How To Create A Proactive Problem-Solving Culture? 10 Useful strategies

Last Updated: December 17, 2023 | by Paul Harstrom

How can one establish a proactive problem-solving culture? Before addressing this query, let us understand the rationale behind the need for such a culture in the first place.

Even the most well-established and reputable companies often face situations where customers express dissatisfaction by posting negative reviews about their products or services on social media.

Occasionally, companies respond to these complaints by offering apologies, refunds, or solutions, but only after the damage is already done. So, they kind of lost out this way. This reactive strategy can lead to potential customer dissatisfaction and harm the brand’s reputation.

Now imagine a company, where employees are actively monitoring customer feedback, analyzing trends, and identifying potential issues before they escalate. If they notice a pattern of dissatisfaction or receive early complaints, they take proactive measures.

This could involve reaching out to affected customers, implementing improvements to the product or service based on feedback, and communicating transparently about changes. By addressing concerns before they become widespread issues, the business maintains customer satisfaction, loyalty, and a positive brand image.

Hence, a reactive approach involves addressing complaints only after they have gained attention, potentially causing damage to the business’s reputation.

In contrast, a proactive approach to problem solving culture focuses on identifying and addressing customer concerns before they become critical, promoting a more efficient and resilient operation.

LEAD Diligently helps faith-driven executives gain clarity and wisdom to grow profitable enterprises. In this article, you are going to learn 10 useful strategies to create a proactive problem-solving culture so that you can enhance your organizational performance and grow profitably .

What Is A Proactive Problem-Solving Culture?

In the words of business visionary Peter Drucker:

“The best way to predict the future is to create it.” Peter Drucker

This ethos encapsulates the essence of a Proactive Problem-Solving Culture—an organizational mindset where potential challenges are addressed before they burgeon into critical issues, setting the stage for a company’s success.

In a proactive problem-solving culture, employees are encouraged to be forward-thinking and take the initiative to identify potential problems, analyze their root causes, and implement solutions. This approach contrasts with a reactive mindset, where actions are taken only after a problem has already occurred.

Building a proactive problem-solving culture involves creating an environment that values continuous improvement , open communication, and empowerment.

It encourages employees at all levels to think critically, share insights, and collaborate on innovative solutions. If you want to maximize the productivity of your employees click here to learn 5 scientifically proven ways to motivate and engage employees in the workplace .

How to Create a Proactive Problem-Solving Culture? (10 strategies):

Addressing issues in a company and solving problems effectively requires a systematic and proactive approach. Here’s a structured guide including 10 valuable strategies to create an effective problem-solving environment:

Acknowledge Issues:

Start by acknowledging and recognizing the existence of issues within the company. Utilize regular assessments, encourage open feedback, and monitor performance metrics diligently.

Categorize and Prioritize:

Categorize identified issues based on their nature, urgency, and impact on the organization. Prioritize them to focus on the most critical problems that need immediate attention.

Create an Issues List:

Establish an “issues list” to systematically track and document identified challenges. This list should be regularly reviewed and updated, providing a clear overview of ongoing issues. These can be challenges, opportunities, or unresolved matters.

Regularly revisit the issues list, assess the impact of implemented solutions, and refine strategies based on the evolving company’s demands.

Transition from Identification to Action:

Issues that are identified as potential company rocks , or priorities, but not immediately addressed as individual rocks should move to the issues list.

This list serves as a backlog of items that may require attention in the future . Decide when the right time is to address each issue.

Implement Structured Problem-Solving Sessions:

Conduct structured problem-solving sessions or meetings. These sessions should be action-oriented, focusing on finding solutions rather than dwelling on the problems.

Prioritize Implementation Over Discussion:

Emphasize the importance of implementing solutions rather than spending excessive time discussing issues. The goal is to move from identifying problems to actively resolving them.

Strategic Decision-Making with Deadlines:

Set specific timeframes for strategic decision-making through proactive problem management . It can be achieved by determining deadlines for resolving specific issues, such as making final decisions about new hires within 90 days.

Cultivate Individual Accountability:

Encourage a sense of individual accountability . Assign specific responsibilities to team members for addressing and resolving particular issues. Consider the concept of “individual rocks” as tasks or priorities individuals commit to.

Click here to learn 7 tips to create a culture of accountability in the workplace.

Integrate Future Planning:

Incorporate forward-looking planning into the problem-solving process. Consider future quarterly planning sessions where issues can be anticipated, and strategies can be developed to address them proactively.

Document and Analyze:

Document the entire problem-solving process, including the identified issues, proposed solutions, and the outcomes or plan for resolution. The goal is to prevent important matters from being forgotten and to have a structured approach to addressing them.

Concluding 10 Useful Strategies To Create A Proactive Problem-Solving Culture

10 Useful Strategies mentioned above help leaders Create A Proactive Problem Solving Culture in their companies. Adopting this structured approach not only addresses current issues but also anticipates and mitigates challenges in the future.

Did you find these strategies useful? Enlighten us with your thoughts in the comment section below!

Can you provide examples of companies that have successfully created a proactive problem-solving culture?

Many tech giants, such as Google and Microsoft, are known for promoting proactive problem-solving cultures. They encourage employees to engage in continuous improvement and innovation, encouraging them to address challenges before they escalate.

How does technology contribute to problem-solving in modern workplaces?

Technology plays a pivotal role by providing tools for data analysis, communication, and collaboration. Platforms like project management software , data analytics tools, and collaborative platforms enable teams to anticipate issues, share insights, and collectively address problems in real-time, contributing to a proactive work environment.

What steps can employees take individually to contribute to a proactive problem-solving culture within their teams or departments?

Employees can contribute by staying vigilant and identifying potential issues early on. Actively participating in team discussions, proposing effective solutions, and taking the initiative to address small problems before they arise are necessary steps.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Is Your Business Healthy and Fortified For Growth?

Take Our Assessment to Uncover Opportunities and Pinpoint Challenges

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Worry Impairs the Problem-Solving Process: Results from an Experimental Study

Sandra j. llera.

a Department of Psychology, Towson University, 8000 York Road, Towson, MD 21252.

Michelle G. Newman

b Department of Psychology, The Pennsylvania State University, 140 Moore Building, University Park, PA 16801.

Associated Data

Introduction:.

Many individuals believe that worry helps solve real-life problems. Some researchers also purport that nonpathological worry can aid problem solving. However, this is in contrast to evidence that worry impairs cognitive functioning.

This was the first study to empirically test the effects of a laboratory-based worry induction on problem-solving abilities.

Both high ( n = 96) and low ( n = 89) trait worriers described a current problem in their lives. They were then randomly assigned to contemplate their problem in a worrisome ( n = 60) or objective ( n = 63) manner or to engage in a diaphragmatic breathing task ( n = 62). All participants subsequently generated solutions and then selected their most effective solution. Next, they rated their confidence in the solution’s effectiveness, their likelihood to implement the solution, and their current anxiety/worry. Experimenters uninformed of condition also rated solution effectiveness.

The worry induction led to lower reported confidence in solutions for high trait worry participants, and lower experimenter-rated effectiveness of solutions for all participants, relative to objective thinking. Further, state worry predicted less reported intention to implement solutions, while controlling for trait worry. Finally, worrying about the problem led to more elevated worry and anxiety after solving the problem compared to the other two conditions.

CONCLUSIONS:

Overall, the worry induction impaired problem solving on multiple levels, and this was true for both high and low trait worriers.

Worry is the defining feature of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ), but it is also a common experience for most individuals. Though many report the belief that worry has benefits for coping with potential threats ( Borkovec & Roemer, 1995 ; Hebert, Dugas, Tulloch, & Holowka, 2014 ), a wide literature documents its negative impact on cognitive, emotional, and behavioral levels. Despite being extensively researched, the effects of worry on some aspects of cognitive functioning and behavioral motivation remain understudied and require further exploration.

