice, and respond to, daily fluctuations in police activity.

Our results would seem to support, therefore, the idea that police activity—at least in the form of S&S—has relatively little deterrent effect. Indeed, assuming that longer-term incapacitation effects from S&S are minimal, it also appears that this form of policing has little effect on crime via other routes (e.g. disruption). Taken together, therefore, our results suggest that we should stop thinking about S&S as a tactic , which can be deliberately increased with a view to reducing crime, and focus instead on the appropriateness and legal justification of individual uses of the powers.

This last point goes to the crux of the matter. The downward trend in S&S that started in the second half of our study period has since continued; reasonable suspicion searches fell by 46 per cent between 2013/14 and 2015/16, a reduction that was echoed nationally ( Hargreaves et al. 2016 ). While there are many explanations for this drop, it is plausible that increased scrutiny had some effect on police practices. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (2013) and the Home Secretary (2014) both criticized the misuse of S&S and their assessments led to the introduction of the voluntary Best Use of S&S Scheme and national training ( Quinton and Packham 2016 ). These concerns were echoed by the incoming Commissioner of the Met, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe. The tone of this narrative, however, started to shift in response to increased knife crime in London from around 2015. On his retirement, Hogan-Howe questioned whether there might be a ‘floor’ in the reductions of S&S, after which it ceased to be effective in reducing crime: ‘…it’s possible we got too low in stop/search—a 70% [reduction] is a very big change’ ( 2017 ). More recently, his replacement Cressida Dick has, along with the Home Secretary, sought to encourage officers to have greater confidence in their powers, while emphasizing the need for them to act lawfully ( Dick 2017 ).

Our analysis concurs with most other studies in the field in concluding that increasing levels of S&S is likely to have at best a very marginal effect on emerging crime problems. This is not to claim, however, that individual searches do not produce useful ‘results’ (e.g. uncovering contraband and/or preventing a potential crime). It seems to us that the debates that swirl around S&S could usefully be refocused on the instances when the power is used, rather than on its alleged effect on crime in a general sense. As per most of the legislation governing S&S, the police should ask not whether S&S—as a tactic—contributes to crime reduction, but whether each and every search—as a power—is legally and operationally justified.

This is not to say that overall volume is unimportant, and the relationship between drugs and searches is again interesting here. The overall level of S&S is, to a large extent, determined by the number of searches for drugs—they represented over 60 per cent of all searches in 2015/16 ( Hargreaves et al. 2016 )—which provides something of a conundrum in the light of the results described above. On the one hand, drugs offences seem to be the crime type most affected by the volume of S&S. On the other hand, most drug searches are for cannabis possession ( Quinton et al. 2017 ), the reduction of which is unlikely to be a priority for any police force (and which comes with a range of well-known net-widening effects—Release 2013). While it is beyond the scope of the current article to consider this question in any depth, the effectiveness of the power needs to be considered in light of the ‘usefulness’ of its ends. Even if S&S is effective in deterring minor drug offending, is this reason enough for its continued use at current or indeed raised levels?

Finally, there is a deeper question that bears some reflection. We have little reason to believe that the results we have presented differ from what would have been found at other times and places in England, Wales and across the UK. It seems likely that S&S has never been particularly effective in controlling crime. Why, then, is the power still so commonly used? On one level, the answer is simple: police officers believe that S&S is a useful tool of crime control. Yet it is equally important to recognize that S&S is not solely about crime. As research over three decades has suggested, it is also a tool of order maintenance, used by police officers seeking to assert power and control in a situation or locale ( Smith and Gray 1985 ; Choongh 1997 ; Quinton 2011). S&S may also play a structural role linked to the basic function of police as an institution of social ordering: a way for police to discipline and ascribe identity to the populations they police ( Bradford and Loader 2016 ). The extent and distribution of its use may be affected by the location of the policed within social, economic and other hierarchies (c.f. Waddington et al . 2004 ). The benign interpretation of this wider function of S&S is that it can be a useful way for police to establish authority and maintain order. A less benign interpretation is, of course, that this is a power directed disproportionately towards people from marginal and excluded social groups, and which serves only to deepen their marginality ( McAra and McVie 2005 ; Bradford 2017 ). On both accounts, the question as to whether S&S has crime control properties is rather beside the point, as this is in some fundamental sense not what the power is ‘about’.

