- Technical Help

- CE/CME Help

- Billing Help

- Sales Inquiries

- CE Certificates

- Billing Inquiries

- Purchase Inquiries

Good Clinical Practice (GCP)

GCP consists of basic and refresher courses that provide essential good clinical practice training for research teams involved in clinical trials. Improve site activation time and reduce training time with mutually-recognized, effective, engaging training.

About these Courses

Good Clinical Practice (GCP) includes basic courses tailored to the different types of clinical research. Basic courses provide in-depth foundational training. We also offer completely fresh content in Refresher courses for retraining and advanced learners. Our courses include effective and innovative eLearning techniques such as in-module knowledge checks, case studies, and audio-visual delivery.

CITI Program GCP training is used by over 1,500 institutions - (including many leading hospitals, academic medical centers, universities, and healthcare companies) - to meet their GCP training needs. The National Institutes of Health (NIH)* requires completion of GCP training that demonstrates that individuals have attained the fundamental knowledge of clinical trial quality standards for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve human research participants.

GCP courses cover applicable U.S. FDA regulations, ICH E6(R2) GCP principles and practices, and the ISO 14155:2020 standard.

The following GCP ICH E6 Investigator Site Training courses also meet the Minimum Criteria for ICH GCP Investigator Site Personnel Training identified by TransCelerate BioPharma as necessary to enable mutual recognition of GCP training among trial sponsors and have been updated to include ICH E6(R2):

Basic Courses - English with ICH E6(R2)

- GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Medical Devices (U.S. FDA Focus)

- GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Biologics (ICH Focus)

Refresher Courses - English with ICH E6(R2)

GCP FDA Refresher

Gcp ich refresher, gcp sbr advanced refresher.

These courses were written and peer-reviewed by experts.

* NIH in fulfillment of their GCP training policy (Policy on Good Clinical Practice Training for NIH Awardees Involved in NIH-funded Clinical Trials; NOT-OD-16-148) states that NIH-funded investigators and staff should be trained in GCP. The NIH does not endorse any specific training programs. CITI Program offers several GCP courses that are considered acceptable by many leading organizations to meet their training needs per NIH policy released on 16 September 2016. Course completion certificates and reports are provided to learners at the completion of a course and are sharable via unique hyperlink or PDF making training documentation seamless for sponsors and sites.

Language Availability: Chinese, English, Korean, Spanish, Finnish, French, German

Suggested Audiences: Clinical Research Coordinators (CRCs), Contract Research Organizations (CROs), Investigators, IRB Members, Key Study Personnel, Principal Investigators, Research Nurses, Research Staff, Researchers, Sponsors, Study Coordinators

Basic Courses

Gcp for clinical investigations of drugs and devices (fda).

Ideal for individuals proposing to conduct clinical trials of drugs, biologics, and devices primarily in the U.S.

GCP for Clinical Investigations of Drugs and Biologics (ICH)

Ideal for individuals proposing to conduct clinical trials of drugs and biologics in the U.S. or internationally.

GCP for Clinical Investigations of Devices

This course provides training for research personnel involved in clinical investigations of devices.

GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research

This course is suitable for social and behavioral investigators and staff who must be trained in GCP.

Refresher Courses

This refresher course provides retraining on GCP for clinical trials with investigational drugs and medical devices (U.S. FDA f...

This refresher course offers retraining on GCP for clinical trials with investigational drugs and biologics (ICH focus).

GCP Device Refresher

This refresher course provides retraining on GCP for clinical investigations of devices.

Provides retraining on GCP principles suitable for social and behavioral investigators and staff.

Is GCP training the same as human subjects protection training?

No. GCP training is a separate training and is not basic human subjects protection training. GCP principles are specific to clinical trials and include international ethical and scientific quality standards for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting clinical trials.

Does CITI Program offer GCP training that is compliant with the NIH policy?

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) in fulfillment of their GCP training policy (Policy on Good Clinical Practice Training for NIH Awardees Involved in NIH-funded Clinical Trials; NOT-OD-16-148) states that NIH-funded investigators and staff should be trained in GCP.

The NIH requires completion of GCP training that demonstrates that individuals have attained the fundamental knowledge of clinical trial quality standards for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve human research participants.

The NIH does not endorse any specific training programs.

CITI Program offers several GCP courses that are considered acceptable by many leading organizations to meet their training needs per NIH.

See the course descriptions above for more information on individual courses. These articles identify courses that comply with the NIH GCP Policy and answer FAQs for NIH Policy on GCP training .

Who should take GCP training?

GCP content is suitable for research teams involved in clinical trials of drugs, biologics, and devices, as well as those involved in behavioral intervention and social science research studies.

How do I know which GCP course I should take?

Learners should take the GCP course that best meets the type of research they conduct:

- GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Medical Devices (U.S. FDA Focus) and GCP FDA Refresher are suitable for individuals proposing to conduct clinical trials of drugs and devices primarily in the U.S. and/or who would prefer a more U.S. FDA-centric curriculum.

- GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Biologics (ICH Focus) and GCP ICH Refresher are suitable for individuals involved in clinical trials of drugs and biologics when the research may be international or where the individuals would prefer a more ICH-focused curriculum.

- GCP for Clinical Investigations of Devices and GCP Device Refresher are most appropriate for organizations or individuals who desire a more international-focused GCP curriculum and a more device-focused program. These device courses cover FDA regulation as well as International Organization for Standardization Guidelines ISO 14155:2011.

- GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research and GCP SBR Advanced Refresher are suitable for social and behavioral investigators and staff who must be trained in GCP.

How long does it take to complete a GCP course?

GCP courses vary on the number of modules they contain. Modules consist of detailed content, images, supplemental materials (such as case studies), and a quiz. Learners may complete the modules at their own pace. As a rule of thumb, modules can take about 30 to 45 minutes to complete, which means it could take around three to six hours to complete a GCP course.

How frequently should learners take GCP training?

There is no uniform standard regarding how frequently GCP training should occur. However, most organizations select a three-year period of retraining. The organization could request that the designated refresher course or the same basic course be presented to learners again within a given period.

Are GCP courses mutually recognized by TransCelerate BioPharma as meeting the minimum GCP ICH criteria?

Yes, five of CITI Program's GCP courses are mutually recognized. See the individual course pages for more information on TransCelerate mutual recognition, including requirements (such as module requirements) for organizations and learners to utilize the mutually recognized courses. The Support article List of TransCelerate Mutually Recognized GCP Training includes each mutually recognized course and the required modules.

Please also note that organizations and learners that wish to utilize these mutually recognized GCP courses in keeping with the minimum criteria must designate all available modules as “Required.”

How do I know if my GCP course will be mutually recognized by TransCelerate BioPharma and study monitors?

Learners who fulfill a GCP course’s requirements (complete all the required modules after the effective date) will see a statement in the Description field on their Completion Report’s “Transcript Report” (part 2 of a Completion Report) or on their Certificate. The statement identifies the GCP course’s name and information regarding mutual recognition.

- Version 1 refers to the ICH E6(R1) minimum criteria that was used to attest the course for mutual recognition to TransCelerate BioPharma.

- Version 2 refers to the ICH E6(R2) revisions to the TransCelerate BioPharma’s minimum criteria for mutual recognition. CITI Program has updated all TransCelerate attested GCP courses to meet the version 2 minimum criteria. If you complete your GCP course after the effective date for version 2, your Completion Report will indicate that on the Transcript Report (it will include the course name and which version you completed).

If you completed your GCP course before version 2 was available (or before the effective date for version 2), you can return to the course and re-take the modules. After you complete all the required modules, your Completion Report and Certificate will indicate that you completed version 2.

The following Support articles provide additional information:

- CITI Program Guide to GCP Mutual Recognition

- Guide to GCP Mutual Recognition Completion Documentation

- List of TransCelerate Mutually Recognized GCP Training

- Reading and Understanding a CITI Program Completion Report and Certificate for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) TransCelerate BioPharma Mutually Recognized Training

Do I need to submit or self-attest my CITI Program GCP course to TransCelerate BioPharma to receive mutual recognition?

