How to Write an Article for a Magazine: Expert Tips and Tricks

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on Published: June 14, 2023 - Last updated: June 23, 2023

Categories Writing

Magazine writing is a unique form of art that requires writers to carefully blend elements of storytelling, informative research, and reader engagement. Crafting an article for a magazine demands a flair for creative writing and an understanding of the submission process and the specific expectations of the magazine’s audience.

With a clear idea of the subject matter and a strong knack for storytelling, anyone can venture into the world of magazine writing and make a lasting impact on the readers.

The journey of writing a magazine article begins with understanding the fundamentals of magazine articles and their unique characteristics. It requires a thorough understanding of the target market, a well-defined topic, and an unmistakable voice to engage readers.

By focusing on these aspects, writers can create articles that resonate with a magazine’s audience, leading to potential ongoing collaborations and publication opportunities.

Key Takeaways

- Magazine writing involves a blend of storytelling, research, and reader engagement.

- Understanding the target audience and article topic is crucial to success.

- Focusing on writing quality and a unique voice can lead to ongoing publication opportunities.

Understanding Magazine Articles

Types of magazine articles.

Magazine articles can differ significantly from newspaper articles or other forms of writing . Several types of magazine articles include features, profiles, news stories, and opinion pieces. Feature articles are in-depth stories that provide substantial information about a specific subject, often written by freelance writers.

Profiles focus on an individual or organization, showcasing their accomplishments or perspective. News stories are shorter pieces that report timely events and updates, while opinion pieces allow writers to share their viewpoints on relevant matters.

The Purpose of a Magazine Article

The primary purpose of a magazine article is to entertain, inform, or educate its readers in an engaging and visually appealing manner. Magazine writing is crafted with the reader in mind, considering their interests, knowledge level, and preferences.

The tone, structure, and style may vary depending on the target audience and the magazine’s genre. This approach allows for a more flexible, creative, and conversational writing form than news articles or research reports.

Magazine articles are an excellent medium for freelance writers to showcase their writing skills and expertise on specific subjects. Whether they’re writing feature articles, profiles, or opinion pieces, consistency, factual accuracy, and a strong connection with the reader are essential elements of successful magazine writing.

Developing Your Article Idea

Finding a story idea.

Developing a great article idea starts with finding a unique and compelling story. As a freelance writer, you must stay updated on current events, trends, and niche topics that can spark curiosity in the readers.

Browse newspapers, magazine websites, blogs, and social media platforms to stay informed and derive inspiration for your topic. Engage in conversation with others or join online forums and groups that cater to your subject area for fresh insights.

Remember to select a theme familiar to you or one with expertise. This approach strengthens your article’s credibility and offers readers a fresh perspective.

Pitching to Magazine Editors

Once you’ve generated a story idea, the next step is to pitch your concept to magazine editors. Start by researching and building a list of potential magazines or publications suited to your topic. Keep in mind the target audience and interests of each publication.

Instead of submitting a complete article, compose a concise and engaging query letter. This letter should encompass a brief introduction, the main idea of your article, your writing credentials, and any previously published work or relevant experience.

When crafting your pitch, aim for clarity and brevity. Magazine editors often receive numerous submissions, so make sure your pitch stands out.

Tailor the tone of your query letter according to the general style of the target magazine, and consider mentioning specific sections or columns you believe your article would fit.

Patience and persistence are key attributes of successful freelance writers. Always be prepared to pitch your article idea to different magazine editors, and do not hesitate to ask for feedback in case of rejection. Refining and adapting your story ideas will increase your chances of getting published.

Remember to follow the guidelines and protocols established by the magazine or publication when submitting your query letter or article pitches. Also, some magazines may prefer to work with writers with prior experience or published work in their portfolios.

Consider starting with smaller publications or creating a blog to build your credibility and portfolio. With a well-developed article idea and a strong pitch, you’re on the right path to becoming a successful magazine writer.

Writing the Article

The writing process.

The writing process for a magazine article generally involves detailed research, outlining, and drafting before arriving at the final piece. To create a compelling article, identify your target audience and understand their preferences.

This will allow you to tailor your content to suit their needs and expectations. Next, gather relevant information and conduct interviews with experts, if necessary.

Once you have enough material, create an outline, organizing your thoughts and ideas logically. This helps ensure a smooth flow and lets you focus on each section as you write.

Revising your work several times is essential, checking for grammar, punctuation, and clarity. Ensure your language is concise and straightforward, making it accessible to a broad range of readers.

Creating an Engaging Opening

An engaging opening is critical in capturing the reader’s attention and setting the tone for the entire article. Begin your piece with a strong hook, such as an intriguing anecdote, a surprising fact, or a thought-provoking question. This will entice readers to continue reading and maintain their interest throughout the piece.

Remember that different publications may have varying preferences, so tailor your opening accordingly.

Organizing Your Content

Organizing your content is essential in creating a coherent and easy-to-read article. Consider segmenting your piece into sub-sections, using headings to clarify the flow and make the content more digestible. Here are some tips for organizing your content effectively:

- Utilize bullet points or numbered lists to convey information in a simple, organized manner

- Highlight crucial points with bold text to draw readers’ attention

- Use tables to present data or comparisons that may be difficult to express in plain text

As you organize your content, keep your target audience in mind and prioritize readability and comprehension. Avoid making exaggerated or false claims, damaging your credibility and negatively impacting the reader’s experience.

Remember to adhere to the submission guidelines provided by the magazine, as each publication may have different preferences and requirements. Following these steps and maintaining a clear, confident tone can create an engaging and informative magazine article that resonates with your readers.

Polishing Your Article

Proofreading and editing.

Before submitting your article to a magazine, ensure it is polished and error-free. Start by proofreading for grammar, spelling, and punctuation mistakes, making your article look more professional and credible. Using tools like grammar checkers is a good idea, but an experienced writer should also manually review their piece as the software might not detect some mistakes.

Editing your article is crucial, as it helps refine the structure and flow of your writing. Eliminate redundant or unnecessary words and reorganize paragraphs if needed. Consider asking a peer or a mentor to review it for an unbiased perspective.

Keep the magazine’s desired writing style in mind, and adapt your article suitably. For example, a news article may require a concise and informative tone, while a feature in a magazine on pop culture may call for a more conversational and engaging approach.

Using Appropriate Language and Style

To make your article stand out, it is essential to use appropriate language and style. Unlike online publication or social media writing, magazine journalism usually demands a more refined and professional tone. Focus on using a clear, neutral, knowledgeable voice conveying confidence and expertise.

Here are some tips to ensure your article fits the magazine’s desired style:

- Ensure you have a compelling subject line that captures the reader’s attention.

- Depending on the type of article you’re writing, decide if your piece should follow a more scholarly approach, like in a scholarly journal, or a more relaxed, opinion-based style found in lifestyle magazines.

- Use relevant examples to support your points, but avoid making exaggerated or false claims.

- Consider your audience and their interests. Choose the right vocabulary to engage them without making the content too pretentious or complicated.

By carefully proofreading and editing your work and using appropriate language and style, you can ensure your magazine article shines. Remember to stay true to your voice and the magazine’s requirements, and maintain a professional tone.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key components of a magazine article.