Our findings offer support to these arguments, at least in as much as they add to the weight of evidence that S&S is, at least in the aggregate, not about crime. If it were, we would expect a much stronger association between levels of S&S and crime than that which we identify in our models. However, police, politicians and public hold on to the idea that this is a useful way for police to ‘fight crime’. Indeed, S&S may be seen as effective because it is done by police, and police action, as opposed to inaction, is by definition effective in controlling crime. S&S is, if nothing else, a visible way of ‘doing something about crime’. Research that considers the ‘effectiveness’ of S&S, such as the present study, can therefore only address one part of a much bigger picture. But, it is an important part, not least because it might help to dispel some of these myths and refocus attention where it should properly be: on the fact that S&S should concern only the investigation of specific crimes and on the need to limit its use to appropriate situations to avoid damage to public trust and police legitimacy.

Achen , C . ( 2000 ), ‘ Why Lagged Dependent Variables Can Suppress the Explanatory Power of Other Independent Variables ’. Presented at the American Political Science Association, UCLA .

Alvarez , J. and Arellano , M . ( 2003 ), ‘ The Time Series and Cross-Section Asymptotics of Dynamic Panel Data Estimators ’, Econometrica , 71 : 1121 – 59 .

Google Scholar

Anwar , S. and Loughran , T. A . ( 2011 ), ‘ Testing a Bayesian Learning Theory of Deterrence Among Serious Juvenile Offenders ’, Criminology , 49 : 667 – 98 .

Apel , R . ( 2013 ), ‘ Sanctions, Perceptions and Crime: Implications for Criminal Deterrence ’, Journal of Quantitative Criminology , 29 : 67 – 101 .

—— ( 2015 ), ‘ On the Deterrent Effect of Stop, Question and Frisk ’, Criminology and Public Policy , 15 : 57 – 66 .

Apel , R. and Nagin , D. S . ( 2011 ), ‘ General Deterrence: A Review of the Recent Evidence ’, in J. Q. Wilson and J. Petersilia , eds, Crime and Public Policy , 4th edn, 411 – 36 . Oxford University Press .

Google Preview

Beck , N. and Katz , J. N . ( 2004 ), ‘ Time-Series-Cross-Section Issues: Dynamics, 2004 ’, available online at http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/politics/faculty/beck/beckkatz.pdf .

—— ( 2011 ), ‘ Modeling Dynamics in Time-Series–Cross-Section Political Economy Data ’, Annual Review of Political Science , 14 : 331 – 52 .

Benjamini , Y. and Hochberg , Y . ( 1995 ), ‘ Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing ’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) , 57 : 289 – 300 .

Bowling , B. and Phillips , C . ( 2007 ), ‘ Disproportionate and Discriminatory: Reviewing the Evidence on Police Stop and Search ’, The Modern Law Review , 70 : 936 – 61 .

Boydstun , J . ( 1975 ), San Diego Field Interrogation: Final Report . Police Foundation .

Bradford , B . ( 2017 ), Stop and Search and Police Legitimacy . Routledge .

Bradford , B. and Loader , I . ( 2016 ), ‘ Police, Crime and Order: The Case of Stop and Search ’, in B. Bradford , B. Jauregui , I. Loader and J. Steinberg , eds, The Sage Handbook of Global Policing , 241 – 60 . Sage Publications .

Braga , A. , Papachristos , A. and Hureau , D . ( 2014 ), ‘ The Effects of Hot Spots Policing on Crime: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis ’, Justice Quarterly , 31 : 625 – 48 .

Chainey , S. and Macdonald , I . ( 2012 ), Stop and Search, the Use of Intelligence and Geographic Targeting: Findings from Case Study Research . National Policing Improvement Agency .

