ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Global warming.

The causes, effects, and complexities of global warming are important to understand so that we can fight for the health of our planet.

Earth Science, Climatology

Tennessee Power Plant

Ash spews from a coal-fueled power plant in New Johnsonville, Tennessee, United States.

Photograph by Emory Kristof/ National Geographic

Global warming is the long-term warming of the planet’s overall temperature. Though this warming trend has been going on for a long time, its pace has significantly increased in the last hundred years due to the burning of fossil fuels . As the human population has increased, so has the volume of fossil fuels burned. Fossil fuels include coal, oil, and natural gas, and burning them causes what is known as the “greenhouse effect” in Earth’s atmosphere.

The greenhouse effect is when the sun’s rays penetrate the atmosphere, but when that heat is reflected off the surface cannot escape back into space. Gases produced by the burning of fossil fuels prevent the heat from leaving the atmosphere. These greenhouse gasses are carbon dioxide , chlorofluorocarbons, water vapor , methane , and nitrous oxide . The excess heat in the atmosphere has caused the average global temperature to rise overtime, otherwise known as global warming.

Global warming has presented another issue called climate change. Sometimes these phrases are used interchangeably, however, they are different. Climate change refers to changes in weather patterns and growing seasons around the world. It also refers to sea level rise caused by the expansion of warmer seas and melting ice sheets and glaciers . Global warming causes climate change, which poses a serious threat to life on Earth in the forms of widespread flooding and extreme weather. Scientists continue to study global warming and its impact on Earth.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

February 21, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Global Warming 101

Everything you wanted to know about our changing climate but were too afraid to ask.

Temperatures in Beijing rose above 104 degrees Fahrenheit on July 6, 2023.

Jia Tianyong/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

- Share this page block

What is global warming?

What causes global warming, how is global warming linked to extreme weather, what are the other effects of global warming, where does the united states stand in terms of global-warming contributors, is the united states doing anything to prevent global warming, is global warming too big a problem for me to help tackle.

A: Since the Industrial Revolution, the global annual temperature has increased in total by a little more than 1 degree Celsius, or about 2 degrees Fahrenheit. Between 1880—the year that accurate recordkeeping began—and 1980, it rose on average by 0.07 degrees Celsius (0.13 degrees Fahrenheit) every 10 years. Since 1981, however, the rate of increase has more than doubled: For the last 40 years, we’ve seen the global annual temperature rise by 0.18 degrees Celsius, or 0.32 degrees Fahrenheit, per decade.

The result? A planet that has never been hotter . Nine of the 10 warmest years since 1880 have occurred since 2005—and the 5 warmest years on record have all occurred since 2015. Climate change deniers have argued that there has been a “pause” or a “slowdown” in rising global temperatures, but numerous studies, including a 2018 paper published in the journal Environmental Research Letters , have disproved this claim. The impacts of global warming are already harming people around the world.

Now climate scientists have concluded that we must limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040 if we are to avoid a future in which everyday life around the world is marked by its worst, most devastating effects: the extreme droughts, wildfires, floods, tropical storms, and other disasters that we refer to collectively as climate change . These effects are felt by all people in one way or another but are experienced most acutely by the underprivileged, the economically marginalized, and people of color, for whom climate change is often a key driver of poverty, displacement, hunger, and social unrest.

A: Global warming occurs when carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) and other air pollutants collect in the atmosphere and absorb sunlight and solar radiation that have bounced off the earth’s surface. Normally this radiation would escape into space, but these pollutants, which can last for years to centuries in the atmosphere, trap the heat and cause the planet to get hotter. These heat-trapping pollutants—specifically carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, water vapor, and synthetic fluorinated gases—are known as greenhouse gases, and their impact is called the greenhouse effect.

Though natural cycles and fluctuations have caused the earth’s climate to change several times over the last 800,000 years, our current era of global warming is directly attributable to human activity—specifically to our burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, gasoline, and natural gas, which results in the greenhouse effect. In the United States, the largest source of greenhouse gases is transportation (29 percent), followed closely by electricity production (28 percent) and industrial activity (22 percent). Learn about the natural and human causes of climate change .

Curbing dangerous climate change requires very deep cuts in emissions, as well as the use of alternatives to fossil fuels worldwide. The good news is that countries around the globe have formally committed—as part of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement —to lower their emissions by setting new standards and crafting new policies to meet or even exceed those standards. The not-so-good news is that we’re not working fast enough. To avoid the worst impacts of climate change, scientists tell us that we need to reduce global carbon emissions by as much as 40 percent by 2030. For that to happen, the global community must take immediate, concrete steps: to decarbonize electricity generation by equitably transitioning from fossil fuel–based production to renewable energy sources like wind and solar; to electrify our cars and trucks; and to maximize energy efficiency in our buildings, appliances, and industries.

A: Scientists agree that the earth’s rising temperatures are fueling longer and hotter heat waves , more frequent droughts , heavier rainfall , and more powerful hurricanes .

In 2015, for example, scientists concluded that a lengthy drought in California—the state’s worst water shortage in 1,200 years —had been intensified by 15 to 20 percent by global warming. They also said the odds of similar droughts happening in the future had roughly doubled over the past century. And in 2016, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine announced that we can now confidently attribute some extreme weather events, like heat waves, droughts, and heavy precipitation, directly to climate change.

The earth’s ocean temperatures are getting warmer, too—which means that tropical storms can pick up more energy. In other words, global warming has the ability to turn a category 3 storm into a more dangerous category 4 storm. In fact, scientists have found that the frequency of North Atlantic hurricanes has increased since the early 1980s, as has the number of storms that reach categories 4 and 5. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season included a record-breaking 30 tropical storms, 6 major hurricanes, and 13 hurricanes altogether. With increased intensity come increased damage and death. The United States saw an unprecedented 22 weather and climate disasters that caused at least a billion dollars’ worth of damage in 2020, but, according to NOAA, 2017 was the costliest on record and among the deadliest as well: Taken together, that year's tropical storms (including Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria) caused nearly $300 billion in damage and led to more than 3,300 fatalities.

The impacts of global warming are being felt everywhere. Extreme heat waves have caused tens of thousands of deaths around the world in recent years. And in an alarming sign of events to come, Antarctica has lost nearly four trillion metric tons of ice since the 1990s. The rate of loss could speed up if we keep burning fossil fuels at our current pace, some experts say, causing sea levels to rise several meters in the next 50 to 150 years and wreaking havoc on coastal communities worldwide.

A: Each year scientists learn more about the consequences of global warming , and each year we also gain new evidence of its devastating impact on people and the planet. As the heat waves, droughts, and floods associated with climate change become more frequent and more intense, communities suffer and death tolls rise. If we’re unable to reduce our emissions, scientists believe that climate change could lead to the deaths of more than 250,000 people around the globe every year and force 100 million people into poverty by 2030.

Global warming is already taking a toll on the United States. And if we aren’t able to get a handle on our emissions, here’s just a smattering of what we can look forward to:

- Disappearing glaciers, early snowmelt, and severe droughts will cause more dramatic water shortages and continue to increase the risk of wildfires in the American West.

- Rising sea levels will lead to even more coastal flooding on the Eastern Seaboard, especially in Florida, and in other areas such as the Gulf of Mexico.

