University of Tasmania, Australia

Systematic reviews for health: 1. formulate the research question.

- Handbooks / Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Standards for Reporting

- Registering a Protocol

- Tools for Systematic Review

- Online Tutorials & Courses

- Books and Articles about Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal

- Library Help

- Bibliographic Databases

- Grey Literature

- Handsearching

- Citation Tracking

- 1. Formulate the Research Question

- 2. Identify the Key Concepts

- 3. Develop Search Terms - Free-Text

- 4. Develop Search Terms - Controlled Vocabulary

- 5. Search Fields

- 6. Phrase Searching, Wildcards and Proximity Operators

- 7. Boolean Operators

- 8. Search Limits

- 9. Pilot Search Strategy & Monitor Its Development

- 10. Final Search Strategy

- 11. Adapt Search Syntax

- Documenting Search Strategies

- Handling Results & Storing Papers

Step 1. Formulate the Research Question

A systematic review is based on a pre-defined specific research question ( Cochrane Handbook, 1.1 ). The first step in a systematic review is to determine its focus - you should clearly frame the question(s) the review seeks to answer ( Cochrane Handbook, 2.1 ). It may take you a while to develop a good review question - it is an important step in your review. Well-formulated questions will guide many aspects of the review process, including determining eligibility criteria, searching for studies, collecting data from included studies, and presenting findings ( Cochrane Handbook, 2.1 ).

The research question should be clear and focused - not too vague, too specific or too broad.

You may like to consider some of the techniques mentioned below to help you with this process. They can be useful but are not necessary for a good search strategy.

PICO - to search for quantitative review questions

Richardson, WS, Wilson, MC, Nishikawa, J & Hayward, RS 1995, 'The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions', ACP Journal Club , vol. 123, no. 3, pp. A12-A12 .

We do not have access to this article at UTAS.

A variant of PICO is PICOS . S stands for Study designs . It establishes which study designs are appropriate for answering the question, e.g. randomised controlled trial (RCT). There is also PICO C (C for context) and PICO T (T for timeframe).

You may find this document on PICO / PIO / PEO useful:

- Framing a PICO / PIO / PEO question Developed by Teesside University

SPIDER - to search for qualitative and mixed methods research studies

Cooke, A, Smith, D & Booth, A 2012, 'Beyond pico the spider tool for qualitative evidence synthesis', Qualitative Health Research , vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1435-1443.

This article is only accessible for UTAS staff and students.

SPICE - to search for qualitative evidence

Cleyle, S & Booth, A 2006, 'Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice', Library hi tech , vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 355-368.

ECLIPSE - to search for health policy/management information

Wildridge, V & Bell, L 2002, 'How clip became eclipse: A mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information', Health Information & Libraries Journal , vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 113-115.

There are many more techniques available. See the below guide from the CQUniversity Library for an extensive list:

- Question frameworks overview from Framing your research question guide, developed by CQUniversity Library

This is the specific research question used in the example:

"Is animal-assisted therapy more effective than music therapy in managing aggressive behaviour in elderly people with dementia?"

Within this question are the four PICO concepts :

S - Study design

This is a therapy question. The best study design to answer a therapy question is a randomised controlled trial (RCT). You may decide to only include studies in the systematic review that were using a RCT, see Step 8 .

See source of example

Need More Help? Book a consultation with a Learning and Research Librarian or contact [email protected] .

- << Previous: Building Search Strategies

- Next: 2. Identify the Key Concepts >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 10:17 AM

- URL: https://utas.libguides.com/SystematicReviews

Library Services

UCL LIBRARY SERVICES

- Guides and databases

- Library skills

- Systematic reviews

Formulating a research question

- What are systematic reviews?

- Types of systematic reviews

- Identifying studies

- Searching databases

- Describing and appraising studies

- Synthesis and systematic maps

- Software for systematic reviews

- Online training and support

- Live and face to face training

- Individual support

- Further help

Clarifying the review question leads to specifying what type of studies can best address that question and setting out criteria for including such studies in the review. This is often called inclusion criteria or eligibility criteria. The criteria could relate to the review topic, the research methods of the studies, specific populations, settings, date limits, geographical areas, types of interventions, or something else.

Systematic reviews address clear and answerable research questions, rather than a general topic or problem of interest. They also have clear criteria about the studies that are being used to address the research questions. This is often called inclusion criteria or eligibility criteria.

Six examples of types of question are listed below, and the examples show different questions that a review might address based on the topic of influenza vaccination. Structuring questions in this way aids thinking about the different types of research that could address each type of question. Mneumonics can help in thinking about criteria that research must fulfil to address the question. The criteria could relate to the context, research methods of the studies, specific populations, settings, date limits, geographical areas, types of interventions, or something else.

Examples of review questions

- Needs - What do people want? Example: What are the information needs of healthcare workers regarding vaccination for seasonal influenza?

- Impact or effectiveness - What is the balance of benefit and harm of a given intervention? Example: What is the effectiveness of strategies to increase vaccination coverage among healthcare workers. What is the cost effectiveness of interventions that increase immunisation coverage?

- Process or explanation - Why does it work (or not work)? How does it work (or not work)? Example: What factors are associated with uptake of vaccinations by healthcare workers? What factors are associated with inequities in vaccination among healthcare workers?

- Correlation - What relationships are seen between phenomena? Example: How does influenza vaccination of healthcare workers vary with morbidity and mortality among patients? (Note: correlation does not in itself indicate causation).

- Views / perspectives - What are people's experiences? Example: What are the views and experiences of healthcare workers regarding vaccination for seasonal influenza?

