- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Staff portal (Inside the department)

- Student portal

- Key links for students

Other users

- Forgot password

Notifications

{{item.title}}, my essentials, ask for help, contact edconnect, directory a to z, how to guides.

- Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation

A review of the effects of early childhood education

This literature review was originally published 06 March 2018.

- 2018 effects of early childhood education summary (PDF 215 KB)

- 2018 effects of early childhood education (PDF 1045 KB)

This literature review summarises evidence of the relationship between early childhood education and cognitive and non- cognitive outcomes for children. It also summarises evidence from a number of international longitudinal studies and randomised control trials. Australian evidence, though limited, has also been summarised .

Main findings

High quality early childhood education can improve children’s cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes.

High-quality early childhood education is robustly associated with positive outcomes at school entry. Children who participate in early childhood education have higher cognitive and non- cognitive development than children who do not participate. The benefits of early childhood education are stronger at higher levels of duration (years) and intensity (hours) of attendance. However, most early childhood education interventions yield short-term outcomes, with effects ‘fading out’ between one to three years after the intervention.

The Australian evidence base on early childhood education effects is relatively limited. The extent to which early childhood education affects Australian children's development is largely unknown.

Disadvantaged children stand to gain the most from high quality early childhood education

High-quality early childhood education is particularly beneficial for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, as early childhood education provides cognitive and non-cognitive stimulation not available in the home learning environment. Interventions are best provided in the earliest years of life, as these yield higher developmental, social, and economic returns than interventions provided at later stages. Early childhood education interventions help to reduce inequalities in educational outcomes for disadvantaged children at the time of school entry.

Small-scale, intensive early childhood education interventions (such as the well-known High/Scope Perry Preschool and Abecedarian programs), that incorporate additional components such as parenting programs and home visits from teachers are found to be most effective. Compared to more universal programs, smaller-scale, intensive interventions produce longer-term outcomes.

The positive effects of early childhood education programs are contingent upon, and proportionate to, their quality

The provision of high-quality early childhood education is beneficial for learning and development. Early childhood education quality typically comprises structural quality (characteristics such as the teacher to child ratio) and process quality (nature of interactions between children; their environment; and teachers and peers). A policy lever that will increase the positive effects of early childhood education participation is an increase in educational quality.

Early childhood education

Recent analysis of early childhood education quality in Australia undertaken by Melbourne University’s E4Kids study, shows that there remains substantial room for quality improvement in Australian jurisdictions, including NSW .

- Literature review

- Teaching and learning practices

Business Unit:

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Game-based learning in early childhood education: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

Select one of your emails

You have multiple emails registered with Frontiers:

Notify me on publication

Please enter your email address:

If you already have an account, please login

You don't have a Frontiers account ? You can register here

Game-based learning has gained popularity in recent years as a tool for enhancing learning outcomes in children. This approach uses games to teach various subjects and skills, promoting engagement, motivation, and fun. In early childhood education, game-based learning has the potential to promote cognitive, social, and emotional development. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to summarize the existing literature on the effectiveness of game-based learning in early childhood education This systematic review and meta-analysis examine the effectiveness of game-based learning in early childhood education. The results show that game-based learning has a moderate to large effect on cognitive, social, emotional, motivation, and engagement outcomes. The findings suggest that game-based learning can be a promising tool for early childhood educators to promote children's learning and development. However, further research is needed to address the remaining gaps in the literature. The study's findings have implications for educators, policymakers, and game developers who aim to promote positive child development and enhance learning outcomes in early childhood education.

Keywords: game-based learning, Early Childhood, cognitive outcomes, social engagement, Emotional Development

Received: 05 Oct 2023; Accepted: 20 Mar 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Alotaibi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Manar Alotaibi, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Education - Early Childhood Education

- Kindergarten

- Mathematics

- Physical education

- Social Studies

- English language learners

- Learning environments

- Outdoor education

- Play-based learning

- Language arts

- Picture books for science

- Picture books for math

- Picture books without words

- Picture books in rhyme

- Picture books in song

- Picture Books in French

- Picture books - for character education

- Picture books about writing

- Alphabet books

- Early readers

- Pia's Picks

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Journal Browsing

- Journal Article & Database Searching

- Books & Catalogue Searching

- Research Books by Topic

- Help Videos

- Citation Help

- Literature Reviews

- Projects, Theses & Dissertations

- Related Library Guides

- Literature reviews

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Projects, Theses & Dissertations

Search Tools

Library Search - Search all UVic resources

Search for Books and eBooks

What is a literature review?

You can find many help videos on how to do a literature review available through youtube. This one by North Carolina State University is particularly good.

You have likely heard your instructors or supervisors using the following terms. So that you know the difference between each concept, consider the following definitions taken from ODLIS: The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science (2013), edited by Librarian Joan Reitz at Western Conneticut State University.

Literature Review: "A comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, criticalbibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works." ( The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science )

Literature Search: "An exhaustive search for published information on a subject conducted systematically using all available bibliographic finding tools, aimed at locating as much existing material on the topic as possible, an important initial step in any serious research project." ( The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science )

Systematic Review: "A literature review focused on a specific research question, which uses explicit methods to minimize bias in the identification, appraisal, selection, and synthesis of all the high-quality evidence pertinent to the question. Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials are so important to evidence-based medicine that an understanding of them is mandatory for professionals involved in biomedical research and health care delivery. Although many biomedical and healthcare journals publish systematic reviews, one of the best-known sources is The Cochrane Collaboration, a group of over 15,000 volunteer specialists who systematically review randomized trials of the effects of treatments and other research." ( The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science )

Bibliography: "Strictly speaking, a systematic list or enumeration of written works by a specific author or on a given subject, or that share one or more common characteristics (language, form, period, place of publication, etc.). When a bibliography is about a person, the subject is the bibliographee. A bibliography may be comprehensive orselective. Long bibliographies may be published serially or in book form...In the context of scholarly publication, a list of references to sources cited in the text of an article or book, or suggested by the author for further reading, usually appearing at the end of the work. Style manuals describing citation format for the various disciplines (APA, MLA, etc.) are available." ( The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Scienc e)

Annotated Bibliography: "A bibliography in which a brief explanatory or evaluative note is added to each reference or citation. An annotation can be helpful to the researcher in evaluating whether the source is relevant to a given topic or line of inquiry." (The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science)

Critical Annotation: "In a bibliography or list of references, an annotation that includes a brief evaluation of the source cited, as opposed to one in which the content of the work is described, explained, or summarized." (The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science)

Citation: "In the literary sense, any written or spoken reference to an authority or precedent or to the verbatim words of another speaker or writer. In library usage, a written reference to a specific work or portion of a work (book, article, dissertation, report, musical composition, etc.) produced by a particular author, editor, composer, etc., clearly identifying the document in which the work is to be found. The frequency with which a work is cited is sometimes considered a measure of its importance in theliterature of the field. Citation format varies from one field of study to another but includes at a minimum author, title, and publication date. An incomplete citation can make a source difficult, if not impossible, to locate." ( The Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science ).

