- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

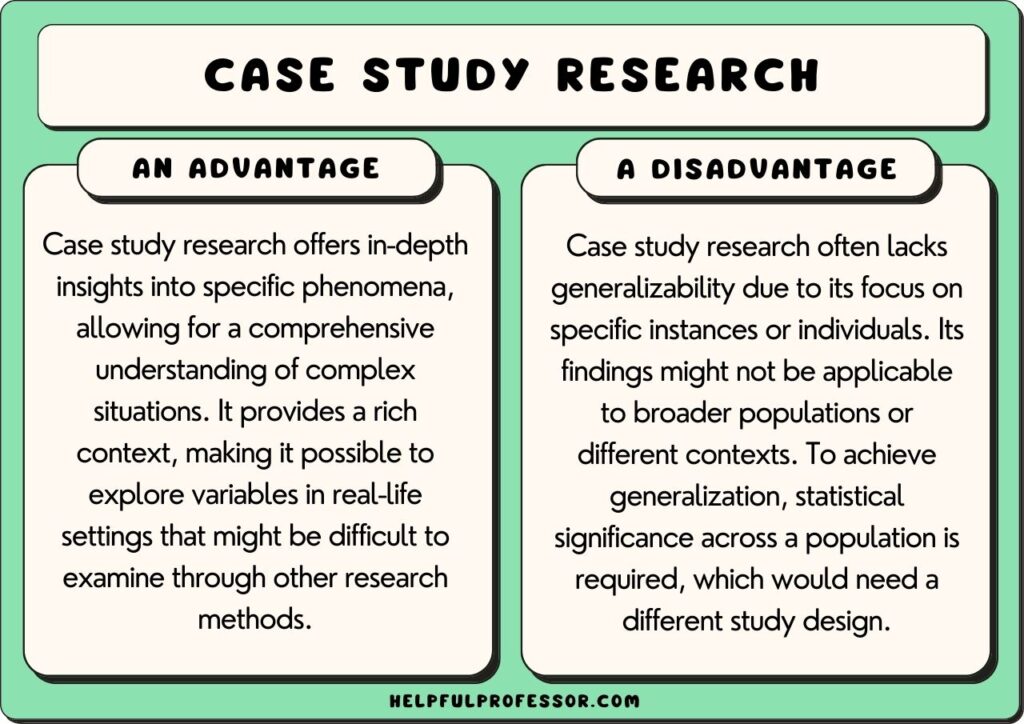

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

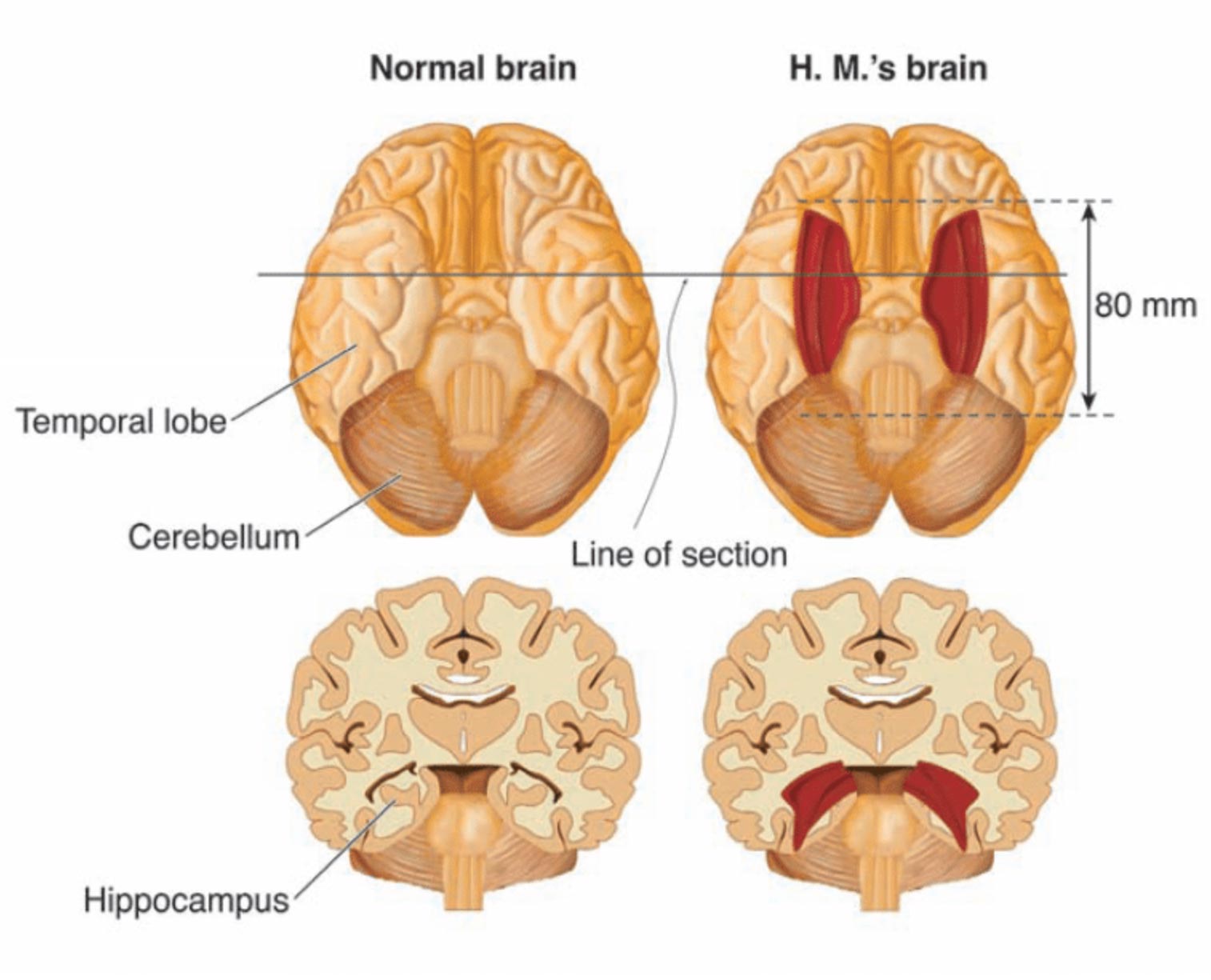

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Final dates! Join the tutor2u subject teams in London for a day of exam technique and revision at the cinema. Learn more →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Study Notes

Case Studies

Last updated 22 Mar 2021

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Case studies are very detailed investigations of an individual or small group of people, usually regarding an unusual phenomenon or biographical event of interest to a research field. Due to a small sample, the case study can conduct an in-depth analysis of the individual/group.