- Service implementation - What is happening? Example: What is known about the implementation and context of interventions to promote vaccination for seasonal influenza among healthcare workers?

Examples in practice : Seasonal influenza vaccination of health care workers: evidence synthesis / Loreno et al. 2017

Example of eligibility criteria

Research question: What are the views and experiences of UK healthcare workers regarding vaccination for seasonal influenza?

- Population: healthcare workers, any type, including those without direct contact with patients.

- Context: seasonal influenza vaccination for healthcare workers.

- Study design: qualitative data including interviews, focus groups, ethnographic data.

- Date of publication: all.

- Country: all UK regions.

- Studies focused on influenza vaccination for general population and pandemic influenza vaccination.

- Studies using survey data with only closed questions, studies that only report quantitative data.

Consider the research boundaries

It is important to consider the reasons that the research question is being asked. Any research question has ideological and theoretical assumptions around the meanings and processes it is focused on. A systematic review should either specify definitions and boundaries around these elements at the outset, or be clear about which elements are undefined.

For example if we are interested in the topic of homework, there are likely to be pre-conceived ideas about what is meant by 'homework'. If we want to know the impact of homework on educational attainment, we need to set boundaries on the age range of children, or how educational attainment is measured. There may also be a particular setting or contexts: type of school, country, gender, the timeframe of the literature, or the study designs of the research.

Research question: What is the impact of homework on children's educational attainment?

- Scope : Homework - Tasks set by school teachers for students to complete out of school time, in any format or setting.

- Population: children aged 5-11 years.

- Outcomes: measures of literacy or numeracy from tests administered by researchers, school or other authorities.

- Study design: Studies with a comparison control group.

- Context: OECD countries, all settings within mainstream education.

- Date Limit: 2007 onwards.

- Any context not in mainstream primary schools.

- Non-English language studies.

Mnemonics for structuring questions

Some mnemonics that sometimes help to formulate research questions, set the boundaries of question and inform a search strategy.

Intervention effects

PICO Population – Intervention– Outcome– Comparison

Variations: add T on for time, or ‘C’ for context, or S’ for study type,

Policy and management issues

ECLIPSE : Expectation – Client group – Location – Impact ‐ Professionals involved – Service

Expectation encourages reflection on what the information is needed for i.e. improvement, innovation or information. Impact looks at what you would like to achieve e.g. improve team communication .

- How CLIP became ECLIPSE: a mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information / Wildridge & Bell, 2002

Analysis tool for management and organisational strategy

PESTLE: Political – Economic – Social – Technological – Environmental ‐ Legal

An analysis tool that can be used by organizations for identifying external factors which may influence their strategic development, marketing strategies, new technologies or organisational change.

- PESTLE analysis / CIPD, 2010

Service evaluations with qualitative study designs

SPICE: Setting (context) – Perspective– Intervention – Comparison – Evaluation

Perspective relates to users or potential users. Evaluation is how you plan to measure the success of the intervention.

- Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice / Booth, 2006

Read more about some of the frameworks for constructing review questions:

- Formulating the Evidence Based Practice Question: A Review of the Frameworks / Davis, 2011

- << Previous: Stages in a systematic review

- Next: Identifying studies >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 10:09 AM

- URL: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/systematic-reviews

Systematic reviews: Formulate your question

- Introduction

- Formulate your question

- Write a protocol

- Search the literature

- Manage references

- Select studies

- Assess the evidence

- Write your review

- Further resources

Defining the question

Defining the research question and developing a protocol are the essential first steps in your systematic review. The success of your systematic review depends on a clear and focused question, so take the time to get it right.

- A framework may help you to identify the key concepts in your research question and to organise your search terms in one of the Library's databases.

- Several frameworks or models exist to help researchers structure a research question and three of these are outlined on this page: PICO, SPICE and SPIDER.

- It is advisable to conduct some scoping searches in a database to look for any reviews on your research topic and establish whether your topic is an original one .

- Y ou will need to identify the relevant database(s) to search and your choice will depend on your topic and the research question you need to answer.

- By scanning the titles, abstracts and references retrieved in a scoping search, you will reveal the terms used by authors to describe the concepts in your research question, including the synonyms or abbreviations that you may wish to add to a database search.

- The Library can help you to search for existing reviews: make an appointment with your Subject Librarian to learn more.

The PICO framework

PICO may be the most well-known model framework: it has its origins in epidemiology and now is widely-used for evidence-based practice and systematic reviews.

PICO normally stands for Population (or Patient or Problem) - Intervention - Comparator - Outcome.

The SPICE framework

SPICE is used mostly in social science and healthcare research. It stands for Setting - Population (or Perspective) - Intervention - Comparator - Evaluation. It is similar to PICO and was devised by Booth (2004).

The examples in the SPICE table are based on the following research question: Can mortality rates for older people be reduced if a greater proportion are examined initially by allied health staff in A&E? Source: Booth, A (2004) Formulating answerable questions. In Booth, A & Brice, A (Eds) Evidence Based Practice for Information Professionals: A handbook. (pp. 61-70) London: Facet Publishing.

The SPIDER framework

SPIDER was adapted from the PIC O framework in order to include searches for qualitative and mixed-methods research. SPIDER was developed by Cooke, Smith and Booth (2012).

Source : Cooke, A., Smith, D. & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research (10), 1435-1443. http://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938 .

More advice about formulating a research question

Module 1 in Cochrane Interactive Learning explains the importance of the research question, some types of review question and the PICO framework. The Library is subscribing to Cochrane Interactive Learning .

