Literature Circles

- Posted November 12, 2021

- By Emily Boudreau

- Language and Literacy Development

- Teachers and Teaching

When you find yourself reading a good book, whether you’re on the edge of your seat wondering what a character will do next or amazed by the poetry of a descriptive passage, you probably want to share what you’ve read with someone — not write a book report or build a diorama, as students are often asked to do.

“There’s an excitement around sharing words,” says Harvard Graduate School of Education senior lecturer and Jeanne Chall Reading Lab director Pamela Mason , whose work and research focuses on developing culturally responsive and effective literacy and reading instructional practices. “Children have a right to those experiences, and they want those types of experiences. That’s what makes learning fun and engages them in school.”

So how can educators encourage natural discussion and enthusiasm for books in the classroom while also ensuring students understand what they’re reading and continue to grow as readers?

Why Literature Circles?

Literature circles — a small group of students that gathers to discuss a book, much like a book club — are not a new idea , and in fact, remain quite popular because they are incredibly effective . Indeed, many studies of developing reading comprehension, including those by Harvard Graduate School of Education professor Catherine Snow , have emphasized the positive impact of having kids talk about what they read.

Talking about reading also helps build a classroom culture around books. “It’s motivating,” says Mason. “We’ve found from the research that, regardless of what you read, the more you read, the better you get. And the better you get, the more you like it. The more you like it, you feel competent at it, and it’s this virtuous cycle . [Reading becomes] something I do, that my friends do.”

“There’s an excitement around sharing words. Children have a right to those experiences, and they want those types of experiences. That’s what makes learning fun and engages them in school.”

Those conversations allow readers to hone their critical thinking skills. They might think about the decisions a character makes or whether they agree with something a classmate has said as they make connections between the book and themselves, other books they’ve read, or something they’ve seen on the news or heard about in their communities.

Using Literature Circles Successfully

Mason has a few ideas to make them more successful and to help educators overcome common hiccups, like differentiating appropriately and avoiding overly teacher-led conversations, when implementing literature circles.

THE PROBLEM:

Balancing reading requirements with student choice. Students devour the latest Percy Jackson book but are less enthusiastic about picking up their assigned reading from The Odyssey.

From required summer reading lists to being told a book is too difficult or too easy, school-age children aren’t always given a choice when selecting reading material. Yet according to Mason, choice is essential. It’s part of what makes reading fun for adults and that needs to be extended to children as well. With so many choices, including graphic novels and e-books, teachers can have children reading the same book or following the same storyline in different media.

It’s also important to think about whether the text students are reading reflects their backgrounds and interests. “Think about the texts you’re offering — are they varied in terms of content, representation of characters, and settings that represent the learners in your classroom? Are they multilingual?” says Mason.

THE PROBLEM:

Students have a wide variety of strengths and weaknesses as readers, yet you want to avoid stigmatizing students based on their assessed reading level.

Mix up the reading groups so they aren’t always based on assessed reading levels. It can be important to have students read texts that are accessible and to do so alongside readers who can also access those books. However, there are other factors to take into consideration. “Teachers can give students a test and a score — but that score doesn’t measure motivation, doesn’t measure background knowledge, or the type of text a learner might be able to access because of those knowledges,” says Mason. Nonfiction texts can also be used in literature circles — consider mixing up the groups and allowing students to choose their literature circle based on a shared topic of interest.

Mason also notes that readers don’t always need to be challenged. Given the right kind of framing or thought-provoking questions, a simple text can still hone a reader’s skills . For example, asking high schoolers to revisit some of their favorite picture books from childhood and to think critically about how they absorbed that message can be powerful. For example, what does Where the Wild Things Are say about anger?

“We’ve found from the research that, regardless of what you read, the more you read, the better you get. And the better you get, the more you like it. The more you like it, you feel competent at it, and it’s this virtuous cycle.”

THE PROBLEM

Students look to the teacher after answering questions, rather than turning to each other.

Evaluate how you model discussions in your classroom. Do the students respond to each other? Or does one student respond and then you speak to the next student? Try calling students in to the discussion by asking if they have something to add. Also, ask them what they think of what another student has said. Taking turns, stepping back and allowing someone else to talk, being curious and not judgmental, and perspective-taking should be part of community agreements in the classroom and modeled in all subject areas.

Students struggle to stay on-task in small groups or give one-word answers to discussion questions. Maybe some students aren’t as involved in the conversation as others.

Typically, literature circles include assigning roles to students. While these roles can become stagnant and rigid in some circumstances, they can be a great way to add structure and coax reluctant participants into contributing. Some examples of roles include a student who is making connections, finding a passage that strikes them, or illustrating a scene. Mason recommends, though, that students rotate roles so all learners can gain experience contributing in a different way and, once the discussion starts to flow regularly, phasing out the roles.

Tips from a Teacher

Robin Loewald, a 2019 master’s graduate from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, works as a high school English teacher in Melrose, Massachusetts. Here, she provides a few key takeaways on how she’s used literature circles.

- “My biggest role as an educator is to create a space and structure for a discussion to be successful,” says Loewald. To do that, she dedicates time early in the year to establish expectations and set the tone . “We play a lot of games, things like rock, paper, scissor tournaments, so kids get to know each other and are comfortable using each other’s names. This makes them more comfortable talking about things that are important or serious later on.”

- She’s also found that literature circles can be a powerful way to connect students , even during remote learning. Letting students choose the book is also important and can promote engagement. “Even in remote spaces, when they’re talking about a book they care about, you can feel the investment, emotion, and pride in their conversations.”

- Use the opportunity to tackle difficult subjects. Loewald lead a voluntary book club over the summer because students expressed a desire to talk about race. “It helps students feel like they’re able to engage in a conversation that can be challenging. [The book] gives them a reference point and a shared vocabulary to talk about really important things.”

Additional Resources

- Read this UK story on how to bring controversial books into the classroom.

- An Ed. magazine story on how to teach reading.

- Listen to an EdCast with Professor James Kim, Beyond the Literacy Debate.

- Read an essay by Loewald in Ed. magazine on teaching virtually.

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Building Background Knowledge in Science Improves Reading Comprehension

Help Teens Connect to Fiction

Navigating Literacy Challenges, Fostering a Love of Reading

With ongoing debates around the best ways to teach reading, what makes for truly effective literacy instruction?