Several theories suggest that worry negatively affects cognitive functioning. The Attentional Control Theory ( Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, 2007 ), posits that worry demands attentional resources that could be allocated to other cognitive capacities and thus creates cognitive impairment. Similarly, Affective Neuroscience theories propose that worry increases cognitive load and interferes with the capacity to ignore task-irrelevant matters ( Beaudreau, MacKay-Brandt, & Reynolds, 2013 ). These theories further posit that because worrisome thoughts are attentionally demanding, additional resources are required to inhibit worry in order to focus attention elsewhere. Thus, worry may interfere with tasks that compete for executive functioning resources.

This perspective has garnered empirical support. High trait worriers performed slower than controls on a number of cognitive and decision-making tasks, in both clinical ( LaFreniere & Newman, 2019 ; Stefanopoulou, Hirsch, Hayes, Adlam, & Coker, 2014 ) and non-clinical ( Tallis, Eysenck, & Mathews, 1991 ) samples. In a meta-analysis of 94 studies, recurrent negative thinking, including trait worry, was associated with impaired ability to discard irrelevant information from working memory ( Zetsche, Bürkner, & Schulze, 2018 ). Additionally, impaired cognitive functioning, such as difficulty concentrating, slowed learning, and delayed decision-making, has been associated with GAD status in both undergraduate ( LaFreniere & Newman, 2019 ; Pawluk & Koerner, 2013 ) and community GAD samples ( Hallion, Steinman, & Kusmierski, 2018 ). Similar to trait-level worry, experimentally manipulated state worry has also been found to reduce working memory ( Rapee, 1993 ; Trezise & Reeve, 2016 ) and attentional control ( Hayes, Hirsch, & Mathews, 2008 ; Stefanopoulou et al., 2014 ). Further, efforts to inhibit state worry depleted working memory and performance on cognitive tasks ( Hallion, Ruscio, & Jha, 2014 ). Thus, both trait and state worry independently have been associated with cognitive impairment.

Similar to evidence of the association between trait/state worry and impaired cognitive functioning, there have been questions as to whether worry impacts problem-solving abilities. D’Zurilla and Goldfried (1971) suggest that effective problem-solving requires five major components. These include: 1) problem orientation (i.e., confidence in and perceived control over the problem-solving process), 2) problem definition and goal identification, 3) generating solutions, 4) decision making, and 5) implementation/verification. Accordingly, impairment at any one of these levels would hinder one’s ability to resolve problems.

On the one hand, many individuals, especially those with GAD symptoms, believe that worry is helpful when solving problems. In fact, such beliefs predicted worry severity levels ( Hebert et al., 2014 ), and were able to distinguish those with GAD from controls ( Borkovec & Roemer, 1995 ). Further, beliefs that worry was helpful in the face of problems, or that persistent thinking was required in order to find the best solution, both predicted trait worry levels ( Kelly & Kelly, 2007 ; Sugiura, 2007 ). In fact, when tested on their ability to solve hypothetical problems in a laboratory setting, anxious participants performed no differently than controls ( Anderson, Goddard, & Powell, 2009 ), and in an unselected student sample these abilities were uncorrelated with trait worry ( Davey, 1994 ).

On the other hand, however, there is reason to believe that the act of worrying and/or trait worry might be associated with impairment in the real world. Negative effects of worry on problem-solving could happen in several ways. Worrying about a problem could increase cognitive load ( Beaudreau, MacKay-Brandt, & Reynolds, 2013 ), interfering with one’s ability to focus on effective solution generation. This could induce lower confidence in one’s abilities to generate effective solutions, leading individuals to stall or avoid decision-making ( D’Zurilla & Goldfried, 1971 ) or to prematurely dismiss possible solutions as likely to be ineffective. Additionally, worry could provoke repetitive rehearsal of the problem and/or focus on potential negative outcomes ( Mathews, 1990 ), thereby interfering with effective solution generation and implementation. Trait worry could also have negative effects. These could include difficulty tolerating the uncertainty inherent in the problem-solving process ( Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, & Freeston, 1998 ), which might be linked to the higher “evidence requirements” seen in chronic worriers when making decisions ( Tallis et al., 1991 ). This, in addition to heightened attentional bias toward threat ( Goodwin, Yiend and Hirsch, 2017 ), could serve to prolong indecision in the face of real-life problems while the worrier attempts to gather more information. Finally, the Contrast Avoidance model of GAD ( Newman & Llera, 2011 ) would suggest that for chronic worriers, reluctance to implement solutions could be due to a fear of getting one’s hopes up only to be confronted with failure (i.e., emotional contrast). In fact, it is possible that multiple factors could work together to impair problem-solving abilities.

In support of impairment related to chronic worry, Davey, Hampton, Farrell, and Davidson (1992) identified a link between harboring a negative attitude toward problems, termed negative problem orientation (NPO), and high trait worry. Since then, NPO has been linked with anxiety and trait worry in both clinical ( Dugas et al., 1998 ; Fergus, Valentiner, Wu, & McGrath, 2015 ; Ladouceur, Blais, Freeston, & Dugas, 1998 ) and non-clinical samples ( Anderson et al., 2009 ; Robichaud & Dugas, 2005 ). Notably, NPO was more robustly associated with trait worry over other anxiety, mood, and obsessive symptoms in a mixed-clinical sample ( Fergus et al., 2015 ). Additional studies found trait worry to be associated with impairment in other aspects of the problem-solving process, such as skills and/or knowledge base. For example, Borkovec (1985) observed that whereas chronic worriers were very good at defining their problems and identifying possible negative outcomes, they often had difficulty implementing solutions. Further, when assessing real-life problem solving based on daily diary and recall data, a mixed anxious-depressed group demonstrated fewer functional cognitions and behaviors, and less effective solutions, than did controls ( Anderson et al., 2009 ).

Although such research on the nature of chronic worriers tends to converge, the extent to which the act of worrying itself impairs problem solving represents a point of contention within the field. Some researchers have argued that worry interferes with successful problem resolution across the board, whereas others contend that this may only apply to pathological worriers (i.e., those for whom worry is excessive and uncontrollable). Mathews (1990) adopted the first stance, arguing that although worry may begin as attempted problem solving, it predominantly leads to the cognitive rehearsal of danger for everyone. Taking the second stance, Davey and colleagues ( Davey, 1994 ; Davey et al., 1992 ) proposed that worry may actually enhance problem solving for many individuals, but that this process can become thwarted for those with high levels of trait worry. The latter argument was based in part on evidence that trait worry was associated with some active coping styles (e.g., information seeking) when controlling for trait anxiety in unselected student samples ( Davey et al., 1992 ). Therefore, Davey and colleagues concluded that for some individuals worry might be an adaptive or constructive approach when confronting a problem.

Nonetheless, an abundance of data shows that worry increases state negative affect and arousal for all individuals (see Newman & Llera, 2011 ; Newman et al., 2019 ; Ottaviani et al., 2016 ), which itself may impact the problem-solving process. For instance, a negative mood induction increased perseveration and catastrophizing on a high-responsibility task ( Startup & Davey, 2003 ), which could have negative implications for problem solving. Furthermore, daily diary studies have found that the intensity of state worry was associated with more anticipation of negative outcomes, greater negative evaluation of solutions to problems, more self-blame, and lower rates of solution selection during worry episodes, in samples including both high and low trait worriers ( Szabó & Lovibond, 2002 , 2006 ). Additionally, state levels of anxious thinking, including worry, were associated with lower problem-solving effectiveness in a community GAD sample ( Pawluk, Koerner, Tallon, & Antony, 2017 ).

