- [email protected]

- 01457 821 818

- Consultant Profiles

- Book a Consultant

- News & Views

- Partnerships

- LOGIN SHOP LOGIN > COURSES LOGIN > ACCOUNT LOGIN > Forgot Login? Contact us

Assessing Writing… A Step in the Right Direction

Assessing writing in primary schools for year 2 and year 6– a step in the right direction… Part 1

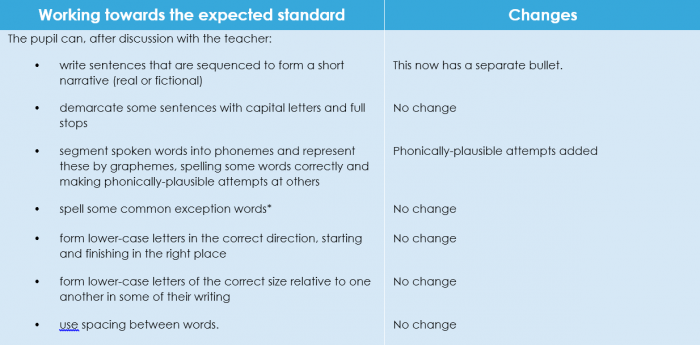

So, we have the promised revised assessment frameworks for writing for Year 2 and Year 6. First of all, what are the changes?

Without a doubt, this is an improvement. In general, we have, quite rightly, a shift towards, composition and effect in both Year 2 and Year 6. After all, all the grammatical structures and features we teach are precisely for that purpose; to create impact for particular purposes and audiences. There is also a welcome emphasis on the purposeful, appropriate and effective use of the grammar, vocabulary and punctuation rather than just having included it. There are no bulleted lists of required grammar or punctuation.

For Year 2, the exclamatory sentence beginning with how or what and including a verb has gone. What a relief that is! No more lists of possible manufactured exclamatory sentences at the end of writing about outings or experiences or comments on the behaviour of characters in stories.

Questions to be used when required. Presumably this means for a real reason; before hot seating or a trip or a visitor and when asking questions about books or questions they would like to find answers to in topics.

Narratives and recounts are mentioned for children at the expected standard with the expectation that these will be “simple” and “clear”. Explicit reference to expanded noun phrases has disappeared, yet even in a “simple” text written by a Year 2 pupil, there would be detail added using expanded noun phrases; after all, this is a grammar objective in Year 2.

Only those children working at greater depth now have to demonstrate that they can include words which use the suffixes taught in Year 2. This also is a relief, as to use the suffixes “ness” and “ment” involves changing adjectives or verbs into nouns. Constructing sentences with these is a sophisticated skill. For example:

The children were excited when the clowns appeared.

Everyone saw the excitement of the children when the clowns appeared.

The children clapped with excitement when the clowns appeared.

Other changes here are children writing for a range of purposes and editing and proof reading their own writing. It is unclear as to exactly what is intended by a range of purposes here, but obviously beyond the “simple” narratives and recounts already mentioned. The explicit inclusion of editing and proof reading has obvious implications for making sure that children are being taught how to edit and proof read effectively.

An important change for pupils working at greater depth, both in Year 2 and Year 6, is that of making use of models from reading. Again, an extremely welcome addition as this is how you become a good writer, drawing on what you read and making choices about how to use what you have read in your own writing. This makes our role in encouraging and offering some guidance in book choices absolutely crucial as well as how core texts are used in learning sequences.

For Year 6, there is clearer guidance about cohesive devices so that children who are working towards are expected to be able to use organisational features to structure a text and guide the reader whereas those who are at expected would be able to use vocabulary and grammar related cohesive devices to ensure that wring has “flow”. There are examples listed for greater clarity.

Grammatical features and language choices are no longer listed, but should be used appropriately and purposefully and are linked to the overall purpose of the text. Examples are given, but there is no bulleted list. This is also the case for punctuation which thankfully means we will not have to write about Lily-Mae who likes to wear a rose-coloured dress when she ventures out on her fact-finding missions.

Whilst there is now no specific mention of using “adverbs, preposition phrases and expanded noun phrases for precision and detail”, it would seem to me that this is implicitly included in writing for purpose and audience and language choices and the use of vocabulary and grammatical structures. So, no change really.

For children working at greater depth in Year 6, apart from the link to reading already discussed, there is specific reference made to understanding register and also to controlling levels of formality. These have replaced the previous expectation about managing shifts in formality. In reality, is that not still what is being expected?

There also seems to be a less rigid approach to the secure fit thinking. Best fit it most certainly is not. However, the statements below would perhaps seem to mean that, for example, a child who is an outstanding writer, but has real difficulties with spelling could be a greater depth writer.

- “A pupil’s writing should meet all the statements within the standard at which they are judged. However, teachers can use their discretion to ensure that, on occasion, a particular weakness does not prevent an accurate judgement being made of a pupil’s attainment overall. A teacher’s professional judgement about whether the pupil has met the standard overall takes precedence. This approach applies to English writing only.

- A particular weakness could relate to a part or the whole of a statement (or statements), if there is good reason to judge that it would prevent an accurate judgement being made.”

This seems fairer without reverting to the judgements which were made using APP. APP meant that a child could be judged at a certain “level” of attainment with poor spelling, inaccurate punctuation and sometimes even a core skill missing.

We need to wait for the promised further guidance and clarification and exemplification to see exactly what is required from these new assessment frameworks.

I sincerely hope that there will not be a grid produced. Most unfortunately, within 24 hours of the publication of the new frameworks, the internet was full of grids based on them. To my horror, some of these have bulleted or separated out the examples given. In any case, such grids should only be used to support those final judgements in June, not as a teaching tool.

What should we do now?

- Teach the Year 2 and Year 6 curriculum. Just because something is not included in the framework, does not mean that the children do not need to learn it!

- Use high-quality texts and draw on them on models for writing. This is great for all the children, not just those with potential to write at greater depth.

- keep the focus on purpose, audience and impact on the reader.

- Teach and develop editing and proof-reading skills.

- Read widely in the classroom and encourage children to read widely themselves.

- Remember that we are teaching the children new skills and not trying to assess them against a framework based on end of year expectations.

- Watch this space for part 2, when we have the promised guidance.

Continue the conversation on assessing writing in primary schools…

To discuss assessing writing in your school further, join me on Twitter @FocusRosf . I will be writing a second article with the promised guidance for assessing writing, so keep checking the blog for updates. For related resources, publications and courses, get in touch with the Focus Education office on 01457 821 818. You can enquire about Focus inset consultancy here .

Related Products

Judging Year 2 and Year 6 Writing

Writing at Greater Depth

Judging Year 1, 3, 4 and 5 Writing

Ros has over 30 years’ experience working in teaching and leadership roles in schools, both nationally and internationally, as well as leadership roles within Local Authority advisory teams. With extensive experience in all aspects of school improvement and contexts, as well as specialisms in English and EAL, Ros has developed inspirational, creative resources and training which puts English at the heart of the curriculum.

Recent Posts

- The Big Listen, but will they?

- Adaptive Teaching

- Breaking, Racing and Knowing When to Stop

The Importance of Retrieval in Supporting Children’s Long Term Memory

- Geography: The art of comparison

Related Articles

So we’ve assessed – what now?

Governors and the Curriculum

Character Education – The 6 Skills

Free download, book scrutiny.

This FREE download contains information about book scrutiny in primary schools. It includes the '7 strands of excellence' framework to support teachers in carrying out effective book scrutiny in classrooms. It also contains a summary explanation of book scrutiny and why it is necessary. Click the button at the top right of the page to download

Get all the latest news and updates

From focus education.

You’ll love our gold star loyalty rewards

Join for free - click here to register and start saving, privacy overview.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Learning in Wonderland

Educational website for elementary educators.