Advertisement

Engaging Students in Literature Circles: Vocational English Reading Programs

- Regular Article

- Published: 14 December 2015

- Volume 25 , pages 347–359, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Handoyo Puji Widodo 1

1874 Accesses

13 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article reports the findings of ethnographic classroom research on the deployment of literature circles in English reading classes in the vocational secondary education sector in Indonesia. Grounded in micro-interactional, thematic, and discourse analyses, empirical findings showed that the students engaged actively in text selection, role assignment, and text meaning making through sharing-and-discussion sessions. Empirical data also revealed that they could learn a wide array of lexico-grammar through discussing chosen texts with others. This group discussion activity also paves the way for sharing and discussing both content knowledge (vocational subjects) and genre and lexico-grammatical features. This suggests that literature circles could promote students’ content knowledge and language learning enrichment. Through role scaffolding by teachers and peer support, students could not only explore varied features of the language—e.g., how lexico-grammar was used in context through texts but also enrich their content knowledge. This empirical evidence supports the use of the literature circles in intensive reading programs in order to engage students in collaborative learning and to build a learning community in which teachers play a pivotal role as a guide throughout the literature circle process.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Educational Affordances and Challenges of ChatGPT: State of the Field

Helen Crompton & Diane Burke

Transition to school: children’s perspectives of the literacy experiences on offer as they move from pre-school to the first year of formal schooling

Lynette Patricia Cronin, Lisa Kervin & Jessica Mantei

Teaching creative writing in primary schools: a systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity

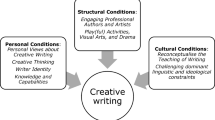

Georgina Barton, Maryam Khosronejad, … Debra Myhill

Anderson, K. T. (2009). Applying positioning theory to the analysis of classroom interactions: Mediating micro-identities, macro-kinds, and ideologies of knowing. Linguistics and Education, 20 , 291–310.

Article Google Scholar

Brabham, E. G., & Villaume, S. K. (2000). Continuing conversations about literature circles. The Reading Teacher, 54 , 278–280.

Google Scholar

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 , 77–101.

Braun, V., & Wilkinson, S. (2003). Liability or asset? Women talk about the vagina. Psychology of Women Section Review, 5 , 28–42.

Bruce, C. D., Flynn, T., & Stagg-Peterson, S. (2011). Examining what we mean by collaboration in collaborative action research: A cross-case analysis. Educational Action Research, 19 , 433–452.

Cameron, S., Murray, M., Hull, K., & Cameron, J. (2012). Engaging fluent readers using literature circles. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years, 20 (1), 1–8.

Canals, A. (2011). Will increased participation, on the part of each student, in literature circles equate to higher achievement in comprehension scores in an eighth grade English class? (Caldwell College). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 58. http://search.proquest.com/docview/868707657?accountid=8203 .

Daniels, H. (2002). Expository text in literature circles. Voices from the Middle, 9 (4), 7–14.

Daniels, H. (2006). What’s the next big thing with literature circles? Voices from the Middle, 13 (4), 10–15.

DuFon, M. A. (2002). Video recording in ethnographic SLA research: Some issues of validity in data collection. Language Learning and Technology, 6 (1), 40–59.

Duncan, S. (2012). Reading circles, novels and adult reading development . London: Continuum.

Feldman, G. (2011). If ethnographer is more than participant-observation, then relations are more than connections: The case for nonlocal ethnography in a world of apparatuses. Anthropological Theory, 11 , 375–395.

Fetterman, D. M. (2010). Ethnography: Step by step (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gordon, C. (2013). Beyond the observer’s paradox: The audio-recorder as a resource for the display of identity. Qualitative Research, 13 , 299–317.

Hedgcock, J. S., & Ferris, D. R. (2009). Teaching readers of English: Students, texts, and contexts . New York: Routledge.

Holloway, S. M. (2011). Literature circles: Encouraging critical literacy, dual-language reading, and multi-modal approaches. English Quarterly, 42 (3–4), 21–35.

Kern, A. L., Roehrig, G., & Wattam, D. K. (2012). Inside a beginning immigrant science teacher’s classroom: An ethnographic study. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 18 , 469–481.

Labaree, R. V. (2002). The risk of ‘going observationalist’: Negotiating the hidden dilemmas of being an insider participant observer. Qualitative Research, 2 , 97–122.

Leonardi, V. (2010). The role of pedagogical translation in second language acquisition: From theory to practice . Bern: Peter Langa AG.

Littlewood, W., & Yu, B. (2011). First language and target language in the foreign language classroom. Language Teaching, 44 (1), 64–77.

Macalister, J. (2011). Today’s teaching, tomorrow’s text: Exploring the teaching of reading. ELT Journal, 65 , 161–169.

Mark, P. L. (2007). Building a community of EFL readers: Setting up literature circles in a Japanese university. In K. Bradford-Watts (Ed.), JALT 2006 conference proceedings . Tokyo: JALT. http://jalt-publications.org/archive/proceedings/2006/E038.pdf .

Martínez-Roldán, C. M., & López-Robertson, J. M. (2000). Initiating literature circles in a first-grade bilingual classroom. The Reading Teacher, 53 , 270–281.

McElvain, C. M. (2010). Transactional literature circles and the reading comprehension of English learners in the mainstream classroom. Journal of Research in Reading, 33 , 178–205.

Mickan, P. (2013). Language curriculum design and socialisation . Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Nation, P. (2009). Reading faster. International Journal of English Studies, 9 (2), 131–144.

Nolasco, J. L. (2009). Effects of literature circles on the comprehension of reading expository texts (Caldwell College). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 51. http://search.proquest.com/docview/305172713?accountid=8203 .

Rowland, L., & Barrs, K. (2013). Working with textbooks: Reconceptualising student and teacher roles in the classroom. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 7 , 57–71.

Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2012). Literature circles in ELT. ELT Journal, 66 , 214–223.

Vardell, S. M., Hadaway, N. L., & Young, T. A. (2006). Matching books and readers: Selecting literature for english learners. The Reading Teacher, 59 , 734–741.

Wang, X. (2013). The construction of researcher–researched relationships in school ethnography: Doing research, participating in the field and reflecting on ethical dilemmas. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26 , 763–779.

Widodo, H. P. (2015a). Designing and implementing task-based Vocational English (VE) materials: Text, language, task, and context. In H. Reinders & M. Thomas (Eds.), Contemporary task-based language learning and teaching (TBLT) in Asia: Challenges, opportunities and future directions (pp. 291–312). London: Bloomsbury.

