The Lean Post / Articles / Building People-Focused Problem-Solving Capacity

Problem Solving

Building People-Focused Problem-Solving Capacity

By Lean Leaper

September 21, 2020

While Lean promises robust solutions to the most pressing of problems, it’s core promise offers something even more enduring: the organizational capacity to frame and face problems in a dynamic manner. This piece explores how the best lean organizations discover that disciplined lean practice helps develop a capacity to explore, learn, and indeed, solve problems by everyone.

While Lean promises robust solutions to the most pressing of problems, it’s core promise offers something even more enduring: the organizational capacity to frame and face problems in a dynamic manner. Beyond the rewards of quick fixes, the best organizations discover that disciplined lean practice helps develop a capacity to explore, learn, and indeed, solve problems by everyone.

That’s why lean thinkers always stress the importance of focusing on the process of tackling problems over the gains of any one-time solution–to be vigilant about mindfully developing healthy habits with each turn of the cycle. Tracey Richardson shares a handful of key questions in support of this approach in Are You Having Problems with Your Problem-Solving? :

- Does every individual in your organization understand the Purpose of their work ?

- Is everyone utilizing the power of the Gemba ?

- Are you digging down to find root cause?

- Are you measuring in specific performance terms?

- Are you doing this everyday with everything you do?

She counsels people to replace kaizen “blitzes” (episodic events that frame problem-solving as something done on special occasions) with sustained daily efforts that become ingrained as healthy habits. “No labels, make it a way of business,” she says. This anchors the work in daily details, and guides improvers toward tangible targets.

Sustained lean practice inevitably focuses people on the specific details of any gap to be closed, say Jim Luckman and David Verble. In How a Problem-Solving Culture Takes Root , they advise people to “grasp the actual conditions of problem situations,” a principle that prevents people from jumping to conclusions with predetermined fixes.

While this may appear to be plain old common sense, they explain how this core principle grounds problem-solvers in a humble and open approach: “Rather than assume you know enough about the nature of a problem situation, go to the gemba (wherever the work processes are) and try to understand the sources of performance problems yourself. Look for and ask about the problems, often caused by variation in the way the work is being done.”

Indeed, starting with a commitment to the actual problems subsequently colors how you will interact with the people touching this problem. It will lead you to show respect for what your employees know, think, feel, and can do, they say; and drive you to ask open-ended questions in the spirit of inquiry as opposed to advocacy. It will also lead you to, per their advice, “pay attention to how employees talk to you (and each other) about problems.”

Following such a formal problem-solving process invariably develops teamwork, says John Shook, who has written often about the value of applying A3 thinking to challenges large and small. His terrific book Managing to Learn shares the iterative value of exposing how one person tackles a problem, emphasizing the mutual discovery of manager and managee as they address a focused (indeed, an increasingly narrow) problem.

In The A3 Process—Discovery at Toyota and What it Can Do For You , Shook talks about his experience that inspired the book, noting how one simple episode from his time at Toyota provided a scaffolding for a simple challenge that has helped illuminate the larger purpose of a PDCA -oriented leadership style:

“Where’s the damned file?” was a simple problem, but the value of the Process extended far beyond its face value of enabling us to find files faster. Education and learning were embedded in the Process of working on the A3 (the improvement project) itself. It exemplified learning through doing at its best. The more A3s I wrote, the better I became at the thought Process . Internalizing the thinking is the objective, not technical mastery of the format. The more cycles of reflection and learning that can be experienced, the better it is for the individual and for the organization.

The most fundamental use of the A3 is as a simple problem-solving tool. But the underlying principles and practices can be applied in any organizational settings. Given that the first use of the A3 as a tool is to standardize a methodology to understand and respond to problems, A3s encourage root cause analysis, reveal processes, and represent goals and action plans in a format that triggers conversation and learning. A good A3 has sound problem-solving — science — embedded inside, but it achieves much more, exemplifying this great quote by a great scientist:

“Science is built of facts the way a house is built of bricks, but an accumulation of facts is no more science than a pile of bricks is a house.” – Henri Poincaré

In exactly the same way, a good A3 is more than a collection of data that solves a problem — it tells a story that can coalesce an organization.

This generative quality of mutual problem-solving is highlighted in two recent Posts by John Shook and Isao Yoshino tracing the Kanri Noryoku Program (Kan-Pro) at Toyota. Tackling any problem was always linked to the eternal challenge of developing proficient managers who would learn through leading, and lead through learning (a reference to Katie Anderson’s new book on this topic.)

The two remind us once more of the need to lead mindfully, always open to the process of learning and developing while pursuing specific results: “One of the hallmarks of a successfully executed A3 process is that it is a collaborative activity (“it takes 2 to A3”), a learning process for everyone involved. For learner and teacher, senpai and kohai, sensei and deshi. The A3 paper is simply a convenience, a job aid to facilitate structured discovery.”

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.

Written by:

About Lean Leaper

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Revolutionizing Logistics: DHL eCommerce’s Journey Applying Lean Thinking to Automation

Podcast by Matthew Savas

Transforming Corporate Culture: Bestbath’s Approach to Scaling Problem-Solving Capability

Building a Problem-Solving Culture: Insights from Barton Malow’s Lean University

Related books

A3 Getting Started Guide

by Lean Enterprise Institute

The Power of Process – A Story of Innovative Lean Process Development

by Eric Ethington and Matt Zayko

Related events

April 16, 2024 | Coach-Led Online Course

Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata

June 10, 2024 | Coach-Led Online Course

Managing to Learn

Explore topics.

Subscribe to get the very best of lean thinking delivered right to your inbox

Privacy overview.

How to Improve the Problem-Solving Capacity of Your Team

by Heather Redding | Oct 18, 2019 | Leadership Development | 0 comments

Here is a great article by Heather Redding on how to improve the the problem-solving capacity of your team. She shares some great insights into this process. ~ Deseri Garcia

If you want your business to succeed, you need to lead from the front.

But leading from the front doesn’t mean doing everything.

It means setting an example and setting the pace for how your employees should respond to a variety of different situations.

Almost a century ago, Henry Ford invented the assembly line – a system that created a more efficient manufacturing methodology by assigning simple tasks to individual people.

But that doesn’t mean that your staff are all expendable cogs capable of just one goal.

Instilling your employees with problem-solving skills can create a versatile and more smoothly running work environment, and we’re here to show you how you can achieve that level of synchronicity.

Evaluate Your Existing Management Techniques

The unfortunate consequence of our modern management techniques means that employees often don’t have the skills to take initiative with a problem, and they often feel like they aren’t given the leverage to do so.

It’s easy to fall into a system of micromanagement , and many managers and owners aren’t even aware of how oppressive they are with their management styles.

Training your employees to be more self-sufficient is important, but we suggest you start by identifying any weaknesses in your own style.

Employees who are over-managed are going to feel less initiative to take the lead when they see a problem and will instead rely on the chain of command to resolve it.

Oftentimes, that will lead to inefficiencies.

That’s why it’s important to recognize when your management style may be too constricted.

Whether it’s an issue of micromanagement from an owner level or unnecessarily strict division of labor, making sure that your staff has the leverage to work with some degree of agency is important.

Be Clear and Concise

One of the biggest issues with problem-solving is creating too narrow a channel for your employees, but encouraging a system that’s too broad can be just as problematic.

After all, you don’t want your staff members to spend hours researching a problem that they don’t have a solution to when they could instead just call in the help of a more qualified department.

That’s why it’s important to create more structured parameters for each of your teams.

Problem-solving doesn’t always mean solving an issue yourself . It can instead mean recommending the issue to the person best equipped to resolve it.

If everyone knows the specializations of different departments, it will make them more confident in directing issues outside of their purview to people who can address it in a shorter time.

And that goes both ways.

Be Honest in Your Approach

What you say and what you do should be properly aligned.

Problem-solving means making mistakes, and if you want staff that’s willing to get creative , that means recognizing that sometimes they’re going to stumble and fail.

Encouraging creative approaches to problem-solving is a great thing, but you have to back that up with trust in your employees.

A creative approach to an issue can ultimately lead to failure, even if it’s the best way to find a new methodology.

Don’t punish your employees for being creative and failing. Instead, encourage them to not just be creative but to learn from their failures and apply it to future issues.

Accept Feedback

Most businesses are Byzantine affairs.

Multiple departments are sorting through multiple issues, and it can be hard to understand the different struggles that result in different results if you aren’t paying close enough attention.

Employees who know how to resolve a computer management issue might reach out to IT anyways because they believe that’s the protocol, or they might be worried about being held accountable for any mistakes they might make.

That’s why it’s important to regularly check in with your staff in every department.

Take the time to pull your employees aside regularly and address the problems they faced and how they resolved them.

In some cases, you’ll have staff members who addressed similar issues in different ways and be able to objectively determine which strategy worked better.

In other situations, you won’t come to conclusive results.

In either case, it’s important to not assign winners and losers.

