The Advantages and Limitations of Single Case Study Analysis

As Andrew Bennett and Colin Elman have recently noted, qualitative research methods presently enjoy “an almost unprecedented popularity and vitality… in the international relations sub-field”, such that they are now “indisputably prominent, if not pre-eminent” (2010: 499). This is, they suggest, due in no small part to the considerable advantages that case study methods in particular have to offer in studying the “complex and relatively unstructured and infrequent phenomena that lie at the heart of the subfield” (Bennett and Elman, 2007: 171). Using selected examples from within the International Relations literature[1], this paper aims to provide a brief overview of the main principles and distinctive advantages and limitations of single case study analysis. Divided into three inter-related sections, the paper therefore begins by first identifying the underlying principles that serve to constitute the case study as a particular research strategy, noting the somewhat contested nature of the approach in ontological, epistemological, and methodological terms. The second part then looks to the principal single case study types and their associated advantages, including those from within the recent ‘third generation’ of qualitative International Relations (IR) research. The final section of the paper then discusses the most commonly articulated limitations of single case studies; while accepting their susceptibility to criticism, it is however suggested that such weaknesses are somewhat exaggerated. The paper concludes that single case study analysis has a great deal to offer as a means of both understanding and explaining contemporary international relations.

The term ‘case study’, John Gerring has suggested, is “a definitional morass… Evidently, researchers have many different things in mind when they talk about case study research” (2006a: 17). It is possible, however, to distil some of the more commonly-agreed principles. One of the most prominent advocates of case study research, Robert Yin (2009: 14) defines it as “an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”. What this definition usefully captures is that case studies are intended – unlike more superficial and generalising methods – to provide a level of detail and understanding, similar to the ethnographer Clifford Geertz’s (1973) notion of ‘thick description’, that allows for the thorough analysis of the complex and particularistic nature of distinct phenomena. Another frequently cited proponent of the approach, Robert Stake, notes that as a form of research the case study “is defined by interest in an individual case, not by the methods of inquiry used”, and that “the object of study is a specific, unique, bounded system” (2008: 443, 445). As such, three key points can be derived from this – respectively concerning issues of ontology, epistemology, and methodology – that are central to the principles of single case study research.

First, the vital notion of ‘boundedness’ when it comes to the particular unit of analysis means that defining principles should incorporate both the synchronic (spatial) and diachronic (temporal) elements of any so-called ‘case’. As Gerring puts it, a case study should be “an intensive study of a single unit… a spatially bounded phenomenon – e.g. a nation-state, revolution, political party, election, or person – observed at a single point in time or over some delimited period of time” (2004: 342). It is important to note, however, that – whereas Gerring refers to a single unit of analysis – it may be that attention also necessarily be given to particular sub-units. This points to the important difference between what Yin refers to as an ‘holistic’ case design, with a single unit of analysis, and an ’embedded’ case design with multiple units of analysis (Yin, 2009: 50-52). The former, for example, would examine only the overall nature of an international organization, whereas the latter would also look to specific departments, programmes, or policies etc.

Secondly, as Tim May notes of the case study approach, “even the most fervent advocates acknowledge that the term has entered into understandings with little specification or discussion of purpose and process” (2011: 220). One of the principal reasons for this, he argues, is the relationship between the use of case studies in social research and the differing epistemological traditions – positivist, interpretivist, and others – within which it has been utilised. Philosophy of science concerns are obviously a complex issue, and beyond the scope of much of this paper. That said, the issue of how it is that we know what we know – of whether or not a single independent reality exists of which we as researchers can seek to provide explanation – does lead us to an important distinction to be made between so-called idiographic and nomothetic case studies (Gerring, 2006b). The former refers to those which purport to explain only a single case, are concerned with particularisation, and hence are typically (although not exclusively) associated with more interpretivist approaches. The latter are those focused studies that reflect upon a larger population and are more concerned with generalisation, as is often so with more positivist approaches[2]. The importance of this distinction, and its relation to the advantages and limitations of single case study analysis, is returned to below.