- Forests, farms, and cities will face troublesome new pests , heat waves, heavy downpours, and increased flooding . All of these can damage or destroy agriculture and fisheries.

- Disruption of habitats such as coral reefs and alpine meadows could drive many plant and animal species to extinction.

- Allergies, asthma, and infectious disease outbreaks will become more common due to increased growth of pollen-producing ragweed , higher levels of air pollution , and the spread of conditions favorable to pathogens and mosquitoes.

Though everyone is affected by climate change, not everyone is affected equally. Indigenous people, people of color, and the economically marginalized are typically hit the hardest. Inequities built into our housing , health care , and labor systems make these communities more vulnerable to the worst impacts of climate change—even though these same communities have done the least to contribute to it.

A: In recent years, China has taken the lead in global-warming pollution , producing about 26 percent of all CO2 emissions. The United States comes in second. Despite making up just 4 percent of the world’s population, our nation produces a sobering 13 percent of all global CO2 emissions—nearly as much as the European Union and India (third and fourth place) combined. And America is still number one, by far, in cumulative emissions over the past 150 years. As a top contributor to global warming, the United States has an obligation to help propel the world to a cleaner, safer, and more equitable future. Our responsibility matters to other countries, and it should matter to us, too.

A: We’ve started. But in order to avoid the worsening effects of climate change, we need to do a lot more—together with other countries—to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and transition to clean energy sources.

Under the administration of President Donald Trump (a man who falsely referred to global warming as a “hoax”), the United States withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement, rolled back or eliminated dozens of clean air protections, and opened up federally managed lands, including culturally sacred national monuments, to fossil fuel development. Although President Biden has pledged to get the country back on track, years of inaction during and before the Trump administration—and our increased understanding of global warming’s serious impacts—mean we must accelerate our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite the lack of cooperation from the Trump administration, local and state governments made great strides during this period through efforts like the American Cities Climate Challenge and ongoing collaborations like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative . Meanwhile, industry and business leaders have been working with the public sector, creating and adopting new clean-energy technologies and increasing energy efficiency in buildings, appliances, and industrial processes.

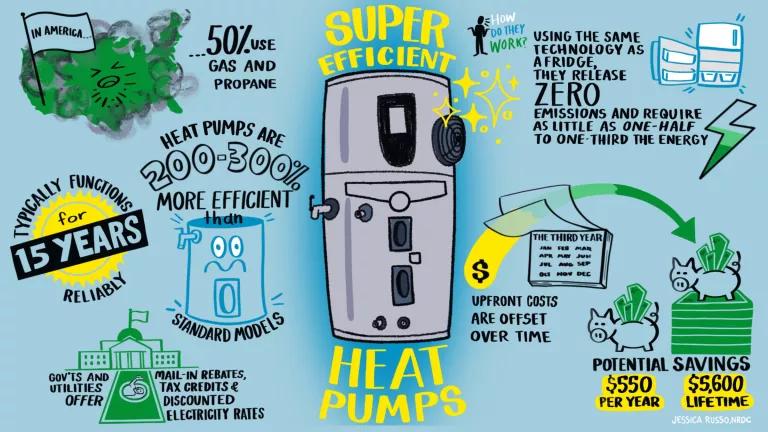

Today the American automotive industry is finding new ways to produce cars and trucks that are more fuel efficient and is committing itself to putting more and more zero-emission electric vehicles on the road. Developers, cities, and community advocates are coming together to make sure that new affordable housing is built with efficiency in mind , reducing energy consumption and lowering electric and heating bills for residents. And renewable energy continues to surge as the costs associated with its production and distribution keep falling. In 2020 renewable energy sources such as wind and solar provided more electricity than coal for the very first time in U.S. history.

President Biden has made action on global warming a high priority. On his first day in office, he recommitted the United States to the Paris Climate Agreement, sending the world community a strong signal that we were determined to join other nations in cutting our carbon pollution to support the shared goal of preventing the average global temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. (Scientists say we must stay below a 2-degree increase to avoid catastrophic climate impacts.) And significantly, the president has assembled a climate team of experts and advocates who have been tasked with pursuing action both abroad and at home while furthering the cause of environmental justice and investing in nature-based solutions.

A: No! While we can’t win the fight without large-scale government action at the national level , we also can’t do it without the help of individuals who are willing to use their voices, hold government and industry leaders to account, and make changes in their daily habits.

Wondering how you can be a part of the fight against global warming? Reduce your own carbon footprint by taking a few easy steps: Make conserving energy a part of your daily routine and your decisions as a consumer. When you shop for new appliances like refrigerators, washers, and dryers, look for products with the government’s ENERGY STAR ® label; they meet a higher standard for energy efficiency than the minimum federal requirements. When you buy a car, look for one with the highest gas mileage and lowest emissions. You can also reduce your emissions by taking public transportation or carpooling when possible.

And while new federal and state standards are a step in the right direction, much more needs to be done. Voice your support of climate-friendly and climate change preparedness policies, and tell your representatives that equitably transitioning from dirty fossil fuels to clean power should be a top priority—because it’s vital to building healthy, more secure communities.

You don’t have to go it alone, either. Movements across the country are showing how climate action can build community , be led by those on the front lines of its impacts, and create a future that’s equitable and just for all .

This story was originally published on March 11, 2016 and has been updated with new information and links.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Related Stories

Liquefied Natural Gas 101

What’s the Most Energy-Efficient Water Heater?

What Do “Better” Batteries Look Like?

When you sign up, you’ll become a member of NRDC’s Activist Network. We will keep you informed with the latest alerts and progress reports.

PRESENTED BY HELLMANN'S

Causes of global warming, explained

Human activity is driving climate change, including global temperature rise.

The average temperature of the Earth is rising at nearly twice the rate it was 50 years ago. This rapid warming trend cannot be explained by natural cycles alone, scientists have concluded. The only way to explain the pattern is to include the effect of greenhouse gases (GHGs) emitted by humans.

Current levels of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide in our atmosphere are higher than at any point over the past 800,000 years , and their ability to trap heat is changing our climate in multiple ways .

IPCC conclusions

To come to a scientific conclusion on climate change and what to do about it, the United Nations in 1988 formed a group called the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change , or IPCC. The IPCC meets every few years to review the latest scientific findings and write a report summarizing all that is known about global warming. Each report represents a consensus, or agreement, among hundreds of leading scientists.

One of the first things the IPCC concluded is that there are several greenhouse gases responsible for warming, and humans emit them in a variety of ways. Most come from the combustion of fossil fuels in cars, buildings, factories, and power plants. The gas responsible for the most warming is carbon dioxide, or CO2. Other contributors include methane released from landfills, natural gas and petroleum industries, and agriculture (especially from the digestive systems of grazing animals); nitrous oxide from fertilizers; gases used for refrigeration and industrial processes; and the loss of forests that would otherwise store CO2.

Gaseous abilities

Different greenhouse gases have very different heat-trapping abilities. Some of them can trap more heat than an equivalent amount of CO2. A molecule of methane doesn't hang around the atmosphere as long as a molecule of carbon dioxide will, but it is at least 84 times more potent over two decades. Nitrous oxide is 264 times more powerful than CO2.

Other gases, such as chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs—which have been banned in much of the world because they also degrade the ozone layer—have heat-trapping potential thousands of times greater than CO2. But because their emissions are much lower than CO2 , none of these gases trap as much heat in the atmosphere as CO2 does.