Evaluation of case studies:

- Case studies create opportunities for a rich yield of data, and the depth of analysis can in turn bring high levels of validity (i.e. providing an accurate and exhaustive measure of what the study is hoping to measure).

- Studying abnormal psychology can give insight into how something works when it is functioning correctly, such as brain damage on memory (e.g. the case study of patient KF, whose short-term memory was impaired following a motorcycle accident but left his long-term memory intact, suggesting there might be separate physical stores in the brain for short and long-term memory).

- The detail collected on a single case may lead to interesting findings that conflict with current theories, and stimulate new paths for research.

- There is little control over a number of variables involved in a case study, so it is difficult to confidently establish any causal relationships between variables.

- Case studies are unusual by nature, so will have poor reliability as replicating them exactly will be unlikely.

- Due to the small sample size, it is unlikely that findings from a case study alone can be generalised to a whole population.

- The case study’s researcher may become so involved with the study that they exhibit bias in their interpretation and presentation of the data, making it challenging to distinguish what is truly objective/factual.

- Case Studies

You might also like

A level psychology topic quiz - research methods.

Quizzes & Activities

Case Studies: Example Answer Video for A Level SAM 3, Paper 1, Q4 (5 Marks)

Topic Videos

Research Methods: MCQ Revision Test 1 for AQA A Level Psychology

Example answers for research methods: a level psychology, paper 2, june 2018 (aqa).

Exam Support

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 22 November 2022

Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories

- Lyndsey Nickels ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0311-3524 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Fischer-Baum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6067-0538 3 &

- Wendy Best ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8375-5916 4

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 1 , pages 733–747 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

627 Accesses

5 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neurological disorders

Psychology embraces a diverse range of methodologies. However, most rely on averaging group data to draw conclusions. In this Perspective, we argue that single case methodology is a valuable tool for developing and extending psychological theories. We stress the importance of single case and case series research, drawing on classic and contemporary cases in which cognitive and perceptual deficits provide insights into typical cognitive processes in domains such as memory, delusions, reading and face perception. We unpack the key features of single case methodology, describe its strengths, its value in adjudicating between theories, and outline its benefits for a better understanding of deficits and hence more appropriate interventions. The unique insights that single case studies have provided illustrate the value of in-depth investigation within an individual. Single case methodology has an important place in the psychologist’s toolkit and it should be valued as a primary research tool.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Comparing meta-analyses and preregistered multiple-laboratory replication projects

Amanda Kvarven, Eirik Strømland & Magnus Johannesson

The fundamental importance of method to theory

Rick Dale, Anne S. Warlaumont & Kerri L. Johnson

A critical evaluation of the p-factor literature

Ashley L. Watts, Ashley L. Greene, … Eiko I. Fried

Corkin, S. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life Of The Amnesic Patient, H. M . Vol. XIX, 364 (Basic Books, 2013).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Psychology: From Inquiry To Understanding (Pearson, 2019).

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., Nock, M. K. & Wegner, D. M. Psychology (Worth Publishers, 2019).

Eysenck, M. W. & Brysbaert, M. Fundamentals Of Cognition (Routledge, 2018).

Squire, L. R. Memory and brain systems: 1969–2009. J. Neurosci. 29 , 12711–12716 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Corkin, S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 , 153–160 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schubert, T. M. et al. Lack of awareness despite complex visual processing: evidence from event-related potentials in a case of selective metamorphopsia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 16055–16064 (2020).

Behrmann, M. & Plaut, D. C. Bilateral hemispheric processing of words and faces: evidence from word impairments in prosopagnosia and face impairments in pure alexia. Cereb. Cortex 24 , 1102–1118 (2014).

Plaut, D. C. & Behrmann, M. Complementary neural representations for faces and words: a computational exploration. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 251–275 (2011).

Haxby, J. V. et al. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293 , 2425–2430 (2001).

Hirshorn, E. A. et al. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 8162–8167 (2016).

Kosakowski, H. L. et al. Selective responses to faces, scenes, and bodies in the ventral visual pathway of infants. Curr. Biol. 32 , 265–274.e5 (2022).

Harlow, J. Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Med. Surgical J . https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.11.2.281 (1848).

Broca, P. Remarks on the seat of the faculty of articulated language, following an observation of aphemia (loss of speech). Bull. Soc. Anat. 6 , 330–357 (1861).

Google Scholar

Dejerine, J. Contribution A L’étude Anatomo-pathologique Et Clinique Des Différentes Variétés De Cécité Verbale: I. Cécité Verbale Avec Agraphie Ou Troubles Très Marqués De L’écriture; II. Cécité Verbale Pure Avec Intégrité De L’écriture Spontanée Et Sous Dictée (Société de Biologie, 1892).

Liepmann, H. Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (“motorischen Asymbolie”) auf Grund eines Falles von einseitiger Apraxie (Fortsetzung). Eur. Neurol. 8 , 102–116 (1900).

Article Google Scholar

Basso, A., Spinnler, H., Vallar, G. & Zanobio, M. E. Left hemisphere damage and selective impairment of auditory verbal short-term memory. A case study. Neuropsychologia 20 , 263–274 (1982).

Humphreys, G. W. & Riddoch, M. J. The fractionation of visual agnosia. In Visual Object Processing: A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach 281–306 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987).

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. & Howard, D. A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach To Assessment And Intervention In Aphasia (Psychology Press, 2014).

Caramazza, A. On drawing inferences about the structure of normal cognitive systems from the analysis of patterns of impaired performance: the case for single-patient studies. Brain Cogn. 5 , 41–66 (1986).

Caramazza, A. & McCloskey, M. The case for single-patient studies. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 5 , 517–527 (1988).

Shallice, T. Cognitive neuropsychology and its vicissitudes: the fate of Caramazza’s axioms. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 385–411 (2015).

Shallice, T. From Neuropsychology To Mental Structure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988).

Coltheart, M. Assumptions and methods in cognitive neuropscyhology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 3–22 (Psychology Press, 2001).

McCloskey, M. & Chaisilprungraung, T. The value of cognitive neuropsychology: the case of vision research. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 412–419 (2017).

McCloskey, M. The future of cognitive neuropsychology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 593–610 (Psychology Press, 2001).

Lashley, K. S. In search of the engram. In Physiological Mechanisms in Animal Behavior 454–482 (Academic Press, 1950).

Squire, L. R. & Wixted, J. T. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34 , 259–288 (2011).

Stone, G. O., Vanhoy, M. & Orden, G. C. V. Perception is a two-way street: feedforward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 36 , 337–359 (1997).

Perfetti, C. A. The psycholinguistics of spelling and reading. In Learning To Spell: Research, Theory, And Practice Across Languages 21–38 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997).

Nickels, L. The autocue? self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 9 , 155–182 (1992).