A magazine article typically includes a headline, introduction, body, and conclusion. The headline should be striking and attention-grabbing to capture the reader’s interest. The introduction sets the context and tone of the piece while giving the reader a taste of what to expect.

The body of the article is where the main content and message are conveyed, with vital information, examples, and analysis.

The conclusion summarizes the article by summarizing the main points and often providing a call to action or a thought-provoking question.

What is an effective writing style for a magazine article?

An effective writing style for a magazine article should be clear, concise, and engaging. It is essential to cater to the target audience by using language that resonates with them and addressing relevant topics. Keep sentences and paragraphs short and easily digestible, and avoid jargon unless the publication targets industry professionals.

Adopting a conversational tone while maintaining professionalism usually works well in magazine writing.

How should the introduction be written for a magazine article?

The introduction of a magazine article should engage the reader right from the start by grabbing their attention with a hook. This can be an interesting anecdote, a fascinating fact, or a provocative question. The introduction should also establish the flow of the rest of the article by providing brief context or outlining the piece’s structure.

What are the best practices for structuring a magazine article?

The structure of a magazine article should be well-organized and easy to follow. This often means using subheadings, bullet points, or numbered lists to break up the text and emphasize important content. Start with the most important information, then move on to supporting details and background information. Maintain a logical, coherent flow between paragraphs, ensuring each section builds on the previous one.

How can I make my magazine article engaging and informative?

To make a magazine article engaging and informative, focus on finding the right balance between providing valuable information and keeping the reader entertained. Use anecdotes, personal stories, and real-life examples to make the content relatable and genuine. When applicable, include engaging visuals (such as photos or illustrations), as they aid comprehension and make the article more appealing. Finally, address the reader directly when possible, making them feel more involved in the narrative.

What are some useful tips for editing and proofreading a magazine article?

When editing and proofreading a magazine article, focus on the bigger picture, such as organization and flow. Ensure that the structure is logical and transitions are smooth and seamless. Then, move on to sentence-level editing, examining grammar, punctuation, and style consistency. Ensure that redundancies and jargon are eliminated and that the voice and tone match the target audience and publication. Lastly, proofread for typos and errors, preferably using a fresh pair of eyes or a professional editing tool.

CURATE YOUR FUTURE

My weekly newsletter “Financialicious” will help you do it.

In This Post:

How to write an article for a magazine.

Pitching a magazine is a whole other beast. When you land a print placement, however, you'll score major credibility points as a writer or industry expert.

Writing an article for your local newspaper, trade magazines, or national magazines is simpler than you think. But simple doesn’t mean easy.

Freelance writers and industry leaders alike want to land a feature article in a print publication, because magazine writing projects authority and expertise. Media publications often reserve their print edition for the best magazine articles, and a features editor or managing editor will be highly selective with which freelance writers they tap for various article opportunities.

Key Takeaways

- Magazine and newspaper bylines are considered very reputable, since these publications have limited space.

- The timing of your pitch is important, as magazines are produced weeks or even months in advance.

- It's good to be on editors' radar, as they often are shuffling an issue up until the 11th hour, and may want to assign you a piece with quick turnaround to fill a hole.

It’s not just the high quality of the article that makes print pitching different. In magazine journalism , brands often put their issues together months in advance to ensure they’re printed, shipped, and sold on schedule.

In addition to pitching a good magazine article, you also need to send your query letter at the right time in the magazine production process before you start writing. Newspaper articles don’t require as long of a lead time. It all depends on the publication’s submission guidelines.

Related: How to Pitch an Article: 72 Outlet How-Tos

If you’d love to one day write an opinion article, pen a personal essay, or just get more freelance writing jobs with popular magazines, here is what to keep in mind in magazine writing.

Writing for Magazines: A Coveted Byline

Before the internet, media was mainly delivered through print journalism. A freelance writer or aspiring magazine writer would send a query letter to the editor, and magazine editors would decide which magazine articles to pursue, based not only on the article ideas themselves, but also how well they balance one another, based on personal experience.

In print, there is a finite amount of space on the page. In contrast, websites can publish all the articles — they just create a new URL for every article — so the constraint is editor and writer labor, not lack of space or word count. Article placement in a magazine has greater merit and is considered more valuable, even if it’s a local magazine.

Important : It can be tough to pitch a big feature story right out of the gate. Consider pitching a smaller story in the 700-1,200 word range first to build rapport with an editor.

Many of today’s magazines have been around for decades, if not longer, and they’ve built up a track record for editorial quality and influence. We assume that, if someone has written for a reputable magazine or national publications for a particular topic, they are a skilled freelance writer.

In our digital age, many of the most established brands continue to publish a physical magazine, even if the magazine’s readership has declined, because it cements their status as an influential publication. Often, if you write a magazine article, it will also be used online.

This was the case for me when writing an article for OUT magazine. My entire article was accepted, and received a two-page spread in the mag, but it was also published as a post online.

Pro tip: acquire physical copies of your placements so you can document them and use them online, ethically.

How to Pitch a Magazine in 3 Steps

Pitching a physical magazine is similar to other pitching efforts. The single most important factor to a winning pitch is that it’s relevant to the magazine’s target audience. The following three steps will help you ensure your pitch is on point every time; even if your pitch isn’t accepted, editors keep an eye on staff writers and other writers who consistently send relevant pitches, and eventually you will see progress.

Step 1: Research Current and Upcoming Magazine Topics

Read the magazine! What you think a magazine covers based on what you read ten years ago may not be what the outlet covers at all anymore. Browse both the publication’s website and the physical magazine itself to get a sense of their writing and what the brand is currently covering. Look at the news articles and writing styles.

Additionally, for physical magazines, it’s worth your time to poke around online for either a media kit or an editorial calendar . These kits are sales PDFs a magazine makes publicly available to attract prospective advertisers. The kit comes out in the fall or winter each year for the upcoming year, and lists the planned theme of every issue. This can be helpful intel when pitching big publications.

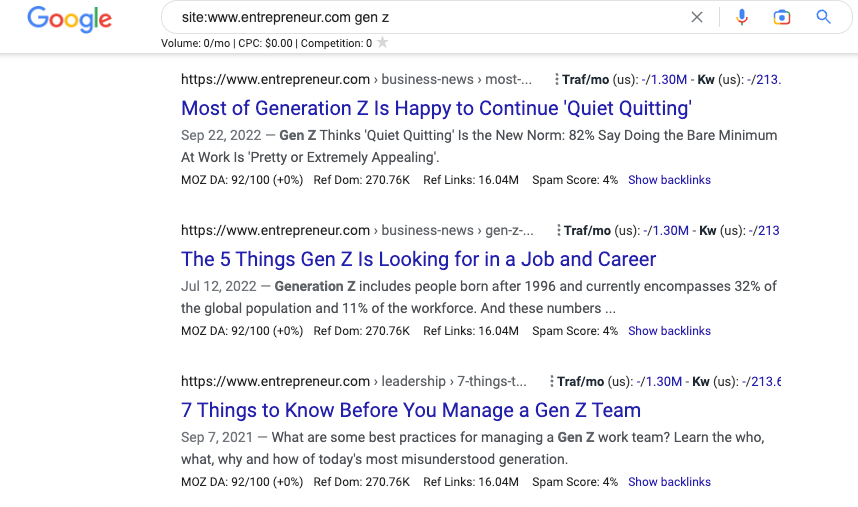

To see what the online version of a brand has previously covered, you can do a web search on Google for that specific site. Start your search with “site:www.outletdomain.com”, then search a topic. In this example, I searched past coverage of Gen Z on Entrepreneur’s website.