When those gases that humans are adding to Earth's atmosphere trap heat, it’s called the "greenhouse effect." The gases let light through but then keep much of the heat that radiates from the surface from escaping back into space, like the glass walls of a greenhouse. The more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the more dramatic the effect, and the more warming that happens.

Climate change continues

Despite global efforts to address climate change, including the landmark 2015 Paris climate agreement , carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels continue to rise, hitting record levels in 2018 .

Many people think of global warming and climate change as synonyms, but scientists prefer to use “climate change” when describing the complex shifts now affecting our planet’s weather and climate systems. Climate change encompasses not only rising average temperatures but also extreme weather events, shifting wildlife populations and and habitats, rising seas , and a range of other impacts.

Read next: Global Warming Effects

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- CLIMATE CHANGE

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

- AIR POLLUTION

You May Also Like

Another weapon to fight climate change? Put carbon back where we found it

How global warming is disrupting life on Earth

What is the ozone layer, and why does it matter?

Are there real ways to fight climate change? Yes.

The U.S. ‘warming hole’—a climate anomaly explained

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

UN climate report: It’s ‘now or never’ to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees

Facebook Twitter Print Email

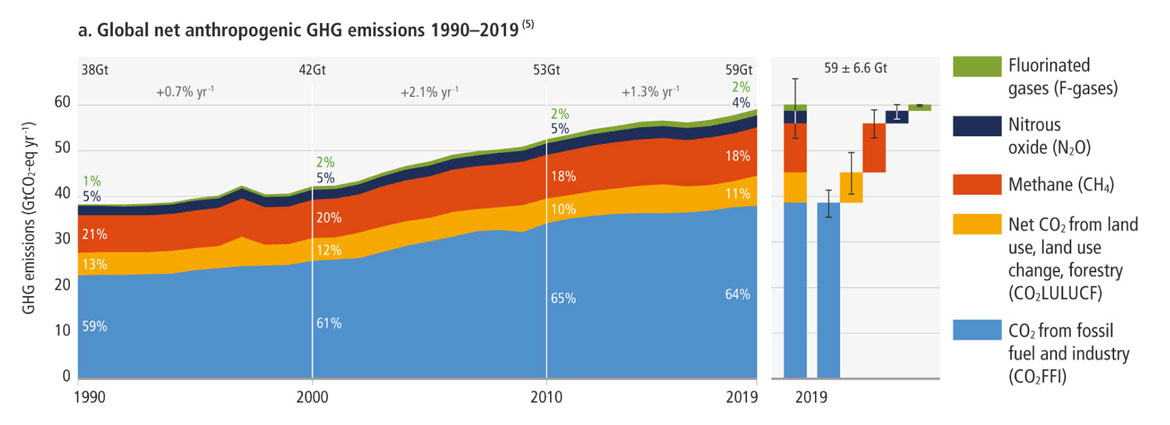

A new flagship UN report on climate change out Monday indicating that harmful carbon emissions from 2010-2019 have never been higher in human history, is proof that the world is on a “fast track” to disaster, António Guterres has warned , with scientists arguing that it’s ‘now or never’ to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.

Reacting to the latest findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC ), the UN Secretary-General insisted that unless governments everywhere reassess their energy policies, the world will be uninhabitable.

#LIVE NOW the press conference to present the #IPCC’s latest #ClimateReport, #ClimateChange 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change, the Working Group III contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. Including a Q&A session with registered media. https://t.co/iIl81zXev7 IPCC IPCC_CH

His comments reflected the IPCC’s insistence that all countries must reduce their fossil fuel use substantially, extend access to electricity, improve energy efficiency and increase the use of alternative fuels, such as hydrogen.

Unless action is taken soon, some major cities will be under water, Mr. Guterres said in a video message, which also forecast “unprecedented heatwaves, terrifying storms, widespread water shortages and the extinction of a million species of plants and animals”.

Horror story

The UN chief added: “This is not fiction or exaggeration. It is what science tells us will result from our current energy policies. We are on a pathway to global warming of more than double the 1.5-degree (Celsius, or 2.7-degrees Fahreinheit) limit ” that was agreed in Paris in 2015.

Providing the scientific proof to back up that damning assessment, the IPCC report – written by hundreds of leading scientists and agreed by 195 countries - noted that greenhouse gas emissions generated by human activity, have increased since 2010 “across all major sectors globally”.

In an op-ed article penned for the Washington Post, Mr. Guterres described the latest IPCC report as "a litany of broken climate promises ", which revealed a "yawning gap between climate pledges, and reality."

He wrote that high-emitting governments and corporations, were not just turning a blind eye, "they are adding fuel to the flames by continuing to invest in climate-choking industries. Scientists warn that we are already perilously close to tipping points that could lead to cascading and irreversible climate effects."

Urban issue

An increasing share of emissions can be attributed to towns and cities , the report’s authors continued, adding just as worryingly, that emissions reductions clawed back in the last decade or so “have been less than emissions increases, from rising global activity levels in industry, energy supply, transport, agriculture and buildings”.

Striking a more positive note - and insisting that it is still possible to halve emissions by 2030 - the IPCC urged governments to ramp up action to curb emissions.

The UN body also welcomed the significant decrease in the cost of renewable energy sources since 2010, by as much as 85 per cent for solar and wind energy, and batteries.

You might also like

- ‘Lifeline’ of renewable energy can steer world out of climate crisis

- 8 reasons not to give up hope - and take climate action

Encouraging climate action

“We are at a crossroads. The decisions we make now can secure a liveable future,” said IPCC Chair Hoesung Lee. “ I am encouraged by climate action being taken in many countries . There are policies, regulations and market instruments that are proving effective. If these are scaled up and applied more widely and equitably, they can support deep emissions reductions and stimulate innovation.”

To limit global warming to around 1.5C (2.7°F), the IPCC report insisted that global greenhouse gas emissions would have to peak “before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43 per cent by 2030”.

Methane would also need to be reduced by about a third, the report’s authors continued, adding that even if this was achieved, it was “almost inevitable that we will temporarily exceed this temperature threshold”, although the world “could return to below it by the end of the century”.

Now or never

“ It’s now or never, if we want to limit global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F); without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible ,” said Jim Skea, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group III, which released the latest report.

Global temperatures will stabilise when carbon dioxide emissions reach net zero. For 1.5C (2.7F), this means achieving net zero carbon dioxide emissions globally in the early 2050s; for 2C (3.6°F), it is in the early 2070s, the IPCC report states.

“This assessment shows that limiting warming to around 2C (3.6F) still requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by a quarter by 2030.”

Policy base

A great deal of importance is attached to IPCC assessments because they provide governments with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies.

They also play a key role in international negotiations to tackle climate change.

Among the sustainable and emissions-busting solutions that are available to governments, the IPCC report emphasised that rethinking how cities and other urban areas function in future could help significantly in mitigating the worst effects of climate change.

“These (reductions) can be achieved through lower energy consumption (such as by creating compact, walkable cities), electrification of transport in combination with low-emission energy sources, and enhanced carbon uptake and storage using nature,” the report suggested. “There are options for established, rapidly growing and new cities,” it said.