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Write a protocol >>

- Last Updated: Mar 28, 2024 1:21 PM

- URL: https://library.bath.ac.uk/systematic-reviews

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Systematic Reviews & Evidence Synthesis Methods

- Formulate Question

- Types of Reviews

- Find Existing Reviews & Protocols

- Register a Protocol

- Searching Systematically

- Supplementary Searching

- Managing Results

- Deduplication

- Critical Appraisal

- Glossary of terms

- Librarian Support

- Video tutorials This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis Boot Camp

Formulate your Research Question

Formulating a strong research question for a systematic review can be a lengthy process. While you may have an idea about the topic you want to explore, your specific research question is what will drive your review and requires some consideration.

You will want to conduct preliminary or exploratory searches of the literature as you refine your question. In these searches you will want to:

- Determine if a systematic review has already been conducted on your topic and if so, how yours might be different, or how you might shift or narrow your anticipated focus.

- Scope the literature to determine if there is enough literature on your topic to conduct a systematic review.

- Identify key concepts and terminology.

- Identify seminal or landmark studies.

- Identify key studies that you can test your search strategy against (more on that later).

- Begin to identify databases that might be useful to your search question.

Types of Research Questions for Systematic Reviews

A narrow and specific research question is required in order to conduct a systematic review. The goal of a systematic review is to provide an evidence synthesis of ALL research performed on one particular topic. Your research question should be clearly answerable from the studies included in your review.

Another consideration is whether the question has been answered enough to warrant a systematic review. If there have been very few studies, there won't be enough qualitative and/or quantitative data to synthesize. You then have to adjust your question... widen the population, broaden the topic, reconsider your inclusion and exclusion criteria, etc.

When developing your question, it can be helpful to consider the FINER criteria (Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethics, and Relevant). Read more about the FINER criteria on the Elsevier blog .

If you have a broader question or aren't certain that your question has been answered enough in the literature, you may be better served by pursuing a systematic map, also know as a scoping review . Scoping reviews are conducted to give a broad overview of a topic, to review the scope and themes of the prior research, and to identify the gaps and areas for future research.

- CEE Example Questions Collaboration for Environmental Evidence Guidelines contains Table 2.2 outlining answers sought and example questions in environmental management.

Learn More . . .

Cochrane Handbook Chapter 2 - Determining the scope of the review and the questions it will address

Frameworks for Developing your Research Question

PICO : P atient/ P opulation, I ntervention, C omparison, O utcome.

PEO: P opulation, E xposure, O utcomes

SPIDER : S ample, P henomenon of I nterest, D esign, E valuation, R esearch Type

For more frameworks and guidance on developing the research question, check out:

1. Advanced Literature Search and Systematic Reviews: Selecting a Framework. City University of London Library

2. Select the Appropriate Framework for your Question. Tab "1-1" from PIECES: A guide to developing, conducting, & reporting reviews [Excel workbook ]. Margaret J. Foster, Texas A&M University. CC-BY-3.0 license .

3. Formulating a Research Question. University College London Library. Systematic Reviews .

4. Question Guidance. UC Merced Library. Systematic Reviews

Sort Link Group

Add / Reorder

Video - Formulating a Research Question (4:43 minutes)

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 12:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/systematicreviews

Memorial Sloan Kettering Library

The physical space of the MSK Library is scheduled to close to visitors on Friday, May 17, 2024. Please visit this guide for more information.

Systematic Review Service

- Review Types

- How Long Do Reviews Take

- Which Review Type is Right for Me

- Policies for Partnering with an MSK Librarian

- Request to Work with an MSK Librarian

- Your First Meeting with an MSK Librarian

- Covidence Review Software

- Step 1: Form Your Team

- Step 2: Define Your Research Question

- Step 3: Write and Register Your Protocol

- Step 4: Search for Evidence

- Step 5: Screen Your Results

- Step 6: Assess the Quality

- Step 7: Collect the Data

- Step 8: Write and Publish the Review

- Additional Resources

Define Your Research Question

A well-developed research question will inform the entirety of your review process, including:

- The development of your inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- The terms used in your search strategies.

- The tool(s) used to assess the quality of included studies.

- The data pulled from the included studies.

- The analysis completed in your review.

- The target journal(s) for your review's publication.

If your question is too broad, you may have trouble completing the review. If your topic is too narrow, there may not be sufficient literature to warrant a review.

How the MSK Library Can Help

One of the first conversations you will have with your MSK librarian will be about your topic.

Your MSK librarian will:

- Work with you to determine whether a systematic review on your topic has been published or planned by searching databases like PubMed , Embase , and Epistemonikos and registries like PROSPERO , Protocols.io , and Open Science Framework (OSF) Registries .

- Ask you for a sample set of relevant publications (also known as seed articles) that you know you want your review to capture. This helps provide a better sense of the scope of your research question. If your topic is too broad or narrow, your MSK librarian can help improve the focus. This sample set will later inform the construction of the search strategy.

Using a Question Framework

- What if my topic does not fit a framework?

PICO is a model commonly used for clinical and healthcare related questions, and is often, although not exclusively, used for searching for quantitively designed studies.

Example question: In elderly patients, does patient handwashing compared to no handwashing impact rates of hospital-acquired infections?

Richardson, W.S., Wilson, M.C, Nishikawa, J. and Hayward, R.S.A. (1995). "The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions." ACP Journal Club , 123(3), A12.

Question framework content adapted from The University of Plymouth Library .

