This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Gates Open Res

‘ It is a question of determination’ : a case study of monitoring and evaluation of integrated family planning services in urban areas of Togo

Helen baker.

1 Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, 30322, USA

Roger Rochat

2 Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, 30322, USA

Kenneth Hepburn

Monique hennink, macoumba thiam.

3 AgirPF, EngenderHealth, Lomé, Togo

Cyrille Guede

Andre koalaga, eloi amegan, koffi fombo, bolatito ogunbiyi.

4 EngenderHealth, Washington D.C., 20004, USA

Lynn Sibley

Associated data, underlying data.

Due to restrictions of access to data outlined in the research participant agreement approved by the Togolese national ethics committee (CBRS), the datasets generated and analyzed during the study are not publicly available. Readers can access data by contacting the Lillian Carter Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University ([email protected]). Data will only be shared with researchers for reanalysis and grant proposals.

Extended data

Figshare: Study Documents Agir03. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7823651.v1 21 .

This project contains the following extended data:

- - Study documents including the protocols, consent forms, health facility assessment forms, and semi-structured interview guides

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Peer Review Summary

Background: Integrating family planning into postabortion and postpartum services can increase contraceptive use and decrease maternal and child death; however, little information exists on the monitoring and evaluation of such programs. This article draws on research completed by the EngenderHealth’s AgirPF project in three urban areas of Togo on the extent to which monitoring and evaluation systems of health services, which operated within the AgirPF project area in Togo, captured integrated family planning services.

Methods: This mixed methods case study used 25 health facility assessments with health service record review in hospitals, large community clinics, a dispensary, and private clinics and 41 key informant interviews with health faculty, individuals working at reproductive health organizations, individuals involved in reproductive health policy and politics, health care workers, and health facility directors.

Results: The study found the reporting system for health care was labor intensive and involved multiple steps for health care workers. The system lacked a standardized method to record family planning services as part of other health care at the patient level, yet the Ministry of Health required integrated family planning services to be reported on district and partner organization reporting forms. Key informants suggested improving the system by using computer-based monitoring, streamlining the reporting process to include all necessary information at the patient level, and standardizing what information is needed for the Ministry of Health and partner organizations.

Conclusion: Future research should focus on assessing the best methods for recording integrated health services and task shifting of reporting. Recommendations for future policy and programming include consolidating data for reproductive health indicators, ensuring type of information needed is captured at all levels, and reducing provider workload for reporting.

Introduction

Interest in providing family planning integrated into other health services has increased in the last five years 1 – 3 . While it is well established that integrating services such as family planning into postabortion and postpartum care can increase contraceptive use and decrease maternal and child deaths 2 , 4 , little information exists on the monitoring and evaluation of such programs at country or regional levels 5 .

Two studies in Togo, the focus of this paper, on postabortion care (PAC) and record keeping at five participating health facility sites documented that in 2014 the monitoring systems for PAC were informal and non-standardized in four of the five facilities 6 . With further training and support, a follow up study in 2016 in the same sites found standardized PAC registers which were generally filled out at the patient level, but the information was not transferred to the district, regional, or national levels 7 .

In opposition to this lack of standardized monitoring, there is increasing interest in monitoring progress towards international benchmarks such as the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as indicators for health initiatives funded by international organizations. Some of the barriers to timely and accurate monitoring include a lack of funding and resource allocation to monitoring and evaluation 8 , a disconnect between expectations of high quality monitoring systems and the level of detail required in reporting 8 – 10 , poor linkages between monitoring systems and points of data generation 11 , a shortage of trained professionals working in monitoring and evaluation 12 – 15 , and the large quantities of required health indicators 8 , which often results in duplication of data collection, and frequent underutilization of existing data collection tools 16 , 17 .

The best methods for reporting integrated family planning programs in practice are still being developed, especially in areas where health care is highly fragmented by type of service delivery (such as vaccination, maternity care, HIV care) 18 – 20 . The published literature lacks information about the processes and strategies for reporting integrated family planning services when implemented 4 .

Project description and study aims

Agir pour la planification familial ( AgirPF ) was a 5-year USAID/West Africa project (2013–2018) implemented by EngenderHealth to build capacity in and increase access to family planning, with interest in the integration of family planning into PAC and postpartum services. AgirPF was implemented in the urban and peri-urban areas of five West African countries- Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Niger, and Togo, in partnership with ministries of health, the private sector, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

In this paper, we describe the extent to which monitoring and evaluation systems of health services, which operated within the AgirPF project area in Togo, captured integrated family planning services. We then examine the influence of values, interests, and power dynamics between key stakeholders on quality of the monitoring and evaluation system and discuss the implications for policy, programming, and research. The paper is based on research that was conducted as part of a larger case study 21 completed by EngenderHealth’s AgirPF project in April-August 2016 with the goal of understanding the status of integrated family planning in urban areas of Togo.

Study design and setting

For this study we used mixed methods including health facility assessments, health service record review, and key-informant interviews. The study was situated in the three largest urban areas in Togo, Lomé (pop. 956,000), Sokodé (pop. 114,800), and Kara (pop. 110,900) 22 . Between February and June 2016, and prior to data collection for this study, AgirPF initiated training around the integration of family planning with other health services. They trained health care workers at 35 facilities in PAC/postabortion care-family planning (PAC-FP), and health care workers at 7 health facilities in postpartum intrauterine device (PPIUD) insertion.

Health facility assessment. We obtained a diverse, purposive sample of 25 health facilities affiliated with AgirPF including university hospitals (n=2), regional hospitals (n=3), district hospitals (n=5), large community health facilities (n=9), a health dispensary (n=1), and private clinics (n=5).

For the assessment, we adapted the Postabortion Care-Family Planning Service Availability and Readiness Assessment 23 and ISSU Enquête Finale au Niveau des Structures de Santé (Final Survey at the Health Facility Level) 2015 24 .The adapted guide contained 194 both open and closed-ended questions. For this part of the health facility assessment, we focused on 19 questions related to monitoring and evaluation of reproductive, sexual, and child health services, and reporting of integrated family planning services.

We trained a data collection team of two nurses and four midwives and pilot tested the guide in July 2016. During the pilot testing and first 3 health facility assessments, the research team discovered that health workers were adapting the government approved and widely used family planning health registers to capture additional aspects of health service integration. This included recording information about what other services the woman received (PAC, postpartum care, immunizations, child health) in addition to whether the woman came on her own or with her husband/male partner. The health facilities also were creating their own unofficial registers to capture information about PAC and general gynecological care.

With this discovery, the health facility assessment team was asked to photograph de-identified filled out health service registers, including family planning, during the health facility assessments. These registers illustrate the different ways in which the registers had been adapted when the official register did not provide a way to capture information needed for reporting to the Ministry of Health and other agencies, including international NGOs.

The team conducted the assessments in person at the selected health facilities. They spoke with a staff member who had been designated by the director of the health facility to participate in the assessment. Since taking photos of the health facilities was not in the original study plan, the data collectors took photographs of different types of available health registers (e.g. not in use or inaccessible), and if the team member had use of a digital camera or smart phone with a camera the day of the health facility assessment. On average the health facility assessments took about three hours to complete by one data collector.