Widodo, H. P. (2015b). The development of Vocational English materials from a social semiotic perspective: Participatory action research (Unpublished PhD thesis) . Australia: The University of Adelaide.

Yan, C., & He, C. (2012). Bridging the implementation gap: An ethnographic study of English teachers’ implementation of the curriculum reform in China. Ethnography and Education, 7 (1), 1–19.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This Research Project was fully funded by the University of Adelaide, Australia. I am grateful to the school and to the participants who volunteered to participate in the Research Project. My sincere thanks also go to my PhD supervisors, Dr. Peter Mickan, and Dr. John Walsh for their continued personal and professional support. I wish to thank two anonymous reviewers and Dr. Icy Lee for their insightful feedback on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Politeknik Negeri Jember, Perumnas Kodim 0824 Gang 1 Nomor 8 Jubung, Jember, Jawa Timur, Indonesia

Handoyo Puji Widodo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Handoyo Puji Widodo .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Widodo, H.P. Engaging Students in Literature Circles: Vocational English Reading Programs. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 25 , 347–359 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0269-7

Download citation

Published : 14 December 2015

Issue Date : April 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0269-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Dialogic reading

- Ethnographic classroom research

- Literature circles

- Vocational English

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Literature Circles: Getting Started

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

This lesson provides a basic introduction to literature circles, a collaborative and student-centered reading strategy. Students begin by selecting a book together then are introduced to the four jobs in the Literature Circles: Discussion Director, Literary Luminary, Vocabulary Enricher, and Checker. The teacher and student volunteers model the task for each of the four roles, and then students practice the strategies. The process demonstrates the different roles and allows students to practice the techniques before they are responsible for completing the tasks on their own. After this introduction, students are ready to use the strategy independently, rotating the roles through four-person groups as they read the books they have chosen. The lesson can then be followed with a more extensive literature circle project.

Featured Resources

Self-Reflection: Taking Part in a Group Interactive : Using this online tool, students describe their interactions during a group activity, as well as ways in which they can improve. Students can add rows and columns to the chart and print their finished work.

From Theory to Practice

Literature circles are a strong classroom strategy because of the way that they couple collaborative learning with student-centered inquiry. As they conclude their description of the use of literature circles in a bilingual classroom, Peralta-Nash and Dutch explain the ways that the strategy helped students become stronger readers:

Students learned to take responsibility for their own learning, and this was reflected in how effectively they made choices and took ownership of literature circle groups. They took charge of their own discussions, held each other accountable for how much or how little reading to do, and for the preparation for each session. The positive peer pressure that the members of each group placed on each other contributed to each student's accountability to the rest of the group. (36)

When students engage with texts and one another in these ways, they take control of their literacy in positive and rewarding ways.

Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 2. Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 9. Students develop an understanding of and respect for diversity in language use, patterns, and dialects across cultures, ethnic groups, geographic regions, and social roles.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

Multiple copies of literature books

- Literature Circle Roles

- Discussion Director

- Vocabulary Enricher

- Literary Luminary

- Literature Circle Process

- Self-Reflection: Taking Part in a Group (optional instead of online version)

Preparation

- Review the basic literature circle strategy, using the Websites linked in the Resources section. Before you begin the lesson, you should have a strong working knowledge of how the strategy works.

- Preview and read the books that students will choose among for this lesson so that you are familiar with the plot and literary elements. According to Hill, Johnson and Noe (1995), it is best to choose books that arouse emotions, are well-written, and are meaningful (113). The books should reflect students' reading levels as well. Gather copies of the books for each student group.

- If desired, make overhead transparencies of the Literature Circle Roles and Literature Circle Process . Alternately, you might write the information on chart paper or the board.

- Make copies of the Literature Circle Role Sheets ( Discussion Director , Vocabulary Enricher, Literary Luminary , and Checker ) for students to use independently and as they practice. Overhead transparencies of the forms may also be useful as the class explores the requirements of each task.

- Make copies of the Self-Reflection Worksheet , or if students will complete the self-reflection online, test the Online Self-Reflection Checklist on your computers to familiarize yourself with the tool and ensure that you have the Flash plug-in installed. You can download the plug-in from the technical support page.

Student Objectives

Students will

- discuss, define, and explore unfamiliar words.

- predict text events using previous knowledge and details in the text.

- use evidence in text to verify predictions.

- ask relevant and focused questions to clarify understanding.

- respond to questions and discussion with relevant and focused comments.

- paraphrase and summarize information from the text.

- identify and analyze literary elements in text.

Session One

- Introduce literature circles by explaining they are "groups of people reading the same book and meeting together to discuss what they have read" (Peralta-Nash and Dutch 30).

- Emphasize the student-centered collaborative nature of the reading strategy by discussing how the strategy places students "in charge of leading their own discussions as well as making decisions for themselves" (Peralta-Nash and Dutch 30). Share some of the ways that students will work independently (e.g., choosing the text the group will read, deciding on the questions that the group will discuss about the text).

Discussion Director creates questions to increase comprehension asks who, what, why, when, where, how, and what if Vocabulary Enricher clarifies word meanings and pronunciations uses research resources Literary Luminary guides oral reading for a purpose examines figurative language, parts of speech, and vivid descriptions Checker checks for completion of assignments evaluates participation helps monitor discussion for equal participation

- Preview the way that literature circles work for students, sharing the Literature Circle Process on the overhead projector or chart paper. Alternately, pass out copies for students to refer to.

- Explain that the class will practice each of the roles before students try the tasks on their own.

- Choose a short book with at least eight chapters to read as a whole class, beginning during the next class session.

Session Two

- Review basic information about literature circles.

- Explain that during this session, you will act as the Discussion Director to demonstrate how to do the task.

- creates questions to increase comprehension

- asks who, what, why, when, where, how, and what if

- Pass out copies of the Discussion Director role sheet and preview the information it contains.

- Read Chapter 1 of the text chosen during the previous session together.

- Demonstrating the Discussion Director Role, pause during the reading, as appropriate, to add details to the Discussion Director role sheet; or complete the Discussion Director role sheet after the reading is complete.

- Re-read the questions on the Discussion Director role sheet and make any revisions.

- Demonstrate how the Discussion Director would use the Discussion Director role sheet to lead discussion.