- << Previous: Citation Help

- Next: Projects, Theses & Dissertations >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uvic.ca/earlychildhood

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A Review on Early Intervention Systems

Kristen tollan.

1 Department of Communication and Culture, York University, Toronto, ON M3J 1P3 Canada

2 School of Early Childhood Studies, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON M5B 2K3 Canada

Rita Jezrawi

3 Offord Centre for Child Studies, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L8 Canada

Kathryn Underwood

Magdalena janus, associated data.

Not applicable.

Purpose of Review

Early intervention programs have been shown to increase the overall socio-emotional and physical wellbeing of children in early childhood and educational settings. The goal of this narrative review is to explore recent literature that describes implementation of these systems and highlights innovative practices in the early childhood intervention sector.

Recent Findings

Twenty-three articles were included, and we identified three themes in this review. The literature addressed concepts of innovative techniques in relation to childhood disability interventions; policy practices that promote child, family, and practitioner wellbeing; and attention to the importance of trauma-informed care in education for children and families who face the impacts of social marginalization such as racism and colonization.

Notable shifts in the current early intervention paradigms are approaches to understanding disability informed by intersectional and critical theories, as well as systems level thinking that goes beyond focusing on individual intervention by influencing policy to advance innovative practice in the sector.

Introduction

The early years of life are crucial for setting the foundation for healthy child development. The benefits of early interventions on the health of disabled children with intellectual and developmental disabilities have been well established albeit with varying levels of evidence of effectiveness [ 1 – 5 ]. Health and education service sectors have focused efforts on early identification, screening, prevention models, and early treatment options for disabled children. However, there is little research on the social conditions and contexts within which children and families access early intervention services.

Current debates in the field include the evidence-based ability to assess effectiveness and usefulness of different types of early interventions. Existing evidence is based mostly on North American data; yet despite the Western focus, differences within countries with provincial or state-governed health and education systems are apparent and result in discrepancies in availability, access, and effectiveness of early interventions. For instance, variability in funding, delivery, and design of services is evident within and between jurisdictions; policy decisions are made for private versus public funding, direct versus indirect financial support, and whether services will be integrated and delivered in school or clinical settings [ 6 ]. Population level data are also critical in tracking the social determinants of health such as family, socioeconomic, and geographic characteristics that contribute to the success and experience in early interventions. Population-level monitoring may also inform strategies to mediate the impacts of racism, colonialism, and other inequities that influence child health. As early interventions continue to be a key preventive and mitigation strategy in early childhood special education and healthcare, it is crucial that policymakers and professionals address the causes of bias and racism within systems and further promote wellness and equity [ 7 •]. Best practices, such as collaboration and partnerships between families and professionals, as well as family-centred and strengths-based approaches in the face of the diverse and complex needs of individual families and limited resources are best candidates for optimal service delivery [ 8 ]. The purpose of this narrative review was to synthesize emerging evidence and recent research on interventions in early childhood and identify avenues for improvement in the field.

Methodology

We conducted a narrative review of English-language peer-reviewed research articles describing or evaluating education-focused early interventions for children with developmental and intellectual disabilities from 2018 to 2022.

Prior to the review, an initial scan of recent literature was conducted by one of the authors (KT), and we identified three main topic areas that were discussed frequently in the articles (social model, policy, and trauma-informed care). We then conducted the review using the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) database through three searches based on the topic areas we identified. Search terms in strings of various combinations were used and interchanged with synonymous and related terms. Sample search terms for the topic areas included the following: early childhood education, early intervention, innovation, policy, policy evaluation, public health, service delivery, early intervention policy, developmental disability, intellectual disability, special needs, child, family, and trauma. In the first search, the focus was on early childhood education for children who have dealt with traumatic experiences. The second search focused on childhood disability and interventions for young children with disabilities. Educational policy and the development of interventions systems for early childhood settings was the focus of the third search. Additional relevant articles were identified through reference list checking, personal libraries, and additional searches on Google Scholar, ProQuest, and PubMed databases. After extracting the titles and eliminating duplicates, articles were screened by title and abstract for relevance and applicability to the main research questions. We included articles that specifically focused on early childhood education settings, services, and interventions, rather than medical or paediatric settings. The articles for potential inclusion in the review were also assessed in full-text for relevance by two of the authors (KT & RJ), and the main details of each article were extracted in a spreadsheet. We did not assess the quality or conduct pooled analysis of the articles, because our interest was in the current discourses in the field of early intervention. Of the 468 unique articles located, 71 received the full text review by two authors (KT & RJ), and 23 were included in the final review.

Findings and Discussion

As indicated above, we identified three main themes in recent work related to early childhood intervention systems in the selected literature through preliminary search. The first theme addressed the outcomes of disabled children in early intervention settings, as well as the mitigation of impairment, and social approaches to understanding childhood disability. The second theme was centre-based policies and programs in early intervention. The third theme was trauma-informed practice. The research on childhood trauma was not limited to a particular type of trauma, but rather reflects the influence of social factors such as racism, economic difficulties, and colonization on the trajectory of children exposed to these issues early on in their lives. We discuss each of these themes in greater detail below.

Intersectional Approaches to Disability and Early Intervention

Early intervention systems are commonly accessed by and aim to serve disabled children and their families. Much of the research in this area focuses on mitigating sub-optimal outcomes of childhood disability and testing individual interventions in early childhood education and care. However, more recent literature on this topic recognizes disability as a complex categorization of children that includes both the impact of individual impairments and the influence of societal barriers [ 10 •]. Theoretical models of disability are rapidly changing how we think about early intervention. Disabled Children’s Childhood Studies as a field is informed by an understanding that childhood both influences later outcomes and is a time for important experiences in the present. Further, this field critiques the focus of early intervention on rehabilitation, finding additional value in the diversity of characteristics in childhood [ 10 •, 11 , 12 •].

For example, Guralnick proposes a developmental system approach to all early childhood education and care programs that values inclusive practice and individualized goals for both children and their families [ 9 •]. This is a more traditional discourse for understanding early childhood intervention; however, when Guralnick first proposed their developmental systems approach, it was quite innovative for the time. This approach presented an opportunity to link sociological perspectives to intervention policy, as well as seeing the child as a part of a broader, interactive system rather than just a need for intervention. In this approach, Guralnick identifies three key principles for inclusive early childhood systems: relationships, comprehensiveness, and continuity in interactions with families and children [ 9 •].