We entered all the closed ended data from the health facility assessment questionnaire into SPSS 24 25 software for cleaning and analysis and compiled the responses from the open-ended questions in tables in MS Word 26 . We used univariate analysis to generate descriptive statistics related to information about reporting on integrated family planning and the services offered at the facility related to integrated family planning. The principal investigator (first author of this article) developed a simple guide to assist with the review and analysis of the photographs by record type.

In-depth interview. We purposively sampled 41 total respondents from diverse professional roles within the Ministry of Health, academic institutions, NGOs/international organizations, and health services. These included faculty at schools of medicine, nursing, and midwifery (n= 3); directors and health workers in health services (n=9 and n=14, respectively); individuals working at reproductive health NGOs/international organizations (n=9); and individuals who worked primarily in reproductive health policy and politics (these included individuals working in the Ministry of Health and NGO workers focused on reproductive health policy) (n=7). This diversity in the sample was intended to elicit a variety of perspectives on reproductive health care from individuals with varying degrees of contact with the AgirPF program activities and trainings related to integrated family planning services. Respondents were recruited by AgirPF through official collaborations with the Togolese Ministry of Health, other reproductive health NGOs, and health facilities.

We developed and pretested five semi-structured interview guides appropriate to the type of respondent. Each of the guides included questions for respondents about multiple different aspects of family planning and integrated family planning in Togo. This paper uses data from the key-informant interviews related to questions about monitoring and evaluation of family planning and integrated family planning.

Five Togolese social scientists and the principal investigator conducted the face-to-face audio-recorded interviews in French. The interviews took place at a time and location chosen by the respondents and took from 30 to 150 minutes to complete. Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim in French by the Togolese social scientists using Express Scribe software version 5.000 27 and then copied into MS Word 2013 26 .

We entered the interview transcripts into Nvivo 11 for analysis 28 and then developed initial codes as well as an initial codebook with the input of Togolese social scientists. The principal investigator then coded all transcripts using the codebook and applied thematic analysis, a rigorous, inductive set of procedures with the goal of identifying and examining themes from textual data in a way which is transparent 29 . Matrices were created in Nvivo to better understand the intricacies of the responses by participant type and location for codes related to monitoring and evaluation of reproductive and sexual health and emerging methods of recording family planning integrated into postabortion and postpartum care. Transcripts were then re-read for further understanding of themes identified, and quotes were chosen to further illustrate selected themes.

Ethical review and informed consent

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University (eIRB#88781), the EngenderHealth Knowledge Management, Monitoring and Evaluation, and Research unit, and the Togolese Ministry of Health Comité de Bioéthique pour la Recherche en Santé (CBRS) (AVIS N o 015/2016/CBRS du 30 juin 2016) . Data were collected only after written informed consent was taken from participants using standard disclosure procedures.

The results are presented beginning with the health facility assessment and health record review followed by the results from the key informant interviews.

Health facility assessment

Description of the facilities. There were 13 facilities in Lomé, four in Sokodé, and eight in Kara, a total of 25 sampled facilities. Eleven of the facilities provided PAC prior to the start of the AgirPF project in 2013. In 2016, 24 of the facilities had some of their health care workers trained by AgirPF in PAC and PAC-FP, 6 had health care workers trained in postpartum family planning (PPFP) and PPIUD insertion. All the health facilities were supported in some way by the AgirPF project. Table 1 shows the types of reproductive and child services available at each health facility with an associated official government issued register or with an unofficial register made by each health facility.

*Italic indicates an “unofficial” register

System of reporting reproductive and child health services

The expected system. The expected flow of information in the system is from the patient to the health facility to the district, regional, national, and international levels of the Ministry of Health ( Figure 1 ). At the patient level, the health care worker must enter and then re-enter information multiple times about a single patient. For information to flow from the patient to facility levels, the health worker must initially enter information into a patient booklet and, for family planning and vaccination, into a patient form for these services. Then the health worker must file the patient form(s) and enter the information in the patient health booklet and sometimes a patient health form into one or more official health register(s). The PPFP/PPIUD register was the only official register which included information about integrated family planning services. This register also had a corresponding book with carbon copy sheets for the monthly reports sent to the Ministry of Health and the partner organizations.

The expected data collection steps and tools used in the reporting process to monitor utilization of integrated family planning services in Togo.

The actual system: individual level reporting. If an official register did not exist for a given service, sometimes NGO workers involved in integration projects would tell health workers to create an unofficial register for the service using a notebook and pen, inserting columns for recording information. Unofficial registers were used most often for general gynecological care (which sometimes included PAC/PAC-FP) as well as PAC/PAC-FP registers. There was little consistency across sites – they were idiosyncratic and site-specific in the unofficial records across the sampled facilities with respect to titles and the information captured. Figure 2 shows the different examples of PAC registers in use and a list of commonly included information in the PAC register.

Common information collected by the Togolese Ministry of Health’s registers and images of the various registers utilized by family planning services reporting system.

Family planning registers were adapted to capture when a client received family planning as part of other health services to enable the health workers to include these data on integrated health services into the monthly service provision reports ( Figure 3 ).

How health workers adapted registers to capture necessary family planning services information necessary to report to the Togolese Ministry of Health and NGOs.

The actual system: facility-level reporting. Within the past two years, the Ministry of Health revised its monthly service provision reporting form, Maternal and Infant Health Report, to include integrated family planning services as outlined in Table 2 . However, the existing service registers were not changed accordingly. As a result, the registers did not always have the data needed to complete the new form at the facility level.

In addition to reporting at facility level for the Ministry of Health, the health care workers were also required to report monthly to the AgirPF project using AgirPF’s form. The respondents also prepared reports for other national and international organizations when asked.

The greatest discrepancy between the sampled facilities with respect to reporting up the chain ( Figure 1 ) was when and where the facility level reports were sent. All 21 of the health facilities which sent reports on integrated family planning sent them monthly. Figure 4 shows the recipients of reports sent by the health facilities. The most common responses included NGOs and the district level Ministry of Health; reports could be sent to more than one recipient.

Where sampled health facilities send monthly monitoring reports and discrepancies between these facilities with respect to reporting up the chain.

Key informant interviews

Table 3 gives information about the 41 key informants involved in the study. Two of the health faculty were trainers for PAC, PAC-FP, PPFP, and PPIUD for the AgirPF project. One health facility director was trained in PAC/PAC-FP and 3 were trained in PPFP/PPIUD. One of the health care workers was a trainer for PAC and 8 had been trained in PAC. Four of the health care workers had been trained in PPFP/PPIUD insertion.

*One key informant was interviewed as both a faculty and health facility assessment.

How family planning registers are being adapted to include integrated family planning data. The health workers interviewed conveyed a great interest in ensuring high quality reporting within the health care registers. What they noted as missing was appropriately formatted registers--both official and unofficial-- which captured all the information required in the facility-level monthly reports sent to the district level of the Ministry of Health and partner NGO projects. This most frequently occurred with the family planning register. One of the educators (02) who also worked as a clinician in a district hospital noted, “ Some indicators that we must track are not noted in some registers, which is worrisome and causes extra work. The registers we have do not conform to the reporting tools. I suggest we review all the registers in use for family planning service providers and make sure they are consistent with the reporting tools. Then reporting would be easy.”