In summary, although there is strong evidence to suggest that worry is associated with impairment in problem solving, none of the studies reviewed above experimentally manipulated worry when testing problem-solving abilities. Therefore, it is impossible to determine the extent to which worry itself causally impacted the problem-solving process, as opposed to other characteristics associated with state or trait worry. Interestingly, depressive rumination (a close conceptual relative to worry) has been shown to impact both mood and the problem-solving process across several studies. For example, experimentally induced rumination (versus distraction) led to lower mood in a non-clinical dysphoric sample, and resulted in generating less effective solutions for hypothetical problems, as well as reduced likelihood of implementing solutions for a personal problem ( Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995 ; Lyubomirsky, Tucker, Caldwell, & Berg, 1999 ). The absence of similar research on the effect of worry represents a critical gap in our understanding of this phenomenon.

In this study, we sought to address this gap by testing the effects of experimentally manipulated worry on problem solving using a sample of individuals with both high and low trait worry. In this way, we were able to test whether inducing state worry would hinder problem solving for all participants, thereby supporting Matthews’ (1990) perspective, or if it would enhance problem-solving in low trait worriers and only become problematic at high trait levels, thus supporting Davey and colleagues’ perspective ( Davey, 1994 ; Davey et al., 1992 ). We chose to observe the effects of worrying about a real-life problem, as opposed to a hypothetical problem, in order to increase external validity. As a comparison condition, we chose the problem definition stage of problem solving as outlined in D’Zurilla and Goldfried (1971) . This allowed us to equalize the amount of time spent contemplating the problem, but to channel thinking into styles typical of a worry episode versus thinking in a more objective, emotionally neutral manner. As an additional control condition, a third group engaged in a diaphragmatic breathing task. Immediately afterward, all groups were instructed to brainstorm solutions to their problem and choose the solution they thought would be most successful. We tested a variety of outcomes related to problem solving, including the number of solutions generated, self-reported and experimenter-rated effectiveness of solutions, as well as participant ratings of intention to implement solutions. Further, we assessed state levels of anxiety and worry following the solution-generation phase, to determine the extent to which participants felt calmer once a solution had been identified.

We hypothesized that relative to objective thinking or diaphragmatic breathing instructions, worrying about a problem would lead to 1) generating fewer solutions during brainstorming, 2) generating less effective solutions (based on both participants’ and judge’s ratings), and 3) lower intention to implement solutions. Further, we hypothesized that 4) worrying would lead to lingering anxiety and worry following solution generation, relative to other conditions. We also hypothesized that these effects would be observed for both high and low trait worriers alike.

Research Design and Method

Overall design.

A 2 (Group: High vs. Low Trait Worry) X 3 (Condition: Worry, Think Objectively, Diaphragmatic Breathing) block design was used to determine the effects of worrying about a problem on various outcomes related to problem-solving.

Participants and Measures

The current study recruited 185 volunteers from psychology courses in a public university. Students received class credit as compensation. Participants were largely young adult (M = 20.06 years, SD = 6.47) females (76.8%), with 57.8% identifying as White, 24.3% African American, 7.6% Asian, 6.2% Hispanic/Latinx, 1% American Indian/Pacific Islander, and 8.6% other (e.g., “mixed race”).

Participants were selected based on their scores on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990 ), a 16-item self-report measure designed to assess the frequency, intensity, and uncontrollability characteristics of trait worry. The PSWQ demonstrates strong internal consistency (Chronbach’s α = .91; Meyer et al., 1990 ) and retest reliability (.74 – .93; Molina & Borkovec, 1994 ). Internal consistency for the current sample was high (α = .95). Participants also completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-Q-IV; Newman et al., 2002 ) to assess for clinical-level GAD symptoms. The GAD-Q-IV is a 9-item self-report questionnaire based on diagnostic criteria for GAD. It demonstrates strong internal consistency (α = .94) and good retest reliability. A cut-score of 5.7 leads to 83% sensitivity and 89% specificity relative to a structured diagnostic interview ( Newman et al., 2002 ). Internal consistency for the current sample was high (α = .91).

Participants were included in the High Trait Worry group (N = 96) if they scored in the upper range on the PSWQ (≥ 60) during a pre-screen. On the day of testing, the High Trait Worry PSWQ score mean was comparable to that found in GAD patient samples (M = 66.68, SD = 9.47; see Startup & Erickson, 2006 ). The High Trait Worry mean on the GAD-Q-IV was also well above the clinical cut-score (M = 8.58, SD = 2.35). Participants were included in the Low Trait Worry group (N = 89) if they scored in the mid-low range on the PSWQ (≤ 45). On the day of testing, scores in this group were comparable to those of nonanxious samples from other studies (M = 41.02, SD = 11.93; see Startup & Erickson, 2006 ). Further, the Low Trait Worry group scored well below the cut-score on the GAD-Q-IV (M = 3.66, SD = 2.82).

This study was approved by the university IRB. Participants were each tested alone in a private room equipped with a computer. All instructions and tasks were completed using the Qualtrics survey platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants first provided informed consent, and then completed demographic questions along with the PSWQ and GAD-Q-IV. Next, they completed baseline state measures, comprised of 4 items: worry , anxiety , relaxation , and mood . They were instructed to rate each item based on how they felt right now . The first 3 items were rated on a scale of 0 ( not at all ) to 100 ( extremely ). Mood was rated from 0 ( very negative ) to 100 ( very positive ).

Participants were next instructed to identify a current, real-life problem; specifically, one that was affecting them right now, and for which they had some control over the outcome. The latter requirement was to assist in identifying a problem for which there were possible solutions, as opposed to an uncontrollable issue (e.g., a loved one’s terminal illness). They were then asked to briefly describe their problem by typing it out on the computer.

Next, participants were randomly assigned to either a Worry (WOR; N = 60) or Think Objectively (T-OBJ; N = 63) task, with the remaining third assigned to a Diaphragmatic Breathing (DB; N = 62) task. The primary distinction between WOR and T-OBJ conditions was that participants either worried or did not worry over their problem. To that end, instructions for the WOR task were based on the definition of worry as negatively valanced cognitive activity focused on a threat, along with consideration of potential negative outcomes (i.e., negative emotional and catastrophic thinking; Borkovec, 1985 ; Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinsky, & DePree, 1983 ). Those in the WOR task were therefore instructed to worry about their problem, with an emphasis on their concerns along with possible negative outcomes and implications (see supplement for full instructions ). To control for the amount of time spent contemplating the problem, but to do so in a non-emotional, non-catastrophic manner, instructions for the T-OBJ task were based on the problem definition stage of problem solving ( D’Zurilla & Goldfried, 1971 ). Participants in the T-OBJ task were instructed to attempt to focus on their problem in a more objective, emotionally neutral manner, such as by breaking it down into smaller components and coming up with ultimate goals. If they found themselves focusing on negative thoughts, participants were instructed to refocus their attention back on the problem itself.

After receiving these instructions, participants in the WOR and T-OBJ conditions were asked to think about their problem for 2 minutes in the specified manner. Those in the DB task were given instructions to engage in diaphragmatic breathing for 2 minutes.

Following this task, and to determine whether the manipulations had their intended effects, all participants again completed state measures of worry , anxiety , relaxation , and mood . This was to ensure that conditions led to three distinct groups: one that had engaged in emotional/catastrophic thinking (WOR), one that had engaged in non-emotional, non-catastrophic thinking (T-OBJ), and one that had engaged in a relaxation-inducing breathing task (DB). As such, distinctions on state levels of worry , anxiety , relaxation , and mood between conditions served as compliance checks for adherence to the manipulations.

Immediately afterward, all participants were asked to generate as many solutions to their problem as they could for 2 minutes, representing the brainstorming stage of problem solving. Solutions were typed out on the computer. Next, they were instructed to reflect on these ideas and choose their “best, most effective” solution, representing the decision-making stage. Once finished, they ranked how confident they felt that this solution would be effective, as well as how likely they were to actually carry it out, on a scale of 0 ( not at all confident/likely ) to 100 ( very confident/likely ). They then provided final ratings of current state worry and anxiety and were debriefed about the study.