- Allow time to discuss the first chapter freely in order to show how discussion of questions and ideas that are not on the sheet is also appropriate.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make observations about how the Discussion Director role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Three

- Have students get out copies of the Discussion Director role sheet and review the information it contains.

- Explain that during this session, everyone will have a chance to practice being a Discussion Director.

- Ask students to recall how you recorded information on the Discussion Director role sheet during the previous session in order to establish the expectations for this session.

- Read Chapter 2 of the text together.

- Working in the Discussion Director Role, have students pause during the reading to add details to their copies of the Discussion Director role sheet; or complete the Discussion Director role sheet after the reading is complete.

- After the chapter has been read, have students re-read the questions on the Discussion Director role sheet and make any revisions.

- Arrange the class in small groups of 4-6 students each. These groups are simply for practice, so they can be formed informally if desired.

- Explain that each group member will serve as the Discussion Director for about 5 minutes.

- To make sure the process runs smoothly, have group members arrange turn-taking by deciding who will go first, second, third, and so forth.

- Have the first Discussion Director begin discussion. Watch the time so that you can cue students to change roles. Provide support and feedback as appropriate.

- After 5 minutes have passed, ask the second person take over as Discussion Director.

- Repeat this process until everyone in the class has had a chance to practice the Discussion Director role.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make any additional observations about how the Discussion Director role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Four

- Explain that during this session, you will act as the Vocabulary Enricher to demonstrate how to do the task.

- clarifies word meanings and pronunciations

- uses research resources

- Point out the classroom dictionaries and other resources students can use as they serve in this role.

- Pass out copies of the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet and preview the information it contains.

- Read Chapter 3 of the text together.

- Demonstrating the Vocabulary Enricher Role, pause during the reading, as appropriate, to add details to the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet; or complete the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet after the reading is complete.

- Re-read the questions on the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet and make any revisions.

- Demonstrate how the Vocabulary Enricher would use the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet to participate in the discussion.

- Allow time to discuss the chapter freely in order to show how discussion of questions and ideas that are not on the sheet is also appropriate.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make observations about how the Vocabulary Enricher role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Five

- Have students get out copies of the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet and review the information it contains.

- Remind students of the classroom dictionaries and other resources they can use as they serve in this role.

- Explain that during this session, everyone will have a chance to practice being a Vocabulary Enricher.

- Ask students to recall how you recorded information on the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet during the previous session in order to establish the expectations for this session.

- Read Chapter 4 of the text together.

- Working in the Vocabulary Enricher Role, have students pause during the reading to add details to their copies of the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet; or complete the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet after the reading is complete.

- After the chapter has been read, have students re-read the questions on the Vocabulary Enricher role sheet and make any revisions.

- Explain that each group member will serve as the Vocabulary Enricher for about 5 minutes.

- Have the first Vocabulary Enricher begin discussion. Watch the time so that you can cue students to change roles. Provide support and feedback as appropriate.

- After 5 minutes have passed, ask the second person take over as Vocabulary Enricher.

- Repeat this process until everyone in the class has had a chance to practice the Vocabulary Enricher role.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make any additional observations about how the Vocabulary Enricher role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Six

- Explain that during this session, you will act as the Literary Luminary to demonstrate how to do the task.

- guides oral reading for a purpose

- examines figurative language, parts of speech, and vivid descriptions

- Pass out copies of the Literary Luminary role sheet and preview the information it contains.

- Read Chapter 5 of the text together.

- Demonstrating the Literary Luminary Role, pause during the reading, as appropriate, to add details to the Literary Luminary role sheet; or complete the Literary Luminary role sheet after the reading is complete.

- Re-read the questions on the Literary Luminary role sheet and make any revisions.

- Demonstrate how the Literary Luminary would use the Literary Luminary role sheet to participate in the discussion.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make observations about how the Literary Luminary role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Seven

- Have students get out copies of the Literary Luminary role sheet and review the information it contains.

- Explain that during this session, everyone will have a chance to practice being a Literary Luminary.

- Ask students to recall how you recorded information on the Literary Luminary role sheet during the previous session in order to establish the expectations for this session.

- Read Chapter 6 of the text together.

- Working in the Literary Luminary Role, have students pause during the reading to add details to their copies of the Literary Luminary role sheet; or complete the Literary Luminary role sheet after the reading is complete.

- After the chapter has been read, have students re-read the questions on the Literary Luminary role sheet and make any revisions.

- Explain that each group member will serve as the Literary Luminary for about 5 minutes.

- Have the first Literary Luminary begin discussion. Watch the time so that you can cue students to change roles. Provide support and feedback as appropriate.

- After 5 minutes have passed, ask the second person take over as Literary Luminary.

- Repeat this process until everyone in the class has had a chance to practice the Literary Luminary role.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make any additional observations about how the Literary Luminary role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Eight

- Explain that during this session, you will act as the Checker to demonstrate how to do the task.

- checks for completion of assignments

- evaluates participation

- helps monitor discussion for equal participation

- Pass out copies of the Checker role sheet and preview the information it contains.

- Pass out copies of the other three role sheets: Discussion Director , Vocabulary Enricher , and Literary Luminary . Every student should have one sheet, but they will not all have the same sheet.

- Explain that for you to have information to record on the Checker role sheet, you need students in the class to take on the other roles.

- Read Chapter 7 of the text together.

- Pause during the reading, as appropriate, to allow students to add details to the different role sheets that they have; or have students complete the different role sheets after the reading is complete.

- When the chapter is finished, have students re-read the questions on their role sheets and make any revisions.

- Ask student volunteers to lead the class in discussion, serving in the role that they have prepared for.

- As students complete their role, demonstrate how the Checker would use the Checker role sheet to participate in the discussion. To include students more in the assessment, you might ask class members to talk about the work that each student volunteer does.

- Take advantage of the opportunity to talk about positive, constructive feedback and to warn against mean or bullying comments.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make observations about how the Checker role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

Session Nine

- Choose 6 or more students to participate as example literature circle groups. Select students who understand each of the roles that they are to complete well, and who will be able to understand the Checker role without as much practice as the rest of the class will have. You can ask for volunteers to serve these roles, but be sure that you choose volunteers who are confident about their ability to serve in the roles.

- Arrange the student volunteers in two small groups of model literature circles. Groups will switch after 5 minutes so that everyone in the classroom can practice the Checker role.

- Give the student volunteers copies of the the relevant role sheets: Discussion Director , Vocabulary Enricher , and Literary Luminary .