Availability of support for integrated family planning reporting. Individuals involved in reproductive health politics, NGOs, and health facilities directors had varying responses in relation to available support and resources to help implement and record family planning integrated with other health services. All but two respondents to this question felt that further support was necessary and that currently the availability of resources for integrated reporting was lacking, in part because the formats were not as useful as they could be, as described above. A major theme across respondents was how health care workers were already overwhelmed with the amount of required documentation that they were expected to produce. Respondents indicated that future reporting needed to be simplified or it would be necessary to have individuals specifically tasked with reporting. Training of health providers was a prominent request in improved reporting methods.

International NGOs provided health workers with the support for documentation of integrated services. During the PPFP/PPIUD training conducted by Jhpiego and EngenderHealth, health care workers being trained were given hard cover, bound registers approved by the Ministry of Health to record PPFP/PPIUD insertion to use at their respective health facilities as discussed above. One individual involved in reproductive health politics (05) said, “ For PPIUD, Jhpiego provided a register for postpartum care! But postabortion care currently does not even have a proper collection tool. It is handmade and could be used at all levels but is not.”

Uses of family planning data that is reported. There was not consensus as to who used the collected family planning data from the informants. Informants named the Ministry of Health, the Division of Family Health/Division of Maternal and Infant Health/Family Planning, funding organizations, general government, their superior at the health facility, NGOs, United Nations agencies, and/or that it was used at all levels of the health system. Only 6 of 41 informants (three health care workers, three health facility directors) noted that they used the collected data from the health facilities themselves to inform their work and programming.

Challenges and possible solutions associated with reporting integrated family planning services

1. Too many different registers

Adding registers for integrated family planning was the most common way of recording these services. Two informants noted that there were numerous registers for all different types of health care areas and that there may be a point at which the number of registers was becoming excessive. One director (08) noted, “ There are too many registers to fill out, but to get all the integrated services information one is tempted to increase the number of registers. On the other hand, we must rationalize to avoid having too much data to fill in. […] Integrated family planning must also be part of the overall data collection plan that is being worked on at the Ministry of Health. ”

Possible solutions suggested for this problem included bringing in support staff to help the health care workers to complete the reporting or, as noted above, revision and streamlining of relevant health reporting tools. One individual involved in reproductive health policy (01) said, “ It could be helpful if there are specialized services for data collection as well. ”

2. Lack of a standardized reporting system

The need for standardized tools was noted by many of the informants. Without the proper tools to measure the integration of services it is impossible to know if the services are currently being integrated. An individual from a reproductive health NGO (05) said, “ In terms of integration, data collection needs to have integrated tools, […] which must be at all levels of [patient care] delivery.” Possible solutions for this were given by two informants (a health worker and a director) which included having the government officials learn more about reproductive health work needs and implementing electronic systems. One director wanted to make all the reporting in a computerized format, possibly using electronic tablets for providers to enter all data at the patient level.

3. Difficulty in getting access to the registers

More integration of registers took place in smaller health facilities compared to larger hospitals due to the geography of the hospitals and the separation of departments for PAC, labor and delivery, vaccination, and family planning. In the larger hospitals, the different gynecological services were offered in different areas by individuals trained specifically in that area, so the health care staff who oversee the family planning programs were not the ones who were running the PAC services. The hours of service availability also varied depending on the type of service. It was difficult to get the necessary access to these different areas within the larger health facilities to fill out the appropriate register. Often the person doing the PAC service had to go to the family planning service the following day to enter the information about the patient who had received family planning as part of PAC. This person was not necessarily identified specifically as having received family planning as part of PAC unless someone compared the family planning register with the PAC register and identified the woman by name.

In the smaller health facilities, one or two health care providers were responsible for all reproductive health services. This made it easier for them to record the integrated services since they were the ones providing all the services in one location. This way the registers were kept in one area and the health worker had the ability to choose how that register was used and how integrated services were noted.

According to informants, possible solutions to this included having the family planning register available in common locations which all health care workers have access to or change to electronic report (using computers or tablets) on services at the patient level in a platform such as DHIS2. The NGO workers wanted to have further exploration into how the problem of register location could be improved with greater knowledge of the work flow.

4. Too much to record and too little time to do it

Health care workers in Togo provide hundreds of services each month and are required to also chart these services, often in multiple charts and registers by hand. An individual involved in reproductive health politics (01) said, “[Data collection] is done by service providers and they have a lot of work. The providers have to be providers, and I do not know, computer scientist, logistician, as well - they do everything at the same time.” The informants mentioned the large number of tasks health care workers were responsible for throughout the interviews.

Possible solutions posed to this included having less information for the providers to fill out and adapt the reporting tools to streamline the process. One NGO worker (06) said, “We need to have well-designed reporting tools that are not overloaded because […] when there are too many registers to fill in that can cause fatigue. We must […] adapt reporting tools and train personnel in the use of these tools.”

Why family planning reporting matters. The informants agreed that recording family planning played an important role in influencing future service needs. The areas which were prominent included the necessity to be able to make decisions and predict future service use; the ability to monitor improvements or declines in service, and if established goals were met; a way to justify staffing and expenses; and a way to see if there were current unmet needs or new program needs. An informant who worked at a reproductive health NGO (01) noted that while not always used effectively, “ data allows us to know if we are moving towards the goals.”

While there are many challenges to the reporting system, one facility director (07) made a thought-provoking statement when he said, in relation to improving reporting systems in Togo, “ It seems like dreaming, but it is already done elsewhere, and it is a question of determination – we can do this if enough people think it is useful .”

Reducing maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality is a priority of the Togolese government 30 . Integration of family planning into other reproductive health services may help increase the modern contraceptive prevalence rate and decrease the unmet need for contraception which can contribute to reducing maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity. Quality data (e.g. timely, complete, precise and accurate) are key to being able to accurately measure the success of integrated services 31 .

The study findings highlight vulnerabilities with respect to data quality in each link of the reporting chain at the individual patient and facility levels. These findings are unfortunately common. Numerous studies have highlighted the many challenges to reliable and timely information related to health service and health status of the population including problems with completeness, accuracy, and timeliness in low resource settings 32 , 33 , duplicate or parallel reporting systems and lack of capacity for data analysis 34 making planning, monitoring, and evaluation of these programs difficult 35 . In the end, a health monitoring and evaluation system that is designed (unintentionally) to generate poor quality data provides a shaky foundation for health service decision-making, planning, and health policy.

Global discussions around challenges and improvements to reproductive health monitoring and evaluation

Recording information about different types of care in individual registers is not unique to Togo and has been noted in other sub-Saharan African countries 33 , 36 . This type of recording makes it difficult to assign individual identifiers and increases staff workload due to the duplication of material in each register and the frequent changes in data entry protocols 36 . Adapting health care registers to capture the needed information on various reporting forms is also found in other African countries and points to the need to improve and make the health reporting system more flexible to capture multiple service provision in one visit.