Once data collection was complete, a judge uninformed of condition rated participants’ self-identified “best” solutions for their effectiveness on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all effective , to 7 = extremely effective ), identical to that used in similar studies ( Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995 ; Lyubomirsky et al., 1999 ). To determine this score, they rated the likelihood that participants’ solutions would lead to successful resolution of the problem (i.e., maximize positive consequences and minimize negative ones, and not create additional problems; D’Zurilla & Goldfried, 1971 ). For example, if participants listed a solution that would likely improve or resolve the situation (e.g., behavior that would directly enhance their performance in a class, etc.), that was rated as more effective. If their solution was unlikely to improve or resolve the situation, or could potentially exacerbate the issue (e.g., distraction from or avoidance of the problem, etc.), it would be rated as less effective. A second independent judge who was also uninformed of condition rated a random selection of 25% of responses, with evidence of sufficient interrater reliability (ICC = .7). (See Supplemental Materials for an overview of the process used to ensure reliability of judges’ ratings.)

Data Analytic Plan

We first tested whether there were any differences at baseline on measures of state worry , anxiety , relaxation , and mood , using a 2 (Group: High/Low Trait Worry) X 3 (Condition: WOR, T-OBJ, DB) MANOVA. Next, to test that WOR, T-OBJ, and DB tasks had the intended effects, we ran a similar MANOVA but with ratings of state measures of worry , anxiety , relaxation , and mood immediately following the induction as manipulation checks.

To test the 4 main hypotheses, we ran a series of factorial ANOVAs, using Group and Condition as predictors. Outcome variables included 1) the number of solutions participants generated during the brainstorming phase, 2) participant and judge’s ratings of effectiveness of solutions, and 3) ratings of intention to implement solutions. Finally, to determine the presence of any lingering anxiety and worry after participants chose their best solution (4), we ran a MANOVA with Group and Condition as predictors, and state worry and anxiety levels after identifying “best” solutions as outcomes.

In the case of nonsignificant findings, we ran exploratory secondary analyses in the form of hierarchical linear regression models to test if reported state worry levels following the WOR/T-OBJ/DB tasks could predict problem-solving outcomes, while controlling for trait worry. The purpose of these analyses was to determine if the extent to which participants reported actually worrying during the induction would be a better predictor than their assigned condition, while also controlling for the possible influence of trait worry on these outcomes. To do so, we entered PSWQ in the first block of the model, followed by state worry levels in the second block. To address any issues of non-normality, bootstrapping using 1000 samples was applied to all ANOVAs and regressions.

Baseline Measures and Manipulation Check

At baseline, there was a main effect of Group, F (4, 176) = 15.92, p < .001, η 2 p = .27. As expected, the High Trait Worry group reported more baseline worry and anxiety than did the Low Trait Worry group. Further, the Low Trait Worry group reported more baseline relaxation and better mood than did the High Trait Worry group (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations). There was no main effect of Condition; F (8, 354) = 1.55, p = .139, η 2 p = .03; and no Group X Condition interaction; F (8, 354) = 1.07, p = .385, η 2 p = .02; suggesting no significant baseline differences between conditions.

State Measures at Baseline and Post Problem-Thinking Task

Note . Reported raw means with standard deviations in parentheses. WOR/W = worry task, T-OBJ/O = think objectively task, DB = diaphragmatic breathing task, ns = non-significant.

Following the WOR, T-OBJ, and DB tasks, our manipulation check measures showed a main effect of Group, F (4, 176) = 15.07, p < .001, η 2 p = .26. The High Trait Worry group reported significantly more worry and anxiety , lower relaxation , and worse mood than the Low Trait Worry group, regardless of their assigned task. More importantly, however, there was a main effect of Condition; F (8, 354) = 8.75, p < .001, η 2 p = .17; such that WOR led to significantly higher ratings of worry and anxiety than T-OBJ and DB, and T-OBJ led to higher ratings than DB. WOR also led to significantly worse mood than both T-OBJ and DB, which were not significantly different from one-another. Finally, DB led to significantly higher relaxation than both T-OBJ and WOR, and T-OBJ was higher than WOR (see Table 1 ). There was no significant Group X Condition interaction, F (8, 354) = .93, p = .494, η 2 p = .02. As such, data suggest that these tasks operated in the intended way for both High and Low Trait Worry groups.

Main Hypotheses

Number of solutions..

Contrary to predictions, there were no main effects of Group; F (1, 178) = .67, p = .414, η 2 p = .00; or Condition; F (2, 178) = 2.61, p = .076, η 2 p = .03; and no interaction; F (2, 178) = .87, p = .419, η 2 p = .01; on number of solutions generated during the brainstorming period. In a follow-up regression, the first block of the model, consisting of the PSWQ, was not significant; F (1,181) = .17, p = .685; and accounted for only 0.1% of the total variance. Adding state worry levels to the model did not significantly increase predictive value; F (1,180) = 1.52, p = .221; and only accounted for an additional 1.6% of the variance.

Effectiveness of solutions.

In terms of participants’ own ratings of their confidence in solution effectiveness, there was a main effect of Group; F (1, 178) = 9.13, p = .003, η 2 p = .05. Overall, High Trait Worriers reported less confidence in the effectiveness of their solutions (M = 66.73, SD = 22.31) than did Low Trait Worriers (M = 76.25, SD = 23.57), regardless of condition. There was no main effect of Condition; F (2, 178) = 1.01, p = .367, η 2 p = .01; but there was a significant Group X Condition interaction; F (2, 178) = 4.54, p = .012, η 2 p = .05. When divided by Group, High Trait Worriers in the WOR condition rated confidence in their selected solution as significantly lower (M = 57.77, SD = 29.46) than those in T-OBJ (M = 72.97, SD = 15.0; p = .017), and marginally lower than those in DB (M = 68.97, SD = 18.06; p = .076), but this did not reach significance. There were no significant differences between T-OBJ and DB ( p = .347; see Figure 1 ). Low Trait Worriers did not demonstrate significant differences by condition (all p ’s > .05).

Participant Ratings of Confidence in Effectiveness of Solutions for the High Trait Worry Group

Note. WOR = worry task, T-OBJ = think objectively task, DB = diaphragmatic breathing task, * p < .05.

In terms of judge’s ratings, there was a main effect of Condition; F (2, 177) = 5.08, p = .007, η 2 p = .05. Those in the T-OBJ condition were judged to have generated significantly more effective solutions (M = 5.77, SD = .93) than those in WOR (M = 5.18, SD = 1.19, p = .004) and DB (M = 5.21, SD = 1.38, p = .009), which were not significantly different from each other ( p = .938). Observed differences were modest, but nonetheless significant (see Figure 2 ). There was neither a main effect of Group; F (1, 177) = .14, p = .711, η 2 p = .001; nor an interaction; F (2, 177) = 1.85, p = .161, η 2 p = .02.

Judge’s Ratings of Effectiveness of Solutions across High and Low Trait Worry Groups

Note. WOR = worry task, T-OBJ = think objectively task, DB = diaphragmatic breathing task, ** p < .01.

Intention to implement solutions.

Contrary to predictions, there were no main effects of Group; F (1, 178) = 3.00, p = .085, η 2 p = .02; Condition; F (2, 178) = .21, p = .814, η 2 p = .00; or an interaction; F (2, 178) = 2.34, p = .10, η 2 p = .03; on participants’ ratings of intention to implement their solutions. A follow-up regression indicated that trait and state worry together significantly predicted intention, accounting for 5.5% of the total variance. When entered first, the PSWQ was a negative predictor of intention ( β = −.158, p = .032), such that higher trait worry predicted less reported intention. Upon adding state worry levels, the model’s predictive value significantly increased (Δ R 2 = .03, p = .017). Higher state worry also predicted less reported intention to implement solutions ( β = −.212, p = .020), but importantly, trait worry was no longer a significant predictor in the full model (see Table 2 ).