Rapp, B., Benzing, L. & Caramazza, A. The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 14 , 71–104 (1997).

Bonin, P., Roux, S. & Barry, C. Translating nonverbal pictures into verbal word names. Understanding lexical access and retrieval. In Past, Present, And Future Contributions Of Cognitive Writing Research To Cognitive Psychology 315–522 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Gombert, J.-E. Role of phonological and orthographic codes in picture naming and writing: an interference paradigm study. Cah. Psychol. Cogn./Current Psychol. Cogn. 16 , 299–324 (1997).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Peereman, R. Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychol. 99 , 311–328 (1998).

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E. & McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 , 551–565 (1996).

Jeffreys, D. A. Evoked potential studies of face and object processing. Vis. Cogn. 3 , 1–38 (1996).

Laganaro, M., Morand, S., Michel, C. M., Spinelli, L. & Schnider, A. ERP correlates of word production before and after stroke in an aphasic patient. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 374–381 (2011).

Indefrey, P. & Levelt, W. J. M. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition 92 , 101–144 (2004).

Valente, A., Burki, A. & Laganaro, M. ERP correlates of word production predictors in picture naming: a trial by trial multiple regression analysis from stimulus onset to response. Front. Neurosci. 8 , 390 (2014).

Kittredge, A. K., Dell, G. S., Verkuilen, J. & Schwartz, M. F. Where is the effect of frequency in word production? Insights from aphasic picture-naming errors. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 25 , 463–492 (2008).

Domdei, N. et al. Ultra-high contrast retinal display system for single photoreceptor psychophysics. Biomed. Opt. Express 9 , 157 (2018).

Poldrack, R. A. et al. Long-term neural and physiological phenotyping of a single human. Nat. Commun. 6 , 8885 (2015).

Coltheart, M. The assumptions of cognitive neuropsychology: reflections on Caramazza (1984, 1986). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 397–402 (2017).

Badecker, W. & Caramazza, A. A final brief in the case against agrammatism: the role of theory in the selection of data. Cognition 24 , 277–282 (1986).

Fischer-Baum, S. Making sense of deviance: Identifying dissociating cases within the case series approach. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 597–617 (2013).

Nickels, L., Howard, D. & Best, W. On the use of different methodologies in cognitive neuropsychology: drink deep and from several sources. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 475–485 (2011).

Dell, G. S. & Schwartz, M. F. Who’s in and who’s out? Inclusion criteria, model evaluation, and the treatment of exceptions in case series. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 515–520 (2011).

Schwartz, M. F. & Dell, G. S. Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 477–494 (2010).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 , 155–159 (1992).

Martin, R. C. & Allen, C. Case studies in neuropsychology. In APA Handbook Of Research Methods In Psychology Vol. 2 Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, And Biological (eds Cooper, H. et al.) 633–646 (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Leivada, E., Westergaard, M., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Rothman, J. On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition: (how) should we proceed? Bilingualism 24 , 197–210 (2021).

Arnett, J. J. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 63 , 602–614 (2008).

Stolz, J. A., Besner, D. & Carr, T. H. Implications of measures of reliability for theories of priming: activity in semantic memory is inherently noisy and uncoordinated. Vis. Cogn. 12 , 284–336 (2005).

Cipora, K. et al. A minority pulls the sample mean: on the individual prevalence of robust group-level cognitive phenomena — the instance of the SNARC effect. Preprint at psyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bwyr3 (2019).

Andrews, S., Lo, S. & Xia, V. Individual differences in automatic semantic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 43 , 1025–1039 (2017).

Tan, L. C. & Yap, M. J. Are individual differences in masked repetition and semantic priming reliable? Vis. Cogn. 24 , 182–200 (2016).

Olsson-Collentine, A., Wicherts, J. M. & van Assen, M. A. L. M. Heterogeneity in direct replications in psychology and its association with effect size. Psychol. Bull. 146 , 922–940 (2020).

Gratton, C. & Braga, R. M. Editorial overview: deep imaging of the individual brain: past, practice, and promise. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , iii–vi (2021).

Fedorenko, E. The early origins and the growing popularity of the individual-subject analytic approach in human neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , 105–112 (2021).

Xue, A. et al. The detailed organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity within the individual. J. Neurophysiol. 125 , 358–384 (2021).

Petit, S. et al. Toward an individualized neural assessment of receptive language in children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63 , 2361–2385 (2020).

Jung, K.-H. et al. Heterogeneity of cerebral white matter lesions and clinical correlates in older adults. Stroke 52 , 620–630 (2021).

Falcon, M. I., Jirsa, V. & Solodkin, A. A new neuroinformatics approach to personalized medicine in neurology: the virtual brain. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 29 , 429–436 (2016).

Duncan, G. J., Engel, M., Claessens, A. & Dowsett, C. J. Replication and robustness in developmental research. Dev. Psychol. 50 , 2417–2425 (2014).

Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 , aac4716 (2015).

Tackett, J. L., Brandes, C. M., King, K. M. & Markon, K. E. Psychology’s replication crisis and clinical psychological science. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15 , 579–604 (2019).

Munafò, M. R. et al. A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1 , 0021 (2017).

Oldfield, R. C. & Wingfield, A. The time it takes to name an object. Nature 202 , 1031–1032 (1964).

Oldfield, R. C. & Wingfield, A. Response latencies in naming objects. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 17 , 273–281 (1965).

Brysbaert, M. How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. J. Cogn. 2 , 16 (2019).

Brysbaert, M. Power considerations in bilingualism research: time to step up our game. Bilingualism https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000437 (2020).

Machery, E. What is a replication? Phil. Sci. 87 , 545–567 (2020).

Nosek, B. A. & Errington, T. M. What is replication? PLoS Biol. 18 , e3000691 (2020).

Li, X., Huang, L., Yao, P. & Hyönä, J. Universal and specific reading mechanisms across different writing systems. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1 , 133–144 (2022).

Rapp, B. (Ed.) The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (Psychology Press, 2001).

Code, C. et al. Classic Cases In Neuropsychology (Psychology Press, 1996).

Patterson, K., Marshall, J. C. & Coltheart, M. Surface Dyslexia: Neuropsychological And Cognitive Studies Of Phonological Reading (Routledge, 2017).

Marshall, J. C. & Newcombe, F. Patterns of paralexia: a psycholinguistic approach. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2 , 175–199 (1973).

Castles, A. & Coltheart, M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition 47 , 149–180 (1993).

Khentov-Kraus, L. & Friedmann, N. Vowel letter dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 35 , 223–270 (2018).

Winskel, H. Orthographic and phonological parafoveal processing of consonants, vowels, and tones when reading Thai. Appl. Psycholinguist. 32 , 739–759 (2011).