The act of experimentation benefits your company, and multiple acts of experimentation can help you zero in on the best approach.

Trial and error is often the only way to find the best way.

Don’t be afraid to determine new company policies on what works best , but don’t punish employees for taking a bold approach that doesn’t pay off.

Proximity is Not Equal to Value

If you’re working in an office environment, it can be easy to prioritize the people on-site, but it’s important to not neglect remote employees.

Hiring remote team members can give you access to people who have honed their technical skills due to the virtual nature of their work.

Growing trends in remote work enrich teams with more tech-savvy individuals who can pass their troubleshooting knowledge onto others and spread the problem-solving mindset through your organization.

Identify those remote employees who work best autonomous of other people, spot their expertise and be sure to use them when you need some specialized skills.

Remote employees can be easy to overlook, but the businesses of today are increasingly agile and you don’t necessarily need someone on-site to solve a common technical problem .

Simplicity is Key

It can be incredibly easy to make a problem more complicated than it needs to be, and that’s why it’s critical to make sure that your staff is guided by the principle of boiling an issue down to its basic concepts.

If there’s a major problem that a team is facing, be sure to sit everyone down. Find a manager who understands the issue and break it down into its most basic component parts, and then let your team contribute solutions until you find the one that’s the best fit.

Even if one employee is guiding the issue, chances are good that other staff members will have the experience and knowledge to hone the idea.

It’s important to recognize that perfect is the enemy of good here.

Finding a solution that resolves every issue may not be possible. What’s more important is finding the best solution available to you.

Your team will function better without your iron grip.

Identify the problem solvers you already have in your company , whether they’re in the office or working remotely, and introduce some guidelines on how to problem-solve.

Give time to everyone in the company to get used to problem-solving and help them along the way, and slowly remove your management from the equation.

Your operations will be more streamlined and your employees empowered and more efficient.

Free download: Building A Winning Team

Heather Redding

Heather Redding is a part-time assistant manager, solopreneur and writer based in Aurora, Illinois. She is also an avid reader and a tech enthusiast. When Heather is not working or writing, she enjoys her Kindle library and a hot coffee. Reach out to her on Twitter .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Einstein (Sao Paulo)

What are the implications of problem-solving capacity at Primary Health Care in older adult health?

Carolina aguiar sant’anna siqueri.

1 Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo SP , Brazil, Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Gabriel Apolinário Pereira

Giuliana tamie sumida, ana carolina cintra nunes mafra.

2 Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo SP , Brazil, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Daiana Bonfim

Letícia yamawaka de almeida, camila nascimento monteiro.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

To evaluate Primary Health Care attributes and analyze the association between the fulfilment of these attributes and problem-solving capacity of services for elderly patients.

A cross-sectional, observational, quantitative study. The Primary Care Assessment Tool, designed to assess Primary Health Care attributes, was employed to evaluate elderly users of Primary Care Units located in the south region of the city of São Paulo (SP).

Many attributes assessed at the reference services were considered as unsatisfactory by users. Overall scores were also below the cut-off point. “First contact access – use”, “longitudinality” and “coordination – information system” were the only attributes considered as satisfactory. Also, more than half (62.7%) of respondent patients reported having been referred to specialized services. A combined analysis of these three outcomes revealed users referred to other services had a significantly better perception of Primary Health Care attributes.

The study provides important insights on satisfaction of elderly individuals and the problem-solving capacity of health care services, especially for the study population. Findings reported emphasize the association between Primary Health Care attributes and the problem-solving capacity of health care services at this level.

INTRODUCTION

Population aging in the last few decades has greatly impacted several sectors of the Brazilian society, including health. To cope with the needs and demands of this growing population, the health care sector had to be adapted and reorganized. ( 1 ) Primary Health Care (PHC) plays a key role in this process, not only through the control of risk factors and management of chronic diseases, but also through the coordination of referrals to other services in the health care network. ( 2 )

Primary Health Care operates based on four core attributes. Measurable structural and procedural elements pertaining to these attributes are: first contact care, longitudinality, integrality and coordination, and three derivatives, namely family counseling (or centrality), community orientation and cultural competence. ( 3 )

Fulfilment of these attributes, associated to service outcomes, can be combined to determine the performance of this sector of the health system. ( 3 ) The Primary Care Assessment Tool (PCATool), designed and validated by the Ministry of Health, measures the presence and scope of these attributes, according to experiences and perception of users and health care professionals. ( 4 )

Other variables can also be used to examine the effectiveness and determine the performance of PHC, such as hospitalization rates due to conditions that can be resolved at the primary care level and mortality coefficients. ( 5 , 6 ) A more pragmatic approach is the examination of the fundamental premises of PHC: resolution of 85% of health complaints and coordination of referrals and counter-referrals of users in the system. ( 7 ) The rate of referral to other levels of care can therefore be used to estimate the problem-solving capacity of the first level of care.

Increasing prevalence of multimorbidity, primarily due to chronic conditions, in the elderly population worldwide implies higher demands for specialized care and poses a major challenge to health systems. ( 8 - 10 )

Studies have shown that integrality and accessibility are the most significant attributes for prevention actions and attention to vulnerabilities in elderly populations. ( 11 , 12 ) Hence the need of a network of care. ( 13 ) Therefore, problem-solving capacity assessment according to referrals may also provide insights into network integration.

Another important attribute, particularly for elderly individuals with chronic conditions, is integrality. ( 14 ) The analysis of care provision in senior health settings must be based on the impact of these factors on the problem-solving capacity of health services, presuming the higher the PCATool score, the greater the problem-solving capacity of a given service.

Notwithstanding the great epidemiologic relevance of this population and respective health conditions in Brazil, little is known about the impacts of PHC attributes and their due implementation in particular settings on the final effectiveness of care.

Type of study

A cross-sectional, observational, quantitative study.

The sample comprised users of five PHC (UBS - Unidade Básica de Saúde ), located in the region of Supervisão Técnica de Saúde do Campo Limpo (STSCL), Campo Limpo and Vila Andrade administrative districts, in the south of São Paulo (SP). These units comprised 28 Family Health teams (ESF - Estratégia Saúde da Família ).

Teams were analyzed in a single model for sample calculation. Therefore, sample size was calculated first, then estimated per team. Individual attribute scores as well as PHC overall and essential scores were analyzed. To obtain a representative sample of each team, a sample size (n) of 12 users per team was calculated (n=336). This sample comprised 83 elderly individuals (aged over 60 years).

Data collection

Data were collected between July 2019 and January 2020. Users who were at their UBS of origin, whether waiting for consultation or as companions, were interviewed.

Following technical capacitation and training, the PCATool was administered by Medical and Nursing undergraduate students unrelated to the service. No specific sampling strategies were used. Participation was voluntary. Participants were individually approached and signed an informed consent form.

The global scenario brought about by the pandemics introduced several constraints in data collection. Had data been collected as planned ( i.e. , throughout 2020), a larger sample size would have been achieved.

Primary Health Care attributes: the data collection instrument Primary Care Assessment Tool-Brasil

The PCATool-Brasil (version for adults) was used. This instrument comprises the following variables: degree of affiliation to the health care service; first contact access - use; first contact access - accessibility; longitudinality; coordination – integration of care; coordination - information system (F), ( 4 ) comprising three items (F1, F2 and F3); integrality - services available (G); integrality - services provided (H); family counseling (I) and community orientation (J). ( 4 )

Perception of PHC attributes was measured using the PCATool and by specific and overall scores. Scores were presumed to reflect user evaluation of PHC; the higher the score, the better the evaluation. User evaluation of PHC attributes was used as a proxy for satisfaction: the better the evaluation, the higher the level of satisfaction with the service. Total score analysis was based on two values: (essential score) summed mean scores of essential attributes plus degree of affiliation, divided by the number of components and (overall score) summed mean scores of essential attribute and derivative components plus degree of affiliation, divided by the number of components. ( 4 )

Attributes scored higher than the cut-off (>6.6 points) were perceived as satisfactory. ( 15 )

Problem-solving capacity

Problem-solving capacity assessment was based on referral rates. In this analysis, referrals were defined as those reported by elderly individuals according to the following question: “In the last year, which professional of (the unit) referred you to a specialist?”.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics (absolute and relative frequencies). Means and standard deviations of continuous variables were also provided.

Sample size of 83 elderly individuals (54 referred to specialists and 28 not referred) is sufficient to detect differences between groups with medium effect size (h=0.65 and d=0.66 for comparison of proportions and means, respectively) with a level of significance of 5% and statistical power of 80%.

Associations between the medians of PHC attribute scores and referrals per individual were investigated using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Associations between morbidity and problem-solving capacity of PHC were investigated using the χ 2 test. Analyses were carried out using the R software. The level of significance was set at 5%.