In addition, while the innovation shown by the individual health workers in adapting the standard family planning form is important to recognize, it is not a long-term solution to improve the quality, ease, or time requirement of reporting. As in many low-resource countries, some areas of health care provision are supported by donor agencies that fund specific programs which often require additional reporting and documentation. This data should ideally be taken from existing data collection systems but often requires the creation of additional, parallel documents 37 , 38 .

With all the challenges noted above, there is a need to streamline indicators related to maternal health and contraception. One example of this is the FP2020 initiative and the Track20 project, which monitors progress of achieving the FP2020 goals. These goals include increasing modern method users by an additional 120 million women between 2012 and 2020 in the world’s 69 poorest countries, which includes Togo 39 . The Track20 project aims to reduce the need for heavy reliance on large national household surveys and instead use estimates of data collected through the public and private sector on specified family planning indicators 39 . Track20 uses a set of core indicators which were selected through a systematic, consultative process to allow for data-driven decision making by countries and measurement of how well individual needs are met 39 .

Future research questions

Numerous areas require further research into assessing and improving the reporting systems of integrated family planning programs. Time allocation studies of health care providers could show the actual burden on health workers for each type of task and can demonstrate specific areas that may be appropriate for streamlining, including technologies and task shifting that could reduce time burdens. A study of task shifting was undertaken in Botswana involving the creation of a new cadre of health worker, the Monitoring and Evaluation District Officer. These individuals were trained on the job for their tasks 40 . After 3 years on the job, data quality had improved, there was increased use of data for disease surveillance, research, and planning, and nurses and other health professionals had more time to focus on the clinical components of their work 40 . If such task shifting were to be scaled up, health care worker efficiency could improve and burnout could decrease.

Further research is needed to investigate the most effective ways to improve monitoring and evaluation systems themselves, especially in relation to integrated reproductive health programs. A study in Mozambique of a Health Management Mentorship (HMM) program to strengthen health systems in 10 rural districts analyzed change in 4 capacity domains after one year of the program: accounting, human resources, monitoring and evaluation, and transportation management. All the domains except for monitoring and evaluation showed improvement over the one-year mentorship program. The authors of this study noted that challenges included constantly changing program targets and objectives, continually being in a “crisis mode” (constantly trying to catch up on reporting or needing reports in a short period of time) which did not allow time to set up efficient systems, and unavailability of key program staff due to the frequent out-of-office trainings 41 .

This finding shows that monitoring and evaluation systems are difficult to improve even with the deployment of additional resources specifically for this purpose due to the inherent constraints. Implementation research to improve the functionality and sustainability of monitoring and evaluation within the health system, perhaps using a collaborative quality improvement approach, should be considered.

Programming and policy recommendations

Recently, the World Health Organization published results from a five-country intervention to strengthen measurement of reproductive health indicators which aimed to improve national information systems for routine monitoring of reproductive health indicators 42 . Activities within this intervention included revising, standardizing, and making consistent the existing reproductive health indicators gathered through routine systems and building capacity in data collection methods through training and supervision in pilot sites. The country teams reorganized and updated existing monitoring and evaluation frameworks. Challenges encountered even in this focused effort included frequent changes in staffing, delays from administration such as slow response times to updating systems and competing priorities for staff time for implementing reporting improvements. Thus, even with focused intervention it is challenging to streamline and harmonize monitoring and evaluation systems related to reproductive health.

The main recommendations for policy and programming in the Togolese context include consolidating reproductive data for health indicators and reducing provider workload for reporting, especially reporting integrated reproductive health services. This could include adopting electronic data management systems at the health facility level. Currently the largest task of recording integrated family planning is placed on the health care workers, who have adapted health registers to capture the requested information in monthly reports, but this requires extra work, memory, and creativity on the part of the health care worker. When reporting forms are developed they must be standardized to correspond with the associated health register. The number of times the health provider must enter, and re-enter data needs to be reduced.

Limitations

One main limitation of the health facility assessment included that health facilities in the purposive sample were all affiliated with AgirPF and located in urban areas. Another challenge is that the data are cross-sectional and therefore only provide a snapshot of the current monitoring and evaluation system. Lastly, there were challenges associated with photographing registers; however photographs of available registers were only used to illustrate the kinds of adaptations undertaken by health care workers.

Limitations of the key informant interviews included potentially not understanding all the possible perspectives of the informants, differences in the interviewer’s methods for probing and what areas were focused on in each interview, and potential response bias as the study was conducted under the auspices of AgirPF .

Conclusions

Monitoring and evaluation systems are fraught with implementation challenges that affect the quality of data used in patient care, planning, and policy, especially in relation to recording integrated health services. This is a reality not only in Togo but also in other countries. There is a need for a concerted, collaborative effort on the parts of national governments and global partners to address challenges to improve monitoring of integrated health services.

Data availability

Acknowledgements.

We would like to thank the data collectors involved in this research from the URD in Lomé, the Togolese Ministry of Health, and our partner organizations. We also want to recognize the amazing work of Togolese health care providers who work tirelessly to improve access to health care in Togo.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

Funding Statement

This publication was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of the cooperative agreement AID-624-A-13-00004.The contents are the responsibility of authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Reviewer response for version 1

Karen hardee.

1 What Work Association, Arlington, VA, USA

This is an important and well written paper about the complexities of service delivery reporting systems for monitoring integrated family planning services. The paper uses data from the AgirPF project in three urban areas of Togo to trace the expected and actual system for recording family planning integrated with postabortion and postpartum services in 25 health facilities and through 41 key informant interviews. While the focus is integrated services, the findings are applicable to reporting systems for any services and provide a cautionary note for programming that does not pay adequate attention to or funding for M&E. For example, the finding that the relevant registers for PAC are not located in the same place is instructive for understanding the complexities of reporting. The finding that providers are overwhelmed with so much reporting for different purposes is unfortunately not new. The use of visuals to show the workarounds that service providers do in order to record needed indicators is useful for those working on improving reporting of service statistics. I was struck by Figure 4 showing that most monthly reports are sent to NGOs – are those implementing partners funded by donors? Are they contributing to the complexity and work for providers by, as the authors say, “If an official register did not exist for a given services, sometimes NGO workers involved in integration projects would tell health workers to create an unofficial register for the service using a notebook and pen, inserting columns for recording information.”

I did not find the paragraph about FP2020 and Track20 in its current version so relevant to this paper. Service statistics constitute a small component of the data that go into FP2020’s 18 core indicators – and few of the 69 countries have strong enough systems to produce data of sufficient quality to use in the reporting. With that said, I think Track20 is doing interesting work with countries on their routine health systems – particularly to rationalize indicators. Rather than include a summary paragraph about Track20, I suggest that the authors contact Track20 to find out what they are doing related to routine health information systems – so the paragraph can be better tailored to the paper.

I was surprised to see no mention of the work of MEASURE Evaluation, which has for decades been working on improving M&E systems, including routine health information. As one example, through JSI, MEASURE Evaluation has worked on PRISM (Performance of Routine Information System Management), that would be useful to review. Another resource is RHINO, the Routine Health Information Network ( https://www.rhinonet.org/ ). And PEPFAR, with its focus on reporting indicators, has generated lessons learned for strengthening routine health information systems. I suggest that the authors check these resources to strengthen the section of the paper on how to make improvements in the reporting system.

