Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

, MD, MPH, University of California San Diego

- Symptoms and Signs

More Information

- 3D Models (0)

- Calculators (0)

Gonorrhea is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae . It typically infects epithelia of the urethra, cervix, rectum, pharynx, or conjunctivae, causing irritation or pain and purulent discharge. Dissemination to skin and joints, which is uncommon, causes sores on the skin, fever, and migratory polyarthritis or pauciarticular septic arthritis. Diagnosis is by microscopy, culture, or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Several oral or injectable antibiotics can be used, but drug resistance is an increasing problem.

(See also Overview of Sexually Transmitted Infections Overview of Sexually Transmitted Infections Sexually transmitted infection (STI) refers to infection with a pathogen that is transmitted through blood, semen, vaginal fluids, or other body fluids during oral, anal, or genital sex with... read more .)

N. gonorrhoeae is a gram-negative diplococcus that occurs only in humans and is almost always transmitted by sexual contact. Urethral and cervical infections are most common, but infection in the pharynx or rectum can occur after oral or anal intercourse, and conjunctivitis may follow contamination of the eye.

Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) due to hematogenous spread occurs in 1% of cases, predominantly in women. DGI typically affects the skin, tendon sheaths, and joints. Pericarditis, endocarditis, meningitis, and perihepatitis occur rarely.

1. Holmes KK, Johnson DW, Trostle HJ : An estimate of the risk of men acquiring gonorrhea by sexual contact with infected females. Am J Epidemiol 91(2):170-174, 1970. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121125

Symptoms and Signs of Gonorrhea

About 10 to 20% of infected women and very few infected men are asymptomatic. About 25% of men have minimal symptoms.

Male urethritis has an incubation period from 2 to 14 days. Onset is usually marked by mild discomfort in the urethra, followed by more severe penile tenderness and pain, dysuria, and a purulent discharge. Urinary frequency and urgency may develop as the infection spreads to the posterior urethra. Examination detects a purulent, yellow-green urethral discharge, and the meatus may be inflamed.

Pelvic inflammatory disease Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is a polymicrobial infection of the upper female genital tract: the cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries; abscess may occur. PID may be caused by sexually... read more occurs in 10 to 20% of infected women. PID may include salpingitis, pelvic peritonitis, and pelvic abscesses and may cause lower abdominal discomfort (typically bilateral), dyspareunia, and marked tenderness on palpation of the abdomen, adnexa, or cervix.

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is gonococcal (or chlamydial) perihepatitis that occurs predominantly in women and causes right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting, often mimicking biliary or hepatic disease.

Rectal gonorrhea is usually asymptomatic. It occurs predominantly in men practicing receptive anal intercourse and can occur in women who participate in anal sex. Symptoms include rectal itching, a cloudy rectal discharge, bleeding, and constipation—all of varying severity. Examination with a proctoscope may detect erythema or mucopurulent exudate on the rectal wall.

Gonococcal pharyngitis is usually asymptomatic but may cause sore throat. N. gonorrhoeae must be distinguished from N. meningitidis and other closely related organisms that are often present in the throat without causing symptoms or harm.

Gonococcal septic arthritis is a more localized form of DGI that results in a painful arthritis with effusion, usually of 1 or 2 large joints such as the knees, ankles, wrists, or elbows. Some patients present with or have a history of skin lesions of DGI. Onset is often acute, usually with fever, severe joint pain, and limitation of movement. Infected joints are swollen, and the overlying skin may be warm and red.

Diagnosis of Gonorrhea

Nucleic acid–based testing

Gram staining and culture

Gonorrhea is diagnosed when gonococci are detected via microscopic examination using a nucleic acid–based test, Gram stain, or culture of genital fluids, blood, or joint fluids (obtained by needle aspiration).

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) may be done on genital, rectal, or oral swabs and can detect both gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. NAATs further increase the sensitivity adequately to enable testing of urine samples in both sexes.

Gram stain is sensitive and specific for gonorrhea in men with urethral discharge; gram-negative intracellular diplococci typically are seen. Gram stain is much less accurate for infections of the cervix, pharynx, and rectum and is not recommended for diagnosis at these sites.

Culture is sensitive and specific, but because gonococci are fragile and fastidious, samples taken using a swab need to be rapidly plated on an appropriate medium (eg, modified Thayer-Martin) and transported to the laboratory in a carbon dioxide–containing environment. Blood and joint fluid samples should be sent to the laboratory with notification that gonococcal infection is suspected. Because NAATs have replaced culture in most laboratories, finding a laboratory that can provide culture and sensitivity testing may be difficult and require consultation with a public health or infectious disease specialist.

Men with urethritis

Men with obvious urethral discharge may be treated presumptively if likelihood of follow-up is questionable or if clinic-based diagnostic tools are not available.

Samples for Gram staining can be obtained by touching a swab or slide to the end of the penis to collect discharge. Gram stain does not identify chlamydiae, so urine or swab samples for NAAT are obtained.

Women with cervicitis or pelvic inflammatory disease

A cervical swab should be sent for culture or NAAT. If a pelvic examination is not possible, NAAT of a urine sample or self-collected vaginal swab can detect gonococcal (and chlamydial) infections rapidly and reliably.

Pharyngeal or rectal exposures

Swabs of the affected area are sent for culture or NAAT.

Arthritis, disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), or both

An affected joint should be aspirated, and fluid should be sent for culture and routine analysis (see arthrocentesis Arthrocentesis Some musculoskeletal disorders affect primarily the joints, causing arthritis. Others affect primarily the bones (eg, fractures, Paget disease of bone, tumors), muscles (eg, myositis), peripheral... read more ). Patients with skin lesions, systemic symptoms, or both should have blood, urethral, cervical, and rectal cultures or NAAT. In about 30 to 40% of patients with DGI, blood cultures are positive during the first week of illness. With gonococcal arthritis, blood cultures are less often positive, but cultures of joint fluids are usually positive. Joint fluid is usually cloudy to purulent because of large numbers of white blood cells (typically > 20,000/microliter).

Diagnosis reference

1. Bazan JA, Peterson AS, Kirkcaldy RD, et al . Notes from the field. Increase in Neisseria meningitidis –associated urethritis among men at two sentinel clinics — Columbus, Ohio, and Oakland County, Michigan, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:550–552, 2016. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6521a5external icon

Screening for Gonorrhea

Asymptomatic patients considered at high risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) can be screened by NAAT of urine samples, thus not requiring invasive procedures to collect samples from genital sites. The following are based on CDC's Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) Treatment Guidelines, 2021 .

Women are screened annually if they are sexually active and < 25 years of age or if they are ≥ 25 years of age, sexually active, and have one or more of the following risk factors:

Have a history of a prior STI

Engage in high-risk sexual behavior (eg, have a new sex partner or multiple sex partners; engage in sex work; or use condoms inconsistently when not in a mutually monogamous relationship)

Have a partner who has an STI or engages in high-risk behavior (eg, a sex partner who has concurrent partners)

Have a history of incarceration

Pregnant women who are < 25 years or who are ≥ 25 years with one or more of the risk factors are screened during their first prenatal visit and again during their 3rd trimester for women who are < 25 or at high risk.

There is insufficient evidence for screening heterosexual men who are at low risk for infection.

Men who have sex with men are screened at least annually if they have been sexually active within the previous year (for insertive intercourse, urine screen; for receptive intercourse, rectal swab; and for oral intercourse, pharyngeal swab), regardless of condom use. Those at increased risk (eg, with HIV infection, receive preexposure prophylaxis with antiretrovirals, have multiple sex partners, or whose partner has multiple partners) should be screened more frequently, at 3 to 6-month intervals.