Echoing that message, IPCC Working Group III Co-Chair, Priyadarshi Shukla, insisted that “the right policies, infrastructure and technology…to enable changes to our lifestyles and behaviour, can result in a 40 to 70 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. “The evidence also shows that these lifestyle changes can improve our health and wellbeing.”

- climate action

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

Search the United Nations

- What Is Climate Change

- Myth Busters

- Renewable Energy

- Finance & Justice

- Initiatives

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Paris Agreement

- Climate Ambition Summit 2023

- Climate Conferences

- Press Material

- Communications Tips

Causes and Effects of Climate Change

Fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – are by far the largest contributor to global climate change, accounting for over 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90 per cent of all carbon dioxide emissions. As greenhouse gas emissions blanket the Earth, they trap the sun’s heat. This leads to global warming and climate change. The world is now warming faster than at any point in recorded history. Warmer temperatures over time are changing weather patterns and disrupting the usual balance of nature. This poses many risks to human beings and all other forms of life on Earth.

Sacred plant helps forge a climate-friendly future in Paraguay

El Niño and climate crisis raise drought fears in Madagascar

The El Niño climate pattern, a naturally occurring phenomenon, can significantly disrupt global weather systems, but the human-made climate emergency is exacerbating the destructive effects.

“Verified for Climate” champions: Communicating science and solutions

Gustavo Figueirôa, biologist and communications director at SOS Pantanal, and Habiba Abdulrahman, eco-fashion educator, introduce themselves as champions for “Verified for Climate,” a joint initiative of the United Nations and Purpose to stand up to climate disinformation and put an end to the narratives of denialism, doomism, and delay.

Facts and figures

- What is climate change?

- Causes and effects

- Myth busters

Cutting emissions

- Explaining net zero

- High-level expert group on net zero

- Checklists for credibility of net-zero pledges

- Greenwashing

- What you can do

Clean energy

- Renewable energy – key to a safer future

- What is renewable energy

- Five ways to speed up the energy transition

- Why invest in renewable energy

- Clean energy stories

- A just transition

Adapting to climate change

- Climate adaptation

- Early warnings for all

- Youth voices

Financing climate action

- Finance and justice

- Loss and damage

- $100 billion commitment

- Why finance climate action

- Biodiversity

- Human Security

International cooperation

- What are Nationally Determined Contributions

- Acceleration Agenda

- Climate Ambition Summit

- Climate conferences (COPs)

- Youth Advisory Group

- Action initiatives

- Secretary-General’s speeches

- Press material

- Fact sheets

- Communications tips

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Talking about Climate Change and Global Warming

Contributed equally to this work with: Maurice Lineman, Yuno Do

Affiliation College of Natural Sciences, Department of Biological Sciences, Pusan National University, Busan, South Korea

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Maurice Lineman,

- Yuno Do,

- Ji Yoon Kim,

- Gea-Jae Joo

- Published: September 29, 2015

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138996

- Reader Comments

The increasing prevalence of social networks provides researchers greater opportunities to evaluate and assess changes in public opinion and public sentiment towards issues of social consequence. Using trend and sentiment analysis is one method whereby researchers can identify changes in public perception that can be used to enhance the development of a social consciousness towards a specific public interest. The following study assessed Relative search volume (RSV) patterns for global warming (GW) and Climate change (CC) to determine public knowledge and awareness of these terms. In conjunction with this, the researchers looked at the sentiment connected to these terms in social media networks. It was found that there was a relationship between the awareness of the information and the amount of publicity generated around the terminology. Furthermore, the primary driver for the increase in awareness was an increase in publicity in either a positive or a negative light. Sentiment analysis further confirmed that the primary emotive connections to the words were derived from the original context in which the word was framed. Thus having awareness or knowledge of a topic is strongly related to its public exposure in the media, and the emotional context of this relationship is dependent on the context in which the relationship was originally established. This has value in fields like conservation, law enforcement, or other fields where the practice can and often does have two very strong emotive responses based on the context of the problems being examined.

Citation: Lineman M, Do Y, Kim JY, Joo G-J (2015) Talking about Climate Change and Global Warming. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138996. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138996

Editor: Hayley J. Fowler, Newcastle University, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: August 18, 2014; Accepted: September 8, 2015; Published: September 29, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Lineman et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding: This study was financially supported by the 2015 Post-Doc Development Program of Pusan National University.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Identifying trends in the population, used to be a long and drawn out process utilizing surveys and polls and then collating the data to determine what is currently most popular with the population [ 1 , 2 ]. This is true for everything that was of merit to the political organizations present, regarding any issue of political or public interest.

Recently, the use of the two terms ‘Climate Change’ and ‘Global Warming’ have become very visible to the public and their understanding of what is happening with respect to the climate [ 3 ]. The public response to all of the news and publicity about climate has been a search for understanding and comprehension, leading to support or disbelief. The two terms while having similarity in meaning are used in slightly different semantic contexts. The press in order to expand their news readership/viewer lists has chosen to use this ambiguity to their favor in providing news to the public [ 4 ]. Within the news releases, the expression ‘due to climate change’ has been used to explain phenomological causality.

These two terms “global warming–(GW)” and “climate change–(CC)” both play a role in how the public at large views the natural world and the changes occurring in it. They are used interactively by the news agencies, without a thought towards their actual meaning [ 3 , 4 ]. Therefore, the public in trying to identify changes in the news and their understanding of those changes looks for the meaning of those terms online. The extent of their knowledge can be examined by assessing the use of the terms in online search queries. Information searches using the internet are increasing, and therefore can indicate public or individual interest.

Internet search queries can be tracked using a variety of analytic engines that are independent of, or embedded into, the respective search engines (google trend, naver analytics) and are used to determine the popularity of a topic in terms of internet searches [ 5 ]. The trend engines will look for selected keywords from searches, keywords chosen for their relevance to the field or the query being performed.

The process of using social media to obtain information on public opinion is a practice that has been utilized with increasing frequency in modern research for subjects ranging from politics [ 6 , 7 ] to linguistics [ 8 – 10 ] complex systems [ 11 , 12 ] to environment [ 13 ]. This variety of research belies the flexibility of the approach, the large availability of data availability for mining in order to formulate a response to public opinion regarding the subject being assessed. In modern society understanding how the public responds regarding complex issues of societal importance [ 12 ].

While the two causally connected terms GW and CC are used interchangeably, they describe entirely different physical phenomena [ 14 ]. These two terms therefore can be used to determine how people understand the parallel concepts, especially if they are used as internet search query terms in trend analysis. However, searching the internet falls into two patterns, searches for work or for personal interest, neither of which can be determined from the trend engines. The By following the searches, it is possible to determine the range of public interest in the two terms, based on the respective volumes of the search queries. Previously in order to mine public opinion on a subject, government agencies had to revert to polling and surveys, which while being effective did not cover a very large component of the population [ 15 – 17 ].

Google trend data is one method of measuring popularity of a subject within the population. Individuals searching for a topic use search keywords to obtain the desired information [ 5 , 18 ]. These keywords are topic sensitive, and therefore indicate the level of knowledge regarding the searched topic. The two primary word phrases here “climate change” and “global warming” are unilateral terms that indicate a level of awareness about the issue which is indicative of the individuals interest in that subject [ 5 , 19 , 20 ]. Google trend data relates how often a term is searched, that is the frequency of a search term can be identified from the results of the Google® trend analysis. While frequency is not a direct measure of popularity, it does indicate if a search term is common or uncommon and the value of that term to the public at large. The relationship between frequency and popularity lies in the volume of searches by a large number of individuals over specific time duration. Therefore, by identifying the number of searches during a specific period, it is possible to come to a proximate understanding of how popular or common a term is for the general population [ 21 ]. However, the use of trend data is more appropriately used to identify awareness of an issue rather than its popularity.