Trait and State Worry Predicting Intention to Implement Solutions

Note. Confidence intervals and standard errors are based on 1000 bootstrapped samples. PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire, Worry = self-reported state worry levels post problem-thinking task,

Worry and anxiety levels after choosing a solution.

There was a main effect of Group; F (2, 178) = 18.17, p < .001, η 2 p = .17. On average, High Trait Worriers reported greater worry (M = 40.53, SD = 26.04) and anxiety (M = 42.80, SD = 25.97) than did Low Trait Worriers (M = 21.91, SD = 26.59; M = 21.12, SD = 25.11, respectively) after generating their solutions, regardless of condition. Consistent with hypotheses, there was also a main effect of Condition; F (4, 358) = 4.27, p = .002, η 2 p = .05. All participants in the WOR condition reported significantly greater worry (M = 40.82, SD = 29.68) and anxiety (M = 41.90, SD = 29.40) following solution generation compared to those in T-OBJ (M = 31.10, SD = 25.55, p = .047; M = 32.11, SD = 27.69, p = .030; respectively) and DB (M = 23.11, SD = 25.80, p = .002; M = 23.42, SD = 23.01, p < .001; respectively). Those in the T-OBJ condition also reported greater anxiety than those in DB ( p = .042), but not greater worry ( p = .071; see Figure 3 ). There was no Group X Condition interaction; F (4, 358) = .87, p = .484, η 2 p = .01.

Post-Solution Generation State Levels

Note. WOR = worry task, T-OBJ = think objectively task, DB = diaphragmatic breathing task, * p < .05, ** p < .01

Research has long suggested the possibility of a connection between worry and impaired problem solving; yet no prior study has experimentally manipulated worry to test for a causal link. In this study we tested the effects of a controlled worry manipulation on several factors related to the problem-solving process, using both high and low trait worriers. Ultimately, we found that worrying about a real-life problem, relative to attempting to think about the problem objectively or diaphragmatic breathing, led to interference at multiple levels of problem solving. These findings held true at least in part for both high and low trait worriers alike.

Several findings emerged in terms of the effects of trait or state worry on aspects of the problem solving process. Contrary to our expectations, we found no differences for Group or Condition on the number of solutions participants generated when asked to brainstorm ways to solve their problems. This is not to say that all solutions were of equal quality. For example, some participants listed ideas such as, “ignore it until later”, “get some sushi”, and “do nothing”, alongside more effective ideas (e.g., “join a study group”, “make a budget and stick to it”). Listing as many ideas as possible without judgment while in the brainstorming phase is considered beneficial for problem solving ( D’Zurilla & Goldfried, 1971 ). Our data suggested that both trait worry status and condition type neither significantly helped nor hindered brainstorming performance, and that specific negative effects of worry only emerged later in the problem-solving process.

After choosing the “best” of these solutions, however, high trait worriers reported lower confidence in the effectiveness of their chosen solution compared to low trait worriers, regardless of condition. Also, high trait worriers who worried before generating solutions reported significantly lower confidence in their chosen solution than did those instructed to think about their problems more objectively. They also reported marginally lower confidence than those who engaged in a diaphragmatic breathing exercise, though this did not reach significance. This is consistent with prior findings that chronic worriers reported lower confidence in their ability to solve problems relative to nonanxious controls (e.g., Anderson et al., 2009 ; Ladouceur et al., 1998 ); however, this is the first study to demonstrate that in high trait worriers, the specific act of worrying reduced problem-solving confidence. In low trait worriers, on the other hand, worry (vs other conditions) did not lead to a significantly different impact on confidence in their solutions’ effectiveness.

The fact that a prior worry induction only reduced confidence for chronic worriers is more in line with the perspective articulated by Davey and colleagues ( Davey, 1994 ; Davey et al., 1992 ), who argued that factors such as low problem-solving confidence would impair problem solving, but only for pathological worriers. Notably, high trait worriers who were instructed to think objectively reported mean confidence scores that were significantly higher than those instructed to worry. These results imply that instructing chronic worriers to think about their problems in a more objective manner, and to refrain from negative thinking, may counteract such pessimistic beliefs and enhance confidence levels. However, contrary to Davey’s theory, there was no significant benefit of worry on confidence in low trait worriers. Thus, whereas the worry induction impaired confidence in high trait worriers, it neither helped nor hindered confidence in low trait worriers.

As opposed to participants’ subjective ratings of confidence in their solutions’ effectiveness, ratings made by an independent judge reflected our attempts to objectively rate whether the solution would be effective. In this case, a main effect of condition emerged across all participants. According to these ratings, attempting to think objectively about a problem led to a small but significant advantage in coming up with more effective solutions relative to both worrying and diaphragmatic breathing, which were not significantly different. As such, this finding does not represent a unique impairment effect of worry per se , but rather points to the benefits of attempting to contemplate problems in an objective, emotionally-neutral manner. It also indicates that although worrying did not reduce low trait worriers’ confidence in their solution effectiveness, such confidence was not matched by an independent judge.

To further unpack this finding, as a non-worry comparison individuals in the T-OBJ condition were instructed to think about their problem in a less emotional, more constructive way (i.e., breaking it down, focusing on their goals), without falling into negative or catastrophic thinking. We cannot rule out that this may have fueled more solution-focused thinking than worrying. In fact, the very act of focusing on a problem (whether it be catastrophically or objectively), likely made it difficult for participants not to consider various possible solutions during this manipulation period. If, however, those in the T-OBJ condition tended to naturally spend more time generating better solutions, this still supports the conclusion that worry detracts from problem solving, as it suggests that the negative and catastrophic thinking characteristic of worry interferes with more constructive processes and ultimately detracts from coming up with good solutions. It also suggests this can happen for both high and low trait worriers.

Regarding the lack of differences between WOR and DB on experimenter-rated effectiveness, it is important to note that those randomly assigned to the DB condition were not instructed to contemplate their problem at all prior to brainstorming solutions, but rather were instructed to focus attention on their breathing. That they were then able to generate impromptu solutions rated as not different from solutions of those who had actively worried over their problem beforehand, is a notable finding. This suggests that worrying about a problem offered no greater advantage in this context than did a diaphragmatic breathing exercise. It also contradicts the beliefs of many individuals, and especially those of chronic worriers, that worrying is necessary in order to find the best solution to a problem (e.g., Borkovec & Roemer, 1995 ; Hebert et al., 2014 ). Taken together, these findings are more consistent with Mathews’ (1990) proposition that for all individuals, the act of worrying is not actually helpful in terms of finding adequate solutions to problems.

In terms of participants’ reported intention to implement their solutions, there were no significant effects of Group or Condition. A follow-up exploratory regression analysis identified that the extent to which participants worried during their assigned task (irrespective of what that task was) predicted lower reported intention to engage in proactive action. This effect was not simply driven by those with higher trait worry, as state worry predicted ratings of intention when controlling for trait worry, and trait worry was no longer a significant predictor once state worry was entered in the model. This finding provides more clear support for Mathews’ (1990) stance on worry thwarting the problem-solving process, regardless of whether it is experienced at chronic levels or not. This also dovetails with the finding that depressive rumination reduced participants’ reported likelihood to implement solutions to their problems ( Lyubomirsky et al., 1999 ), suggesting that both forms of repetitive negative thinking may discourage engaging in such proactive behaviors. However, it should be noted that this analysis was simply a secondary, and more correlational, exploration of our data, and as such does not allow for more robust causal interpretations.

Finally, we found that for both high and low trait worriers, worrying about one’s problem led to significantly higher reported worry and anxiety levels even after having identified a solution, as compared to thinking objectively about the problem or relaxing. This is consistent with research showing that the negative effects of worry linger over time (e.g., Newman et al., 2019 ; Pieper, Brosschot, van der Leeden, & Thayer, 2010 ), and appears to hold true even after making a decision about the best course of action to ameliorate a problem. Thus, rather than feel a sense of resolution about the issue, with corresponding decreases in worry and anxiety, worrying before choosing a solution may instead lead to lingering feelings of doubt.