Hepner, C., McCloskey, M. & Rapp, B. Do reading and spelling share orthographic representations? Evidence from developmental dysgraphia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 119–143 (2017).

Hanley, J. R. & Sotiropoulos, A. Developmental surface dysgraphia without surface dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 35 , 333–341 (2018).

Zihl, J. & Heywood, C. A. The contribution of single case studies to the neuroscience of vision: single case studies in vision neuroscience. Psych. J. 5 , 5–17 (2016).

Bouvier, S. E. & Engel, S. A. Behavioral deficits and cortical damage loci in cerebral achromatopsia. Cereb. Cortex 16 , 183–191 (2006).

Zihl, J. & Heywood, C. A. The contribution of LM to the neuroscience of movement vision. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9 , 6 (2015).

Dotan, D. & Friedmann, N. Separate mechanisms for number reading and word reading: evidence from selective impairments. Cortex 114 , 176–192 (2019).

McCloskey, M. & Schubert, T. Shared versus separate processes for letter and digit identification. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 31 , 437–460 (2014).

Fayol, M. & Seron, X. On numerical representations. Insights from experimental, neuropsychological, and developmental research. In Handbook of Mathematical Cognition (ed. Campbell, J.) 3–23 (Psychological Press, 2005).

Bornstein, B. & Kidron, D. P. Prosopagnosia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat. 22 , 124–131 (1959).

Kühn, C. D., Gerlach, C., Andersen, K. B., Poulsen, M. & Starrfelt, R. Face recognition in developmental dyslexia: evidence for dissociation between faces and words. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 38 , 107–115 (2021).

Barton, J. J. S., Albonico, A., Susilo, T., Duchaine, B. & Corrow, S. L. Object recognition in acquired and developmental prosopagnosia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 36 , 54–84 (2019).

Renault, B., Signoret, J.-L., Debruille, B., Breton, F. & Bolgert, F. Brain potentials reveal covert facial recognition in prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 27 , 905–912 (1989).

Bauer, R. M. Autonomic recognition of names and faces in prosopagnosia: a neuropsychological application of the guilty knowledge test. Neuropsychologia 22 , 457–469 (1984).

Haan, E. H. F., de, Young, A. & Newcombe, F. Face recognition without awareness. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 4 , 385–415 (1987).

Ellis, H. D. & Lewis, M. B. Capgras delusion: a window on face recognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5 , 149–156 (2001).

Ellis, H. D., Young, A. W., Quayle, A. H. & De Pauw, K. W. Reduced autonomic responses to faces in Capgras delusion. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 264 , 1085–1092 (1997).

Collins, M. N., Hawthorne, M. E., Gribbin, N. & Jacobson, R. Capgras’ syndrome with organic disorders. Postgrad. Med. J. 66 , 1064–1067 (1990).

Enoch, D., Puri, B. K. & Ball, H. Uncommon Psychiatric Syndromes 5th edn (Routledge, 2020).

Tranel, D., Damasio, H. & Damasio, A. R. Double dissociation between overt and covert face recognition. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 7 , 425–432 (1995).

Brighetti, G., Bonifacci, P., Borlimi, R. & Ottaviani, C. “Far from the heart far from the eye”: evidence from the Capgras delusion. Cogn. Neuropsychiat. 12 , 189–197 (2007).

Coltheart, M., Langdon, R. & McKay, R. Delusional belief. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62 , 271–298 (2011).

Coltheart, M. Cognitive neuropsychiatry and delusional belief. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 60 , 1041–1062 (2007).

Coltheart, M. & Davies, M. How unexpected observations lead to new beliefs: a Peircean pathway. Conscious. Cogn. 87 , 103037 (2021).

Coltheart, M. & Davies, M. Failure of hypothesis evaluation as a factor in delusional belief. Cogn. Neuropsychiat. 26 , 213–230 (2021).

McCloskey, M. et al. A developmental deficit in localizing objects from vision. Psychol. Sci. 6 , 112–117 (1995).

McCloskey, M., Valtonen, J. & Cohen Sherman, J. Representing orientation: a coordinate-system hypothesis and evidence from developmental deficits. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 23 , 680–713 (2006).

McCloskey, M. Spatial representations and multiple-visual-systems hypotheses: evidence from a developmental deficit in visual location and orientation processing. Cortex 40 , 677–694 (2004).

Gregory, E. & McCloskey, M. Mirror-image confusions: implications for representation and processing of object orientation. Cognition 116 , 110–129 (2010).

Gregory, E., Landau, B. & McCloskey, M. Representation of object orientation in children: evidence from mirror-image confusions. Vis. Cogn. 19 , 1035–1062 (2011).

Laine, M. & Martin, N. Cognitive neuropsychology has been, is, and will be significant to aphasiology. Aphasiology 26 , 1362–1376 (2012).

Howard, D. & Patterson, K. The Pyramids And Palm Trees Test: A Test Of Semantic Access From Words And Pictures (Thames Valley Test Co., 1992).

Kay, J., Lesser, R. & Coltheart, M. PALPA: Psycholinguistic Assessments Of Language Processing In Aphasia. 2: Picture & Word Semantics, Sentence Comprehension (Erlbaum, 2001).

Franklin, S. Dissociations in auditory word comprehension; evidence from nine fluent aphasic patients. Aphasiology 3 , 189–207 (1989).

Howard, D., Swinburn, K. & Porter, G. Putting the CAT out: what the comprehensive aphasia test has to offer. Aphasiology 24 , 56–74 (2010).

Conti-Ramsden, G., Crutchley, A. & Botting, N. The extent to which psychometric tests differentiate subgroups of children with SLI. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 40 , 765–777 (1997).

Bishop, D. V. M. & McArthur, G. M. Individual differences in auditory processing in specific language impairment: a follow-up study using event-related potentials and behavioural thresholds. Cortex 41 , 327–341 (2005).

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A. & Greenhalgh, T., and the CATALISE-2 consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: terminology. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 58 , 1068–1080 (2017).

Wilson, A. J. et al. Principles underlying the design of ‘the number race’, an adaptive computer game for remediation of dyscalculia. Behav. Brain Funct. 2 , 19 (2006).

Basso, A. & Marangolo, P. Cognitive neuropsychological rehabilitation: the emperor’s new clothes? Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 10 , 219–229 (2000).

Murad, M. H., Asi, N., Alsawas, M. & Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. Evidence-based Med. 21 , 125–127 (2016).

Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J. & Maskrey, N., for the Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? Br. Med. J. 348 , g3725–g3725 (2014).

Best, W., Ping Sze, W., Edmundson, A. & Nickels, L. What counts as evidence? Swimming against the tide: valuing both clinically informed experimentally controlled case series and randomized controlled trials in intervention research. Evidence-based Commun. Assess. Interv. 13 , 107–135 (2019).