Also, it would be good for the authors to say something about the official process of revising the components of routine health information. For example, who has the authority to make changes to the system? How often are registers reviewed and revised? By who? The authors indicate that some respondents recommended computerized reporting with tablets. Who would have the authority to make this change to the M&E system? Any implementation research carried out to strengthen reporting of integrated family planning services will need to acknowledge the official process for making changes – otherwise, it might just be creating more workarounds.

I confirm that I have read this submission and believe that I have an appropriate level of expertise to confirm that it is of an acceptable scientific standard.

Jane T. Bertrand

1 Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

This article addresses the challenge of monitoring and evaluating integrated family planning services in urban areas of Togo. Specifically, it focuses on the integration of services for family planning, post abortion care, and postpartum care. The findings are based on an assessment of 25 purposively selected health facilities, a review of health services records, and 41 in-depth interviews with different categories of health personnel.

The article is well written and clearly presented. The photos of the registers are useful in reminding readers of the very basic data collection tools available in these facilities. The photos also reflect the attempts by health providers to do the right thing, in the absence of having the appropriate tools to do so.

The paper merits publication because of its systematic examination of the issue of monitoring integrated family planning services. With a new interest in postpartum (and in some countries post-abortion) family planning, this methodological issue is very relevant to those working in family planning. It captures a reality found in many health systems in low-income countries, which often is “understood” but not documented.

The paper effectively communicates the tension between good service provision and timely data collection by low- to middle-level health workers, often poorly paid, who feel overwhelmed by the amount of documentation they are required and expected to produce.

Missing from the paper is a clear statement of what the authors would consider the short list of most valuable indicators to measure integrated family planning. The service providers developed ingenious “work-arounds” to provide information relevant to this question, as they improvised the use of the available forms. If the researchers had full reign over the data collection, what would they recommend? This is particularly relevant, given their citation of the FP 2020 indicators as an example of a standardized set of metrics that countries could then strive to obtain and report. Table 2 provides a list of 13 indicators that includes integrated family planning services. However, the list is long, and the authors don’t attempt to identify or prioritize those of greatest relevance to the question. For readers looking to better understand best practices in the area of measuring integrated family planning services, it’s important to learn what this handful of indicators most important in measuring integrated family planning services would be.

In a related vein, there is lack of a clear path toward a better system. The authors do provide recommendations for improving the quality of service statistics by capturing the data at all levels and reducing the reporting burden on service providers. Yet the very circumstances that created the problems in the current data collection system are fairly ingrained in weak health systems (in Togo and elsewhere). Can the authors provide concrete examples of where their recommendations have actually paid off in other countries?

The following edits would improve the flow and content of the paper:

- Paragraph 3 under the introduction: replace “in opposition to…” with “in contrast to…”

- Under procedures/health facility assessment: The authors clearly explain the purpose of the sample of 25 health facilities. It would be useful to have an approximate estimate of the universe of facilities from which the 25 were selected.

- Under results/health facility assessment: it is not intuitively clear why the researchers took half as many facilities from Sodoké as from Kara, when in the previous section they explain that the population of Sodoké is slightly larger than that of Kara.

- Figure 4. The idea behind this graph and the explanation underneath it do not clearly communicate what it is intended to show. For instance, what the expected/preferred route of transmission?

- On page 10, under “uses of family planning data reported,” the authors make the very salient point that “only six of 41 informants… noted that they use collected data from the health facilities themselves to inform their work and programming.” The author should further develop this issue in the discussion.

With these minor edits, I recommend indexing.

The Monitoring and Evaluation Toolkit

This section asks:

What is a case study?

- What are the different types of case study ?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of a case study ?

- How to Use Case Studies as part of your Monitoring & Evaluation?

There are many different text books and websites explaining the use of case studies and this section draws heavily on those of Lamar University and the NCBI (worked examples), as well as on the author’s own extensive research experience.

If you are monitoring/ evaluating a project, you may already have obtained general information about your target school, village, hospital or farming community. But the information you have is broad and imprecise. It may contain a lot of statistics but may not give you a feel for what is really going on in that village, school, hospital or farming community.

Case studies can provide this depth. They focus on a particular person, patient, village, group within a community or other sub-set of a wider group. They can be used to illustrate wider trends or to show that the case you are examining is broadly similar to other cases or really quite different.

In other words, a case study examines a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity.

A case study paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or among more than two subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or a mixture of the two.

Different types of case study

There are many types of case study. Drawing on the work of Lamar University and the NCBI , some of the best-known types are set out below.

It is best not to worry too much about the nuances that differentiate types of case study. The key is to recognise that the case study is a detailed illustration of how your project or programme has worked or failed to work on an individual, hospital, school, target community or other group/ economic sector.

- Explanatory case studies aim to answer ‘how’ or ’why’ questions with little control on behalf of researcher over occurrence of events. This type of case studies focus on phenomena within the contexts of real-life situations. Example: “An investigation into the reasons of the global financial and economic crisis of 2008 – 2010.”

- Descriptive case studies aim to analyze the sequence of interpersonal events after a certain amount of time has passed. Studies in business research belonging to this category usually describe culture or sub-culture, and they attempt to discover the key phenomena. Example: Impact of increasing levels of funding for prosthetic limbs on the employment opportunities of amputees. A case study of the West Point community of Monrovia (Liberia).

- Exploratory case studies aim to find answers to the questions of ‘what’ or ‘who’. Exploratory case study data collection method is often accompanied by additional data collection method(s) such as interviews, questionnaires, experiments etc. Example: “A study into differences of local community governance practices between a town in francophone Cameroon and a similar-sized town in anglophone Cameroon.”

- Critical instance : This examines a single instance of unique interest, or serves as a critical test of an assertion about a programme, problem or strategy. The focus might be on the economic or human cost of a tsunami or volcanic eruption in a particular area.

- Representative : This relates to case which is typical in nature and representative of other cases that you might examine. An example might be a mother, with a part-time job and four children, living in a community where this is the norm

- Deviant : This refers to a case which is out of line with others. Deviant cases can be particularly interesting and often attract greater attention from analysts. A patient with immunity to a particular virus is worth studying as that study might provide clues to a possible cure to that virus

- Prototypical : This involves a case which is ahead of the curve in some way and has the capacity to set a trend. A particular African town or city may be a free bicyle loan scheme and the experiences of that town might suggest a future path to be followed by other towns and regions.

- Most similar cases : Here you are looking at more than one case and you have selected two cases which have a preponderance of features in common. You might for example be looking at two schools, each of which teaches boys aged from 11-15 and each of which charges similar fees. They are located in the same country but are in different regions where the local authorities devote different levels of resource to secondary school education. You may have a project in each of these areas and you may wish to explain why your project has been more successful in one than the other.

- Most dissimilar cases : these are cases which are, in most key respects, very different and where you might expect to find different outcomes. You might for example select a class of top-ranking pupils and compare it with a class of bottom-ranking puils. This could help to bring out the factors that contribute to or detract from academic success.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Case Study Method

- It helps explain how and why a phenomenon has occurred, thereby going beyond numerical data

- It allows the integration of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods

- It provides rich (or ‘thick) detail and is well suited to capturing complexities of real-life situations and the challenges facing real people

- Case studies (sometimes illustrated with quotations from beneficiairies/ stakeholder and with photographs) are often included as boxes in project reports and evaluations, thereby adding adding a human dimension to an otherwise dry description and data.