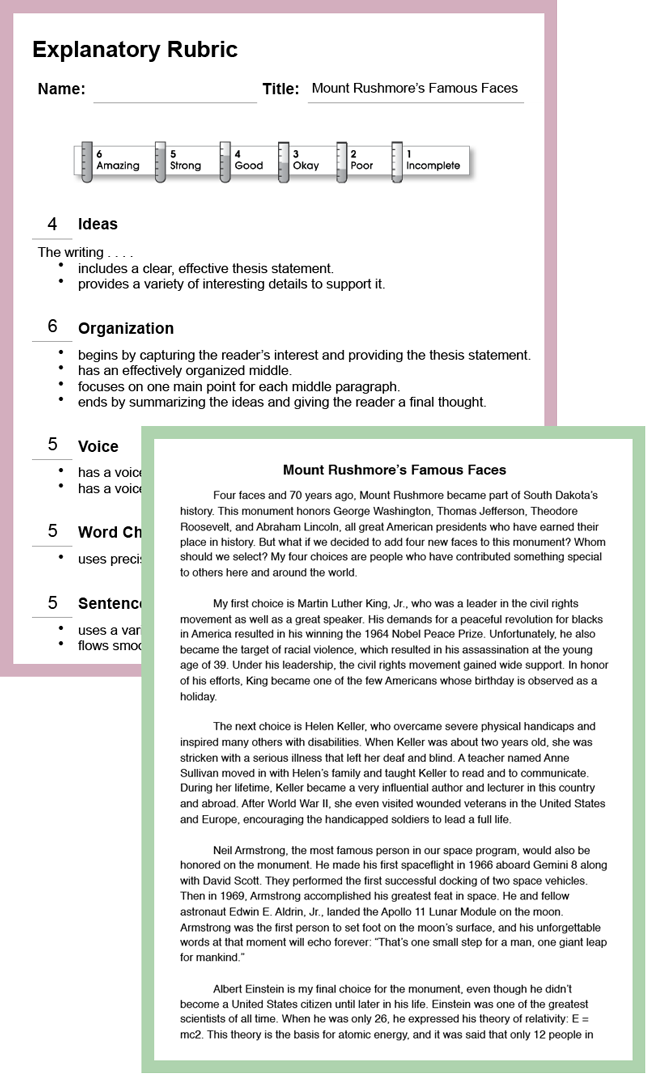

Teaching and Assessing Writing in the Primary Classroom

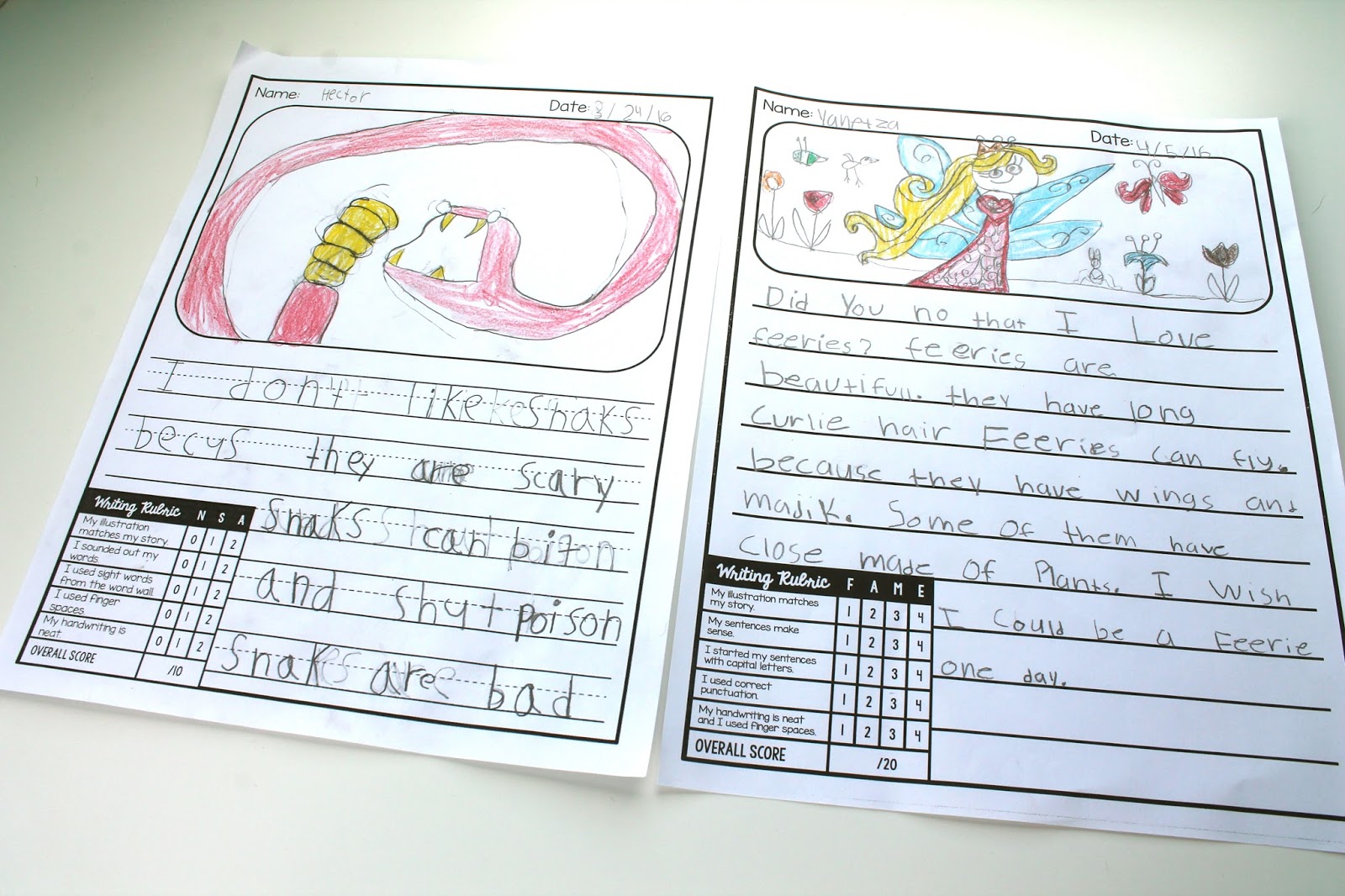

I have always loved reading my students’ writing, but knowing how or what to teach during writing was a different story. That was until I realized that I could use my students’ writing to guide my lessons. After a few years of experimenting I found a system that worked well for my students and myself and created a tool that has been a game changer!

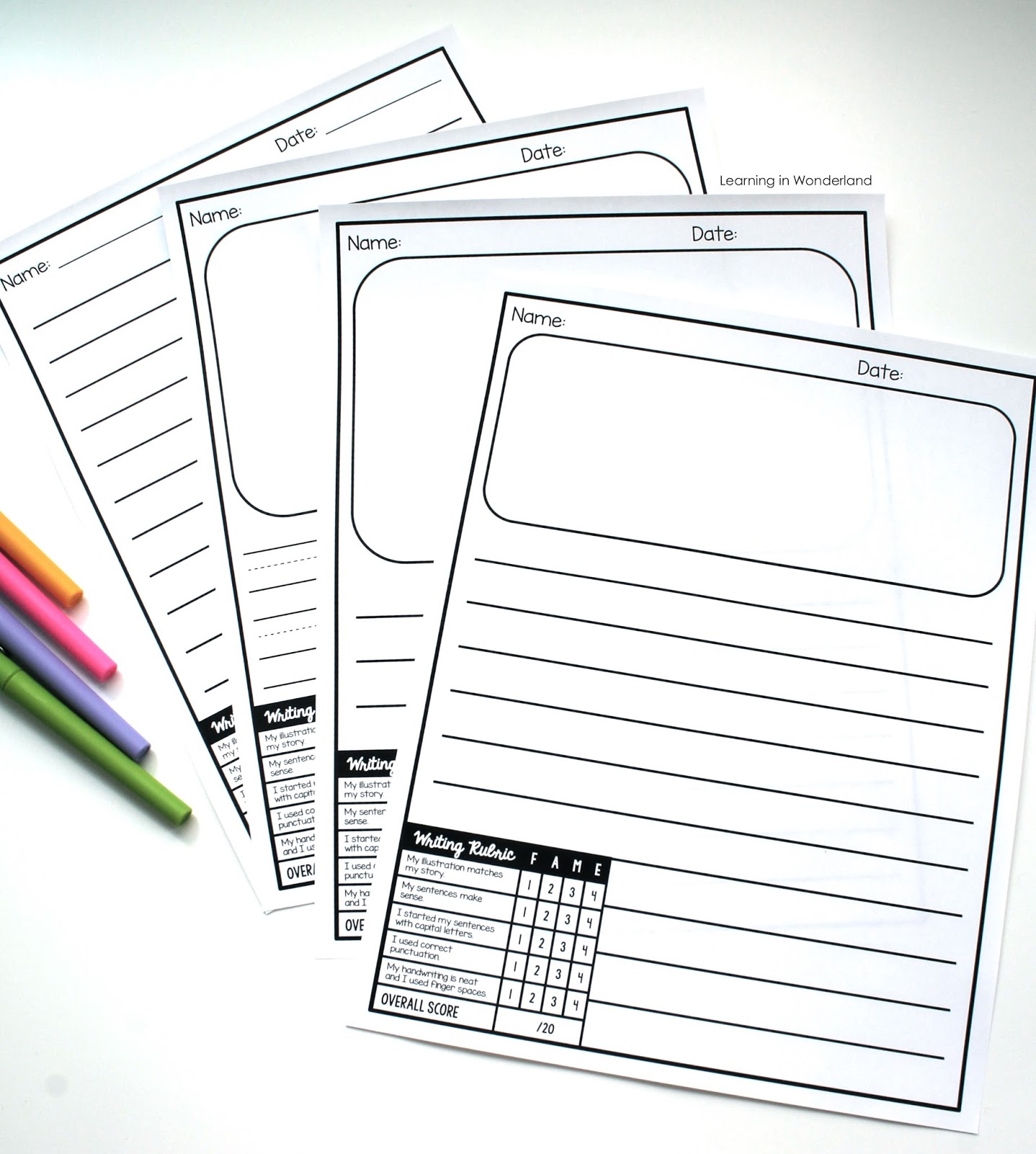

Each day, I teach a 5-10 minute lesson and model writing. The lessons are focused on a big idea for the week. Then my students write in their writer’s workshop journals.

I do not grade these journals. I want them to be a place for my kids to explore their creativity and experiment with the concepts we are learning. While I do not grade these journals, I do grade their writing assessments. The assessments are where I get future lesson ideas. This is where my writing templates come into play.