Thirdly, in methodological terms, given that the case study has often been seen as more of an interpretivist and idiographic tool, it has also been associated with a distinctly qualitative approach (Bryman, 2009: 67-68). However, as Yin notes, case studies can – like all forms of social science research – be exploratory, descriptive, and/or explanatory in nature. It is “a common misconception”, he notes, “that the various research methods should be arrayed hierarchically… many social scientists still deeply believe that case studies are only appropriate for the exploratory phase of an investigation” (Yin, 2009: 6). If case studies can reliably perform any or all three of these roles – and given that their in-depth approach may also require multiple sources of data and the within-case triangulation of methods – then it becomes readily apparent that they should not be limited to only one research paradigm. Exploratory and descriptive studies usually tend toward the qualitative and inductive, whereas explanatory studies are more often quantitative and deductive (David and Sutton, 2011: 165-166). As such, the association of case study analysis with a qualitative approach is a “methodological affinity, not a definitional requirement” (Gerring, 2006a: 36). It is perhaps better to think of case studies as transparadigmatic; it is mistaken to assume single case study analysis to adhere exclusively to a qualitative methodology (or an interpretivist epistemology) even if it – or rather, practitioners of it – may be so inclined. By extension, this also implies that single case study analysis therefore remains an option for a multitude of IR theories and issue areas; it is how this can be put to researchers’ advantage that is the subject of the next section.

Having elucidated the defining principles of the single case study approach, the paper now turns to an overview of its main benefits. As noted above, a lack of consensus still exists within the wider social science literature on the principles and purposes – and by extension the advantages and limitations – of case study research. Given that this paper is directed towards the particular sub-field of International Relations, it suggests Bennett and Elman’s (2010) more discipline-specific understanding of contemporary case study methods as an analytical framework. It begins however, by discussing Harry Eckstein’s seminal (1975) contribution to the potential advantages of the case study approach within the wider social sciences.

Eckstein proposed a taxonomy which usefully identified what he considered to be the five most relevant types of case study. Firstly were so-called configurative-idiographic studies, distinctly interpretivist in orientation and predicated on the assumption that “one cannot attain prediction and control in the natural science sense, but only understanding ( verstehen )… subjective values and modes of cognition are crucial” (1975: 132). Eckstein’s own sceptical view was that any interpreter ‘simply’ considers a body of observations that are not self-explanatory and “without hard rules of interpretation, may discern in them any number of patterns that are more or less equally plausible” (1975: 134). Those of a more post-modernist bent, of course – sharing an “incredulity towards meta-narratives”, in Lyotard’s (1994: xxiv) evocative phrase – would instead suggest that this more free-form approach actually be advantageous in delving into the subtleties and particularities of individual cases.

Eckstein’s four other types of case study, meanwhile, promote a more nomothetic (and positivist) usage. As described, disciplined-configurative studies were essentially about the use of pre-existing general theories, with a case acting “passively, in the main, as a receptacle for putting theories to work” (Eckstein, 1975: 136). As opposed to the opportunity this presented primarily for theory application, Eckstein identified heuristic case studies as explicit theoretical stimulants – thus having instead the intended advantage of theory-building. So-called p lausibility probes entailed preliminary attempts to determine whether initial hypotheses should be considered sound enough to warrant more rigorous and extensive testing. Finally, and perhaps most notably, Eckstein then outlined the idea of crucial case studies , within which he also included the idea of ‘most-likely’ and ‘least-likely’ cases; the essential characteristic of crucial cases being their specific theory-testing function.

Whilst Eckstein’s was an early contribution to refining the case study approach, Yin’s (2009: 47-52) more recent delineation of possible single case designs similarly assigns them roles in the applying, testing, or building of theory, as well as in the study of unique cases[3]. As a subset of the latter, however, Jack Levy (2008) notes that the advantages of idiographic cases are actually twofold. Firstly, as inductive/descriptive cases – akin to Eckstein’s configurative-idiographic cases – whereby they are highly descriptive, lacking in an explicit theoretical framework and therefore taking the form of “total history”. Secondly, they can operate as theory-guided case studies, but ones that seek only to explain or interpret a single historical episode rather than generalise beyond the case. Not only does this therefore incorporate ‘single-outcome’ studies concerned with establishing causal inference (Gerring, 2006b), it also provides room for the more postmodern approaches within IR theory, such as discourse analysis, that may have developed a distinct methodology but do not seek traditional social scientific forms of explanation.