Critical Approaches to Understanding Childhood

Park and colleagues turn away from the medical model of understanding disability and not only use a social model of disability for their framework, but they use a “DisCrit” theory to analyse their data, recognizing that race is a critical factor in understanding disability experiences [ 13 •]. DisCrit studies combine critical disability studies and critical race theory and recognize the interconnection between ableism, racism, and other forms of discrimination, calling for a shift to affirming recognition of the place of disabled children in society, particularly disabled children of colour [ 14 , 15 ]. Using video footage of one early childhood classroom, Park and colleagues identified the “humanizing” approaches to teaching disabled students. In this classroom, educators reimagined assistance for children through giving time and space and assisting and centring the child [ 13 •]. The educators allowed students to transition from activities on their own time and in the manner they desired, which promoted independence and individuality and also advanced justice for the children of colour by allowing them to be themselves, rather than who the adults wanted them to be. The authors of this study also applied DisCrit to their analysis in early educational settings. They noted that a culture of surveillance is often experienced in special educational settings by children of colour with disabilities in which they are asked to behave in certain ways and monitored for adherence to those requests [ 13 •]. The educators in this classroom ultimately emphasized shifts from the typical special education classroom: from surveillance to responsiveness and from a deficit view of students to a humanizing one.

Boone and colleagues similarly examine systemic racism in early intervention, advocating for the implementation of equity-informed intervention systems in early childhood [ 7 •]. They believe that acknowledging social stratifications and centring children of colour is critical in advancing equity in these systems, something they term “ally-designed” in contrast to a typical “saviour-designed” approach. In line with many recent calls, the authors argue that it is the systems that need to be reformed in order to achieve a change that will result in sustainable, equitable access and quality of early intervention for all children who need it.

Love uses the framework of heterotopias, originally coined by Foucault, to describe early childhood education and care where the real and the unreal are colliding in the same space [ 16 •]. Love sees this as a divide between the physical existence of the children, teachers, and their classroom materials and the socially constructed interpretations of developmental norms, differences, and the overall understanding of the function of the classroom and the school environment. Furthermore, Love argues that early childhood administrators serve as the “architects'' of these heterotopias, as they are responsible for the implementation of inclusive practices in their centres [ 16 •]. The placement of a disabled child within a “general education” classroom does not necessarily ensure inclusive practices that support the needs of the child, in what is called the “façade of inclusion.” She argues that inclusion that is defined by placement alone promotes a binary understanding of children as disabled or not disabled, a concept predicated on “typical” development that does not address the effects of intersectionality discussed later in this paper [ 16 •]. Furthermore, Love believes that “categorizing children based on whether they have an identified disability or not obscures nuances of both children and their developmental context, which can undermine efforts to be responsive to their multiple identities and strengths” (p. 140) [ 16 •]. Love states that place-based inclusion forces the child into a box dictating that they be ready to perform in certain ways and adhere to certain practices expected of a “typically developing” child, whereas her framework of heterotopies suggests that schools must be prepared and ready to include all students, promoting the value of and response to children’s diverse needs and abilities. Ultimately, she argues that to achieve this expansive conceptualization of inclusive education, children of all backgrounds must be included, not just disabled children, but that inclusiveness must also consider socioeconomic status, race, and language.

Early Intervention Policies and Programs

Policies and programs for disabled children are often predicated on early intervention approaches that require the support of multi-sectoral services and funding in order to conduct early identification of disorders and ease the transition between services and supports across the various sectors involved in care. The early learning and early intervention systems have a high degree of variability in the scope and range of services that are provided to families because of a lack of legislation or guidelines to ensure services are implemented, utilized, and evaluated [ 6 ]. However, jurisdictions may consider curating their early intervention services with key aspects of high-quality early intervention systems: early identification and screenings; easy transitions between early childhood clinical, educational, and therapeutic programs; and a high degree of family/educator involvement.

Early identification

The identification of a disorder through developmental screening programs is often a precursor to accessing early intervention, but socioeconomic inequalities between groups may affect the availability and utilization of diagnostic services. In the USA, Sheldrick and colleagues investigated the use of a multistage autism screening protocol in early intervention sites to mitigate the impact of socioeconomic status, racial or ethnic minority status, and non-English speaking status on autism screening [ 17 •]. The authors found that multistage screening protocols are associated with an increased diagnosis of autism particularly for Spanish-speaking families who traditionally have lower incidence rates [ 17 •]. Placing greater importance on collaborative clinician and parent-decision making in the case of multistage assessments can improve early intervention service utilization and create opportunities for families to access services requiring an official diagnosis.

Transitions

Transitions between early childhood education and care, and school-based services are prevalent in the literature. In a meta-synthesis of 196 caregiver experiences, Douglas, Meadan, and Schultheiss explored transitions from home- and childcare-based early intervention to early childhood special education programs. They identified interagency infrastructure and policies and alignment and continuity of service delivery as critical to communication between caregivers, service coordinators, and teachers in early childhood special education programs [ 17 •]. The transitions from early interventions delivered in home or childcare settings to specialized early childhood education and care programs within the preschool systems were described by Douglas and colleagues as difficult for families [ 18 •]. Similarly, families describe poor communication between educators and therapists as they transition from the early years into school and lower perceptions of quality of care [ 19 , 20 •]. Several studies identify a lack of interest or formal procedure for school-based staff to learn from early years’ programs and services in developing programs for disabled children. Further, a lack of resources allocated to transition processes has been identified, and families can face further gatekeeping from services that are only accessible for specific diagnoses [ 20 •, 21 ]. The presence of guidelines for transition teams who can regularly meet with parents and educators to provide teaching strategies, therapeutic equipment, or logistical planning improves the transition process and level of support from early years to kindergarten [ 21 ].

Several studies examined the structure of early childhood and early intervention services with the goal to enhance coordination and create access to support. Hemmeter et al. evaluated a pyramid model that provides targeted developmental support through program-wide support [ 22 •]. Despite concerns with attrition rates of children and classrooms, program-wide support such as training and coaching teachers on this model was shown to create positive classroom and individual outcomes for children, particularly for managing challenging behaviour and enhancing social skills [ 22 •]. Similar data-guided approaches incorporate external feedback using validated indicators and summaries of socio-emotional development of children to inform educators [ 23 •]. Preschool educators can then identify children at risk and modify teaching strategies to improve their self-regulation, relationships, and behaviours [ 23 •].Transition teams also need a variety of skilled specialists to coordinate interventions and liaise with families and school providers. Children accessing early intervention services are often described as having complex needs that require staff-intensive collaboration to deliver applied behaviour analysis treatment approaches. In our research, we note that it may be the service system that is complex. Hagopian and colleagues described a neurobehavioural continuum of care program to treat co-occurring conditions and behaviours through an interdisciplinary model that involves behaviour therapists and education coordinators who manage education delivery from the child’s home school [ 26 •]. The continuum of care comprised an outpatient program, an intensive outpatient program, and inpatient neurobehavioral unit, as well as follow-up, medication, and consultation services [ 26 •]. Data gathered from two decades of the program found function-based behavioural interventions reduced target problem behaviour (e.g. aggression, self-injury), and caregivers were well trained to deliver this outpatient treatment in most cases [ 26 •]. However, effectiveness of behavioural intervention programs can be controversial as there are concerns about the quality of research on which they are based [ 27 •]. An important example of a shift in addressing such issues in behavioural interventions, also reflected in the literature, is the inclusion of autistic people on research teams, and the recognition of concerns raised by autistic people themselves about the ethics of behavioural intervention [ 28 •].