Transgender and gender diverse people are screened if they are sexually active on the basis of sexual practices and anatomy (eg, annual screening for all people with a cervix who are < 25 years old; if ≥ 25 years old, people with a cervix should be screened annually if at increased risk; rectal swab based on reported sexual behaviors and exposure).

(See also the US Preventive Services Task Force’s summary of recommendations regarding screening for gonorrhea .)

Treatment of Gonorrhea

For uncomplicated infection, a single dose of ceftriaxone

Concomitant treatment for chlamydial infection

Treatment of sex partners

For disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) with arthritis, a longer course of parenteral antibiotics

Uncomplicated gonococcal infection of the urethra, cervix, rectum, and pharynx is treated with the following:

A single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg IM (1 g IM for patients weighing ≥ 150 kg)

If ceftriaxone is not available, use cefixime 800 mg orally in a single dose.

If chlamydial infection has not been excluded, treat for chlamydia with doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days. In patients who have a doxycycline allergy, treat for chlamydia with a single dose of azithromycin 1 g orally.

Patients who are allergic to cephalosporins (including ceftriaxone ) are treated with

Gentamicin 240 mg IM in a single dose plus azithromycin 2 g orally in a single dose

Gonococcal purulent arthritis usually requires repeated synovial fluid drainage either with repeated arthrocentesis or arthroscopically. Initially, the joint is immobilized in a functional position. Passive range-of-motion exercises should be started as soon as patients can tolerate them. Once pain subsides, more active exercises, with stretching and muscle strengthening, should begin. Over 95% of patients treated for gonococcal arthritis recover complete joint function. Because sterile joint fluid accumulations (effusions) may develop and persist for prolonged periods, an anti-inflammatory drug may be beneficial.

Posttreatment cultures are unnecessary if symptomatic response is adequate. However, for patients with symptoms for > 7 days, specimens should be obtained, cultured, and tested for antimicrobial sensitivity.

Patients should abstain from sexual activity until treatment is completed to avoid infecting sex partners.

Sex partners

All sex partners who have had sexual contact with the patient within 60 days should be tested for gonorrhea and other STIs and treated if results are positive. Sex partners with contact within 2 weeks should be treated presumptively for gonorrhea (epidemiologic treatment).

Treatment reference

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021 : Gonococcal Infections Among Adolescents and Adults. Accessed June 27, 2022.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection typically causes uncomplicated infection of the urethra, cervix, rectum, pharynx, and/or conjunctivae.

Sometimes gonorrhea spreads to the adnexa, causing salpingitis, or disseminates to skin and/or joints, causing skin lesions or septic arthritis.

Diagnose using NAAT, but culture and sensitivity testing should be done when needed to detect antimicrobial resistance.

Screen high-risk patients using NAAT.

Treat uncomplicated infection with a single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg IM (1 g IM for patients weighing ≥ 150 kg); add oral doxycycline (100 mg twice a day for 7 days) when chlamydial infection has not been excluded.

The following English-language resource may be useful. Please note that THE MANUAL is not responsible for the content of this resource.

US Preventive Services Task Force: Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: Screening : A review of evidence that screening tests can accurately detect chlamydia and gonorrhea

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada) — dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the MSD Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge.

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Manual

- IN THIS TOPIC

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

To determine whether you have gonorrhea, your healthcare professional will analyze a sample of cells. Samples can be collected with:

- A urine test. This can help identify bacteria in your urethra.

- A swab of the affected area. A swab of your throat, urethra, vagina or rectum can collect bacteria that can be identified in a lab.

Testing for other sexually transmitted infections

Your healthcare professional may recommend tests for other sexually transmitted infections. Gonorrhea increases your risk of these infections, particularly chlamydia, which often accompanies gonorrhea.

Testing for HIV also is recommended for anyone diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection. Depending on your risk factors, tests for other sexually transmitted infections could be beneficial as well.

Gonorrhea treatment in adults

Adults with gonorrhea are treated with antibiotics. Due to emerging strains of drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium that causes gonorrhea, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that uncomplicated gonorrhea be treated with the antibiotic ceftriaxone. This antibiotic is given as a shot, also called an injection.

After getting the antibiotic, you can still spread the infection to others for up to seven days. So avoid sexual activity for at least seven days.

Three months after treatment, the CDC also recommends getting tested for gonorrhea again. This is to make sure people haven't been reinfected with the bacteria, which can happen if sex partners aren't treated, or new sex partners have the bacteria.

Gonorrhea treatment for partners

Your sexual partner or partners from the last 60 days also need to be screened and treated, even if they have no symptoms. If you are treated for gonorrhea and your sexual partners aren't treated, you can become infected again through sexual contact. Make sure to wait until seven days after a partner is treated before having any sexual contact.

Gonorrhea treatment for babies

Babies who develop gonorrhea after being born to someone with the infection can be treated with antibiotics.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Preparing for your appointment

You'll likely see your primary healthcare professional. Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, if you have any, including those that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment, and when they began.

- All medicine, vitamins or other supplements you take, including doses.

- Questions to ask your healthcare professional.

For gonorrhea, questions to ask include:

- What tests do I need?

- Should I be tested for other sexually transmitted infections?

- Should my partner be tested for gonorrhea?

- How long should I wait before resuming sexual activity?

- How can I prevent gonorrhea in the future?

- What gonorrhea complications should I be alert for?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

- Will I need a follow-up visit?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Questions your healthcare professional is likely to ask you include:

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Have you been exposed to sexually transmitted infections?

What you can do in the meantime

Avoid sexual activity until you see your healthcare professional. Alert your sex partners that you're having symptoms so that they can arrange to see a member of their healthcare teams for testing.

- Gonorrhea: CDC fact sheet (detailed version). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.

- Ghanem KG. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in adults and adolescents. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.

- Gonorrhea. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/gonorrhea. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.

- Gonorrhea. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds/gonorrhea. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and nongonococcal urethritis. Mayo Clinic; 2023.

- Speer ME. Gonococcal infection in the newborn. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.

- Workowski KA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 2021; doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

NICOLE YONKE, MD, MPH, MIRANDA ARAGÓN, MD, AND JENNIFER K. PHILLIPS, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(4):388-396

Related Letter to the Editor: Doxycycline Preferred for the Treatment of Chlamydia

Patient information: See related handouts on chlamydia , written by the authors of this article, and on gonorrhea , which has been adapted from a previously published AFP article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are increasing in the United States. Because most infections are asymptomatic, screening is key to preventing complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility and decreasing community and vertical neonatal transmission. All sexually active people with a cervix who are younger than 25 years and older people with a cervix who have risk factors should be screened annually for chlamydial and gonococcal infections. Sexually active men who have sex with men should be screened at least annually. Physicians should obtain a sexual history free from assumptions about sex partners or practices. Acceptable specimen types for testing include vaginal, endocervical, rectal, pharyngeal, and urethral swabs, and first-stream urine samples. Uncomplicated gonococcal infection should be treated with a single 500-mg dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone in people weighing less than 331 lb (150 kg). Preferred chlamydia treatment is a seven-day course of doxycycline, 100 mg taken by mouth twice per day. All nonpregnant people should be tested for reinfection approximately three months after treatment or at the first visit in the 12 months after treatment. Pregnant patients diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea should have a test of cure four weeks after treatment.