- Have students get out copies of the Checker role sheet and review the information it contains.

- Explain that during this session, everyone will have a chance to practice being a Checker.

- Ask students to recall how you recorded information on the Checker role sheet during the previous session in order to establish the expectations for this session.

- Read Chapter 8 of the text together.

- Pause during the reading, as appropriate, to allow student volunteers to add details to the different role sheets that they have; or have students complete the different role sheets after the reading is complete.

- When the chapter is finished, have student volunteers re-read the questions on their role sheets and make any revisions.

- Ask student volunteers to complete a literature circle discussion of the chapter for other students to observe, serving in the role that they have prepared for. If desired, you might allow students to be creative and perform at levels other than their best work. For instance, one student volunteer might participate as an uncooperative group member or as a member who has not read the text.

- As students complete their role, have class members use the Checker role sheet to record details on the discussion. To include students more in the assessment, you might ask class members to talk about the work that each student volunteer does.

- After 5 minutes have passed, have the example discussion group switch so that the second group takes over.

- Repeat the discussion process with the remaining students in the class taking on the Checker role.

- Once the second round of checking is complete, have students share observations and discuss the feedback they have recorded on the Checker role sheet.

- Again, reinforce positive, constructive feedback and comments.

- After discussion is complete, ask students to make any additional observations about how the Checker role works. Answer any questions that they have about the role.

- If there are remaining issues on the chapter that students want to discuss, be sure to allow time for this exploration as well.

- Explain that during following class sessions, students will work in literature circles independently.

- If the text students have read is complete, explain that students will begin a new book during the next session. If chapters remain, explain that groups will continue reading the text during the next session.

Session Ten

- If students are beginning new books, share basic details about the available texts and have students choose the books that they want to read.

- Arrange students in literature circle groups, based on book choice if students are beginning new texts, or based on similar interests or mixed abilities if the class is continuing with the text used for demonstration.

- Give each group copies of the Literature Circle Roles sheets, and ask students to choose the roles that they will complete for this session.

- Answer any questions, and then have students begin the reading and discussion process.

- As students work, circulate among the groups taking anecdotal data about their work and providing any support or feedback on the Literature Circle Roles . Remember that this is a student-centered discussion process, so take the role of a facilitator during these sessions, rather than that of a group member or instructor.

- At the end of the session, have groups rotate the literature circle roles.

Following Sessions

- Have students continue the process of reading the texts and rotating the literature circle roles until the books are complete.

- Provide some structural scheduling so that students know how much reading and work they should accomplish during each literature circle meeting.

- When books are finished, set aside a day for groups to share information about their reading, and then form new groups around new reading choices.

- Before students move on to a new book, have them complete the Self-Reflection Worksheet or use the Online Self-Reflection Checklist . When students begin the next book, ask them to use this self-reflection to think about how they participate with their new literature circle groups.

- Once students understand the basics of literature circles, try the ReadWriteThink lesson Literature Circle Roles Reframed: Reading as a Film Crew , which substitutes film production roles for the traditional literature circle roles.

- Ask Vocabulary Enrichers to choose 2-3 words from the reading and create pages for the words using the Alphabet Organizer . Groups can compile all pages created using the tool to compose a focused dictionary for the text. The dictionary might be shelved in the classroom library with the specific book students have read, so that others in the classroom can use the resource.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- As students work, take notes on their participation and engagement. Remember that discussion topics should grow naturally from students’ interests and connections to the text. Their group meetings should be open, natural conversations about books. Personal connections, digressions, and open-ended questions are welcome.

- Provide feedback to individual students in conferences and interviews. Base feedback on the feedback indicated on the Checker Role Sheets completed during the literature circle sessions as well as on your own observations. Suggest ways that students can improve their participation in the groups, pointing to the different role sheets that they have completed and relying on your anecdotal notes. Make connections to the Self-Reflection Worksheet or Online Self-Reflection Checklist that students complete when they finish the books. Encourage students to brainstorm strategies they can try in future literature circle meetings to improve their participation.