The "site:" command in a Google search query will let you filter search results to a particular website.

Knowing an outlet will help you tailor your article pitch to fit the voice, style, and format of the target publication.

Step 2: To Locate Gatekeepers, Find a Masthead

Now comes the tricky part: pitching the editor or decision-maker who oversees print coverage. Luckily, most magazines’ editors and other personnel responsible for bringing a magazine to life will be credited in both the physical issue and online. This list is called a masthead.

A major magazine will engage many writers and other contractors to bring an issue to life, but the staff who are listed on the masthead are almost always directly involved in the production process. This is helpful research material.

For example, searching “Allure masthead” led me directly to their digital masthead page.

The Allure masthead. Screenshot captured November 1, 2022.

From the masthead, do some digging on where these different editors are hanging out outline. Are they on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Instagram? Are they writing articles for magazines as well? What stories are they currently publishing? Also track down their email address.

Step 3: Craft a Strong, Print-Specific Pitch

In print article pitching, every word needs to earn its way onto the page. Your article pitch should have a compelling idea and a fresh perspective; specify whether you want to be considered for print publication, online publication, or both.

Most PR pitches are templates, press releases, or cookie-cutter stock pitches. The key to getting momentum in an article pitch is to hook the editor or journalist in the first couple of sentences. Indicate that your article pitch is not a stock pitch, and make a case for why this article is a perfect fit for them.

Pitch Your Next Magazine Article Today

Article pitching can feel overwhelming at first, but at the end of the day, story ideas just like yours are what make it to newsstands and get read by millions. Remain pleasantly persistent, and eventually your pitching efforts will pay off.

Thanks For Reading 🙏🏼

Keep up the momentum with one or more of these next steps:

📣 Share this post with your network or a friend. Sharing helps spread the word, and posts are formatted to be both easy to read and easy to curate – you'll look savvy and informed.

📲 Hang out with me on another platform. I'm active on Medium, Instagram, and LinkedIn – if you're on any of those, say hello.

📬 Sign up for my free email list. This is where my best, most exclusive and most valuable content gets published. Use any of the signup boxes on the site.

🏕 Up your writing game: Camp Wordsmith® is a free online resources portal all about writing and media. Get instant access to resources and templates guaranteed to make your marketing hustle faster, better, easier, and more fun. Sign up for free here.

📊 Hire me for consulting. I provide 1-on-1 consultations through my company, Hefty Media Group. We're a certified diversity supplier with the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce. Learn more here.

Welcome to the blog. Nick Wolny is a professional writer and editor based in Los Angeles.

- Good Writing

- Revising & Rewriting

- Nonfiction Writing

- Academic Writing

- Travel Writing

- Literary Agents

- Getting Published

- Fiction Writing

- Self-Publishing

- Marketing & Selling Books

- Building a Blog

- Making Money Blogging

- Boosting Blog Traffic

- Online Writing

- eZine Writing

- Making Money Online

- Non-Fiction Writing

- Magazine Writing

- Pitching Query Letters

- Working With Editors

- Professional Writers

- Newspaper Writing

- Making Money Writing

- Running a Writing Business

- Privacy Policy

11 Most Popular Types of Articles to Write for Magazines

- by Laurie Pawlik

- September 4, 2023

- 31 Comments

Want to write for magazines? This list includes feature stories, roundups, profiles, research shorts, human interest, how-to articles and more. You’ll be surprised by how many types of online and print magazine articles you can write! Whether you’re an aspiring freelance writer or an established author you’ll find lots of ideas in this list.

Learning about the different types of magazine articles is one thing. More important is finding courage to write boldly and the strength to keep pitching ideas to editors! May you get published again and again. And, may you prepare yourself to do the work now — before the day ends and you lose your momentum.

The most important thing to remember when you’re looking for different types of magazine articles to write is your audience. Learn how to slant your writing to the target audience, publisher, and editor of the magazine or publication. Books like Writer’s Market: The Most Trusted Guide to Getting Published – are essential to your success. They reveal details and information for freelance writers that you won’t find online.

“You can’t sit in a rocking chair with a lily in your hand and wait for the Mood,” writes author Faith Baldwin in The Writer’s Handbook . “You have to work. You have to work hard and unremittingly, and sacrifice a great deal; and when you fall at, or fail to clear, an obstacle (usually an editor), you have to pick yourself up and go on.”

A crucial part of earning money as a freelance writer is knowing what to work hard on. Learning about the different types of magazine articles is an excellent way to start a freelance writing career, or even boost a faltering author’s yearly income. If you’re serious about selling your writing and making money writing, you need to be constantly learning about writing, getting published, and working with editors.

“Two types of articles continue to dominate the changing field of magazine publishing,” writes Nancy Hamilton in Magazine Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide to Success . “The personality profile and the how-to story with its self-help variant. Together, they account for an estimated 72% of magazine feature material.”

11 Different Types of Magazine Articles

I’ve been published in several different magazines (such as Reader’s Digest, Chatelaine, Women’s Health and More ) and have written each one of these different types of magazine articles…except for the exposé. My favorite is writing research shorts for magazines – but they are just that ( short ) and thus don’t pay much.

As you read through the following types of articles, think about which one you most like to read. This will help you decide what type of article to research and write. The best writing comes from writers who are enjoying their work and passionate about their topic, so don’t hesitate to choose the project that lights your fire.

1. “How To” Articles

“Easily the most popular and the shortest and easiest to write, the how-to article with its self-help variant gives instructions for how to do or be something or how to do it better,” writes Hamilton in Magazine Writing .

“How to” articles:

- Make a rousing promise of success

- Describe what you need in easy to follow instructions

- Give step-by-step directions (sometimes with subtitles)

- Include shortcomings or warnings

- Tell how to locate supplies

- Give proofs and promises

- Make referrals to other sources

Examples of “how to” articles are: “How to Write Magazine Articles That Editors Love to Publish” or “How Freelance Writers Earn a $100,000 Every Year” or How to Think Like a Magazine Editor – 8 Tips for Writers . “How to” articles are my favorite type of feature articles; they simply tell readers how to do something.

Tip for freelance writers: Some magazine or newspaper editors require writers to submit their own photos for how-to articles. Before you accept an assignment from an editor, ask what their photo policy is.

2. Profile and Interview Articles

This popular type of article describes a contemporary or historical person – but a profile doesn’t have to be about a human being! Animals, communities, nations, states, provinces, companies, associations, churches can all be profiled (but not necessarily interviewed).

Personality profiles and interview articles:

- Have different definitions. In a personality profile, you use additional sources, such as friends, family, kids, neighbors, colleagues. In an interview, you talk to the source him or herself – preferably in person.

- Can have a theme or focus.

- Can be presented as a “Q & A” or a written article.

- Require strong interviewing and perception skills for the “best” information

Examples of profiles or interview articles are: “The Real Natalie Goldberg and Her Real Writing Career” or “Anne Lamott Shares Her Secrets for Writing Different Types of Magazine Articles.” Profiles and interview are two different types of magazine articles to write.