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are the most common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States and are required to be reported to state health departments. Between 2015 and 2019, reported chlamydial infections increased by 19%, and reported gonococcal infections increased by 53%. 1 These bacteria commonly infect the urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal sites but can become disseminated to affect multiple organ systems. Untreated infections may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease; scarring of fallopian tubes, which can increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy; infertility; easier transmission of new HIV infection; and vertical neonatal transmission. 2

Risk Factors

Young people 15 to 24 years of age account for 61% of all newly diagnosed STIs. 1 Racial and ethnic minorities, men who have sex with men (MSM), and transgender and gender diverse people are at higher risk of STIs. Inequitable access to health insurance and physicians, language barriers, and distrust of medical systems because of discrimination account for some of these disparities, independent of individual sexual behavior. 3 , 4 Other risk factors are reviewed in Table 1 . 2

Taking a thorough sexual history is important to identify overall risk of infection, as well as anatomic site-specific risk factors. Physicians should create supportive spaces where patients feel safe sharing information by using open-ended questions; avoiding assumptions regarding sexual preferences, practices, and gender/sex; and normalizing diverse sexual experiences. To obtain a complete sexual history, the five P’s (partners, practices, pregnancy attitudes, previous STIs, and protection from STIs) model can be used as outlined in Table 2 . 2 , 5

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends behavioral counseling on condom use, communication strategies for safer sex, and problem solving with those at increased risk of STIs. 6 Adolescents and adults diagnosed with an STI in the past year, people reporting irregular condom use, and those with multiple partners or with partners belonging to a high-risk group are at increased risk. Physicians should emphasize barrier protection as the best way to prevent STIs. 2

The USPSTF and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend annual screening for chlamydial and gonococcal infections to prevent infertility and pelvic inflammatory disease in sexually active people 24 years and younger with a cervix and in older people with a cervix who have risk factors. 2 , 7 The CDC also recommends at least annual screening for MSM based on their risk factors. Screening should include the pharynx, urethra, and rectum based on reported anatomic sites of exposure. After discussion with the patient, it may be necessary to screen those sites even without reported exposure because of underreporting of sexual practices. 2 Table 3 summarizes screening recommendations for chlamydial and gonococcal infections. 2 , 8 There are significant gaps in research as it pertains to screening transgender and gender diverse patients. 9 The CDC recommends screening based on an individual’s current anatomy and sexual practices. 2

Screening for urogenital infections only and neglecting pharyngeal and rectal sites of exposure will miss a substantial proportion of chlamydial and gonococcal infections. 10 In one study of women who engaged in oral or anal sex with men, the prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea was 3.5%; rectal gonorrhea, 4.8%; and rectal chlamydia, 11.8%. 10 Pharyngeal and rectal screening may be offered to people with female anatomy based on sexual practices and shared decision-making. 2 Current evidence for screening extra-genital sites is strongest for MSM. Urine-only screening in an STI clinic misses 83% of infections among MSM. 11 They should be screened at each anatomic site of sexual exposure, regardless of condom use, at least annually. 2 Routine testing for chlamydial infections of the oropharynx is not recommended, but many laboratories will test for gonococcal and chlamydial infections simultaneously. 2 If oropharyngeal chlamydia is diagnosed, it should be treated to decrease the risk of transmission. 2

Presentation

Most chlamydial and gonococcal infections are asymptomatic. 8 Symptoms of infection are reviewed in Table 4 . 2 Because dysuria may be a symptom of chlamydial and gonococcal infections and causes leukocytes on urinalysis, women presenting with dysuria may be inaccurately diagnosed with a urinary tract infection if STI testing is not performed. 12 , 13 In women at risk for STIs or with a negative urine culture, physicians can consider STI testing in those presenting with dysuria. A pelvic examination is not required for diagnosis and may not improve the diagnosis of chlamydia and gonorrhea beyond history and diagnostic testing. 14 However, if pelvic inflammatory disease is suspected, a pelvic examination should be performed. The differential diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections is summarized in Table 5 . 2 , 15

Diagnostic Testing

The CDC recommends using nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for the diagnosis of gonococcal or chlamydial infections because it is the most sensitive. 2 Specimens can be taken from a first-stream urine sample without urethral cleansing before collection. 2 Clinician- or patient-collected vaginal or endocervical swabs are also acceptable specimens. Self-collected vaginal swabs are as sensitive as clinician-collected swabs and are preferred by patients. 16 , 17 A recent meta-analysis showed that urine samples and vaginal and endocervical swabs have similar sensitivity. 17 For patients with male genitalia, a patient- or clinician-collected urethral swab may also be obtained, although a urine specimen is preferred. 2

In 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, which use NAAT, for extragenital swabs of the throat and rectum. 18 The binx health io CT/NG assay, Visby Medical Sexual Health Test NAAT, and Cepheid Xpert CT/NG (not a waived test by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) are point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections. 19 Point-of-care testing provides same-day results, decreases loss to follow-up, and reduces overtreatment. 20 , 21

All people who test positive or report known exposure to C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae should be treated. Patients and their partners should be advised to abstain from sex for seven days after completing a single-dose regimen or until the completion of a seven-day treatment course and resolution of symptoms. 2 Nonpregnant people should be tested for reinfection approximately three months after treatment or at the first visit in the 12 months after treatment. Follow-up care recommendations are reviewed in Table 6 . 2 , 22 , 23

Patients presenting clinically with nongonococcal urethritis can be treated empirically at the time of evaluation while diagnostic testing is pending. Cervicitis should be treated presumptively in those younger than 25 years or those at high risk of infection if NAAT is not available or follow-up is uncertain.

CHLAMYDIAL TREATMENT

Although spontaneous clearance of chlamydial infections is possible, people with positive test results should always be treated. 24 Because of increasing macrolide resistance, the recommended treatment for non-pregnant people is now doxycycline, 100 mg, twice per day for seven days. 2 Physicians may alternatively choose to treat patients with a single 1-g dose of azithromycin, especially when adherence to a multidose regimen may be a concern. 2 Treatment regimens are reviewed in Table 7 . 2 , 22 , 23

GONOCOCCAL TREATMENT

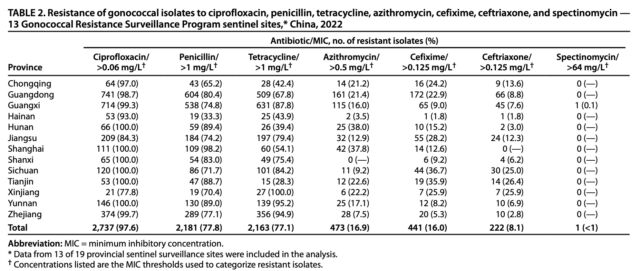

In 2018, more than one-half of cases of gonococcal infection were estimated to be resistant to at least one drug, leading the CDC to change treatment recommendations to higher doses of ceftriaxone 25 ( Table 8 2 , 15 , 25 ) . Azithromycin is no longer a recommended therapy for nonpregnant individuals because of an observed sevenfold increase in gonococcal resistance between 2013 and 2018. 25

UNRESOLVED SYMPTOMS

Most treatment failures are caused by reinfection from sex partners who have not received adequate treatment, rather than treatment failure from antimicrobial resistance. 2 If symptoms do not resolve or a test is persistently positive in a situation in which reinfection seems unlikely (i.e., the patient has reported no new sexual contact and is taking medication as prescribed), an infectious disease specialist and local health department should be consulted in case of possible antimicrobial resistance. 2