- Case studies may offer you an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously.

Disadvantages

- Case studies may be marked by a lack of rigour (e.g. a study may not be sufficiently in-depth or a single case study may not be sufficient)

- Single case studies may offer very little basis for generalisations of findings and conclusions.

- Case studies often tend to be success stories (so they may involve a degree of bias).

Where to next?

Click here to return to the top of the page, here to return to step 3 (Data checking) and here to see a short worked example of a metrics-based evaluation.

- MONITORING AND EVALUATION APPROACHES

- Protected: Learning Center

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) are two essential components of project management that help organizations assess the progress and effectiveness of their programs. Monitoring and evaluation approaches are essential for any organization for measuring the progress and success of any project or program. Evaluation approaches have often been developed to address specific evaluation questions or challenges and they refer to an integrated package of methods and processes.

Table of contents

Results-based monitoring and evaluation approach

Participatory monitoring and evaluation approach, theory-based evaluation approach.

- Utilization-focused evaluation approach

M&E for learning

- Gender-responsive evaluation

Case study evaluation approach

Process monitoring and evaluation approach, impact evaluation approach.

- Evaluation approaches versus evaluation methods

Conclusion on monitoring and evaluation approaches

This approach involves setting specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) indicators for a project and tracking progress against these indicators. It emphasizes the importance of measuring outcomes and impact rather than just activities. Results-based monitoring and evaluation (M&E) approaches can provide the insight needed to evaluate performance and strategy. Results-based M&E involves collecting and analyzing data to assess the impact of programs and identify areas for improvement. It helps organizations understand where they need to focus their resources, and allows them to ensure that projects are meeting established goals. Results-based M&E is an invaluable tool for ensuring efficiency, effectiveness and accountability in any organization’s operations. Read more .

This approach involves involving stakeholders, including beneficiaries, in the monitoring and evaluation process. It can help ensure that the evaluation is sensitive to the needs of those who are intended to benefit from the project. It provides an insight into the progress of the program or project and helps to identify problems that need immediate attention. Participatory monitoring and evaluation approaches help to ensure that all stakeholders are engaged in the evaluation process, bringing a wider perspective and enabling more effective feedback. Through this method, progress and impact can be better understood, allowing for better decisions in order to reach desired outcomes. Participatory approaches are therefore an important part of monitoring and evaluation for any project or program. Read more .

This approach involves examining the underlying theory of change that a project is based on to determine whether the assumptions about how the project will work are valid. It can help identify what changes are likely to occur and how they can be measured. The Theory-based Evaluation approach is a powerful monitoring and evaluation tool that can help organizations make informed decisions about their programs and services. This approach focuses on the underlying theories of change that drive program implementation and outcomes, and helps to identify and address gaps in the program’s effectiveness. It also serves as a way to measure the progress of a program and its impact on the target population. Theory-based evaluation is a comprehensive approach that considers both qualitative and quantitative data, and is useful for understanding the complex relationships between program activities and outcomes. It is an important tool for organizations to ensure that their programs are achieving their intended goals and objectives. Read more.

Utilisation-focused evaluation approach

The Utilisation-focused Evaluation approach is an effective tool for monitoring and evaluation users. It is a user-oriented approach that focuses on the utilisation of evaluation results by intended users and stakeholders. This approach encourages users to be actively involved in the evaluation process, from planning to implementation to reporting. It enables users to assess the impact of the evaluation results on their decision-making and practice. The Utilisation-focused Evaluation approach also encourages users to use the results for further improvement and refinement of their strategies and practices. This approach helps users to identify areas for improvement and to develop strategies to address them. In addition, it helps users to determine the most effective ways to use the evaluation results in order to achieve their desired outcomes. Read more.

Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) for learning is an approach that prioritizes learning and program improvement, as opposed to solely focusing on accountability and reporting to external stakeholders. It is an iterative process that involves continuous monitoring, feedback, and reflection to enable learning and adaptation. By engaging stakeholders in the evaluation process, M&E for learning can identify strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement, and use this information to guide program design and implementation. Ultimately, the goal of M&E for learning is to create a culture of continuous learning within organizations, where learning and adaptation are integrated into every aspect of program design and implementation. Read more .

Gender Responsive Evaluation

A gender-responsive evaluation is an approach to understanding the impacts of a project, policy, or program on women, men and gender diverse populations. It is a valuable tool to assess how different gender groups are affected by a particular project, as well as how to ensure that the project meets its objectives in a way that is equitable and beneficial to all genders. Gender-responsive evaluations also provide useful information on how different gender groups interact and participate in projects or policies, which can help identify any potential inequities in access or outcomes. Read more .

The case study evaluation approach is a powerful tool for monitoring and evaluating the success of a program or initiative. It allows researchers to look at the impact of a program from multiple perspectives, including the behavior of participants and the effectiveness of interventions. By using a case study evaluation approach, researchers can develop a comprehensive picture of the program’s strengths and weaknesses, identify areas for improvement, and make recommendations for future action. This approach is particularly useful for programs that involve multiple stakeholders, as it allows for the examination of both individual and collective outcomes. Furthermore, it is a valuable tool for assessing the program’s effectiveness over time, as it enables researchers to compare the results of different interventions and track changes in program outcomes. Read more.

This approach focuses on how a project is implemented, rather than the outcomes. It can help identify problems in project implementation, such as delays or budget overruns, and make recommendations for improvement. The process monitoring and evaluation approach is a systematic way of tracking and assessing the progress of a project or program. It involves regularly collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data to determine the effectiveness of a program and to identify areas for improvement. Monitoring and evaluation are two distinct but related functions. Monitoring is the continuous collection of information to track the progress of a program or project over time. Evaluation, on the other hand, is the periodic assessment of a program or project to determine its effectiveness and impact. The process monitoring and evaluation approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the program’s strengths and weaknesses, enabling decision-makers to make informed decisions about how to improve the program and ensure its success. Read more.

This approach involves assessing the causal impact of a project on its beneficiaries or the wider community. It can help determine whether a project has achieved its intended outcomes and whether the benefits outweigh the costs. The impact evaluation approach is a monitoring and evaluation technique used to assess the outcomes of a program or intervention. This approach helps to identify the changes that have occurred due to the program or intervention and measure the effectiveness of the program. It is used to evaluate the impact of the program on the target population, such as whether the program has achieved its desired objectives. The impact evaluation approach helps to identify areas of improvement and assess the cost-effectiveness of the program. It also helps to determine whether the program has met its goals and objectives, and if not, what changes should be made in order to achieve the desired results. This approach is a valuable tool for organizations to assess the success of their programs and interventions. Read more.

Evaluation Approaches versus Evaluation Methods

Evaluation approaches and evaluation methods are both used to assess the effectiveness and impact of programs, policies, or interventions. However, they refer to different aspects of the evaluation process.

Evaluation approaches refer to the overall framework or perspective that guides the evaluation. They define the philosophical, theoretical, and methodological principles that underpin the evaluation.