About this type of magazine article Hamilton says, “The most successful personality profile allows the reader to experience the story directly without having to filter that experience through the ‘I’ of an unknown writer. Despite this common-sense perspective, many magazines today prefer the ‘I’ approach for personality profiles.” Why? Because most editors want to encourage a personal relationship between the magazine and the reader by addressing them personally.

3. Informative or Service Articles

Informative articles are also know as “survey articles.” They often offer information about a specific field, such as sports medicine, health writing, ocean currents, politics, etc. Service articles are similar, but often used as shorter fillers. Service articles offer a few pieces of good advice or tips, but aren’t usually long or involved.

Informative or service articles:

- Focus on one unique aspect, or the “handle”

- Describe what-to, how-to, when-to, why-to, etc.

- Answer the journalist’s who, what, when, where, why, and how questions

- Can end with a “how-to” piece as a sidebar

Examples of this type of magazine article include: “How to Write Query Letters for Magazines” or “ 10 Magazine Writing Tips From a Reader’s Digest Editor ” or “11 Types of Magazine Articles to Write for Magazines.”

The informative or service article is similar to the how-to type of magazine article. I’d love to write a service article for the SPCA, but I’m too busy with my blogs to pitch article ideas to editors.

4. The Alarmer-Exposé

“A Reader’s Digest staple, the alarmer-exposé is designed to alert and move the reader to action,” writes Hamilton in Magazine Writing . “Well-researched and heavy with documentation, this type of magazine article takes a stance and adopts a particular point of view on a timely and often controversial issue. Its purpose is to expose what’s wrong here.”

- Shocks or surprises readers

- Includes statistics, quotes, anecdotes

- Can range from how extension cords can kill to new info on Watergate

“This article is best written by an established writer who is skilled in reporting an issue and building a case without flagrant – and apparent – bias,” says Hamilton.

Examples of an exposé magazine article are: “Stephen King’s Ghostwriter Reveals Secret Writing Career” or “95% of Natalie Goldberg’s Writing is From a Ghostwriter!” Those aren’t actual feature articles that were written by freelance writers – they’re just examples of the different types of magazine articles.

5. Human Interest Magazine Articles:

- Usually start with an anecdote

- Are often chronologically organized

Examples of human interest magazine articles are: “Anne Lamott Shares Her Secrets to Success as a Single Mother and Bestselling Author” or “Mark Twain’s Great-Granddaughter Discovers a Brand New Type of Magazine Article.” This type of feature article interests the majority of readers of a specific, niched magazine.

People is currently one of the most popular magazines on the market, and it specializes in this type of article. If you find someone who has done or experienced something extraordinary – and if your writing skills are pretty good – you might consider sending a query letter to the editors at People .

6. Essay, Narrative, or Opinion Articles

This is my least favorite type of magazine article or blog post to write! I’m not a big writer of personal stories (nor do I like to read autobiographies, biographies, or personal blogs). I’d much rather encourage readers by sharing information – such as these 11 different types of articles to write magazines 🙂

Essay, narrative, or opinion articles:

- Usually revolve around an important or timely subject (if they’re to be published in a newspaper or “serious” magazine)

- Are harder to sell if you’re an unknown or unpublished writer

- Can be found on blogs all over the internet

Here’s some great writing advice from Hamilton: “The narrative uses fiction technique to recreate the tension, the setting, the emotion – the drama – of something that actually happened. The article must have implications and ramifications that are meaningful to a reader. It must be relevant to what’s going on today – one event that relates to the larger whole.”

Examples of this type of magazine article are: “What I Think of Natalie Goldberg’s Decision to Retire From Her Writing Career” or “Anne Lamott’s Most Famous Writing Mistakes.”

If you feel overwhelmed with all these types of magazine articles, read How to Write When You Have No Ideas .

7. Humor or Satire Articles

Humor or satire articles are really hard to write. I just read today – in the University of Alberta’s Trail magazine – that it takes the Simpsons’ writers and staff SIX MONTHS to write and produce a single episode! That’s because humor writing seems easy and fast, but it’s actually the hardest type of writing to learn…not to mention master.

Humor or satire articles:

- Usually have a specific audience, such as the readers of The Onion

- Are usually written on spec (that is, you submit the whole article before the editors or publishers will accept it for publication in the magazine)

Examples of humor or satire articles might include: “Ode to Stephen King’s Typewriter” or “What Margaret Laurence Ate the Day She Started Writing Articles for Magazines.”

8. Historical Articles

What can I say? A historical article describes a moment in time. Or an epoch. Or an era. Or an eon.

Historical articles:

- Reveal events of interest to millions (which means at least one of my examples wouldn’t work as this type of article)

- Focus on a single aspect of the subject

- Are organized chronologically

- Tell readers something new

- Go beyond history to make a current connection

Examples of this type of magazine article include: “The Typewriter Mark Twain First Used” or “How Freelance Writers Submitted Articles Before Typewriters Were Invented” or “How the Use of the Word ‘Tweet’ Evolved From 2005 to Now.”

9. Inspirational Magazine Articles

- Describe how to feel good or how to do good things

- Can describe how to feel good about yourself – this type of article can work for anyone from writers to plumbers to pilots

- Offer a moral message

- Focus on the inspirational point

Examples of different types of inspirational articles for magazines are: “How You Can Change the World With Your Writing Career” or “13 Tips to Improve Your Writing Confidence.”

This is probably my second most favorite type of feature article to write. It’s definitely the post I write most often on my Blossom blogs!

10. Round-Up Magazine Articles

- Gather a collection from many sources

- Focus on one theme

- Offer quotations, opinions, statistics, research studies, anecdotes, recipes, etc.

The Round-Up was one of my favorite types of magazine articles to write when I was freelancing. Examples of round up articles are: “ 12 Fiction Writing Tips From Authors and Editors ” or “1,001 Types of Articles to Write for Magazines.” I enjoy writing round-ups because I can squeeze in lots of information in 1,000 words.

11. Research Shorts

- Describe current scientific information

- Are usually less than 250 words long

- Are often written on spec (at least by me)

- Are fast, effective ways to earn money as a freelance writer – if you can find the right markets

Research Shorts for the “Front of the Book” are those little blurbs of scientific research you see at the beginning of many magazines. Examples of these types of articles for magazines include: “How Alliteration Affects Your Memory” or “What Anne Lamott’s Writing Does to Your Brain Waves.”

Shorts aren’t really a type of magazine article, but they’re a great way to get your foot in the door and learn what articles editors will pay to publish .

Types of Magazine Articles You Can Write

In 11 Most Popular Articles to Write for Magazines | Tips for Freelance Writers I share different types of articles to write, to help you get published in the right magazine.

My list includes feature length stories, roundups, personality profiles, research shorts, human interest pieces, and “how to” articles. I also included examples of magazines that publish each type of article. Whether you’re an aspiring freelance writer or an established author you’ll find lots of ideas in this list.

Here’s a tip from bestselling author Natalie Goldberg about being a successful writer: “I hear people say they’re going to write. I ask, when? They give me vague statements,” she writes in Thunder and Lightning: Cracking Open the Writer’s Craft . “Indefinite plans get dubious results.”