Future Directions

Service agencies, providers, and policymakers had to pivot their regular services during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Telehealth emerged as a response to early intervention service disruptions during the pandemic and could be a valuable addition to regular programming for some families, with the proper training and technological resources. Telehealth is also a critical mechanism for access to early intervention and other health services in rural and remote communities as well as in the face of staffing shortages or disruptions [ 24 ]. Barring caregiver resistance or limitations with technology, telehealth offers a high degree of caregiver participation which may result in greater feelings of caregiver empowerment and confidence with implementing strategies posed by early intervention providers [ 25 •]. However, it is not clear how effective telehealth is for direct engagement with children as most providers report working primarily with caregivers to coach them on interventional strategies [ 25 •]. Further, there is a need for more research on the equity implications and relational limitations of these services.

For policymakers and families alike, there may be some challenges in choosing which interventions to fund or purchase that would provide the most return on investment in terms of improved developmental outcomes. One future direction for policies could incorporate a host of early interventions into one overarching program. The cumulative effects of participating in more than one type of early intervention was studied by Molloy and colleagues [ 29 •]. Data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children were used to compare the combined effects of five early interventions—antenatal care, home visiting, preschool, parenting programs, and early years of school. The increase in total service use and participation from birth to 5 years old was associated with better reading scores at 8 and 9 years old [ 29 •]. In contrast, a cumulative risk score from 0 to 5 years old accounted for exposure to risk indicators across all five services; results showed that these indicators were associated with lower reading skills and included inadequate/lack of service use, inadequate resources within programs, and differences in parenting behaviours and communication styles [ 29 •].

Mental Health and Trauma-Informed Care in Early Intervention

Many researchers address the reality that children who experience trauma at an early age are more likely to have access to educational settings than dedicated mental health supports, and as such, it is important to have resources to deal with trauma in educational environments. Recent literature indicates that nearly 1 in 4 preschool children have been exposed to a traumatic event at least once, yet only 2.5% of these children have access to professional mental health care [ 30 , 31 •]. Schools and educational settings are becoming the first point of intervention for trauma-exposed children, while research shows that teachers need further training on dealing with trauma and children who have experienced trauma in these settings.

Educational Settings as Points of Intervention

Bartlett and Smith state that the needs of trauma-exposed preschoolers are often overlooked due to misconceptions about their memory and the belief that they will recover from trauma easily [ 31 •]. While the literature demonstrates a solid understanding that most children do not have sufficient access to mental health support, there is also notable progress towards early childhood education and care programs becoming the first point of intervention. Loomis explored the recent literature as evidence for the importance of implementing early childhood trauma interventions in education and care settings [ 30 ]. Loomis suggests creating consistent trauma-informed environments across early childhood education and care organizations and services, as well as ongoing workplace development and support for staff, psychoeducational support between educators and families, and support for teachers’ mental health.

Training Teachers to Deal with Trauma

Limited research presently exists on the impact of training about trauma for teachers and education staff and whether this contributes to overall well-being within early childhood settings. Loomis and Felt identify the foundations of successful trauma-informed practices, noting the relationship between trauma-informed training content, trauma-informed attitudes, and overall stress in their sample of 111 preschool staff [ 32 •]. They found that those educators who received further training on trauma-informed skills and also had opportunities for self-reflection had stronger, more effective, trauma-informed attitudes than those with only knowledge-based training and no reflection. Similarly, Bartlett and Smith identified a need for further education around trauma-informed practices in early childhood education, stating that it is essential to understand the current landscape of trauma interventions in early childhood education, alongside the impacts of trauma and support needed for children exposed to such events [ 31 •]. They posit that trauma-exposed children often exhibit behaviours that can create greater stress for educators and suggest that educators play a critical role in helping children heal from trauma by ensuring that they have a routine, safe, respectful, and welcoming school environment [ 31 •]. However, they also note that few trauma-informed education-based interventions have been thoroughly studied. There are many current literature reviews on the influence and importance of trauma-informed practices, but our search found few recent articles that investigated these approaches further.

Every child’s experience must include access to diverse learning opportunities, meaningful interactions with peers, and development of a sense of belonging; and yet for many, it also needs to include individualized supports. To ensure optimal experiences for all children, administrators should be aware of both historical and contemporary inequities in education and support the ongoing reflection on and promotion of equitable practices that include and accommodate diverse experiences of children and their families in early childhood environments [ 13 •, 16 •]. Some of the articles included in this review reflect a shift to encompassing the influence of socially stratifying factors and marginalization as part of the experiences addressed by trauma-informed educational practices. By acknowledging that disability is a major factor in shaping people’s experiences and worldviews that can further marginalize those with different abilities, such practices are aligned with the modern social models of disability described in our review. While we admit the limitation of the existing research evidence, we also are optimistic that the near future will bring more actionable evidence that could be used to provide effective, equitable, and successful early intervention experiences for children and their families.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors contributed comments and edits to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Code availability, declarations.

The authors declare no competing interests.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kristen Tollan, Email: ac.ukroy@nallotk .

Rita Jezrawi, Email: ac.retsamcm@riwarzej .

Kathryn Underwood, Email: ac.nosreyr@doowrednuk .

Magdalena Janus, Email: ac.retsamcm@msunaj .