Best, W. et al. Understanding differing outcomes from semantic and phonological interventions with children with word-finding difficulties: a group and case series study. Cortex 134 , 145–161 (2021).

OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. CEBM https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (2011).

Holler, D. E., Behrmann, M. & Snow, J. C. Real-world size coding of solid objects, but not 2-D or 3-D images, in visual agnosia patients with bilateral ventral lesions. Cortex 119 , 555–568 (2019).

Duchaine, B. C., Yovel, G., Butterworth, E. J. & Nakayama, K. Prosopagnosia as an impairment to face-specific mechanisms: elimination of the alternative hypotheses in a developmental case. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 23 , 714–747 (2006).

Hartley, T. et al. The hippocampus is required for short-term topographical memory in humans. Hippocampus 17 , 34–48 (2007).

Pishnamazi, M. et al. Attentional bias towards and away from fearful faces is modulated by developmental amygdala damage. Cortex 81 , 24–34 (2016).

Rapp, B., Fischer-Baum, S. & Miozzo, M. Modality and morphology: what we write may not be what we say. Psychol. Sci. 26 , 892–902 (2015).

Yong, K. X. X., Warren, J. D., Warrington, E. K. & Crutch, S. J. Intact reading in patients with profound early visual dysfunction. Cortex 49 , 2294–2306 (2013).

Rockland, K. S. & Van Hoesen, G. W. Direct temporal–occipital feedback connections to striate cortex (V1) in the macaque monkey. Cereb. Cortex 4 , 300–313 (1994).

Haynes, J.-D., Driver, J. & Rees, G. Visibility reflects dynamic changes of effective connectivity between V1 and fusiform cortex. Neuron 46 , 811–821 (2005).

Tanaka, K. Mechanisms of visual object recognition: monkey and human studies. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7 , 523–529 (1997).

Fischer-Baum, S., McCloskey, M. & Rapp, B. Representation of letter position in spelling: evidence from acquired dysgraphia. Cognition 115 , 466–490 (2010).

Houghton, G. The problem of serial order: a neural network model of sequence learning and recall. In Current Research In Natural Language Generation (eds Dale, R., Mellish, C. & Zock, M.) 287–319 (Academic Press, 1990).

Fieder, N., Nickels, L., Biedermann, B. & Best, W. From “some butter” to “a butter”: an investigation of mass and count representation and processing. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 31 , 313–349 (2014).

Fieder, N., Nickels, L., Biedermann, B. & Best, W. How ‘some garlic’ becomes ‘a garlic’ or ‘some onion’: mass and count processing in aphasia. Neuropsychologia 75 , 626–645 (2015).

Schröder, A., Burchert, F. & Stadie, N. Training-induced improvement of noncanonical sentence production does not generalize to comprehension: evidence for modality-specific processes. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 195–220 (2015).

Stadie, N. et al. Unambiguous generalization effects after treatment of non-canonical sentence production in German agrammatism. Brain Lang. 104 , 211–229 (2008).

Schapiro, A. C., Gregory, E., Landau, B., McCloskey, M. & Turk-Browne, N. B. The necessity of the medial temporal lobe for statistical learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26 , 1736–1747 (2014).

Schapiro, A. C., Kustner, L. V. & Turk-Browne, N. B. Shaping of object representations in the human medial temporal lobe based on temporal regularities. Curr. Biol. 22 , 1622–1627 (2012).

Baddeley, A., Vargha-Khadem, F. & Mishkin, M. Preserved recognition in a case of developmental amnesia: implications for the acaquisition of semantic memory? J. Cogn. Neurosci. 13 , 357–369 (2001).

Snyder, J. J. & Chatterjee, A. Spatial-temporal anisometries following right parietal damage. Neuropsychologia 42 , 1703–1708 (2004).

Ashkenazi, S., Henik, A., Ifergane, G. & Shelef, I. Basic numerical processing in left intraparietal sulcus (IPS) acalculia. Cortex 44 , 439–448 (2008).

Lebrun, M.-A., Moreau, P., McNally-Gagnon, A., Mignault Goulet, G. & Peretz, I. Congenital amusia in childhood: a case study. Cortex 48 , 683–688 (2012).

Vannuscorps, G., Andres, M. & Pillon, A. When does action comprehension need motor involvement? Evidence from upper limb aplasia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 253–283 (2013).

Jeannerod, M. Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. NeuroImage 14 , S103–S109 (2001).

Blakemore, S.-J. & Decety, J. From the perception of action to the understanding of intention. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 , 561–567 (2001).

Rizzolatti, G. & Craighero, L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27 , 169–192 (2004).

Forde, E. M. E., Humphreys, G. W. & Remoundou, M. Disordered knowledge of action order in action disorganisation syndrome. Neurocase 10 , 19–28 (2004).

Mazzi, C. & Savazzi, S. The glamor of old-style single-case studies in the neuroimaging era: insights from a patient with hemianopia. Front. Psychol. 10 , 965 (2019).

Coltheart, M. What has functional neuroimaging told us about the mind (so far)? (Position Paper Presented to the European Cognitive Neuropsychology Workshop, Bressanone, 2005). Cortex 42 , 323–331 (2006).

Page, M. P. A. What can’t functional neuroimaging tell the cognitive psychologist? Cortex 42 , 428–443 (2006).

Blank, I. A., Kiran, S. & Fedorenko, E. Can neuroimaging help aphasia researchers? Addressing generalizability, variability, and interpretability. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 377–393 (2017).

Niv, Y. The primacy of behavioral research for understanding the brain. Behav. Neurosci. 135 , 601–609 (2021).

Crawford, J. R. & Howell, D. C. Comparing an individual’s test score against norms derived from small samples. Clin. Neuropsychol. 12 , 482–486 (1998).

Crawford, J. R., Garthwaite, P. H. & Ryan, K. Comparing a single case to a control sample: testing for neuropsychological deficits and dissociations in the presence of covariates. Cortex 47 , 1166–1178 (2011).

McIntosh, R. D. & Rittmo, J. Ö. Power calculations in single-case neuropsychology: a practical primer. Cortex 135 , 146–158 (2021).

Patterson, K. & Plaut, D. C. “Shallow draughts intoxicate the brain”: lessons from cognitive science for cognitive neuropsychology. Top. Cogn. Sci. 1 , 39–58 (2009).

Lambon Ralph, M. A., Patterson, K. & Plaut, D. C. Finite case series or infinite single-case studies? Comments on “Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology” by Schwartz and Dell (2010). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 466–474 (2011).

Horien, C., Shen, X., Scheinost, D. & Constable, R. T. The individual functional connectome is unique and stable over months to years. NeuroImage 189 , 676–687 (2019).