No, you should not submit or self-attest a course to TransCelerate BioPharma. CITI Program submits and self-attests on behalf of our GCP courses.

We ensure that our mutually recognized GCP courses satisfy the requirements for mutual recognition and that completion documentation reflect the course name, version number, and all required elements (including TransCelerate information) if a learner completes a mutually recognized course.

Do the CITI Program GCP courses reflect the changes from ICH E6(R2)?

Yes, after the ICH Integrated Addendum to ICH E6(R1): Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2 ) was adopted on 15 December 2016, the CITI Program modules were revised to reflect the current guideline. The GCP courses that reference ICH E6 specifically refer to the current guideline.

CITI Program also offers some additional resources on ICH E6(R2).

- An additional module of interest titled “Overview of ICH GCP E6(R2) Revisions” can be added to GCP courses. This module reviews the additions that led to the publication of the ICH E6(R2) guideline and discusses the new approaches for the management of clinical trials – including quality management, risk-based monitoring, and data integrity.

- A free resource that provides an overview of the ICH E6(R2) integrated addendum is available on CITI Program’s Resources page . This resource covers the revisions to the International Council for Harmonistion (ICH) “Integrated Addendum to ICH E6(R1): Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2),” including a breakdown by section with summaries and analysis. The revised ICH E6(R2) guideline includes changes that affect sponsors, researchers, and IRBs.

Do the CITI Program GCP courses reflect the ISO 14155:2020 updated standard for GCP?

Yes, the CITI Program modules were updated in December 2020 and reflect ISO 14155:2020.

Additionally, the GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Medical Devices (U.S. FDA Focus) course and the GCP Device Refresher course both include specific content on ISO 14155.

What is the value of a refresher course and what is its role in training?

A refresher course provides retraining. Using CITI Program refresher course options to provide retraining means that the learner will not be completing the same course every time.

When should I take a GCP refresher course?

GCP refresher courses are meant to reinforce the importance of concepts covered in the basic level GCP course. The CITI Program recommends that learners complete the basic level GCP course first, and then take a refresher GCP course at the interval designated by their organization.

As an administrator setting up my organization, how should I select GCP courses for my learner groups?

CITI Program allows organizations to customize their learner groups, which means they can choose the modules their learners need to complete. We will work with your CITI Program designated admin to determine the learner groups that best fit your organizational needs.

For basic GCP courses, it is highly recommended that organizations present all modules in a given course as required for a learner to earn a completion report. Some organizations will make several modules supplemental, particularly when they provide organization-specific training on the topic.

Is this GCP course eligible for continuing medical education credits?

Yes, the following courses are eligible for CME credits:

- GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Medical Devices (U.S. FDA Focus) Course

- GCP for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Biologics (ICH Focus) Course

- GCP FDA Refresher Course

- GCP ICH Refresher Course

- GCP for Clinical Investigations of Devices Course

- GCP – Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research

Click on the course name above for details. For more information on how to ensure CME credit availability for learners at your organization, contact [email protected] or 888.529.5929.

What are the advantages of CITI Program's GCP training?

GCP provides research-specific, peer-reviewed training written by GCP experts. Along with CITI Program's advantages, including our experience, customization options, cost effectiveness, and focus on organizational and learner needs, this makes it an excellent choice for GCP training.

Do social and behavioral researchers need to take GCP?

All NIH-funded investigators and staff who are involved in the conduct, oversight, or management of research that meets the definition of a clinical trial should be trained in GCP. A clinical trial is defined by NIH as a research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.

Will I be notified if this course is significantly revised or updated?

Yes, CITI Program will notify administrators via email and post news articles on our website when courses are significantly revised or updated.

Who developed the GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research course?

The development of the GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research course was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program, grant number 3UL1TR000433.

Can I change the passing score for the GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research course?

The creators of this course have set the passing score at 100 percent and organizations are not able to change or customize the passing score for this course.

How does the GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research course differ from other GCP courses?

The GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research course applies GCP principles to behavioral intervention and social science research studies. Other GCP courses cover drug, device, and biologic-related studies.

Can I combine the GCP - Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices for Clinical Research course with other courses?

It is recommend that the course not be combined with other courses.

Privacy Overview

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network

Good clinical practice, updated gcp course.

NDAT CTN Training is pleased to announce that the GCP training website has been up-versioned to include design and e-learning modifications as well as incorporating the recent modifications made to the GCP guidelines. The new interactive course is now available at: https://gcp.nidatraining.org .

To learn more about the new website and see the enhanced features, please click here: https://gcp.nidatraining.com/promo.

The Good Clinical Practice (GCP) course is designed to prepare research staff in the conduct of clinical trials with human participants. The 12 modules included in the course are based on ICH GCP Principles and the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) for clinical research trials in the U.S. The course is self-paced and takes approximately six hours to complete.

To preview the new enhanced features, please click here .

To begin, please sign in using the link to the right if you have already created an account. If you do not have an account, click here to register.

Need an account? Sign up here!

Course Topics

- Introduction

- Institutional Review Boards

- Informed Consent

- Confidentiality & Privacy

- Participant Safety & Adverse Events

- Quality Assurance

- The Research Protocol

- Documentation & Record-Keeping

- Research Misconduct

- Roles & Responsibilities

- Recruitment & Retention

- Investigational New Drugs

Certification

Users are required to complete a quiz following each module, except for the Introduction module. To receive a certificate, all quizzes must be completed with at least 80% accuracy (a 100% passing option is available if required by your IRB). Upon successful completion of all quizzes, the user will be given access to the Certificate of Completion. Within the NIDA Clinical Trials Network, certification expires after three years.

GxP Lifeline

Good clinical practices and 5 common gcp violations in clinical studies.

Clinical trials are conducted to allow safety and efficacy data to be collected for health interventions, including drugs, biologics, devices, and therapy protocols. These trials can only take place once satisfactory information has been gathered on the quality of the non-clinical safety. Good Clinical Practices (GCPs) provide a platform for the quality of the data and a unified standard for the conduct of clinical trials.

What GCPs Require of a Clinical Study

GCPs describe information to be included in the Investigator's Brochure (IB), a comprehensive document summarizing the body of information about an investigational product (IP) or study drug. The purpose of the IB is to compile data relevant to studies of the IP in human subjects gathered during preclinical and other clinical trials. GCPs define the essential documents necessary to permit evaluation of a clinical study and the quality of data generated.

The investigational product or study drug must be handled and prepared in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) and used in accordance with the protocol instructions. Informed consent must be obtained from all subjects prior to participation in the clinical study.

In a clinical study, all data must be recorded, handled, and stored properly. Confidentiality of subject records must be maintained in accordance with applicable regulatory requirements. Patient rights, safety, and well-being are of primary concern. Foreseeable risks and inconveniences should be weighed against anticipated benefit. Clinical trials should be scientifically sound and clearly described in the study protocol. The clinical trial should be conducted in compliance with the study protocol.

The clinical study must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB), a committee that has been formally designated to approve, monitor, and review biomedical and behavioral research involving humans with the aim to protect the rights and welfare of the subjects. Most importantly, a qualified physician must conduct the clinical study.

Overview of the Regulatory Requirements

These requirements describe the conditions under which clinical data from investigational studies would be acceptable in support of a regulatory submission for the approval and commercial use of a drug, biologic, or medical device. The data from the clinical trial is included in regulatory submissions .

These requirements form the basis of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inspection activities for clinical trials. When the FDA inspects a clinical trial, they are looking at the following regulations and subparts, including the sections contained therein:

- 21 CFR Part 50 – Protection of Human Subjects

- Informed Consent.

- 21 CFR Part 56 – IRBs

- General Provisions.

- Organization and Personnel.

- IRB Functions and Operations.

- Records and Reports.