PARTNER EVALUATION AND EXPEDITED PARTNER THERAPY

If seeking care in person is not possible, expedited partner therapy is a strategy in which sex partners of a person diagnosed with a chlamydial or gonococcal infection within the past 60 days can be prescribed treatment without being seen by the physician. This strategy is supported by the American Academy of Family Physicians. 2 , 26 If the diagnosed person has not had a sex partner in the past 60 days, the most recent sex partner can be offered treatment. Sex partners with symptoms should be referred for evaluation and treatment. 2 Laws in 46 states permit expedited partner therapy. 27 Because recommended gonococcal treatment is based on intramuscular administration of medication, every effort should be made to see partners of infected patients in person for treatment and testing for other STIs. 28 If permissible by state law and the partner is highly unlikely to receive care, partners of those with gonococcal infections may be treated with a single dose of cefixime (Suprax), 800 mg orally, with the addition of 100 mg of oral doxycycline twice per day for seven days if chlamydial infection was not excluded. 28 Written instructions should be given to patients to convey to their partners how to take the medication, warnings about side effects and allergies, when to seek medical care, and STI education. 2 The best evidence for use of expedited partner therapy services is for male partners of women with gonococcal or chlamydial infections. 27 The risk of missing concomitant infections in MSM requires a more nuanced discussion, but these patients may be offered expedited partner therapy through shared decision-making. 28

LYMPHOGRANULOMA VENEREUM

Lymphogranuloma venereum is caused by a C. trachomatis serovar and can become invasive and cause colorectal fistulas and strictures. Treatment should be started presumptively at the initial visit to prevent complications if there is clinical suspicion for lymphogranuloma venereum. 2 Partners should be evaluated and treated empirically with a non–lymphogranuloma venereum chlamydial infection regimen. 2

Gonococcal and chlamydial infections in pregnancy are associated with increased risks, including preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, stillbirth, low-birth-weight infants, and neonatal infection. 29 , 30 Pregnant patients should be screened as outlined in Table 3 . 2 , 8 Those at high risk of infection should be screened again in the third trimester. 2 Anyone diagnosed with a gonococcal or chlamydial infection during pregnancy should have a test of cure approximately four weeks after treatment, at three months after diagnosis, and in their third trimester. 2

NEONATAL INFECTIONS

The prevalence of perinatal gonococcal infections is 0.2 to 0.4 cases per 100,000 live births. 31 The USPSTF recommends universal prophylaxis with ocular erythromycin 0.5% ointment to prevent gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. The risk of infection without prophylaxis is 30% to 40%, and it can cause blindness as early as 24 hours after birth. 31 N. gonorrhoeae can also cause septic arthritis, meningitis, rhinitis, vaginitis, urethritis, pneumonia, and skin infections in neonates. 2 Asymptomatic newborns exposed to gonorrhea at birth from an untreated birthing parent should be swabbed for infection at the conjunctiva, oropharynx, vagina, and rectum and presumptively treated for gonorrhea. 2

Neonates are at high risk of contracting an infection if chlamydia is untreated in pregnancy. 2 , 32 Infants exposed during birth do not need to receive chlamydial-specific prophylactic antibiotics but should be monitored clinically for symptoms. 2 Ophthalmia neonatorum presents a few days to several weeks after birth with eyelid edema, discharge, and ocular congestion. 2 , 32 Chlamydial infections of the eye are not prevented by prophylactic erythromycin ointment. 32 Unlike trachoma, which is a chronic infection spread through close contact, clothes, and flies, ophthalmia neonatorum does not result in scarring and blindness. Diagnosis of ophthalmia neonatorum can be made by swabbing the conjunctiva for culture, direct fluorescence antibody testing, or NAAT. 2 The recommended treatment is oral erythromycin. 2 There should be close follow-up because a second course may be required. 2 C. trachomatis can also cause neonatal pneumonia. Infants present between two and 19 weeks of age with a staccato cough, tachypnea, rhinorrhea, and rales. 2 , 32 Exposed infants are at high risk; if they present with pneumonia, they should be treated empirically for chlamydial infection while awaiting test results from culture, direct fluorescence antibody testing (lower sensitivity), or NAAT (not FDA approved for the nasopharynx). 2 , 32

Any child diagnosed with gonococcal or chlamydial infections should be evaluated for sexual abuse. 2 , 32 Although perinatally transmitted chlamydial infections can be found in children up to three years of age, sexual abuse is the most common cause of infection in children. 2

MANAGEMENT DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Disparities in STI testing have been more pronounced due to reallocation of resources for SARS-CoV-2 testing and decreased testing due to social distancing and stay-at-home orders. 3 , 19 However, telemedicine use has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and is well-suited for STI screening because physical examination is not essential for diagnosis or treatment. 14 , 33 At-home C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae self-testing kits are not FDA approved; however, multiple studies have found that when patients are instructed by a physician via telemedicine, self-collected swabs at home will diagnose cases similarly to office-collected samples, with increased volume of testing offsetting a slightly lower test sensitivity. 19 , 34 – 36 Physicians can safely incorporate home-based testing and treatment into telehealth practice.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Mishori, et al. 23 ; Mayor, et al. 15 ; Miller 37 ; and Miller . 38

Data Sources: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential Evidence Plus, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and American Academy of Family Physicians websites were reviewed for relevant publications. A PubMed search was conducted using the terms Neisseria gonorrhoeae , Chlamydia trachomatis , diagnosis, and treatment for the past 10 years including English language, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials, reviews, and systematic reviews. Search dates: January 28, 2021; February 14, 2021; March 30, 2021; July 25, 2021; and November 27, 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed November 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2019/default.htm

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70(4):1-187.

Lieberman JA, Cannon CA, Bourassa LA. Laboratory perspective on racial disparities in sexually transmitted infections. J Appl Lab Med. 2021;6(1):264-273.

Hamilton DT, Morris M. The racial disparities in STI in the U.S.: concurrency, STI prevalence, and heterogeneity in partner selection. Epidemics. 2015;11:56-61.

Savoy M, O’Gurek D, Brown-James A. Sexual health history: techniques and tips. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(5):286-293. Accessed November 28, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2020/0301/p286.html

- Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324(7):674-681.

- Cantor A, Dana T, Griffin JC, et al. Screening for chlamydial and gonococcal infections: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326(10):957-966.

Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Prev Med. 2003;36(4):502-509.

- Van Gerwen OT, Jani A, Long DM, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus in transgender persons: a systematic review. Transgend Health. 2020;5(2):90-103.

- Bamberger DM, Graham G, Dennis L, et al. Extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia among men and women according to type of sexual exposure. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46(5):329-334.

- Marcus JL, Bernstein KT, Kohn RP, et al. Infections missed by urethral-only screening for chlamydia or gonorrhea detection among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(10):922-924.

- Tomas ME, Getman D, Donskey CJ, et al. Overdiagnosis of urinary tract infection and underdiagnosis of sexually transmitted infection in adult women presenting to an emergency department. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(8):2686-2692.

- Shipman SB, Risinger CR, Evans CM, et al. High prevalence of sterile pyuria in the setting of sexually transmitted infection in women presenting to an emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):282-286.

- Farrukh S, Sivitz AB, Onogul B, et al. The additive value of pelvic examinations to history in predicting sexually transmitted infections for young female patients with suspected cervicitis or pelvic inflammatory disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):703-712.e1.