What are your writing goals, and how will you achieve them? Have you made a specific plan? After you read through these different types of articles to write for magazines, create goals for yourself.

Writer’s Digest Magazine

Writer’s Digest Magazine is my favorite periodical about writing; a subscription is both motivating and informative. The more you learn about freelance writing – including the business of writing – the easier it’ll be to remember the different types of magazine articles you can write for magazines.

If you want to be a freelance writer, you have to do more than just learn about the different types of magazine articles to write for magazines. You need to research professional writing organizations, learn how to write query letters for editors, and where to pitch your ideas.

If you have any thoughts or questions about writing these types of feature articles for magazines and other publications, feel free to share below.

Comments Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of new posts by email.

31 thoughts on “11 Most Popular Types of Articles to Write for Magazines”

What if you wrote a catchier title? I don’t want to tell you how to run your Successful Writers blog, but suppose you added something to possibly grab folk’s attention? I mean 11 Popular Magazine Articles That Editors Love to Publish is a little vanilla. You ought to peek at Yahoo’s home page and see how they create post titles to get viewers to click. You might try adding a video or a related pic or two to get readers interested about everything’ve got to say. Just my opinion, it could make your Successful Writers blog a little livelier.

Thank you , Laurie! I am just starting my online magazine UpMixed in a month so these tips are going to help me.

“By the time I was fourteen the nail in my wall would no longer support the weight of the rejection slips impaled upon it. I replaced the nail with a spike and went on writing.” ~ Stephen King

Most writers starts their publishing journey the wrong way. They want to start big. They want a book contract, a speaking tour, and all-around international fame and notoriety. But that’s not how this thing works. we need to start small. This is a blessing in disguise, actually, as you are probably not that good when you are just beginning. You need time to practice writing articles for magazines that are of publishable quality.

Dear Newbie Magazine Writer,

Here’s an article that will give you a few pointers:

How to Write a Query Letter and Get Your Article Published https://www.theadventurouswriter.com/blogwriting/how-to-write-query-letters-for-magazine-articles/

Let me know what happens after you pitch your query to the magazine editor! It sounds like a winner 🙂

I have a brilliant idea for an article, and I believe it’s perfect for the publication I have in mind. I just don’t know how to write a query letter to a magazine. Can you help me by giving me a formula or structure on how to pitch my idea to the editor? I haven’t done much research or reading, but I found this article on the different types of magazine articles helpful. Thank you for any direction you can offer!

Nice ☺☺☺ would give some topics of Articles. ..?

I also need some topics

Dear Lokesh,

Your first step is to learn how to write English really, really well. Take ESL courses, read books, practice writing, do whatever it takes to learn how to write English.

At the same time, you need to learn the business of freelance writing. It’s a career, not a hobby. It takes time, dedication, and energy.

Here’s one place to start:

How to Become a Freelance Writer https://www.theadventurouswriter.com/blogwriting/how-to-be-a-freelance-writer/

Read books about freelance writing, pitching articles to editors, and becoming a journalist. Rolling Stone is an amazing magazine and it’s difficult to get published in it — but you CAN do it!

Take it one step at a time. Keep learning English – you’re doing great so far – and keep reading articles, blogs, and books about becoming a freelance writer for magazines.

You can do it! Remember that nothing worth having is easy. Everything good in life takes hard work. If it was easy, everyone would do it.

Blessings, Laurie

Thanks for the help Ressa, I am just a student and I confuse for my future because every time I thinking a new Idea like what I want or which field is good for me and finnaly I diciede what I want….!! Article writer and for me I think it’s a very good choice but still I little confused that how I write my first artical, actually the problem is that my mind is confuse that what is a good topic for me…. cause I need a very new or u can say a “fresh” topic which is never be write buy anyone And unlucky my first problem is that I am not good in English as well as in grammar so, If u don’t mind any u tell me any idea how to start my dream work ???? And Yaa one more thing I want to tell my dream company also which I want to work with and the name is (rolling stone) so u think in future there is any chance to get or touch my dream???

Thanks Ressa, I appreciate your thoughts! A profile is one type of feature article, so I meant what I originally wrote 🙂

There sure are a lot of choices for magazine articles…but my favorite is still blogging. I love the freedom and immediacy of writing blog posts, without having to worry about pitching article ideas to editors. But, blogging doesn’t offer as much exposure as writing for magazines does. Unless of course you write for the HuffPost!

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Write a Magazine Article

Last Updated: October 11, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Gerald Posner . Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 931,313 times.

Magazine articles can be a big boost for seasoned freelance writers or writers who are trying to jump-start their writing careers. In fact, there are no clear qualifications required for writing magazine articles except for a strong writing voice, a passion for research, and the ability to target your article pitches to the right publications. Though it may seem like magazines may be fading in the digital age, national magazines continue to thrive and can pay their writers $1 a word. [1] X Research source To write a good magazine article, you should focus on generating strong article ideas and crafting and revising the article with high attention to detail.

Generating Article Ideas

- Check if the bylines match the names on the masthead. If the names on the bylines do not match the masthead names, this may be an indication that the publication hires freelance writers to contribute to its issues.

- Look for the names and contact information of editors for specific areas. If you’re interested in writing about pop culture, identify the name and contact information of the arts editor. If you’re more interested in writing about current events, look for the name and contact information of the managing editor or the features editor. You should avoid contacting the executive editor or the editor-in-chief as they are too high up the chain and you will likely not interact with them as a freelance writer.

- Note recent topics or issues covered in the publication and the angle or spin on the topics. Does the publication seem to go for more controversial takes on a topic or a more objective approach? Does the publication seem open to experimentation in form and content or are they more traditional?

- Look at the headlines used by the publication and how the articles begin. Note if the headlines are shocking or vague. Check if the articles start with a quote, a statistic, or an anecdote. This will give you a good sense of the writing style that gets published in that particular publication.

- Note the types of sources quoted in the articles. Are they academic or more laymen? Are there many sources quoted, or many different types of sources quoted?

- Pay attention to how writers wrap up their articles in the publication. Do they end on a poignant quote? An interesting image? Or do they have a bold, concluding thought?

- These inspiring conversations do not need to be about global problems or a large issue. Having conversations with your neighbors, your friends, and your peers can allow you to discuss local topics that could then turn into an article idea for a local magazine.

- You should also look through your local newspaper for human interest stories that may have national relevance. You could then take the local story and pitch it to a magazine. You may come across a local story that feels incomplete or full of unanswered questions. This could then act as a story idea for a magazine article.

- You can also set your Google alerts to notify you if keywords on topics of interest appear online. If you have Twitter or Instagram, you can use the hashtag option to search trending topics or issues that you can turn into article ideas.

- For example, rather than write about the psychological problems of social media on teenagers, which has been done many times in many different magazines, perhaps you can focus on a demographic that is not often discussed about social media: seniors and the elderly. This will give you a fresh approach to the topic and ensure your article is not just regurgitating a familiar angle.

Crafting the Article

- Look for content written by experts in the field that relates to your article idea. If you are doing a magazine article on dying bee populations in California, for example, you should try to read texts written by at least two bee experts and/or a beekeeper who studies bee populations in California.