- Administrative Actions for Noncompliance.

- 21 CFR Part 312 – Investigational New Drug Application (IND)

- Responsibilities of Sponsors and Investigators.

The data for the clinical trial can be electronic or paper-based. Whichever is used, it must be accurate, complete, legible, and recorded in a timely manner. Maintain trial documents during and after conclusion of the study for at least 10 years, as a review of the data will be done by the study sponsor, but it also may be done by the IRB, the FDA, or another regulatory agency.

The FDA conducts routine and for-cause inspections of IRBs, and the Division of Scientific Investigations, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), maintains an inventory of IRBs that have been inspected. Sponsors can find out if an IRB has been inspected by the FDA, along with the results of the inspection, through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) procedures.

Another area the FDA has been focusing on in recent years is ensuring compounded product quality, with traditional compounding facilities coming under greater scrutiny. Through enforcement actions, the agency has been addressing manufacturing quality issues at compounders’ facilities, particularly GMP compliance in outsourcing facilities.

5 Most Common GCP Violations in Clinical Studies

The following are the most common issues cited in FDA inspections of clinical trials, based on my experience as an auditor of clinical trials for study sponsors:

Protocol adherence

Adherence to the study protocol is critical; too many waivers or deviations from the study protocol are unacceptable. If exceptions, protocol violations, and/or deviations are allowed by the study sponsor, they must be documented properly (with the appropriate signatures). Entering ineligible subjects in a study is a common citation; all subjects must meet the eligibility as defined in the protocol.

Clinical records

Records must confirm the diagnosis or the inclusion and exclusion criteria. There must be evidence of physician oversight (the principal investigator and the sub-investigator). The information within a subject's chart or medical history must be in agreement with the study records. Records must be secure at all times and cannot be lost, misplaced, or destroyed.

Informed consent

The informed consent must have the study subjects’ signatures and the date, and it must be signed and dated prior to any study procedures being performed. The most current, IRB-approved informed consent must be the consent signed. The consenting process must have adequate documentation describing the consent process. Most importantly, the informed consent must be written in a language understood by the study subject.

Drug accountability

Drug accountability is an important component of a study. Records cannot be completed retroactively. Drug storage conditions must be monitored and access to the study drug must be limited to study personnel as documented on the study responsibility log.

Adverse events

The reporting of serious adverse events (SAEs) is very important to the FDA because study subjects’ safety is their primary focus. Therefore, it is critical to report all SAEs in a timely manner. They must be documented in subject source records, not only in the case report forms. Any and all laboratory abnormalities must be reviewed and addressed (clinically significant or not clinically significant) by the principal investigator.

What is important to remember is that the protection of the rights of subjects and the safety of the subjects is paramount. This can be obtained by thorough oversight by the sponsor, meticulous documentation, and excellent monitoring by the study monitor.

Michelle Sceppa is the Principal at MSceppa Consulting , an established consulting firm in its 18th year in industry. MSceppa Consulting specializes in quality systems for Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology interests and has implemented and managed preclinical, clinical, and manufacturing quality assurance programs for numerous clients. As the lead auditor, MSceppa Consulting has conducted and managed more than 500 internal and external vendor audits for drug and biologic firms in the U.S. and Europe. MSceppa Consulting is knowledgeable in the details of compliance with all U.S. federal regulations – Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) for drugs, biologics, and medical devices.

Free Resource

Enjoying this blog? Learn More.

21 CFR Part 11 Industry Overview: Ready for an FDA Inspection?

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 02 July 2020

All research needs to follow the rules set down by Good Clinical Practice

- Inge-Marie Velstra 1 &

- Angela Frotzler 1

Spinal Cord volume 58 , pages 947–948 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2058 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Health services

All researchers are obliged to follow the very detailed principles/rules of the International Conference on Harmonization—Good Clinical Practice (GCP). GCP is an international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting studies that involve the participation of human participants [ 1 ]. GCP is particularly important for clinical trials.

In investigator-initiated trials, the investigator (or institution) has to assume the sponsor responsibility. Main aspects of sponsor responsibilities are implementing a quality management system on an organizational and study level, risk management, data management, teaching/training, and risk-based monitoring [ 1 ]. Thus, the sponsor has to address many different GCP requirements. However, since GCP tells us just “what to do” but not “how to do it”, the implementation of GCP often leads to frustration mainly due to its complexity, strictness and comprehensiveness. In our experience, study teams often consider the GCP guidelines as very burdensome to implement. However, fulfilling the GCP requirements is only our duty while doing clinical research but also a valuable guide to ensure participants’ rights, well-being and safety, as well as data quality.

In the past, traditional monitoring was mostly based on frequent on-site visits and source data verification (e.g. checking Case Report Form data against source documentation, i.e. in patient charts). There is evidence that 100% source data verification during monitoring is less useful than originally thought, recognizing that not all clinical studies require the same monitoring approach and extent to ensure data quality or patient safety. Therefore in 2016, the concept of risk-based monitoring was introduced in the addendum to the International Conference on Harmonization—GCP E6 (R2) guideline. This requires the sponsor to develop a systematic, prioritized, risk-based approach to monitoring clinical trials [ 1 ]. In risk-based monitoring, the risk of GCP deviations is assessed for a certain study center and type of clinical study. If the risk is high, frequent on-site monitoring visits are required, and if the risk is low, minimal on-site visits are scheduled. Hence, in risk-based monitoring the extent and nature of monitoring is flexible, and the goal is to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of monitoring. However, it is not always clear how to set up risk-based monitoring for clinical research projects. The establishment of an appropriate monitoring plan is still a challenge, although monitoring is simplified with the concept of risk-based monitoring. Thus, we recommend involving an experienced person in risk-based monitoring, for support with the writing of a monitoring plan according to the institutional conditions (like financial resources or existence of a quality management system).

There are various risk-based monitoring tools available [ 2 , 3 ]. In our institution, risk-based monitoring is generally based on the concept of Risk ADApted MONitoring [ 4 ] and is applied in both interventional and observational studies. Our common findings (i.e., GCP deviations) during monitoring visits over the last years were:

(1) Issues with informed consent: e.g., investigator signed the informed consent prior to the study participant; (2) protocol deviations: e.g., participants who do not meet the eligibility criteria are included; (3) issues with essential documents: e.g., no delegation log and thus no allocation of study tasks, missing or erroneous standard operating procedures; and (4) issues with Case Report Forms/source data: e.g., missing or erroneous, not readable data entries and inconsistencies.

Our risk-based monitoring experience indicated many GCP deviations [ 5 , 6 ] that reflected the operationalization know-how of the study team. In general, the occurrence of minor findings during on-site monitoring visits in clinical research was high. However, there were no findings regarding safety, and no issues regarding electronic data capture. The collected data were mostly identifiable, recorded contemporaneously, and accurate. Overall, findings did not differ markedly between interventional and observational studies. Unfortunately, findings regarding participant rights, documentation, and essential documents continued to occur.

In our experience, risk-based monitoring indeed reduces monitoring time and efforts. However, in less experienced study teams, reduced monitoring can result in reduced data quality or late detection of protocol deviations. Extensive changes to the study processes or amendments of study protocol or documents after the inclusion of participants will nullify the time and efforts gained by risk-based monitoring. Therefore, even if the risk of a study is low, we recommend planning a monitoring (initiation) visit prior to the start of the study as well as after the inclusion of the first 1-3 participants. This will allow to assess and adapt study processes early on, and thus will increase the quality of the research performance of a study team, in the sense of a “learning research system”.

Indeed, early monitoring visits (including initiation visits) can alert the study team of relevant obstacles, shortcomings or forecast possible problems, give prompt feedback and guidance in GCP. If necessary, it is also possible to train the study team in some aspects of GCP and study related tasks. Furthermore, the monitor can work with the study teams to prepare preventive steps to keep potential risks during the course of the study low. This will improve the conduct of a study, save time, reduce workload and costs and as a result, decrease the number of findings (i.e., GCP deviations) later on.

