Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What Is Literature and Why Do We Study It?

In this book created for my English 211 Literary Analysis introductory course for English literature and creative writing majors at the College of Western Idaho, I’ll introduce several different critical approaches that literary scholars may use to answer these questions. The critical method we apply to a text can provide us with different perspectives as we learn to interpret a text and appreciate its meaning and beauty.

The existence of literature, however we define it, implies that we study literature. While people have been “studying” literature as long as literature has existed, the formal study of literature as we know it in college English literature courses began in the 1940s with the advent of New Criticism. The New Critics were formalists with a vested interest in defining literature–they were, after all, both creating and teaching about literary works. For them, literary criticism was, in fact, as John Crowe Ransom wrote in his 1942 essay “ Criticism, Inc., ” nothing less than “the business of literature.”

Responding to the concern that the study of literature at the university level was often more concerned with the history and life of the author than with the text itself, Ransom responded, “the students of the future must be permitted to study literature, and not merely about literature. But I think this is what the good students have always wanted to do. The wonder is that they have allowed themselves so long to be denied.”

We’ll learn more about New Criticism in Section Three. For now, let’s return to the two questions I posed earlier.

What is literature?

First, what is literature ? I know your high school teacher told you never to look up things on Wikipedia, but for the purposes of literary studies, Wikipedia can actually be an effective resource. You’ll notice that I link to Wikipedia articles occasionally in this book. Here’s how Wikipedia defines literature :

“ Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction , drama , and poetry . [1] In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature , much of which has been transcribed. [2] Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.”

This definition is well-suited for our purposes here because throughout this course, we will be considering several types of literary texts in a variety of contexts.

I’m a Classicist—a student of Greece and Rome and everything they touched—so I am always interested in words with Latin roots. The Latin root of our modern word literature is litera , or “letter.” Literature, then, is inextricably intertwined with the act of writing. But what kind of writing?

Who decides which texts are “literature”?

The second question is at least as important as the first one. If we agree that literature is somehow special and different from ordinary writing, then who decides which writings count as literature? Are English professors the only people who get to decide? What qualifications and training does someone need to determine whether or not a text is literature? What role do you as the reader play in this decision about a text?

Let’s consider a few examples of things that we would all probably classify as literature. I think we can all (probably) agree that the works of William Shakespeare are literature. We can look at Toni Morrison’s outstanding ouvre of work and conclude, along with the Nobel Prize Committee, that books such as Beloved and Song of Solomon are literature. And if you’re taking a creative writing course and have been assigned the short stories of Raymond Carver or the poems of Joy Harjo , you’re probably convinced that these texts are literature too.

In each of these three cases, a different “deciding” mechanism is at play. First, with Shakespeare, there’s history and tradition. These plays that were written 500 years ago are still performed around the world and taught in high school and college English classes today. It seems we have consensus about the tragedies, histories, comedies, and sonnets of the Bard of Avon (or whoever wrote the plays).

In the second case, if you haven’t heard of Toni Morrison (and I am very sorry if you haven’t), you probably have heard of the Nobel Prize. This is one of the most prestigious awards given in literature, and since she’s a winner, we can safely assume that Toni Morrison’s works are literature.

Finally, your creative writing professor is an expert in their field. You know they have an MFA (and worked hard for it), so when they share their favorite short stories or poems with you, you trust that they are sharing works considered to be literature, even if you haven’t heard of Raymond Carver or Joy Harjo before taking their class.

(Aside: What about fanfiction? Is fanfiction literature?)

We may have to save the debate about fan fiction for another day, though I introduced it because there’s some fascinating and even literary award-winning fan fiction out there.

Returning to our question, what role do we as readers play in deciding whether something is literature? Like John Crowe Ransom quoted above, I think that the definition of literature should depend on more than the opinions of literary critics and literature professors.

I also want to note that contrary to some opinions, plenty of so-called genre fiction can also be classified as literature. The Nobel Prize winning author Kazuo Ishiguro has written both science fiction and historical fiction. Iain Banks , the British author of the critically acclaimed novel The Wasp Factory , published popular science fiction novels under the name Iain M. Banks. In other words, genre alone can’t tell us whether something is literature or not.

In this book, I want to give you the tools to decide for yourself. We’ll do this by exploring several different critical approaches that we can take to determine how a text functions and whether it is literature. These lenses can reveal different truths about the text, about our culture, and about ourselves as readers and scholars.

“Turf Wars”: Literary criticism vs. authors

It’s important to keep in mind that literature and literary theory have existed in conversation with each other since Aristotle used Sophocles’s play Oedipus Rex to define tragedy. We’ll look at how critical theory and literature complement and disagree with each other throughout this book. For most of literary history, the conversation was largely a friendly one.

But in the twenty-first century, there’s a rising tension between literature and criticism. In his 2016 book Literature Against Criticism: University English and Contemporary Fiction in Conflict, literary scholar Martin Paul Eve argues that twenty-first century authors have developed

a series of novelistic techniques that, whether deliberate or not on the part of the author, function to outmanoeuvre, contain, and determine academic reading practices. This desire to discipline university English through the manipulation and restriction of possible hermeneutic paths is, I contend, a result firstly of the fact that the metafictional paradigm of the high-postmodern era has pitched critical and creative discourses into a type of productive competition with one another. Such tensions and overlaps (or ‘turf wars’) have only increased in light of the ongoing breakdown of coherent theoretical definitions of ‘literature’ as distinct from ‘criticism’ (15).

One of Eve’s points is that by narrowly and rigidly defining the boundaries of literature, university English professors have inadvertently created a situation where the market increasingly defines what “literature” is, despite the protestations of the academy. In other words, the gatekeeper role that literary criticism once played is no longer as important to authors. For example, (almost) no one would call 50 Shades of Grey literature—but the salacious E.L James novel was the bestselling book of the decade from 2010-2019, with more than 35 million copies sold worldwide.

If anyone with a blog can get a six-figure publishing deal , does it still matter that students know how to recognize and analyze literature? I think so, for a few reasons.

- First, the practice of reading critically helps you to become a better reader and writer, which will help you to succeed not only in college English courses but throughout your academic and professional career.

- Second, analysis is a highly sought after and transferable skill. By learning to analyze literature, you’ll practice the same skills you would use to analyze anything important. “Data analyst” is one of the most sought after job positions in the New Economy—and if you can analyze Shakespeare, you can analyze data. Indeed.com’s list of top 10 transferable skills includes analytical skills , which they define as “the traits and abilities that allow you to observe, research and interpret a subject in order to develop complex ideas and solutions.”

- Finally, and for me personally, most importantly, reading and understanding literature makes life make sense. As we read literature, we expand our sense of what is possible for ourselves and for humanity. In the challenges we collectively face today, understanding the world and our place in it will be important for imagining new futures.