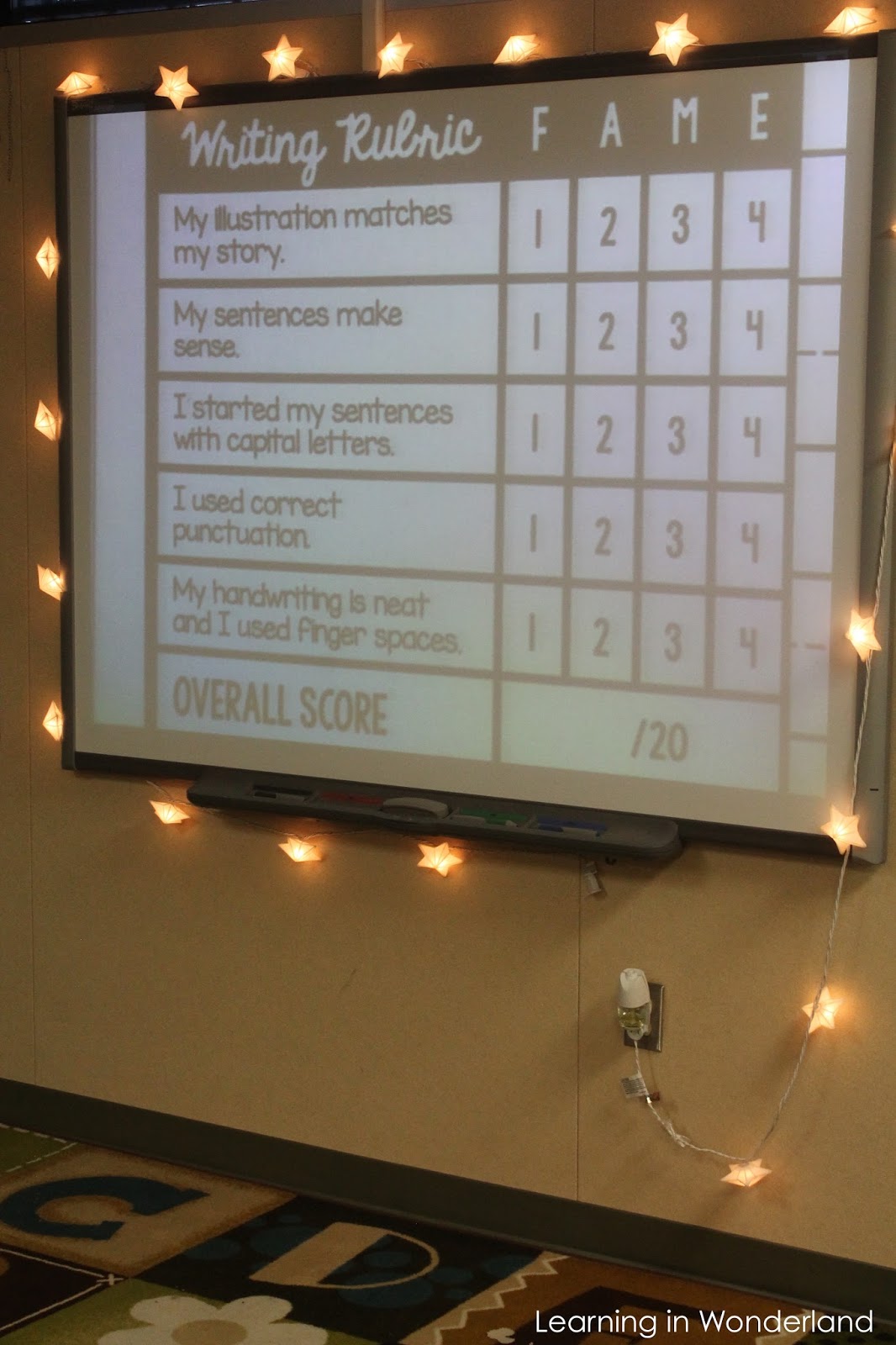

The rubrics are editable. So you can change all the text on it. I use the FAME scale because it is what our district uses. What is FAME? Here is the breakdown:

- F= Falling Far Below the Standard

- A= Approaching the Standard

- M= Meeting the Standard

- E= Exceeding the Standard

I find that using this grading system is much more accurate than giving an A, B, C etc. I don’t think I was ever given this much clarity about my grades, even in high school or college. How many of us remember being given a A, B, or C without any explanation? None of us liked that. Clear criteria eliminate that whole scenario.

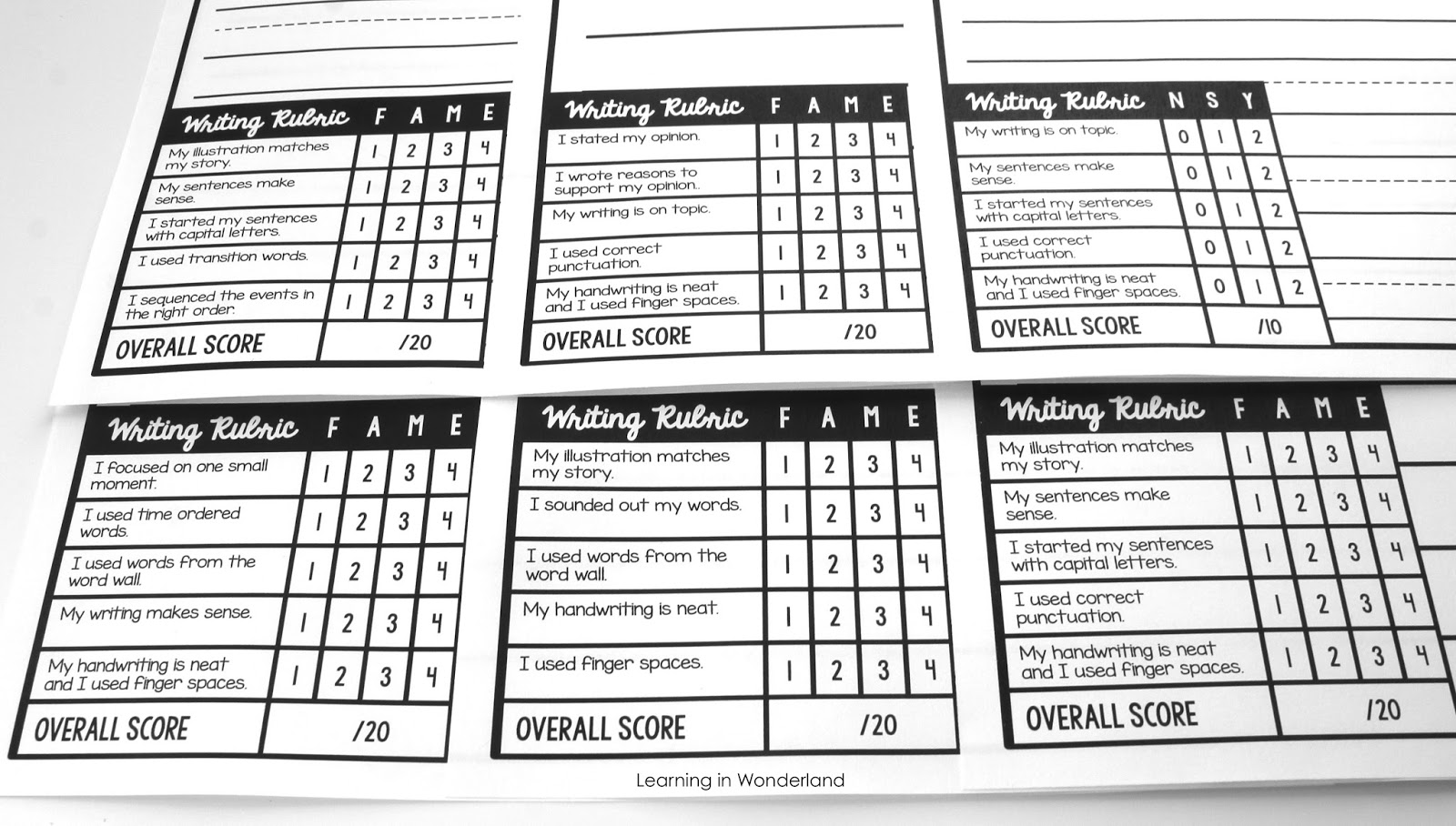

When I grade them I look to see what concepts my students need to work on. This is where I get my lesson skills to focus on to during whole group or small groups. I take that idea and focus in on it for the next week or so. The skills can range from sounding out our works, using the word wall, spacing their words appropriately, using commas in a series, etc. Prior to handing out the assessments, I enlarge the rubric on the Smartboard so that we can go over the criteria prior to their writing. Going over the rubric is vital because it makes the expectations clear to my students.

Children write at different ability levels. Differentation is so important in writing, just like any other subject area. This is why I provide my students differentiated writing templates when needed. My beginning writers use a template with a larger drawing area and primary lines. My more proficient writers use paper with a small drawing area that allows for more writing. I also make them double sided so that they can continue writing on the back.

Now let’s zoom in on the rubrics themselves. Each group has an individual rubric that is tailored to the specific skills they are working on. My beginning writers are working on different skills than my more fluent writers. There are also levels in between. Here is a peek at some of the different leveled rubrics I have used:

I originally embedded the rubrics to save myself time (no more cutting and stapling them onto my students’ writing), but those rubrics have been a great tool for my kids! They look over their rubrics and try to make sure that they are using the skills they have learned. It adds a whole new level of accountability. They make grading writing a little easier because the rubric takes the guess work out of grading. Another benefit is that my students’ parents have a clear snapshot of their child’s writing ability and a clear understanding their child’s grades. So many benefits from one sheet of paper!

There is no right or wrong way to teach writing. What is important is that we get our students writing every single day and we focus on their needs. If you are interested in my writing paper with editable rubrics, please click HERE for the link or the image below:

Instagram Fun

Learninginwonderland.

Popular on Pinterest

Find me on facebook.