It is difficult to anticipate what might happen in the future over the course of a study. Independent monitoring is crucial in order to provide operational feedback regarding the study protocol and all other related documents. We, therefore, recommend using monitoring in general as a preventive tool in clinical research. The application of monitoring should already be considered and specified during the planning phase of a study, to maximize the benefits from monitoring activities.

In all, there are many aspects and complexities to GCP. Researchers need to give these issues careful consideration, in order to ensure research integrity and that the safety and rights of all participants are respected.

Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6 (R2). Geneva: ICH (International Conference on Harmonisation); 2016. https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R2__Step_4.pdf .

ECRIN, European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network. Risk-based monitoring toolbox. Paris: ECRIN; 2016. https://www.ecrin.org/tools/risk-based-monitoring-toolbox .

Hurley C, Shiely F, Power J, Clarke M, Eustace JA, Flanagan E, et al. Risk based monitoring (RBM) tools for clinical trials: a systematic review. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;51:15–27.

Article Google Scholar

Brosteanu O, Houben P, Ihrig K, Ohmann C, Paulus U, Pfistner B, et al. Risk analysis and risk adapted on-site monitoring in noncommercial clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2009;6:585–96.

Beever D, Swaby L. An evaluation of risk-based monitoring in pragmatic trials in UK Clinical Trials Units. Trials. 2019;20:556.

von Niederhausern B, Orleth A, Schadelin S, Rawi N, Velkopolszky M, Becherer C, et al. Generating evidence on a risk-based monitoring approach in the academic setting - lessons learned. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:26.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Clinical Trial Unit, Swiss Paraplegic Centre, Nottwil, Switzerland

Inge-Marie Velstra & Angela Frotzler

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Inge-Marie Velstra .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Velstra, IM., Frotzler, A. All research needs to follow the rules set down by Good Clinical Practice. Spinal Cord 58 , 947–948 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0509-4

Download citation

Received : 17 June 2020

Accepted : 19 June 2020

Published : 02 July 2020

Issue Date : September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0509-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Policy & Compliance

- Clinical Trials

Good Clinical Practice Training

All NIH-funded clinical investigators and clinical trial staff who are involved in the design, conduct, oversight, or management of clinical trials can learn about the requirement to be trained in Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

The principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) help assure the safety, integrity, and quality of clinical trials by addressing elements related to the design, conduct, and reporting of clinical trials. GCP training describes the responsibilities of investigators, sponsors, monitors, and IRBs in the conduct of clinical trials. GCP training aims to ensure that:

- the rights, safety, and well-being of human subjects are protected

- clinical trials are conducted in accordance with approved plans with rigor and integrity

- data derived from clinical trials are reliable

Training Options

The policy does not require a particular GCP course or program. Training in GCP may be achieved through a class or course, academic training program, or certification from a recognized clinical research professional organization. NIH also offers GCP training that is free of charge, including:

- Good Clinical Practice Course (NIDA)

- For NIH Researchers, click here

- For NIH Employees, click here

Policy Guidelines & Implementation

Effective January 1, 2017 – NIH expects all NIH-funded clinical investigators and clinical trial staff who are involved in the design, conduct, oversight, or management of clinical trials to be trained in Good Clinical Practice (GCP). Recipients of GCP training are expected to retain documentation of their training. GCP training should be refreshed at least every three years in order to stay up to date with regulations, standards, and guidelines.

- NOT-OD-16-148: Policy on Good Clinical Practice Training for NIH Awardees Involved in NIH-funded Clinical Trials

This page last updated on: July 7, 2022

- Bookmark & Share

- E-mail Updates

- Help Downloading Files

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

- NIH... Turning Discovery Into Health

Good Clinical Practice (GCP) - an alternative, unarticulated narrative

Affiliation.

- 1 Professor and Head, Department of Pharmacology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, 160 012 INDIA.

- PMID: 34730093

- DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2021.064

GCP has become the gold-standard for clinical research; initiated as a guideline pertaining to new drug development, it became a law in many countries, extending its scope to include all research. GCP is an excellent document that outlines the responsibilities of stakeholders involved in clinical research. Widely acclaimed, and deservedly so, it is considered as the "go-to" document whenever questions arise during the conduct of a clinical trial. This article presents another narrative, one that has not been articulated so far. Irrespective of whether we consider GCP as a law or a guideline, it is viewed as an "official" document, without the overt realisation that this was actually an initiative of the pharmaceutical industry, the "masters of mankind". While the stress on documentation and monitoring in GCP was justified, its over-interpretation led to increased costs of clinical trials, with the result that smaller companies find it difficult to conduct the already expensive trials. GCP as an idea is now so entrenched within the scientific community that the real aims which led to its birth and that can be mined from the ICH website, like the need for market expansion, have remained largely unnoticed and undocumented, and are being expressed here.

- Drug Industry*

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- FDA Organization

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research | CDER

Good Clinical Practice

FDA regulates scientific studies that are designed to develop evidence to support the safety and effectiveness of investigational drugs (human and animal), biological products, and medical devices. Physicians and other qualified experts ("clinical investigators") who conduct these studies are required to comply with applicable statutes and regulations. These laws and regulations are intended to ensure the integrity of clinical data on which product approvals are based and to help protect the rights, safety, and welfare of human subjects.

The following resources are provided to help investigators, sponsors, and contract research organizations who conduct clinical studies on investigational new drugs comply with U.S. law and regulations covering good clinical practice (GCP).

General Information

- General Information for Clinical Investigators

- Information and Activities Targeted Toward Specific Audiences and Populations

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs)

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and Protection of Human Subjects in Clinical Trials

- Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Investigators

- FDA Compliance Program 7348.809 - BIMO for Institutional Review Boards

FDA Regulations

- Regulations: Good Clinical Practice and Clinical Trials

Sponsors, Monitors, and Contract Research Organizations

- Guidances and Enforcement Information

- Investigational New Drug Application (IND Regulations) (21 CFR Part 312)

- Regulations for Applications for FDA Approval to Market a New Drug (NDA Regulations) (21 CFR Part 314)

Back to Top

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Heart Views

- v.18(3); Jul-Sep 2017

Guidelines To Writing A Clinical Case Report

What is a clinical case report.

A case report is a detailed report of the symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of an individual patient. Case reports usually describe an unusual or novel occurrence and as such, remain one of the cornerstones of medical progress and provide many new ideas in medicine. Some reports contain an extensive review of the relevant literature on the topic. The case report is a rapid short communication between busy clinicians who may not have time or resources to conduct large scale research.

WHAT ARE THE REASONS FOR PUBLISHING A CASE REPORT?

The most common reasons for publishing a case are the following: 1) an unexpected association between diseases or symptoms; 2) an unexpected event in the course observing or treating a patient; 3) findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease or an adverse effect; 4) unique or rare features of a disease; 5) unique therapeutic approaches; variation of anatomical structures.

Most journals publish case reports that deal with one or more of the following:

- Unusual observations

- Adverse response to therapies

- Unusual combination of conditions leading to confusion

- Illustration of a new theory

- Question regarding a current theory

- Personal impact.

STRUCTURE OF A CASE REPORT[ 1 , 2 ]

Different journals have slightly different formats for case reports. It is always a good idea to read some of the target jiurnals case reports to get a general idea of the sequence and format.

In general, all case reports include the following components: an abstract, an introduction, a case, and a discussion. Some journals might require literature review.

The abstract should summarize the case, the problem it addresses, and the message it conveys. Abstracts of case studies are usually very short, preferably not more than 150 words.

Introduction

The introduction gives a brief overview of the problem that the case addresses, citing relevant literature where necessary. The introduction generally ends with a single sentence describing the patient and the basic condition that he or she is suffering from.

This section provides the details of the case in the following order:

- Patient description

- Case history

- Physical examination results

- Results of pathological tests and other investigations

- Treatment plan

- Expected outcome of the treatment plan

- Actual outcome.