A note about using generative artificial intelligence

As I was working on creating this textbook, ChatGPT exploded into academic consciousness. Excited about the possibilities of this new tool, I immediately began incorporating it into my classroom teaching. In this book, I have used ChatGPT to help me with outlining content in chapters. I also used ChatGPT to create sample essays for each critical lens we will study in the course. These essays are dry and rather soulless, but they do a good job of modeling how to apply a specific theory to a literary text. I chose John Donne’s poem “The Canonization” as the text for these essays so that you can see how the different theories illuminate different aspects of the text.

I encourage students in my courses to use ChatGPT in the following ways:

- To generate ideas about an approach to a text.

- To better understand basic concepts.

- To assist with outlining an essay.

- To check grammar, punctuation, spelling, paragraphing, and other grammar/syntax issues.

If you choose to use Chat GPT, please include a brief acknowledgment statement as an appendix to your paper after your Works Cited page explaining how you have used the tool in your work. Here is an example of how to do this from Monash University’s “ Acknowledging the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence .”

I acknowledge the use of [insert AI system(s) and link] to [specific use of generative artificial intelligence]. The prompts used include [list of prompts]. The output from these prompts was used to [explain use].

Here is more information about how to cite the use of generative AI like ChatGPT in your work. The information below was adapted from “Acknowledging and Citing Generative AI in Academic Work” by Liza Long (CC BY 4.0).

The Modern Language Association (MLA) uses a template of core elements to create citations for a Works Cited page. MLA asks students to apply this approach when citing any type of generative AI in their work. They provide the following guidelines:

Cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it. Acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location. Take care to vet the secondary sources it cites. (MLA)

Here are some examples of how to use and cite generative AI with MLA style:

Example One: Paraphrasing Text

Let’s say that I am trying to generate ideas for a paper on Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” I ask ChatGPT to provide me with a summary and identify the story’s main themes. Here’s a link to the chat . I decide that I will explore the problem of identity and self-expression in my paper.

My Paraphrase of ChatGPT with In-Text Citation

The problem of identity and self expression, especially for nineteenth-century women, is a major theme in “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (“Summarize the short story”).

Works Cited Entry

“Summarize the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Include a breakdown of the main themes” prompt. ChatGPT. 24 May Version, OpenAI, 20 Jul. 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/d1526b95-920c-48fc-a9be-83cd7dfa4be5

Example Two: Quoting Text

In the same chat, I continue to ask ChatGPT about the theme of identity and self expression. Here’s an example of how I could quote the response in the body of my paper:

When I asked ChatGPT to describe the theme of identity and self expression, it noted that the eponymous yellow wallpaper acts as a symbol of the narrator’s self-repression. However, when prompted to share the scholarly sources that formed the basis of this observation, ChatGPT responded, “As an AI language model, I don’t have access to my training data, but I was trained on a mixture of licensed data, data created by human trainers, and publicly available data. OpenAI, the organization behind my development, has not publicly disclosed the specifics of the individual datasets used, including whether scholarly sources were specifically used” (“Summarize the short story”).

It’s worth noting here that ChatGPT can “ hallucinate ” fake sources. As a Microsoft training manual notes, these chatbots are “built to be persuasive, not truthful” (Weiss &Metz, 2023). The May 24, 2023 version will no longer respond to direct requests for references; however, I was able to get around this restriction fairly easily by asking for “resources” instead.

When I ask for resources to learn more about “The Yellow Wallpaper,” here is one source it recommends:

“Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper: A Symptomatic Reading” by Elaine R. Hedges: This scholarly article delves into the psychological and feminist themes of the story, analyzing the narrator’s experience and the implications of the yellow wallpaper on her mental state. It’s available in the journal “Studies in Short Fiction.” (“Summarize the short story”).

Using Google Scholar, I look up this source to see if it’s real. Unsurprisingly, this source is not a real one, but it does lead me to another (real) source: Kasmer, Lisa. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s’ The Yellow Wallpaper’: A Symptomatic Reading.” Literature and Psychology 36.3 (1990): 1.

Note: ALWAYS check any sources that ChatGPT or other generative AI tools recommend.

For more information about integrating and citing generative artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, please see this section of Write What Matters.

I acknowledge that ChatGPT does not respect the individual rights of authors and artists and ignores concerns over copyright and intellectual property in its training; additionally, I acknowledge that the system was trained in part through the exploitation of precarious workers in the global south. In this work I specifically used ChatGPT to assist with outlining chapters, providing background information about critical lenses, and creating “model” essays for the critical lenses we will learn about together. I have included links to my chats in an appendix to this book.

Critical theories: A targeted approach to writing about literature

Ultimately, there’s not one “right” way to read a text. In this book. we will explore a variety of critical theories that scholars use to analyze literature. The book is organized around different targets that are associated with the approach introduced in each chapter. In the introduction, for example, our target is literature. In future chapters you’ll explore these targeted analysis techniques:

- Author: Biographical Criticism

- Text: New Criticism

- Reader: Reader Response Criticism

- Gap: Deconstruction (Post-Structuralism)

- Context: New Historicism and Cultural Studies

- Power: Marxist and Postcolonial Criticism

- Mind: Psychological Criticism

- Gender: Feminist, Post Feminist, and Queer Theory

- Nature: Ecocriticism

Each chapter will feature the target image with the central approach in the center. You’ll read a brief introduction about the theory, explore some primary texts (both critical and literary), watch a video, and apply the theory to a primary text. Each one of these theories could be the subject of its own entire course, so keep in mind that our goal in this book is to introduce these theories and give you a basic familiarity with these tools for literary analysis. For more information and practice, I recommend Steven Lynn’s excellent Texts and Contexts: Writing about Literature with Critical Theory , which provides a similar introductory framework.

I am so excited to share these tools with you and see you grow as a literary scholar. As we explore each of these critical worlds, you’ll likely find that some critical theories feel more natural or logical to you than others. I find myself much more comfortable with deconstruction than with psychological criticism, for example. Pay attention to how these theories work for you because this will help you to expand your approaches to texts and prepare you for more advanced courses in literature.

P.S. If you want to know what my favorite book is, I usually tell people it’s Herman Melville’s Moby Dick . And I do love that book! But I really have no idea what my “favorite” book of all time is, let alone what my favorite book was last year. Every new book that I read is a window into another world and a template for me to make sense out of my own experience and better empathize with others. That’s why I love literature. I hope you’ll love this experience too.

writings in prose or verse, especially : writings having excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest (Merriam Webster)

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions- Spring 2024

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Faculty Notes Submission Form

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is Literature? || Definition & Examples

"what is literature": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is Literature? Transcript (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in Video; Click HERE for Spanish Transcript)

By Evan Gottlieb & Paige Thomas

3 January 2022

The question of what makes something literary is an enduring one, and I don’t expect that we’ll answer it fully in this short video. Instead, I want to show you a few different ways that literary critics approach this question and then offer a short summary of the 3 big factors that we must consider when we ask the question ourselves.