Epelbaum, S. et al. Pure alexia as a disconnection syndrome: new diffusion imaging evidence for an old concept. Cortex 44 , 962–974 (2008).

Fischer-Baum, S. & Campana, G. Neuroplasticity and the logic of cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 403–411 (2017).

Paul, S., Baca, E. & Fischer-Baum, S. Cerebellar contributions to orthographic working memory: a single case cognitive neuropsychological investigation. Neuropsychologia 171 , 108242 (2022).

Feinstein, J. S., Adolphs, R., Damasio, A. & Tranel, D. The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear. Curr. Biol. 21 , 34–38 (2011).

Crawford, J., Garthwaite, P. & Gray, C. Wanted: fully operational definitions of dissociations in single-case studies. Cortex 39 , 357–370 (2003).

McIntosh, R. D. Simple dissociations for a higher-powered neuropsychology. Cortex 103 , 256–265 (2018).

McIntosh, R. D. & Brooks, J. L. Current tests and trends in single-case neuropsychology. Cortex 47 , 1151–1159 (2011).

Best, W., Schröder, A. & Herbert, R. An investigation of a relative impairment in naming non-living items: theoretical and methodological implications. J. Neurolinguistics 19 , 96–123 (2006).

Franklin, S., Howard, D. & Patterson, K. Abstract word anomia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 12 , 549–566 (1995).

Coltheart, M., Patterson, K. E. & Marshall, J. C. Deep Dyslexia (Routledge, 1980).

Nickels, L., Kohnen, S. & Biedermann, B. An untapped resource: treatment as a tool for revealing the nature of cognitive processes. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 539–562 (2010).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of those pioneers of and advocates for single case study research who have mentored, inspired and encouraged us over the years, and the many other colleagues with whom we have discussed these issues.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychological Sciences & Macquarie University Centre for Reading, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Lyndsey Nickels

NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Aphasia Recovery and Rehabilitation, Australia

Psychological Sciences, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA

Simon Fischer-Baum

Psychology and Language Sciences, University College London, London, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.N. led and was primarily responsible for the structuring and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lyndsey Nickels .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Yanchao Bi, Rob McIntosh, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nickels, L., Fischer-Baum, S. & Best, W. Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories. Nat Rev Psychol 1 , 733–747 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00127-y

Download citation

Accepted : 13 October 2022

Published : 22 November 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00127-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- First Online: 27 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- R. M. Channaveer 4 &

- Rajendra Baikady 5

2193 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter reviews the strengths and limitations of case study as a research method in social sciences. It provides an account of an evidence base to justify why a case study is best suitable for some research questions and why not for some other research questions. Case study designing around the research context, defining the structure and modality, conducting the study, collecting the data through triangulation mode, analysing the data, and interpreting the data and theory building at the end give a holistic view of it. In addition, the chapter also focuses on the types of case study and when and where to use case study as a research method in social science research.

- Qualitative research approach

- Social work research

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Ang, C. S., Lee, K. F., & Dipolog-Ubanan, G. F. (2019). Determinants of first-year student identity and satisfaction in higher education: A quantitative case study. SAGE Open, 9 (2), 215824401984668. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019846689

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2015). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report . Published. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

Bhatta, T. P. (2018). Case study research, philosophical position and theory building: A methodological discussion. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 12 , 72–79. https://doi.org/10.3126/dsaj.v12i0.22182

Article Google Scholar

Bromley, P. D. (1990). Academic contributions to psychological counselling. A philosophy of science for the study of individual cases. Counselling Psychology Quarterly , 3 (3), 299–307.

Google Scholar

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11 (1), 1–9.

Grässel, E., & Schirmer, B. (2006). The use of volunteers to support family carers of dementia patients: Results of a prospective longitudinal study investigating expectations towards and experience with training and professional support. Zeitschrift Fur Gerontologie Und Geriatrie, 39 (3), 217–226.

Greenwood, D., & Lowenthal, D. (2005). Case study as a means of researching social work and improving practitioner education. Journal of Social Work Practice, 19 (2), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650530500144782

Gülseçen, S., & Kubat, A. (2006). Teaching ICT to teacher candidates using PBL: A qualitative and quantitative evaluation. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 9 (2), 96–106.

Gomm, R., Hammersley, M., & Foster, P. (2000). Case study and generalization. Case study method , 98–115.

Hamera, J., Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). Performance ethnography . SAGE.

Hayes, N. (2000). Doing psychological research (p. 133). Open University Press.

Harrison, H., Birks, M., Franklin, R., & Mills, J. (2017). Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. In Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: Qualitative social research (Vol. 18, No. 1).

Iwakabe, S., & Gazzola, N. (2009). From single-case studies to practice-based knowledge: Aggregating and synthesizing case studies. Psychotherapy Research, 19 (4–5), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802688494

Johnson, M. P. (2006). Decision models for the location of community corrections centers. Environment and Planning b: Planning and Design, 33 (3), 393–412. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3125

Kaarbo, J., & Beasley, R. K. (1999). A practical guide to the comparative case study method in political psychology. Political Psychology, 20 (2), 369–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895x.00149

Lovell, G. I. (2006). Justice excused: The deployment of law in everyday political encounters. Law Society Review, 40 (2), 283–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2006.00265.x

McDonough, S., & McDonough, S. (1997). Research methods as part of English language teacher education. English Language Teacher Education and Development, 3 (1), 84–96.

Meredith, J. (1998). Building operations management theory through case and field research. Journal of Operations Management, 16 (4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6963(98)00023-0

Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of case study research . Sage Publications.

Ochieng, P. A. (2009). An analysis of the strengths and limitation of qualitative and quantitative research paradigms. Problems of Education in the 21st Century , 13 , 13.

Page, E. B., Webb, E. J., Campell, D. T., Schwart, R. D., & Sechrest, L. (1966). Unobtrusive measures: Nonreactive research in the social sciences. American Educational Research Journal, 3 (4), 317. https://doi.org/10.2307/1162043

Rashid, Y., Rashid, A., Warraich, M. A., Sabir, S. S., & Waseem, A. (2019). Case study method: A step-by-step guide for business researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18 , 160940691986242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919862424

Ridder, H. G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research, 10 (2), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-017-0045-z

Sadeghi Moghadam, M. R., Ghasemnia Arabi, N., & Khoshsima, G. (2021). A Review of case study method in operations management research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20 , 160940692110100. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211010088

Sommer, B. B., & Sommer, R. (1997). A practical guide to behavioral research: Tools and techniques . Oxford University Press.

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work .

Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research . Sage Publications.

Stoecker, R. (1991). Evaluating and rethinking the case study. The Sociological Review, 39 (1), 88–112.

Suryani, A. (2013). Comparing case study and ethnography as qualitative research approaches .