Choongh , S . ( 1997 ), ‘ Policing the Dross: A Social Disciplinary Model of Policing ’, British Journal of Criminology , 38 : 623 – 34 .

Delsol , R . ( 2015 ), ‘ Effectiveness ’, in R. Delsol and M. Shiner , eds, Stop and Search: An Anatomy of a Police Power , 79 – 101 . Palgrave Macmillan .

Dick , C . ( 2017 ), ‘ I Want Officers to Feel Confident to Use This Power ’, The Times , 9 August, available online at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/cressida-dick-metropolitan-police-commissioner-i-want-officers-to-feel-confident-to-use-this-power-x8xrkv6hf (accessed 1 October 2017 ).

Equality and Human Rights Commission ( 2010 ), Stop and Think: A Critical Review of the Use of Stop and Search Powers in England and Wales . EHRC .

—— ( 2013 ), Stop and Think Again: Towards Race Equality in Police PACE Stop and Search . EHRC .

Fagan , J . ( 2016 ), ‘ Terry’s Original Sin ’, University of Chicago Legal Forum , 2016 : 43 – 97 , Available online at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2016/iss1/3 .

Gelman , A. , Hill , J. and Yajima , M . ( 2012 ), ‘ Why We (Usually) Don’t Have to Worry About Multiple Comparisons ’, Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness , 5 : 189 – 211 .

Hamilton , J. D . ( 1994 ), Time Series Analysis , 1st edn. Princeton University Press .

Hargreaves , J. , Linehan , C. and McKee , C . ( 2016 ), Police Powers and Procedures, England and Wales, Year Ending 31 March 2016 . Home Office .

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary ( 2013 ), Stop and Search Powers: Are the Police Using Them Effectively and Fairly? HMIC .

Hogan-Howe , B . ( 2017 ), Interview by Davis, E. Newsnight [Television Broadcast] . BBC .

Home Office and College of Policing ( 2014 ), Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme . Home Office .

Home Office ( 2015 ), Police Powers and Procedures, England and Wales, Year Ending 31 March 2015 . Home Office .

Home Secretary ( 2014 ), Stop and Search: Comprehensive Package of Reform for Police Stop and Search Powers . Oral Statement to Parliament, 30 April 2014. Home Office .

Keele , L. and Kelly , N. J . ( 2006 ), ‘ Dynamic Models for Dynamic Theories: The Ins and Outs of Lagged Dependent Variables ’, Political Analysis , 14 : 186 – 205 .

Kleck , G. , Sever , B. , Li , S. and Gertz , M . ( 2005 ), ‘ The Missing Link in General Deterrence Research ’, Criminology , 43 : 623 – 59 .

Lochner , L . ( 2007 ), ‘ Individual Perceptions of the Criminal Justice System ’, American Economic Review , 97 : 444 – 60 .

MacDonald , J. , Fagan , J. and Geller , A . ( 2016 ), ‘ The Effects of Local Police Surges on Crime and Arrests in New York City ’, PLoS ONE , 11 : 1 – 13 .

Matsueda , R. L. , Kreager , D. A. and Huizinga , D . ( 2006 ), ‘ Deterring Delinquents: A Rational Choice Model of Theft and Violence ’, American Sociological Review , 71 : 95 – 122 .

McAra , L. and McVie , S . ( 2005 ), ‘ The Usual Suspects?: Street-life, Young People and the Police ’, Criminal Justice , 5 : 5 – 36 .

McCandless , R. , Feist , A. , Allan , J. and Morgan , N . ( 2016 ), Do Initiatives Involving Substantial Increases in Stop and Search Reduce Crime? Assessing the Impact of Operation BLUNT 2 . Home Office .

Miller , J. , Bland , N. and Quinton , P . ( 2000 ), The impact of stops and searches on crime and the community . Home Office .

Nagin , D . ( 2013 ), ‘ Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century ’, in M. Tonry , ed., Crime and Justice: A Review of Research , Vol. 42 , 199 – 264 . University of Chicago Press .