This brings us to sentiment analysis. Part of the connection between the search and the populations’ awareness of an issue can be measured using how they refer to the subject in question. This sentiment, is found in different forms of social media, or social networking sites sites i.e. twitter®, Facebook®, linked in® and personal blogs [ 7 , 22 – 24 ]. Thus, the original information, which was found on the internet, becomes influenced by personal attitudes and opinions [ 25 ]and then redistributed throughout the internet, accessible to anyone who has an internet connection and the desire to search. This behavior affects the information that now provides the opportunity to assess public sentiment regarding the prevailing attitudes regarding environmental issues [ 26 , 27 ]. To assess this we used Google® and Twitter® data to understand public concerns related to climate change and global warming. Google trend was used to trace changes in interest between the two phenomena. Tweets (comments made on Twitter®) were analyzed to identify negative or positive emotional responses.

Comparatively, twitter data is more indicative of how people refer to topics of interest [ 28 – 31 ], in a manner that is very linguistically restricted. As well, twitter is used as a platform for verbal expression of emotional responses. Due to the restrictions on tweet size (each tweet can only be 140 characters in length), it is necessary to be more direct in dealing with topics of interest to the tweeter. Therefore, the tweets are linguistically more emotionally charged and can be used to define a level of emotional response by the tweeter.

The choice of target words for the tweets and for the Google trend searches were the specific topic phrases [ 32 , 33 ]. These were chosen because of the descriptive nature of the phrases. Scientific literature is very specific in its use and therefore has very definitive meanings. The appropriation of these words by the population as a method for describing their response to the variation in the environment provides the basis for the choice as target words for the study. The classification of the words as being positive versus negative lies in the direction provided by Frank Lutz. This politicization of a scientific word as a means of directing public awareness, means the prescription of one phrase (climate change) as being more positive than the other (global warming).

Global warming is defined as the long-term trend of increasing average global temperatures; alternatively, climate change is defined as a change in global or regional climate patterns, in particular a change apparent from the mid to late 20 th century onwards and attributed to the increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide arising from the use of fossil fuels. Therefore, the search keywords were chosen based on their scientific value and their public visibility. What is important about the choice of these search terms is that due to their scientific use, they describe a distinctly identifiable state. The more specific these words are, the less risk of the algorithm misinterpreting the keyword and thus having the results misinterpreted [ 34 – 36 ].

The purpose of the following study was to identify trends within search parameters for two specific sets of trend queries. The second purpose of the study was to identify how the public responds emotionally to those same queries. Finally, the purpose of the study was to determine if the two had any connections.

Data Collection

Public awareness of the terms climate change and global warming was identified using Google Trends (google.com/trends) and public databases of Google queries [ 37 ]. To specify the exact searches we used the two terms ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ as query phrases. Queries were normalized using relative search volume (RSV) to the period with the highest proportion of searches going to the focal terms (i.e. RSV = 100 is the period with the highest proportion for queries within a category and RSV = 50 when 50% of that is the highest search proportion). Two assumptions were necessary for this study. The first is, of the two terms, climate change and global warming, that which draws more search results is considered more interesting to the general population. The second assumption is that changes in keyword search patterns are indicators of the use of different forms of terminology used by the public. To analyze sentiments related to climate change and global warming, tweets containing acronyms for climate change and global warming were collected from Twitter API for the period from October 12 to December 12, 2013. A total of 21,182 and 26,462 tweets referencing the terms climate change and global warming were collected respectively. When duplicated tweets were identified, they were removed from the analysis. The remaining tweets totaled 8,465 (climate change) and 8,263 (global warming) were compiled for the sentiment analysis.

Data Analysis

In Twitter® comments are emotionally loaded, due to their textually shortened nature. Sentiment analysis, which is in effect opinion mining, is how opinions in texts are assessed, along with how they are expressed in terms of positive, neutral or negative content [ 36 ]. Nasukawa and Yi [ 10 ]state that sentiment analysis identifies statements of sentiment and classifies those statements based on their polarity and strength along with their relationship to the topic.

Sentiment analysis was conducted using Semantria® software ( www.semantria.com ), which is available as an MS Excel spreadsheet application plugin. The plugin is broken into parts of speech (POS), the algorithm within the plugin then identifies sentiment-laden phrases and then scores them from -10 to 10 on a logarithmic scale, and finally the scores for each POS are tabulated to identify the final score for each phrase. The tweets are then via statistical inferences tagged with a numerical value from -2 to 2 and given a polarity, which is classified as positive, neutral or negative [ 36 ]. Semantria®, the program utilized for this study, has been used since 2011 to perform sentiment analyses [ 7 , 22 ].

For the analysis, an identity column was added to the dataset to enable analysis of individual tweets with respect to sentiment. A basic sentiment analysis was conducted on the dataset using the Semantria® plugin. The plugin uses a cloud based corpus of words tagged with sentimental connotations to analyze the dataset. Through statistical inference, each tweet is tagged with a sentiment value from -2 to +2 and a polarity of (i) negative, (ii) neutral, or (iii) positive. Positive nature increases with increasing positive sentiment. The nature of the language POS assignation is dependent upon the algorithmic classification parameters defined by the Semantria® program. Determining polarity for each POS is achieved using the relationship between the words as well as the words themselves. By assigning negative values to specific negative phrases, it limits the use of non-specific negation processes in language; however, the program has been trained to assess non-specific linguistic negations in context.

A tweet term frequency dictionary was computed using the N-gram method from the corpus of climate change and global warming [ 38 ]. We used a combination of unigrams and bigrams, which has been reported to be effective [ 39 ]. Before using the N-gram method, typological symbols were removed using the open source code editor (i.e. Notepad) or Microsoft Words’ “Replace” function.

Differences in RSV’s for the terms global warming and climate change for the investigation period were identified using a paired t-test. Pettitt and Mann-Kendall tests were used to identify changes in distribution, averages and the presence of trends within the weekly RSV’s. The Pettitt and MK tests, which assume a stepwise shift in the mean (a break point) and are sensitive to breaks in the middle of a time series, were applied to test for homogeneity in the data [ 40 ]. Temporal trends within the time series were analyzed with Spearman’s non-parametric correlation analysis. A paired t-test and Spearman’s non-parametric correlation analysis were conducted using SPSS software (version 17.0 SPSS In corp. Chicago IL) and Pettitt and MK tests were conducted using XLSTAT (version 7.0).

To determine the accuracy and reliability of the Sentiment analysis, a Pearson’s chi-square analysis was performed. This test identifies the difference ratio for each emotional response group, and then compares them to determine reliance and probability of interactions between the variables, in this case the terms global warming and climate change.