Evaluation methods, on the other hand, are the specific techniques and tools used to collect and analyze data to evaluate the program. Methods can be quantitative (e.g., surveys, experiments, statistical analysis) or qualitative (e.g., interviews, focus groups, content analysis), and may vary depending on the evaluation approach used.

In summary, evaluation approaches define the overall framework and principles that guide the evaluation, while evaluation methods are the specific techniques and tools used to collect and analyze data to evaluate the program.

An effective monitoring and evaluation approach can help to identify whether an organization’s goals are being achieved in a timely manner.

Overall, organizations can use one or more of these approaches to monitoring and evaluation, depending on the needs of their project and the resources available to them. Although there are many different types of monitoring and evaluation approaches available, they all share the same goal – to understand the impact of an organization’s programs and projects on its stakeholders.

This is so detailed and simple to understand. Thanks EvalCommunity for your contribution towards monitoring and evaluation. I always love your resources, thank you!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

How strong is my Resume?

Only 2% of resumes land interviews.

Land a better, higher-paying career

Recommended Jobs

Project assistant, business development/ proposal development consultant, business development associate, senior program associate, ispi, executive assistant (administrative management specialist) – usaid africa, intern- international project and proposal support, ispi, office coordinator, primary health care advisor (locals only), usaid uganda, sudan monitoring project (smp): third party monitoring coordinator, democracy, rights, and governance specialist – usaid ecuador, senior human resources associate.

- United States

Digital MEL Manager – Digital Strategy Implementation Mechanism (DSIM) Washington, DC

- Washington, DC, USA

Senior Accounting Associate

Evaluation consultancy: interculturality for a liberating higher education.

- SAIH (Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ International Assistance Fund)

Program Associate, MERL

Services you might be interested in, useful guides ....

How to Create a Strong Resume

Monitoring And Evaluation Specialist Resume

Resume Length for the International Development Sector

Types of Evaluation

Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL)

LAND A JOB REFERRAL IN 2 WEEKS (NO ONLINE APPS!)

Sign Up & To Get My Free Referral Toolkit Now:

Let your search flow

Explore perspectives, what is a perspective.

Perspectives are different frameworks from which to explore the knowledge around sustainable sanitation and water management. Perspectives are like filters: they compile and structure the information that relate to a given focus theme, region or context. This allows you to quickly navigate to the content of your particular interest while promoting the holistic understanding of sustainable sanitation and water management.

Monitoring and evaluation - TARA (case study)

Executive Summary

This case study supports and illustrates the theoretic factsheet "Monitoring and evaluation (safe water business)" with practical insights.

TARA going from informal, to paper to a mobile app - M&E evolution in India

Informal infrequent M&E

TARAlife produces and sells liquid chlorine to purify drinking water, produced with Antenna Foundation ’s WATA™ technology converting salt and water with a simple electrolysis process into sodium hypochlorite (chlorine). When TARA started producing and selling chlorine branded Aqua+ (see picture) via its social enterprise TARAlife Pvt. Ltd. in 2012, TARA did not have a systematic M&E system in place to monitor sales and business activities. The head of TARAlife simply contacted each local partner by phone on an irregular basis to collect sales figures.

Paper-based

Recognising the importance of collecting customer and sales data in a more systematic way, TARA designed its first M&E system in 2013. This was a sales record booklet which included sections for customer data, sales data, and marketing materials. This system was not functioning properly, because each franchisee filled out the booklet slightly differently and the data were also not reported back to TARA headquarters consistently. This made the data from different regions and last mile agents difficult to compare. At the same time, TARA’s channel partners were having difficulties in managing their Aqua+ stocks, which was causing delayed orders and expired stocks.

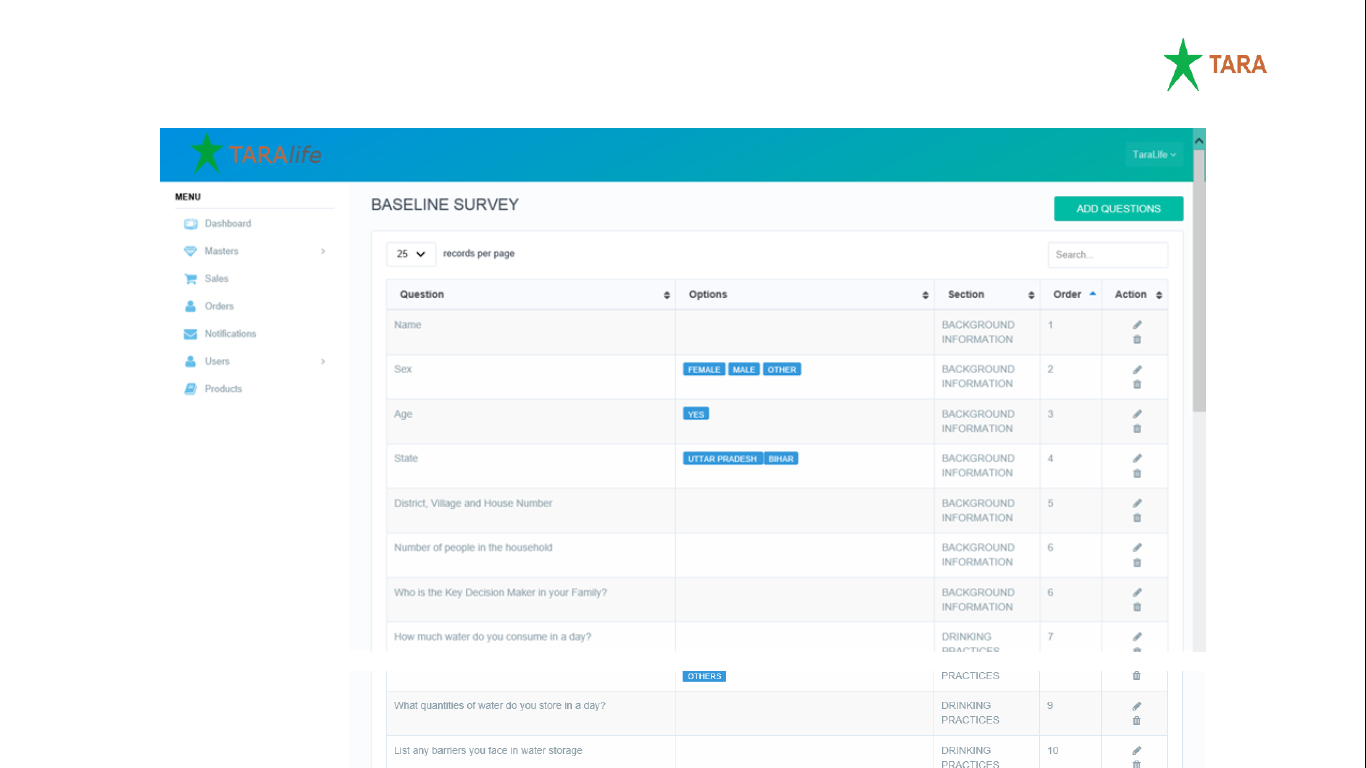

To address both the issues of sales management as well as stock management, TARA started developing a mobile application, with support from a consultant. The app aims to make the sales reporting more user-friendly, more consistent and quicker. When developing the app, TARA realized that it could also be used to collect customer and impact-related data to assess the social, health and financial impacts of TARA's interventions. Together with IRC, the framework for the app (see figure below) was developed based on the following four objectives:

- Retain & increase database of Aqua+ customers

- Track and record impact of intervention on health/overall quality of life

- Decrease or minimise sales lost and inventory costs

- Extend the application of the system to other products than Aqua+ over the long run

The key functions of the application are the following:

- Data collected through the app by micro franchisees: details about customers, micro franchisees, customer purchasing behaviour, baseline survey of potential new customers (i.e. current water disinfection practices, existing health status, medical expenses, etc.), and product feedback from customers.