Teaching creative writing in primary schools: a systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity

- Open access

- Published: 17 June 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Georgina Barton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2703-238X 1 ,

- Maryam Khosronejad 2 ,

- Mary Ryan 2 ,

- Lisa Kervin 3 &

- Debra Myhill 4

4506 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Teaching writing is complex and research related to approaches that support students’ understanding and outcomes in written assessment is prolific. Written aspects including text structure, purpose, and language conventions appear to be explicit elements teachers know how to teach. However, more qualitative and nuanced elements of writing such as authorial voice and creativity have received less attention. We conducted a systematic literature review on creativity and creative aspects of writing in primary classrooms by exploring research between 2011 and 2020. The review yielded 172 articles with 25 satisfying established criteria. Using Archer’s critical realist theory of reflexivity we report on personal, structural, and cultural emergent properties that surround the practice of creative writing. Implications and recommendations for improved practice are shared for school leaders, teachers, preservice teachers, students, and policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Early childhood creativity: challenging educators in their role to intentionally develop creative thinking in children.

Nicole Leggett

The Efficacy of Inquiry-Based Instruction in Science: a Comparative Analysis of Six Countries Using PISA 2015

Mary Oliver, Andrew McConney & Amanda Woods-McConney

The Educational Affordances and Challenges of ChatGPT: State of the Field

Helen Crompton & Diane Burke

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creative writing in schools is an important part of learning, assessment, and reporting, however, there is evidence globally to suggest that such writing is often stifled in preference to quick on-demand writing, usually featured in high-stakes testing (Au & Gourd, 2013 ; Gibson & Ewing, 2020 ). Research points to this negatively impacting particularly on students from diverse backgrounds (Mahmood et al., 2020 ). When teachers teach on-demand writing typical pedagogical traits are revealed, those that are often referred to as formulaic (Ryan & Barton, 2014 ). When thinking about creative writing, however, Wyse et al. ( 2013 ) noted that it involves the absence of structure and teaching creative writing requires an ‘open’ pedagogical approach for students to be given imaginative choice. By this, they mean that teachers need to consider less formulaic ways to teach writing so that students can experience different opportunities and ways to write creatively. They argued that if students are not given the flexibility to experiment through writing then their creativity might be stifled. Similarly, Barbot et al. ( 2012 ), who carried out a study with a panel of 15 experts of creative writing, posited that creative writing is when students draw on their imagination and other creative processes to create fictional narratives or writing that is ‘unusually original’. They also noted that creative writing is important for the development of students’ critical and creative thinking skills and ways in which they can approach life in creative ways.

Creative writing is defined in various ways in literature. Wang ( 2019 ) defined creative writing as a form of original expression involving an author’s imagination to engage a reader. Other definitions of creative writing involve the notion of children’s imagination, choice, and originality and much research has explored the concept of creativity within and through the writing process.

While creative writing is defined in various ways, and the many ways that it is treated in literacy education, this article is not concerned with the nature of the term per se. Rather, it focusses on research about creative writing and creativity in writing to understand how research unpacks the personal and contextual characteristics that surround creative writing practices. To this aim, we adopt a broad definition of creative writing as a form of original writing involving an author’s imagination and self-expression to engage a reader (Wang, 2019 ). Creative writing is important for children’s development (Grainger et al., 2005 ), allowing them to use their imagination and broaden their ability to problem-solve and think deeply. Creativity in writing refers to specific aspects within a writing product that can be deemed creative. Some examples include the use of senses and how a writer might engage a reader (Deutsch, 2014 ; Smith, 2020 ).

International research on teaching writing has indicated a loss in innovative or creative pedagogical practices due to the pressure on teachers to teach prescribed writing skills that are assessed in high-stakes tests (Göçen, 2019 ; Stock & Molloy, 2020 ), often resulting in specific trends including teaching a genre approach to writing (Polesel et al., 2012 ; Ryan & Barton, 2014 ). A comprehensive meta-analysis by Graham et al ( 2012 ), designed to identify writing practices with evidence of effectiveness in primary classrooms, found that explicitly teaching imagery and creativity was an effective teaching practice in writing. In addition, a review of methods related to teaching writing conducted by Slavin et al. ( 2019 ) included studies that statistically reported causal relationships between teacher practice and student outcomes. Common themes in Slavin et al’s ( 2019 ) quest for improving writing included comprehensive teacher professional development, student engagement and enjoyment, and explicit teaching of grammar, punctuation, and usage. While they did not specifically cite creativity, motivating environments and cooperative learning were important characteristics of writing programs.

This systematic literature review aims to share empirical international research in the context of elementary/primary schools by exploring creativity in writing and the conditions that influence its emergence. It specifically aims to answer the question: What influences the teaching of creative writing in primary education? And how can reflexivity theorise these influences? The review shares scholarly work that attempts to define personal aspects of creative writing including imagination, and creative thinking; discusses creative approaches to teaching writing, and shows how these methods might support students’ creative writing or creative aspects of writing.

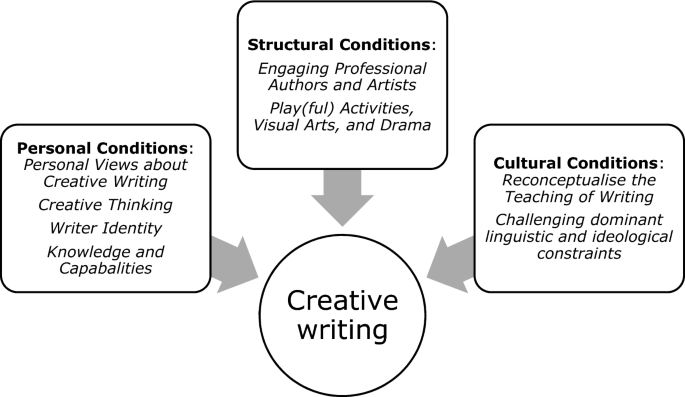

Writing is a complex process that involves students making decisions about word choice, sentence, and text structure, and ways in which to engage readers. Such decisions require a certain amount of reflection or at times deeper reflexive judgments by both teachers and students. Consequently, we draw on Archer’s ( 2012 ) critical realist theory of reflexivity to guide our review as research shows that reflexive thinking in practice can improve writing outcomes (Ryan et al., 2021 ). Archer ( 2007 ) highlights how reflexivity is an everyday activity involving mental processes whereby we think about ourselves in relation to our immediate personal, social, and cultural contexts. She suggests we make decisions through negotiating the connected emergences of personal properties (PEPs) related to the individual, structural properties (SEPs) related to the contextual happenings and cultural properties (CEPs) related to ideologies, each of which is influenced by the other developments. These decisions influence, and are influenced by, our subsequent actions. In applying reflexivity theory to writing (see Ryan, 2014 ), we cannot simply focus on the writing product, but should also interrogate the process of writing, that is, the influences on decision-making and design which are enabled or constrained through pedagogical practices in the classroom. Writing practices and outputs are formed through the interplay of personal, structural, and cultural conditions. Student decisions and actions about writing ensue through the mediation of personal (e.g. beliefs, motivations, interests, experiences), structural (e.g. curriculum, programs, testing regimes, teaching strategies, resources), and cultural (e.g. norms, expectations, ideologies, values) conditions. Therefore, teachers play an important role in facilitating the interplay of these conditions for their students and recontextualising curricula and policy (Ryan et al., 2021 ). For example, by enabling students’ agency and creating an authentic purpose for writing, teachers can balance the personal conditions of students (such as their motivation and interest) against the structural effects of the curriculum requirements. Using a reflexive approach to investigating the literature on creative writing we aim to reveal the personal, structural, and cultural conditions surrounding the study and the practice of creative writing. We argue that it is through the understanding of these conditions that we can theorise how a. students might make their writing more creative and b. how teachers might establish classroom conditions conducive to creativity.

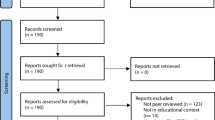

The approach taken for this paper was guided by the PRISMA method (Moher et al., 2009 ) for conducting systematic literature reviews (see Table 1 ).

Our electronic search involved several databases: researchers’ library online catalogue, EBSCO host ultimate, ProQuest, Eric, Web of Science, Informit, and ScienceDirect. Using the following search terms: creativ* AND (‘teaching methods’ OR pedagog*) AND writing AND (elementary OR primary) to search titles and abstracts as well as limiting the search to peer-reviewed articles written in English within a 10-year timeframe (2011–2020), we initially retrieved 172 articles. Information about all 172 articles was input into a data spreadsheet including author, article title, journal title, volume and issue number, and abstract. Once completed, these articles were divided into two equal groups and two researchers were assigned to review the articles for relevancy against the following inclusion criteria:

Studies were peer-reviewed empirical research published in English;

Participants were primary students and/or teachers;

Students were not specifically English as a Second or Additional Language/Dialect learners (samples of culturally and linguistically diverse students in primary classrooms were included);

Studies were not carried out in curriculum areas other than English; and

Studies did not have a specific focus on digital technologies in the classroom.

For this systematic review, we were interested in the ways in which teachers thought about, understood, and taught the ‘creative’ aspect of writing.

The 25 studies that met the inclusion criteria were synthesised to review what influences the improvement of creative writing in primary education. We analysed the papers for how creative writing and/or creative aspects in writing were viewed as well as how teachers might best support students to develop reflexive capacities to improve the creative aspects of writing. We also identified any personal, structural, and/or cultural emergences that might impact on the effectiveness of students’ creative writing. Two of the authors read the entire articles and identified four main categories of research which were (1) understanding creative writing; (2) creative thinking and its contribution to writing; (3) creative pedagogy; and (4) what students can do to be more creative in their writing. These were cross-checked by the entire research team. Some of the papers fit more than one of these themes. In the next section, each theme is introduced and defined and then the articles that fall within the theme are reviewed.

Overall a total number of 25 articles had overlapping themes that included various personal and contextual aspects. Figure 1 shows what we have identified as the key themes under each category. In the next sections, we represent papers based on their main theme.