Applying specifically to the state of the field in contemporary IR, Bennett and Elman identify a ‘third generation’ of mainstream qualitative scholars – rooted in a pragmatic scientific realist epistemology and advocating a pluralistic approach to methodology – that have, over the last fifteen years, “revised or added to essentially every aspect of traditional case study research methods” (2010: 502). They identify ‘process tracing’ as having emerged from this as a central method of within-case analysis. As Bennett and Checkel observe, this carries the advantage of offering a methodologically rigorous “analysis of evidence on processes, sequences, and conjunctures of events within a case, for the purposes of either developing or testing hypotheses about causal mechanisms that might causally explain the case” (2012: 10).

Harnessing various methods, process tracing may entail the inductive use of evidence from within a case to develop explanatory hypotheses, and deductive examination of the observable implications of hypothesised causal mechanisms to test their explanatory capability[4]. It involves providing not only a coherent explanation of the key sequential steps in a hypothesised process, but also sensitivity to alternative explanations as well as potential biases in the available evidence (Bennett and Elman 2010: 503-504). John Owen (1994), for example, demonstrates the advantages of process tracing in analysing whether the causal factors underpinning democratic peace theory are – as liberalism suggests – not epiphenomenal, but variously normative, institutional, or some given combination of the two or other unexplained mechanism inherent to liberal states. Within-case process tracing has also been identified as advantageous in addressing the complexity of path-dependent explanations and critical junctures – as for example with the development of political regime types – and their constituent elements of causal possibility, contingency, closure, and constraint (Bennett and Elman, 2006b).

Bennett and Elman (2010: 505-506) also identify the advantages of single case studies that are implicitly comparative: deviant, most-likely, least-likely, and crucial cases. Of these, so-called deviant cases are those whose outcome does not fit with prior theoretical expectations or wider empirical patterns – again, the use of inductive process tracing has the advantage of potentially generating new hypotheses from these, either particular to that individual case or potentially generalisable to a broader population. A classic example here is that of post-independence India as an outlier to the standard modernisation theory of democratisation, which holds that higher levels of socio-economic development are typically required for the transition to, and consolidation of, democratic rule (Lipset, 1959; Diamond, 1992). Absent these factors, MacMillan’s single case study analysis (2008) suggests the particularistic importance of the British colonial heritage, the ideology and leadership of the Indian National Congress, and the size and heterogeneity of the federal state.

Most-likely cases, as per Eckstein above, are those in which a theory is to be considered likely to provide a good explanation if it is to have any application at all, whereas least-likely cases are ‘tough test’ ones in which the posited theory is unlikely to provide good explanation (Bennett and Elman, 2010: 505). Levy (2008) neatly refers to the inferential logic of the least-likely case as the ‘Sinatra inference’ – if a theory can make it here, it can make it anywhere. Conversely, if a theory cannot pass a most-likely case, it is seriously impugned. Single case analysis can therefore be valuable for the testing of theoretical propositions, provided that predictions are relatively precise and measurement error is low (Levy, 2008: 12-13). As Gerring rightly observes of this potential for falsification:

“a positivist orientation toward the work of social science militates toward a greater appreciation of the case study format, not a denigration of that format, as is usually supposed” (Gerring, 2007: 247, emphasis added).

In summary, the various forms of single case study analysis can – through the application of multiple qualitative and/or quantitative research methods – provide a nuanced, empirically-rich, holistic account of specific phenomena. This may be particularly appropriate for those phenomena that are simply less amenable to more superficial measures and tests (or indeed any substantive form of quantification) as well as those for which our reasons for understanding and/or explaining them are irreducibly subjective – as, for example, with many of the normative and ethical issues associated with the practice of international relations. From various epistemological and analytical standpoints, single case study analysis can incorporate both idiographic sui generis cases and, where the potential for generalisation may exist, nomothetic case studies suitable for the testing and building of causal hypotheses. Finally, it should not be ignored that a signal advantage of the case study – with particular relevance to international relations – also exists at a more practical rather than theoretical level. This is, as Eckstein noted, “that it is economical for all resources: money, manpower, time, effort… especially important, of course, if studies are inherently costly, as they are if units are complex collective individuals ” (1975: 149-150, emphasis added).