Nagin , D. , Solow , R. M. and Lum , C . ( 2015 ), ‘ Deterrence, Criminal Opportunities and Police ’, Criminology , 53 : 74 – 100 .

Nickell , S . ( 1981 ), ‘ Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects ’, Econometrica , 49 : 1417 – 26 .

Paternoster , R . ( 2010 ), ‘ How Much Do We Really Know About Criminal Deterrence ?’, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology , 100 : 765 – 824 .

Pickett , J. T. and Roche , S. P . ( 2016 ), ‘ Arrested Development. Misguided Directions in Deterrence Theory and Policy ’, Criminology and Public Policy , 15 : 727 – 51 .

Piliavin , I. , Gartner , R. , Thornton , C. and Matsueda , R. L . ( 1986 ), ‘ Crime, Deterrence, and Rational Choice ’, American Sociological Review , 51 : 101 – 19 .

Pogarsky , G. Kim , K. and Paternoster , R . ( 2005 ), ‘ Perceptual Change in the National Youth Survey: Lessons for Deterrence Theory and Offender Decision-Making ’, Justice Quarterly , 22 : 1 – 29 .

Pratt , T. , Cullen , F. , Blevins , K. , Daigle , L. and Madensen , T . ( 2009 ), ‘ The Empirical Evidence of Deterrence Theory: A Meta-analysis ’, in F. Cullen , J. Wright and K. Blevins , eds, Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory . Transaction Publishers .

Quinton , P . ( 2011 ), ‘ The Formation of Suspicions: Police stop and Search Practices in England and Wales ’, Policing and Society , 21 : 357 – 368 .

Quinton , P . ( 2015 ), ‘ Race Disproportionality and Officer Decision-Making ’, in R. Delsol and M. Shiner , eds, Stop and Search: An Anatomy of a Police Power , 57 – 78 . Palgrave Macmillan .

Quinton , P. , NcNeill , A. and Buckland , A . ( 2017 ), Searching for Cannabis: Are Grounds for Search Associated with Outcomes? College of Policing .

Quinton , P. and Packham , D . ( 2016 ), College of Policing Stop and Search Training Experiment: An Overview . College of Policing .

Ratcliffe , J. and McCullagh , M . ( 2001 ), ‘ Chasing Ghosts? Police Perception of High Crime Areas ’, British Journal of Criminology , 41 : 330 – 41 .

Rosenfeld , R. and Fornango , R . ( 2014 ), ‘ The Impact of Police Stops on Precinct Robbery and Burglary Rates in New York City, 2003–2010 ’, Justice Quarterly , 31 : 96 – 122 .

Small , W. , Kerr , T. , Charette , J. , Schechter , M. and Spittal , P . ( 2006 ), ‘ Impacts of Intensified Police Activity in Injection Drug Users: Evidence from an Ethnographic Investigation ’, International Journal of Drug Policy , 17 : 85 – 95 .

Smith , D. J. and Gray , J . ( 1985 ), Police and People in London: The PSI Report . Policy Studies Institute .

Smith , D. , Purtell , R. and Guerrero , S . ( 2012 ), Is Stop, Question and Frisk an Effective Tool in the Fight Against Crime ? Paper presented at the Annual Research Conference of the Association of Public Policy and Management : Baltimore, Maryland, USA .

Taylor , B. , Koper , C. and Woods , D . ( 2011 ), ‘ A Randomized Controlled Trial of Different Policing Strategies at Hot Spots of Violent Crime ’, Journal of Experimental Criminology , 7 : 149 – 81 .

Waddington , P. A. J. and Stenson , K. and Don , D . ( 2004 ), ‘ In Proportion: Race, and Police Stop and Search ’, British Journal of Criminology , 44 : 889 – 914 .

Weisburd , D. and Eck , J . ( 2004 ), ‘ What Can Police Do to Reduce Crime, Disorder, and Fear ?’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 593 : 42 – 65 .

Weisburd , D. , Wooditch , A. , Weisburd , S. and Yang , S.-M . ( 2015 ), ‘ Do Stop, Question, and Frisk Practices Deter Crime? Evidence at Microunits of Space and Time ’, Criminology and Public Policy , 15 : 31 – 56 .