The personal, structural, and cultural conditions surrounding creative writing

Personal emergent properties

A total number of 13 articles were about what students can do to be more creative in their writing (Mendelowitz, 2014 ; Steele, 2016 ) and how teachers’ and students’ personal characteristics relate to the development of creative writing. These articles were mainly focussed on the personal emergent aspects of writing (Alhusaini & Maker, 2015 ; Barbot et al., 2012 ; Cremin et al., 2020 ; DeFauw, 2018 ; Dobson, 2015 ; Dobson & Stephenson, 2017 , 2020 ; Edwards-Groves, 2011 ; Healey, 2019 ; Lee & Enciso, 2017 ; Macken-Horarik, 2012 ; Ryan, 2014 ). The personal aspects identified in our review were (1) personal views about creative writing, (2) creative thinking, (3) writer identity, (4) learner motivation and engagement, and (5) knowledge and capabilities.

Personal views about creative writing

From our systematic review, we identified three articles exploring views about what creative writing is, and more specifically the role that it plays and the elements that make creative writing, in primary classrooms. One of these studies was focussed on the views and experiences of experts in writing (Barbot et al., 2012 ), whereas the other two investigated students’ perspectives and experiences (Alhusaini & Maker, 2015 ; Healey, 2019 ). Barbot et al’s ( 2012 ) work, for example, recognised that creative writing involves both cognitive and metacognitive abilities. This was determined by the expert panel of people whose work related to writing including teachers, linguists, psychologists, professional writers, and art educators. The panel were asked to complete an online survey that rated the relative importance of 28 identified skills needed to creatively write. Six broad categories were identified as a result of the responses and the rank given to each factor by the expert groups (See Table 2 ). They acknowledged that these features cross over various age groups from children to professional writers.

Findings suggested that each independent rater weighted different key components of creative writing as being more or less important for children. Overall, the findings showed.

a global ‘consensus’ across the expert groups indicated that creative writing skills are primarily supported by factors such as observation, generation of description, imagination, intrinsic motivation and perseverance, while the contributions of all of the other relevant factors seemed negligible (e.g. intelligence, working memory, extrinsic motivation and penmanship). (p. 218)

One factor that was ranked as critical by most respondents, but underemphasised by teachers, was imagination. Teachers’ work in classrooms around creative writing is complex due to the difficulty in defining imagination (Brill, 2004 ). Teachers also under-rated other aspects related to creative cognition.

Another study that explored students’ creativity in writing was conducted by Alhusaini and Maker ( 2015 ) in the south-west of the United States. Participants included 139 students with mixed ethnicities including White, Mexican American, and Navajo. This study involved six elementary/primary school teachers judging students’ writing samples of open-ended stories. To assess the work a Written Linguistic Assessment tool, which was based on the Consensual Assessment Technique [CAT] (Amabile, 1982 ) was implemented. According to Baer and McKool ( 2009 ), The CAT involves experts rating written artefacts or artistic objects by using their ‘sense of what is creative in the domain in question to rate the creativity of the products in relation to one another’ (p. 4). Interestingly, Alhusaini and Maker ( 2015 ) found the CAT to be effective in relation to interrater reliability. The authors do not share what the Judge’s Guidelines to Assess Students’ Stories entail. They mention the difference between technical quality and creativity and note that assessors were able to distinguish the differences between the two, but the reader is not made aware of the aspects of each quality. Overall, the study revealed that one of the most challenging problems in the field of creativity and writing is trying to measure creativity across cultures by using standardised tests. Such studies could have implications for other students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds as teachers become more aware of cultural nuances in constituting ‘creative’ in creative writing.

The final study we identified in this category was by Healey ( 2019 ). Healey employed an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and explored how eight children (11–12 Years of age) experienced creative writing in the classroom. He shared how children’s writing experiences were based on ‘the affect, embodiment, and materiality of their immediate engagement with activities in the classroom’ (p. 184). Results from student interviews showed three themes related to the experience of writing: the writing world (watching, ideas from elsewhere, flowing); the self (concealing and revealing, agency, adequacy); and schooled writing (standards, satisfying task requirements, rules of good writing). The author stated that children’s consciousness shifts between their imagination (The Writing World) and set assessment tasks (Schooled Writing). Both of these worlds affect the way children experience themselves as writers. Further findings from this work argued that originality of ideas and use of richer vocabulary improved students’ creative writing. Vocabulary improvement included diversity of word meanings, appropriate usage of words, words being in line with the purpose of the text; while originality of ideas featured creative and unusual (original) ideas—which in many ways is difficult to define.

Overall, when concerned with personal views and attitudes in creative writing, the two studies by Healey ( 2019 ) and Barbot et al. ( 2012 ) show contrasting findings about ‘imagination’ captured through the view of students and teachers, respectively. While Healey’s ( 2019 ) study suggests that children shift between their imagination and set assessment tasks in creative writing, Barbot et al. ( 2012 ) highlight the lack of attention to imagination among their participated teachers. Although these results cannot be generalised, they highlight the significance of understanding personal emergent properties that both students and teachers bring to the classroom and the way that they interact to affect the experience of creative writing for learners. From this theme, we suggest the importance of educators acknowledging students’ imagination through their definition of creative writing as well as providing quality time for students to choose what they write through imaginative thought. We now turn to creative thinking and related pedagogical approaches to teaching creative writing from the research literature.

Creative thinking

We identified two articles that were focussed on creative thinking and its contribution to writing (Copping, 2018 ; Cress & Holm, 2016 ). Copping ( 2018 ) explored writing pedagogy and the connections between children’s creative thinking, or a ‘new way of looking at something’ (p. 309), and their writing achievement. The study involved two primary schools in Lancashire, one in an affluent area and one in an underprivileged area. Approximately 28 children from each school were involved in two, 2-day writing workshops based on a murder mystery the children had to solve. Findings from this study revealed that to improve students’ writing achievement (1) a thinking environment needs to be created and maintained, (2) production processes should have value, (3) motivation and achievement increase when there is a tangible purpose, and (4) high expectations lead to higher attainment.

Cress and Holm’s ( 2016 ) study described a curricular approach implemented by a first-grade teacher and their class comprised 13 girls and 11 boys. The project known as the Creative Endeavours project aimed to develop creative thinking by (1) creating an environment of respect with a positive classroom climate. (2) offering new and challenging experiences, and (3) encouraging new ideas rather than praise. The authors argued that through peer collaboration and the flexibility to choose their own projects, children can become more authentically engaged in the writing process. The children wrote about their experiences and their choices, and reflected upon the projects undertaken. In this study, it was revealed that the children showed diversity in their writing assignments including presentation through sewing, photography, and drama. While there were only two papers in this particular theme, their findings are supported by systematic reviews (Graham et al., 2012 ; Slavin et al., 2019 ) that emphasise not only new ways of exploring a range of concepts for learning but also the creation of motivating environments for improving writing (Copping, 2018 ). In addition to the significance of positive and encouraging learning environments, these two studies suggest that setting ‘high expectations’ or ‘challenging experiences’ are conducive to creative thinking however, teachers would need to set appropriate, reflexive conditions for this to occur.

Writer identity

Studies in this category revolve around choice and learner writer identity. The study carried out by Dobson and Stephenson ( 2017 ) focussed on developing a community of writers involving 25 primary school pupils from low socio-economic backgrounds. The project was offered over 2 weeks and featured a number of creative writing workshops. The authors applied the theoretical frameworks of practitioner enquiry and discourse analysis to explore the children’s creative writing outputs. They argued that the workshops, which promoted intertextuality and freedom for the children as writers, enabled a shifting of their ‘writer’ identities (Holland et al., 1998). Dobson and Stephenson ( 2017 ) showed that allowing students to make decisions and choices in regard to authentic writing purposes supported a more flexible approach. They recommend stronger partnerships between schools and universities in relation to research on creative writing, however, it would be important for these relationships to be sustainable.

The second paper on this theme is by Ryan ( 2014 ) who noted that writing is a complex activity that requires appropriate thinking in relation to the purpose, audience, and medium of a variety of texts. Writers always make decisions about how they will present subject matter and/or feelings through all of the modes. Ryan ( 2014 ) suggested that writing is like a performance ‘whereby writers shape and represent their identities as they mediate social structures and personal considerations’ (p. 130). The study analysed writing samples of culturally and linguistically diverse Australian primary students to uncover the types of identities students shared. It found that three different types of writers existed—the school writers who followed teacher instructions or formulas to produce a product; the constrained writers who also followed instructions and formulas but were able to add in some authorical voice; and the reflexive writers who could show a definite command of writing and showed creative potential. Ryan ( 2014 ) argued that teachers’ practices in the classroom directly influence the ways in which students express these identities. She stated that when students are provided choices in writing, they are more able to shape and develop their voices. Such choices would need to include quality time and support to be reflexive in the decisions being made by the students.

The Teachers as Writers project (2015–2017) was conducted by Cremin, Myhill, Eyres, Nash, Wilson, and Oliver. In a recent paper ( 2020 ), the team reported on a collaborative partnership between two universities and a creative writing foundation. Professional writers were invited to engage with teachers in the writing process and the impact of these interactions on classroom teaching practices was determined. Data sets included observations, interviews, audio-capture (of workshops, tutorials and co-mentoring reflections), and audio-diaries from 16 teachers; and a randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 32 primary and secondary classes. An intervention was carried out involving teachers writing in a week long residence with professional writers, one-on-one tutorials, and extra time and space to write. They also continued learning through two Continuing Professional Development (CPD) days. Results showed that teachers’ identities as writers shifted greatly due to their engagement with professional authors. The students responded positively in terms of their motivation, confidence, sense of ownership, and skills as writers. The professional authors also commented on positive impacts including their own contributions to schools. Conversely, these changes in practice did not improve the students’ final assessment results in any significant way. The authors noted that assuming a causal relationship between teachers’ engagement with writing workshops and students’ writing outcomes was spurious. They, therefore, developed further research building on this learning.