Mayor MT, Roett MA, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of gonococcal infections [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician . 2013;87(3):163]. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(10):931-938. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1115/p931.html

- Lunny C, Taylor D, Hoang L, et al. Self-collected versus clinician-collected sampling for chlamydia and gonorrhea screening: a systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132776.

- Rönn MM, Mc Grath-Lone L, Davies B, et al. Evaluation of the performance of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) in detection of chlamydia and gonorrhoea infection in vaginal specimens relative to patient infection status: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e022510.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA news release: FDA clears first diagnostic tests for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea. May 23, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-clears-first-diagnostic-tests-extragenital-testing-chlamydia-and-gonorrhea

- Kersh EN, Shukla M, Raphael BH, et al. At-home specimen self-collection and self-testing for sexually transmitted infection screening demand accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of laboratory implementation issues. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(11):e0264620.

- Van Der Pol B, Taylor SN, Mena L, et al. Evaluation of the performance of a point-of-care test for chlamydia and gonorrhea. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204819.

- Gaydos CA, Ako MC, Lewis M, et al. Use of a rapid diagnostic for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae for women in the emergency department can improve clinical management: report of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(1):36-44.

- Dombrowski JC, Wierzbicki MR, Newman LM, et al. Doxycycline versus azithromycin for the treatment of rectal chlamydia in men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(5):824-831.

Mishori R, McClaskey EL, WinklerPrins VJ. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: screening, diagnosis, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(12):1127-1132. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1215/p1127.html

- Geisler WM, Lensing SY, Press CG, et al. Spontaneous resolution of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women and protection from reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(12):1850-1856.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(50):1911-1916.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Expedited partner therapy. Accessed August 1, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/expedited-partner-therapy.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expedited partner therapy. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed November 27, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/default.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance on the use of expedited partner therapy in the treatment of gonorrhea. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed November 27, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/gc-guidance.htm

- He W, Jin Y, Zhu H, et al. Effect of Chlamydia trachomatis on adverse pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302(3):553-567.

- Vallely LM, Egli-Gany D, Wand H, et al. Adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(2):104-111.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321(4):394-398.

Baker CJ. Red Book: Atlas of Pediatric Infectious Diseases . 4th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2020.

- Car J, Koh GCH, Foong PS, et al. Video consultations in primary and specialist care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. BMJ. 2020;371:m3945.

- Fajardo-Bernal L, Aponte-Gonzalez J, Vigil P, et al. Home-based versus clinic-based specimen collection in the management of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD011317.

- Carnevale C, Richards P, Cohall R, et al. At-home testing for sexually transmitted infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(1):e11-e14.

- Chow EPF, Bradshaw CS, Williamson DA, et al. Changing from clinician-collected to self-collected throat swabs for oropharyngeal gonorrhea and chlamydia screening among men who have sex with men. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(9):e01215-20.

Miller KE. Diagnosis and treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(10):1779-1784. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0515/p1779.html

Miller KE. Diagnosis and treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician . 2008;77(7) 920]. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(8):1411-1416. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0415/p1411.html

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2022 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Mammary Glands

- Fallopian Tubes

- Supporting Ligaments

- Reproductive System

- Gametogenesis

- Placental Development

- Maternal Adaptations

- Menstrual Cycle

- Antenatal Care

- Small for Gestational Age

- Large for Gestational Age

- RBC Isoimmunisation

- Prematurity

- Prolonged Pregnancy

- Multiple Pregnancy

- Miscarriage

- Recurrent Miscarriage

- Ectopic Pregnancy

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

- Breech Presentation

- Abnormal lie, Malpresentation and Malposition

- Oligohydramnios

- Polyhydramnios

- Placenta Praevia

- Placental Abruption

- Pre-Eclampsia

- Gestational Diabetes

- Headaches in Pregnancy

- Haematological

- Obstetric Cholestasis

- Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

- Epilepsy in Pregnancy

- Induction of Labour

- Operative Vaginal Delivery

- Prelabour Rupture of Membranes

- Caesarean Section

- Shoulder Dystocia

- Cord Prolapse

- Uterine Rupture

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism

- Primary PPH

- Secondary PPH

- Psychiatric Disease

- Postpartum Contraception

- Breastfeeding Problems

- Primary Dysmenorrhoea

- Amenorrhoea and Oligomenorrhoea

- Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

- Endometriosis

- Endometrial Cancer

- Adenomyosis

- Cervical Polyps

- Cervical Ectropion

- Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia + Cervical Screening

- Cervical Cancer

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- Ovarian Cysts & Tumours

- Urinary Incontinence

- Genitourinary Prolapses

- Bartholin's Cyst

- Lichen Sclerosus

- Vulval Carcinoma

- Introduction to Infertility

- Female Factor Infertility

- Male Factor Infertility

- Female Genital Mutilation

- Barrier Contraception

- Combined Hormonal

- Progesterone Only Hormonal

- Intrauterine System & Device

- Emergency Contraception

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Genital Warts

- Genital Herpes

- Trichomonas Vaginalis

- Bacterial Vaginosis

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- Obstetric History

- Gynaecological History

- Sexual History

- Obstetric Examination

- Speculum Examination

- Bimanual Examination

- Amniocentesis

- Chorionic Villus Sampling

- Hysterectomy

- Endometrial Ablation

- Tension-Free Vaginal Tape

- Contraceptive Implant

- Fitting an IUS or IUD

Original Author(s): Grace Fitzgerald Last updated: 11th June 2019 Revisions: 6

- 1 Pathophysiology

- 2 Risk Factors

- 3.1 Genital infection

- 3.2 Rectal infection

- 3.3 Pharyngeal infection

- 4 Differential Diagnoses

- 5 Investigations

- 6 Management

- 7 Complications

- 8 Gonorrhoea in Pregnancy

Gonorrhoea is a curable sexually transmitted infection caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae . In the UK, gonorrhoea is the second most common bacterial STI (after chlamydia) and predominantly affects people under the age of 25 and men who have sex with men.

Throughout this article we will discuss the pathophysiology of gonorrhoea, its clinical features, management and how it may affect pregnancy and the neonate.

Pathophysiology

Gonorrhoea is transmitted through unprotected vaginal/oral/anal sex and can also be vertically transmitted from mother to child.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative diplococcus that has a strong affinity for mucous membranes. The organism can infect the uterus, urethra, cervix, fallopian tubes, ovaries, testicles, rectum, throat and less commonly the eyes. Once adhered to the mucous membrane, it invades the host cell and causes acute inflammation. N. gonorrhoea also has surface proteins that bind to the receptors of immune cells thus preventing an immune response.

Risk Factors

The following are risk factors associated with gonorrhoea, most of which are common to other STIs:

- Aged <25 years

- Men who have sex with men

- Living in high density urban areas

- Previous gonorrhoea infection

- Multiple sexual partners

Clinical Features

While gonorrhoea is often asymptomatic, as occurs in around 50% of female cases, symptoms can usually develop 2-5 days following infection:

Genital infection

Figure 1. Vaginal discharge in female gonorrhoea infection

- Altered/increased vaginal discharge (commonly thin, watery, green or yellow)

- Dyspareunia

- Lower abdominal pain

- Rarely – intermenstrual and/or post-coital bleeding

- Mucopurulent endocervical discharge

- Easily induced cervical bleeding

- Pelvic tenderness

Often examination can be normal.

- Mucopurulent/purulent urethral discharge

- Epididymal tenderness

Rectal infection

- Usually asymptomatic

- Anal discharge

- Anal pain/discomfort

Pharyngeal infection

- Usually asymptomatic (>90%)

Differential Diagnoses

A full STI screen should be undertaken for a patient presenting with gonorrhoea due to the common presenting symptoms of various STIs.