This study is part of the project Regulação em Saúde: Fatores Relacionados à Resolutividade na Atenção Básica [Regulation on Health: Factors Related to Problem-solving Capacity in Primary Health Care], approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein (HIAE), # 3.935.181, CAAE: 06807019.2.0000.0071, and Municipal Health Department of São Paulo, # 3.263.871, CAAE: 06807019.2.3001.0086.

A total of 83 elderly individuals were interviewed. Of these, 69.9% were female. Mean age of the study population was 67.8 years (minimum and maximum age, 62.9 and 70.7 years, respectively). White and brown races were equally represented (42.2% each). As to socioeconomic profile, 54.2% had studied beyond the elementary level, 61.5% were retired, 54.9% received government benefits, and only 9.9% had health insurance ( Table 1 ).

Results expressed as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

In this sample, 42.5% of participants were regular users of services ( i.e. , registered users for more than 10 years) and 61.4% reported multimorbidity (median of two per person, 1;3).

Primary Care Assessment Tool Scores application ( Figure 1 ) revealed that first contact access - use was the highest rated attribute (median, 8.9). Other attributes perceived as satisfactory were longitudinality and coordination - information system (median of 7.1 and 7.8, respectively).

First contact access - accessibility and family counseling were the lowest rated attributes (median of 3.6 and 4.4, respectively). Other findings were as follows: coordination – integration of care (6.2), integrality - services available (6.0) and community orientation (6.1).

The degree of affiliation to the health care service (longitudinality attribute), was scored 6.7. Median essential and overall scores in this study were 6.2 (4.7-7.2) and 6.1 (4.6-7.0), respectively.

In this sample, 67.9% of elderly individuals reported not having difficulties to schedule a medical visit at their respective units as needed. As to integrality, 82% of respondents reported their prescriptions were reviewed and discussed by health care professionals. Out of 80 responses, 85% indicated health care professionals were aware of medications taken by patients, and 54.9% revealed lack of advice about fall prevention. With regard to longitudinality, 71.2% of respondents reported professionals were informed of their complete medical history.

The rate of referral of elderly individuals to specialists was 62.7%, indicating a problem-solving capacity of 37.3% ( Table 2 ). Medical specialists with the largest volumes of referrals were ophthalmology (21.13%), cardiology (14.7%) and orthopedics (14.7%).

Results expressed as median (interquartile range) or n (%).

The following scores differed significantly (p<0.05) between referred and not referred groups: first contact access – use, coordination – care integration, longitudinality, essential and overall scores. Scores were lower among not referred patients ( Figure 2 ).

Data analysis revealed that many attributes assessed at services of origin were perceived as unsatisfactory by service users. Overall scores were also below the cut-off. First contact – access, longitudinality and coordination – information system were the only attributes perceived as satisfactory. The fact that more than half (62.7%) of respondents reported having been referred to a specialty service shows that the perception of PHC attributes as satisfactory was significantly greater among referred users.

This study addressed an elderly population of health system users. These individuals are primarily PHC users and possibly rely on these services for medical care. ( 16 ) Also, given the substantial prevalence of multimorbidity in this age range and the significance of ongoing medical care for positive health outcomes, ( 17 ) longitudinality is a major concern. Finally, appropriate health data recording and use ensures easy and seamless exchange of information ( 18 ) between the different levels of the health care system. However, since PHC is an integrated system that relies on different attributes for appropriate functioning, ( 2 ) these attributes must be fulfilled to ensure health care quality.

First contact access – accessibility, and community orientation (derivative attribute) were the lowest rated attributes in this study. First contact access - accessibility scores suggest structural factors inherent to the health system may act as barriers to care, implying undisputable losses to the individuals and services expenses. ( 15 )

The impact of community orientation tends to be less significant, given the derivative nature of this attribute. ( 2 ) However, this property allows comprehensive assessment of health care deficiencies and flaws in a given region or collectivity ( 19 ) and is vital for appropriate health care provision.

To achieve a more satisfactory fulfillment of these attributes, the requirements of different populations may need to be individualized ( 19 ) and medical care tailored to community settings ( i.e. , local availability of resources for health promotion) or access constraints ( i.e. , identification and removal of physical barriers, e.g. ,).

Prates et al. ( 15 ) carried out a systematic review of publications addressing the assessment of attributes in different contexts and countries, and by different methods. Highest rating attributes in that review are consistent with findings of this study (first contact access – use (71.4%), longitudinality (64.0%) and coordination – care integration (54.5%).

In a different study with elderly individuals, ( 11 ) longitudinality was the highest rated attribute (mean score, 7.3; PCAT tool). Integrality was the second lowest rated (mean score, 4.7; PCAT tool). Likewise, integrality - services available, was the third lowest rated attribute in this study. Consistent results emphasize the robustness of the PCAT tool and support the reliability of assessments. ( 15 , 20 ) User dissatisfaction due to poor accessibility, care coordination and integrality, among other factors, has been emphasized in prior studies. ( 21 )

More than 80% of respondents reported that medical professionals are informed of and discuss about their prescriptions. This is an extremely relevant factor in the relation between user satisfaction and problem-solving capacity of health services for the study population. The issue of polypharmacy, and the vulnerability of elderly individuals to polypharmacy in particular, ( 22 ) highlight the implications of prescription revision for positive outcomes and health care quality in this population. Growing frailty and increased risk of falls in elderly individuals emphasize the significance of patient education in this regard. ( 23 ) The fact that a substantial number of respondents reported not having received guidance about fall prevention indicates an opportunity for improvement in the integrality attribute.

Analysis based on referral rates revealed a problem-solving capacity of 37.3%. This study involved elderly individuals with chronic diseases and multimorbidity, most of them suffering from more than two comorbidities, which implies more referrals. Of elderly individuals analyzed in National Health Survey (PNS - Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde ) those with more morbidities were also the ones who used health care services more often and attributed higher scores (6.1 in a 0-10 scale) to these services. ( 24 )

Combined analysis of attributes and problem-solving capacity revealed that patients referred to other services tended to rate their UBS of origin higher. Importantly, health professionals working at these units act as system gatekeepers. ( 25 ) Ideally, referrals should be a matter of continuity rather than replacement of PHC, to achieve the desired integrality. ( 26 ) However, referral increases the chances of meeting user needs of specialized, high complexity care.

Of notice, according to Costa et al. ( 26 ) services that fulfill their PHC attributes should be able to provide better care to users, with less need of referral and not otherwise, as shown in this study. Greater attention on the part of managers and team members is needed to offer more standardized care, with resultant benefits to users.

The cultural perspective of health care service use must also be accounted for. Specialty referral is the primary goal of many UBS users, whereas the primary level of care and its inherent problem-solving capacity are not duly appreciated. ( 27 ) Therefore, aside from structural changes, user expectations must be understood and respected for PHC consolidation.

The construction of a more robust PHC, with greater problem-solving capacity for this population, and aimed to deliver better health outcomes in chronic conditions, can be achieved through a more effective articulation of services in health care networks ( RAS - Redes de Atenção à Saúde ). ( 2 ) The identification and resolution of well-established lack of family and community medicine competencies required to detect and stratify risk factors, such as frailty, ( 28 , 29 ) can help to optimize care protocols for this population and prevent negative impacts and unfavorable outcomes.

This study has limitations, such as small sample size due to challenges in data collection.

Implications of results reported range from the need to improve the health care system and the PHC level to greater attention to users and their perception of health care. Finally, the fact that problem-solving capacity can be assessed in several ways and that referral rates may contain inconsistencies, must be emphasized.

The study provides important insights into the perception of elderly individuals and the problem-solving capacity of health care services, and is of relevance to the study population. Findings reported emphasize the association between Primary Health Care attributes and the problem-solving capacity of health care services at this level, and highlights areas for improvement (frailty, access, and network articulation).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (process 409134/2018-0) for financing support provided to carry out the study.

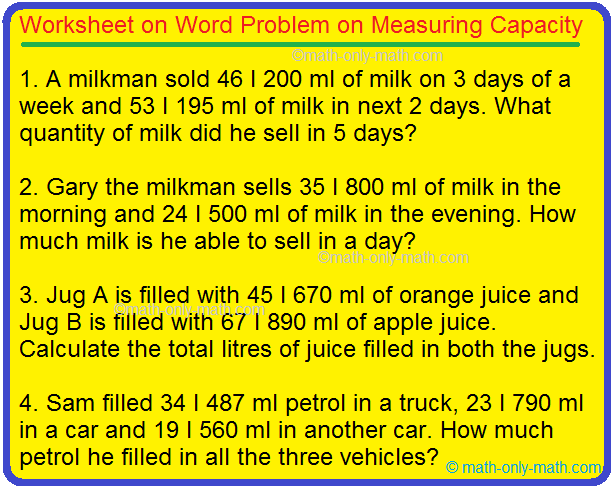

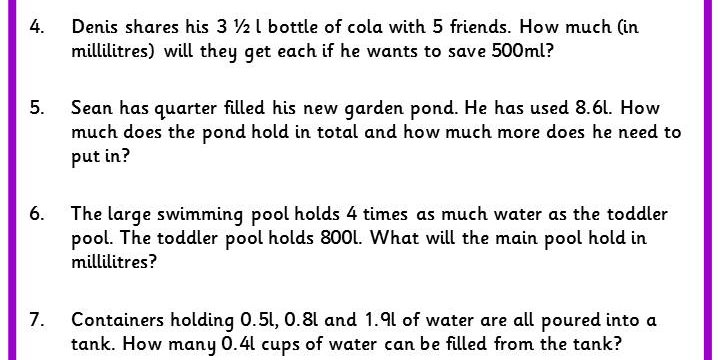

Worksheet on Word Problem on Measuring Capacity

Practice the questions given in the worksheet on word problem on measuring capacity (i.e. addition and subtraction). Addition and subtraction of word problems in liters and milliliters is done in the similar way as in the case of ordinary numbers.