Knowledge and capabilities

The role of knowledge and capability is central to the articles in this category. In Australia, Macken-Horarik ( 2012 ) reported on the introduction of a national curriculum for English. This article drew on Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) by investigating the potential of Halliday’s notion of grammatics for understanding students’ writing as acts of creative meaning in context. Macken-Horarik ( 2012 ) argued that students needed to know deeply about language so that they could make creative decisions with their writing. She outlined that a ‘good enough’ grammatics would assist teachers in becoming comfortable with ‘playful developments in students’ texts and to foster their control of literate discourse’ (p. 179).

A project carried out by Edwards-Groves in 2011 highlights the role of knowledge about digital technologies in writing practices. 17 teachers in primary classrooms in Australia were asked to use particular digital technologies with their students when constructing classroom texts. Findings showed that an extended perspective on what counts as writing including the writing process was needed. Results revealed that collaborative methods when constructing diverse texts required teachers to rethink pedagogies towards writing instruction and what they consider as writing. It was argued that technology can be used to enhance creative possibilities for students in the form of new and dynamic texts. In particular, it was noted that teachers and students should be aware that digital technologies can both constrain and/or enable text creation in the classroom depending on a number of variables including knowledge and understanding, locating resources and logistical issues such as connectivity and reliability.

In addition, Mendelowitz’s ( 2014 ) study argued that nurturing teachers’ own creativity assisted their ability to teach writing more generally. She noted several ‘interrelated variables and relationships that still need to be given attention in order to gain a more holistic understanding of the challenges of teaching creative writing’ (p. 164). According to Mendelowitz ( 2014 ), elements that impacted on these challenges include teachers’ school writing histories, conceptualisations of imagination, classroom discourses, and pedagogy. Documenting teachers’ work through interviews and classroom observations by the researcher, the study found that teachers need to be able to define imagination and imaginative writing and know what strategies work best with their students. She noted that the teacher’s approaches to teaching writing ‘powerfully shaped by the interactions between their conceptualisations and enactments of imaginative writing pedagogy’ (p. 181) and that these may either limit or create a space for students to be more creative with their writing.

Such Personal Emergent Properties show that individual attributes of both teachers and students are important in learning creative writing. The next section of the paper explores the articles that shared various structural and cultural properties.

Structural emergent properties

In the subset of structural emergent properties, we mainly identified pedagogical approaches for creative writing that explored primary school learning and teaching (Christianakis, 2011a ; Christianakis, 2011b ; Coles, 2017 ; DeFauw, 2018 ; Hall & Grisham-Brown, 2011 ; Portier et al., 2019 ; Rumney et al., 2016 ; Sears, 2012 ; Steele, 2016 ; Southern et al., 2020 ; Yoo & Carter, 2017 ). These pedagogical approaches were aimed at addressing issues related to personal emergent properties such as motivation and engagement, and confidence in writing. The two categories of writing pedagogies were those that engaged professional authors and artists in teaching about creative writing, and the approaches that involved play(ful) activities, and use of visual arts, and drama.

Engaging professional authors and artists

Interestingly, many of the studies used literary forms and/or professional creative authors to spike interest and motivation in the students. Coles’ ( 2017 ) study, for example, used a garden-themed poetry writing project to support 9–10-year-old children’s creative writing in a London primary school. The 5-week project partnered with a professional creative writing organisation that facilitated the Ministry for Stories (MoS) writing centres across the USA. The study found that the social relationships created through this partnership allowed for a more inclusive and socially generative model of creativity. This meant that teachers should not just include creative aspects in assessment rubrics but rather recognise that creativity is encouraged through imagination and working with others. The researchers found improvements in the children’s participation in classroom writing activities as well as diversity in the ways they expressed their writing. The approach valued ‘rich means of expression rather than a set of rules to be learnt’ (p. 396). They also acknowledged issues associated with school–community partnerships including the sustainability of the practice.

Similarly, Rumney et al. ( 2016 ) found that using creative multimodal activities increased students’ confidence and motivation for writing. The study implemented the Write Here project with over 900 children in 12 primary and secondary schools. The study involved the children visiting local art galleries to work with professional authors and artists. Case studies were presented about pre-writing activities, the actual gallery work and post-gallery follow-up sessions. It aimed to improve students’ social development and literacy outcomes through diverse learning activities such as visual art and play in different contexts such as art galleries and classrooms. Like Coles’ ( 2017 ) study, this project showed that creative activities (e.g. talking about and acting out pictures; using story maps; backwards writing and planning) engaged students more than just teaching skills.

In addition, DeFauw’s ( 2018 ) study had student-centred learning and leadership at the core when working with a children’s book author for one year. The collaboration involved three face-to-face sessions with the author as well as online communication through blog posts. Data included recorded interactions, readings and pre and post interviews with teachers ( n = 9), students ( n = 36), and the author. The partnership showed that students’ interest was activated and sustained due to the situational context as well as the extended time given to students to interact with the author. The project improved students’ interest in and motivation to write as a result of engaging with authors and hearing about their own experience and writing strategies. It also found that teachers gained more confidence to support students’ exploration of writing in more creative ways. The creative pedagogies were also used in addressing issues related to creative writing outcomes for students, including teachers’ lack of confidence about pedagogies (Southern et al., 2020 ). Through a creative social enterprise approach, the authors facilitated professional development and learning involving artist-led activities for students. The program called Zip Zap had been implemented in schools in Wales and England, and data were collected through focus groups with teachers, students, and parents/carers. Observations of some of the professional development workshops were also video recorded. Third space theory was used to describe the collaborative practice between educators and artists that supported students’ creative writing outcomes. It was noteworthy that involving ‘creative’ practitioners largely focussed on the specific strategies that could be used in classrooms, to which our next section now turns.

Play(ful) activities, visual arts, and drama

Much research explores how to best support students who find writing difficult. Sears’ research ( 2012 ) is a case in point. The author shared how visual arts may be an effective way to improve struggling students with writing. They argued that the visual arts can provide ways of ‘accessing and expressing [student] ideas and ultimately opening a world of creative possibilities’ (p. 17). In the study, six third-grade students engaged with drawing and painting as pre-writing strategies, leading to the creation of poems based on the artworks. The students’ final poems were assessed and showed improved knowledge of all 6 technical categories in writing: ideas, organisation, fluency, voice, word choice, and conventions. The author also argued that students’ motivation to write increased as a result of the visual art activities.

A study by Portier et al. ( 2019 ) investigated approaches to teaching writing that were motiving and engaging for students. Involving 10 northern rural communities in Canada, the project implemented collaborative, play(ful) learning activities alongside sixteen teachers and their students. Interestingly, the study, like many others in our review, found a disconnect ‘between the achievement of curricular objectives and the implementation of play(ful) learning activities’ (p. 20); an approach valued in early childhood education. The students were supported through action research projects in creating texts with different purposes. Students’ motivation as well as samples of work were analysed and showed that student interest areas and collaborative approaches benefited both teachers and students. Further research on how reflexive thinking might have influenced these benefits is recommended.

Similarly, Lee and Enciso ( 2017 ) highlighted the importance of motivation and engagement in their study. In a collaboration with Austin Theatre Alliance, Lee and Enciso ( 2017 ) investigated how dramatic approaches to teaching, such as through expanded imagination and improvisation, can improve students’ story writing. They argued that the students’ motivation to write was also increased. The study was carried out through a controlled quasi-experimental study over 8 weeks of story-writing and drama-based programs. 29 third-grade classrooms in various schools, located in an urban district of Texas, were involved. The study also pre- and post-tested the students’ writing self-efficacy through story building. The study found that students were more able to use their cultural knowledge such as ‘culturally formed repertoires of language and experience to explore and express new understandings of the world and themselves…’ (p. 160) for creative writing purposes but needed more quality resources to support opportunities such as the Literacy for Life program. A most important finding was that for children who experience poverty, drama-based activities developed and led by teaching artists were extremely powerful and allowed the students to express themselves in entertaining ways. We do note that ‘entertainment’ and or engagement might mean different things for different students so reflexive approaches to deciding what these are would be necessary.

Steele’s ( 2016 ) study also looked at supporting teachers’ work in the classroom. Involving 6 out of 20 teacher workshop participants in Hawaii, this exploratory case study utilised observations, interview, and portfolio analyses of teacher and student work. Findings from the study showed that some teachers relished moving away from everyday ‘typical’ practice and increased student voice and choice. Other teachers, however, found it difficult to take risks and hence respond to student needs and ideas.

Dobson and Stephenson’s ( 2020 ) study focussed on the professional development of primary school teachers using drama to develop creative writing across the curriculum. The project was sponsored by the United Kingdom Literacy Association and ran for two terms in a school year. Researchers based the research on a collaborative approach involving academics and four teachers working with theatre educators to use process drama. Data sets included lesson observations, notes taken during learning conversations, and interviews with the teachers. The findings showed that three of the four teachers resisted some of the methods used such as performance; resulting in a lack of child-centred learning. The remaining teacher could take on board innovative practice, which the researchers attributed to his disposition. The study argued that these teachers, while a small participant group, needed more support in feeling confident in implementing new and creative approaches to teaching writing.