In particular, it is often very difficult to clinically differentiate between gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection. These infections often co-exist and therefore empirical treatment for gonorrhoea has the aim of covering both the causative organisms.

Investigations

If someone has suspected gonorrhoea, they should be referred to a GUM clinic or other specialist sexual health service for specimens to be taken:

- Endocervical/vaginal swab – NAAT

- Endocervical/urethral swab – microscopy and culture

- First pass urine – NAAT

- Urethral/meatal swab – microscopy and culture

- Swabs for NAAT + microscopy & culture can be obtained from the throat, rectum or eye if indicated.

These swabs should then be sent for microscopy , culture or nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) . NAATs are the standard investigation for chlamydia and these tests often provide dual testing for both chlamydia and gonorrhea.

While waiting for these laboratory results the patient should be treated with empirical antibiotics if their signs and symptoms are indicative of gonorrhoea.

Following diagnosis of gonorrhoea, a patient should be treated with a single dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone 1g.

Patients should be offered screening for other STIs, especially chlamydia, as co-infections are common. People should be encouraged to contact previous sexual partners to advise them to be screened and treated empirically for gonorrhoea.

Future safe sex should also be encouraged and patients should abstain from sex until both partners have completed treatment. To ensure antibiotics have successfully treated a patient, a test of cure is recommended during a follow up appointment.

For full details please refer to the BASHH UK guidelines for the management of gonorrhoea .

Complications

If gonorrhoea is left untreated in females, it can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) , which can result in chronic pain, infertility and ectopic pregnancy. In males, gonorrhoea can spread from the urethra to the testes causing epididymo-orchitis which is painful but rarely leads to infertility. It can also lead to prostatitis . Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) is uncommon but can lead to joint pain and skin lesions.

A patient should be admitted to hospital if:

- Systemic symptoms are identified (e.g. malaise, joint pain, fever, rash) as this suggests disseminated gonorrhoea which can potentially develop into a life threatening infection such as gonococcal meningitis.

- Females show signs of complicated or severe pelvic inflammatory disease.

Gonorrhoea in Pregnancy

Having gonorrhoea during pregnancy may be associated with complications such as perinatal mortality, spontaneous abortion, premature labour and early fetal membrane rupture.

Figure 2. Neonatal conjunctivitis may develop if born to an untreated woman with gonorrhoea.

Gonorrhoea can be vertically transmitted during delivery from an untreated mother and this can cause the neonate to have gonococcal conjunctivitis, where the neonate will experience eye pain, redness and discharge. Prophylactic antibiotics can prevent this and treatment during pregnancy is the same as for uncomplicated gonorrhoea. For the infected neonate, urgent referal and appropriate treatment is necessary to prevent long term damage and blindness.

- Rarely - intermenstrual and/or post-coital bleeding

[start-clinical]

[end-clinical]

Found an error? Is our article missing some key information? Make the changes yourself here!

Once you've finished editing, click 'Submit for Review', and your changes will be reviewed by our team before publishing on the site.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site and to show you relevant advertising. To find out more, read our privacy policy .

Privacy Overview

- Help & Feedback

- About epocrates

Gonorrhea infection

Highlights & basics, diagnostic approach, risk factors, history & exam, differential diagnosis.

- Tx Approach

Emerging Tx

Complications.

PATIENT RESOURCES

Patient Instructions

Gonorrhea infection is a common STI caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae , a gram-negative diplococcus bacterium that is closely related to other human Neisseria species.

Men typically present with a urethral discharge; women are often asymptomatic, but may have vaginal discharge.

Risk factors include multiple sex partners in recent months, known partner with gonorrhea, drug use, prior STI, and men who have sex with men.

If left untreated, N gonorrhoeae can disseminate to areas of the body to cause skin and synovial infections; rarer complications include meningitis, endocarditis, and perihepatic abscesses.

High rates of antimicrobial resistance have been reported, and antibiotic treatment should be guided by local and national guidelines. The main treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea is monotherapy with single-dose intramuscular ceftriaxone.

The treatment of N gonorrhoeae is important in the prevention of infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy in women.

If acquired congenitally from an infected mother, the neonate can present with ophthalmia neonatorum, which left untreated can cause blindness.

Quick Reference

Key Factors

urethral discharge in men

Tenderness and/or swelling of the epididymis, mucopurulent or purulent exudate at the endocervix.

Other Factors

pelvic pain in women

Urethral irritation in men, dysuria in men, tenderness and/or swelling of testis, tenderness and/or swelling of prostate, anal pruritus, mucopurulent discharge from the rectum, rectal pain, rectal bleeding, vaginal discharge, cervical friability, uterine, adnexal, or cervical motion tenderness, uterine mass, anterior cervical lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, skin lesions (papules, bullae, petechiae, or necrotic) at extremities, polyarthritis, purpuric rash, positive brudzinski and kernig sign, focal cerebral signs, ophthalmia neonatorum, urethritis (infantile).

Diagnostics Tests

1st Tests to Order

nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)

Urinalysis in men, gram stain of urine sediment, gram stain of urethral discharge, syphilis test.

Other Tests to consider

transvaginal ultrasound

Pelvic ct/mri, treatment options, nonpregnant >45 kg: urogenital/anorectal or pharyngeal infection (excluding complicated genitourinary infection).

with history of sexual assault

nonpregnant >45 kg: complicated genitourinary infection

with mild to moderate pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

with severe pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

with epididymitis (suspected sexually transmitted)

with conjunctivitis

Common Vignette 1

Common Vignette 2

Other Presentations

Epidemiology

Pathophysiology.

- Sheldon Morris, MD, MPH

- Vani Dandolu, MD, MPH

- Eva Jungmann, FRCP MSc

This gram-stained micrograph of a rectal smear specimen reveals the presence of diplococcal Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria

This patient presented with symptoms later diagnosed as due to gonococcal pharyngitis

Gonococcal conjunctivitis of the right eye

Gonococcal arthritic patient with inflammation of the skin of her right arm due to a disseminated Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterial infection

Cutaneous lesions on the left ankle and calf due to a disseminated Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection

Gonococcal arthritis of the hand, which caused the hand and wrist to swell

A newborn with gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum caused by a maternally transmitted gonococcal infection

Photomicrograph revealing the histopathology in an acute case of gonococcal urethritis using gram-stain technique

Partners (sex of partners, number of partners in prior 2 months/1 year)

Prevention of pregnancy - trying to conceive or contraceptive use

Protection from STIs/HIV - what does the patient do to protect him/herself from STIs and HIV?

Practices or types of sexual activities (oral/vaginal/anal and insertive/receptive), condom use

Past STIs/HIV - any prior diagnoses of STIs or HIV or viral hepatitis.

Physical exam

Inspection and palpation of the testis, epididymis, and spermatic cord should be performed. The penis shaft, glans, and meatus should also be examined and the presence of discharge assessed. A prostate exam is required if symptoms of prostatitis are present.

A swollen and/or tender testicle (usually one-sided) on palpation may indicate orchitis.

A swollen and/or tender epididymis on palpation may indicate epididymitis, which occurs in <5% of men with gonorrhea. [ 40 ] Unilateral testicular pain (without discharge or dysuria) and fever are also symptoms of epididymitis. [ 2 ]

The external genitalia (labia and clitoris) should be inspected before speculum exam of the cervix and vagina. It is recommended that lubricant jelly not be used as it can destroy Neisseria gonorrhoeae . Presence of mucopurulent or purulent exudate at the endocervix is looked for.