Solve the following word problems on addition and subtraction of Capacity:

1. A milkman sold 46 l 200 ml of milk on 3 days of a week and 53 l 195 ml of milk in next 2 days. What quantity of milk did he sell in 5 days?

2. Gary the milkman sells 35 l 800 ml of milk in the morning and 24 l 500 ml of milk in the evening. How much milk is he able to sell in a day?

3. Sara bought 500 ml of mustard oil, 250 ml of coconut oil and 2 l of refined oil. What is the total quantity of the 3 oils together?

4. Ruby bought a 5 l Sunflower oil can from the market on Tuesday. By Friday only 2 l 440 ml of oil was left in it. How much quantity of oil was consumed in 3 days?

5. Alex consumed 15 l of water in 2 days and 27 litres of water in the rest of the days of the week. How much water was consumed in a week by him?

6. Gary the milkman delivers 1 l 250 ml of milk everyday at Mr. Jones house. What quantity of milk is delivered by the milkman to Mr. Jones house in a week?

7. Mary purchased 500 ml bottle of Pepsi, 300 ml can of Frooti and 2 litres of Limca. What quantity of cold drinks did Mary purchases altogether?

8. Shelly has 2 l of oil. She wants to pour it equally into 250 ml bottles. How many bottles is she able to fill with the oil?

9. Harry had 3 buckets of different capacity which could hold 9 l 257 ml, 12 l 420 ml and 30 l 100 ml of water. How much water could be stored in all?

10. Petrol costs $ 75 per liter. Tina gets her car tank filled with 46 liters of petrol. How much amount does she pays at the petrol pump.

11. There is 478 liters and 360 milliliters of water in the tank. 239 liters and 125 milliliters of water is consumed. How much water is left in the tank?

12. A swimming pool with a capacity of 200000 l. If there is 115730 l of water in the pool, how much more water can be put in the pool?

13. The capacity of the milk boiler is 2 l 500 ml of milk. If 1 l 200 ml of milk is put into the vessel then how much more quantity of milk can be filled in the vessel?

14. A cow gives 22 l 350 ml of milk each day. If the milk man has 20 cows then:

(i) How much milk will he get in a day?

(ii) If all the milk is filled in the bottles of capacity 500 ml, how many bottles will be required?

15. An oil can holds 5 l of oil. How much oil is left in the can if 2 l 750 ml of oil is used?

16. Neil has 2 cars, one with a capacity of 33 l 770 ml and other with a capacity of 42 l 550 ml. If petrol tanks of both the cars are empty, how much petrol can he fill in the tanks?

17. 35 l 450 ml of petrol was filled in the car and 29 l 561 ml of petrol was used in a month. How much petrol is left in the car?

18. Adrian has 44 l of liquid soap and wants to fill it in 25 Cans of capacity 550 ml each.

(i) Will he be able to fill all the Cans completely?

(ii) How much quantity of liquid soap will be left out?

19. In 1 ½ liter of cold drink bottle only 320 ml of cold drink is left. How much cold drink is consumed?

20. A water purifier cleans 100 l 150 ml of water each day. How much water will be cleaned by the cleaner in a week?

21. The consumption of diesel in a truck. A on one day is 102 l 208 ml and the consumption of truck B is 105 l 196 ml. Whose consumption is less and by how much?

22. Clara made 20 l 500 ml of lime squash on Saturday and 18 l 255 ml of lime squash on Sunday. On which day lime squash was prepared in more quantity and by how much?

23. Jug A is filled with 45 l 670 ml of orange juice and Jug B is filled with 67 l 890 ml of apple juice. Calculate the total litres of juice filled in both the jugs.

24. Sam filled 34 l 487 ml petrol in a truck, 23 l 790 ml in a car and 19 l 560 ml in another car. How much petrol he filled in all the three vehicles?

25. An oil tank has 162 l 345 ml oil. 78l 589 ml oil is removed from the tank. How much oil is left in the tank now?

26. There are two water tanks on a terrace of a building. Tank A has the capacity to hold 57 l 900 ml and tank B can hold 63 l 500 ml.

(i)Which tank can hold more and how much more it can hold?

(ii) What is the total capacity of both the tanks?

27. Factory A produces 146 l of juices and factory B produces 234l 467 ml of juices. Calculate the total litres of juices produced in both the factories?

Answers for the worksheet on word problem on measuring capacity (i.e. addition and subtraction in liters and milliliters) are given below.

1. 99 l 395 ml

2. 60 l 300 ml

3. 2 l 750 ml

4. 2 l 560 ml

6. 8 l 750 ml

7. 2 l 800 ml

9. 51 l 777 ml

11. 239 l 235 ml

12. 84270 l

13. 1 l 300 ml

14. (i) 447 l

15. 2 l 250 ml

16. 76 l 320 ml

17. 5 l 889 ml

18. (i) Yes

(ii) 30 l 250 ml

19. 1 l 180 ml

20. 701 l 50 ml

21. Truck A by 2 l 988 ml

22. Saturday by 2 l 245 ml

23. 113 ℓ 560 mℓ

24. 77 ℓ 837 mℓ

25. 83 ℓ 756 mℓ

26. (i) Tank B, 5 ℓ 600 mℓ

(ii) 121 ℓ 400 mℓ

27. 380 ℓ 467 mℓ

Standard Unit of Capacity

Conversion of Standard Unit of Capacity

Addition of Capacity

Subtraction of Capacity

Addition and Subtraction of Measuring Capacity

3rd Grade Math Worksheets

3rd Grade Math Lessons

From Worksheet on Word Problem on Measuring Capacity to HOME PAGE

New! Comments

Didn't find what you were looking for? Or want to know more information about Math Only Math . Use this Google Search to find what you need.