- Analysis of the data captured with the application: real-time tracking of sales and micro franchisee performance in terms of meeting sales targets.

- Implementation of the data used: send reminders to customers about purchasing TARA products and send periodic messages about safe water awareness.

- Conduct an impact assessment survey (post intervention survey after 6 months of purchase).

The development of the mobile application is completed and it is about to enter the pilot test phase with micro franchisees at TARA Akshar locations in the state of Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. The results from the pilot test are expected by 2018.

Lessons learnt from digitalising M&E

- Paper-based M&E has the advantage that surveys do not need to have access to a source of electricity, which can be advantageous in non-electrified rural areas.

- Paper-based M&E is more time-consuming as to get a clear overview and statistics data has to be fed into computers. During such process mistakes can occur and falsify data.

- The launch of the app-based M&E brings different advantages along: Data is now homogenously compiled and can soundly be tracked back to microfranchisees. It easily allows to make comparisons between regions, products and salespeople on a daily basis.

- App-based M&E allows to be adapted to a variety of products and can be duplicated when necessary.

- App-based M&E improve attractiveness of a safe water initiative or safe water enterprise for investments as impact is soundly collected and can be easily presented and accessed externally also.

Recommendations for implementing an app-based M&E system

- Developing and integrating app-based M&E is time-consuming and has its costs that have to be taken into account when reflecting on starting such project in your safe water initiative.

- In a long-term perspective is the use of app-based M&E inevitable as tendencies are in place of donors and impact investors to have sound track access to data and this if possible on a daily basis.

Safe Water and Jobs - Creating Access to Safe Water in India through Women-Led Service Delivery Models

Taralife sustainability solutions pvt. ltd, alternative versions to, perspective structure.

- Case Studies

You Might Be Interested In

- SDG Background

- Background on "bottom of the pyramid"

- Scaling Safe Water - The Need for an Industry Facilitator

- Operation and Maintenance

You want to stay up to date about water entrepreneurship?

Subscribe here to the new Sanitation and Water Entrepreneurship Pact (SWEP) newsletter!

Contenidos de la ficha

Get regular updates on the latest innovations in SSWM, new perspectives and more!

Do you like our new look?

We'd love to know what you think of the new website – please send us your feedback.

Comparte con otros

Subscribe to our newsletter.

African Monitoring and Evaluation Systems: Exploratory Case Studies

Original bundle.

License bundle

Collections.

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

We use cookies to improve your experience on this website. To learn more, including how to block cookies, read our privacy policy .

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- Collaboration Platform

- Data Portal

- Reporting Tool

- PRI Academy

- PRI Applications

- Back to parent navigation item

- What are the Principles for Responsible Investment?

- PRI 2021-24 strategy

- The PRI work programme

- A blueprint for responsible investment

- About the PRI

- Annual report

- Public communications policy

- Financial information

- Procurement

- PRI sustainability

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion for our employees

- Meet the team

- Board members

- Board committees

- 2023 PRI Board annual elections

- Signatory General Meeting (SGM)

- Signatory rights

- Serious violations policy

- Formal consultations

- Signatories

- Signatory resources

- Become a signatory

- Get involved

- Signatory directory

- Quarterly signatory update

- Multi-lingual resources

- Espacio Hispanohablante

- Programme Francophone

- Reporting & assessment

- R&A Updates

- Public signatory reports

- Progression pathways

- Showcasing leadership

- The PRI Awards

- News & events

- The PRI podcast

- News & press

- Upcoming events

- PRI in Person 2024

- All events & webinars

- Industry events

- Past events

- PRI in Person 2023 highlights

- PRI in Person & Online 2022 highlights

- PRI China Conference: Investing for Net-Zero and SDGs

- PRI Digital Forums

- Webinars on demand

- Investment tools

- Introductory guides to responsible investment

- Principles to Practice

- Stewardship

- Collaborative engagements

- Active Ownership 2.0

- Listed equity

- Passive investments

- Fixed income

- Credit risk and ratings

- Private debt

- Securitised debt

- Sovereign debt

- Sub-sovereign debt

- Private markets

- Private equity

- Real estate

- Climate change for private markets

- Infrastructure and other real assets

- Infrastructure

- Hedge funds

- Investing for nature: Resource hub

- Asset owner resources

- Strategy, policy and strategic asset allocation

- Mandate requirements and RfPs

- Manager selection

- Manager appointment

- Manager monitoring

- Asset owner DDQs

- Sustainability issues

- Environmental, social and governance issues

- Environmental issues

- Circular economy

- Social issues

- Social issues - case studies

- Social issues - podcasts

- Social issues - webinars

- Social issues - blogs

- Cobalt and the extractives industry

- Clothing and Apparel Supply Chain

- Human rights

- Human rights - case studies

- Modern slavery and labour rights

- Just transition

- Governance issues

- Tax fairness

- Responsible political engagement

- Cyber security

- Executive pay

- Corporate purpose

- Anti-corruption

- Whistleblowing

- Director nominations

- Climate change

- The PRI and COP28

- Inevitable Policy Response

- UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance

- Sustainability outcomes

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Sustainable markets

- Sustainable financial system

- Driving meaningful data

- Private retirement systems and sustainability

- Academic blogs

- Academic Seminar series

- Introduction to responsible investing academic research

- Our policy approach

- Policy reports

- Consultations and letters

- Global policy

- Policy toolkit

- Policy engagement handbook

- Regulation database

- A Legal Framework for Impact

- Fiduciary duty

- Australia policy

- Canada Policy

- China policy

- Stewardship in China

- EU taxonomy

- Japan policy

- SEC ESG-Related Disclosure

- More from navigation items

PRI Awards 2019 case study: Portfolio-wide Monitoring and Evaluation Platform

2019-09-10T08:52:00+01:00

Company: Old Mutual Alternative Investments

HQ: South Africa

Category: Real World Impact Initiative of the Year (shortlisted)

In the spirit of showcasing leadership and raising standards of responsible investment among all our signatories, we are pleased to publish case studies of all the winning and shortlisted entries for the PRI Awards 2019.

See the full list

Project overview, objectives, and reasons for undertaking it

African Infrastructure Investment Managers (AIIM) is a wholly owned subsidiary of Old Mutual Alternative Investments. It has shareholdings in 26 renewables assets in South Africa under the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPP). Each is obligated to spend a percentage of profit on socioeconomic development and enterprise development projects within a 50km radius.