Limitations

Single case study analysis has, however, been subject to a number of criticisms, the most common of which concern the inter-related issues of methodological rigour, researcher subjectivity, and external validity. With regard to the first point, the prototypical view here is that of Zeev Maoz (2002: 164-165), who suggests that “the use of the case study absolves the author from any kind of methodological considerations. Case studies have become in many cases a synonym for freeform research where anything goes”. The absence of systematic procedures for case study research is something that Yin (2009: 14-15) sees as traditionally the greatest concern due to a relative absence of methodological guidelines. As the previous section suggests, this critique seems somewhat unfair; many contemporary case study practitioners – and representing various strands of IR theory – have increasingly sought to clarify and develop their methodological techniques and epistemological grounding (Bennett and Elman, 2010: 499-500).

A second issue, again also incorporating issues of construct validity, concerns that of the reliability and replicability of various forms of single case study analysis. This is usually tied to a broader critique of qualitative research methods as a whole. However, whereas the latter obviously tend toward an explicitly-acknowledged interpretive basis for meanings, reasons, and understandings:

“quantitative measures appear objective, but only so long as we don’t ask questions about where and how the data were produced… pure objectivity is not a meaningful concept if the goal is to measure intangibles [as] these concepts only exist because we can interpret them” (Berg and Lune, 2010: 340).

The question of researcher subjectivity is a valid one, and it may be intended only as a methodological critique of what are obviously less formalised and researcher-independent methods (Verschuren, 2003). Owen (1994) and Layne’s (1994) contradictory process tracing results of interdemocratic war-avoidance during the Anglo-American crisis of 1861 to 1863 – from liberal and realist standpoints respectively – are a useful example. However, it does also rest on certain assumptions that can raise deeper and potentially irreconcilable ontological and epistemological issues. There are, regardless, plenty such as Bent Flyvbjerg (2006: 237) who suggest that the case study contains no greater bias toward verification than other methods of inquiry, and that “on the contrary, experience indicates that the case study contains a greater bias toward falsification of preconceived notions than toward verification”.

The third and arguably most prominent critique of single case study analysis is the issue of external validity or generalisability. How is it that one case can reliably offer anything beyond the particular? “We always do better (or, in the extreme, no worse) with more observation as the basis of our generalization”, as King et al write; “in all social science research and all prediction, it is important that we be as explicit as possible about the degree of uncertainty that accompanies out prediction” (1994: 212). This is an unavoidably valid criticism. It may be that theories which pass a single crucial case study test, for example, require rare antecedent conditions and therefore actually have little explanatory range. These conditions may emerge more clearly, as Van Evera (1997: 51-54) notes, from large-N studies in which cases that lack them present themselves as outliers exhibiting a theory’s cause but without its predicted outcome. As with the case of Indian democratisation above, it would logically be preferable to conduct large-N analysis beforehand to identify that state’s non-representative nature in relation to the broader population.

There are, however, three important qualifiers to the argument about generalisation that deserve particular mention here. The first is that with regard to an idiographic single-outcome case study, as Eckstein notes, the criticism is “mitigated by the fact that its capability to do so [is] never claimed by its exponents; in fact it is often explicitly repudiated” (1975: 134). Criticism of generalisability is of little relevance when the intention is one of particularisation. A second qualifier relates to the difference between statistical and analytical generalisation; single case studies are clearly less appropriate for the former but arguably retain significant utility for the latter – the difference also between explanatory and exploratory, or theory-testing and theory-building, as discussed above. As Gerring puts it, “theory confirmation/disconfirmation is not the case study’s strong suit” (2004: 350). A third qualification relates to the issue of case selection. As Seawright and Gerring (2008) note, the generalisability of case studies can be increased by the strategic selection of cases. Representative or random samples may not be the most appropriate, given that they may not provide the richest insight (or indeed, that a random and unknown deviant case may appear). Instead, and properly used , atypical or extreme cases “often reveal more information because they activate more actors… and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied” (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Of course, this also points to the very serious limitation, as hinted at with the case of India above, that poor case selection may alternatively lead to overgeneralisation and/or grievous misunderstandings of the relationship between variables or processes (Bennett and Elman, 2006a: 460-463).