- Lesson Plans

- Calendar Activities

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

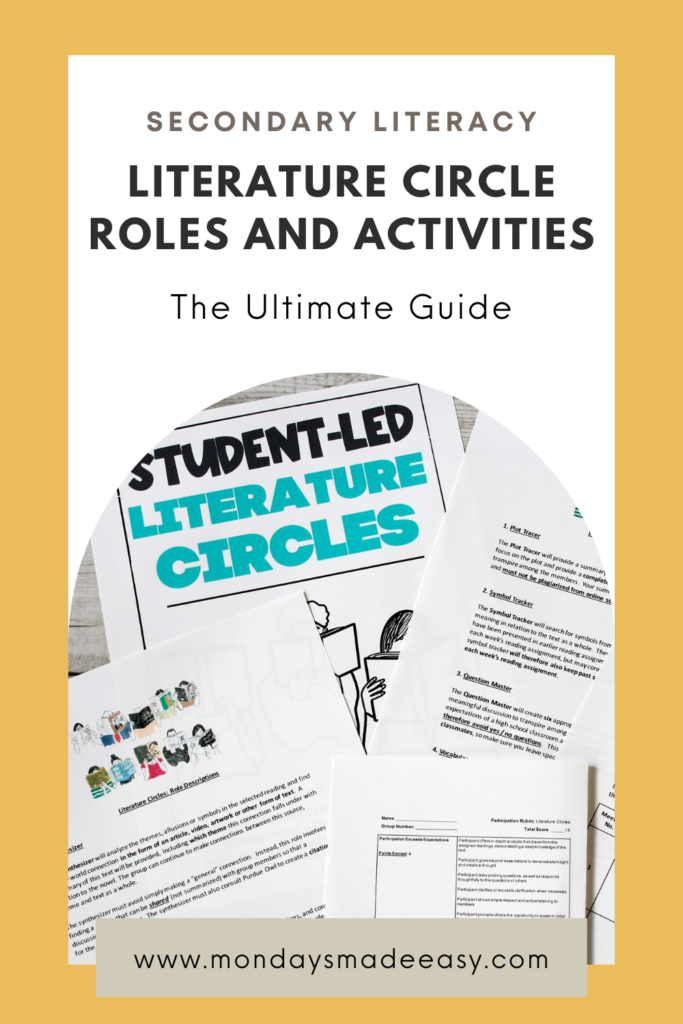

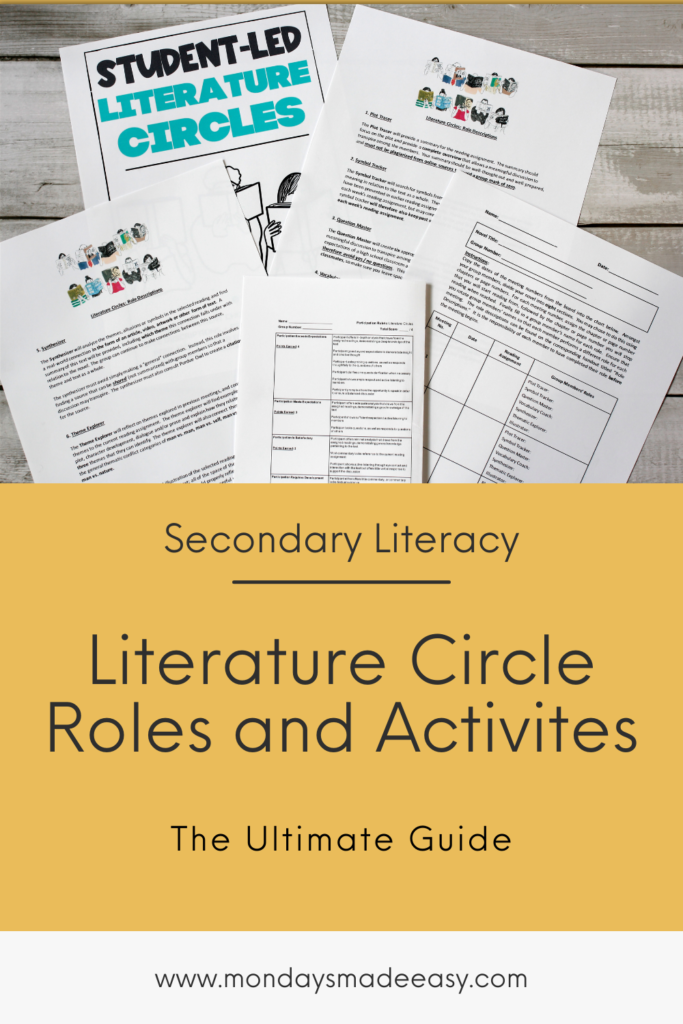

Literature Circle Roles and Activities: The Ultimate Guide

Classroom Management , Literature Circles , Secondary Literacy

In my first few years of teaching, I was constantly looking for ways to improve literature circles. I wanted literature circle roles that were differentiated, but also engaging for my students. I wanted to instill responsibilities that would mirror the reading strategies we were developing in our reading curriculum. Last but not least, I wanted my students to take initiative and hold each other accountable. So I did my research, and I wound up with this guide to literature circles .

This blog post explores some frequently asked questions about literature circles . It also shares activities and strategies for leading literature circles with older students, including engaging roles for literature circles .

Leading Literature Circles: Frequently Asked Questions

Do i need to pick books that i’ve read.

In order to assess students, it might seem like you’re responsible to read the book first. Thankfully, the answer is no – you do not need to pick books for literature circles that you’ve read! This is because the goal of literature circles is to facilitate peer-based learning . Since students will be learning from one another, it will not be your responsibility to guide them through the literary analysis.

How will I assess literature circles if I haven’t read the books?

The goal of peer-based learning is to have students build a shared understanding of the text . When assessing literature circles, determine what you think is important to evaluate. For example, if your curriculum is promoting higher-level thinking, then the goal is not for students to simply retell the story. This means you will not need to be able to re-tell it, either!

You can assess literature circles with one-pagers, overarching discussion questions , and final projects that require a strong understanding of the text. These assessments can focus on students’ critical thinking and text connections .

Here are some great resources for assessing literature circles :

- Elementary school (grades 4-6) : Draw from a number of student reflection and assessment one-pagers in this elementary school literature circles unit .

- Middle school (grades 6-8) : Prompt students to write a paragraph in which they reflect on their reading by writing a “ Retell, Relate, Reflect, Review” book report .

- High school (grades 9-12) : Have students focus on the theme and characterization within the novel by creating a movie trailer . Students can also explore different inquiry-based literature circle roles using this high school literature circles unit .

Do students need literature circle roles?

There is truly no right answer to this question. The benefits of liteature circle roles are that they offer structure, promote responsibility (which may improve attendance), and practice different reading strategies .

The disadvantage to literature circle roles is that they may stifle conversation and creativity ; a study from the Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy reported that students would read responses from their role sheets and “[did] not react to each other or question each other; instead, they simply [gave] each other their answers.”

If you are finding that your students are stifled by roles, the alternative would be to teach them how to lead their own group discussions . To do so, you can use a group discussion outline with stentence stems and self-assessment tools. Students can rotate through the role of notating the discussion with their peers. Through modelling this process, students can sucessfully take on the resposibility of leading and documenting their discussions.

My students are all at different reading levels. Should I still use literature circles?

Yes! Research from the International Reading Association concluded that literature circles are a great strategy for neurodivergent students, struggling readers, and accelerated learners alike .

How do you organize literature circle meetings?

You can use a graphic organizer to schedule literature circle meetings ; this graphic organizer can also indicate which reading assignments need to be completed for which meeting. I instruct students to divide the page number of their novel by the number of meetings within the graphic organizer. Students can use that as a guideline to establish how many chapters will be covered in each reading assignment.

Students can then note the literature circle roles for each week in the graphic organizer. I have every student fill out the graphic organizer so that they all know their role for each meeting.

Can students complete the same literature circle roles every week?

This depends on your students and the roles they wish to continually assume. Some roles, like the illustrator, are especially suitable for particular students. It may be a good opportunity for them to utilize their strengths . This is especially true if you are creating groups of students with diverse learning profiles.

In my classroom, I make them switch their roles each week. Even though they might not particularly love a role, it is beneficial for them to step outside of their comfort zone . It also avoids the predictability of completing the same tasks for each reading assignment.

How do teachers assign grades for literature circles?

You can assign both a group grade and an individual grade for literature circles. The group grade can be based on group assignments and activities from literature circle meetings . You can use the group grade as the basis for adjusting individual grades for each student. These adjustments can be based on their performance during their literature circle roles. It can also include peer feedback from peer evaluation forms .