According to Google trend ( Fig 1 ) from 2004–2014, people searched for the term global warming (n = 8,464; mean ± S.D = 25.33 ± 2.05) more frequently than climate change (n = 8,283; mean ± S.D. = 7.97±0.74). Although the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its Fourth Assessment Report in 2007 and was awarded the Nobel Prize, interest in the term global warming as used in internet searches has decreased significantly since 2010 (K = 51493, t = 2010-May-23, P<0.001). Further the change in RSV also been indicative of the decreased pattern (Kendall’s tau = -0.336, S = -44563, P<0.001). The use of the term “climate change” has risen marginally since 2006 (K = 38681, t = 2006-Oct-08, P<0.001), as indicated by a slight increase (Kendall’s tau = -0.07, S = 9068, P<0.001). These findings show that the difference in usage of the two terms climate change and global warming has recently been reduced.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138996.g001

The sentiment analysis of tweets ( Fig 2 ) shows that people felt more negative about the term global warming (sentiment index = -0.21±0.34) than climate change (-0.068±0.36). Global warming tweets reflecting negative sentiments via descriptions such as, “bad, fail, crazy, afraid and catastrophe,” represented 52.1% of the total number of tweets. As an example, the tweet, “Supposed to snow here in the a.m.! OMG. So sick of already, but Saturday says 57 WTF!” had the lowest score at -1.8. Another observation was that 40.7% of tweets, including “agree, recommend, rescue, hope, and contribute,” were regarded as neutral. While 7.2% of tweets conveyed positive messages such as, “good, accept, interesting, and truth.” One positive global warming tweet, read, “So if we didn’t have global warming, would all this rain be snow!”. The results from the Pearson’s chi-square analysis showed that the relationship between the variables was significant (Pearson’s chi-square –763.98, d.f. = 2, P<0.001). Negative climate change tweets represented 33.1% of the total while neutral tweets totaled 49.8%, while positive climate change tweets totaled 17.1%.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138996.g002

Understandably, global warming and climate change are the terms used most frequently to describe each phenomenon, respectively, as revealed by the N-gram analysis ( Table 1 ). When people tweeted about global warming, they repeatedly used associated such as, “ice, snow, Arctic, and sea.” In contrast, tweets referring to climate change commonly used, “report, IPCC, world, science, environment, and scientist.” People seem to think that climate change as a phenomenon is revealed by scientific investigation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138996.t001

Internet searches are one way of understanding the popularity of an idea or meme within the public at large. Within that frame of reference, the public looks at these two terms global warming and climate change and their awareness of the roles of the two phenomena [ 41 ]. From 2004 to 2008, the search volumes for the term global warming far exceeded the term climate change. The range for the term global warming in Relative search volumes (RSV) was more than double that of climate change in this period ( Fig 1 ). From 2008 on the RSV’s began to steadily decrease until in 2014 when the RSV’s for the term global warming were nearly identical to those for the term climate change. From 2008 there was an increase in the RSVs for CC until 2010 at which point the RSVs also began to decline for the term climate change. The decline in the term climate change for the most part paralleled that of the term global warming from 2010 on to the present.

While we are seeing the increases and decreases in RSVs for both the terms global warming and climate change, the most notable changes occur when the gap between the terms was the greatest, from 2008 through to 2010. During this period, there was a very large gap found between the RSVs for the terms global warming and climate change; however, searches for the term climate change was increasing while searches for the tem global warming were decreasing. The counter movement of the RSV’s for the two terms shows that there is a trend happening with respect to term recognition. At this point, there was an increase in the use of the CC term while there was a corresponding decrease in the use of the GW term. The change in the use of the term could have been due to changes in the publicity of the respective terms, since at this point, the CC term was being used more visibly in the media, and therefore the CC term was showing up in headlines and the press, resulting in a larger number of searches for the CC term. Correspondingly, the decrease in the use of the GW term is likely due to the changes in how the term was perceived by the public. The public press determines how a term is used, since they are the body that consistently utilizes a term throughout its visible life. The two terms, regardless of how they differ in meaning, are used with purpose in a scientific context, yet the public at large lacks this definition and therefore has no knowledge of the variations in the terms themselves [ 42 ]. Therefore, when searching for a term, the public may very well, choose the search term that they are more comfortable with, resulting in a search bias, since they do not know the scientific use of the term.

The increase in the use of the CC term, could be a direct result of the release of the fourth assessment report for the IPCC in 2007 [ 43 ]. The publicity related to the release of this document, which was preceded by the release of the Al Gore produced documentary “An Inconvenient Truth”, both of which were followed by the selection by the Nobel committee of Al Gore and the IPCC scientists for the Nobel Prize in 2007 [ 43 ]. These three acts individually may not have created the increased media presence of the CC term; however, at the time the three events pushed the CC term and increased its exposure to the public which further drove the public to push for positive environmental change at the political level [ 44 , 45 ]. This could very well have resulted in the increases in RSV’s for the CC term. This point is more likely to depict accurately the situation, since in 2010 the use of the two terms decline at almost the same rate, with nearly the same patterns.

Thus with respect to trend analysis, what is interesting is that RSVs are paralleling the press for specific environmental events that have predetermined value according to the press. The press in increasing the visibility of the term may drive the increases in the RSV’s for that term. Prior to 2007, the press was using the GW term indiscriminately whenever issues affecting the global climate arose; however, after the movie, the report and then the Nobel prize the terminology used by the press switched and the CC term became the word du jour. This increased the visibility of the word to the public, thereby it may be that increasing public awareness of the word, but not necessarily its import, is the source for the increases in RSV’s between 2008 and 2010.

The decline in the RSV’s then is a product of the lack of publicity about the issue. As the terms become more familiar, there would be less necessity to drive the term publicly into the spotlight; however, occasionally events/situations arise that refocus the issue creating a resurgence in the terms even though they have reached their peak visibility between 2008 and 2010.

Since these terms have such an impact on the daily lives of the public via local regional national and global weather it is understandable that they have an emotional component to them [ 46 ]. Every country has its jokes about the weather, where they come up with cliché’s about the weather (i.e. if you don’t like the weather wait 10minutes) that often show their discord and disjunction with natural climatological patterns [ 47 ]. Furthermore, some sectors of society (farmers) have a direct relationship with the climate and their means of living; bad weather is equal to bad harvests, which means less money. To understand how society represents this love hate relationship with the weather, the twitter analysis was performed. Twitter, a data restricted social network system, has a limited character count to relay information about any topic the sender chooses to relate. These tweets can be used to assess the sentiment of the sender towards a certain topic. As stated previously, the sentiment is defined by the language of the tweet within the twitter system. Sentiment analysis showed that the two terms differed greatly. Based on the predefined algorithm for the sentiment analysis, certain language components carried a positive sentiment, while others carried a negative sentiment. Tweets about GW and CC were subdivided based on their positive, neutral and negative connotations within the tweet network. These emotions regardless of their character still play a role in how humans interacts with surroundings including other humans [ 48 , 49 ] As seen in Fig 2 the different terms had similar distributions, although with different ranges in the values. Global warming showed a much smaller positive tweet value than did climate change. Correspondent to this the respective percentage of positive sentiments for CC was more than double that of GW. Comparatively, the neutral percentiles were more similar for each term with a small difference. However, the negative sentiments for the two terms again showed a greater disparity, with negative statements about GW nearly double those of climate change.