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Advertisement

Active Student Participation in Whole-School Interventions in Secondary School. A Systematic Literature Review

- REVIEW ARTICLE

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2023

- Volume 35 , article number 52 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sara Berti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5238-1077 1 ,

- Valentina Grazia 1 &

- Luisa Molinari 1

4316 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review presents a reasoned synthesis of whole-school interventions seeking to improve the overall school environment by fostering active student participation (ASP) in school activities and decision-making processes. The aims are to describe the selected programs, assess their methodological quality, and analyze the activities soliciting ASP. Among the 205 publications initially provided by the literature search in the academic databases PsycINFO and Education Research Complete, 22 reports met the inclusion criteria of presenting whole-school interventions that solicit ASP in secondary schools, and were thus included in the review. Such publications referred to 13 different whole-school programs, whose implemented activities were distinguished on a 5-point scale of ASP levels, ranging from Very high ASP , when students were involved in a decision-making role, to Very low ASP , when students were the passive recipients of content provided by adults. This review contributes to the literature by proposing an organizing structure based on different levels of ASP, which provides clarity and a common ground for future studies on student participation. Overall, the in-depth description of activities offers a framework to researchers and practitioners for planning interventions aimed at improving the learning environment and contributing meaningfully to the far-reaching goal of encouraging student participation in school life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Play-Based Learning: Evidence-Based Research to Improve Children’s Learning Experiences in the Kindergarten Classroom

Meaghan Elizabeth Taylor & Wanda Boyer

The Role of School in Adolescents’ Identity Development. A Literature Review

Monique Verhoeven, Astrid M. G. Poorthuis & Monique Volman

Wellbeing in schools: what do students tell us?

Mary Ann Powell, Anne Graham, … Nadine Elizabeth White

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research in educational psychology is consistent in showing that the quality of the school environment largely affects student well-being. Indeed, students’ experiences of a supportive school context have a significant impact on positive behaviors, such as academic achievement (Brand et al., 2008 ; Hoy, 2012 ) and good relationships among students and between students and staff (Cohen et al., 2009 ; Thapa et al., 2013 ). Conversely, the poor quality of the learning environment predicts negative outcomes, such as substance use (Weatherson et al., 2018 ) or bullying (Låftman et al., 2017 ).

In view of this, schools need to face the challenge of implementing interventions aimed at changing and improving the learning environment in the direction of promoting positive behaviors and reducing negative outcomes. One of the most promising directions in this regard is based on the adoption of whole-school approaches whose key features are the focus on overall school systems instead of on specific problems (Bonell et al., 2018 ).

The literature on whole-school interventions is broad (see, for example, Charlton et al., 2021 , for an extensive review on whole-school interventions focused on school climate), but it suffers from two major gaps. First, it relies primarily on programs applicable to elementary schools, while studies on high school populations are rarer, presumably because of the multiple challenges derived from the implementation of programs in such complex contexts (Estrapala et al., 2021 ; Vancel et al., 2016 ). Second, despite the importance generally attributed to the active involvement of students in the programs, to our knowledge, no previous reviews have specifically investigated the degree and the characteristics of student participation in such interventions. To address these limitations, in this article, we present a systematic literature review on whole-school interventions carried out in secondary schools and based on programs that envisage students’ active participation and involvement.

Whole-School Interventions for Improving the Learning Environment

In educational research, some reviews and meta-analyses (Charlton et al., 2021 ; Merrell et al., 2008 ; Voight & Nation, 2016 ) have critically synthesized and discussed studies on school interventions aimed at improving the learning environment. These programs have considered different outcomes of improvement, ranging from a general focus on school climate dimensions—e.g., relational aspects, institutional organization, and safety—to more specific aspects, such as bullying, violence, or substance use. However, the degree of effectiveness of such programs remains controversial. For example, a meta-analysis by Ttofi et al. ( 2008 ) indicated that school-based bullying prevention programs were able to bring about positive results, while another meta-analysis on the same topic (Merrel et al., 2008 ) concluded that evidence in this direction was only modest.

More positive results concerning the effectiveness of interventions were reported by Allen ( 2010 ) with reference to programs conducted by means of a whole-school approach. In her literature overview of studies designed to reduce bullying and victimization, the author concluded that whole-school interventions generally showed at least marginal evidence of improvement. Despite these encouraging findings, the studies conducted with a whole-school approach in secondary education contexts were rare. Among these, a well-established framework of whole-school interventions mostly implemented in middle schools is the School-Wide Positive Behavior Support program (for reviews, see Gage et al., 2018 ; Noltemeyer et al., 2019 ), which is a multi-tiered framework engaging students, school staff, and families for the delivery of evidence-based behavioral support aligned to students’ needs (Horner et al., 2004 ). By and large, the study results in this framework are again promising in suggesting a connection between such programs and school improvement, although the evidence is generally moderate and only regards a few of the considered outcome measures.

The mixed or weak results reported in the cited reviews solicit further exploration of the specific characteristics of whole-school interventions. In particular, a major limitation of the literature is the lack of an in-depth analysis of the types of activities proposed to students in each program, especially as far as their direct involvement is concerned. Given the importance attributed to student engagement in school life (Markham & Aveyard, 2003 ), this is a relevant area of inquiry that can inform researchers and practitioners willing to design and conduct whole-school interventions calling for students’ involvement.

Student Involvement in School Intervention

The importance of students’ involvement and participation finds a theoretical ground in the self-determination theory (see Ryan & Deci, 2017 ), according to which people who are self-determined perceive themselves as causal agents in life experiences, being proactive and engaged in the social environment. Studies examining such human disposition in adolescence supported the relevance of self-determination for quality of life and identity development (Griffin et al., 2017 ; Nota et al., 2011 ) and as a full mediator in the negative association between stress and school engagement (Raufelder et al., 2014 ).

In the light of these assumptions, educational and school psychologists have launched scientific and professional debates on the ways in which schools can implement favorable conditions for students to feel active and co-responsible for their educational and academic pathways (Carpenter & Pease, 2013 ; Helker & Wosnitza, 2016 ; Schweisfurth, 2015 ). These debates have reached consensus across-the-board on the recognition that school change and improvement are best fostered by intervention programs in which students are offered opportunities to get actively involved in school life (Baeten et al., 2016 ; Voight & Nation, 2016 ). For this goal to be achieved, all educational agencies are called upon to promote interventions capable of supporting activities that require student involvement and participation (Antoniou & Kyriakides, 2013 ).

The importance of students’ active participation in the school environment has also been confirmed by a substantial amount of literature investigating over time the association between high student involvement and positive learning environments. Mitchell ( 1967 ) reported that school climate is related to the extent of student participation and interaction during school life. Epstein and McPartland ( 1976 ) showed that student opportunities for school involvement were related to satisfactory outcomes. In a 1982 review published, Anderson claimed that “the type and extent of student interaction that is possible within a school appears to be a significant climate variable” (Anderson, 1982 ; p.401). A few years later, Power et al. ( 1989 ) described a program implemented in several contexts and characterized by high student involvement, whose results showed that a high rate of student participation led to their capacity to take on responsibility for building an effective learning environment and positive climate. More recent studies (Vieno et al., 2005 ) have confirmed that democratic school practices, such as student participation in decision-making processes, play a significant role in the development of a sense of community at individual, class, and school levels. The review by Thapa et al. ( 2013 ) confirmed the importance of student classroom participation as a variable affecting school climate and academic achievement.