As Tim May (2011: 226) notes, “the goal for many proponents of case studies […] is to overcome dichotomies between generalizing and particularizing, quantitative and qualitative, deductive and inductive techniques”. Research aims should drive methodological choices, rather than narrow and dogmatic preconceived approaches. As demonstrated above, there are various advantages to both idiographic and nomothetic single case study analyses – notably the empirically-rich, context-specific, holistic accounts that they have to offer, and their contribution to theory-building and, to a lesser extent, that of theory-testing. Furthermore, while they do possess clear limitations, any research method involves necessary trade-offs; the inherent weaknesses of any one method, however, can potentially be offset by situating them within a broader, pluralistic mixed-method research strategy. Whether or not single case studies are used in this fashion, they clearly have a great deal to offer.

References

Bennett, A. and Checkel, J. T. (2012) ‘Process Tracing: From Philosophical Roots to Best Practice’, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 21/2012, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University: Vancouver.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2006a) ‘Qualitative Research: Recent Developments in Case Study Methods’, Annual Review of Political Science , 9, 455-476.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2006b) ‘Complex Causal Relations and Case Study Methods: The Example of Path Dependence’, Political Analysis , 14, 3, 250-267.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2007) ‘Case Study Methods in the International Relations Subfield’, Comparative Political Studies , 40, 2, 170-195.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2010) Case Study Methods. In C. Reus-Smit and D. Snidal (eds) The Oxford Handbook of International Relations . Oxford University Press: Oxford. Ch. 29.

Berg, B. and Lune, H. (2012) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . Pearson: London.

Bryman, A. (2012) Social Research Methods . Oxford University Press: Oxford.

David, M. and Sutton, C. D. (2011) Social Research: An Introduction . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

Diamond, J. (1992) ‘Economic development and democracy reconsidered’, American Behavioral Scientist , 35, 4/5, 450-499.

Eckstein, H. (1975) Case Study and Theory in Political Science. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, and P. Foster (eds) Case Study Method . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006) ‘Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research’, Qualitative Inquiry , 12, 2, 219-245.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays by Clifford Geertz . Basic Books Inc: New York.

Gerring, J. (2004) ‘What is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?’, American Political Science Review , 98, 2, 341-354.

Gerring, J. (2006a) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Gerring, J. (2006b) ‘Single-Outcome Studies: A Methodological Primer’, International Sociology , 21, 5, 707-734.

Gerring, J. (2007) ‘Is There a (Viable) Crucial-Case Method?’, Comparative Political Studies , 40, 3, 231-253.

King, G., Keohane, R. O. and Verba, S. (1994) Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research . Princeton University Press: Chichester.

Layne, C. (1994) ‘Kant or Cant: The Myth of the Democratic Peace’, International Security , 19, 2, 5-49.

Levy, J. S. (2008) ‘Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference’, Conflict Management and Peace Science , 25, 1-18.

Lipset, S. M. (1959) ‘Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy’, The American Political Science Review , 53, 1, 69-105.

Lyotard, J-F. (1984) The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge . University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

MacMillan, A. (2008) ‘Deviant Democratization in India’, Democratization , 15, 4, 733-749.

Maoz, Z. (2002) Case study methodology in international studies: from storytelling to hypothesis testing. In F. P. Harvey and M. Brecher (eds) Evaluating Methodology in International Studies . University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor.

May, T. (2011) Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process . Open University Press: Maidenhead.

Owen, J. M. (1994) ‘How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace’, International Security , 19, 2, 87-125.

Seawright, J. and Gerring, J. (2008) ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options’, Political Research Quarterly , 61, 2, 294-308.

Stake, R. E. (2008) Qualitative Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (eds) Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry . Sage Publications: Los Angeles. Ch. 17.

Van Evera, S. (1997) Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science . Cornell University Press: Ithaca.

Verschuren, P. J. M. (2003) ‘Case study as a research strategy: some ambiguities and opportunities’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 6, 2, 121-139.

Yin, R. K. (2009) Case Study Research: Design and Methods . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

[1] The paper follows convention by differentiating between ‘International Relations’ as the academic discipline and ‘international relations’ as the subject of study.