These differences show that there is a perceptive difference in how the public relates to the two terms Global Warming and Climate Change [ 50 , 51 ]. Climate change is shown in a more positive light than global warming simply based on the tweets produced by the public. The difference in how people perceive climate change and global warming is possibly due to the press, personal understanding of the terms, or level of education. While this in itself is indefinable, since by nature tweets are linguistically restrictive, the thing to take from it is that there is a measurable difference in how individuals respond to climatological changes that they are experiencing daily. These changes have a describable effect on how the population is responding to the publicity surrounding the two terms to the point where it can be used to manipulate governmental policy [ 52 ].

Sentiment analysis is a tool that can be used to determine how the population feels about a topic; however, the nature of the algorithm makes it hard to effectively determine how this is being assessed. For the current study, the sentiment analysis showed that there was a greater negative association with the term global warming than with the term climate change. This difference, which while being an expression of individual like or dislike at the time the tweet was created, denotes that the two terms were either not understood in their true form, or that individuals may have a greater familiarity with one term over the other, which may be due to a longer exposure to the term (GW) or the negative press associated with the term (GW).

Conclusions

Trend analysis identified that the public is aware of the terminology used to describe climatological variation. The terminology showed changes in use over time with global warming starting as the more well-known term, and then its use decreased over time. At the same time, the more definitive term climate change had less exposure early on; however, with the increase of press exposure, the public became increasingly aware of the term and its more accurate definition. This increase appeared to be correspondent with the increasing publicity around three very powerful press exposure events (a documentary, a scientific report release and a Nobel Prize). The more the term was used the more people came to use it, this included searches on the internet.

Comparatively sentiment analysis showed that the two terms had differential expressions in the population. With climate change being seen in a more positive frame than global warming. The use of sentiment analysis as a tool to evaluate how the population is responding to a feature is an important tool. However, it is a tool that measures, it does not define.

Social network systems and internet searches are effective tools in identifying changes in both public awareness and public perception of an issue. However, in and of itself, these are bell ringers they can be used to determine the importance of an issue, but not the rationale behind the why it is important. This is an important fact to remember when using analytical tools that evaluate social network systems and their use by the public.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the 2015 Post-Doc. Development Program of Pusan National University

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: YD GJJ. Performed the experiments: ML YD. Analyzed the data: ML YD. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: JK YD. Wrote the paper: ML YD GJJ.

- 1. Motteux NMG. Evaluating people-environment relationships: developing appropriate research methodologies for sustainable management and 2003.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 7. Abeywardena IS. Public opinion on OER and MOCC: a sentiment analysis of twitter data. 2014.

- 8. Choi Y, Cardie C, editors. Learning with compositional semantics as structural inference for subsentential sentiment analysis. Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2008: Association for Computational Linguistics.

- 9. Wiegand M, Balahur A, Roth B, Klakow D, Montoyo A, editors. A survey on the role of negation in sentiment analysis. Proceedings of the workshop on negation and speculation in natural language processing; 2010: Association for Computational Linguistics.

- 10. Nasukawa T, Yi J, editors. Sentiment analysis: Capturing favorability using natural language processing. Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on Knowledge capture; 2003: ACM.

- 13. De Longueville B, Smith RS, Luraschi G, editors. Omg, from here, i can see the flames!: a use case of mining location based social networks to acquire spatio-temporal data on forest fires. Proceedings of the 2009 international workshop on location based social networks; 2009: ACM.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 23. Wang X, Wei F, Liu X, Zhou M, Zhang M, editors. Topic sentiment analysis in twitter: a graph-based hashtag sentiment classification approach. Proceedings of the 20th ACM international conference on Information and knowledge management; 2011: ACM.

- 27. Zhao D, Rosson MB, editors. How and why people Twitter: the role that micro-blogging plays in informal communication at work. Proceedings of the ACM 2009 international conference on Supporting group work; 2009: ACM.

- 30. Phelan O, McCarthy K, Smyth B, editors. Using twitter to recommend real-time topical news. Proceedings of the third ACM conference on Recommender systems; 2009: ACM.

- 31. Bruns A, Burgess J. # ausvotes: How Twitter covered the 2010 Australian federal election. 2011.

- 32. Pinkerton B, editor Finding what people want: Experiences with the WebCrawler. Proceedings of the Second International World Wide Web Conference; 1994: Chicago.

- 36. Lawrence L. Reliability of Sentiment Mining Tools: A comparison of Semantria and Social Mention. 2014.

- 43. Neverla I, editor The IPCC-reports 1990–2007 in the media. A case-study on the dialectics between journalism and natural sciences. ICA-Conference, Global Communication and Social Change, Montreal: International Communications Association; 2008.

- 44. Giddens A. The politics of climate change. Cambridge, UK. 2009.

- 46. Doherty TJ, Clayton S. The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. 2011.

- 51. Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation: Oxford University Press; 1991.

Climate Change: Evidence and Causes: Update 2020 (2020)

Chapter: conclusion, c onclusion.

This document explains that there are well-understood physical mechanisms by which changes in the amounts of greenhouse gases cause climate changes. It discusses the evidence that the concentrations of these gases in the atmosphere have increased and are still increasing rapidly, that climate change is occurring, and that most of the recent change is almost certainly due to emissions of greenhouse gases caused by human activities. Further climate change is inevitable; if emissions of greenhouse gases continue unabated, future changes will substantially exceed those that have occurred so far. There remains a range of estimates of the magnitude and regional expression of future change, but increases in the extremes of climate that can adversely affect natural ecosystems and human activities and infrastructure are expected.

Citizens and governments can choose among several options (or a mixture of those options) in response to this information: they can change their pattern of energy production and usage in order to limit emissions of greenhouse gases and hence the magnitude of climate changes; they can wait for changes to occur and accept the losses, damage, and suffering that arise; they can adapt to actual and expected changes as much as possible; or they can seek as yet unproven “geoengineering” solutions to counteract some of the climate changes that would otherwise occur. Each of these options has risks, attractions and costs, and what is actually done may be a mixture of these different options. Different nations and communities will vary in their vulnerability and their capacity to adapt. There is an important debate to be had about choices among these options, to decide what is best for each group or nation, and most importantly for the global population as a whole. The options have to be discussed at a global scale because in many cases those communities that are most vulnerable control few of the emissions, either past or future. Our description of the science of climate change, with both its facts and its uncertainties, is offered as a basis to inform that policy debate.

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following individuals served as the primary writing team for the 2014 and 2020 editions of this document:

- Eric Wolff FRS, (UK lead), University of Cambridge

- Inez Fung (NAS, US lead), University of California, Berkeley

- Brian Hoskins FRS, Grantham Institute for Climate Change

- John F.B. Mitchell FRS, UK Met Office

- Tim Palmer FRS, University of Oxford

- Benjamin Santer (NAS), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- John Shepherd FRS, University of Southampton

- Keith Shine FRS, University of Reading.

- Susan Solomon (NAS), Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Kevin Trenberth, National Center for Atmospheric Research

- John Walsh, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

- Don Wuebbles, University of Illinois

Staff support for the 2020 revision was provided by Richard Walker, Amanda Purcell, Nancy Huddleston, and Michael Hudson. We offer special thanks to Rebecca Lindsey and NOAA Climate.gov for providing data and figure updates.