PEO is useful for qualitative research questions.

Example question: In homeless populations, do addiction services impact housing rates?

Moola S, Munn Z, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Lisy K, Tufanaru C, Qureshi R, Mattis P & Mu P. (2015). "Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute's approach." International Journal of Evidence - Based Healthcare, 13(3), 163-9. Available at: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000064.

PCC is useful for both qualitative and quantitative (mixed methods) topics, and is commonly used in scoping reviews.

Example question: What patient-led models of care are used to manage chronic disease in high income countries?

Chronic disease

Patient-led care models

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. "Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews" (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Question framework content adapted from The University of Plymouth Library .

SPIDER is a model useful for qualitative and mixed method type research questions.

Example question: What are young parents’ experiences of attending antenatal education?

Cooke, A., Smith, D. and Booth, A. (2012)."Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis." Qualitative Health Research , 22(10), 1435-1443.

SPICE is a model useful for qualitative and mixed method type research questions.

Example question: Does mindfulness therapy in a counseling service impact the attitudes of patients diagnosed with cancer?

Example question adapted from: Tate, KJ., Newbury-Birch, D., and McGeechan, GJ. (2018). "A systematic review of qualitative evidence of cancer patients’ attitudes to mindfulness." European Journal of Cancer Care , 27(2), 1-10.

ECLIPSE is a model useful for qualitative and mixed method type research questions, especially for questions examining particular services or professions.

Example question: Can cross-service communication impact the support of adults with learning difficulties?

You might find that your topic does not always fall into one of the models listed on this page. You can always modify a model to make it work for your topic, and either remove or incorporate additional elements.

The important thing is to ensure that you have a high quality question that can be separated into its component parts.

- << Previous: Step 1: Form Your Team

- Next: Step 3: Write and Register Your Protocol >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 4:54 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mskcc.org/systematic-review-service

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

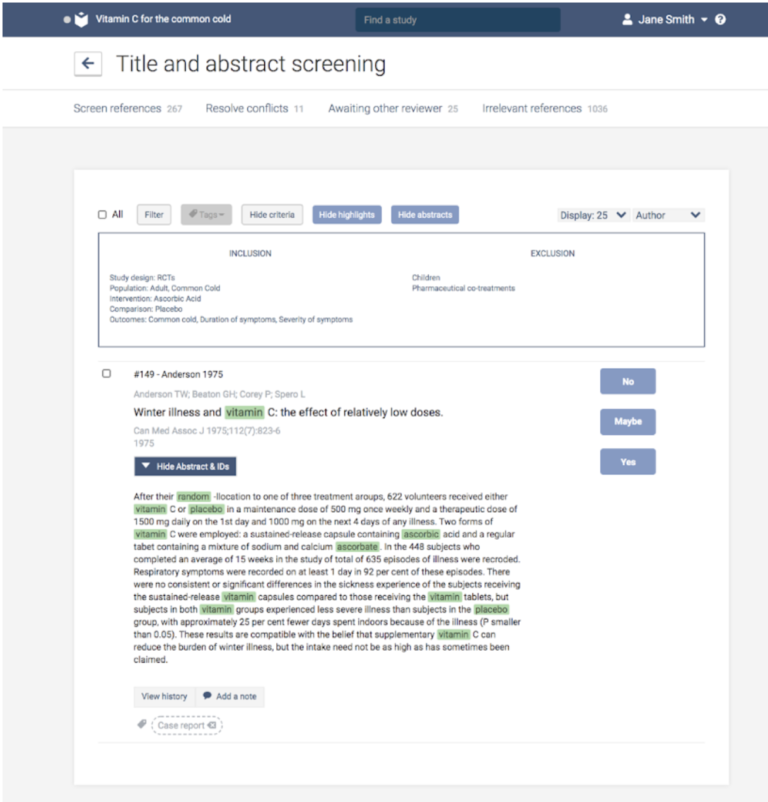

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

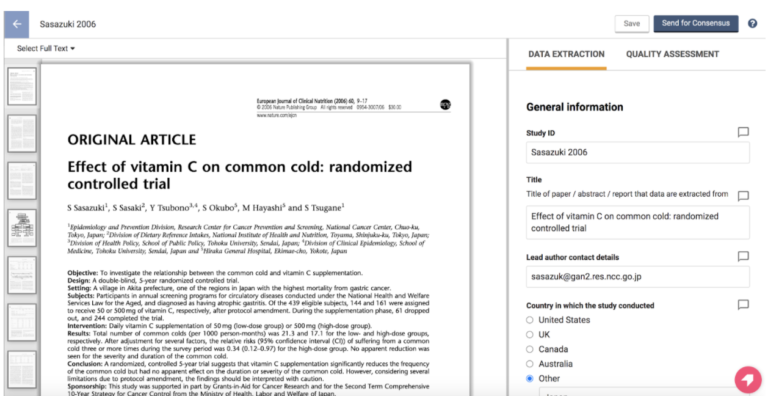

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Systematic Reviews

Develop & Refine Your Research Question

Systematic reviews: develop & refine your research question.

- Knowledge Synthesis Comparison

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Materials in the Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Resources

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Data Extraction Tools

- Minimize Bias

- Critical Appraisal by Study Design

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

A clear, well-defined, and answerable research question is essential for any systematic review, meta-analysis, or other form of evidence synthesis. The question must be answerable. Spend time refining your research question.

- PICO Worksheet

PICO Framework

Focused question frameworks.