Wood , E. , Spittal , P. , Small , W. , Kerr , T. , Li , K. , Hogg , R. , Tyndall , M. , Montaner , J. and Schechter , M . ( 2004 ), ‘ Displacement of Canada’s Largest Public Illicit Drug Market in Response to a Police Crackdown ’, Canadian Medical Association Journal , 170 : 1551 – 56 .

Wooldridge , J. M . ( 2003 ), Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach . South-Western College Publishing .

PACE Code of Practice A states that the purpose of S&S is ‘to enable officers to allay or confirm suspicions about individuals without exercising their power of arrest’ ( Home Office and College of Policing 2014 : para 1.4).

Recall that a non-trivial proportion of all arrests result from an S&S. For example, in 2014/15, there were 950,000 arrests for notifiable offences in England and Wales; over the same period, 75,000 arrests resulted from searches conducted under s1 PACE and associated legislation ( Home Office 2015 ).

All models were reproduced including Westminster, with little effect on the results.

The rates were based on mid-year population estimates for each borough from the ONS and splined to produce monthly and weekly estimates.

Attempts to use negative binomial models were complicated by the number of variables and, indeed, we could not make those models converge.

These data were provided by the Metropolitan Police with yearly totals that were linearly interpolated to monthly and weekly figures.

For example, crime levels might have been influenced by search-arrests in the same period (if they resulted in new crimes being discovered and recorded) and by previous search-arrests (if they resulted in offenders being incapacitated).

We also experimented with controlling for unemployment but did not find any statistically significant effects and, as it did not affect our results, we have not included it in the models presented here.

We chose not to extend this analysis into the third period after 2011 (when s60 use subsided) because it would have been almost impossible to decide on a theoretically appropriate end-point for this period. As Figure 3 shows, after the end of 2011, non-domestic violent crime continued to decline and, although it increased from the middle of 2013, it seems unlikely that this was an 18-month lagged effect of reduced s60 usage.

The Durbin–Watson statistics revealed positive serial correlation.

We experimented with alternative lag specifications, none of which removed the residual serial correlation.

Estimates for the serial correlation coefficient in our models obtained by Lagrange multiplier tests show that they were around or just above the levels tested by Keele and Kelly (2006) .

Our final regression model is described by the following equation:

where i = borough, t = month/week, Y i , t is the current crime rate, X i , t is the current rate of S&S, X i , t − 1 is the rate of S&S in the previous period, Y i , t − 1 is the crime rate in the previous period, A i , t is the number of search-arrests in the current period, A i , t − 1 is the number of search-arrests in the previous period, P i , t is estimated police numbers, D i is a 1 × N vector of dummy variable for each borough, L i , t is a 1 × N vector of borough-specific linear time trends, T t is a 1 × T vector of dummy variables for each month/week and e it is the error term. (The models looking at specific search powers also included the rate of all other search powers at both time periods so that we can look at the effect of e.g. s23 searches net of all other searches.)

Estimation strategies

Including a lagged dependent variable in our fixed-effect models could create estimation problems because it renders OLS inconsistent. Stephen Nickell (1981) demonstrated this inconsistency for fixed t , but showed that the bias disappears as t increases. Given the large number of time periods in our two datasets (554 and 127), we are confident that Nickell bias need not worry us. However, our models also exhibited varying degrees of first-order serial correlation, even with the lagged dependent variable. 11 The adequacy of OLS estimation in these circumstances is difficult to ascertain, however, various simulation studies ( Alvarez and Arellano 2003 ; Beck and Katz 2004 ; Keele and Kelly 2006 ) have indicated that it performs well compared to the leading alternative strategies, even with moderate levels of residual serial correlation. 12 We therefore employed the fixed-effect estimator (OLS), which allowed us to maintain a consistent estimation strategy ensuring comparability across all our models. As a robustness test, we also estimated the same models using (1) the Prais–Winsten transformation, which takes care of first-order serial correlation and produces a maximum likelihood estimate of the coefficients, and (ii) generalized least squares allowing for panel-specific autocorrelation with heteroskedastic and cross-sectional correlation ( Hamilton 1994 ; Wooldridge 2003 ; Beck and Katz 2011 ). The coefficients remained very similar across these three different estimation strategies.