Overall, these results provide evidence that engaging in worry is detrimental to problem solving on multiple levels, which apart from reducing confidence in the process, appears to affect both high and low trait worriers alike. One explanation for these findings may be that, consistent with Attentional Control Theory ( Eysenck et al., 2007 ), worrying about a personal problem focused participants’ attention on threatening aspects of the situation (e.g., potential negative outcomes). As such, shifting from worrying into generating and evaluating solutions to the problem, (i.e., threat-related versus goal-directed attention) demanded additional cognitive resources. Attempting to think about the problem objectively, however, is more consistent with goal-directed attention and thus would not have required inhibition. In this way, attempting to think objectively may have allowed for greater access to cognitive resources while problem solving, and possibly more time spent contemplating solutions, relative to worrying. However, we did not measure these effects directly, other than to show that objective thinking facilitated generating more highly rated solution effectiveness than either worry or a breathing exercise.

Another explanation may be that the worry induction both increased cognitive load, and led to greater anxiety and worse mood, and these factors interacted to undermine the problem-solving process. According to Gray’s (1990) neuropsychology theory of emotions, anxiety triggers the behavioral inhibition system, promoting harm-avoidance over approach strategies in the face of a problem. This dovetails with the affect-as-information perspective, which states that affect influences judgment and decision-making ( Clore & Huntsinger, 2007 ). As such, in the context of problem solving, a negative mood may focus attention on potential obstacles to goals or unwanted outcomes, thus leading to pessimistic appraisals of one’s performance (see Schwarz & Skurnik, 2003 ). Our data support this trajectory based on the fact that worry 1) created greater negative affect in the moment, 2) led to sustained worry and anxiety levels even after participants had chosen a solution, 3) decreased confidence in effectiveness of solutions for the high worry group, 4) led to lower judge’s ratings of effectiveness, and 5) predicted less intention to implement solutions for all participants, while controlling for trait worry (though this latter finding was more correlational than causal). In sum, this suggests that worry led to negative cognitive and emotional effects, impairing problem solving at several stages of the process.

Overall, although the worry induction reduced problem-solving confidence only for high trait worriers, it led to a number of additional negative outcomes for all participants. As such, these data provide initial evidence that state worry hinders proactive problem solving across high and low trait worry levels. Moreover, despite the fact that low trait worriers reported a non-significant impact of worry on their confidence in solutions, it still predicted lower judge’s ratings of the solution effectiveness and less willingness to enact them. Therefore, results of this study provide more robust support for Mathews’ (1990) theory, suggesting that worry is a problematic strategy for all persons interested in resolving their problems.

This study has some notable limitations. Because high trait worry participants were not treatment-seeking, this limits our ability to generalize findings to clinically worried individuals. However, previous studies have identified impairment associated with worry in unselected samples (e.g., Hallion et al., 2014 ), as well as in samples of participants diagnosed with GAD (e.g., Pawluk et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, we hypothesized that the worry induction would impair problem solving even at low levels of trait worry, thus it was important to demonstrate that findings were not exclusive to a sample with clinically high levels of trait worry. Future studies should seek to replicate findings in clinical populations before such generalizations can be made. Moreover, because our study population consisted of college students, we cannot generalize findings to non-college student samples. As such these findings merit replication in other samples. On the other hand, our college student sample included adequate representation of racial diversity, with about 42% reflecting non-white groups.

Finally, because we asked participants to think about problems in their own lives, this may have led to some lack of uniformity in the complexity or severity level of problems participants were attempting to solve. For example, pathological worriers may be more likely than nonworriers to worry about even minor things. For this reason, we ensured that there was an equal balance of high and low trait worriers randomly assigned across conditions. Our procedure also directed participants to choose a problem for which they had some control over the outcome (i.e., we directed them to avoid problems for which there were no solutions). This may have also helped to prevent one group from selecting more intractable problems than another. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that problem severity varied systematically across conditions leading to the effects we found. Considering that studies of problem solving in real-life settings have been better able to detect worry-related impairment (e.g., Szabó & Lovibond, 2006 ) relative to those using hypothetical problems in an laboratory setting (e.g., Davey, 1994 ), we strove to create a task that was both externally valid and experimentally rigorous. However, future studies may wish to increase uniformity of this variable, while attempting to maintain external validity (such as by balancing participants by the types of problems they report or by ratings of problem severity).

In sum, this was the first study to experimentally manipulate worry immediately prior to problem solving in a controlled laboratory setting, and provides initial evidence that the worry process is detrimental to problem solving in this context. Although many individuals are prone to worry in the face of problems, believe that this is a helpful approach to confronting problems, and often conflate worry with active problem solving (e.g., Kelly & Kelly, 2007 ; Sugiura, 2013 ; Szabó & Lovibond, 2002 ), our findings suggest otherwise. We argue that worry is distinct from adaptive problem solving. Whereas it does direct attention to potential threats, worrying about a problem inhibits the ability to proactively address threats in an optimal way, and instead may repeatedly cycle people through their worst-case scenario fears. Data from this study argue that attempting to take a more objective stance when evaluating a problem, and refraining from catastrophic thinking, represent the most effective problem-solving strategies for both high and low trait worry individuals alike.

- Worrying about a personal problem lowered confidence in solutions for high trait worriers.

- Thinking objectively about a problem led to more effective solutions than worrying or focused breathing.

- State worry predicted less intention to implement solutions, while controlling for trait worry.

- Worrying beforehand led to elevated worry and anxiety after solving a personal problem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This study was partially supported by NIMH 1R01MH115128-01A1 to Michelle Newman.