Taylor, S., & Berridge, V. (2006). Medicinal plants and malaria: An historical case study of research at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the twentieth century. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 100 (8), 707–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.11.017

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report . Published. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/1997.2024

Towne, L., & Shavelson, R. J. (2002). Scientific research in education . National Academy Press Publications Sales Office.

Widdowson, M. D. J. (2011). Case study research methodology. International Journal of Transactional Analysis Research, 2 (1), 25–34.

Yin, R. K. (2004). The case study anthology . Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Design and methods. Case Study Research , 3 (9.2).

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.). Sage Publishing.

Yin, R. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods . Sage Publications Beverly Hills.

Yin, R. (1993). Applications of case study research . Sage Publishing.

Zainal, Z. (2003). An investigation into the effects of discipline-specific knowledge, proficiency and genre on reading comprehension and strategies of Malaysia ESP Students. Unpublished Ph. D. Thesis. University of Reading , 1 (1).

Zeisel, J. (1984). Inquiry by design: Tools for environment-behaviour research (No. 5). CUP archive.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Work, Central University of Karnataka, Kadaganchi, India

R. M. Channaveer

Department of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rajendra Baikady

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to R. M. Channaveer .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Family and Child Studies, Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

M. Rezaul Islam

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Department of Social Work, School of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Channaveer, R.M., Baikady, R. (2022). Case Study. In: Islam, M.R., Khan, N.A., Baikady, R. (eds) Principles of Social Research Methodology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_21

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_21

Published : 27 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-5219-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-5441-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Case Studies

March 7, 2021 - Paper 2 Psychology in Context | Research Methods

- Back to Paper 2 - Research Methods

Description, AO1 of Case Studies:

- An in-depth, detailed investigation of an individual or group.

- It would usually include biographical details, as well as details of behaviours or experiences of interest to the researcher.

- Usually carried out in the real world

- Can use a variety of Psychology research methods (experimental and non-experimental) in order to collect data for the case study.

Methods used to collect information for case studies:

- Questionnaires (open and closed questions)

- Observations

Evaluation of Case Studies:

(1) POINT: A strength of a case study is that it produces rich, detailed data. EXAMPLE: For example, a case study of an individual’s life is incredibly detailed and may highlight a number of important experiences that could have combined to cause them to become mentally ill. EVALUATION: This is positive because information that may be overlooked using other methods is likely to be identified.

(2) POINT: A strength os a cause study is that it provices insight into individuals. EXAMPLE: For example, rare mental disorders make it impossible to study large amounts of participants with that disorder because the behaviours or experiences are so unique that they could not have been studied in any other way. EVALUATION: This is positive because it helps to improve our understanding of behaviours that would otherwise not be possible.

Weaknesses:

(1) POINT: A weakness of a case study is that it is difficult to generalise the results. EXAMPLE: For example, a case study of an individual person might not be representative of anyone else because experiences are so individual that another person may not react in the same way. EVALUATION: This is a problem as it’s difficult to generalise to the rest of the population (low popultation validity) as each case has unique characteristics.

(2) POINT: A weakness of a case study is that it collects retrospective data. EXAMPLE: For example, a researcher might rely on asking individuals about their past to help form the case study, which can be reconstructive. EVALUATION: This is a problem as such evidence may have been recalled inaccurately and may therefore be unreliable.

- Psychopathology

- Social Psychology

- Approaches To Human Behaviour

- Biopsychology

- Research Methods

- Issues & Debates

- Teacher Hub

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- [email protected]

- www.psychologyhub.co.uk

We're not around right now. But you can send us an email and we'll get back to you, asap.

Start typing and press Enter to search

Cookie Policy - Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

2.2 Approaches to Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the different research methods used by psychologists

- Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of case studies, naturalistic observation, surveys, and archival research

- Compare longitudinal and cross-sectional approaches to research

- Compare and contrast correlation and causation

There are many research methods available to psychologists in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior and the cognitive and biological processes that underlie it. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions to extensive, in-depth interviews—to well-controlled experiments.

Each of these research methods has unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control on how or what kind of data was collected. All of the methods described thus far are correlational in nature. This means that researchers can speak to important relationships that might exist between two or more variables of interest. However, correlational data cannot be used to make claims about cause-and-effect relationships.

Correlational research can find a relationship between two variables, but the only way a researcher can claim that the relationship between the variables is cause and effect is to perform an experiment. In experimental research, which will be discussed later in this chapter, there is a tremendous amount of control over variables of interest. While this is a powerful approach, experiments are often conducted in artificial settings. This calls into question the validity of experimental findings with regard to how they would apply in real-world settings. In addition, many of the questions that psychologists would like to answer cannot be pursued through experimental research because of ethical concerns.

Clinical or Case Studies

In 2011, the New York Times published a feature story on Krista and Tatiana Hogan, Canadian twin girls. These particular twins are unique because Krista and Tatiana are conjoined twins, connected at the head. There is evidence that the two girls are connected in a part of the brain called the thalamus, which is a major sensory relay center. Most incoming sensory information is sent through the thalamus before reaching higher regions of the cerebral cortex for processing.

Link to Learning

Watch this CBC video about Krista's and Tatiana's lives to learn more.

The implications of this potential connection mean that it might be possible for one twin to experience the sensations of the other twin. For instance, if Krista is watching a particularly funny television program, Tatiana might smile or laugh even if she is not watching the program. This particular possibility has piqued the interest of many neuroscientists who seek to understand how the brain uses sensory information.

These twins represent an enormous resource in the study of the brain, and since their condition is very rare, it is likely that as long as their family agrees, scientists will follow these girls very closely throughout their lives to gain as much information as possible (Dominus, 2011).

Over time, it has become clear that while Krista and Tatiana share some sensory experiences and motor control, they remain two distinct individuals, which provides invaluable insight for researchers interested in the mind and the brain (Egnor, 2017).

In observational research, scientists are conducting a clinical or case study when they focus on one person or just a few individuals. Indeed, some scientists spend their entire careers studying just 10–20 individuals. Why would they do this? Obviously, when they focus their attention on a very small number of people, they can gain a precious amount of insight into those cases. The richness of information that is collected in clinical or case studies is unmatched by any other single research method. This allows the researcher to have a very deep understanding of the individuals and the particular phenomenon being studied.

If clinical or case studies provide so much information, why are they not more frequent among researchers? As it turns out, the major benefit of this particular approach is also a weakness. As mentioned earlier, this approach is often used when studying individuals who are interesting to researchers because they have a rare characteristic. Therefore, the individuals who serve as the focus of case studies are not like most other people. If scientists ultimately want to explain all behavior, focusing attention on such a special group of people can make it difficult to generalize any observations to the larger population as a whole. Generalizing refers to the ability to apply the findings of a particular research project to larger segments of society. Again, case studies provide enormous amounts of information, but since the cases are so specific, the potential to apply what’s learned to the average person may be very limited.