The following individuals served as reviewers of the 2014 document in accordance with procedures approved by the Royal Society and the National Academy of Sciences:

- Richard Alley (NAS), Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University

- Alec Broers FRS, Former President of the Royal Academy of Engineering

- Harry Elderfield FRS, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge

- Joanna Haigh FRS, Professor of Atmospheric Physics, Imperial College London

- Isaac Held (NAS), NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory

- John Kutzbach (NAS), Center for Climatic Research, University of Wisconsin

- Jerry Meehl, Senior Scientist, National Center for Atmospheric Research

- John Pendry FRS, Imperial College London

- John Pyle FRS, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge

- Gavin Schmidt, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- Emily Shuckburgh, British Antarctic Survey

- Gabrielle Walker, Journalist

- Andrew Watson FRS, University of East Anglia

The Support for the 2014 Edition was provided by NAS Endowment Funds. We offer sincere thanks to the Ralph J. and Carol M. Cicerone Endowment for NAS Missions for supporting the production of this 2020 Edition.

F OR FURTHER READING

For more detailed discussion of the topics addressed in this document (including references to the underlying original research), see:

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2019: Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [ https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc ]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), 2019: Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25259 ]

- Royal Society, 2018: Greenhouse gas removal [ https://raeng.org.uk/greenhousegasremoval ]

- U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), 2018: Fourth National Climate Assessment Volume II: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States [ https://nca2018.globalchange.gov ]

- IPCC, 2018: Global Warming of 1.5°C [ https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15 ]

- USGCRP, 2017: Fourth National Climate Assessment Volume I: Climate Science Special Reports [ https://science2017.globalchange.gov ]

- NASEM, 2016: Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21852 ]

- IPCC, 2013: Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) Working Group 1. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis [ https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1 ]

- NRC, 2013: Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating Surprises [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18373 ]

- NRC, 2011: Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and Impacts Over Decades to Millennia [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12877 ]

- Royal Society 2010: Climate Change: A Summary of the Science [ https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2010/climate-change-summary-science ]

- NRC, 2010: America’s Climate Choices: Advancing the Science of Climate Change [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12782 ]

Much of the original data underlying the scientific findings discussed here are available at:

- https://data.ucar.edu/

- https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu

- https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu

- https://ess-dive.lbl.gov/

- https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/

- https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/

- http://scrippsco2.ucsd.edu

- http://hahana.soest.hawaii.edu/hot/

Climate change is one of the defining issues of our time. It is now more certain than ever, based on many lines of evidence, that humans are changing Earth's climate. The Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences, with their similar missions to promote the use of science to benefit society and to inform critical policy debates, produced the original Climate Change: Evidence and Causes in 2014. It was written and reviewed by a UK-US team of leading climate scientists. This new edition, prepared by the same author team, has been updated with the most recent climate data and scientific analyses, all of which reinforce our understanding of human-caused climate change.

Scientific information is a vital component for society to make informed decisions about how to reduce the magnitude of climate change and how to adapt to its impacts. This booklet serves as a key reference document for decision makers, policy makers, educators, and others seeking authoritative answers about the current state of climate-change science.

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Climate change articles within Scientific Reports

Article 02 April 2024 | Open Access

Potential distribution of Biscogniauxia mediterranea and Obolarina persica causal agents of oak charcoal disease in Iran’s Zagros forests

- Meysam BakhshiGanje

- , Shirin Mahmoodi

- & Mansoureh Mirabolfathy

Current and projected flood exposure for Alaska coastal communities

- Richard M. Buzard

- , Christopher V. Maio

- & Benjamin M. Jones

Article 28 March 2024 | Open Access

Spatiotemporal link between El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), extreme heat, and thermal stress in the Asia–Pacific region

- Jakob Eggeling

- , Chuansi Gao

- & Amir Sapkota

Article 27 March 2024 | Open Access

Source attribution of carbonaceous fraction of particulate matter in the urban atmosphere based on chemical and carbon isotope composition

- Alicja Skiba

- , Katarzyna Styszko

- & Kazimierz Różański

Article 25 March 2024 | Open Access

Warmer autumns and winters could reduce honey bee overwintering survival with potential risks for pollination services

- Kirti Rajagopalan

- , Gloria DeGrandi-Hoffman

- & Tobin D. Northfield

Article 21 March 2024 | Open Access

The value of marsh restoration for flood risk reduction in an urban estuary

- Rae Taylor-Burns

- , Christopher Lowrie

- & Michael W. Beck

Article 20 March 2024 | Open Access

Limited increases in Arctic offshore oil and gas production with climate change and the implications for energy markets

- , Siwa Msangi

- & Stephanie Waldhoff

Changes in landscape and climate in Mexico and Texas reveal small effects on migratory habitat of monarch butterflies ( Danaus plexippus )

- Jay E. Diffendorfer

- , Francisco Botello

- & Victor Sánchez-Cordero

Article 15 March 2024 | Open Access

Exploring urban land surface temperature using spatial modelling techniques: a case study of Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia

- Seyoum Melese Eshetie

Article 13 March 2024 | Open Access

Improving our understanding of future tropical cyclone intensities in the Caribbean using a high-resolution regional climate model

- Job C. M. Dullaart

- , Hylke de Vries

- & Sanne Muis

Article 12 March 2024 | Open Access

A biogeographical appraisal of the threatened South East Africa Montane Archipelago ecoregion

- Julian Bayliss

- , Gabriela B. Bittencourt-Silva

- & Philip J. Platts

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity in meteorological and hydrological drought patterns and propagations influenced by climatic variability, LULC change, and human regulations

- & Xuemei Wang

Article 11 March 2024 | Open Access

Determinants and their spatial heterogeneity of carbon emissions in resource-based cities, China

- Chenchen Guo

- & Jianhui Yu

Climate change, thermal anomalies, and the recent progression of dengue in Brazil

- Christovam Barcellos

- , Vanderlei Matos

- & Rachel Lowe

Editorial 07 March 2024 | Open Access

Advances in green chemistry and engineering

Green chemistry and engineering seek for maximizing efficiency and minimizing negative impacts on the environment and human health in chemical production processes. Driven by advances in the principles of environment protection and sustainability, these fields are expected to greatly contribute to achieving sustainable development goals. To this end, many studies have been conducted to develop new approaches within green chemistry and engineering. The Advances in Green Chemistry and Engineering Collection at Scientific Reports aims at gathering the latest research on developing and implementing the principles of green chemistry and engineering.

- & Assunta Marrocchi

Article 05 March 2024 | Open Access

Comparison of the CASA and InVEST models’ effects for estimating spatiotemporal differences in carbon storage of green spaces in megacities

- Ruei-Yuan Wang

- , Xueying Mo

- & Taohui Li

Article 04 March 2024 | Open Access

Photosynthetic responses of Larix kaempferi and Pinus densiflora seedlings are affected by summer extreme heat rather than by extreme precipitation

- Gwang-Jung Kim

- , Heejae Jo

- & Yowhan Son

Article 03 March 2024 | Open Access

Sounding out maerl sediment thickness: an integrated data approach

- Jack Sheehy

- , Richard Bates

- & Jo Porter

Article 02 March 2024 | Open Access

Rising sea levels and the increase of shoreline wave energy at American Samoa

- Austin T. Barnes

- , Janet M. Becker

- & Mark A. Merrifield

Article 01 March 2024 | Open Access

Amazon savannization and climate change are projected to increase dry season length and temperature extremes over Brazil

- Marcus Jorge Bottino