On these theoretical and empirical grounds, providing space to student voices in decision-making and school change emerges as a powerful strategy for improving school environments and enforcing the success of programs (Mitra, 2004 ). The construct of student agency fits in well with this approach, as it refers to the students’ willingness and skill to act upon activities and circumstances in their school lives (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, 2011 ). Representing adolescents’ authentic, proactive, and transformative contributions to school life (Grazia et al., 2021 ), agency is fostered by school environments capable of soliciting and valorizing students’ active participation in educational practices and school decisions (Makitalo, 2016 ) and encouraging them to feel co-responsible with teachers and staff for their school lives (Mameli et al., 2019 ). The value of agency has been confirmed by research showing its positive associations with motivation and the fulfilment of basic psychological needs (Jang et al., 2012 ) as well as with the perception of supportive teaching (Matos et al., 2018 ).

Despite the agreement on student participation as a crucial feature for the success of programs capable of improving students’ school life, to our knowledge, previous literature reviews on school interventions have not focused specifically on the extent and way in which students are given a voice and are involved in the programs. In view of this, in the present work, we set out to search, in the existing literature, for interventions specifically based on activities in which students were not just the recipients of activities but rather took on an active and decision-making role. For our purposes, we use the notion of active student participation (ASP) to include the variety of ways in which students are given the opportunity to participate actively in school activities and decisions that will shape their own lives and those of their peers.

Review’s Aims

Previous reviews (Charlton et al., 2021 ; Estrapala et al., 2021 ; Voight & Nation, 2016 ) have provided extensive descriptions of whole-school interventions aimed at improving school environments or reducing school problems, suggesting their effectiveness. Moreover, a growing amount of literature has found that students’ active involvement in their school life is a crucial feature for improvement. Our general goal was to move forward by conducting an in-depth examination of existing whole-school interventions based on activities promoting ASP in secondary schools, by providing a reasoned synthesis of their characteristics and implementation. The choice to focus on secondary schools was driven by the evidence that this developmental stage has so far received less attention in whole-school intervention research (Estrapala et al., 2021 ; Vancel et al., 2016 ).

Given the large heterogeneity of existing intervention programs, both in terms of participants (specific subgroups vs general student population) and targets of improvement (specific abilities vs general school environment), it was essential to set clear boundaries for the study selection. As this was a novel undertaking, we chose to focus on whole-school interventions directed to the overall student population and aimed at improving the school climate as a whole. This allowed us to select a reasonably homogeneous sample of studies, with the confidence that future reviews will advance our knowledge by considering more specific fields and populations.

The review’s aims were (a) to describe the selected programs on the basis of their focus, country, duration, age of participants, and research design; (b) to assess the soundness of the research design and methodologies adopted in each study in order to provide evidence of the methodological quality of the selected programs; and (c) to differentiate among various levels of ASP in the program’s activities and, for each of these levels, to describe methods and activities carried out in the programs.

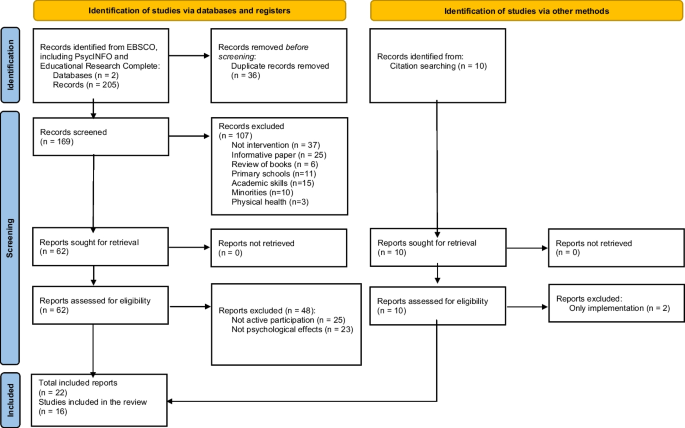

The present review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 updated statement (PRISMA 2020; Page et al., 2021 ). In line with the terminology proposed by the authors, in the following sections, we use the term study for every investigation that includes a well-defined group of participants and one or more interventions and outcomes, report for every document supplying information about a particular study (a single study might have multiple reports), and record for the title and/or abstract of a report indexed in a database. In addition, for the specific purposes of the present review, we use the term program when referring to an implemented whole-school intervention that has specific characteristics and is usually named, since more than one study may be conducted with the same program.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they were (i) written in English language; (ii) published in peer-reviewed academic journals; and (iii) aimed at assessing psychological effects of whole-school interventions that solicit ASP in secondary schools; thus, studies in which students were involved solely as recipients of activities delivered by adults were excluded. Moreover, in line with the review’s aims described above, studies were excluded from the review if they were (i) focused on specific subgroups of students (e.g., ethnical minorities or LGBTQ students); (ii) solely aimed at improving specific skills (e.g., literacy or mathematics); and (iii) solely focused on physical health (e.g., nutrition or physical activity).

Information Sources and Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted via EBSCO, including the academic databases PsycINFO and Education Research Complete, last consulted on April 9, 2022. The entered search terms were school-wide interventions OR whole-school interventions OR school-wide programs OR whole-school programs OR school-wide trainings OR whole-school trainings AND secondary school OR high school OR secondary education. By means of the software’s automated procedure, we searched these terms in the abstracts and filtered the results according to the first two inclusion criteria, selecting articles in English and published in peer-reviewed academic journals.

Selection and Data Collection Process

The records of each study were screened by two researchers, and the potentially relevant studies were further assessed for eligibility by three researchers, who read the full text independently. Moreover, some records relevant to the purposes of the research were identified through the references of the included documents ( forward snowballing ; Wohlin, 2014 ). Data from each included report were searched by two researchers, who worked independently to extrapolate the information relevant to the review, which were (a) the study characteristics; (b) the indicators of methodological quality; and (c) the program activities.