Naturalistic Observation

If you want to understand how behavior occurs, one of the best ways to gain information is to simply observe the behavior in its natural context. However, people might change their behavior in unexpected ways if they know they are being observed. How do researchers obtain accurate information when people tend to hide their natural behavior? As an example, imagine that your professor asks everyone in your class to raise their hand if they always wash their hands after using the restroom. Chances are that almost everyone in the classroom will raise their hand, but do you think hand washing after every trip to the restroom is really that universal?

This is very similar to the phenomenon mentioned earlier in this chapter: many individuals do not feel comfortable answering a question honestly. But if we are committed to finding out the facts about hand washing, we have other options available to us.

Suppose we send a classmate into the restroom to actually watch whether everyone washes their hands after using the restroom. Will our observer blend into the restroom environment by wearing a white lab coat, sitting with a clipboard, and staring at the sinks? We want our researcher to be inconspicuous—perhaps standing at one of the sinks pretending to put in contact lenses while secretly recording the relevant information. This type of observational study is called naturalistic observation : observing behavior in its natural setting. To better understand peer exclusion, Suzanne Fanger collaborated with colleagues at the University of Texas to observe the behavior of preschool children on a playground. How did the observers remain inconspicuous over the duration of the study? They equipped a few of the children with wireless microphones (which the children quickly forgot about) and observed while taking notes from a distance. Also, the children in that particular preschool (a “laboratory preschool”) were accustomed to having observers on the playground (Fanger, Frankel, & Hazen, 2012).

It is critical that the observer be as unobtrusive and as inconspicuous as possible: when people know they are being watched, they are less likely to behave naturally. If you have any doubt about this, ask yourself how your driving behavior might differ in two situations: In the first situation, you are driving down a deserted highway during the middle of the day; in the second situation, you are being followed by a police car down the same deserted highway ( Figure 2.7 ).

It should be pointed out that naturalistic observation is not limited to research involving humans. Indeed, some of the best-known examples of naturalistic observation involve researchers going into the field to observe various kinds of animals in their own environments. As with human studies, the researchers maintain their distance and avoid interfering with the animal subjects so as not to influence their natural behaviors. Scientists have used this technique to study social hierarchies and interactions among animals ranging from ground squirrels to gorillas. The information provided by these studies is invaluable in understanding how those animals organize socially and communicate with one another. The anthropologist Jane Goodall , for example, spent nearly five decades observing the behavior of chimpanzees in Africa ( Figure 2.8 ). As an illustration of the types of concerns that a researcher might encounter in naturalistic observation, some scientists criticized Goodall for giving the chimps names instead of referring to them by numbers—using names was thought to undermine the emotional detachment required for the objectivity of the study (McKie, 2010).

The greatest benefit of naturalistic observation is the validity , or accuracy, of information collected unobtrusively in a natural setting. Having individuals behave as they normally would in a given situation means that we have a higher degree of ecological validity, or realism, than we might achieve with other research approaches. Therefore, our ability to generalize the findings of the research to real-world situations is enhanced. If done correctly, we need not worry about people or animals modifying their behavior simply because they are being observed. Sometimes, people may assume that reality programs give us a glimpse into authentic human behavior. However, the principle of inconspicuous observation is violated as reality stars are followed by camera crews and are interviewed on camera for personal confessionals. Given that environment, we must doubt how natural and realistic their behaviors are.

The major downside of naturalistic observation is that they are often difficult to set up and control. In our restroom study, what if you stood in the restroom all day prepared to record people’s hand washing behavior and no one came in? Or, what if you have been closely observing a troop of gorillas for weeks only to find that they migrated to a new place while you were sleeping in your tent? The benefit of realistic data comes at a cost. As a researcher you have no control of when (or if) you have behavior to observe. In addition, this type of observational research often requires significant investments of time, money, and a good dose of luck.

Sometimes studies involve structured observation. In these cases, people are observed while engaging in set, specific tasks. An excellent example of structured observation comes from Strange Situation by Mary Ainsworth (you will read more about this in the chapter on lifespan development). The Strange Situation is a procedure used to evaluate attachment styles that exist between an infant and caregiver. In this scenario, caregivers bring their infants into a room filled with toys. The Strange Situation involves a number of phases, including a stranger coming into the room, the caregiver leaving the room, and the caregiver’s return to the room. The infant’s behavior is closely monitored at each phase, but it is the behavior of the infant upon being reunited with the caregiver that is most telling in terms of characterizing the infant’s attachment style with the caregiver.

Another potential problem in observational research is observer bias . Generally, people who act as observers are closely involved in the research project and may unconsciously skew their observations to fit their research goals or expectations. To protect against this type of bias, researchers should have clear criteria established for the types of behaviors recorded and how those behaviors should be classified. In addition, researchers often compare observations of the same event by multiple observers, in order to test inter-rater reliability : a measure of reliability that assesses the consistency of observations by different observers.

Often, psychologists develop surveys as a means of gathering data. Surveys are lists of questions to be answered by research participants, and can be delivered as paper-and-pencil questionnaires, administered electronically, or conducted verbally ( Figure 2.9 ). Generally, the survey itself can be completed in a short time, and the ease of administering a survey makes it easy to collect data from a large number of people.

Surveys allow researchers to gather data from larger samples than may be afforded by other research methods . A sample is a subset of individuals selected from a population , which is the overall group of individuals that the researchers are interested in. Researchers study the sample and seek to generalize their findings to the population. Generally, researchers will begin this process by calculating various measures of central tendency from the data they have collected. These measures provide an overall summary of what a typical response looks like. There are three measures of central tendency: mode, median, and mean. The mode is the most frequently occurring response, the median lies at the middle of a given data set, and the mean is the arithmetic average of all data points. Means tend to be most useful in conducting additional analyses like those described below; however, means are very sensitive to the effects of outliers, and so one must be aware of those effects when making assessments of what measures of central tendency tell us about a data set in question.

There is both strength and weakness of the survey in comparison to case studies. By using surveys, we can collect information from a larger sample of people. A larger sample is better able to reflect the actual diversity of the population, thus allowing better generalizability. Therefore, if our sample is sufficiently large and diverse, we can assume that the data we collect from the survey can be generalized to the larger population with more certainty than the information collected through a case study. However, given the greater number of people involved, we are not able to collect the same depth of information on each person that would be collected in a case study.

Another potential weakness of surveys is something we touched on earlier in this chapter: People don't always give accurate responses. They may lie, misremember, or answer questions in a way that they think makes them look good. For example, people may report drinking less alcohol than is actually the case.