Wrapping up with Literature Circles

I like to finish my literature circle unit with a final project . An assignment that students really enjoy is creating movie trailers for their novels. This project is a great assessment because it prompts students to consider important elements of the novel , like characterization and theme. Since they don’t want to spoil the plot, it also encourages students to avoid simple summaries . As a bonus, showcasing these trailers also sparks extracurricular reading for students who are inspired by their classmates’ work.

If you’re just getting started with literature circles or are looking for more resources and activities to lead your unit, be sure to check out Mondays Made Easy’s Literature Circle Bundle . This bundle includes literature circle roles, rubrics, discussion activities, and the movie trailer project mentioned above.

Reader Interactions

[…] teaching literature circles or simply looking for a fresh approach, you may also be interested in The New Teacher’s Guide to Literature Circles on the Mondays Made Easy […]

[…] summative assessment for any novel. Furthermore, it serves as a fantastic summative assessment for literature circles or independent novel […]

Literature Circles to Improve Reading Motivation and Skill

- Nurhaeda Gailea Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Indonesia

- Sutrisno Sadji Evenddy Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Indonesia

- Hani Haeroni Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Indonesia

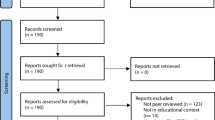

The objective of this research is to find out the improvement of reading motivation and skill by using literature circles. The researcher used classroom action research. The sample of this research were the eleventh grade of SMAN 1 Cinangka students. The researcher found that there is a significant improvement in reading motivation and skill by using literature circles. In the first cycle, students reading skill improved 42,9%, and the students reading motivation improved 41,%. In the second cycle gradually students reading skill improved 68,6%, and the students reading motivation improved 80,%. In the third cycle, students reading skill improved 91,4%, and the students reading motivation improved 91,4,%. It means that there is a significant improvement of reading motivation and skill which focused on discerning the main idea, specific information, understanding the sequence, and inference. All these suggest that improving reading motivation and skill by using literature circles is highly encouraged.

Bede, S. (2010). The Impact of Literature Circles. Bowling Green State University .

Bendu, C. G. (2013). A Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Based Literature Circle (LC) Model: Effects on Higher-Order Reading Comprehension Skills and Student Engagement in Diverse Sixth-Eighth Grade Classrooms. Department of Educational Administration, Foundations and Psychology University of Manitoba Winnipeg.

Bernhardt, E. B. (2011). Understanding Advanced Second- Language Reading. New York: Routledge.

Briggs, S. R. (2010). Using Literatue Circles to Increase Reading Comprehension in Third Grade Elementary School. Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Education, Dominican University of California, School of Education and Counseling Psychology, California.

Clarke, L. (2014). The Impact of Literature Circles on Student. Melbourne: Melbourne Graduate School of Education The University of Melbourne.

Daniels, H. (2002). Literature circles: Voice and Choice in book Clubs & Reading Group. Chicago: Pembroke Publishers Limited.

Edmondson, E. (2012). Wiki Literature Circles: Creating Digital Communities. English Journal, 101.

Ferris, J. S. (2009). Teaching Readers of English Students, Text and Context. New York: Routledge.

Grabe, W. (2009). Reading In A Second Language: Moving From Theory To Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graesser, A. C. (2007). An Introduction to Strategic Reading Comprehension. (D. S. McNamara, Penyunt.) London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Guthrie, J. T. (2004). Classroom Contexts for Engaged Reading: An Overview. (A. W. John T. Guthrie, Ed.) New Jersey, United States of America: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

H. Timoty Blumm, L. L. (2015, July 2). Literature Circles: A Tool for self Determination In One Middle School inclusive Classroom. Remedial and Special Education, 23.

Karami, H. (2008). Reading Startegies: What are they? retrieved March 29, 2018, from httpsfiles.eric.ed.govfulltextED502937.pd

Karatay, H. (2017, July 26). The Effect of Literature Circles on Text Analysis and Reading Desire. International Journal of Higher Education, 6, No. 5; 2017, 65.

Knol, C. L. (2000, April 4). Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. retrieved from http://scholar works.gvsu. edu/theses: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/497

Linse, C. T. (2005). Practical English Language Teaching: Young Learners. New York: MacGraw-Hill Companies.

Meredith, J. (2015). The Effects of Literature Circles on Second Graders’ Reading Comprehension and Motivation. Goucher College, Degree of Master of Educationin in Education Goucher College.

Middleton, M. E. (2011). Reading Motivation and Reading Comprehension. Ohio: Ohio State University.

Smidt, J. C. (2002). Dictionary Of Language Teaching & Applied Linguistics. London: Longman.

Smiles, T. (2005). Student Engagement Within Peer-led Literature Circles: Exploring the Thought Styles of Adolescents. The University of Arizona, Department of Language, Reading, and Culture. The University of Arizona.

Tugman, H. (2010). Literature Discussion Group And Reading Comprehension. Michigan: Northen Michigan University.

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2022 Nurhaeda Gailea, Sutrisno Sadji Evenddy, Hani Haeroni

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

By submitting the manuscript of the article, the authors agree with this policy with no specific document sign-off required .

The authors certify that:

- if the manuscript is co-authored, they are authorized by their co-authors to enter into these arrangements.

- the work described has not been formally published before in a registered ISSN or ISBN media, except in the form of an abstract or as part of a published lecture, review, or thesis.

- it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere,

- its publication has been approved by all the author(s) and by the responsible authorities – tacitly or explicitly – of the institutes where the work has been carried out.

- they secure the right to reproduce any material that has already been published or copyrighted elsewhere (it does not infringe the rights of others).

- they agree to Ethical Lingua license and copyright agreement.

All articles published by Ethical Lingua are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

License and Copyright Agreement

- Authors retain copyright and other proprietary rights related to the article.

- Authors retain the right and are permitted to use the substance of the article in own future works, including lectures and books.

- Authors grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in Ethical Lingua .

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in Ethical Lingua .

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post or self-archive their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work.

- Focus and Scope

- Publication Ethics

- Peer Review Process

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Policy

- Indexing and Abstracting

- Privacy Statement

- Author Fees

- Plagiarism Check

Editorial Statistics 2020 Editorial Statistics 2019 Information for Authors Information for Reviewers

ISSN 2540-9190 (Online) ISSN 2355-3448 (Print)

Published by

Accreditation by Sinta

- Satire Expressions in Animal Farm Novel by George Orwel : A Semantic Study 125

- Defining Plagiarism: A Literature Review 121

- Metaphor in The Folklore Album by Taylor Swift : A Semantics Study 85

- Flipped Classroom Learning Model: Implementation and Its Impact on EFL Learners’ Satisfaction on Grammar Class 49

- Fitzgerald’s Critiques on American Capitalism in His “The Great Gatsby” 43

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Furr (2004) d efined literature circles as sm all, peer-led reading groups that provide a f r a m e w o r k f o r m e m b e r s t o r e a d t h e s a m e s t o r y , p o e m , a r t i c l e o r ...