- Preschool Activities

- Kindergarten Math

- 1st Grade Math

- 2nd Grade Math

- 3rd Grade Math

- 4th Grade Math

- 5th Grade Math

- 6th Grade Math

- 7th Grade Math

- 8th Grade Math

- 9th Grade Math

- 10th Grade Math

- 11 & 12 Grade Math

- Concepts of Sets

- Probability

- Boolean Algebra

- Math Coloring Pages

- Multiplication Table

- Cool Maths Games

- Math Flash Cards

- Online Math Quiz

- Math Puzzles

- Binary System

- Math Dictionary

- Conversion Chart

- Homework Sheets

- Math Problem Ans

- Free Math Answers

- Printable Math Sheet

- Funny Math Answers

- Employment Test

- Math Patterns

- Link Partners

- Privacy Policy

Recent Articles

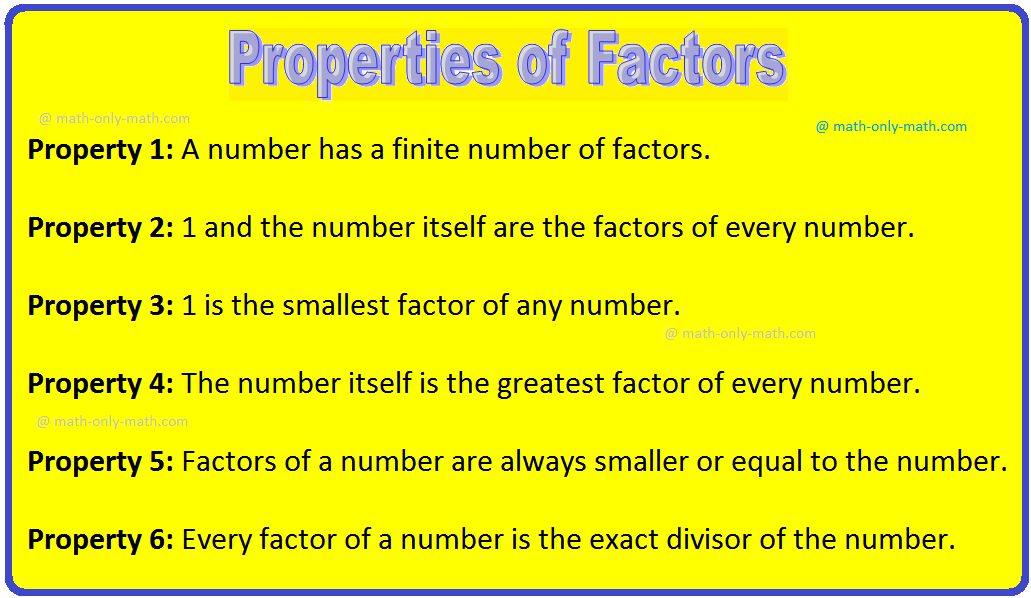

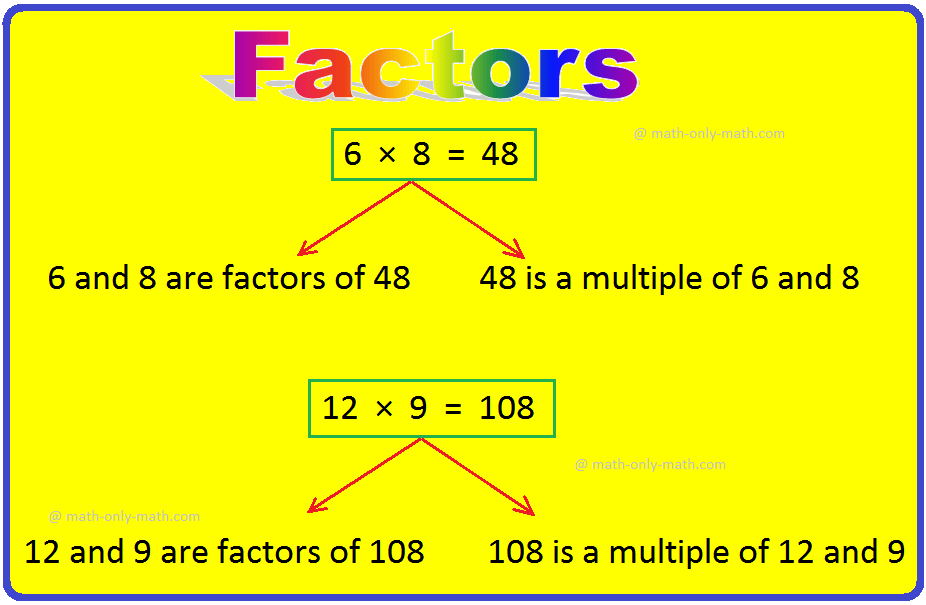

Properties of Factors | 1 is the Smallest Factor|At Least Two Factors

Apr 11, 24 01:20 PM

Factors | Understand the Factors of the Product | Concept of Factors

Apr 11, 24 09:46 AM

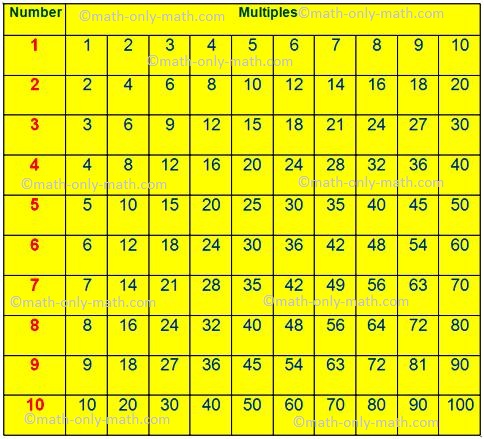

Multiples | Multiples of a Number |Common Multiple|First Ten Multiples

Apr 10, 24 04:34 PM

Properties of Multiples | With Examples | Multiple of each Factor

Apr 10, 24 02:58 PM

Dividing 3-Digit by 1-Digit Number | Long Division |Worksheet Answer

Apr 09, 24 02:58 PM

© and ™ math-only-math.com. All Rights Reserved. 2010 - 2024.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

- The Number System and Place Value

- Calculations and Numerical Methods

- Fractions, Decimals, Percentages, Ratio and Proportion

- Properties of Numbers

- Patterns, Sequences and Structure

- Algebraic expressions, equations and formulae

- Coordinates, Functions and Graphs

Geometry and measure

- Angles, Polygons, and Geometrical Proof

- 3D Geometry, Shape and Space

- Measuring and calculating with units

- Transformations and constructions

- Pythagoras and Trigonometry

- Vectors and Matrices

Probability and statistics

- Handling, Processing and Representing Data

- Probability

Working mathematically

- Thinking mathematically

- Mathematical mindsets

- Cross-curricular contexts

- Physical and digital manipulatives

For younger learners

- Early Years Foundation Stage

Advanced mathematics

- Decision Mathematics and Combinatorics

- Advanced Probability and Statistics

Volume and Capacity KS2

This collection is one of our Primary Curriculum collections - tasks that are grouped by topic.

Next Size Up

The challenge for you is to make a string of six (or more!) graded cubes.

Pouring Problem

What do you think is going to happen in this video clip? Are you surprised?

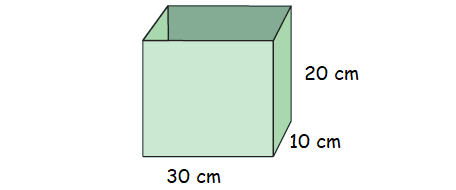

VOLUME AND CAPACITY WORD PROBLEMS

The units for capacity and the units for volume are closely related.

1 mL of fluid will fill a cube 1 cm x 1 cm x 1 cm.

1 cm 3 has capacity 1 mL

1 L of fluid will fill a cube 10 cm x 10 cm x 10 cm.

1000 cm 3 has capacity 1 L

1 kL of fluid will fill a cube 1 m x 1 m x 1 m.

1 m 3 has capacity 1 kL.

1 cm 3 = 1 mL

1000 cm 3 = 1 L

1 m 3 = 1 KL

Example 1 :

Calculate the capacity of the container:

Volume of the container = 30 x 10 x 20 cm 3

= 6000 cm 3

1000 ml = 1 L

= (6000/1000) L

So, the capacity of the container is 6 L.

Example 2 :

Find the capacity in liters of a fish tank 2 m by 1 m and 50 cm.

Volume of tank = l x w x h

Substitute l = 2, w = 1 and h = 50 cm or 0.5 m.

= 2 x 1 x 0.50

So, capacity of the tank is 1 KL.

Example 3 :

A rectangular petrol tank has dimensions 50 cm by 40 cm by 25 cm. How many liters of petrol are needed to fill it?

Volume of rectangular tank = l x w x h.

Substitute l = 50, w = 40 and h = 25.

= 50 x 40 x 25

= 50000 cm 3

= 50000/1000

So, the capacity of the petrol tank is 50 L.

Example 4 :

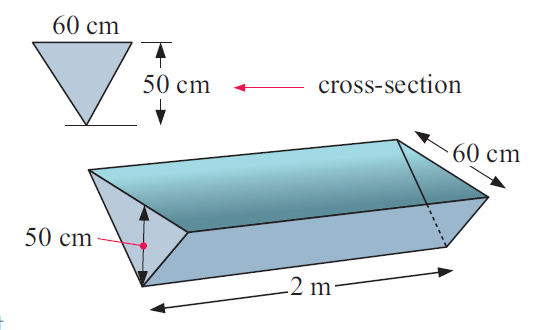

A water trough has triangular cross-section as shown. Its length is 2 m.

a) the area of the triangle in cm 2

b) the volume of space in the trough in cm 3

c) the capacity of the trough in :

i) litres ii) kilolitres.

Area of triangle :

= (1/2) ⋅ base ⋅ height

Base = 60 cm and height = 50 cm

= (1/2) ⋅ 60 ⋅ 50

= 1500 cm 3

Volume of space :

= (1/2) ⋅ Base area x height

= (1/2) ⋅ 1500 ⋅ 200

= 300000 cm 3

= 300000/1000

= 300 Liter

So, capacity of triangular prism is 300 liter.

1m 3 = 1 KL

1000 ml = 1 kl

So, capacity of triangular prism is 0.3 kl.

Example 5 :

Find the capacity in megaliters of a reservoir with a surface area of 1 hectare and an average depth of 2.5 meters.

1 hectare = 10000 m 2

Volume = Surface area x height

= 10000 x 2.5

= 25000 m 3

1 m 3 = 1 KL

Capacity = 25000/1000 ML

So, the capacity is 25 ML.

Example 6 :

A kidney-shaped swimming pool has surface area 15 m 2 and a constant depth of 2 meters. Find the capacity of the pool in kiloliters.

Surface area = 15 m 2 and height = 2 m

So, the capacity is 30 KL .

Example 7 :

A lake has an average depth of 6 m and a surface area of 35 ha. Find its capacity in megaliters .

35 hectare = 350000 m 2

Height = 6 m

= 350000 x 6

= 2100000 m 3

= 2100000 Kl

1 ML = 1000 KL

= 2100000/1000 ML

So, the capacity of the tank is 2100 ML.

Kindly mail your feedback to [email protected]

We always appreciate your feedback.