The final study, identified as addressing creative pedagogies for creative writing, was carried out by Yoo and Carter ( 2017 ) as professional development for teachers. Data included teacher survey responses and field notes taken by the researchers at each workshop (note: number of workshops and participants is unknown). The program aimed to investigate how emotions play a role in teachers’ work when teaching creative writing. The researchers found that intuitive joint construction of meaning was important to meet the needs of both primary and secondary teachers. A community of practice was established to support teachers’ identities as writers (see also Cremin et al., 2020 ). Findings showed that teachers who already identified as writers engaged more positively in the workshop.

These studies presented some approaches for teachers to consider how to teach creative writing. For example, the need to value unique spaces for students to write, including authentic connections with people and places outside of school environments was shared. Further, the need for quality stimuli and time for writing was acknowledged. Several other studies identified that blended teaching approaches to support student learning outcomes in the area of creative writing is important for schools and teachers to consider. We do acknowledge there may be other methods available to support students in creative writing, however, understanding what types of SEPs are impacting on teaching creative writing is an important step in determining improvements in schools.

Cultural emergent properties

Christianakis ( 2011a , 2011b ) wrote two papers about children’s creative text development with an emphasis on the cultural aspects. The first was an ethnographic study across 8 months with a year five class in East San Francisco Bay. The study included audio recording the students’ conversations and analysing over 900 samples of work. In the classroom, students were involved in a range of meaning-making practices including those that were arts-based and multimodal. The conversations with the students involved the researcher asking questions such: tell me more about this drawing, how did you come up with the idea? or why did you make this choice? The study found that there was a need for schools to reconceptualise the teaching of writing ‘to include not only orthographic symbols, but also the wide array of communicative tools that children bring to writing’ (p. 22). The author argued that unless corresponding institutional practices and ideologies were interrogated then improved practice was unlikely.

Christianakis’ ( 2011b ) second article, from the same project, explored more specifically the creation of hybrid rap poems by the children. She explicated how educators needed to negotiate and challenge dominant practices in primary classroom literacy learning. Like many studies before, a strong recommendation was to be more inclusive of youth popular cultures and culturally relevant literacies for students to be more engaged in creative writing practices. For Christianakis, culturally relevant literacies meant practices that embraced diversity in class and race and accounted for, and challenged, the dominant hegemonic curriculum that ‘privileges a traditional canon’ (p. 1140).

In summary, we found several themes under PEPs that could be considered for further research including those outlined in Table 3 below.

Discussion and implications for classroom practice

From this systematic literature review, several positions were exposed about the personal, structural, and cultural influences (Archer, 2012 ; Ryan, 2014 ) on teaching creative writing. These include limited teacher and student knowledge of what constitutes creative writing (Personal Emergent Properties [PEPs]), and no shared understanding or expectation in relation to creative writing pedagogy in their context (Cultural Emergent Properties [CEPs]). The negative impact of standardised testing and trending approaches on how teachers teach writing (CEP; Structural Emergent Properties [SEPs]) could also be considered (see AUTHORS 1 and 3, 2014 for example). In addition, teachers’ poor self-efficacy in terms of teaching creative writing (PEP); a paucity of quality professional development about teaching and assessing creative writing (SEP); and issues related to the sustainability of creative approaches to teach writing (SEP; CEP) need to be considered by leaders and teachers in schools. Our literature review advances knowledge about creative writing by revealing two interconnected areas that affect creative writing practices. Findings suggest that a parallel focus on personal conditions and contextual conditions—including structural and cultural—has the potential to improve creative writing in general. Below, we share some implications and recommendations for improved practice by focussing on both (1) personal views about creative writing and (2) the structural and cultural aspects that affect creative writing practices at schools.

Focussing on personal views about creative writing

School leaders and teachers must clearly define what creative writing is, what key skills constitute creative writing.

From our search it was apparent that schools and their educators often do not have a clear idea or indeed a shared idea as to what constitutes creative writing in relation to their own context. Without a well-defined focus for creative writing students may find it difficult to know what is required in classroom tasks and assessment. In addition, when planning for creative writing in school programs, teachers should consider flexible learning opportunities and choice for their students when developing their creative writing skills. Such flexibility should also involve choice of topic, ways of working (e.g. peer collaboration, individual activities etc.), and open discussions led by students in the classroom as shown throughout this paper. It would also be important for leaders and teachers to interrogate current approaches to teaching writing which we argued in the introduction to be formulaic and genre based.

Improve teacher self-efficacy, confidence, and content knowledge in teaching writing

Many of our studies showed that teachers who lacked confidence about writing themselves had less knowledge and skills to teach writing than those that may have participated in projects encouraging ‘teachers as writers’. Further, improved knowledge of grammar (as highlighted in Macken-Horarik’s, 2012 work); talk about writing in the classroom and other spaces (Cremin et al., 2020 ) and the writing process (see Ryan, 2014 ) could assist teachers in becoming more confident to take risks in the classroom with their students. Above all being playful about writing through extended conversations and practices is required.

Focussing on the structural and cultural resources

Improve training and further professional development and learning about teaching and assessing creative writing.

In order for the above personal attributes to be improved, further professional development and learning are required. Many of the papers presented throughout this review demonstrated the powerful impact of immersive professional learning for teachers. Working alongside professional authors, researchers, drama practitioners, visual artists, poets, for example, provided positive opportunities for teachers to learn about writing but also to feel more confident to teach it without imposing strict boundaries on students. We argue for professional development to be both formal and informal including such approaches as coaching and mentoring in the classroom. Demonstrated practice alongside the teacher is also recommended. This, in turn, would address the ongoing issue of creative writing being stifled for students in the classroom context.

Consider sustainability of creative pedagogic approaches and spaces for creative writing in curriculum planning

Many of the studies throughout this paper shared creative approaches to teaching writing but there were concerns that some of these methods may not be sustainable. It is important for school leaders to support the work of teachers in relation to teaching creative writing. We acknowledge that there is increasing uncertainty and scrutiny surrounding teachers’ everyday work (Knight, 2020 ), however, continued engagement in learning about and participating in creative pedagogy for writing is highly recommended. In addition, the studies suggested the provision of appropriate and authentic spaces in which students could creatively write and these often included spaces outside of the normal classroom environment and arts-based approaches implemented in such spaces. Teachers should be encouraged to collaborate and take risks rather than follow predetermined strategies for every lesson. A whole of school practice can be developed with important conversations about the ideologies that inform the school’s approach to writing.

Schools should not stifle creativity in the classroom due to the infiltration of standardised and/or trending approaches to teaching and assessing writing

It is evident that pedagogical approaches to teaching writing have been stifled by more formulaic methods aiming to meet expectations of standardised tests despite other evidence showing the benefits of more productive, engaging, and creative approaches to teaching writing as highlighted above. This can be particularly the case for students from non-dominant backgrounds where writing about cultural and life experiences through innovative practices has been proven to empower their voices (Johnson, 2021 ). The research shows that when students are offered rigid structures of texts, no choice of genres, and indeed word lists, their own decisions about writing are diminished (Ryan & Barton, 2013 ). It has been proven that students’ engagement and motivation to write can increase when they are able to write directly from their own experience or in social groups. It is therefore recommended that school leaders and teachers reconsider their ideologies about writing and explicitly indicate the importance of real-world purposes for writing—not just formulised, quick writing as usually included in external tests—but also those that encourage students’ growth in imagination, creativity, and innovative thought.

This systematic review used a lens of reflexivity to situate writing as a process of active and creative design whereby students make conscious decisions about their writing, with guidance from their teachers. As explained, we see creative writing as writing that engages a reader and, therefore, requires knowledge of authorial voice and appropriate word choice. This involves reflexive decisions relating to personal, structural, and cultural emergent properties. Predominant in the literature was the striking influence of CEPs or the values and expectations ascribed to writing, which in turn influence the strategies and resources (SEPs) and the experiences and motivations of students and teachers in the classroom (PEPs). Writing is about more than a series of perfectly formed sentences in a recognisable structure, which dominates conceptions of writing through high-stakes testing globally. It is about engagement with the expressive self, emergent identities, and relationships to places and people and above all communicating to and/or entertaining a reader. Without quality education in creative writing, society is at risk of losing an art form that is important for cultural practice and expression (Watson, 2016 ).

We do foresee several limitations with such a review, largely related to the positive nature of the studies in relation to creative approaches to teaching writing as well as the relatively small numbers of participants in some of the studies. Most of the studies reported favourably on the approaches taken by teachers to influence student motivation towards writing with limited comments about adverse effects. In terms of contributions, the notion that students need to draw on creative thought and ideas when writing means that teachers and leaders must think about diverse ways to teach writing. We argue, on the basis of the findings, that inquiry-based and reflexive professional learning projects about creativity are crucial for primary classrooms: what creativity means in different contexts and for different writers; how it is enabled; and the decisions and actions that emerge when creative and reflexive design guide our approach to classroom writing. Without quality knowledge and understanding of what creative writing is and how it is taught, we would be at risk of diminishing students’ self-expression and ability to communicate meaning to others in literary forms.

Alhusaini, A. A., & Maker, C. J. (2015). Creativity in students’ writing of open-ended stories across ethnic, gender, and grade groups: An extension study from third to fifth grades. Gifted and Talented International, 30 (1–2), 25–38.

Article Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Children's artistic creativity: Detrimental effects of competition in a field setting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 8 (3), 573–578.

Archer, M. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Archer, M. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity . Cambridge University Press.

Au, W., & Gourd, K. (2013). Asinine assessment: Why high-stakes testing is bad for everyone, including English teachers. English Journal , 14–19.