Let’s begin by making a distinction between “Literature with a capital L” and “literature with a small l.”

“Literature with a small l” designates any written text: we can talk about “the literature” on any given subject without much difficulty.

“Literature with a capital L”, by contrast, designates a much smaller set of texts – a subset of all the texts that have been written.

what_is_literature_little_l.png

So what makes a text literary or what makes a text “Literature with a capital L”?

Let’s start with the word itself. “Literature” comes from Latin, and it originally meant “the use of letters” or “writing.” But when the word entered the Romance languages that derived from Latin, it took on the additional meaning of “knowledge acquired from reading or studying books.” So we might use this definition to understand “Literature with a Capital L” as writing that gives us knowledge--writing that should be studied.

But this begs the further question: what books or texts are worth studying or close reading ?

For some critics, answering this question is a matter of establishing canonicity. A work of literature becomes “canonical” when cultural institutions like schools or universities or prize committees classify it as a work of lasting artistic or cultural merit.

The canon, however, has proved problematic as a measure of what “Literature with a capital L” is because the gatekeepers of the Western canon have traditionally been White and male. It was only in the closing decades of the twentieth century that the canon of Literature was opened to a greater inclusion of diverse authors.

And here’s another problem with that definition: if inclusion in the canon were our only definition of Literature, then there could be no such thing as contemporary Literature, which, of course, has not yet stood the test of time.

And here’s an even bigger problem: not every book that receives good reviews or a wins a prize turns out to be of lasting value in the eyes of later readers.

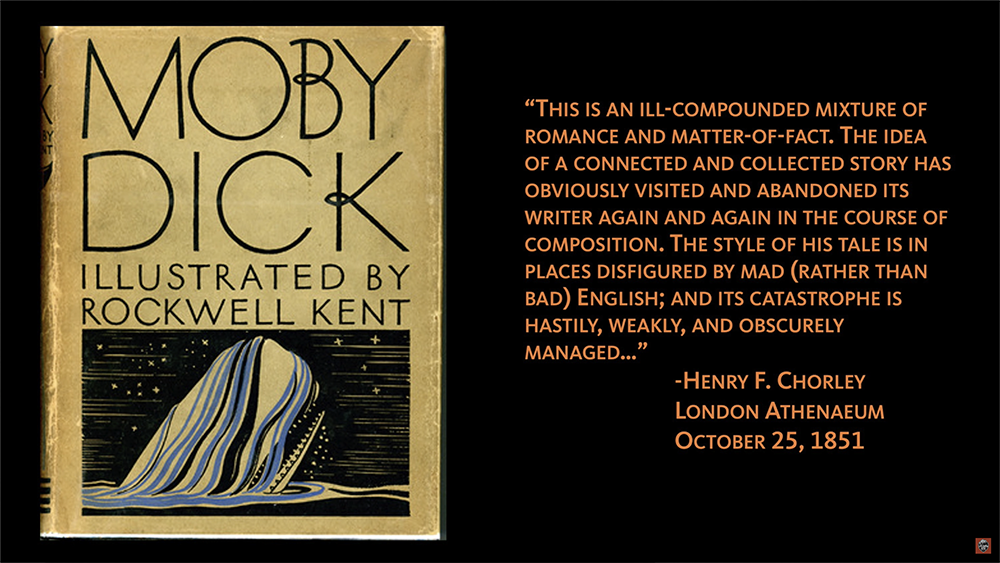

On the other hand, a novel like Herman Melville’s Moby-Di ck, which was NOT received well by critics or readers when it was first published in 1851, has since gone on to become a mainstay of the American literary canon.

moby_dick_with_quote.png

As you can see, canonicity is obviously a problematic index of literariness.

So… what’s the alternative? Well, we could just go with a descriptive definition: “if you love it, then it’s Literature!”

But that’s a little too subjective. For example, no matter how much you may love a certain book from your childhood (I love The Very Hungry Caterpillar ) that doesn’t automatically make it literary, no matter how many times you’ve re-read it.

Furthermore, the very idea that we should have an emotional attachment to the books we read has its own history that cannot be detached from the rise of the middle class and its politics of telling people how to behave.

Ok, so “literature with a capital L” cannot always by defined by its inclusion in the canon or the fact that it has been well-received so…what is it then? Well, for other critics, what makes something Literature would seem to be qualities within the text itself.

According to the critic Derek Attridge, there are three qualities that define modern Western Literature:

1. a quality of invention or inventiveness in the text itself;

2. the reader’s sense that what they are reading is singular. In other words, the unique vision of the writer herself.

3. a sense of ‘otherness’ that pushes the reader to see the world around them in a new way

Notice that nowhere in this three-part definition is there any limitation on the content of Literature. Instead, we call something Literature when it affects the reader at the level of style and construction rather than substance.

In other words, Literature can be about anything!

what_is_literature_caterpillar.png

The idea that a truly literary text can change a reader is of course older than this modern definition. In the English tradition, poetry was preferred over novels because it was thought to create mature and sympathetic reader-citizens.

Likewise, in the Victorian era, it was argued that reading so-called “great” works of literature was the best way for readers to realize their full spiritual potentials in an increasingly secular world.

But these never tell us precisely what “the best” is. To make matters worse, as I mentioned already, “the best” in these older definitions was often determined by White men in positions of cultural and economic power.

So we are still faced with the question of whether there is something inherent in a text that makes it literary.

Some critics have suggested that a sense of irony – or, more broadly, a sense that there is more than one meaning to a given set of words – is essential to “Literature with a capital L.”

Reading for irony means reading slowly or at least attentively. It demands a certain attention to the complexity of the language on the page, whether that language is objectively difficult or not.

In a similar vein, other critics have claimed that the overall effect of a literary text should be one of “defamiliarization,” meaning that the text asks or even forces readers to see the world differently than they did before reading it.

Along these lines, literary theorist Roland Barthes maintained that there were two kinds of texts: the text of pleasure, which we can align with everyday Literature with a small l” and the text of jouissance , (yes, I said jouissance) which we can align with Literature. Jouissance makes more demands on the reader and raises feelings of strangeness and wonder that surpass the everyday and even border on the painful or disorienting.

Barthes’ definition straddles the line between objectivity and subjectivity. Literature differs from the mass of writing by offering more and different kinds of experiences than the ordinary, non-literary text.

Literature for Barthes is thus neither entirely in the eye of the beholder, nor something that can be reduced to set of repeatable, purely intrinsic characteristics.

This negative definition has its own problems, though. If the literary text is always supposed to be innovative and unconventional, then genre fiction, which IS conventional, can never be literary.

So it seems that whatever hard and fast definition we attempt to apply to Literature, we find that we run up against inevitable exceptions to the rules.