PID is the most important complication of gonorrhea in women. It may develop in up to one third of women with gonorrhea, and can lead to long-term sequelae even after resolution of infection. [ 41 ] [ 42 ] The most common sequelae of PID are chronic pelvic pain (40%), tubal infertility (10.8%), and ectopic pregnancy (9.1%). [ 43 ] [ 44 ] A bimanual exam for cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and adnexal tenderness is particularly important to assess possible ascending infection resulting in PID. Cervical motion tenderness is assessed using 1 or 2 fingertips to move the cervix and asking the patient if any pain results. Presence of a cervical mass suggests PID.

Bleeding that occurs with gentle passage of a cotton swab through the cervical os suggests cervical friability and cervicitis. [ 23 ]

Rectal gonorrhea may cause mucopurulent discharge from the anus.

The pharynx is examined for erythema and exudate. Image Anterior cervical lymphadenopathy may also be present. [ 2 ]

Gonococcal conjunctivitis can present with a thick white/yellow discharge. Examination of the eyes with a slit lamp is recommended so that infection of the cornea can be excluded.

Suspected disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI)

Pediatric gonococcal infection.

The most severe manifestations of pediatric gonococcal infection are ophthalmia neonatorum and sepsis, which can include arthritis and meningitis. Less severe manifestations include rhinitis, vaginitis, urethritis, and reinfection at site of fetal monitoring: for example, through scalp electrodes. Image

Infants at increased risk for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum are those who do not receive ophthalmia prophylaxis and those whose mothers have had no prenatal care, or have a history of STIs or substance misuse. [ 23 ] In the US, routine prophylactic eye drops are recommended for all newborns. [ 38 ] [ 46 ]

Sexual abuse is the most frequent cause of STIs (including gonococcal infection) in preadolescent children. [ 14 ] Anorectal and pharyngeal infection are common and frequently asymptomatic in sexually abused children. Vaginitis is the most common manifestation in preadolescent girls.

Laboratory evaluation: overview

Laboratory evaluation: men with urethral discharge, laboratory evaluation: men without urethral discharge, laboratory evaluation: women, laboratory evaluation: nongenital sites, laboratory evaluation: patients with suspected dgi, laboratory evaluation: infants with suspected gonococcal infection, laboratory evaluation for suspected gonococcal infection: children, adolescents, and adults with possible sexual assault, further investigations, age 20 to 24 years.

One of the strongest predictors of gonorrhea, with rates 4 to 5 times higher than the national average. According to US data, the highest rates in men and women are seen in the 20 to 24 years age group. [ 3 ]

men who have sex with men (MSM)

In the US, about one third of gonorrhea cases are reported in MSM. [ 3 ]

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's MSM Prevalence Monitoring Project in several urban STI clinics in the US showed high median site-specific positivity for rectal gonorrhea (15.9%) and pharyngeal gonorrhea (8.8%) among MSM. [ 24 ]

black ancestry

In the US, people of black ancestry have a rate that remains higher than other races/ethnicities and is between 8 and 9 times higher than the rate in white people (652.9 vs. 78.9 cases per 100,000). [ 3 ] There is no biologic basis for this; rate differences by race/ethnicity may represent contextual factors such as geography, socioeconomic status, and social structure that affect sexual networks. [ 25 ] In the US-based National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) study the highest rate among those ages 18 to 26 years was seen in black people (2.13%). [ 26 ]

current or prior history of STI

This is consistently found to be a risk factor for repeat infections and therefore is a clear indication for screening. [ 27 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] In the Add Health study (a US-based cohort study of adults ages 18 to 26 years), chlamydia was found as a coinfection in 69% of those with gonorrhea. [ 26 ] In this study most gonorrhea was asymptomatic, which may be because symptomatic people had received treatment. Women with prior bacterial vaginitis had a 26% increased risk of having gonorrhea. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with an increased risk of subsequent gonorrhea infection. [ 30 ]

multiple recent sex partners

The definition of multiple sex partners is variable, but 2 or more partners in the most recent 2 months is a commonly accepted definition. [ 29 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Working in the commercial sex industry qualifies as exposure to multiple partners.

inconsistent condom use

Sexual contact without a condom is a primary risk factor for gonorrhea infection. This includes any penetrative sex (usually referring to a penis) that involves a mucosa-lined orifice (oropharynx, vagina, and anus). [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ]

risk factors of partner

Unprotected sex is required for gonorrhea infection, but it does not constitute a high risk on its own if it is within a monogamous relationship. However, it is important to also consider the partner's risk factors because even if the patient has one partner, that partner may be linked to a high-risk sexual network by any of the same factors listed.

history of sexual or physical abuse

Reinfection of women with gonorrhea or chlamydia is associated with a history of physical or sexual abuse. [ 33 ]

substance use

Often linked to high-risk sexual networks and therefore in many circumstances can be reasonably considered a risk factor. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ]

past incarceration

Some studies have demonstrated that people with a history of imprisonment may have higher rates of STIs (including gonorrhea) than those with no history of imprisonment. [ 23 ] In the US, 4.4% of females and 1.2% of males entering a juvenile correctional institution in 2011 were positive for gonorrhea. [ 34 ]

high-morbidity community

It is always important to consider the local epidemiologic factors in a decision to screen a person. Within the context of a local outbreak of gonorrhea the threshold to initiate screening may be different.

Early symptom of gonorrhea.

Suggests epididymitis. This requires specialized treatment and needs to be distinguished from testicular torsion.

Mucopurulent cervicitis is the classical sign of gonorrhea infection in women but as a sign it is not common enough nor specific enough for the predictive value to be sufficient to make a diagnosis without supportive laboratory tests.

Physical findings include frank mucopus on swab and cervical os friability.

Considered for an STI and needs a bimanual exam. A significant number of women may have endometritis without overt symptoms. [ 41 ] If no overt pelvic pain is reported it also important to elicit whether pain occurs with sex.

Early symptom of gonorrhea usually followed by discharge hours to days later. [ 18 ]

The most common symptom of gonorrhea in men and will precede discharge.

Orchitis is usually one-sided.

Prostatitis is an uncommon finding with gonorrhea but is suspected if urinary obstructive symptoms or pelvic pain is present.

Associated with rectal gonorrhea infection.

Associated with rectal gonorrhea infection. Usually occurs with a bowel movement.

Associated with rectal gonorrhea infection. More common in men who have sex with men.

Women with gonorrhea may have some vaginal discharge, but lack of a discharge does not exclude infection.

In most vaginal discharges, other types of vaginitis such as trichomonas, yeast, and bacterial vaginosis predominate.

The discharge should be sent for microscopy. Leukorrhea is defined as >10 white blood cell count on high-power field of a vaginal fluid smear. [ 23 ]

Bleeding that occurs with gentle passage of a cotton swab through the cervical os suggest cervicitis. [ 23 ]

Tenderness suggests pelvic inflammatory disease, which requires specialized treatment.

The presence of a mass suggests pelvic inflammatory disease, which requires specialized treatment.

May be present in pharyngeal gonorrhea infection.

Gonococcal conjunctivitis presents with thick/white yellow discharge. Image

Can be seen with ascending gonorrhea infection or disseminated gonorrhea infection.

Indication of disseminated gonococcal infection. Image

Indication of disseminated gonococcal infection. Most commonly affected joints are wrists, ankles, and small joints of hands and feet. Image

Manifestation of gonococcal meningitis.