© All rights reserved. onlinemath4all.com

- Sat Math Practice

- SAT Math Worksheets

- PEMDAS Rule

- BODMAS rule

- GEMDAS Order of Operations

- Math Calculators

- Transformations of Functions

- Order of rotational symmetry

- Lines of symmetry

- Compound Angles

- Quantitative Aptitude Tricks

- Trigonometric ratio table

- Word Problems

- Times Table Shortcuts

- 10th CBSE solution

- PSAT Math Preparation

- Privacy Policy

- Laws of Exponents

Recent Articles

Sinusoidal Function

Apr 10, 24 11:49 PM

How to Find a Limit Using a Table

Apr 09, 24 08:44 PM

Evaluating Logarithms Worksheet

Apr 09, 24 09:30 AM

- Home Learning

- Free Resources

- New Resources

- Free resources

- New resources

- Filter resources

- Childrens mental health

- Easter resources

Internet Explorer is out of date!

For greater security and performance, please consider updating to one of the following free browsers

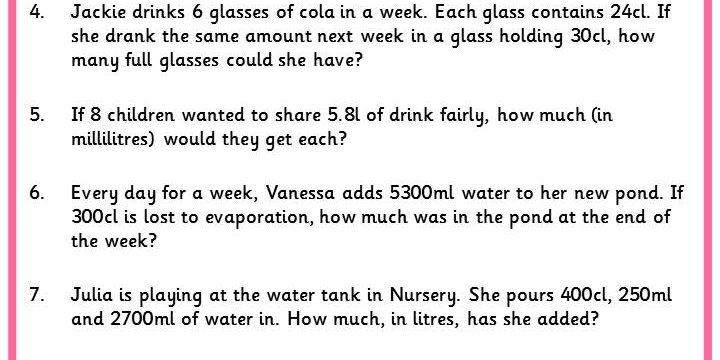

Capacity Problems

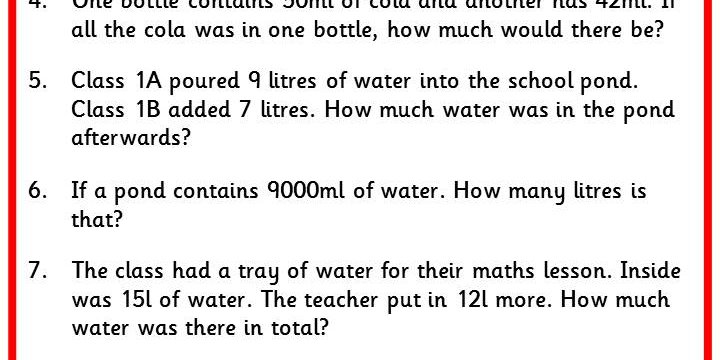

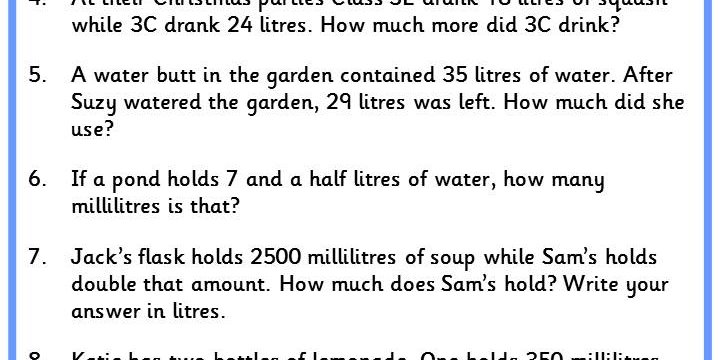

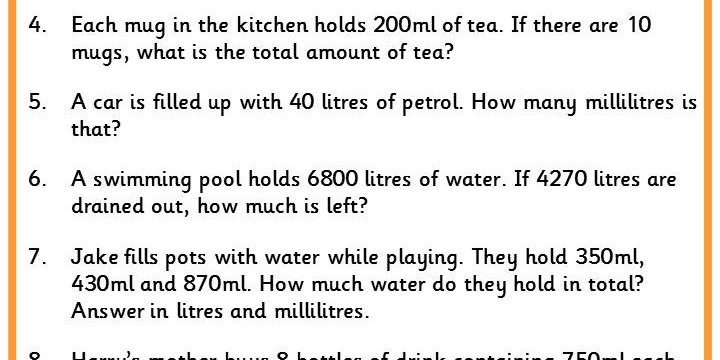

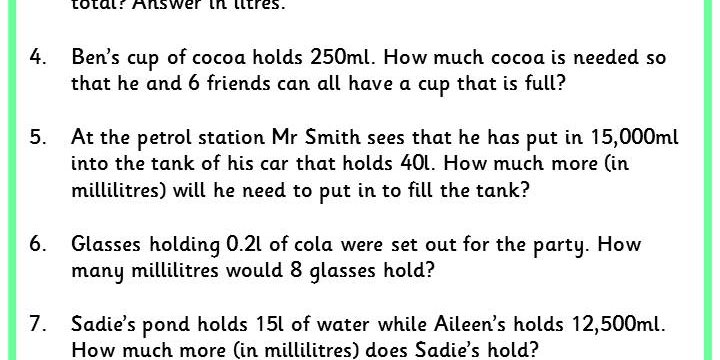

National Curriculum Objective Mathematics Y3: (3M9b) Measure, compare, add and subtract: lengths (m/cm/mm); mass (kg/g); volume/capacity (l/ml) Mathematics Y5: (5M5) Convert between different units of metric measure (for example, kilometre and metre; centimetre and metre; centimetre and millimetre; gram and kilogram; litre and millilitre) Mathematics Y5: (5M9a) Use all four operations to solve problems involving measure [for example, length, mass, volume, money] using decimal notation, including scaling Mathematics Y6: (6M9) Solve problems involving the calculation and conversion of units of measure, using decimal notation up to three decimal places where appropriate Mathematics Y6: (6M5) Use, read, write and convert between standard units, converting measurements of length, mass, volume and time from a smaller unit of measure to a larger unit, and vice versa, using decimal notation to up to three decimal places

Differentiation:

Beginner Adding only or simple conversion with 2 digit numbers (litres and millilitres). Aimed at Year 3 Developing.

Easy Adding, subtracting or simple conversion with 2 or 3 digit numbers (litres and millilitres). Aimed at Year 3 Secure.

Tricky Adding, subtracting, multiplying or simple conversion with any integer (litres and millilitres). Aimed at Year 5 Developing.

Expert Adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing or decimal conversion with any integer (litres and millilitres). Aimed at Year 5 Secure/Year 6 Emerging.

Brainbox Two-step problems with adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing or decimal conversion with any integer (litres and millilitres). Aimed at Year 6 Developing.

Genius Multi-step problems with adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing or decimal conversion with any integer (litres, millilitres and centilitres). Aimed at Year 6 Secure.

Worksheets include answers.

Capacity Problems - Beginner (Worksheet)

Login to download

Not a member? Sign up here.

Capacity Problems - Easy (Worksheet)

Capacity Problems - Tricky (Worksheet)

Capacity Problems - Expert (Worksheet)

Capacity Problems - Brainbox (Worksheet)

Capacity Problems - Genius (Worksheet)

This resource is available to download with a Premium subscription.

Our Mission

To help our customers achieve a life/work balance and understand their differing needs by providing resources of outstanding quality and choice alongside excellent customer support..

Yes, I want that!

Keep up to date by liking our Facebook page:

Membership login, stay in touch.

01422 419608

[email protected]

Interested in getting weekly updates from us? Then sign up to our newsletter here!

Information

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

Copyright: Classroom Secrets 2024

Company number: 8401067

VAT number: 248 8245 74

- Terms & Conditions

Designed by Classroom Secrets

Pave the Way for Self-regulation and Problem-solving With Social-emotional Learning

Posted: April 3, 2024

Problem-solving is a social-emotional learning (SEL) skill children need for lifelong success. Effective problem-solving skills support children's ability to self-regulate, focus on tasks, think flexibly and creatively, work with others, and generate multiple ways to solve problems. When young children develop and build these skills, it positively impacts their interactions with others, grows their capacity to manage challenges, and boosts a sense of competence.

A group of school-age children are stacking plastic blocks with an educator.

The foundation for effective social problem-solving is grounded in self-regulation, or the ability to regulate emotions when interacting with others. It is easier to focus on one's feelings and the feelings and perspectives of others and to work cooperatively toward solutions when a child can self-regulate and calm down. Children develop self-regulation skills over time, with practice and with adult guidance. Equally important is how an adult models emotion regulation and co-regulation.

"Caregivers play a key role in cultivating the development of emotion regulation through co-regulation, or the processes by which they provide external support or scaffolding as children navigate their emotional experiences" (Paley & Hajal, 2022, p. 1).

When adults model calm and self-regulated approaches to problem-solving, it shows children how to approach problems constructively. For example, an educator says, "I'm going to take a breath and calm down so I can think better." This model helps children see and hear a strategy to support self-regulation.