The author should ensure that all the relevant details are included and unnecessary ones excluded.

This is the most important part of the case report; the part that will convince the journal that the case is publication worthy. This section should start by expanding on what has been said in the introduction, focusing on why the case is noteworthy and the problem that it addresses.

This is followed by a summary of the existing literature on the topic. (If the journal specifies a separate section on literature review, it should be added before the Discussion). This part describes the existing theories and research findings on the key issue in the patient's condition. The review should narrow down to the source of confusion or the main challenge in the case.

Finally, the case report should be connected to the existing literature, mentioning the message that the case conveys. The author should explain whether this corroborates with or detracts from current beliefs about the problem and how this evidence can add value to future clinical practice.

A case report ends with a conclusion or with summary points, depending on the journal's specified format. This section should briefly give readers the key points covered in the case report. Here, the author can give suggestions and recommendations to clinicians, teachers, or researchers. Some journals do not want a separate section for the conclusion: it can then be the concluding paragraph of the Discussion section.

Notes on patient consent

Informed consent in an ethical requirement for most studies involving humans, so before you start writing your case report, take a written consent from the patient as all journals require that you provide it at the time of manuscript submission. In case the patient is a minor, parental consent is required. For adults who are unable to consent to investigation or treatment, consent of closest family members is required.

Patient anonymity is also an important requirement. Remember not to disclose any information that might reveal the identity of the patient. You need to be particularly careful with pictures, and ensure that pictures of the affected area do not reveal the identity of the patient.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Akhtar N, Lee L Utilization and complications of central venous access devices in oncology patients. Current Oncology.. 2021; 28:(1)367-377 https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28010039

BD ChloraPrep: summary of product characteristics.. 2021; https://www.bd.com/en-uk/products/infection-prevention/chloraprep-patient-preoperative-skin-preparation/chloraprep-smpc-pil-msds

Chloraprep 10.5ml applicator.. 2022a; https://www.bd.com/en-uk/products/infection-prevention/chloraprep-patient-preoperative-skin-preparation/chloraprep-patient-preoperative-skin-preparation-product-line/chloraprep-105-ml-applicator

Chloraprep 3ml applicator.. 2022b; https://www.bd.com/en-uk/products/infection-prevention/chloraprep-patient-preoperative-skin-preparation/chloraprep-patient-preoperative-skin-preparation-product-line/chloraprep-3-ml-applicator

Website.. 2021; https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/preventinfections/providers.htm

Ceylan G, Topal S, Turgut N, Ozdamar N, Oruc Y, Agin H, Devrim I Assessment of potential differences between pre-filled and manually prepared syringe use during vascular access device management in a pediatric intensive care unit. https://doi.org/10.1177/11297298211015500

Clare S, Rowley S Best practice skin antisepsis for insertion of peripheral catheters. Br J Nurs.. 2021; 30:(1)8-14 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.1.8

Caguioa J, Pilpil F, Greensitt C, Carnan D HANDS: standardised intravascular practice based on evidence. Br J Nurs.. 2012; 21:(14)S4-S11 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2012.21.Sup14.S4

Easterlow D, Hoddinott P, Harrison S Implementing and standardising the use of peripheral vascular access devices. J Clin Nurs.. 2010; 19:(5-6)721-727 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03098.x

Florman S, Nichols RL Current approaches for the prevention of surgical site infections. Am J Infect Dis.. 2007; 3:(1)51-61 https://doi.org/10.3844/ajidsp.2007.51.61

Gorski LA, Hadaway L, Hagle M Infusion therapy standards of practice. J Infus Nurs.. 2021; 44:(S1)S1-S224 https://doi.org/10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396

Guenezan J, Marjanovic N, Drugeon B Chlorhexidine plus alcohol versus povidone iodine plus alcohol, combined or not with innovative devices, for prevention of short-term peripheral venous catheter infection and failure (CLEAN 3 study): an investigator-initiated, openlabel, single centre, randomised-controlled, two-by-two factorial trial [published correction appears in Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Apr 6]. Lancet Infect Dis.. 2021; 21:(7)1038-1048 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30738-6

Gunka V, Soltani P, Astrakianakis G, Martinez M, Albert A, Taylor J, Kavanagh T Determination of ChloraPrep® drying time before neuraxial anesthesia in elective cesarean delivery: a prospective observational study. Int J Obstet Anesth.. 2019; 38:19-24 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.10.012

Ishikawa K, Furukawa K Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia due to central venous catheter infection: a clinical comparison of infections caused by methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible strains. Cureus.. 2021; 13:(7) https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.16607

Loveday HP, Wilson JA, Pratt RJ Epic3: national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infect.. 2014; 86:(S1)S1-70 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6701(13)60012-2

Promoting safer use of injectable medicines.. 2007; https://healthcareea.vctms.co.uk/assets/content/9652/4759/content/injectable.pdf

Standards for infusion therapy. 4th edn.. 2016; https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/Infection-prevention-and-control/Standards-for-infusion-therapy

Taxbro K, Chopra V Appropriate vascular access for patients with cancer. Lancet.. 2021; 398:(10298)367-368 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00920-X

Case Studies

Gema munoz-mozas.

Vascular Access Advanced Nurse Practitioner—Lead Vascular Access Nurse, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust

View articles · Email Gema

Colin Fairhurst

Vascular Access Advanced Clinical Practitioner, University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust

View articles

Simon Clare

Research and Practice Development Director, The Association for Safe Aseptic Practice

View articles · Email Simon

Intravenous (IV) access, both peripheral and central, is an integral part of the patient care pathways for diagnosing and treating cancer. Patients receiving systemic anticancer treatment (SACT) are at risk for developing infections, which may lead to hospitalisation, disruptions in treatment schedules and even death ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021 ). However, infection rates can be reduced and general patient outcomes improved with the evidence-based standardisation of IV practice, and the adoption of the appropriate equipment, such as peripheral IV cannulas, flushing solutions and sterile IV dressings ( Easterlow et al, 2010 ).

Cancer treatment frequently involves the use of central venous catheters (CVCs)-also referred to as central venous access devices (CVADs)—which can represent a lifeline for patients when used to administer all kinds of IV medications, including chemotherapy, blood products and parenteral nutrition. They can also be used to obtain blood samples, which can improve the patient’s quality of life by reducing the need for peripheral stabs from regular venepunctures ( Taxbro and Chopra, 2021 ). CVCs are relatively easy to insert and care for; however, they are associated with potential complications throughout their insertion and maintenance.

One serious complication of CVC use is catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs), which can increase morbidity, leading to prolonged hospitalisation and critical use of hospital resources ( Akhtar and Lee, 2021 ). Early-onset CRBSIs are commonly caused by skin pathogens, and so a cornerstone of a CRBSI prevention is skin antisepsis at the time of CVC insertion. Appropriate antisepsis (decontamination/preparation) of the site for CVC insertion can prevent the transmission of such skin pathogens during insertion, while reducing the burden of bacteria on the CVC exit site ( Loveday et al, 2014 ).