To improve the peer review process, the authors decided to change it into a multi-party oral, opinion gap task. Mimicking literature circles, we put students into teams of three and asked them to follow an expanding sequence of Monologue-Dialogue- Discussion (MDD) to discuss each essay.

1983). Literature circles are effective instruc - tional tools that address this challenge. Be-cause literature circles are student-directed, they provide students with space to enact the literacy practices of their communities. When implementing literature circles in a first-grade bilingual classroom, Mar-tinez-Roldán and López-Robertson (1999)

1 INTRODUCTION. Literature circles, reading clubs (Daniels, 2002), or peer-led small group discussions of assigned reading materials (Thomas & Kim, 2019), have been widely implemented to provide students with more opportunities to develop their reading ability at their own pace.Pedagogically speaking, Widodo contends that literature circles serve as a springboard for students to read the ...

What are peer-review circles? In writing, peer review is another term for peer assessment that supports academic writing and writer's review skills. It carries Vygotsky's theory of social interaction in learning (Vygotsky, 1978). It has been evolved in many ways, such as the literature circle (see Ferdiansyah et al., 2020;

Literature circles — a small group of students that gathers to discuss a book, much like a book club — are not a new idea , and in fact, remain quite popular because they are incredibly effective . Indeed, many studies of developing reading comprehension, including those by Harvard Graduate School of Education professor Catherine Snow ...

Literature circles (LCs) are "small, peer-led discussion groups whose members have chosen to read the same story, poem, article, or book" (Daniels 2002: 2).The word "peer" in this quotation denotes correctly that LCs generally refer to reading groups as practiced in schools, in contrast to book clubs, which are known more as reading groups held in private homes.

(2020), Literature circles are peer-led discussions of written texts in which the students, especially L2 learners, express their opinions and ideas about the story they have read in English.

To critically review the way literature circles promote collaborative learning in the EFL classroom. ... or peer group that wishes to discuss their learning and understanding, making literature circles very successful (Daniels). This work therefore shows transitioning of books clubs to literature circles as a natural transition that

The result evidently shows that literature circles contribute a significant effect to improve students' reading comprehension. This study reports an experimental study to see the effect of literatures circles to improve reading comprehension of English department students of State Islamic Institute (IAIN) of Samarinda. A quasi experimental research using nonrandomized control group pretest ...

Furr (2004) defined literature circles as small, peer-led reading groups that provide a framework for members to read the same story, poem, article or book and have meaningful discussions.

Abstract. This article reports the findings of ethnographic classroom research on the deployment of literature circles in English reading classes in the vocational secondary education sector in Indonesia. Grounded in micro-interac-tional, thematic, and discourse analyses, empirical findings showed that the students engaged actively in text ...

Literature circles use the student role of Literary Luminary as opportunity for students to look at. quotes, details, sections of text, and passages that are crucial for the reader to focus on as well as. analyze to deepen their understanding. According to Marchiando (2013), "Literary luminaries.

Literature circles are a topic of interest to various literacy educators, and their use has been discussed in a variety of academic journals, conference papers, and workshops. ... procedures for implementing literature circles and to review some recent findings regarding the benefits of literature circles on students' learning. ED469925 2002-10 ...

This study was designed to determine how literature circles effect reading comprehension and student motivation towards reading. After collecting and analyzing the data over the course of three weeks, the researcher determined that the implementation of literature circles increased student motivation towards reading and deepened comprehension.

This study presents a systematic literature review on the contributions of literature circles based on a number of published researches in several refereed international journals available in various online databases. It aims to identify the contributions on the use of the method to the teaching of Literature among students of various grade/year levels. The data which was plotted on the ...

This article examines the effectiveness of Harvey Daniels's literature circles, a student-centered and collaborative approach used primarily in the lower grades, as a tool for accessing the reading process and accessing texts. Levy reviews how this pedagogical model with its structured, scaffolded role sheets, which frame the literature ...

The positive peer pressure that the members of each group placed on each other contributed to each student's accountability to the rest of the group. (36) ... Review the basic literature circle strategy, using the Websites linked in the Resources section. Before you begin the lesson, you should have a strong working knowledge of how the ...

This is because the goal of literature circles is to facilitate peer-based learning. Since students will be learning from one another, it will not be your responsibility to guide them through the literary analysis. ... Review" book report. High school (grades 9-12): Have students focus on the theme and characterization within the novel by ...

Smiles, T. (2005). Student Engagement Within Peer-led Literature Circles: Exploring the Thought Styles of Adolescents. The University of Arizona, Department of Language, Reading, and Culture. The University of Arizona. Tugman, H. (2010). Literature Discussion Group And Reading Comprehension. Michigan: Northen Michigan University.

and peer-review sessions. The problem with this approach is that, too often, we assume that students know how to read actively, that reading has already been taught in the primary grades and therefore does not need to be the focus of our writing classes. We expect students to be able to assume the stance of experienced readers.

the whole class. From this point of view, literature circles is a form of independent reading, structured as collaborative small groups, and guided by reader response principles. These three main components underlie literature circles. Literature circles itself is small, peer-led discussion groups whose members have

This article describes a literature circle of seven pre-service teacher education students who read Al Capone Shines My Shoes (G. Choldenko, 2009). Students used the Internet to complete their roles, shared what they learned as they discussed the book, and then wrote about the digital experience. Four themes emerged from an analysis of the written responses with representative excerpts from ...

This review focuses on 'Book Club' (Raphael & McMahon, 1994) and 'Literature Circles' (Daniels, 2002), but it uses the general lowercase) term 'book clubs' to embrace both 'Literature Circles' and 'Book Club' activities, as well as small-group discussion activities that closely resemble either strategy but may leave out one ...

Keywords: Reading education, Reading comprehension, Literature circles, Book review, Prospective teacher, Reading desire. 1. Introduction. As is the case in all walks of life, in education the diversification and change of the tools, methods, and techniques used are inevitable as well.