Problem-solving skills help children resolve conflicts and interact with others as partners and collaborators. Developing problem-solving skills helps children learn and grow empathy for others, stand up for themselves, and build resilience and competence to work through challenges in their world.

Eight strategies to support problem-solving

- Teach about emotions and use feeling words throughout the day. When children have more words to express themselves and their feelings, it is easier to address and talk about challenges when they arise.

- Recognize and acknowledge children's feelings throughout the day. For example, when children enter the classroom during circle time, mealtime, and outside time, ask them how they feel. Always acknowledge children's feelings, both comfortable and uncomfortable, to support an understanding that all feelings are OK to experience.

- Differentiate between feelings and behaviors. By differentiating feelings from behaviors, educators contribute to children’s understanding that all feelings are OK, but not all behaviors are OK. For example, an educator says, "It looks like you may be feeling mad because you want the red blocks, and Nila is playing with them. It's OK to feel mad but not OK to knock over your friend’s blocks."

- Support children's efforts to calm down. When children are self-regulated, they can think more clearly. For example, practice taking a breath with children as a self-regulation technique during calm moments. Then, when challenges arise, children have a strategy they have practiced many times and can use to calm down before problem-solving begins.

- Encourage children's efforts to voice the problem and their feelings after they are calm. For example, when a challenge arises, encourage children to use the phrase, "The problem is_______, and I feel______." This process sets the stage to begin problem-solving.

- Acknowledge children's efforts to think about varied ways to solve problems. For example, an educator says, "It looks like you and Nila are trying to work out how to share the blocks. What do you think might work so you can both play with them? Do you have some other ideas about how you could share?"

- Champion children's efforts as they problem-solve. For example, "You and Nila thought about two ways you could share. One way is to divide the red blocks so you can each build, and the other is to build a tower together. Great thinking, friends!"

- Create opportunities for activities and play that offer problem-solving practice. For example, when children play together in the block area, it provides opportunities to negotiate plans for play and role-play, build perspective, talk about feelings, and share. The skills children learn during play, along with adult support, enhance children’s ability to solve more complex and challenging social problems and conflicts when they occur in and out of the early learning setting.

References:

Paley, B., & Hajal, N. J. (2022). Conceptualizing emotion regulation and coregulation as family-level phenomena. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review , 25 (1), 19-43.

Social Media

- X (Twitter)

- Degrees & Programs

- College Directory

Information for

- Faculty & Staff

- Visitors & Public

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Do You Understand the Problem You’re Trying to Solve?

To solve tough problems at work, first ask these questions.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem without taking time to really understand the dilemma we face, according to Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg , an expert in innovation and the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for just one root cause can be misleading.

Key episode topics include: leadership, decision making and problem solving, power and influence, business management.

HBR On Leadership curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock the best in those around you. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the original HBR IdeaCast episode: The Secret to Better Problem Solving (2016)

- Find more episodes of HBR IdeaCast

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR on Leadership , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock the best in those around you.

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But even the most experienced among us can fall into the trap of solving the wrong problem.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg says that all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem – without taking time to really understand what we’re facing.

He’s an expert in innovation, and he’s the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems, by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for one root cause can be misleading. And you’ll learn how to use experimentation and rapid prototyping as problem-solving tools.

This episode originally aired on HBR IdeaCast in December 2016. Here it is.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Welcome to the HBR IdeaCast from Harvard Business Review. I’m Sarah Green Carmichael.

Problem solving is popular. People put it on their resumes. Managers believe they excel at it. Companies count it as a key proficiency. We solve customers’ problems.

The problem is we often solve the wrong problems. Albert Einstein and Peter Drucker alike have discussed the difficulty of effective diagnosis. There are great frameworks for getting teams to attack true problems, but they’re often hard to do daily and on the fly. That’s where our guest comes in.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg is a consultant who helps companies and managers reframe their problems so they can come up with an effective solution faster. He asks the question “Are You Solving The Right Problems?” in the January-February 2017 issue of Harvard Business Review. Thomas, thank you so much for coming on the HBR IdeaCast .

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Thanks for inviting me.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I thought maybe we could start by talking about the problem of talking about problem reframing. What is that exactly?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Basically, when people face a problem, they tend to jump into solution mode to rapidly, and very often that means that they don’t really understand, necessarily, the problem they’re trying to solve. And so, reframing is really a– at heart, it’s a method that helps you avoid that by taking a second to go in and ask two questions, basically saying, first of all, wait. What is the problem we’re trying to solve? And then crucially asking, is there a different way to think about what the problem actually is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I feel like so often when this comes up in meetings, you know, someone says that, and maybe they throw out the Einstein quote about you spend an hour of problem solving, you spend 55 minutes to find the problem. And then everyone else in the room kind of gets irritated. So, maybe just give us an example of maybe how this would work in practice in a way that would not, sort of, set people’s teeth on edge, like oh, here Sarah goes again, reframing the whole problem instead of just solving it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I mean, you’re bringing up something that’s, I think is crucial, which is to create legitimacy for the method. So, one of the reasons why I put out the article is to give people a tool to say actually, this thing is still important, and we need to do it. But I think the really critical thing in order to make this work in a meeting is actually to learn how to do it fast, because if you have the idea that you need to spend 30 minutes in a meeting delving deeply into the problem, I mean, that’s going to be uphill for most problems. So, the critical thing here is really to try to make it a practice you can implement very, very rapidly.

There’s an example that I would suggest memorizing. This is the example that I use to explain very rapidly what it is. And it’s basically, I call it the slow elevator problem. You imagine that you are the owner of an office building, and that your tenants are complaining that the elevator’s slow.

Now, if you take that problem framing for granted, you’re going to start thinking creatively around how do we make the elevator faster. Do we install a new motor? Do we have to buy a new lift somewhere?

The thing is, though, if you ask people who actually work with facilities management, well, they’re going to have a different solution for you, which is put up a mirror next to the elevator. That’s what happens is, of course, that people go oh, I’m busy. I’m busy. I’m– oh, a mirror. Oh, that’s beautiful.

And then they forget time. What’s interesting about that example is that the idea with a mirror is actually a solution to a different problem than the one you first proposed. And so, the whole idea here is once you get good at using reframing, you can quickly identify other aspects of the problem that might be much better to try to solve than the original one you found. It’s not necessarily that the first one is wrong. It’s just that there might be better problems out there to attack that we can, means we can do things much faster, cheaper, or better.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, in that example, I can understand how A, it’s probably expensive to make the elevator faster, so it’s much cheaper just to put up a mirror. And B, maybe the real problem people are actually feeling, even though they’re not articulating it right, is like, I hate waiting for the elevator. But if you let them sort of fix their hair or check their teeth, they’re suddenly distracted and don’t notice.

But if you have, this is sort of a pedestrian example, but say you have a roommate or a spouse who doesn’t clean up the kitchen. Facing that problem and not having your elegant solution already there to highlight the contrast between the perceived problem and the real problem, how would you take a problem like that and attack it using this method so that you can see what some of the other options might be?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right. So, I mean, let’s say it’s you who have that problem. I would go in and say, first of all, what would you say the problem is? Like, if you were to describe your view of the problem, what would that be?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I hate cleaning the kitchen, and I want someone else to clean it up.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: OK. So, my first observation, you know, that somebody else might not necessarily be your spouse. So, already there, there’s an inbuilt assumption in your question around oh, it has to be my husband who does the cleaning. So, it might actually be worth, already there to say, is that really the only problem you have? That you hate cleaning the kitchen, and you want to avoid it? Or might there be something around, as well, getting a better relationship in terms of how you solve problems in general or establishing a better way to handle small problems when dealing with your spouse?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Or maybe, now that I’m thinking that, maybe the problem is that you just can’t find the stuff in the kitchen when you need to find it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right, and so that’s an example of a reframing, that actually why is it a problem that the kitchen is not clean? Is it only because you hate the act of cleaning, or does it actually mean that it just takes you a lot longer and gets a lot messier to actually use the kitchen, which is a different problem. The way you describe this problem now, is there anything that’s missing from that description?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That is a really good question.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Other, basically asking other factors that we are not talking about right now, and I say those because people tend to, when given a problem, they tend to delve deeper into the detail. What often is missing is actually an element outside of the initial description of the problem that might be really relevant to what’s going on. Like, why does the kitchen get messy in the first place? Is it something about the way you use it or your cooking habits? Is it because the neighbor’s kids, kind of, use it all the time?

There might, very often, there might be issues that you’re not really thinking about when you first describe the problem that actually has a big effect on it.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I think at this point it would be helpful to maybe get another business example, and I’m wondering if you could tell us the story of the dog adoption problem.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Yeah. This is a big problem in the US. If you work in the shelter industry, basically because dogs are so popular, more than 3 million dogs every year enter a shelter, and currently only about half of those actually find a new home and get adopted. And so, this is a problem that has persisted. It’s been, like, a structural problem for decades in this space. In the last three years, where people found new ways to address it.