As we examine the many problematic ways that people have defined literature, one thing does become clear. In each of the above examples, what counts as Literature depends upon three interrelated factors: the world, the text, and the critic or reader.

You see, when we encounter a literary text, we usually do so through a field of expectations that includes what we’ve heard about the text or author in question [the world], the way the text is presented to us [the text], and how receptive we as readers are to the text’s demands [the reader].

With this in mind, let’s return to where we started. There is probably still something to be said in favor of the “test of time” theory of Literature.

After all, only a small percentage of what is published today will continue to be read 10, 20, or even 100 years from now; and while the mechanisms that determine the longevity of a text are hardly neutral, one can still hope that individual readers have at least some power to decide what will stay in print and develop broader cultural relevance.

The only way to experience what Literature is, then, is to keep reading: as long as there are avid readers, there will be literary texts – past, present, and future – that challenge, excite, and inspire us.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Gottlieb, Evan and Paige Thomas. "What is Literature?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 3 Jan. 2022, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-literature-definition-examples. Accessed [insert date].

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

Literary Theory

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

Quick Reference

A body of written works related by subject-matter (e.g. the literature of computing), by language or place of origin (e.g. Russian literature), or by prevailing cultural standards of merit. In this last sense, ‘literature’ is taken to include oral, dramatic, and broadcast compositions that may not have been published in written form but which have been (or deserve to be) preserved. Since the 19th century, the broader sense of literature as a totality of written or printed works has given way to more exclusive definitions based on criteria of imaginative, creative, or artistic value, usually related to a work's absence of factual or practical reference (see autotelic). Even more restrictive has been the academic concentration upon poetry, drama, and fiction. Until the mid-20th century, many kinds of non-fictional writing—in philosophy, history, biography, criticism, topography, science, and politics—were counted as literature; implicit in this broader usage is a definition of literature as that body of works which—for whatever reason—deserves to be preserved as part of the current reproduction of meanings within a given culture (unlike yesterday's newspaper, which belongs in the disposable category of ephemera). This sense seems more tenable than the later attempts to divide literature—as creative, imaginative, fictional, or non-practical—from factual writings or practically effective works of propaganda, rhetoric, or didactic writing. The Russian Formalists' attempt to define literariness in terms of linguistic deviations is important in the theory of poetry, but has not addressed the more difficult problem of the non-fictional prose forms. See also belles-lettres , canon, paraliterature. For a fuller account, consult Peter Widdowson, Literature (1998).

From: literature in The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms »

Subjects: Literature

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'literature' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 02 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|193.7.198.129]

- 193.7.198.129

Character limit 500 /500

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.10: Literature (including fiction, drama, poetry, and prose)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 205491

- Lori-Beth Larsen

- Central Lakes College

Essential Questions for Literature

- How is literature like life?

- What is literature supposed to do?

- What influences a writer to create?

- How does literature reveal the values of a given culture or time period?

- How does the study of fiction and nonfiction texts help individuals construct their understanding of reality?

- In what ways are all narratives influenced by bias and perspective?

- Where does the meaning of a text reside? Within the text, within the reader, or in the transaction that occurs between them?

- What can a reader know about an author’s intentions based only on a reading of the text?

- What are enduring questions and conflicts that writers (and their cultures) grappled with hundreds of years ago and are still relevant today?

- How do we gauge the optimism or pessimism of a particular time period or particular group of writers?

- Why are there universal themes in literature–that is, themes that are of interest or concern to all cultures and societies?

- What are the characteristics or elements that cause a piece of literature to endure?

- What is the purpose of: science fiction? satire? historical novels, etc.?

- How do novels, short stories, poetry, etc. relate to the larger questions of philosophy and humanity?

- How we can use literature to explain or clarify our own ideas about the world?

- How does what we know about the world shape the stories we tell?

- How do the stories we tell about the world shape the way we view ourselves?

- How do our personal experiences shape our view of others?

- What does it mean to be an insider or an outsider?

- Are there universal themes in literature that are of interest or concern to all cultures and societies?

- What is creativity and what is its importance for the individual / the culture?

- What are the limits, if any, of freedom of speech?

Defining Literature

Literature, in its broadest sense, is any written work. Etymologically, the term derives from Latin litaritura / litteratura “writing formed with letters,” although some definitions include spoken or sung texts. More restrictively, it is writing that possesses literary merit. Literature can be classified according to whether it is fiction or non-fiction and whether it is poetry or prose. It can be further distinguished according to major forms such as the novel, short story or drama, and works are often categorized according to historical periods or their adherence to certain aesthetic features or expectations (genre).

Taken to mean only written works, literature was first produced by some of the world’s earliest civilizations—those of Ancient Egypt and Sumeria—as early as the 4th millennium BC; taken to include spoken or sung texts, it originated even earlier, and some of the first written works may have been based on a pre-existing oral tradition. As urban cultures and societies developed, there was a proliferation in the forms of literature. Developments in print technology allowed for literature to be distributed and experienced on an unprecedented scale, which has culminated in the twenty-first century in electronic literature.

Definitions of literature have varied over time. In Western Europe prior to the eighteenth century, literature as a term indicated all books and writing. [1] A more restricted sense of the term emerged during the Romantic period, in which it began to demarcate “imaginative” literature. [2]

Contemporary debates over what constitutes literature can be seen as returning to the older, more inclusive notion of what constitutes literature. Cultural studies, for instance, takes as its subject of analysis both popular and minority genres, in addition to canonical works. [3]

Major Forms

A calligram by Guillaume Apollinaire. These are a type of poem in which the written words are arranged in such a way to produce a visual image.

Poetry is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, prosaic ostensible meaning (ordinary intended meaning). Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its being set in verse; [4] prose is cast in sentences, poetry in lines; the syntax of prose is dictated by meaning, whereas that of poetry is held across metre or the visual aspects of the poem. [5]

Prior to the nineteenth century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines; accordingly, in 1658 a definition of poetry is “any kind of subject consisting of Rythm or Verses”. [6] Possibly as a result of Aristotle’s influence (his Poetics ), “poetry” before the nineteenth century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art. [7] As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition; [8] hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

Prose is a form of language that possesses ordinary syntax and natural speech rather than rhythmic structure; in which regard, along with its measurement in sentences rather than lines, it differs from poetry. [9] On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that ”

Novel : a long fictional prose narrative.

Novella :The novella exists between the novel and short story; the publisher Melville House classifies it as “too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story.” [10]

Short story : a dilemma in defining the “short story” as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative. Apart from its distinct size, various theorists have suggested that the short story has a characteristic subject matter or structure; [11] these discussions often position the form in some relation to the novel. [12]

Drama is literature intended for performance. [13]

Listen to this Discussion of the poetry of Harris Khalique . You might want to take a look at the transcript as you listen.