The PICO mnemonic is frequently used for framing quantitative clinical research questions. 1

The PEO acronym is appropriate for studies of diagnostic accuracy 2

The SPICE framework is effective “for formulating questions about qualitative or improvement research.” 3

The SPIDER search strategy was designed for framing questions best answered by qualitative and mixed-methods research. 4

References & Recommended Reading

1. Anastasiadis E, Rajan P, Winchester CL. Framing a research question: The first and most vital step in planning research. Journal of Clinical Urology. 2015;8(6):409-411.

2. Speckman RA, Friedly JL. Asking Structured, Answerable Clinical Questions Using the Population, Intervention/Comparator, Outcome (PICO) Framework. PM&R. 2019;11(5):548-553.

3. Knowledge Into Action Toolkit. NHS Scotland. http://www.knowledge.scot.nhs.uk/k2atoolkit/source/identify-what-you-need-to-know/spice.aspx . Accessed April 23, 2021.

4. Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative health research. 2012;22(10):1435-1443.

- << Previous: Review Teams

- Next: Develop a Timeline >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Digital Health Device Collection

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

- What is a Systematic Review?

- Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

A well-developed and answerable question is the foundation for any systematic review. This process involves:

- Systematic review questions typically follow a PICO-format (patient or population, intervention, comparison, and outcome)

- Using the PICO framework can help team members clarify and refine the scope of their question. For example, if the population is breast cancer patients, is it all breast cancer patients or just a segment of them?

- When formulating your research question, you should also consider how it could be answered. If it is not possible to answer your question (the research would be unethical, for example), you'll need to reconsider what you're asking

- Typically, systematic review protocols include a list of studies that will be included in the review. These studies, known as exemplars, guide the search development but also serve as proof of concept that your question is answerable. If you are unable to find studies to include, you may need to reconsider your question

Other Question Frameworks

PICO is a helpful framework for clinical research questions, but may not be the best for other types of research questions. Did you know there are at least 25 other question frameworks besides variations of PICO? Frameworks like PEO, SPIDER, SPICE, and ECLIPS can help you formulate a focused research question. The table and example below were created by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Libraries .

The PEO question framework is useful for qualitative research topics. PEO questions identify three concepts: population, exposure, and outcome. Research question : What are the daily living experiences of mothers with postnatal depression?

The SPIDER question framework is useful for qualitative or mixed methods research topics focused on "samples" rather than populations. SPIDER questions identify five concepts: sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type.

Research question : What are the experiences of young parents in attendance at antenatal education classes?

The SPICE question framework is useful for qualitative research topics evaluating the outcomes of a service, project, or intervention. SPICE questions identify five concepts: setting, perspective, intervention/exposure/interest, comparison, and evaluation.

Research question : For teenagers in South Carolina, what is the effect of provision of Quit Kits to support smoking cessation on number of successful attempts to give up smoking compared to no support ("cold turkey")?

The ECLIPSE framework is useful for qualitative research topics investigating the outcomes of a policy or service. ECLIPSE questions identify six concepts: expectation, client group, location, impact, professionals, and service.

Research question: How can I increase access to wireless internet for hospital patients?

- << Previous: 1. Assemble Your Team

- Next: 3. Write and Register a Protocol >>

- Last Updated: Mar 20, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Systematic Reviews

- What is a Systematic Review?

- 1. Choose the Right Kind of Review

- 2. Formulate Your Question

Formulate Your Question

Inclusion and exclusion criteria, scoping the question.

- 3. Establish a Team

- 4. Develop a Protocol

- 5. Conduct the Search

- 6. Select Studies

- 7. Extract Data

- 8. Synthesize Your Results

- 9. Disseminate Your Report

- Request a Librarian Consultation

Consult With a Librarian

To make an appointment to consult with an HSL librarian on your systematic review, please read our Systematic Review Policy and submit a Systematic Review Consultation Request .

To ask a question or make an appointment for assistance with a narrative review, please complete the Ask a Librarian Form .

A clear, specific, and answerable question is essential to a successful systematic review. A well formulated question will help determine your protocol and search strategy, and help you to find relevant and valid information quickly.

As you develop your question, PICO is a useful tool that can help you define the question's core concepts. There are four components that typically make up a clinical question:

- P atient, problem, or population

- I ntervention

- C omparison intervention (if applicable)

You may also see this framework referred to as PICO(T), with T referring to time.

Here's an example of a clinical question broken down using PICO:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0079444/#ddd00064

The Cochrane Handbook suggests the following factors to consider when using PICO to develop your question:

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Once you have a question, you can use those PICO components to help define your inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria are everything that a study must have to be included in the review.

Exclusion Criteria are anything that would make a study ineligible to be included in the review.

It is important to have these criteria clearly defined before beginning your search to ensure that your selection process is thorough, consistent, and reproducible, and focuses on studies applicable to the research question..

In addition to the factors associated with P opulations, I nterventions and C omparitors, and O utcomes, other parameters along which inclusion criteria could be set include:

- Study design (Randomized controlled trials? Cohort studies? Case-Control Studies? etc.)

- Date (Was it published sufficiently recently? Is the technology used outdated? etc.)

It is not generally possible to formulate an answerable question and determine appropriate inclusion criteria for a review without some knowledge of the existing research relevant to the question. You may need to conduct some preliminary research to help you develop a question that is viable for a systematic review.

Performing preliminary research on a topic can help you:

- Explore the extent and nature of existing literature.

- Identify gaps and uncertainties that might be addressed by a systematic review.

- Understand the terms and concepts used in relevant literature.

- Help identify appropriate parameters for the review (PICO).