[2] There is some similarity here with Stake’s (2008: 445-447) notion of intrinsic cases, those undertaken for a better understanding of the particular case, and instrumental ones that provide insight for the purposes of a wider external interest.

[3] These may be unique in the idiographic sense, or in nomothetic terms as an exception to the generalising suppositions of either probabilistic or deterministic theories (as per deviant cases, below).

[4] Although there are “philosophical hurdles to mount”, according to Bennett and Checkel, there exists no a priori reason as to why process tracing (as typically grounded in scientific realism) is fundamentally incompatible with various strands of positivism or interpretivism (2012: 18-19). By extension, it can therefore be incorporated by a range of contemporary mainstream IR theories.

— Written by: Ben Willis Written at: University of Plymouth Written for: David Brockington Date written: January 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Identity in International Conflicts: A Case Study of the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Imperialism’s Legacy in the Study of Contemporary Politics: The Case of Hegemonic Stability Theory

- Recreating a Nation’s Identity Through Symbolism: A Chinese Case Study

- Ontological Insecurity: A Case Study on Israeli-Palestinian Conflict in Jerusalem

- Terrorists or Freedom Fighters: A Case Study of ETA

- A Critical Assessment of Eco-Marxism: A Ghanaian Case Study

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 22 November 2022

Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories

- Lyndsey Nickels ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0311-3524 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Fischer-Baum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6067-0538 3 &

- Wendy Best ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8375-5916 4

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 1 , pages 733–747 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

627 Accesses

5 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neurological disorders

Psychology embraces a diverse range of methodologies. However, most rely on averaging group data to draw conclusions. In this Perspective, we argue that single case methodology is a valuable tool for developing and extending psychological theories. We stress the importance of single case and case series research, drawing on classic and contemporary cases in which cognitive and perceptual deficits provide insights into typical cognitive processes in domains such as memory, delusions, reading and face perception. We unpack the key features of single case methodology, describe its strengths, its value in adjudicating between theories, and outline its benefits for a better understanding of deficits and hence more appropriate interventions. The unique insights that single case studies have provided illustrate the value of in-depth investigation within an individual. Single case methodology has an important place in the psychologist’s toolkit and it should be valued as a primary research tool.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Federico Cavanna, Stephanie Muller, … Enzo Tagliazucchi

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Joseph M. Rootman, Pamela Kryskow, … Zach Walsh

Interviews in the social sciences

Eleanor Knott, Aliya Hamid Rao, … Chana Teeger

Corkin, S. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life Of The Amnesic Patient, H. M . Vol. XIX, 364 (Basic Books, 2013).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Psychology: From Inquiry To Understanding (Pearson, 2019).

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., Nock, M. K. & Wegner, D. M. Psychology (Worth Publishers, 2019).

Eysenck, M. W. & Brysbaert, M. Fundamentals Of Cognition (Routledge, 2018).

Squire, L. R. Memory and brain systems: 1969–2009. J. Neurosci. 29 , 12711–12716 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Corkin, S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 , 153–160 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schubert, T. M. et al. Lack of awareness despite complex visual processing: evidence from event-related potentials in a case of selective metamorphopsia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 16055–16064 (2020).

Behrmann, M. & Plaut, D. C. Bilateral hemispheric processing of words and faces: evidence from word impairments in prosopagnosia and face impairments in pure alexia. Cereb. Cortex 24 , 1102–1118 (2014).

Plaut, D. C. & Behrmann, M. Complementary neural representations for faces and words: a computational exploration. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 251–275 (2011).

Haxby, J. V. et al. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293 , 2425–2430 (2001).

Hirshorn, E. A. et al. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 8162–8167 (2016).

Kosakowski, H. L. et al. Selective responses to faces, scenes, and bodies in the ventral visual pathway of infants. Curr. Biol. 32 , 265–274.e5 (2022).

Harlow, J. Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Med. Surgical J . https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.11.2.281 (1848).

Broca, P. Remarks on the seat of the faculty of articulated language, following an observation of aphemia (loss of speech). Bull. Soc. Anat. 6 , 330–357 (1861).