The first half of a 2008 reading featuring four Latino poets, as part of the American Perspectives series at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Listen to poetry reading of Francisco Aragón and Brenda Cárdenas

Listen to this conversation with Allison Hedge Coke, Linda Hogan and Sherwin Bitsui . You might want to look at the transcript as you listen. In this program, we hear a conversation among three Native American poets: Allison Hedge Coke, Linda Hogan and Sherwin Bitsui. Allison Hedge Coke grew up listening to her Father’s traditional stories as she moved from Texas to North Carolina to Canada and the Great Plains. She is the author of several collections of poetry and the memoir, Rock, Ghost, Willow, Deer. She has worked as a mentor with Native Americans and at-risk youth, and is currently a Professor of Poetry and Writing at the University of Nebraska, Kearney. Linda Hogan is a prolific poet, novelist and essayist. Her work is imbued with an indigenous sense of history and place, while it explores environmental, feminist and spiritual themes. A former professor at the University of Colorado, she is currently the Chickasaw Nation’s Writer in Residence. She lives in Oklahoma, where she researches and writes about Chickasaw history, mythology and ways of life. Sherwin Bitsui grew up on the Navajo reservation in Arizona. He speaks Dine, the Navajo language and participates in ceremonial activities. His poetry has a sense of the surreal, combining images of the contemporary urban culture, with Native ritual and myth.

Chris Abani : Stories from Africa

In this deeply personal talk, Nigerian writer Chris Abani says that “what we know about how to be who we are” comes from stories. He searches for the heart of Africa through its poems and narrative, including his own.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#oembed-1

Listen to Isabel Allende’s Ted Talk

As a novelist and memoirist, Isabel Allende writes of passionate lives, including her own. Born into a Chilean family with political ties, she went into exile in the United States in the 1970s—an event that, she believes, created her as a writer. Her voice blends sweeping narrative with touches of magical realism; her stories are romantic, in the very best sense of the word. Her novels include The House of the Spirits, Eva Luna and The Stories of Eva Luna, and her latest, Maya’s Notebook and Ripper. And don’t forget her adventure trilogy for young readers— City of the Beasts, Kingdom of the Golden Dragon and Forest of the Pygmies.

As a memoirist, she has written about her vision of her lost Chile, in My Invented Country, and movingly tells the story of her life to her own daughter, in Paula. Her book Aphrodite: A Memoir of the Senses memorably linked two sections of the bookstore that don’t see much crossover: Erotica and Cookbooks. Just as vital is her community work: The Isabel Allende Foundation works with nonprofits in the San Francisco Bay Area and Chile to empower and protect women and girls—understanding that empowering women is the only true route to social and economic justice.

You can read excerpts of her books online here: https://www.isabelallende.com/en/books

Read her musings. Why does she write? https://www.isabelallende.com/en/musings

You might choose to read one of her novels.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#oembed-2

Listen to Novelist Chimamanda Adichie . She speaks about how our lives, our cultures, are composed of many overlapping stories. She tells the story of how she found her authentic cultural voice — and warns that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk a critical misunderstanding.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#oembed-3

One Hundred Years of Solitu de

Gabriel García Márquez’s novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude” brought Latin American literature to the forefront of the global imagination and earned García Márquez the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature. What makes the novel so remarkable? Francisco Díez-Buzo investigates.

Gabriel García Márquez was a writer and journalist who recorded the haphazard political history of Latin American life through his fiction. He was a part of a literary movement called the Latin American “boom ,” which included writers like Peru’s Mario Vargas Llosa, Argentina’s Julio Cortázar, and Mexico’s Carlos Fuentes. Almost all of these writers incorporated aspects of magical realism in their work . Later authors, such as Isabel Allende and Salman Rushdie, would carry on and adapt the genre to the cultural and historical experiences of other countries and continents. García Máruqez hadn’t always planned on being a writer, but a pivotal moment in Colombia’s—and Latin America’s—history changed all that. In 1948, when García Márquez was a law student in Bogotá, Jorge Eliécer Gaítan , a prominent radical populist leader of Colombia’s Liberal Party, was assassinated. This happened while the U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall brought together leaders from across the Americas to create the Organization of American States (OAS) and to build a hemisphere-wide effort against communism. In the days after the assassination, massive riots, now called the bogotazo , occurred. The worst Colombian civil war to date, known as La Violencia , also broke out. Another law student, visiting from Cuba, was deeply affected by Eliécer Gaítan’s death. This student’s name was Fidel Castro. Interestingly, García Márquez and Castro—both socialists—would become close friends later on in life , despite not meeting during these tumultuous events. One Hundred Years of Solitude ’s success almost didn’t happen, but this article from Vanity Fair helps explain how a long-simmering idea became an international sensation. When Gabriel García Márquez won the Nobel Prize in 1982, he gave a lecture that helped illuminate the plights that many Latin Americans faced on a daily basis. Since then, that lecture has also helped explain the political and social critiques deeply embedded in his novels. It was famous for being an indigenous overview of how political violence became entrenched in Latin America during the Cold War.In an interview with the New Left Review , he discussed a lot of the inspirations for his work, as well as his political beliefs.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#h5p-12

Don Quixote

Mounting his skinny steed, Don Quixote charges an army of giants. It is his duty to vanquish these behemoths in the name of his beloved lady, Dulcinea. There’s only one problem: the giants are merely windmills. What is it about this tale of the clumsy yet valiant knight that makes it so beloved? Ilan Stavans investigates.

Interested in exploring the world of Don Quixote ? Check out this translation of the thrill-seeking classic. To learn more about Don Quixote ’s rich cultural history, click here . In this interview , the educator shares his inspiration behind his book Quixote: The Novel and the World . The travails of Don Quixote ’s protagonist were heavily shaped by real-world events in 17th-century Spain. This article provides detailed research on what, exactly, happened during that time.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#h5p-13

Midnight’s Children

It begins with a countdown. A woman goes into labor as the clock ticks towards midnight. Across India, people wait for the declaration of independence after nearly 200 years of British rule. At the stroke of midnight, an infant and two new nations are born in perfect synchronicity. These events form the foundation of “Midnight’s Children.” Iseult Gillespie explores Salman Rushdie’s dazzling novel.