- Identify the potential scope of a systematic review.

Your research question needs to be specific enough to get a meaningful conclusion, but broad enough to have enough literature to analyze.

Prior investigation can help you assess whether a systematic review on a given question is justified. It is necessary to check whether there are already existing or ongoing reviews on your topic. Doing so may help you in choosing or refining your question.

Find current/on-going systematic reviews with:

- PROSPERO The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

Find published systematic reviews with:

- PubMed Clinical Queries Systematic reviews appear in the middle column of search results.

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Systematic Review Data Repository The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's repository of systematic reviews.

If you choose to update an existing systematic review , this article can provide some guidance:

- Article: When and how to update an existing systematic review BMJ 2016;354:i3507

- << Previous: 1. Choose the Right Kind of Review

- Next: 3. Establish a Team >>

- Last Updated: Sep 12, 2023 11:57 AM

- URL: https://hslguides.osu.edu/systematic_reviews

Systematic reviews

- Introduction to systematic reviews

- Steps in a systematic review

Formulating a clear and concise question

Pico framework, other search frameworks.

- Create a protocol (plan)

- Sources to search

- Conduct a thorough search

- Post search phase

- Select studies (screening)

- Appraise the quality of the studies

- Extract data, synthesise and analyse

- Interpret results and write

- Guides and manuals

- Training and support

General principles

"A good systematic review is based on a well formulated, answerable question. The question guides the review by defining which studies will be included, what the search strategy to identify the relevant primary studies should be, and which data need to be extracted from each study."

A systematic review question needs to be

You may find it helpful to use a search framework, such as those listed below, to help you to refine your research question, but it is not mandatory. Similarly, you may not always need to use every aspect of the framework in order to build a workable research question.

Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews . Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):380–387.

To help formulate a focussed research question the PICO tool has been created. PICO is a mnemonic for Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. These elements have been highlighted to help define the core elements of the question which will be used in the literature search.

The elements of PICO

Population:.

Who or what is the topic of interest, in the health sciences this may be a disease or a condition, in the social sciences this may be a social group with a particular need.

Intervention:

The intervention is the effect or the change upon the population in question. In the health sciences, this could be a treatment, such as a drug, a procedure, or a preventative activity. Depending on the discipline the intervention could be a social policy, education, ban, or legislation.

Comparison:

The comparison is a comparison to the intervention, so if it were a drug it may be a similar drug in which effectiveness is compared. Sometimes the comparator is a placebo or no comparison.

The outcomes in PICO represent the outcomes of interest for the research question. The outcome measures will vary according to the question but will provide the data against which the effectiveness of the intervention is measured.

- Examples of using the PICO framework (PDF, 173KB) This document contains worked examples of how to use the PICO search framework as well as other frameworks based on PICO.

Not all systematic review questions are well served by the PICO mnemonic and a number of other models have been created, these include: ECLIPSE (Wildridge & Bell, 2002), SPICE (Booth, 2004), and SPIDER (Cooke, Smith, & Booth, 2012).

Wildridge V, Bell L. How CLIP became ECLIPSE: a mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/ management information . Health Info Libr J. 2002;19(2):113–115.

Booth A. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice . Library Hi Tech. 2006;24(3):355-368.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth, A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis . Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443.

Remember: you do not have to use a search framework but it can help you to focus your research question and identify the key concepts and terms that you can use in your search. Similarly, you may not need to use all of the elements in your chosen framework, only the ones that are useful for your individual research question.

- Using the SPIDER search framework (PDF, 134 KB) This document shows how you can use the SPIDER framework to guide your search.

- Using the SPICE search framework (PDF, 134 KB) This document shows how you can use the SPICE framework to guide your search.

- Using the ECLIPSE search framework (PDF, 145 KB) This document shows how you can use the ECLIPSE framework to guide your search.

- << Previous: Steps in a systematic review

- Next: Create a protocol (plan) >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 2:54 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/research-techniques/systematic-reviews

Systematic Reviews: Formulate your question and protocol

- Formulate your question and protocol

- Developing the review protocol

- Searching for evidence

- Search strategy

- Managing search results

- Evaluating results (critical appraisal)

- Synthesising and reporting

- Further resources

This video illustrates how to use the PICO framework to formulate an effective research question, and it also shows how to search a database using the search terms identified. The database used in this video is CINAHL but the process is very similar in databases from other companies as well.

Recommended Reading

- BMJ Best Practice Advice on using the PICO framework.

A longer on the important pre-planning and protocol development stages of systematic reviews, including tips for success and pitfalls to avoid.

* You can start watching this video from around the 9 minute mark.*

Formulate Your Question

Having a focused and specific research question is especially important when undertaking a systematic review. If your search question is too broad you will retrieve too many search results and you will be unable to work with them all. If your question is too narrow, you may miss relevant papers. Taking the time to break down your question into separate, focused concepts will also help you search the databases effectively.

Deciding on your inclusion and exclusion criteria early on in the research process can also help you when it comes to focusing your research question and your search strategy.

A literature searching planning template can help to break your search question down into concepts and to record alternative search terms. Frameworks such as PICO and PEO can also help guide your search. A planning template is available to download below, and there is also information on PICO and other frameworks ( Adapted from: https://libguides.kcl.ac.uk/systematicreview/define).

Looking at published systematic reviews can give you ideas of how to construct a focused research question and an effective search strategy.

Example of an unfocused research question: How can deep vein thrombosis be prevented?

Example of a focused research question: What are the effects of wearing compression stockings versus not wearing them for preventing DVT in people travelling on flights lasting at least four hours.