Another concern was that a lagged dependent variable can ‘suppress the explanatory power’ of other variables ( Achen 2000 ). By de-trending the data using borough-specific time trends, we hoped to mitigate against this. Moreover, none of the coefficients for the lagged dependent variable reached the levels that are normally thought to be worrying. We also addressed heteroskedasticity and clustering of errors within boroughs by using cluster-robust standard errors. All analysis was performed using Stata 13.

Multiple comparisons

Because we tested for so many associations, there is a chance that some of the statistically significant results reported came about by chance. The classic response is to control the familywise error rate using the Bonferroni correction. This approach is highly conservative ( Gelman et al. 2012 ) and would mean rejecting the results for total crime at monthly and weekly levels, and the associations between drug offences and total searches and between burglary and total searches at the weekly level (the other results remain significant). A less conservative method is to control for the false discovery rate (the proportion of significant results that are false positives). Using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure and setting the false discovery rate to 0.05 ( Benjamini and Hochberg 1995 ), all of our results remained significant except the association between burglary and total searches at the weekly level.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3529

- Print ISSN 0007-0955

- Copyright © 2024 Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (formerly ISTD)

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thursday, 4 April

Search for news, browse news stories.

- All opinion

- All featured

We spent seven years observing UK police stop and search – here’s what we found

Dr Mike Rowe is a Lecturer in Public Sector Management in the University of Liverpool’s Management School . This article was also written by Dr Geoff Pearson at the University of Manchester

When the British politician Dawn Butler was stopped by police while travelling in a friend’s car earlier this year, she accused the police of institutional racism. The same thing happened to Olympic athlete Bianca Williams in July. In this context, it is extremely positive to hear that police traffic stops in London will be reviewed as part of a plan to “recognise and address the impact that some police tactics used disproportionately on black people is having”.

Such action is desperately needed. Black people in the UK are nine times more likely than white people to be stopped and searched by the police, recent government statistics show. Combined with a summer of Black Lives Matter protests, stop and search has rarely been out of the news and remains controversial.

Over the last seven years, we carried out observations with police officers from two English forces. While numbers of stop and searches have declined since 2014, the disproportionate use on young black men continues to cause concern.

Stop and search is a longstanding police power, the purpose of which is to allow police officers to find and seize prohibited items where they have reasonable grounds to believe that a person is carrying them. Much less scrutinised are powers to stop vehicles (used to stop Butler and Williams) under the Road Traffic Act and the practice of requiring people to “stop and account” – effectively asking them to explain who they are and what they are doing. Disproportionate use of stop and search against young black men can only be fully understood if we also consider the use of powers to stop vehicles and to stop and account.

As we outline in our new book , it was very rare for us to witness stop and searches that uncovered stolen or prohibited items: of the 146 people we observed being searched, only 12 such items were found. Although we observed some searches that were carried out without reasonable grounds, and some that went unrecorded, we did not witness overt racial discrimination or profiling in the use of the powers.

But our findings on stop and account and vehicle stop checks potentially shine a light on why these powers may disproportionately affect black people.

Reasonable grounds

Most of the searches we observed were not based on any specific intelligence that a person was carrying a stolen or prohibited item. Most followed a stop and account or vehicle stop check.

These were typically initiated by police officers as a result of seeing something that aroused their interest or suspicion; a pedestrian walking late at night in a high crime area, for example, or a group of young men in a sporty hatchback. In contrast to a stop and search, stopping a vehicle or detaining a citizen to ask questions requires neither grounds nor explanation.

Once a person or vehicle of interest had been stopped, the officer may then escalate this to a search, giving various reasons often based on a subjective view of suspicious demeanour. Officers might become suspicious if a person appears nervous and shifty, for example, or, conversely, if they appear overconfident.