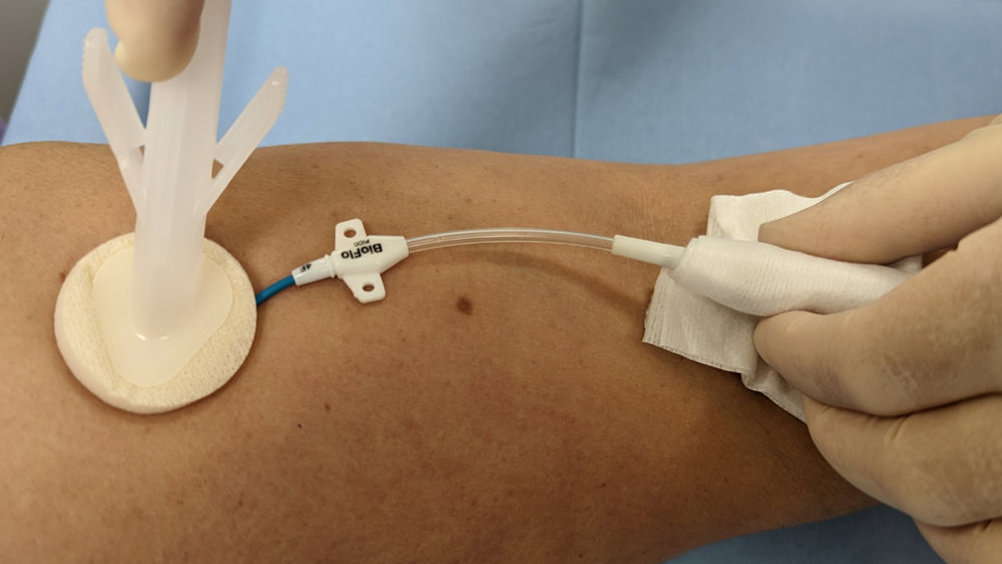

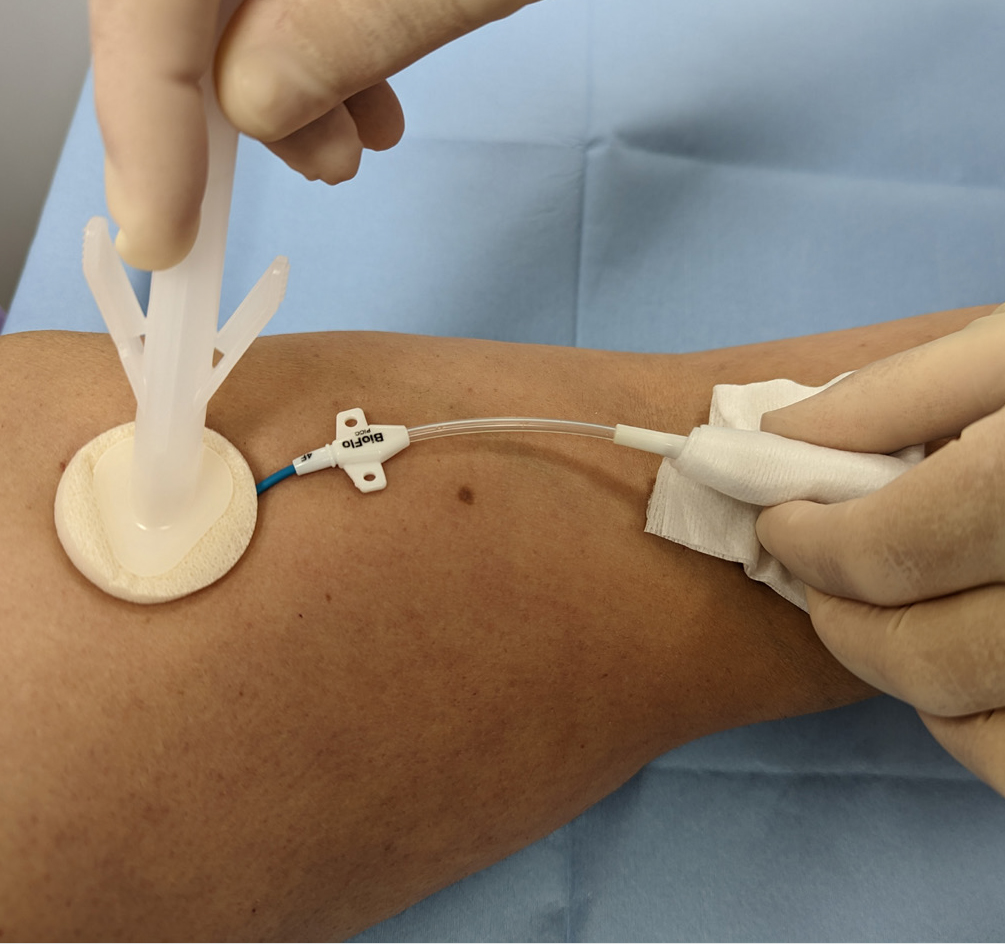

Evidence-based practice for the prevention of a CRBSIs and other healthcare-associated infections recommends skin antisepsis prior to insertion of a vascular-access device (VAD) using a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol solution. This is recommended in guidelines such as epic3 ( Loveday et al, 2014 ), the Standards for Infusion Therapy ( Royal College of Nursing, 2016 ) and the Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice ( Gorski et al, 2021 ). A strong evidenced-backed product such as BD ChloraPrep™ ( Figure 1 ) has a combination of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol that provides broad-spectrum rapid-action antisepsis, while the applicators facilitate a sterile, single-use application that eliminates direct hand-to-patient contact, helping to reduce cross-contamination and maintaining sterile conditions ( BD, 2021 ). The BD ChloraPrep™ applicator’s circular head allows precise antisepsis of the required area, and the sponge head helps to apply gentle friction in back-and-forth motion to penetrate the skin layers ( BD, 2021 ). BD ChloraPrep’s rapidacting, persistent and broad-spectrum characteristics and proven applicator system ( Florman and Nichols, 2007 ) make it a vital part of the policy and protocol for insertion, care and maintenance of CVCs in specialist cancer centres such as the Royal Marsden. Meanwhile, the use of BD PosiFlush™ Prefilled Saline Syringe ( Figure 2 ), a prefilled normal saline (0.9% sodium choride) syringe, is established practice for the flushing regime of VADs in many NHS Trusts.

The following five case studies present examples from personal experience of clinical practice that illustrate how and why clinicians in oncology and other disciplines use BD ChloraPrep ™ and BD PosiFlush ™ Prefilled Saline Syringe in both adult and paediatric patients.

Case study 1 (Andy)

Andy was a 65-year-old man being treated for metastatic colorectal cancer at the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust specialist cancer service, which provides state-of-the-art treatment to over 60 000 patients each year.

Andy had a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placed at the onset of his chemotherapy treatment to facilitate IV treatment. While in situ, PICCs require regular maintenance to minimise associated risks. This consists of a weekly dressing change to minimise infection and a weekly flush to maintain patency, if not in constant use. For ambulatory patients, weekly PICC maintenance can be carried out either in the hospital outpatient department or at home by a district nurse or family member trained to do so. Patients, relatives, carers and less-experienced nurses involved in PICC care (flushing and dressing) can watch a video on the Royal Marsden website as an aide memoir.

Initially, Andy decided to have his weekly PICC maintenance at the hospital’s nurse-led clinic for the maintenance of CVCs. At the clinic, Andy’s PICC dressing change and catheter flushing procedures were performed by a nursing associate (NA), who, having completed the relevant competences and undergone supervised practise, could carry out weekly catheter maintenance and access PICC for blood sampling.

In line with hospital policy, the PICC dressing change was performed under aseptic non-touch technique (ANTT) using a dressing pack and sterile gloves. After removal of the old dressing, the skin around the entry site and the PICC was cleaned with a 3 ml BD ChloraPrep™ applicator, using back-andforth strokes for 30 seconds and allowing the area to air dry completely before applying the new dressing. As clarified in a recent article on skin antisepsis (Clare and Rowley, 2020), BD ChloraPrep™ applicator facilitated a sterile, single-use application that eliminates direct hand-to-patient contact, which help reduce cross-contamination and maintaining ANTT. Its circular head allowed precise antisepsis around the catheter, and the sponge head helped to apply gentle friction in back-and-forth strokes to penetrate the skin layers.

Once the new dressing was applied, the NA continued to clean the catheter hub and change the needle-free connector. Finally, the catheter lumen was flushed with 10 ml of normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) with a pre-filled saline syringe (BD PosiFlush™ Prefilled Saline Syringe). This involved flushing 1 ml at a time, following a push-pause technique, with positive pressure disconnection to ensure catheter patency. The classification of these syringes as medical devices enables NAs and other nonregistered members of the clinical team to support nursing staff with the care and maintenance of PICCs and other CVCs, within local policies and procedures. Using pre-filled syringes can save time and minimise the risk of contamination of the solution ( Ceylan et al, 2021 ).