Manifestation of gonococcal endocarditis

Neonatal conjunctivitis. One of the most severe manifestations of pediatric gonococcal infection. Image

Less severe manifestation of pediatric gonococcal infection.

Most common manifestation of gonococcal infection in preadolescent girls. May occur in infants with gonococcal infection.

positive for gonorrhea

Nonculture testing using NAATs is generally considered the most robust method for testing, but clinicians should use the approved local diagnostic method. [ 23 ] [ 48 ] The Association of Public Health Laboratories and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend NAATs for the detection of genital tract infections with gonorrhea without routine repeat testing for positive results. [ 47 ] [ 50 ]

Useful for urine, urethral, cervical, and vaginal specimens. However, it is not Food and Drug Administration-approved for use in nongenital sites (pharyngeal and rectum). Individual laboratories can perform NAATs at nongenital sites if they satisfy regulations for Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments compliance before reporting results. [ 47 ] [ 50 ]

Most sensitive method to detect gonorrhea but has less than 100% specificity, particularly with pharyngeal and rectum specimens.

Samples for NAATs can be collected by the clinician/healthcare provider or the patient (self-collected). [ 23 ] [ 49 ] Self-collected specimens sent for NAATs have been found to be noninferior to clinician-collected specimens, although local laboratory validation of this collection method should be conducted. [ 51 ] [ 52 ]

A NAAT for chlamydial infection is also recommended. [ 23 ]

positive chocolate agar culture

Urethral, endocervical, rectal, pharyngeal, blood, synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, or conjunctival specimen can be used.

Definitive diagnostic test but has deficiencies in sensitivity with pharyngeal and rectal sites: sensitivity of culture for the pharynx is about 50%. [ 60 ]

It is the only available method to test for antimicrobial sensitivities.

Culture had been the only Food and Drug Administration-approved method for testing rectum and pharyngeal specimens, and it may be the only available option in some regions, but some NAAT platforms are now approved for these nongenital sites. [ 23 ]

Culture of swabs for chlamydial infection may also be requested.

positive leukocyte esterase

Useful if the patient has no urethral discharge.

Provides a presumptive diagnosis of urethritis and guides differential and further investigation. [ 23 ]

≥10 WBC per high-power field or ≥2 WBC per oil immersion field; intracellular gram-negative diplococci in polymorphonuclear leukocytes

Confirms urethritis and guides differential and further investigation.

Strongly suggests gonorrhea if organism seen. But does not rule out gonorrhea if organisms not seen. [ 61 ]

intracellular gram-negative diplococci in polymorphonuclear leukocytes

Confirms urethritis and guides differential and further investigation. Image

may be positive

Routine to rule out HIV. Time to HIV seropositivity with a third-generation enzyme immunoassay can be >21 days.

Routine to rule out syphilis. A Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test or serum rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test can take up to 3 months to become positive. Some laboratories may perform a reverse sequence screening algorithm that uses a serologic test before the RPR.

thickening of endometrium or tubes; fluid in the tubes or abscess

Highly specific for pelvic inflammatory disease. Useful in presence of chronic ascending infection resulting in tubo-ovarian abscess.

inflammatory changes of fallopian tubes and ovaries; abnormal fluid collection; thickened ligaments

Highly specific for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). When diagnosis of PID is uncertain or ultrasound is equivocal, either a CT or MRI may be performed, if available.

Chlamydia infection

Differentiating Signs/Symptoms

There are no history or physical exam features that can distinguish between chlamydia and gonorrhea infection except for disseminated infection, which is unique to gonorrhea.

Chlamydia is around 10 times more common than gonorrhea in young populations. [ 26 ] Chlamydia does not seem to be efficient at colonizing the pharynx and is less likely to be found there. In men having sex with men, Chlamydia is the most common cause of rectal infections. [ 58 ]

A specific form of genital ulcers and proctitis (lymphogranuloma venereum) is also caused by Chlamydia from a less common strain of Chlamydia trachomatis .

Differentiating Tests

The absence of diplococcus on microscopic exam with sufficient WBC for a diagnosis of urethritis is suggestive of chlamydia. Commercial nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) is usually a dual test combining both gonorrhea and chlamydia, therefore an ideal way to give a definite pathogenic diagnosis.

Diagnosis of chlamydia of the pharynx or rectum is by culture or with NAAT if available.

Diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum is suggested from high titers of chlamydial antibodies, NAAT positive for Chlamydia , and the typical clinical presentation.

Trichomonas

Trichomonas vaginalis is a common STI and is generally underreported. A survey of young Americans found an overall prevalence of 2.3%. [ 41 ] Common symptoms (e.g., vaginal discharge and itching) are not sufficient to distinguish gonorrhea from trichomonas.

T vaginalis is often diagnosed after failure of treatment for urethritis, in cases with negative tests for gonorrhea and Chlamydia .

Culture is the most efficacious test, but newer nucleic acid amplification tests are becoming available and will allow more rapid diagnosis. T vaginalis can be diagnosed by wet preparation from vaginal or urethral discharge but this technique has low sensitivity.

Other infectious causes of urethritis, cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and epididymitis

Other microorganisms, which are sexually transmitted but are not easily diagnosed, may cause both cervicitis and urethritis. These include atypical herpes simplex recurrences, Mycoplasma genitalium , and Ureaplasma urealyticum .

PID may also be caused by a mixture of organisms.

Epididymitis may be caused by enteric gram-negative organism, especially when there is a history of insertive anal sex. It may also occur in older men (≥35 years), usually resulting from bladder outlet obstruction.

There are no specific differentiating features between these other infectious agents and gonorrhea.

No commercial tests are available for M genitalium or U urealyticum .

Suggestive symptoms with a positive antibody test to herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2 and repeated negative test results for other etiologies suggests HSV infection.

Urinary culture of gram-negative organisms may be positive in cases of epididymitis.

Candidal vaginitis or bacterial vaginosis

Does not usually involve the upper genital tract and is caused by yeast species or a disruption in normal bacterial flora (bacterial vaginosis). These types of vaginitis are not sexually transmitted.

Presents as vaginal discharge, odor, and irritation.

Wet mount microscopic examination, cultures, or smears may show Candida .

In bacterial vaginosis, clue cells may be seen on wet mount and amine whiff test may be positive.

Urinary tract infection, female

Symptoms include dysuria, hematuria, and urgency. Left untreated the ascending infection may result in pyelonephritis with flank pain and fever.

Mid-stream urine culture positive for causative infectious agent.

Urinary tract infection, male

Nonpregnant women, pregnant women, treatment approach, uncomplicated gonococcal infection.

First-line treatment is a single dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone. [ 23 ] One meta-analysis found that ceftriaxone had better efficacy for uncomplicated gonorrhea compared with other antibiotics. [ 67 ] If chlamydial infection has not been excluded, patients should receive oral doxycycline for 7 days in addition to the cephalosporin. [ 23 ]

In patients with urogenital or anorectal gonorrhea who have a cephalosporin allergy, a single dose of intramuscular gentamicin plus oral azithromycin may be considered; however, gastrointestinal adverse effects may limit the use of this regimen. [ 23 ] In an asymptomatic person, a single dose of ciprofloxacin could be used if the provider is able to perform gyrase A (gyrA) testing to identify ciprofloxacin susceptibility (wild type). [ 23 ] [ 68 ] An infectious disease specialist should be consulted if there is known penicillin/cephalosporin allergy.