At the stroke of midnight, the first gasp of a newborn syncs with the birth of two new nations. These simultaneous events are at the center of Midnight’s Children, a dazzling novel about the state of modern India by the British-Indian author Salman Rushdie . You can listen to an interview with Rushdie discussing the novel here . The chosen baby is Saleem Sinai, who narrates the novel from a pickle factory in 1977. As this article argues, much of the beauty of the narrative lies in Rushdie’s ability to weave the personal into the political in surprising ways. Saleem’s narrative leaps back in time, to trace his family history from 1915 on. The family tree is blossoming with bizarre scenes, including clandestine courtships, babies swapped at birth, and cryptic prophecies. For a detailed interactive timeline of the historical and personal events threaded through the novel, click here . However, there’s one trait that can’t be explained by genes alone – Saleem has magic powers, and they’re somehow related to the time of his birth. For an overview of the use of magical realism and astonishing powers in Mignight’s Children, click here. Saleem recounts a new nation, flourishing and founding after almost a century of British rule. For more information on the dark history of British occupation of India, visit this page. The vast historical frame is one reason why Midnight’s Children is considered one of the most illuminating works of postcolonial literature ever written. This genre typically addresses life in formerly colonized countries, and explores the fallout through themes like revolution, migration, and identity. Postcolonial literature also deals with the search for agency and authenticity in the wake of imposed foreign rule. Midnight’s Children reflects these concerns with its explosive combination of Eastern and Western references. On the one hand, it’s been compared to the sprawling novels of Charles Dickens or George Elliot, which also offer a panoramic vision of society paired with tales of personal development. But Rushdie radically disrupts this formula by adding Indian cultural references, magic and myth. Saleem writes the story by night, and narrates it back to his love interest, Padma. This echoes the frame for 1001 Nights , a collection of Middle Eastern folktales told by Scheherazade every night to her lover – and as Saleem reminds us, 1001 is “the number of night, of magic, of alternative realities.” Saleem spends a lot of the novel attempting to account for the unexpected. But he often gets thoroughly distracted and goes on astonishing tangents, telling dirty jokes or mocking his enemies. With his own powers of telepathy, Saleem forges connections between other children of midnight; including a boy who can step through time and mirrors, and a child who changes their gender when immersed in water. There’s other flashes of magic throughout, from a mother who can see into dreams to witchdoctors, shapeshifters, and many more. For an overview of the dazzling reference points of the novel, visit this page . Sometimes, all this is like reading a rollercoaster: Saleem sometimes narrates separate events all at once, refers to himself in the first and third person in the space of a single sentence, or uses different names for one person. And Padma is always interrupting, urging him to get to the point or exclaiming at his story’s twists and turns. This mind-bending approach has garnered continuing fascination and praise. Not only did Midnight’s Children win the prestigious Man Booker prize in its year of publication, but it was named the best of all the winners in 2008 . For an interview about Rushdie’s outlook and processed, click here. All this gives the narrative a breathless quality, and brings to life an entire society surging through political upheaval without losing sight of the marvels of individual lives. But even as he depicts the cosmological consequences of a single life, Rushdie questions the idea that we can ever condense history into a single narrative.

Tom Elemas : The Inspiring Truth in Fiction

What do we lose by choosing non-fiction over fiction? For Tomas Elemans, there’s an important side effect of reading fiction: empathy — a possible antidote to a desensitized world filled with tragic news and headlines.

What is empathy? How does story-telling create empathy? What stories trigger empathy in you? What is narrative immersion? Are we experiencing an age of narcissism? What might be some examples of narcissism? What connection does Tom Elemans make to individualism?

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#oembed-4

Ann Morgan: My year reading a book from every country in the world

Ann Morgan considered herself well read — until she discovered the “massive blindspot” on her bookshelf. Amid a multitude of English and American authors, there were very few books from beyond the English-speaking world. So she set an ambitious goal: to read one book from every country in the world over the course of a year. Now she’s urging other Anglophiles to read translated works so that publishers will work harder to bring foreign literary gems back to their shores. Explore interactive maps of her reading journey here: go.ted.com/readtheworld

Check out her blog: A year of reading the world where you can find a complete list of the books I read, and what I learned along the way.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#oembed-5

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/introductiontohumanitiesv2/?p=77#h5p-15

Analysis and Interpretation

Defining literature.

Literature , in its broadest sense, is any written work. Etymologically, the term derives from Latin litaritura/litteratura “writing formed with letters,” although some definitions include spoken or sung texts. More restrictively, it is writing that possesses literary merit. Literature can be classified according to whether it is fiction or non-fiction and whether it is poetry or prose. It can be further distinguished according to major forms such as the novel, short story or drama, and works are often categorized according to historical periods or their adherence to certain aesthetic features or expectations (genre).

Taken to mean only written works, literature was first produced by some of the world’s earliest civilizations—those of Ancient Egypt and Sumeria—as early as the 4th millennium BC; taken to include spoken or sung texts, it originated even earlier, and some of the first written works may have been based on a pre-existing oral tradition. As urban cultures and societies developed, there was a proliferation in the forms of literature. Developments in print technology allowed for literature to be distributed and experienced on an unprecedented scale, which has culminated in the twenty-first century in electronic literature.

Definitions of literature have varied over time. In Western Europe prior to the eighteenth century, literature as a term indicated all books and writing. [1] A more restricted sense of the term emerged during the Romantic period, in which it began to demarcate “imaginative” literature. [2]

Contemporary debates over what constitutes literature can be seen as returning to the older, more inclusive notion of what constitutes literature. Cultural studies, for instance, takes as its subject of analysis both popular and minority genres, in addition to canonical works. [3]

Major Forms

A calligram by Guillaume Apollinaire. These are a type of poem in which the written words are arranged in such a way to produce a visual image.

Poetry is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, prosaic ostensible meaning (ordinary intended meaning). Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its being set in verse; [4] prose is cast in sentences, poetry in lines; the syntax of prose is dictated by meaning, whereas that of poetry is held across metre or the visual aspects of the poem. [5]

Prior to the nineteenth century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines; accordingly, in 1658 a definition of poetry is “any kind of subject consisting of Rythm or Verses”. [6] Possibly as a result of Aristotle’s influence (his Poetics ), “poetry” before the nineteenth century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art. [7] As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition; [8] hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

Prose is a form of language that possesses ordinary syntax and natural speech rather than rhythmic structure; in which regard, along with its measurement in sentences rather than lines, it differs from poetry. [9] On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that ”

- Novel : a long fictional prose narrative.

- Novella :The novella exists between the novel and short story; the publisher Melville House classifies it as “too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story.” [10]

- Short story : a dilemma in defining the “short story” as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative. Apart from its distinct size, various theorists have suggested that the short story has a characteristic subject matter or structure; [11] these discussions often position the form in some relation to the novel. [12]

Drama is literature intended for performance. [13]

- Leitch et al. , The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism , 28 ↵

- Ross, “The Emergence of “Literature”: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century,” 406 & Eagleton, Literary theory: an introduction , 16 ↵

- “POETRY, N.”. OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY . OUP . RETRIEVED 13 FEBRUARY 2014 . (subscription required) ↵

- Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics , 938–9 ↵

- Ross, “The Emergence of “Literature”: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century”, 398 ↵

- FINNEGAN, RUTH H. (1977). ORAL POETRY: ITS NATURE, SIGNIFICANCE, AND SOCIAL CONTEXT. INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS. P. 66. & MAGOUN, JR., FRANCIS P. (1953). “ORAL-FORMULAIC CHARACTER OF ANGLO-SAXON NARRATIVE POETRY”.SPECULUM 28 (3): 446–67. DOI:10.2307/2847021 ↵

- Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics , 938–9 &Alison Booth; Kelly J. Mays. “Glossary: P”. LitWeb, the Norton Introduction to Literature Studyspace . Retrieved 15 February 2014 . ↵

- Antrim, Taylor (2010). “In Praise of Short”. The Daily Beast . Retrieved 15 February 2014 . ↵

- ROHRBERGER, MARY; DAN E. BURNS (1982). “SHORT FICTION AND THE NUMINOUS REALM: ANOTHER ATTEMPT AT DEFINITION”. MODERN FICTION STUDIES . XXVIII (6). & MAY, CHARLES (1995). THE SHORT STORY. THE REALITY OF ARTIFICE . NEW YORK: TWAIN. ↵

- Marie Louise Pratt (1994). Charles May, ed. The Short Story: The Long and the Short of It . Athens: Ohio UP. ↵

- Elam, Kier (1980). The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama . London and New York: Methuen. p. 98.ISBN 0-416-72060-9. ↵

- Literature. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Image of man formed by words. Authored by : Guillaume Apollinaire. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Calligramme.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Privacy Policy

- Strategy: Scholarly Literature

- Definitions

The Literature A body of non-fictional books and writings published on a particular subject; considered collectively. See Oxford English Dictionary, " Literature "

Literature Review A formal, reflective survey of the most significant and relevant works of published and peer-reviewed academic research on a particular topic, summarizing and discussing their findings and methodologies in order to reflect the current state of knowledge in the field and the key questions raised. See Oxford Reference Online, " Literature Review "

Academic Journals A discipline‐specific publication through which academics and other researchers can publish and disseminate their work, the academic journal normally takes the form of a collection of articles, research papers, or reviews which have been submitted to the journal's editorial board. In most cases papers being considered for publication are submitted for scrutiny and appraisal by recognized academics or authorities in the appropriate field, who may recommend that the paper be accepted as it stands, or that specific revisions be made, or that the paper be rejected for publication. This process of refereeing is known as peer review. See Oxford Reference Online, " Academic Journals "

P eer Review The process by which an academic journal passes a paper submitted for publication to independent experts for comments on its suitability and worth; refereeing. See Oxford English Dictionary, " Peer Review "

- Next: Reading a Scholarly Article >>

- Reading a Scholarly Article

Ask a Librarian

- Location of Academic Knowledge Consider what voices are invited to join the scholarly conversation. What voices are excluded or absent?

- Academic Knowledge & Publishers Consider who controls printing & dissemination of academic knowledge? Consider the shift to open access.

- University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Research Guides

- Site: Research Strategies

- Last Updated: Nov 3, 2022 3:21 PM

- URL: https://libguides.colorado.edu/strategy/scholarly

Definition of Literature

What is literature (definition of literature by celebrated authors).

The word ‘ Literature’ is a modified form of a Latin word ( literra, litteratura or litteratus) that means: ‘ writing formed with letters’ . Let us look at what is literature according to definitions by different celebrated literary personalities.

Literature can be any written work, but it is especially an artistic or intellectual work of writing. It is one of the fine arts, like painting, dance, music, etc. which provides aesthetic pleasure to the readers. It differs from other written works by only its one additional trait: that is aesthetic beauty. If a written work lacks aesthetic beauty and serves only utilitarian purpose, it is not literature. The entire genre like poetry, drama, or prose is a blend of intellectual works and has an aesthetic beauty of that work. When there is no any aesthetic beauty in any written work that is not pure literature.

Definition of Literature According to Different Writers

Throughout the history of English literature , many of the great writers have defined it and expressed its meaning in their own way. Here are the few famous definitions of literature by timeless celebrated authors.

Virginia Woolf : Virginia defined literature in a perfect way. “Literature is strewn with the wreckage of those who have minded beyond reason the opinion of others.”

Ezra Pound : “Great literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree.”

Alfred North Whitehead : “It is in literature that the concrete outlook of humanity receives its expression.”

Henry James : “It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature.”

Lewis : “Literature adds to reality, it does not simply describe it. It enriches the necessary competencies that daily life requires and provides; and in this respect, it irrigates the deserts that our lives have already become.”

Oscar Wilde : “Literature always anticipates life. It does not copy it but moulds it to its purpose. The nineteenth century, as we know it, is largely an invention of Balzac.”

Chesterton : “Literature is a luxury; fiction is a necessity.”

Forster: The definition of literature by Forster is much interesting. “What is wonderful about great literature is that it transforms the man who reads it towards the condition of the man who wrote”.

All the these definitions of literature by great writers represent different aspects of it, and shows that in how many ways it can be effective.

Literature: A Depiction of Society

It might sound strange that what is literature’s relation with a society could be. However, literature is an integral part of any society and has a profound effect on ways and thinking of people of that society. Actually, society is the only subject matter of literature. It literally shapes a society and its beliefs. Students, who study literature , grow up to be the future of a country. Hence, it has an impact on a society and it moulds it.

According to different definitions of literature by authors, it literally does the depiction of society; therefore, we call it ‘ mirror of society’ . Writers use it effectively to point out the ill aspects of society that improve them. They also use it to highlight the positive aspects of a society to promote more goodwill in society.

The essays in literature often call out on the problems in a country and suggest solutions for it. Producers make films and write novels, and short stories to touch subjects like morals, mental illnesses, patriotism, etc. Through such writings, they relate all matters to society. Other genre can also present the picture of society. We should keep in mind that the picture illustrated by literature is not always true. Writers can present it to change the society in their own ways.

The Effects of Literature on a Society:

The effects of literature on a society can be both positive and negative. Because of this, the famous philosophers Aristotle and Plato have different opinions about its effect on society.

Plato was the one who started the idea of written dialogue. He was a moralist, and he did not approve of poetry because he deemed it immoral. He considered poetry as based on false ideas whereas the basis of philosophy came from reality and truth. Plato claims that, “poetry inspires undesirable emotions in society. According to him, poetry should be censored from adults and children for fear of lasting detrimental consequences” (Leitch & McGowan). He further explains it by saying, “Children have no ability to know what emotions should be tempered and which should be expressed as certain expressed emotions can have lasting consequences later in life”. He says, “Strong emotions of every kind must be avoided, in fear of them spiraling out of control and creating irreparable damage” (Leitch & McGowan). However, he did not agree with the type of poetry and wanted that to be changed. ( read Plato’s attack on poetry )

Now Aristotle considers literature of all kinds to be an important part of children’s upbringing. Aristotle claims that, “poetry takes us closer to reality. He also mentioned in his writings that it teaches, warns, and shows us the consequences of bad deeds”. He was of the view that it is not necessary that poetry will arouse negative feelings. ( Read Aristotle’s defense of poetry )

Therefore, the relation of literature with society is of utter importance. It might have a few negative impacts, through guided studying which we can avoid. Overall, it is the best way of passing information to the next generation and integral to learning.