Baer, J., & McKool, S. (2009). Assessing creativity using the consensual assessment technique . IGI Global.

Barbot, B., Tan, M., Randi, J., Santa-Donato, G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2012). Essential skills for creative writing: Integrating multiple domain-specific perspectives. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7 (3), 209–223.

Brill, F. (2004). Thinking outside the box: Imagination and empathy beyond story writing. Literacy, 38 (2), 83–89.

Christianakis, M. (2011a). Children’s text development: Drawing, pictures, and writing. Research in the Teaching of English, 46 (1), 22–54.

Google Scholar

Christianakis, M. (2011b). Hybrid texts: Fifth graders, rap music, and writing. Urban Education, 46 (5), 1131–1168.

Coles, J. (2017). Planting poetry: Sowing seeds of creativity in a year 5 class changing english. Studies in Culture and Education, 24 (4), 386–398.

Copping, A. (2018). Exploring connections between creative thinking and higher attaining writing. Education, 46 (3), 307–316.

Cremin, T., Myhill, D., Eyres, I., Nash, T., Wilson, A., & Oliver, L. (2020). Teachers as writers: Learning together with others. Literacy, 54 (2), 49–59.

Cress, S. W., & Holm, D. T. (2016). Creative endeavors: Inspiring creativity in a first-grade classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44 (3), 235–243.

DeFauw, D. L. (2018). One school’s yearlong collaboration with a children’s book author. Reading Teacher., 72 (30), 355–367.

Deutsch, L. (2014). Writing from the senses: 59 exercises to ignite creativity and revitalize your writing . Shambhala Publications.

Dobson, T. (2015). Developing a theoretical framework for response: Creative writing as response in the Year 6 primary classroom. English in Education, 49 (3), 252–265.

Dobson, T., & Stephenson, L. (2017). Primary pupils’ creative writing: Enacting identities in a Community of Writers. Literacy, 51 (3), 162–168.

Dobson, T., & Stephenson, L. (2020). Challenging boundaries to cross: Primary teachers exploring drama pedagogy for creative writing with theatre educators in the landscape of performativity. Professional Development in Education, 46 (2), 245–255.

Edwards-Groves, C. (2011). The multimodal writing process: Changing practices in contemporary classrooms. Language and Education, 25 (1), 49–64.

Gibson, R., & Ewing, R. (2020). Transforming the curriculum through the arts . Springer.

Göçen, G. (2019). The effect of creative writing activities on elementary school students’ creative writing achievement, writing attitude and motivation. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15 (3), 1032–1044.

Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 (4), 879.

Grainger, T., Goouch, K., & Lambirth, A. (2005). Creativity and writing: Developing voice and verve in the classroom . Routledge.

Hall, A. H., & Grisham-Brown, J. (2011). Writing development over time: Examining preservice teachers' attitudes and beliefs about writing. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 32 (2), 148–158.

Healey, B. (2019). How children experience creative writing in the classroom. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 42 (3), 184–194.

Johnson, T. (2021). Identity placement in social justice issues through a creative writing curriculum . Unpublished Masters thesis. Hamline University.

Knight, R. (2020). The tensions of innovation: Experiences of teachers during a whole school pedagogical shift. Research Papers in Education, 35 (2), 205–227.

Lee, B. K., & Enciso, P. (2017). The big glamorous monster (or Lady Gaga’s adventures at sea): Improving student writing through dramatic approaches in schools. Journal of Literacy Research, 49 (2), 157–180.

Macken-Horarik, M. (2012). Why school English needs a ‘good enough’ grammatics (and not more grammar). Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education, 19 (2), 179–194.

Mahmood, M. I., Mobeen, M., & Abbas, S. (2020). Effect of high-stakes exams on creative writing skills of ESL learners in Pakistan. Research Journal of Social Sciences and Economics Review, 1 (3), 169–179.

Mendelowitz, B. (2014). Permission to fly: Creating classroom environments of imaginative (im)possibilities. English in Education, 48 (2), 164–183.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6 (7), e1000097.

Polesel, J., Dulfer, N., & Turnbull, M. (2012). The experience of education: The impacts of high stakes testing on school students and their families . The Whitlam Institute.

Portier, C., Friedrich, N., & Stagg Peterson, S. (2019). Play(ful) pedagogical practices for creative collaborative literacy. Reading Teacher, 73 (1), 17–27.

Rumney, P., Buttress, J., & Kuksa, I. (2016). Seeing, doing, writing: The write here project. SAGE Open, 6 (1).

Ryan, M. (2014). Writers as performers: Developing reflexive and creative writing identities. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 13 (3), 130–148.

Ryan, M., & Barton, G. M. (2013). Working towards a ’’thirdspace' in the teaching of writing to middle years students. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years , 21 (3), 71–81.

Ryan, M., & Barton, G. (2014). The spatialized practices of teaching writing in Australian elementary schools: Diverse students shaping discoursal selves. Research in the Teaching of English , 303–329.

Ryan, M., & Daffern, T. (2020). Assessing writing: Teacher-led approaches. Teaching Writing: Effective approaches for the middle years.

Ryan, M., Khosronejad, M., Barton, G., Kervin, L. & Myhill, D. (2021). A reflexive approach to teaching writing: Enablements and constraints in primary school classrooms. Written Communication.

Sears, E. (2012). Painting and poetry: Third graders’ free-form poems inspired by their paintings. Journal of Inquiry and Action in Education, 5 (1), 17–40.

Slavin, E. R., Lake, C., Inns, A., Baye, A., Dachet, D., & Haslam, J. (2019). A quantitative synthesis of research on writing approaches in years 3 to 13 . Education Endowment Foundation.

Smith, H. (2020). The writing experiment: Strategies for innovative creative writing . Routledge.

Southern, A., Elliott, J., & Morley, C. (2020). Third space creative pedagogies: Developing a model of shared CPDL for teachers and artists to support reading and writing in the primary curricula of England and Wales. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 8 (1), 24–31.

Steele, J. (2016). Becoming creative practitioners: Elementary teachers tackle artful approaches to writing instruction. Teaching Education, 27 (1), 1037829. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2015.1037829

Stock, C., & Molloy, K. (2020). Where are the students?: Creative writing in a high-stakes world. Idiom, 56 (3), 19.

Wang, L. (2019). Rethinking the significance of creative writing: A neglected art form behind the language learning curriculum. Cambridge Open-Review Educational Research, 6 , 110–122.

Watson, V. M. (2016). Literacy is a civil write: The art, science, and soul of transformative classrooms. Social Justice Instruction: Empowerment on the Chalkboard , 307–323.

Wyse, D., Jones, R., Bradford, H., & Wolpert, M. A. (2013). Teaching English, language and literacy . Routledge.

Yoo, J., & Carter, D. (2017). Teacher emotion and learning as praxis: Professional development that matters. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42 (3), 38–52.

Download references

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The project that informed this systematic review was on the teaching of writing and funded by the Australian Research Council. The views expressed here are in no way reflective of the ARC.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield, QLD, Australia

Georgina Barton

Australian Catholic University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Maryam Khosronejad & Mary Ryan

Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

Lisa Kervin

Centre for Research in Writing, The University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Debra Myhill

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Georgina Barton .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

Etical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Barton, G., Khosronejad, M., Ryan, M. et al. Teaching creative writing in primary schools: a systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity. Aust. Educ. Res. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00641-9

Download citation

Received : 19 July 2022

Accepted : 26 May 2023

Published : 17 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00641-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Creative writing

- Primary classrooms

- Teaching writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Education, training and skills

- School curriculum

- Primary curriculum, key stage 2

- English (key stage 2)

A review of approaches to assessing writing at the end of primary education

The focus of this paper is on large-scale, primarily summative assessments of writing at the end of primary/elementary education.

Applies to England

Ref: Ofqual/19/6492

PDF , 936 KB , 60 pages

This file may not be suitable for users of assistive technology.

Our research looks at approaches in 15 assessment systems across a number of international jurisdictions, considering the benefits and drawbacks of different approaches. We also review historical approaches to the assessment of writing in England and consider the changes that have taken place since assessments were first introduced in the 1990s.

Assessing writing is a challenging task and we do not claim that a single approach is best. There are a number of complex decisions to be made in the design of any assessment which depend on its purpose and how outcomes will be used. These decisions are often highly context-specific.

Our research also considers innovations in the assessment of writing, including comparative judgement and marking of extended writing by artificial intelligence.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

Primary School

BE BRAVE NOT PERFECT

Writing Assessment

At Stanbridge Primary School, we use the below writing grids to regularly gather evidence of what children can do across a range of writing. The principle behind them is that each year group’s grid features key learning from previous year groups so that all learning is constantly reinforced and re-taught.

This will ensure that children reach the end of Y6 with the knowledge and skills needed to achieve age related expectations, reflecting the new assessment guidelines from The Standards & Testing Agency.

As a picture of the child as a writer is gradually built up across the year, gaps in learning can clearly be seen and most importantly they can be addressed. A large amount of evidence can be gathered from one piece of writing or just one piece of key evidence spotted in a piece.

- Y1 Writing Assessment Grid.pdf

- Y2 Writing Assessment Grid.pdf

- Y3 Writing Assessment Grid.pdf

- Y4 Writing Assessment Grid.pdf

- Y5 Writing Assessment Grid.pdf

- Y6 Writing Assessment Grid.pdf

Maths Assessment

- EYFS - Y2.pdf

- Y3 - Y6.pdf

Unfortunately not the ones with chocolate chips.

Our cookies ensure you get the best experience on our website.

Please make your choice!