In this Cochrane systematic review by Clarke et al. (2021), publications on randomised trials of compression stockings versus no stockings in passengers on flights lasting at least four hours were gathered. The appendix of the published review contains the comprehensive search strategy used. This research question has focused on a particular method (wearing compression stockings) in a particular setting (flights of at least 4 hrs) and included only specific studies (randomised trails). An additional way of focusing a question could be to look at a particular section of the population.

Clarke M. J., Broderick C., Hopewell S., Juszczak E., and Eisinga A., 20121. Compression stockings for preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD004002 [Accessed 30th April 2021]. Available from: 10.1002/14651858.CD004002.pub4

There are many different frameworks that you can use to structure your research question with clear parameters. The most commonly used framework is PICO:

- Population This could be the general population, or a specific group defined by: age, socioeconomic status, location and so on.

- Intervention This is the therapy/test/strategy to be investigated and can include medication, exercise, environmental factors, and counselling for example. It may help to think of this as 'the thing that will make a difference'.

- Comparator This is a measure that you will use to compare results against. This can be patients who received no treatment or a placebo, or people who received alternative treatment/exposure, for instance.

- Outcome What outcome is significant to your population or issue? This may be different from the outcome measures used in the studies.

Adapted from: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/systematic-review/protocol

- Developing an efficient search strategy using PICO A tool created by Health Evidence to help construct a search strategy using PICO

Other Frameworks: alternatives to PICO

As well as PICO, there are other frameworks available, for instance:

- PICOT : Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time.

- PEO: Population and/or Problem, Exposures, Outcome

- SPICE: Setting, Population or Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation

- ECLIPS: Expectations, Client Group, Location, Impact, Professionals Involved, Service

- SPIDER: Sample, Phenomenon of interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

This page from City, University of London, contains useful information on several frameworks, including the ones listed above.

Develop Your Protocol

Atfer you have created your research question, the next step is to develop a protocol which outlines the study methodology. You need to include the following:

- Research question and aims

- Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

- search strategy

- selecting studies for inclusion

- quality assessment

- data extraction & analysis

- synthesis of results

- dissemination

To find out how much has been published on a particular topic, you can perform scoping searches in relevant databases. This can help you decide on the time limits of your study.

- Systematic review protocol template This template from the University of Reading can help you plan your protocol.

- Protocol Guidance This document from the University of York describes what each element of your protocol should cover.

Register Your Protocol

It is good practice to register your protocol and often this is a requirement for future publication of the review.

You can register your protocol here:

- PROSPERO: international prospective register of systematic review

- Cochrane Collaboration, Getting Involved

- Campbell Collaboration, Co-ordinating Groups

Adapted from: https://libguides.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/systematic-reviews/methodology

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Developing the review protocol >>

- Last Updated: Sep 12, 2023 5:29 PM

- URL: https://libguides.qmu.ac.uk/systematic-reviews

Systematic Reviews

- Introduction

- Review Process: Step by Step

- 1. Planning a Review

Question Guidance

Research question frameworks, specifying your criteria.

- 3. Standards & Protocols

- 4. Search Terms & Strategies

- 5. Locating Published Research

- 6. Locating Grey Literature

- 7. Managing & Documenting Results

- 8. Selecting & Appraising Studies

- 9. Extracting Data

- 10. Writing a Systematic Review

- Tools & Software

- Guides & Tutorials

- Accessing Resources

- Research Assistance

The first and most important decision in preparing a systematic review is to determine its focus. This is best done by clearly framing the questions the review seeks to answer.

- Systematic reviews should address answerable questions and fill important gaps in knowledge.

- Developing good review questions takes time, expertise and engagement with intended users of the review.

- Cochrane Reviews can focus on broad questions, or be more narrowly defined. There are advantages and disadvantages of each.

- Logic models are a way of documenting how interventions, particularly complex interventions, are intended to ‘work’, and can be used to refine review questions and the broader scope of the review.

- Using priority-setting exercises, involving relevant stakeholders, and ensuring that the review takes account of issues relating to equity can be strategies for ensuring that the scope and focus of reviews address the right questions.

From Chapter 2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . This chapter provides detailed guidance for developing a research question.

- PICO Concepts

- PICO Example

- PECO Example

- Other Search Frameworks

- Selecting a Framework

- Review Typology & Frameworks

As you consider the scope of your research, think about how you will define these concepts:

- Population / Problem: who are you screening? Why?

- Intervention: what are you evaluating? e.g., a treatment, an intervention, etc.

- Comparison: are you comparing this group to another group, e.g. a placebo group?

- Outcome: what are the outcomes? Is there a specific one you are looking at?

Qualitative PICo

- Population / Problem

- Phenomenon of Interest

PICO variations

- PEO: Exposure

- PICOT: Timeframe

- PICOTS: Timeframe, Setting

- PICOS: Study Design , e.g. cohorts or randomized controlled trials.

(From Lackey, M. (2013). Systematic reviews: Searching the literature [PowerPoint slides].

In adults , is screening for depression and feedback of results to providers more effective than no screening and feedback in improving outcomes of major depression in primary care settings ?

- Population / Problem : adults / depression (major)

- Intervention : screening, feedback

- Comparison : none

- Outcome: no particular outcomes specified

(From Lackey, M. (2013). Systematic reviews: Searching the literature [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://guides.lib.unc.edu/ld.php?content_id=258919 )

Table 1. Five paradigmatic approaches and examples for identifying the exposure and comparator in systematic review and decision-making questions.