- You should ensure any texts you use as part of your research are credible and accurate. Be wary of websites online that contain lots of advertisements or those that are not affiliated with a professionally recognized association or field of study. Make sure you check if any of the claims made by an author have been disputed by other experts in the field or have been challenged by other experts. Try to present a well-rounded approach to your research so you do not appear biased or slanted in your research.

- You can also do an online search for individuals who may serve as good expert sources based in your area. If you need a legal source, you may ask other freelance writers who they use or ask for a contact at a police station or in the legal system.

- Prepare a list of questions before the interview. Research the source’s background and level of expertise. Be specific in your questions, as interviewees usually like to see that you have done previous research and are aware of the source’s background.

- Ask open-ended questions, avoid yes or no questions. For example, rather than asking, "Did you witness the test trials of this drug?" You can present an open-ended question, "What can you tell me about the test trials of this drug?" Be an active listener and try to minimize the amount of talking you do during the interview. The interview should be about the subject, not about you.

- Make sure you end the interview with the question: “Is there anything I haven’t asked you about this topic that I should know about?” You can also ask for referrals to other sources by asking, “Who disagrees with you on your stance on this issue?” and “Who else should I talk to about this issue?”

- Don’t be afraid to contact the source with follow-up questions as your research continues. As well, if you have any controversial or possibly offensive questions to ask the subject, save them for last.

- The best way to transcribe your interviews is to sit down with headphones plugged into your tape recorder and set aside a few hours to type out the interviews. There is no short and quick way to transcribe unless you decide to use a transcription service, which will charge you a fee for transcribing your interviews.

- Your outline should include the main point or angle of the article in the introduction, followed by supporting points in the article body, and a restatement or further development of your main point or angle in your conclusion section.

- The structure of your article will depend on the type of article you are writing. If you are writing an article on an interview with a noteworthy individual, your outline may be more straightforward and begin with the start of the interview and move to the end of the interview. But if you are writing an investigative report, you may start with the most relevant statements or statements that relate to recent news and work backward to the least relevant or more big picture statements. [10] X Research source

- Keep in mind the word count of the article, as specified by your editor. You should keep the first draft within the word count or just above the word count so you do not lose track of your main point. Most editors will be clear about the required word count of the article and will expect you not to go over the word count, for example, 500 words for smaller articles and 2,000-3,000 words for a feature article. Most magazines prefer short and sweet over long and overly detailed, with a maximum of 12 pages, including graphics and images. [11] X Research source

- You should also decide if you are going to include images or graphics in the article and where these graphics are going to come from. You may contribute your own photography or the publication may provide a photographer. If you are using graphics, you may need to have a graphic designer re create existing graphics or get permission to use the existing graphics.

- Use an interesting or surprising example: This could be a personal experience that relates to the article topic or a key moment in an interview with a source that relates to the article topic. For example, you may start an article on beekeeping in California by using a discussion you had with a source: "Darryl Bernhardt never thought he would end up becoming the foremost expert on beekeeping in California."

- Try a provocative quotation: This could be from a source from your research that raises interesting questions or introduces your angle on the topic. For example, you may quote a source who has a surprising stance on bee populations: "'Bees are more confused than ever,' Darryl Bernhart, the foremost expert in bees in California, tells me."

- Use a vivid anecdote: An anecdote is a short story that carries moral or symbolic weight. Think of an anecdote that might be a poetic or powerful way to open your article. For example, you may relate a short story about coming across abandoned bee hives in California with one of your sources, an expert in bee populations in California.

- Come up with a thought provoking question: Think of a question that will get your reader thinking and engaged in your topic, or that may surprise them. For example, for an article on beekeeping you may start with the question: "What if all the bees in California disappeared one day?"

- You want to avoid leaning too much on quotations to write the article for you. A good rule of thumb is to expand on a quotation once you use it and only use quotations when they feel necessary and impactful. The quotations should support the main angle of your article and back up any claims being made in the article.

- You may want to lean on a strong quote from a source that feels like it points to future developments relating to the topic or the ongoing nature of the topic. Ending the article on a quote may also give the article more credibility, as you are allowing your sources to provide context for the reader.

Revising the Article

- Having a conversation about the article with your editor can offer you a set of professional eyes who can make sure the article fits within the writing style of the publication and reaches its best possible draft. You should be open to editor feedback and work with your editor to improve the draft of the article.

- You should also get a copy of the publication’s style sheet or contributors guidelines and make sure the article follows these rules and guidelines. Your article should adhere to these guidelines to ensure it is ready for publication by your deadline.

- Most publications accept electronic submissions of articles. Talk with your editor to determine the best way to submit the revised article.

Sample Articles

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

Expert Interview

Thanks for reading our article! If you'd like to learn more about writing an article, check out our in-depth interview with Gerald Posner .

- ↑ http://grammar.yourdictionary.com/grammar-rules-and-tips/tips-on-writing-a-good-feature-for-magazines.html

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/writing-articles/20-ways-to-generate-article-ideas-in-20-minutes-or-less

- ↑ http://www.writerswrite.com/journal/jun03/eight-tips-for-getting-published-in-magazines-6036

- ↑ http://www.thepenmagazine.net/20-steps-to-write-a-good-article/

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R5f2VV58pw

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-nonfiction/how-many-different-kinds-of-articles-are-there

- ↑ http://libguides.unf.edu/c.php?g=177086&p=1163719

About This Article

To write a magazine article, start by researching your topic and interviewing experts in the field. Next, create an outline of the main points you want to cover so you don’t go off topic. Then, start the article with a hook that will grab the reader’s attention and keep them reading. As you write, incorporate quotes from your research, but be careful to stick to your editor’s word count, such as 500 words for a small article or 2,000 words for a feature. Finally, conclude with a statement that expands on your topic, but leaves the reader wanting to learn more. For tips on how to smoothly navigate the revision process with an editor, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Smriti Chauhan

Sep 20, 2016

Did this article help you?

Jasskaran Jolly

Sep 1, 2016

Emily Jensen

Apr 5, 2016

May 5, 2016

Ravi Sharma

Dec 25, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

- Online Flipbook

- Online Catalog

- Online Magazine

- Online Brochure

- Digital Booklet

- Business Proposal

- Real Estate Flyer

- Multimedia Presentation

- Ebook Online

- Online Photo Album

- Online Portfolio

- Company Newsletter

- Lead Generation

- Document Tracking

- PDF Statistics

- Virtual Bookshelf

- Flipbook App

Knowledge Base > Magazines > How to Write a Magazine Article? 12 Golden Rules

How to Write a Magazine Article? 12 Golden Rules

Although the number of magazines is shrinking in the digital age, many magazines have moved online. Many magazines created by online magazine maker are still popular, and authors enjoy fame and respect. That’s why, for many freelance writers, writing articles in magazines is often a career goal – because the pay can be ten times more per word than writing articles or texts for the local newspaper.

Writing magazine articles requires a different skill set than writing blog posts, screenplays, or advertisements. What’s more, as a magazine writer, more than in any other industry, you need to specialize to succeed. You write articles about history differently, sports differently, and sports history in a different way still.

A talent for writing, a love of meticulous research, and flexibility in creating texts are vital skills you need to master. Therefore, many people are interested in creating and publishing their own magazine need to master this specific style and learn how to write a magazine article.

What is a magazine?

A magazine is a publication that is a collection of articles that appears regularly. The magazine articles can be about any topic, as well as topics that interest a specific group, such as sports fans, music fans, or board game enthusiasts.