So a woman called Lori Weise who runs a rescue organization in South LA, and she actually went in and challenged the very idea of what we were trying to do. She said, no, no. The problem we’re trying to solve is not about how to get more people to adopt dogs. It is about keeping the dogs with their first family so they never enter the shelter system in the first place.

In 2013, she started what’s called a Shelter Intervention Program that basically works like this. If a family comes and wants to hand over their dog, these are called owner surrenders. It’s about 30% of all dogs that come into a shelter. All they would do is go up and ask, if you could, would you like to keep your animal? And if they said yes, they would try to fix whatever helped them fix the problem, but that made them turn over this.

And sometimes that might be that they moved into a new building. The landlord required a deposit, and they simply didn’t have the money to put down a deposit. Or the dog might need a $10 rabies shot, but they didn’t know how to get access to a vet.

And so, by instigating that program, just in the first year, she took her, basically the amount of dollars they spent per animal they helped went from something like $85 down to around $60. Just an immediate impact, and her program now is being rolled out, is being supported by the ASPCA, which is one of the big animal welfare stations, and it’s being rolled out to various other places.

And I think what really struck me with that example was this was not dependent on having the internet. This was not, oh, we needed to have everybody mobile before we could come up with this. This, conceivably, we could have done 20 years ago. Only, it only happened when somebody, like in this case Lori, went in and actually rethought what the problem they were trying to solve was in the first place.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, what I also think is so interesting about that example is that when you talk about it, it doesn’t sound like the kind of thing that would have been thought of through other kinds of problem solving methods. There wasn’t necessarily an After Action Review or a 5 Whys exercise or a Six Sigma type intervention. I don’t want to throw those other methods under the bus, but how can you get such powerful results with such a very simple way of thinking about something?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That was something that struck me as well. This, in a way, reframing and the idea of the problem diagnosis is important is something we’ve known for a long, long time. And we’ve actually have built some tools to help out. If you worked with us professionally, you are familiar with, like, Six Sigma, TRIZ, and so on. You mentioned 5 Whys. A root cause analysis is another one that a lot of people are familiar with.

Those are our good tools, and they’re definitely better than nothing. But what I notice when I work with the companies applying those was those tools tend to make you dig deeper into the first understanding of the problem we have. If it’s the elevator example, people start asking, well, is that the cable strength, or is the capacity of the elevator? That they kind of get caught by the details.

That, in a way, is a bad way to work on problems because it really assumes that there’s like a, you can almost hear it, a root cause. That you have to dig down and find the one true problem, and everything else was just symptoms. That’s a bad way to think about problems because problems tend to be multicausal.

There tend to be lots of causes or levers you can potentially press to address a problem. And if you think there’s only one, if that’s the right problem, that’s actually a dangerous way. And so I think that’s why, that this is a method I’ve worked with over the last five years, trying to basically refine how to make people better at this, and the key tends to be this thing about shifting out and saying, is there a totally different way of thinking about the problem versus getting too caught up in the mechanistic details of what happens.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: What about experimentation? Because that’s another method that’s become really popular with the rise of Lean Startup and lots of other innovation methodologies. Why wouldn’t it have worked to, say, experiment with many different types of fixing the dog adoption problem, and then just pick the one that works the best?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: You could say in the dog space, that’s what’s been going on. I mean, there is, in this industry and a lot of, it’s largely volunteer driven. People have experimented, and they found different ways of trying to cope. And that has definitely made the problem better. So, I wouldn’t say that experimentation is bad, quite the contrary. Rapid prototyping, quickly putting something out into the world and learning from it, that’s a fantastic way to learn more and to move forward.

My point is, though, that I feel we’ve come to rely too much on that. There’s like, if you look at the start up space, the wisdom is now just to put something quickly into the market, and then if it doesn’t work, pivot and just do more stuff. What reframing really is, I think of it as the cognitive counterpoint to prototyping. So, this is really a way of seeing very quickly, like not just working on the solution, but also working on our understanding of the problem and trying to see is there a different way to think about that.

If you only stick with experimentation, again, you tend to sometimes stay too much in the same space trying minute variations of something instead of taking a step back and saying, wait a minute. What is this telling us about what the real issue is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, to go back to something that we touched on earlier, when we were talking about the completely hypothetical example of a spouse who does not clean the kitchen–

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Completely, completely hypothetical.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Yes. For the record, my husband is a great kitchen cleaner.

You started asking me some questions that I could see immediately were helping me rethink that problem. Is that kind of the key, just having a checklist of questions to ask yourself? How do you really start to put this into practice?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I think there are two steps in that. The first one is just to make yourself better at the method. Yes, you should kind of work with a checklist. In the article, I kind of outlined seven practices that you can use to do this.

But importantly, I would say you have to consider that as, basically, a set of training wheels. I think there’s a big, big danger in getting caught in a checklist. This is something I work with.

My co-author Paddy Miller, it’s one of his insights. That if you start giving people a checklist for things like this, they start following it. And that’s actually a problem, because what you really want them to do is start challenging their thinking.

So the way to handle this is to get some practice using it. Do use the checklist initially, but then try to step away from it and try to see if you can organically make– it’s almost a habit of mind. When you run into a colleague in the hallway and she has a problem and you have five minutes, like, delving in and just starting asking some of those questions and using your intuition to say, wait, how is she talking about this problem? And is there a question or two I can ask her about the problem that can help her rethink it?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Well, that is also just a very different approach, because I think in that situation, most of us can’t go 30 seconds without jumping in and offering solutions.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Very true. The drive toward solutions is very strong. And to be clear, I mean, there’s nothing wrong with that if the solutions work. So, many problems are just solved by oh, you know, oh, here’s the way to do that. Great.

But this is really a powerful method for those problems where either it’s something we’ve been banging our heads against tons of times without making progress, or when you need to come up with a really creative solution. When you’re facing a competitor with a much bigger budget, and you know, if you solve the same problem later, you’re not going to win. So, that basic idea of taking that approach to problems can often help you move forward in a different way than just like, oh, I have a solution.

I would say there’s also, there’s some interesting psychological stuff going on, right? Where you may have tried this, but if somebody tries to serve up a solution to a problem I have, I’m often resistant towards them. Kind if like, no, no, no, no, no, no. That solution is not going to work in my world. Whereas if you get them to discuss and analyze what the problem really is, you might actually dig something up.

Let’s go back to the kitchen example. One powerful question is just to say, what’s your own part in creating this problem? It’s very often, like, people, they describe problems as if it’s something that’s inflicted upon them from the external world, and they are innocent bystanders in that.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Right, or crazy customers with unreasonable demands.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Exactly, right. I don’t think I’ve ever met an agency or consultancy that didn’t, like, gossip about their customers. Oh, my god, they’re horrible. That, you know, classic thing, why don’t they want to take more risk? Well, risk is bad.

It’s their business that’s on the line, not the consultancy’s, right? So, absolutely, that’s one of the things when you step into a different mindset and kind of, wait. Oh yeah, maybe I actually am part of creating this problem in a sense, as well. That tends to open some new doors for you to move forward, in a way, with stuff that you may have been struggling with for years.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, we’ve surfaced a couple of questions that are useful. I’m curious to know, what are some of the other questions that you find yourself asking in these situations, given that you have made this sort of mental habit that you do? What are the questions that people seem to find really useful?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: One easy one is just to ask if there are any positive exceptions to the problem. So, was there day where your kitchen was actually spotlessly clean? And then asking, what was different about that day? Like, what happened there that didn’t happen the other days? That can very often point people towards a factor that they hadn’t considered previously.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: We got take-out.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: S,o that is your solution. Take-out from [INAUDIBLE]. That might have other problems.

Another good question, and this is a little bit more high level. It’s actually more making an observation about labeling how that person thinks about the problem. And what I mean with that is, we have problem categories in our head. So, if I say, let’s say that you describe a problem to me and say, well, we have a really great product and are, it’s much better than our previous product, but people aren’t buying it. I think we need to put more marketing dollars into this.

Now you can go in and say, that’s interesting. This sounds like you’re thinking of this as a communications problem. Is there a different way of thinking about that? Because you can almost tell how, when the second you say communications, there are some ideas about how do you solve a communications problem. Typically with more communication.

And what you might do is go in and suggest, well, have you considered that it might be, say, an incentive problem? Are there incentives on behalf of the purchasing manager at your clients that are obstructing you? Might there be incentive issues with your own sales force that makes them want to sell the old product instead of the new one?

So literally, just identifying what type of problem does this person think about, and is there different potential way of thinking about it? Might it be an emotional problem, a timing problem, an expectations management problem? Thinking about what label of what type of problem that person is kind of thinking as it of.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That’s really interesting, too, because I think so many of us get requests for advice that we’re really not qualified to give. So, maybe the next time that happens, instead of muddying my way through, I will just ask some of those questions that we talked about instead.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That sounds like a good idea.