Related Articles

History of english literature.

Different types of literature

What is literary English?

Figurative language in English literature

What is a sonnet?

What is metaphysical poetry?

Definition and types of irony

Literary terms used in English drama

How to answer a literary question?

Shakespearean Tragedy

Greek tragedy versus Shakespearean tragedy

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

10 Definitions of Literature According to Experts, Complete Characteristics and Functions

- December 16, 2021

- In Miscellanea

10 Definitions of Literature According to Experts, Complete Characteristics and Functions In Indonesian, there are various types of languages contained in it. The language contained in it can give us the readers a positive value or a negative value.

From language we can get to know more about what happens in social life and socializing. State life is also often discussed in language, because language can unite various tribes and cultures.

list of contents

Definition of Literature

1. mursal esten, 3. panuti sudjiman, 4. ahmad badrun, 5. eagleton, 7. aristotle, 8. robert scholes, characteristics of literature, literary function.

- Share this:

- Related posts:

In Indonesian there is literature which is a form of language. Literature has many meanings contained in it. To know more about literature, it can be explained as follows:

Understanding literature in general is a form of a very beautiful work either written or spoken. For the understanding of the origin of Literature is an absorption word from the Sanskrit language, namely Literature which means "text containing instructions" or Guidelines , the meaning of 'Sas' which means instructions or in the form of teachings and the meaning of 'tra' which has meaning tool or means . In Indonesian, the word is used to refer to literature or a type of writing that has a certain meaning or has a certain beauty.

Literature is divided into two parts, namely prose and poetry. Prose is a literary work that is not bound. Poetry is a literary work that has ties to certain rules or regulations. Examples of prose literature include novels, stories or short stories, and dramas. Examples of poetry literature include Poetry, Pantun, and also Poetry.

Understanding Literature According to Experts

The definition of literature according to experts varies and among them are different. So the definition of literature according to experts will be explained as follows:

Definition of Literature or Literature is the disclosure of artistic and imaginative facts as a manifestation of human life. (and society) through language as a medium and has a positive effect on human life (humanity).

Definition of Literature. is a form and result of creative art work whose object is humans and their lives use language as the medium.

Understanding Literature as an oral or written work that has various superior characteristics such as originality, artistry, beauty in content, and expression.

Understanding Literature is an artistic activity that uses language and lines of other symbols as a tool, and is imaginative.

In his opinion, fine writing (belle letters) is a work that records the form of language. daily in various ways with language that is condensed, deepened, entangled, lengthened, and reversed, made odd.

Understanding Literature is the result of imitation or description of reality (mimesis). A literary work must be an example of the universe as well as a model of reality. Therefore, the value of literature is getting lower and far from the world of ideas.

In his opinion, namely as other activities through religion, science and philosophy.

Understanding literature and Of course, literature is a word, not a thing.

Explain that literature is a social institution that uses language as a medium. Language itself is a social creation. Literature displays a picture of life, and life itself is a social reality.

He argues that literature is a creative work or fiction that is imaginative or "literature is the use of beautiful and useful language that signifies other things"

To be called a literary work, unique characteristics or things are needed that can define that this is literature. These characteristics are:

- The contents can describe humans with various forms of problems.

- There is a good and beautiful language order.

- The way it is presented can give an impression and appeal to the audience.

The functions of literary works vary. These literary functions will be explained as follows:

- reactive is to provide an impression or entertainment for the readers.

- Activated is to be able to provide knowledge or insight about the problems that exist in life to its readers.

- Aesthetic is to give beauty to the readers.

- Morality is to provide moral knowledge between good and bad for the readers.

- Religious is to be able to present the value of religious teachings in it that can be imitated by its readers.

That's the explanation about 10 Definitions of Literature According to Experts, Complete Characteristics and Functions described above. Literature can have a negative impact as well as a negative impact on students

- Definition of Literary Arts, Functions, Characteristics, Benefits, Elements and Types

- Understanding Novels According to Experts and Its Elements (Full Discussion)

- Stylistic Theory in Literary Analysis (Full Discussion)

- Definition of Fiction Stories, Structure, Types, Elements & Language Rules

- Understanding Novel: Characteristics, Structure, Elements and Types of Novels

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of literature

Examples of literature in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'literature.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin litteratura writing, grammar, learning, from litteratus

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

Phrases Containing literature

- gray literature

Articles Related to literature

Famous Novels, Last Lines

Needless to say, spoiler alert.

New Adventures in 'Cli-Fi'

Taking the temperature of a literary genre.

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan...

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan Sees It

We know how the Nobel Prize committee defines literature, but how does the dictionary?

Dictionary Entries Near literature

literature search

Cite this Entry

“Literature.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/literature. Accessed 2 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of literature, more from merriam-webster on literature.

Nglish: Translation of literature for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of literature for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about literature

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 29, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

What is Novel? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Novel definition.

A novel (NAH-vull) is a narrative work of fiction published in book form. Novels are longer than short stories and novellas, with the greater length allowing authors to expand upon the same basic components of all fictional literature—character, conflict , plot , and setting , to name a few.

Novels have a long, rich history, shaped by formal standards, experimentation, and cultural and social influences. Authors use novels to tell detailed stories about the human condition, presented through any number of genres and styles .

The word novel comes from the Italian and Latin novella , meaning “a new story.”

The History of Novels

Ancient Greek, Roman, and Sanskrit narrative works were the earliest forebears of modern novels. These include the Alexander Romances, which fictionalize the life and adventures of Alexander the Great; Aethiopica , an epic romance by Heliodorus of Emesa; The Golden Ass by Augustine of Hippo, chronicling a magician’s journey after he turns himself into a donkey; and Vasavadatta by Subandhu, a Sanskrit love story.

The first written novels tended to be dramatic sagas with valiant characters and noble quests, themes that would continue to be popular into the 20th century. These early novels varied greatly in length, with some consisting of multiple volumes and thousands of pages.

Novels in the Middle Ages

Literary historians generally recognize Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji as the first modern novel, written in 1010. It’s the story of a Japanese emperor and his relationship with a lower-class concubine. Though the original manuscript, consisting of numerous sheets of paper glued together in book-like format, is lost, subsequent generations wrote and passed down the story. Twentieth-century poets and authors have attempted to translate the confusing text, with mixed results.

Chivalric romantic adventures were the novels of choice during the Middle Ages. Authors wrote them in either verse or prose , but by the mid-15th century, prose largely replaced verse as the preferred writing technique in popular novels. Until this time, there wasn’t much distinction between history and fiction; novels blended components of both.

The birth of modern printing techniques in the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in a new market of accessible literature that was both entertaining and informative. As a result, novels evolved into almost exclusively fictional stories to meet this upsurge in demand.

Novels in the Modern Period