A magazine can be published weekly, monthly, bimonthly, or only a few times a year. Most magazines are published once a week or once a month. Most magazine articles do not have a list of sources and are written by regular magazine editors and writers, rarely freelance writers.

Most magazine articles are easy to read and don’t take too long to read. They are often illustrated with photos or other images, and are written with simple but remarkable fonts . Today, magazines are increasingly being replaced by websites, but there are still many magazines on various topics.

What is a magazine article?

A magazine article is a specific text that can be found in a magazine or newspaper. It can be a report, a profile of an important person, an opinion piece, a discussion of a topic or a personal essay. Depending on the topic, a magazine article is usually 1,000 to 5,000 words long.

The magazine usually employs a group of editors who come up with a theme for each issue and relevant article ideas. This way, all the articles and features in the issue will have something in common. A sports magazine might talk about the start of a new season, a political magazine about an upcoming election, and a Valentine’s Day issue might be about romance.

How the format of a magazine article differs from that of a newspaper or other articles? In a newspaper that comes out every day, put the most important parts of the story first. Newspaper articles are usually read once and aren’t supposed to influence anyone. It has to be news, something you want to read.

On the other hand, a good magazine article should often start with a mystery, a question, or a situation that makes the reader want to read on. Daily newspaper articles should be unbiased descriptions of what happened, while magazine articles, often subjective, can cover a particular topic from a certain angle. To learn how to write a magazine article, you need to know what the magazine is about and how to appeal to its readers.

Create a digital magazine with Publuu

Today, more and more people are creating magazines in purely digital form. Publuu converts PDF files into interactive digital magazines that you can easily view and share online. With support for HTML5 and vector fonts, your articles will look beautiful on any device, without the need to download additional apps.

Publuu makes your magazine article look and sound like the printed versions. Converting a regular PDF file into a flipping e-magazine using this service is extremely easy and fast.

Publuu’s online magazine example

View more online magazine examples

MAKE YOUR OWN

With Publuu, your readers can flip through the pages just as they would with a real paper magazine, but that’s not all. Rich multimedia capabilities, analytics, and easy access make many people publish content for free on Publuu.

Your audience, and you, can embed your magazines in websites or emails, or share them on social media platforms. It only takes one click to go to your magazine and start reading interesting articles.

Types and examples of magazine articles

Magazine editors categorize articles by type and often mention them in publication’s submission guidelines, so knowing these types by name will help you communicate with the editor. These are: First Person Article, Opinion Piece, Information or Service Piece, Personality Profile, and Think Piece. Many news articles, how-to articles, and reviews can also be found in magazines, but they are slightly different, and many of these have moved online, to digital magazines . Articles can also feature essays or humor pieces.

First Person Article

First-person magazine articles are written in the first person because they are based on personal experience. Depending on their length and newsworthiness, they can be sold as feature articles or essays. They are frequently personal accounts, especially interesting if they are written by a well-known magazine writer or celebrity. Typically, the purpose of such an article is stated in the first line or paragraph to hook the magazine’s target audience, such as “I voted for this politician, and now I regret my life choices.” When you write a magazine article like this one, you should present an unpopular or overlooked point of view from a fresh perspective.

Opinion Piece

This kind of magazine writing piece or opinion essay is less personal than the First-Person Article, but it still requires a narrow focus on a specific topic. The reader’s main question is, “Why are you qualified to render an opinion?” Everyone has an opinion, but why should anyone read yours?

If you’re an expert on this subject, let the reader know right away. Don’t criticize music trends if you’re not a musician! Demonstrate your knowledge, and support your opinion with up-to-date information and credentials.

Information/Service Piece

An informational or service piece expands the reader’s understanding of a particular subject. This can be a guide, a list of important issues. You can either be the expert or interview one. These are extremely pertinent to a specific industry. In a sports magazine article, you can explain a complete history of a sports team and its roster for the upcoming season.

You can expect some in-depth knowledge if the article title contains the phrases like Myths about or Secrets of. Explain everything you know: magazine journalism is different than being a freelance writer in that you should have some industry knowledge already.

Personality profile

This type of magazine article can present a silhouette of an important or relevant person – a politician, a political activist, a sports legend… If you’re writing for a video game magazine you can showcase a famous game designer or even an entire article can be about a game character like Lara Croft or Guybrush Threepwood, if the fictional character is detailed enough! Explain why readers will find this person interesting or noteworthy.

Think Piece

Written in an investigative tone, the think piece frequently shows the downside or less popular ideas of a popular industry aspect. This magazine article could also explain why something is popular or why a political party lost elections. A think piece is more in-depth than most feature articles and necessitates credibility. Confirm your thesis by interviewing analysts and experts. This type of article can be also found in zines , self-published magazines in small circulation, which often focus on niche hobbies, counterculture groups, or subcultures. If you would like to expend your knowledge about interviewing, make sure to check our guide on how to write an interview article .

How to start a magazine article?

Most creative writing professionals would agree that the best way to start writing a magazine article is with a strong opening sentence. A feature article must draw the attention of your target audience, and grab them from the go.

You can start by asking the reader a question which you will answer in the text of the article – for instance “Did you know that most users of Windows never use 80% of their functions – and that’s a good thing?”. In the content of your magazine articles you will be able to answer this question.

Another example of a good magazine article beginning is storytelling – human brains are fascinated by stories. Starting your example with “20 years ago no one in the industry knew what a genitine was, but now their inventor is one of the most influential people” can draw attention and spike up curiosity.

A great example is also a shocking quote – a compelling idea that goes against the grain is sure to capture the reader’s attention.

Most creative magazine article ideas

Even the most experienced journalists can often be looking for ideas for great articles. How to write a magazine article if you don’t have the slightest idea? Here are some of our suggestions:

Take a look at your specialty. If you’re a freelance writer, it’s a good idea to write about what you know. Delve into a topic thoroughly, and you’ll eventually find your niche and you might move from freelance writing jobs to magazine writing! Why? Having a writing specialty will make magazine editors think of you when story ideas in that genre come up.

Check out what’s trending. When browsing popular stories on social networks, many freelancers choose to write about current events. Lists of popular articles can help you understand what to focus your efforts on. Keep in mind that an article for national magazines needs to be well researched, and what’s trending now may change before the magazine finally comes out.

Reach out to the classics. Nostalgia always sells well. You can go back to books or movies that people remember from their youth or, for example, summarize the last year. Lists and numbers always look good!

12 rules on how to write great magazine articles

1. Write what you know about

If your articles are really fascinating and you know what you are writing about, you have a better chance of getting published, whether in a local newspaper or in a major magazine. Writing requires researching your chosen issue thoroughly. Identify perspectives that have not been explored before – describe something from the perspective of a woman, a minority, or a worker.

2. Research how you should write

Check the writing style requirements or guidelines of the magazines to which you want to submit your work. Each magazine has its own set of guidelines on what topics, manner and tone to use. Check out Strunk and White Elements of Style for tips on writing styles, as this is what many magazines draw from.

3. Remember to be flexible

One of the most valuable writing talents a journalist can possess is flexibility. You may find that you discover completely new facts while writing a magazine article and completely change your approach. Maybe you’ll change your mind 180 degrees and instead of attacking someone, you’ll defend them – anything to attract attention.