Google Scholar

Dejerine, J. Contribution A L’étude Anatomo-pathologique Et Clinique Des Différentes Variétés De Cécité Verbale: I. Cécité Verbale Avec Agraphie Ou Troubles Très Marqués De L’écriture; II. Cécité Verbale Pure Avec Intégrité De L’écriture Spontanée Et Sous Dictée (Société de Biologie, 1892).

Liepmann, H. Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (“motorischen Asymbolie”) auf Grund eines Falles von einseitiger Apraxie (Fortsetzung). Eur. Neurol. 8 , 102–116 (1900).

Article Google Scholar

Basso, A., Spinnler, H., Vallar, G. & Zanobio, M. E. Left hemisphere damage and selective impairment of auditory verbal short-term memory. A case study. Neuropsychologia 20 , 263–274 (1982).

Humphreys, G. W. & Riddoch, M. J. The fractionation of visual agnosia. In Visual Object Processing: A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach 281–306 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987).

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. & Howard, D. A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach To Assessment And Intervention In Aphasia (Psychology Press, 2014).

Caramazza, A. On drawing inferences about the structure of normal cognitive systems from the analysis of patterns of impaired performance: the case for single-patient studies. Brain Cogn. 5 , 41–66 (1986).

Caramazza, A. & McCloskey, M. The case for single-patient studies. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 5 , 517–527 (1988).

Shallice, T. Cognitive neuropsychology and its vicissitudes: the fate of Caramazza’s axioms. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 385–411 (2015).

Shallice, T. From Neuropsychology To Mental Structure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988).

Coltheart, M. Assumptions and methods in cognitive neuropscyhology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 3–22 (Psychology Press, 2001).

McCloskey, M. & Chaisilprungraung, T. The value of cognitive neuropsychology: the case of vision research. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 412–419 (2017).

McCloskey, M. The future of cognitive neuropsychology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 593–610 (Psychology Press, 2001).

Lashley, K. S. In search of the engram. In Physiological Mechanisms in Animal Behavior 454–482 (Academic Press, 1950).

Squire, L. R. & Wixted, J. T. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34 , 259–288 (2011).

Stone, G. O., Vanhoy, M. & Orden, G. C. V. Perception is a two-way street: feedforward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 36 , 337–359 (1997).

Perfetti, C. A. The psycholinguistics of spelling and reading. In Learning To Spell: Research, Theory, And Practice Across Languages 21–38 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997).

Nickels, L. The autocue? self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 9 , 155–182 (1992).

Rapp, B., Benzing, L. & Caramazza, A. The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 14 , 71–104 (1997).

Bonin, P., Roux, S. & Barry, C. Translating nonverbal pictures into verbal word names. Understanding lexical access and retrieval. In Past, Present, And Future Contributions Of Cognitive Writing Research To Cognitive Psychology 315–522 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Gombert, J.-E. Role of phonological and orthographic codes in picture naming and writing: an interference paradigm study. Cah. Psychol. Cogn./Current Psychol. Cogn. 16 , 299–324 (1997).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Peereman, R. Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychol. 99 , 311–328 (1998).

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E. & McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 , 551–565 (1996).

Jeffreys, D. A. Evoked potential studies of face and object processing. Vis. Cogn. 3 , 1–38 (1996).

Laganaro, M., Morand, S., Michel, C. M., Spinelli, L. & Schnider, A. ERP correlates of word production before and after stroke in an aphasic patient. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 374–381 (2011).

Indefrey, P. & Levelt, W. J. M. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition 92 , 101–144 (2004).

Valente, A., Burki, A. & Laganaro, M. ERP correlates of word production predictors in picture naming: a trial by trial multiple regression analysis from stimulus onset to response. Front. Neurosci. 8 , 390 (2014).

Kittredge, A. K., Dell, G. S., Verkuilen, J. & Schwartz, M. F. Where is the effect of frequency in word production? Insights from aphasic picture-naming errors. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 25 , 463–492 (2008).

Domdei, N. et al. Ultra-high contrast retinal display system for single photoreceptor psychophysics. Biomed. Opt. Express 9 , 157 (2018).

Poldrack, R. A. et al. Long-term neural and physiological phenotyping of a single human. Nat. Commun. 6 , 8885 (2015).