Declarations of interest: none

Sandra Llera: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original draft preparation. Michelle G. Newman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review and editing.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5; 5th ed). Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Association. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson RJ, Goddard L, & Powell JH (2009). Social problem-solving processes and mood in college students: An examination of self-report and performance-based approaches . Cognitive Therapy and Research , 33 , 175–186. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9169-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beaudreau SA, MacKay-Brandt A, & Reynolds J. (2013). Application of a cognitive neuroscience perspective of cognitive control to late-life anxiety . Journal of Anxiety Disorders , 27 , 559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.006 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borkovec TD (1985). Worry: A potentially valuable concept . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 23 , 481–482. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90178-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borkovec TD, Robinson E, Pruzinsky T, & DePree JA (1983). Preliminary exploration of worry: Some characteristics and processes . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 21 , 9–16. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90121-3 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borkovec TD, & Roemer L. (1995). Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: Distraction from more emotionally distressing topics? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry , 26 , 25–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)00064-s [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clore GL, & Huntsinger JR (2007). How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought . Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 11 , 393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.005 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Zurilla TJ, & Goldfried MR (1971). Problem solving and behavior modification . Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 78 , 107–126. doi: 10.1037/h0031360 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davey GCL (1994). Worrying, social problem-solving abilities, and social problem-solving confidence . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 32 , 327–330. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90130-9 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davey GC, Hampton J, Farrell J, & Davidson S. (1992). Some characteristics of worrying: Evidence for worrying and anxiety as separate constructs . Personality and Individual Differences , 13 , 133–147. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90036-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dugas MJ, Gagnon F, Ladouceur R, & Freeston MH (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 36 , 215–226. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00070-3 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, & Calvo MG (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory . Emotion , 7 , 336–353. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fergus TA, Valentiner DP, Wu KD, & McGrath PB (2015). Examining the symptom-level specificity of negative problem orientation in a clinical sample . Cognitive Behaviour Therapy , 44 , 153–161. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.987314 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodwin H, Yiend J, & Hirsch CR (2017). Generalized Anxiety Disorder, worry and attention to threat: A systematic review . Clinical Psychology Review , 54 , 107–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.006 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gray JA (1990). Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition . Cognition & Emotion , 4 , 269–288. doi: 10.1080/02699939008410799 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hallion LS, Ruscio AM, & Jha AP (2014). Fractionating the role of executive control in control over worry: A preliminary investigation . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 54 , 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.12.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hallion LS, Steinman SA, & Kusmierski SN (2018). Difficulty concentrating in generalized anxiety disorder: An evaluation of incremental utility and relationship to worry . Journal of Anxiety Disorders , 53 , 39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.10.007 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes S, Hirsch C, & Mathews A. (2008). Restriction of working memory capacity during worry . Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 117 , 712–717. doi: 10.1037/a0012908 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hebert EA, Dugas MJ, Tulloch TG, & Holowka DW (2014). Positive beliefs about worry: A psychometric evaluation of the Why Worry-II . Personality and Individual Differences , 56 , 3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly WE, & Kelly KE (2007). A tale of two shoulds: The relationship between worry, beliefs one should find a right solution, and beliefs one should worry to solve problems . North American Journal of Psychology , 9 , 103–110. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ladouceur R, Blais F, Freeston MH, & Dugas MJ (1998). Problem solving and problem orientation in generalized anxiety disorder . Journal of Anxiety Disorders , 12 , 139–152. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(98)00002-4 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LaFreniere LS, & Newman MG (2019). Probabilistic learning by positive and negative reinforcement in generalized anxiety disorder . Clinical Psychological Science , 7 , 502–515. doi: 10.1177/2167702618809366 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyubomirsky S, & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (1995). Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 69 , 176. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.176 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyubomirsky S, Tucker KL, Caldwell ND, & Berg K. (1999). Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: Clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 77 , 1041. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1041 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mathews A. (1990). Why worry? The cognitive function of anxiety . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 28 , 455–468. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90132-3 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, & Borkovec TD, (1990) Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 28 , 487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Molina S, & Borkovec TD (1994). The Penn State Worry Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and associated characteristics In Davey GCL & Tallis F (Eds.), Worrying: Perspectives on theory, assessment and treatment (pp. 265–283). Oxford, England: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Newman MG, Jacobson NC, Zainal NH, Shin KE, Szkodny LE, & Sliwinski MJ (2019). The effects of worry in daily life: An ecological momentary assessment study supporting the tenets of the contrast avoidance model . Clinical Psychological Science , 7 , 794–810. doi: 10.1177/2167702619827019 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newman MG, & Llera SJ (2011). A novel theory of experiential avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: A review and synthesis of research supporting a Contrast Avoidance Model of worry . Clinical Psychology Review , 31 , 371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.008 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newman MG, Zuellig AR, Kachin KE, Constantino MJ, Przeworski A, Erickson T, & Cashman-McGrath L. (2002). Preliminary reliability and validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV: A revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder . Behavior Therapy , 33 , 215–233. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80026-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ottaviani C, Thayer JF, Verkuil B, Lonigro A, Medea B, Couyoumdjian A, & Brosschot JF (2016). Physiological concomitants of perseverative cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Psychological Bulletin , 142 , 231–259. doi: 10.1037/bul0000036 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pawluk EJ, & Koerner N. (2013). A preliminary investigation of impulsivity in generalized anxiety disorder . Personality and Individual Differences , 54 , 732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.027 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pawluk EJ, Koerner N, Tallon K, & Antony MM (2017). Unique correlates of problem solving effectiveness in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder . Cognitive Therapy and Research , 41 , 881–890. doi: 10.1007/s10608-017-9861-x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pieper S, Brosschot JF, van der Leeden R, & Thayer JF (2010). Prolonged cardiac effects of momentary assessed stressful events and worry episodes . Psychosomatic Medicine , 72 , 570–577. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dbc0e9 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rapee RM (1993). The utilisation of working memory by worry . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 31 , 617–620. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90114-A [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robichaud M, & Dugas MJ (2005). Negative problem orientation (Part II): construct validity and specificity to worry . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 43 , 403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwarz N, & Skurnik IU (2003). Feeling and thinking: Implications for problem solving In Davidson JE & Sternberg RJ (Eds.), The psychology of problem solving (pp. 263–290). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511615771.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Startup HM, & Davey GCL (2003). Inflated responsibility and the use of stop rules for catastrophic worrying . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 41 , 495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00245-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Startup HM, & Erickson TM (2006). The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) In Davey GCL & Wells A (Eds.), Worry and its psychological disorders: Theory, assessment and treatment . (pp. 101–119). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9780470713143.ch7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stefanopoulou E, Hirsch CR, Hayes S, Adlam A, & Coker S. (2014). Are attentional control resources reduced by worry in generalized anxiety disorder? Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 123 , 330–335. doi: 10.1037/a0036343 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sugiura Y. (2007). Responsibility to continue thinking and worrying: Evidence of incremental validity . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 45 , 1619–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sugiura Y. (2013). The dual effects of critical thinking disposition on worry . PLoS ONE , 8 , e79714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079714 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Szabó M, & Lovibond PF (2002). The cognitive content of naturally occurring worry episodes . Cognitive Therapy and Research , 26 , 167–177. doi: 10.1023/A:1014565602111 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Szabó M, & Lovibond PF (2006). Worry episodes and perceived problem solving: A diary-based approach . Anxiety, Stress & Coping , 19 , 175–187. doi: 10.1080/10615800600643562 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tallis F, Eysenck M, & Mathews A. (1991). Elevated evidence requirements and worry . Personality and Individual Differences , 12 , 21–27. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(91)90128-X [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Trezise K, & Reeve RA (2016). Worry and working memory influence each other iteratively over time . Cognition and Emotion , 30 , 353–368. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.1002755 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zetsche U, Bürkner P-C, & Schulze L. (2018). Shedding light on the association between repetitive negative thinking and deficits in cognitive control – A meta-analysis . Clinical Psychology Review , 63 , 56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Australia (AUD $)

- Austria (EUR €)

- Belgium (EUR €)

- Canada (CAD $)

- Czechia (CZK Kč)

- Denmark (DKK kr.)

- Finland (EUR €)

- France (EUR €)

- Germany (EUR €)

- Hong Kong SAR (HKD $)

- Ireland (EUR €)

- Israel (ILS ₪)

- Italy (EUR €)

- Japan (JPY ¥)

- Malaysia (MYR RM)

- Netherlands (EUR €)

- New Zealand (NZD $)

- Norway (USD $)

- Poland (PLN zł)

- Portugal (EUR €)

- Singapore (SGD $)

- South Korea (KRW ₩)

- Spain (EUR €)

- Sweden (SEK kr)

- Switzerland (CHF CHF)

- United Arab Emirates (AED د.إ)

- United Kingdom (GBP £)

- United States (USD $)

Sign up and save

Sign up for our mailing list to receive discounts and exclusive offers.

Solve Problems Before They Happen: Proactive Strategies for Success

We all know that prevention is better than cure, and this is especially true when it comes to problem-solving. Proactive problem-solving is a crucial skill in both personal and professional life that can lead to long-term success. In this article, we will discuss the importance of proactive problem-solving and provide you with strategies to adopt a proactive approach to prevent problems before they even occur.

Understanding the Importance of Proactive Problem-Solving

The most successful individuals and organizations are those who take a proactive approach to problem-solving. Proactive problem-solving involves identifying potential problems before they occur and taking action to prevent them from becoming an issue. This approach minimizes the risk of facing unexpected challenges that can cause an array of consequences, including financial loss, missed opportunities, reputational damage, and emotional stress. With proactive problem-solving, you can avoid these downsides and ensure smooth operations, happier stakeholders, and greater chances for success.

One of the key benefits of proactive problem-solving is that it allows you to stay ahead of the competition. By identifying potential issues before they arise, you can take steps to address them and maintain a competitive edge. This can be especially important in industries that are constantly evolving, where being able to adapt quickly can make all the difference.