The use of pre-filled 0.9% sodium chloride syringes facilitates home maintenance of PICCs for patients. When Andy did not need to attend hospital, his PICC maintenance could be performed by a family member. Patients and relatives could access the necessary equipment and training from the day-case unit or outpatient department. Home PICC maintenance is extremely beneficial, not just to providers, but also to patients, who may avoid unnecessary hospital attendance and so benefit from more quality time at home and a reduced risk of hospital-acquired infections. Many patients and relatives have commented on the convenience of having their PICC maintenance at home and how easy they found using the ChloraPrep™ and BD PosiFlush™ Prefilled Saline Syringe ‘sticks’.

Case study 2 (Gail)

Gail was as a 48-year-old woman being treated for bladder cancer with folinic acid, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (FOLOX). She was admitted for a replacement PICC, primarily for continuous cytotoxic intravenous medication via infusion pump in the homecare setting. Her first PICC developed a reaction thought to be related to a sutureless securement device (SSD) anchoring the PICC. The device was removed, but this resulted in displacement of the PICC and incorrect positioning in the vessel (superior vena cava). Now unsafe, the PICC was removed, awaiting replacement, which resulted in a delayed start for the chemotherapy.

A second PICC placement was attempted by a nurse-led CVC placement team, and a line attempt was made in Gail’s left arm. Skin antisepsis was undertaken using a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol solution (ChloraPrep™). A BD ChloraPrep ™ 10 ml applicator was selected, using manufacturer’s recommendations, as per best practice guidance for CVC placement ( Loveday et al, 2014 ) and to comply with local policy for the use of ANTT. The BD ChloraPrep™ applicator allowed improved non-touch technique and helped facilitate good key-part and key-site protection, in line with ANTT ( Clare and Rowley, 2021 ).

The inserting clinician failed to successfully position the PICC in Gail’s left arm and moved to try on the right. On the second attempt, Gail noted the use of BD ChloraPrep™ and stated that she was allergic to the product, reporting a severe skin rash and local discomfort. The line placer informed the Gail that she had used BD ChloraPrep™ on the failed first attempt without issue, and she gave her consent to continue the procedure. No skin reaction was noted during or after insertion of the PICC.

BD ChloraPrep™ has a rapid-acting broad-spectrum antiseptic range and ability to keep fighting bacteria for at least 48 hours ( BD, 2021 ). These were tangible benefits during maintenance of the CVC insertion site, in the protection of key sites following dressing change and until subsequent dressing changes. There are reported observations of clinicians not allowing the skin to fully dry and applying a new dressing onto wet skin after removing old dressings and disinfecting the exit site with BD ChloraPrep™. This has been reported to cause skin irritation, which can be mistaken for an allergic reaction and lead the patient to think that they have an allergy to chlorhexidine. In our centre’s general experience, very few true allergic reactions have ever been reported by the insertion team. Improved surveillance might better differentiate between later reported reactions, possibly associated with a delayed response to exposure to BD ChloraPrep ™ at insertion, and local skin irritation caused by incorrect management at some later point during hospitalisation.

Staff training is an important consideration in the safe and correct use of BD ChloraPrep™ products and the correct use of adhesive dressings to avoid irritant contact dermatitis (ICD). It is worth noting that it can be difficult to differentiate between ICD and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Education and training should be multifaceted (such as with training videos and study days), allowing for different ways of learning, and monitored with audit. Local training in the benefits of using BD ChloraPrep™ correctly have been reinforced by adding simple instructions to ANTT procedure guidelines for CVC insertion and maintenance. Education on its own is often limited to a single episode of training, the benefit of using ANTT procedure guidelines is that they are embedded in a programme of audits and periodic competency reassessment. This makes sure that, as an integral part of good practice, skin antisepsis with BD ChloraPrep ™ is consistently and accurately retrained and assessed.

Gail’s case illustrates the importance of correct application of BD ChloraPrep ™ and how good documentation and surveillance are vital in monitoring skin health during the repeated use skindisinfection products. Care should be taken when recording ICD and ACD reactions, and staff should take steps to confirm true allergy versus temporary skin irritation.

Case study 3 (Beata)

Beata was a 13-year-old teenage girl being treated for acute myeloid leukaemia. Although Beata had a dual-lumen skin-tunnelled catheter in situ, a peripheral intravenous cannula (PIVC) was required for the administration of contrast media for computed tomography (CT) scanning. However, Beata had needlephobia, and so the lead vascular access nurse was contacted to insert the cannula, following ultrasound guidance and the ANTT. After Beata and her mother gave their consent to the procedure, the nurse gathered and prepared all the equipment, including a cannulation pack, single-use tourniquet, skin-antisepsis product, appropriate cannula, PIVC dressing, 0.9% sodium chloride BD PosiFlush ™ Prefilled Saline Syringe, sterile gel, sterile dressing to cover ultrasound probe and personal protective equipment.

Prior to PIVC insertion, a 4x5 cm area of skin underwent antisepsis with a 1.5 ml BD ChloraPrep ™ Frepp applicator, with back-and-forth strokes for 30 seconds, and was allowed to air-dry. The vascular access team prefer to use BD ChloraPrep ™ Frepp over single-use wipes, as the former is faster acting and provides the right volume to decontaminate the indicated area using ANTT ( Clare and Rowley, 2021 ).

Following insertion, the PIVC was flushed with a 10 ml BD PosiFlush ™ Prefilled Saline Syringe syringe, using a pushpause pulsatile technique, with positive pressure disconnection. Local policy recommends the use of pre-filled saline syringes, as they save time and minimise infection risk compared with manually drawn saline flushes ( Ceylan et al, 2021 ). The Trust also permits competent non-registered members of staff to perform PIVC insertion, which is more cost-effective than depending on registered nurses.

In Beata’s case, the team considered the use of BD ChloraPrep™ and BD PosiFlush™ Prefilled Saline Syringe to be essential for the prevention of VAD-associated infections, as well as increasing the quality of nursing care by saving time in the day-case and inpatient settings alike.

Case study 4 (Emma)

Emma, a 43-year-old woman diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, was scheduled for an allogenic stem-cell transplant and associated chemotherapy. To facilitate this, she attended the vascular access service at University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust for the insertion of a triple-lumen skin-tunnelled catheter. This was identified as the best VAD for her needs, because of its longevity, multiple points of access and decreased infection risk compared with other devices, such as PICCs.

This was Emma’s second advanced VAD insertion, having previously received an apheresis line due to poor peripheral venous access, to facilitate the prior stem-cell harvest. She was yet to receive any treatment, and, therefore, no immunodeficiency had been identified prior to the insertion procedure.

Trust policy for skin disinfection prior to the insertion or removal of PICC lines is a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol solution, BD ChloraPrep™. There is an exception for patient history of allergy or sensitivity to BD ChloraPrep™, where 10% povidone iodine is used instead. Emma had received BD ChloraPrep™ before, with no sign allergy or sensitivity, and so the vascular access team decided to use this product again for insertion. BD Chloraprep™ was used, in preference of other skin antisepsis options, due to the applicator’s ability to effectively penetrate the layers of the epidermis, as well as the ability to eliminate direct hand-to-skin contact between the operator and patient ( Clare and Rowley, 2021 ).

Insertion of a skin-tunnelled catheter first requires disinfection of a large area, including the neck and upper chest. Following the manufacturer’s coverage recommendations, a 10.5 ml BD ChloraPrep™ applicator was selected as most suitable to cover an area of 25x30 cm ( BD, 2022 a).