4. Make connections and meet people

Networking is important in any business, especially for freelance writers who want to make a jump to magazine writing. Editors regularly quit one magazine to work for another. Therefore, remember to know the people first and foremost than the magazine they work for.

5. Prepare a query letter

A query letter tells the editors why your magazine article is important, whether you think someone will want to read it and why you feel obligated to write it. Add to it a text sample and some information about yourself as a writer. Even a local magazine might not be aware of who you are, after all.

6. Prepare an outline

Always before writing a text have an outline that you can use when composing your articles. It must contain the important ideas, the content of the article body and the summary, the points you will include in it. You will find that it is easier to fill such a framework with your own content.

7. Meet the experts

You need to know pundits in your industry. There are several methods of locating experts, from networking to calling organizations or agencies in your field of interest. If you want to meet a police officer, call the police station and ask if someone could talk to a journalist – many people are tempted if you promise them a feature article.

8. Talk to experts

Once you get a contact for an expert, do your best to make the expert look as good as possible. The more prominent the expert, the better your text. Make a list of questions in advance and compare it with the outline to make sure you don’t forget anything. Remember to accurately describe your expert’s achievements and personal data.

9. Create a memorable title

This step can occur at any point in the process of writing an article for a magazine. Sometimes the whole article starts with a good title! However, there is nothing wrong with waiting until the article is finished before coming up with a title. The most important thing is that the title is catchy – editors-in-chief love that!

10. To write, you have to read

You never know where you will come across an inspiring text. It’s your duty as a good writer to read everything that falls into your hands, whether it’s articles on the front pages of major publications or small blog posts. Learn about the various issues that may be useful to your magazine writing skills.

11. Add a strong ending

End with a strong concluding remark that informs or elaborates on the theme of your piece. The last paragraph should make the reader satisfied, but also curious about the future progress of the issue. He must wonder “what’s next?” and answer the important questions himself.

12. Don’t give up

Writers are rejected hundreds of times, especially when they are initially learning how to create articles for magazines. However, even a seasoned freelance writer and professional journalist can get rejected. The most successful authors simply keep writing – being rejected is part of magazine writing. Freelance writing is a good school of writing career – including coping with rejection.

Now you know how to write a magazine article that will be engaging and interesting. Despite the digitalization of the market, writing magazine articles still offers many possibilities to a freelance writer or a seasoned professional. The market of press and magazines is evolving fast, but the basic principles of journalistic integrity stay the same!

You may be also interested in:

How To Publish Digital Magazine? How to Make a Magazine Cover With a Template? 5 Reasons to Start Using a Magazine Maker

Jakub Osiejewski is an experienced freelance writer and editor. He has written for various publications, including magazines, newspapers and websites. He is also a skilled layout graphic designer and knows exactly how to create visually appealing and informative PDFs and flipbooks!

Recent posts

- Flipbook Expert (13)

- PDF Expert (20)

- Catalogs (33)

- Brochures (44)

- Magazines (29)

- Real Estates (17)

- Portfolios (15)

- Booklets (13)

- Presentations (19)

- Education (8)

- Newsletters (13)

- Photo Albums (7)

- Ebooks (28)

- Business Proposals (16)

- Marketing Tips (53)

Popular articles

Convert your PDF to flipbook today!

Go beyond boring PDF and create digital flipbook for free. Register with Publuu for free today and check out all the smart options we prepared for you!

This site uses cookies. Learn more about the purpose of their use and changing cookie settings in your browser. By using this website you agree to the use of cookies in accordance with your current browser settings.

Search form

A magazine article.

Look at the magazine article and do the exercises to improve your writing skills.

Instructions

Do the preparation exercise first. Then read the text and do the other exercises.

Preparation

Can you get five correct answers in a row? Press reset to try again.

Check your understanding: multiple choice

Check your writing: word 2 word - questions, check your writing: gap fill - opinion adverbs, worksheets and downloads.

How serious a problem is bullying where you live? What can be done to stop bullying in schools?

Sign up to our newsletter for LearnEnglish Teens

We will process your data to send you our newsletter and updates based on your consent. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link at the bottom of every email. Read our privacy policy for more information.

- Share full article

Why Did This Guy Put a Song About Me on Spotify?

The answer involves a remarkable — and lucrative, and ridiculous — scheme to game the way we find music today.

Matt Farley has released thousands of songs with the goal of producing a result to match nearly anything anybody could think to search for. Credit... Chris Buck for The New York Times

Supported by

By Brett Martin

Brett Martin is a contributing writer for the magazine. For this story, he traveled to Massachusetts to meet the writer of the song “Brett Martin, You a Nice Man, Yes.”

- Published March 31, 2024 Updated April 1, 2024

I don’t want to make this all about me, but have you heard the song “Brett Martin, You a Nice Man, Yes” ?

I guess probably not. On Spotify, “Brett Martin, You a Nice Man, Yes” has not yet accumulated enough streams to even register a tally, despite an excessive number of plays in at least one household that I can personally confirm. Even I, the titular Nice Man, didn’t hear the 1 minute 14 second song until last summer, a full 11 years after it was uploaded by an artist credited as Papa Razzi and the Photogs. I like to think this is because of a heroic lack of vanity, though it may just be evidence of very poor search skills.

Listen to this article, read by Eric Jason Martin

Open this article in the New York Times Audio app on iOS.

When I did stumble on “Brett Martin, You a Nice Man, Yes,” I naturally assumed it was about a different, more famous Brett Martin: perhaps Brett Martin, the left-handed reliever who until recently played for the Texas Rangers; or Brett Martin, the legendary Australian squash player; or even Clara Brett Martin, the Canadian who in 1897 became the British Empire’s first female lawyer. Only when the singer began referencing details of stories that I made for public radio’s “This American Life” almost 20 years ago did I realize it actually was about me. The song ended, “I really like you/Will you be my friend?/Will you call me on the phone?” Then it gave a phone number, with a New Hampshire area code.

So, I called.

It’s possible that I dialed with outsize expectations. The author of this song, whoever he was, had been waiting 11 long years as his message in a bottle bobbed on the digital seas. Now, at long last, here I was! I spent serious time thinking about how to open the conversation, settling on what I imagined was something simple but iconic, on the order of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.” After one ring, a male voice answered.

I said: “This is Brett Martin. I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to call.”

The man had no idea who I was.

“You have to understand,” he said, apologetically. “I’ve written over 24,000 songs. I wrote 50 songs yesterday.”

And thus was I ushered into the strange universe of Matt Farley.

Farley is 45 and lives with his wife, two sons and a cockapoo named Pippi in Danvers, Mass., on the North Shore. For the past 20 years, he has been releasing album after album of songs with the object of producing a result to match nearly anything anybody could think to search for. These include hundreds of songs name-checking celebrities from the very famous to the much less so. He doesn’t give out his phone number in all of them, but he does spread it around enough that he gets several calls or texts a week. Perhaps sensing my deflation, he assured me that very few came from the actual subject of a song. He told me the director Dennis Dugan (of “Dennis Dugan, I Like Your Movies Very A Lot,” part of an 83-song album about movie directors) called once, but he didn’t realize who it was until too late, and the conversation was awkward.