Another advantage of proactive problem-solving is that it can help you build stronger relationships with your stakeholders. By demonstrating that you are proactive and committed to addressing potential issues, you can build trust and confidence with your customers, employees, and partners. This can lead to increased loyalty, better collaboration, and a more positive reputation overall.

Identifying Potential Problems in Advance

To adopt a proactive problem-solving approach, you must first identify the potential problems that could occur. Conduct a systematic review of your personal or professional life and consider the future. You can also study your past experiences to recognize trends and recurring issues. This foresight will provide you with the knowledge to recognize potential problems and take action to prevent or mitigate them.

One effective way to identify potential problems is to seek feedback from others. Ask for input from colleagues, friends, or family members who have experience in the area you are concerned about. They may be able to provide valuable insights and perspectives that you had not considered before.

Another approach is to conduct research and gather information about similar situations or industries. This can help you anticipate potential challenges and prepare accordingly. By staying informed and up-to-date, you can stay ahead of potential problems and be better equipped to handle them if they do arise.

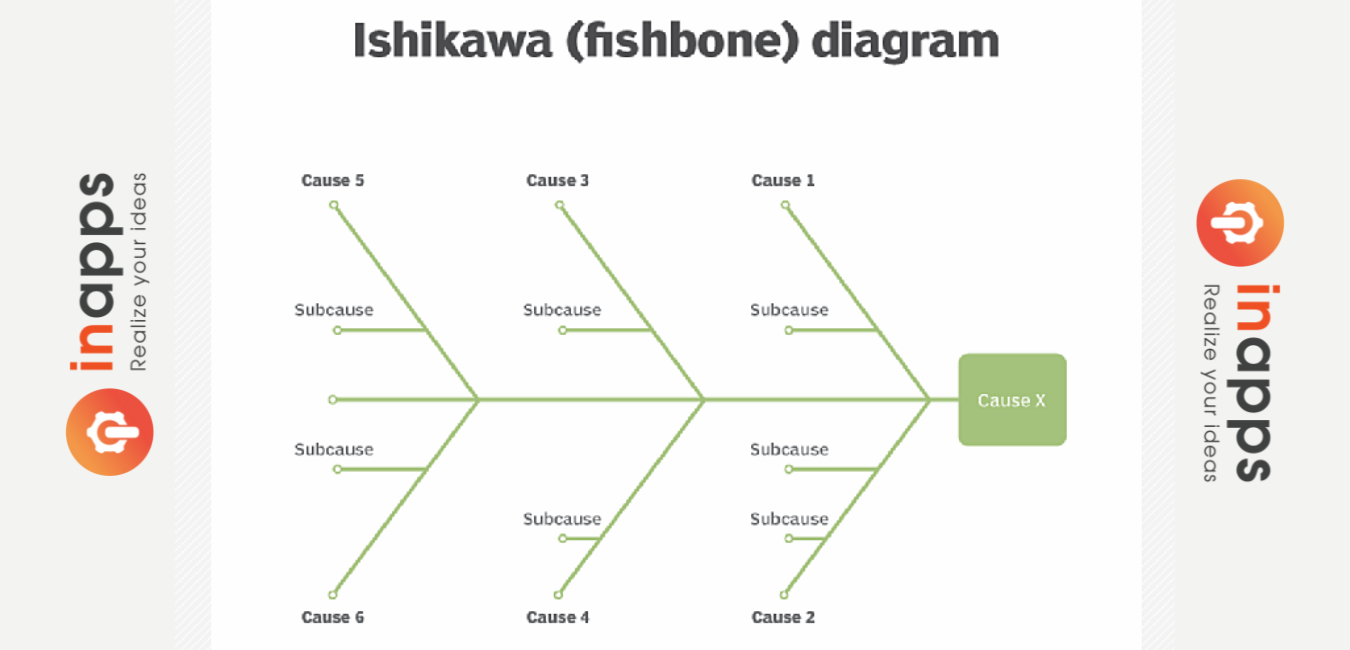

Analyzing the Root Causes of Problems

When you have identified potential problems, you must analyze their root causes to understand the underlying reason for their occurrence. This involves conducting a rigorous analysis of the problem, including researching and tracking data, conducting team discussions, and brainstorming sessions. This analysis will enable you to develop a comprehensive understanding of the problem, enabling you to develop effective solutions.

It is important to note that analyzing the root causes of problems is not a one-time event. As you implement solutions, it is important to monitor their effectiveness and track any new issues that may arise. This ongoing analysis will help you to identify any underlying issues that may be contributing to the problem, allowing you to make necessary adjustments and improvements to your solutions.

Implementing Preventative Measures to Avoid Future Problems

Once you have identified potential problems and analyzed their root causes, the next step is to implement preventative measures to avoid future issues. This can include adopting new policies and procedures, improving training and education programs, providing resources and tools to team members, and implementing new technologies. By implementing preventative measures, you can create a safer and more efficient environment for your personal or professional life.

One important aspect of implementing preventative measures is to regularly review and update them. As new technologies and best practices emerge, it is important to ensure that your preventative measures are still effective and relevant. This can involve conducting regular risk assessments and seeking feedback from team members and stakeholders.

Another key factor in implementing preventative measures is to foster a culture of safety and accountability. This involves encouraging team members to report potential issues and providing them with the support and resources they need to do so. It also involves holding individuals and teams accountable for following policies and procedures, and addressing any issues that arise in a timely and effective manner.

Creating a Culture of Proactivity in Your Organization

If you are a leader in an organization, it is essential to create a culture of proactivity in your team. Encourage your team members to adopt a proactive approach to problem-solving by rewarding innovation and taking calculated risks. Emphasize the importance of early detection, root cause analysis, and pragmatic preventative measures. Create a continuous learning culture that encourages individuals to seek feedback and improve their performance continually.

One way to foster a culture of proactivity is to provide your team members with the necessary resources and tools to succeed. This includes access to training programs, mentorship opportunities, and the latest technology. By investing in your team's development, you are demonstrating your commitment to their success and encouraging them to take ownership of their work.

Another critical aspect of creating a proactive culture is to lead by example. As a leader, you must model the behavior you want to see in your team. This means taking initiative, being accountable for your actions, and demonstrating a willingness to learn and grow. By setting the tone for proactivity, you can inspire your team to follow suit and create a culture of continuous improvement.

Teaching Others to Think Proactively

You can also help others by teaching them to think proactively. Share your personal experiences with proactive problem-solving and how it has benefited you in your life. Encourage them to identify potential problems and analyze their root causes. Provide them with the tools and resources they need to implement preventative measures that can prevent problems from occurring in the first place.

Additionally, it is important to emphasize the importance of taking action and not just identifying potential problems. Encourage others to develop a plan of action and follow through with it. Help them to prioritize tasks and allocate resources effectively. By teaching others to think proactively and take action, you can empower them to become more effective problem-solvers and achieve their goals more efficiently.

Building Resilience to Handle Unexpected Challenges

Even with proactive problem-solving strategies in place, you may still face unexpected challenges. Therefore, it is essential to build resilience to handle these situations effectively. Resilience is about developing mental and emotional strength to overcome unexpected challenges and bounce back from setbacks. This involves developing positive coping mechanisms, maintaining a healthy work-life balance, and having a support network in place.

One way to build resilience is to practice mindfulness and meditation. These practices can help you stay present in the moment and manage stress and anxiety. Additionally, regular exercise and a healthy diet can also contribute to building resilience by improving physical and mental health.

It is also important to remember that building resilience is an ongoing process. It requires consistent effort and a willingness to learn and grow from challenges. By developing resilience, you can not only handle unexpected challenges but also thrive in the face of adversity.

Communicating Effectively to Prevent Misunderstandings

Misunderstandings and communication problems can also cause significant issues in personal and professional life. Therefore, it is essential to communicate effectively to prevent these issues. This involves actively listening, clarifying instructions and expectations, expressing yourself clearly and respectfully, and providing feedback effectively. Effective communication can help prevent misunderstandings from escalating into more serious problems.