Detailed information about the selection process is provided in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ). The literature search provided 205 total records, and reduced to 169 after the automatic deduplication provided by EBSCO. After the application of our inclusion and exclusion criteria, 62 records were selected for full text reading. Of the 107 excluded records, 37 did not report interventions (e.g., they presented only school surveys), 25 were informative papers on initiatives and/or interventions without assessments, 15 focused only on academic skills attainment, 11 referred to primary schools, 10 focused on minorities, 6 were reviews of books or DVDs, and 3 only evaluated physical health as an outcome. After the full text reading of the 62 selected reports, 48 were excluded as they only discussed aspects related to implementation (e.g., feasibility or fidelity) without assessing the psychological effects of the intervention on students ( n = 23) or did not solicit ASP during the intervention ( n = 25). Thus, 14 reports were included in the sample. In addition, 10 reports were identified by sifting through the references of the selected documents ( forward snowballing ; Wohlin, 2014 ). After the full text reading, two of them were excluded as they did not assess the effects of the intervention. At the end of the selection process, the final sample of the present review included 22 reports, which referred to 16 studies and 13 programs.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study Characteristics

The main information about each study is reported in Table 1 . As for the focus of the interventions, three macro-areas were identified: (a) prevention of violence (nine studies and twelve reports), including programs for less bullying, cyberbullying, dating violence, sexual violence, and aggression; (b) promotion of mental health (five studies and seven reports), including programs for addressing depression and suicide risk and for promoting general psychological health; (c) promotion of positive emotional and relational school climate (two studies and three reports), including programs for enhancing school connectedness and school climate.

Within each macro-area, in Table 1 , the programs are listed following the alphabetical order of the program name. Out of the studies focused on preventing violence, three referred to unnamed anti-bullying programs, which in the present review were labeled Anti-bullying_1 , Anti-bullying_2 , and Anti-bullying_3 ; the other studies on the topic referred to an anti-cyberbullying program named Cyber Friendly School ; an anti-bullying program named Friendly School ; a bystander program aimed at preventing dating violence and sexual violence, named Green Dots ; a program aimed at preventing bullying and aggression, named Learning Together ; and an anti-bullying program named STAC , which stands for Stealing the show, Turning it over, Accompanying others, Coaching compassion. The studies focused on promoting mental health comprised a school research initiative aimed at preventing depression, named Beyond blue ; an intervention aimed at promoting mental health, named Gatehouse Project ; and a program to prevent suicide risk, named Sources of Strengths . Out of the studies focused on promoting positive emotional and relational school climate, one referred to the Restorative Justice program, aimed at promoting healthy and trusting relationships within the school, and the other referred to a program aimed at the promotion of a good school climate, named SEHER , which stands for Strengthening Evidence base on scHool-based intErventions for pRomoting adolescent health.

A large majority of the studies were conducted in the USA, some were carried out in Australia and the UK, and a few studies in India and China. The studies varied in duration, ranging from one to seven school years, and the number of schools involved in the intervention, ranging from 1 to 75. About half of the studies involved students from all grades while the other half was targeted only for some grades. Lastly, the reports varied in its research design: the majority conducted experimental group comparisons (EGC), but also other quantitative research designs (O) were present along with some qualitative designs (QUAL). To make text and tables more readable, the 13 included programs were renamed with a program ID consisting of the initials of the program name. Similarly, the 22 included reports were renamed with a report ID , consisting in the program ID followed by the surname of the first author and the publication year, all separated by underscores. Report ID and Program ID are reported in Table 1 .

Assessment of Methodological Quality

To assess each report’s methodological quality, we searched in the literature for a rigorous and comprehensive set of indicators and eventually decided to use as a reference the standards for evidence-based practices identified by the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC, 2014 ), which include indicators on setting and program description, fidelity, and reliability of outcome measures. Although the standards were originally recommended for the specific field of special education, they are considered appropriate to evaluate studies in all educational settings and were previously used by Charlton et al. ( 2021 ) in a systematic review studying the effects of school-wide interventions on school climate perceptions. Given that our aim was not to identify evidence-based practices but more generally to assess the methodological quality of the reports included in the review, some of the identified indicators were not applicable to our material. For this reason, among all the indicators described in the document (CEC, 2014), we selected those that provided a general overview of each report’s methodological quality. The selected indicators, their corresponding number in the CEC document, and a short description for each are reported in Table 2 .

In more detail, we applied a more extensive set of indicators to reports which fit the CEC definition of experimental group comparison design (EGC, as reported in Table 1 ), where participants were divided into two or more groups, both randomly and non-randomly, to test the effects of the interventions. For reports based on qualitative analyses and on quantitative analyses not consistent with the EGC design (QUAL and O, as reported in Table 1 ), we used a more limited set of indicators (indicators 1 to 6, as described in Table 2 ) and included a brief description of the research aims and methods. In the assessment of methodological quality, interrater reliability was achieved as three independent researchers read each report in detail, and the attribution of each indicator was discussed and agreed upon.

The assessment of methodological quality for the EGC reports is summarized in Table 3 . The findings show that most studies were strong in contextualizing the research, clearly describing the intervention program (either directly or with references to previous work) and conducting quality analyses. Weak points emerged to be related to the assessment of fidelity implementation (indicators 4 and 5 in Table 3 ), both with reference to adherence to the intervention program and to the dosage received by participants. Results for studies with qualitative analyses or quantitative analyses not EGC are reported in Table 4 . Like the ECG reports, most of these studies appeared strong in contextualizing the research and describing the intervention program, while fidelity of implementation received less attention (indicators 4 and 5 in Table 4 ).

Levels of Active Student Participation

As required by our inclusion criteria, all the selected programs were based on interventions that solicited ASP. However, from the careful analysis of the studies, we realized that the program activities promoted very different forms of ASP. Three independent researchers thus considered in detail each activity described in the programs and eventually agreed to score it on a 5-point scale (see Table 5 ), distinguishing among activities that solicit various levels of ASP. The scale partly followed the school participation scale of the HBSC questionnaire as defined by De Róiste et al. ( 2012 ). It ranged from Very high levels of ASP, attributed to activities in which students were given a fully decision-making role, to Very low levels of ASP, given to activities in which students were just the recipients of activities delivered by adults. In line with our inclusion criteria, in no programs, students were involved solely as recipients of activities delivered by adults (Very low ASP). Moreover, levels were not mutually exclusive, so that each program might include different levels of ASP.

In Table 5 , we report all the considered ASP levels, with the specifically related activities, and the coding of each program. It should be specified that the distribution of activities in the various levels was based on a qualitative accurate analysis of the role attributed to students and not on the number of students involved in each program’s activities, which varied to a great extent. In more detail, Very high ASP was attributed to interventions in which students were involved in processes with a direct organizational impact on school roles, curricula, and policies; this included two types of activities, i.e., student involvement in decision-making processes and the formation of school action teams comprising students. High ASP was recognized when students were still involved in organizational activities, but their role was limited to the implementation of activities and did not directly impact on school curricula and policies; it consisted of three activities, i.e., presentation of students’ works, leading of activities for peers, and leading of activities for adults. Moderate ASP was attributed when students were asked to express their viewpoints and opinions, without having a decision-making power, however; it comprised activities in which students were called to express their points of view on various school issues, either by the provision of platforms to share ideas, concerns, or suggestions, or by the organization of interactive school assemblies, or by their involvement in surveys based on data collection (e.g., by means of questionnaires) on specific aspects of their school life. Low ASP was attributed when the students’ activation was limited to a specific task required within a structured format designed by other people, including training for student leaders, interactive group activities, and individual activities. Finally, activities were coded as Very low ASP when students were involved as the passive recipients of contents provided by adults, through lecture-style lessons, viewing of videos, or distribution of didactic material. The activities provided for in each program are described at length in the following paragraphs, considering activities scored in every specific level of ASP.