In many cases we observed, officers identified the smell of cannabis as their reason to proceed to a search. In 2017, the College of Policing gave guidance that a “smell of cannabis” should no longer be grounds alone to conduct a search. The effect of this guidance has, however, been limited because officers can normally find other grounds to support a decision to conduct search where they wish to do so.

Unlike a stop and search, stop and accounts and vehicle stop checks do not need to be recorded, either formally or on a body-worn camera. But they are intrusive, and people who are subjected to frequent stops, even if these do not lead to a search, can understandably become upset.

Keeping a record

After the MacPherson report into the investigation of Stephen Lawrence’s murder in 1993 found the Metropolitan Police were “institutionally racist”, stop and accounts were recorded for several years.

This generated a record, but was burdensome in terms of time – the person already inconvenienced was expected to stand around while the officer took details and completed a form. From 2010, police forces were no longer required to make records of stop and account. Most (if not all) forces have stopped doing so.

Vehicle stops have never been recorded or reported externally, even though – in contrast to stop and account – it is a criminal offence not to comply. Nor does any reason need to be given for the decision to pull a vehicle over. Many of the vehicle stops that we observed could be justified for Road Traffic Act reasons or as a result of intelligence, but some were stopped for less clear reasons. Late at night, officers regularly stopped vehicles for no other reason than that they wanted to know who was out and about; a sporty model, or a car with young men on board, would arouse particular attention. It is easy to see how certain groups can become targets for repeated stops that may in turn escalate to a stop search.

Recording stop and accounts would probably place too much burden on both officers and members of the public. But we can see no reason why details of vehicle stop checks should not be recorded. This would create vital information about who is being stopped, when, and for what reason, which would enable a deeper understanding of why black people are so much more likely to be searched than white people.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

- Expert Opinion

- Featured Opinion

- The Conversation

- University home page

- Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

- University of Liverpool Management School

Stop and Search, National recommendations - April 2022

In 2020, we launched our thematic work on race discrimination, which enables us to independently investigate cases which would not ordinarily meet our threshold for investigation. Taking a thematic approach helps us to build the necessary body of evidence to drive real improvements in police practice by identifying both good practice and systemic issues, and in 2020 we used this approach to shape 11 formal learning recommendations to the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) following the study of five investigations featuring the use of stop and search.

In 2022, we published a report taking the next step on from that work, looking at learning that could be shared at a national level.

Our thematic recommendations and responses can be found below.

IOPC reference

Recommendations, legitimacy – reliability, quality, and specificity of intelligence.

Recommendation 1: to the National Police Chiefs' Council and College of Policing

The IOPC recommends that the NPCC and College of Policing work together to develop guidelines on how to safeguard people from a Black, Asian, or other minority ethnic background from being stopped and searched because of decision-making impacted by intelligence based upon assumptions, stereotypes, and racial bias, and mitigate the risks of discrimination.

The College’s Stop and Search Authorised Professional Practice (APP) and paragraph 2.2B of PACE Code A (2015) which are already in place set out the legal position and contain significant narrative relating to bias and discrimination, stating officers cannot use personal factors as the reason for stopping an individual.

However, taking into account evidence provided in the IOPC’s report, the APP will be revisited to ensure continued relevance by considering making reference to relevant information and intelligence more explicit. Also, it should make clear that stereotypes and bias should not be utilised. It is expected that this would:

Assist officers to form grounds for stops that are objectively reasonable given the information available; and Provide a framework to describe factors contributing to an officer genuinely suspecting they would find the item sought.

Further, it is considered important that those preparing problem profiles and similar products from the intelligence community also receive inputs and training around unconscious bias and stereotyping and this is refreshed regularly.

Legitimacy - drugs searches

Recommendation 2: to the Home Office

The IOPC recommends that the Home Office review what constitutes reasonable grounds for suspicion for cannabis possession. The review should consider whether smell of cannabis alone provides reasonable grounds for a stop and search and whether any changes are required to PACE Code A.

Not accepted