The applicator was activated by pinching the wings to allow the antiseptic solution to properly load onto the sponge. To ensure proper release of the solution, the applicator was held on the skin against the anticipated site of insertion until the sponge pad became saturated. Then, a back-and-forth rubbing motion was undertaken for a minimum of 30 seconds, ensuring that the full area to be used was covered. The solution was then left to dry completely, prior to full-body draping, leaving the procedural area exposed for the procedure. Generally, drying time takes from 30 to 60 seconds, but local policy is not restrictive, as allowing the solution to fully dry is of paramount importance ( Gunka et al, 2019 ). BD Chloraprep™ is effective against a wide variety of microorganisms and has a rapid onset of action ( Florman and Nichols, 2007 ). Therefore, it was felt to be the best option for procedural and ongoing care skin asepsis in a patient anticipated to be immunocompromised during treatment.

It is the normal policy of the Trust’s vascular access service to flush VADs using BD PosiFlush™ Prefilled Saline Syringes with 0.9% sodium chloride. Likewise, BD PosiFlush™ Prefilled Saline Syringes Sterile Pathway (SP) are used to prime all VADs prior to insertion and to check for correct patency once inserted. BD PosiFlush ™ Prefilled Saline Syringe were used in preference of other options, such as vials or bags, due to the absence of requirement for a prescription in the local organisation. They are treated as a medical device and, therefore, can be used without prescription. The advantage of this is that flushes can be administered in a nurse-led clinic, where prescribers are not always available. Aside from the logistical advantages, the use of pre-filled syringes reduces the risk of microbial contamination through preparation error and administration error through correct labelling ( National Patient Safety Agency, 2007 ) In Emma’s case, three BD PosiFlush™ SP Prefilled Saline Syringes were used to check patency and/or ascertain venous location following the insertion of the skin-tunnelled catheter.

In this case, both BD ChloraPrep ™ and BD PosiFlush ™ Prefilled Saline Syringe proved simple to use and helped achieve a successful procedural outcome for the patient.

Case study 5 (Frank)

Frank was a 47-year-old man who had been diagnosed with infective endocarditis following a trans-oesophageal echo. A few days later, to facilitate his planned treatment of 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics to be administered 4-hourly every day, he was referred to the vascular access service for insertion of longterm IV access. To facilitate this administration, the decision was made to place a PICC.

Frank’s referral included a history of illegal intravenous drug use and details of the consequent difficulty the ward-based team had in finding suitable veins to obtain vascular access. His medical history also included infected abscesses in the left groin and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonisation.

First, Frank was administered suppression therapy for MRSA decolonisation. Following this and prior to PICC insertion, the skin antisepsis procedure was undertaken using a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol solution, BD ChloraPrep™, in adherence to Trust policy ( Loveday et al, 2014 ). Specifically, BD ChloraPrep™ applicators are selected for their single-use application. They have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of infectious complications (catheter colonisation and local infection) by 92% compared with 5% povidone iodine (PVI) 69% ethanol ( Guenezan et al, 2021 ). A 3 ml BD ChloraPrep™ applicator was considered suitable to decontaminate an area sufficient for the intended PICC insertion procedure, as recommended by the manufacturer ( BD, 2022 b). It was applied using a back-and-forth motion for a minimum of 30 seconds and left to fully dry ( Loveday et al, 2014 ). Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia’s have a mortality rate of 20-40% and are predominantly caused by VAD insertion ( Ishikawa and Furukawa, 2021 ), and, therefore, the need to reduce this risk was of particular importance for this patient due to the history of MRSA colonisation.

In Frank’s case, the use of BD ChloraPrep™ during the insertion procedure and for each subsequent dressing change episode participated in an uneventful period of treatment. The clinical challenges posed by the patients’ presentation of MRSA colonisation meant the risk of infection was increased but, through correct antisepsis, no adverse events were noted, and the full course of treatment was successfully administered through the PICC.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

19 April 2021. 3. 1- Clinical trials should be conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with good clinical practice (GCP) and applicable regulatory requirement(s). 2- Clinical trials should be designed and conducted in ways that ensure the rights, safety ...

About these Courses. Good Clinical Practice (GCP) includes basic courses tailored to the different types of clinical research. Basic courses provide in-depth foundational training. We also offer completely fresh content in Refresher courses for retraining and advanced learners. Our courses include effective and innovative eLearning techniques ...

Introduction. Health care decision makers need evidence-based medicine to support clinical and health policy choices, 1 and randomized, clinical trials are the highest level of evidence to support these decisions. 2,3 Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines were developed to provide an ethical and scientific quality standard for investigators, sponsors, monitors, and institutional review ...

The Good Clinical Practice (GCP) course is designed to prepare research staff in the conduct of clinical trials with human participants. The 12 modules included in the course are based on ICH GCP Principles and the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) for clinical research trials in the U.S. The course is self-paced and takes approximately six ...

Good Clinical Practice (GCP) is an international standard for the design, conduct, performance, monitoring, auditing, recording, analyses, and reporting of clinical trials. ... case studies, and group exercises, 46 may provide a higher degree of knowledge retention; however, this format would be challenging to administer to large, diverse ...

Welcome to 'Fundamentals of Good Clinical Practice: Recruitment and Trial'! This is the third course in the Clinical Trial GCP series. It is designed to introduce you to the processes, procedures and documentation needed prior, during and after a clinical trial according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP). In Courses One and Two, we explored the ...

Good Clinical Practices and 5 Common GCP Violations in Clinical Studies. Clinical trials are conducted to allow safety and efficacy data to be collected for health interventions, including drugs, biologics, devices, and therapy protocols. These trials can only take place once satisfactory information has been gathered on the quality of the non ...

Spinal Cord 58 , 947-948 ( 2020) Cite this article. All researchers are obliged to follow the very detailed principles/rules of the International Conference on Harmonization—Good Clinical ...

Good Clinical Practice, also known as GCP, is an international set of standards designed to protect patients and ensure the integrity of clinical trials. These regulations are aimed at scientific studies that gather evidence to support the safety and effectiveness of certain investigational drugs for humans and animals, medical devices, and ...

Editorial. Introduction. Case reports and case series or case study research are descriptive studies to present patients in their natural clinical setting. Case reports, which generally consist of three or fewer patients, are prepared to illustrate features in the practice of medicine and potentially create new research questions that may contribute to the acquisition of additional knowledge ...

regulations, preambles, human subject protection, good clinical practice, research, investigation, trial, investigator, IRB, institutional review board

Purpose. The principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) help assure the safety, integrity, and quality of clinical trials by addressing elements related to the design, conduct, and reporting of clinical trials. GCP training describes the responsibilities of investigators, sponsors, monitors, and IRBs in the conduct of clinical trials.

GCP has become the gold-standard for clinical research; initiated as a guideline pertaining to new drug development, it became a law in many countries, extending its scope to include all research. GCP is an excellent document that outlines the responsibilities of stakeholders involved in clinical research. Widely acclaimed, and deservedly so ...

E6 (R2) Good clinical practice. - Scientific. guideline. This document addresses the good clinical practice, an international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording and reporting trials that involve the participation of human subjects. It aims to provide a unified standard for the ICH regions to facilitate ...

To meet these neuroimaging standards, beginning in 2012, we initiated a group practice quality improvement project that included Neuroradiology faculty, clinical instructors, ACGME-accredited fellows, diagnostic radiology residents, and administrative staff with a stated goal of meeting the 20-minute study interpretation metric.

An independent data-monitoring committee that may be established by the sponsor to assess at intervals the progress of a clinical trial, the safety data, and the critical efficacy endpoints, and to recommend to the sponsor whether to continue, modify, or stop a trial. good clinical practice E6(R2) 1.26.

Good Clinical Practice. FDA regulates scientific studies that are designed to develop evidence to support the safety and effectiveness of investigational drugs (human and animal), biological ...

Case-control studies are one of the major observational study designs for performing clinical research. The advantages of these study designs over other study designs are that they are relatively quick to perform, economical, and easy to design and implement. Case-control studies are particularly appropriate for studying disease outbreaks, rare diseases, or outcomes of interest. This article ...