For the sake of completeness, in Table 5 , we added a final column in which we indicated additional program activities that involved the staff. They comprised the formation of school action teams made up of adults, training, and the provision of materials for the staff. As the description of these activities goes beyond the scope of our investigation, we will not describe them in detail.

Very High ASP: Making School Rules

As can be seen in Table 5 , activities implying involvement of students in decision-making processes were identified in six programs. In AB3, during a school assembly, students were invited to develop a whole-school anti-bullying policy, while in later activities, they were asked to identify strategies to be implemented in the school to prevent bullying. In CFS, school staff and student leaders conducted whole-school activities helping students to review school policies to promote a positive use of technology. In FS, the intervention aimed to help the transition between primary and secondary school was co‐developed with students who had already made such a transition. In GP, the use of peer support and leadership was encouraged to increase opportunities and skills for students to participate in decision-making processes within the school; in addition, at a classroom level, rules were negotiated by teachers and students and displayed in each classroom. In RJ, during the first year of implementation, staff and students developed a plan for pathways of primary, secondary, and tertiary restorative interventions; in the following years, students’ leadership roles and collective decision-making activities increased, so that students themselves were able to advance whole-school initiatives and activities, to map out course goals and determine which projects they would embrace. Finally, in SE, some health policies were discussed with the principal, teachers, and students before being finalized in a school action team meeting and disseminated at whole-school level.

Activities consisting in the creation of school action teams (or school action groups) including students and teachers were identified in three programs (see Table 5 ). In AB2, a school action group with both students and staff was formed to define action plans and training for staff on restorative practices at whole-school level and to implement a new school curriculum focusing on social and emotional skills. In LT, a school action group comprising around six students and six staff was formed to lay down school policies and coordinate interventions, based on the feedback from the student data collection. In SE, a school health promotion committee, consisting of representatives from the school board, parents, teachers, and students, was formed to discuss issues submitted by the students and to plan the activities for the future years based on the feedback from the activities already carried out. In addition, a peer group of 10 and 15 students from each class discussed health topics and student concerns with adult facilitators, in order to develop an action plan and to help in organizing various activities, such as contests and school assemblies.

High ASP: Organizing School Events

Three types of activities were included in this level of ASP. As reported in Table 5 , five programs solicited the creation of different student artifacts . AB1 included a student-made video on bullying to be presented to all the students. In GP, student artifacts were presented to audiences such as parents, other students, teachers, and members of the community. In SS, student leaders made presentations for peers to share personal examples of using the strengths provided by the program. In RJ, students engaged in collaborative, interactive writing activities based on analytical reflection for the realization of a rubric co-developed by students. SE included the contribution of all the students, teachers, and the principal in the realization of works like write-ups, poems, pictures, or artwork, on specific topics for a monthly wall magazine publication. SE also envisaged contests among students, such as poster-making and essay writing, linked to the monthly topic of the wall magazine.

Activities regarding the organization of student-led activities for peers were found in four programs (see Table 5 ). In CFS, student leaders (four to six in each intervention school) conducted at least three important whole-school activities to promote students’ positive use of technology for raising students’ awareness of their rights and responsibilities online; they also provided cyberbullying prevention trainings for peers. In SS, student leaders (up to six in the school) conducted activities aimed at raising awareness of Sources of Strengths , generating conversations with other students, providing presentations about the strengths proposed by the program, and engaging peers to identify their own trusted adults. RJ included student-led restorative circles with students, workshops for students, and peer-to-peer mentorship on restorative practices. In SE, student leaders (between 10 and 15 in each class) conducted peer group meetings to discuss on relevant health topics.

In two programs, student-led activities for adults were organized (see Table 5 ). In CFS, student-led activities provided information to the teaching staff about the technologies used by students and cyberbullying prevention training given to parents. In RJ, circles and workshops on restorative practices were implemented by the students for the staff.

Moderate ASP: Expressing Personal Views

Three types of activities were included in this level of ASP. As can be seen in Table 5 , two programs provided platforms where students could express their personal views on various topics. In BB, students, families, and school staff were provided with platforms to share information and communication on mental health issues. In SE, platforms were used to raise concerns, make complaints, and give suggestions, either anonymously or by self-identifying, on the intervention topics.

Interactive assemblies for students to discuss on the main intervention topics were organized in three programs (see Table 5 ). AB1 provided a first interactive school assembly to discuss respect and bullying, and later assemblies at class level to further discuss the themes emerged during the whole-school assembly. Similarly, AB3 included a school assembly where students were encouraged to get involved in the development of a whole-school anti-bullying policy, followed by three lessons during which the class teacher facilitated a discussion in each class aimed to raise awareness about bullying and to think about school-based solutions. SE included group discussions for generating awareness about health issues, to be discussed during the school assemblies that took place four times a month.

In six programs, students were given a voice by data collections to be used in the process of school changes (see Table 5 ). AB1 included a bullying report form that students, in addition to staff and parents, filled in to report bullying incidents. AB3 provided feedback from student data collection during the school assembly as a basis for discussing whole-school anti-bullying strategies. In LT, annual reports on students’ needs, drawing from student surveys in relation to bullying, aggression, and school experiences, guided the action teams to define school policies and coordinate interventions. In BB, summaries of student and staff data on current school structures, policies, programs, and practices related to student well-being, collected annually, were used by the team to create an “action plan” for changes across the school, both at the classroom and whole-school level. In GP, the profile emerging from the student surveys on school environment guided school teams in the definition of priority areas and strategies within each school, both by coordinating existing health promotional work and introducing new strategies that met the needs of a specific school. In SE, the school action team planned school activities based on reports and discussions on issues presented by the students.

Low ASP: Trainings

A low level of ASP was identified in three types of activities. As can be seen in Table 5 , four programs included trainings for student peer leaders . CFS provided a 10-h training for peer leaders to lead whole-school activities on the positive use of technology. GD provided a 5-h bystander training for student leaders to recognize situations and behaviors that could lead to violence or abuse and to identify active bystander behaviors to be performed either individually or collectively to reduce the risk or effect of violence. ST provided a 90-min training session and two 15-min booster sessions on bullying, which included icebreaker exercises, hands-on activities, and role plays. SS provided a 4-h interactive training for peer leaders aimed at developing protective resources in themselves and encouraging peers to grow such resources as well.