- dB: decibel ; PECO: population, exposure, comparator, outcome(s).

- a. Cut-off is a broad term referring to thresholds, levels, durations, means, medians, or ranges of exposure.

Morgan, R. L., Whaley, P., Thayer, K. A., & Schünemann, H. J. (2018). Identifying the PECO: a framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes . Environment international , 121 (Pt 1), 1027.

As well as PICO there are many other frameworks for conceptualizing your question:

BeHEMoTh- Behavior of interest, Health context, Exclusions, Models or Theories

- Booth, A., & Carroll, C. (2015). Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: is it feasible? Is it desirable?. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 32(3), 220-235.

ECLIPSE- Expectation/Client group/Location/Impact/Professionals/Service (Evaluating services)

- Wildridge, V., & Bell, L. (2002). How CLIP became ECLIPSE: a mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 19(2), 113-115. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-1842.2002.00378.x

FINER- Feasibility, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant

- Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., & Hulley, S. B. (1988) Conceiving the research question. In S. B. Hulley, & S. R. Cummings SR (Eds), Designing Clinical Research. (pp. 12 - 17). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

SPIDER- Sample/Phenomenon of Interest/Design/Evaluation/Research type (Qualitative studies, especially with samples rather than populations)

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435-1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938

SPICE- Setting/Perspective (or Population)/Intervention/Comparison/Evaluation (Evaluating outcomes of a specific intervention)

- Maryse C. Kok, Hermen Ormel, Jacqueline E. W. Broerse, Sumit Kane, Ireen Namakhoma, Lilian Otiso, Moshin Sidat, Aschenaki Z. Kea, Miriam Taegtmeyer, Sally Theobald, Marjolein Dieleman. (2017) Optimising the benefits of community health workers’ unique position between communities and the health sector: A comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Global Public Health 12:11, pages 1404-1432.

From Monash University Library

From James Cook University Library

From: Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences . BMC medical research methodology , 18 (1), 1-9.

What framework can be applied to our example article?

Dhillon, J., Jacobs, A. G., Ortiz, S., & Rios, L. (2022). A Systematic Review of Literature On the Representation of Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups in Clinical Nutrition Interventions. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmac002

Chapter 3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions , Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis provides detailed guidance for developing a research question.

- Predefined, unambiguous eligibility criteria are a fundamental prerequisite for a systematic review.

- The criteria for considering types of people included in studies in a review should be sufficiently broad to encompass the likely diversity of studies, but sufficiently narrow to ensure that a meaningful answer can be obtained when studies are considered in aggregate.

- Considerations when specifying participants include setting, diagnosis or definition of condition and demographic factors.

Criteria Considerations:

- The population, intervention and comparison components of the question, with the additional specification of types of study that will be included, form the basis of the pre-specified eligibility criteria for the review. It is rare to use outcomes as eligibility criteria...

- Cochrane Reviews should include all outcomes that are likely to be meaningful and not include trivial outcomes. Critical and important outcomes should be limited in number and include adverse as well as beneficial outcomes.

- Review authors should plan at the protocol stage how the different populations, interventions, outcomes and study designs within the scope of the review will be grouped for analysis.

Criteria to Specify:

- Language of publication (ideally this would not be limited)

- Year or year range of publications

- How is the disease/condition defined?

- What are the most important characteristics that describe these people (participants)?

- Are there any relevant demographic factors (e.g. age, sex, ethnicity)?

- What is the setting (e.g. hospital, community, etc)?

- Who should make the diagnosis?

- Are there other types of people who should be excluded from the review (because they are likely to react to the intervention in a different way)?

- How will studies involving only a subset of relevant participants be handled?

- Types of intervention

- Data type/study type

- Study design

- << Previous: 1. Planning a Review

- Next: 3. Standards & Protocols >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/systematic-reviews

- Help and Support

- Research Guides

Systematic Reviews - Research Guide

- Defining your review question

- Starting a Systematic Review

- Developing your search strategy

- Where to search

- Appraising Your Results

- Documenting Your Review

- Find Systematic Reviews

- Software and Tools for Systematic Reviews

- Guidance for conducting systematic reviews by discipline

- Library Support

Review question

A systematic review aims to answer a clear and focused clinical question. The question guides the rest of the systematic review process. This includes determining inclusion and exclusion criteria, developing the search strategy, collecting data and presenting findings. Therefore, developing a clear, focused and well-formulated question is critical to successfully undertaking a systematic review.

A good review question:

- allows you to find information quickly

- allows you to find relevant information (applicable to the patient) and valid (accurately measures stated objectives)

- provides a checklist for the main concepts to be included in your search strategy.

How to define your systematic review question and create your protocol

- Starting the process

- Defining the question

- Creating a protocol

Types of clinical questions

- PICO/PICo framework

- Other frameworks

Research topic vs review question

A research topic is the area of study you are researching, and the review question is the straightforward, focused question that your systematic review will attempt to answer.

Developing a suitable review question from a research topic can take some time. You should:

- perform some scoping searches

- use a framework such as PICO

- consider the FINER criteria; review questions should be F easible, I nteresting, N ovel, E thical and R elevant

- check for existing or prospective systematic reviews.

When considering the feasibility of a potential review question, there should be enough evidence to answer the question whilst ensuring that the quantity of information retrieved remains manageable. A scoping search will aid in defining the boundaries of the question and determining feasibility.

For more information on FINER criteria in systematic review questions, read Section 2.1 of the Cochrane Handbook .

Check for existing or prospective systematic reviews