Coltheart, M. The assumptions of cognitive neuropsychology: reflections on Caramazza (1984, 1986). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 397–402 (2017).

Badecker, W. & Caramazza, A. A final brief in the case against agrammatism: the role of theory in the selection of data. Cognition 24 , 277–282 (1986).

Fischer-Baum, S. Making sense of deviance: Identifying dissociating cases within the case series approach. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 597–617 (2013).

Nickels, L., Howard, D. & Best, W. On the use of different methodologies in cognitive neuropsychology: drink deep and from several sources. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 475–485 (2011).

Dell, G. S. & Schwartz, M. F. Who’s in and who’s out? Inclusion criteria, model evaluation, and the treatment of exceptions in case series. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 515–520 (2011).

Schwartz, M. F. & Dell, G. S. Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 477–494 (2010).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 , 155–159 (1992).

Martin, R. C. & Allen, C. Case studies in neuropsychology. In APA Handbook Of Research Methods In Psychology Vol. 2 Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, And Biological (eds Cooper, H. et al.) 633–646 (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Leivada, E., Westergaard, M., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Rothman, J. On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition: (how) should we proceed? Bilingualism 24 , 197–210 (2021).

Arnett, J. J. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 63 , 602–614 (2008).

Stolz, J. A., Besner, D. & Carr, T. H. Implications of measures of reliability for theories of priming: activity in semantic memory is inherently noisy and uncoordinated. Vis. Cogn. 12 , 284–336 (2005).

Cipora, K. et al. A minority pulls the sample mean: on the individual prevalence of robust group-level cognitive phenomena — the instance of the SNARC effect. Preprint at psyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bwyr3 (2019).

Andrews, S., Lo, S. & Xia, V. Individual differences in automatic semantic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 43 , 1025–1039 (2017).

Tan, L. C. & Yap, M. J. Are individual differences in masked repetition and semantic priming reliable? Vis. Cogn. 24 , 182–200 (2016).

Olsson-Collentine, A., Wicherts, J. M. & van Assen, M. A. L. M. Heterogeneity in direct replications in psychology and its association with effect size. Psychol. Bull. 146 , 922–940 (2020).

Gratton, C. & Braga, R. M. Editorial overview: deep imaging of the individual brain: past, practice, and promise. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , iii–vi (2021).

Fedorenko, E. The early origins and the growing popularity of the individual-subject analytic approach in human neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , 105–112 (2021).

Xue, A. et al. The detailed organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity within the individual. J. Neurophysiol. 125 , 358–384 (2021).

Petit, S. et al. Toward an individualized neural assessment of receptive language in children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63 , 2361–2385 (2020).

Jung, K.-H. et al. Heterogeneity of cerebral white matter lesions and clinical correlates in older adults. Stroke 52 , 620–630 (2021).

Falcon, M. I., Jirsa, V. & Solodkin, A. A new neuroinformatics approach to personalized medicine in neurology: the virtual brain. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 29 , 429–436 (2016).

Duncan, G. J., Engel, M., Claessens, A. & Dowsett, C. J. Replication and robustness in developmental research. Dev. Psychol. 50 , 2417–2425 (2014).

Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 , aac4716 (2015).

Tackett, J. L., Brandes, C. M., King, K. M. & Markon, K. E. Psychology’s replication crisis and clinical psychological science. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15 , 579–604 (2019).

Munafò, M. R. et al. A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1 , 0021 (2017).

Oldfield, R. C. & Wingfield, A. The time it takes to name an object. Nature 202 , 1031–1032 (1964).

Oldfield, R. C. & Wingfield, A. Response latencies in naming objects. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 17 , 273–281 (1965).

Brysbaert, M. How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. J. Cogn. 2 , 16 (2019).

Brysbaert, M. Power considerations in bilingualism research: time to step up our game. Bilingualism https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000437 (2020).

Machery, E. What is a replication? Phil. Sci. 87 , 545–567 (2020).

Nosek, B. A. & Errington, T. M. What is replication? PLoS Biol. 18 , e3000691 (2020).

Li, X., Huang, L., Yao, P. & Hyönä, J. Universal and specific reading mechanisms across different writing systems. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1 , 133–144 (2022).

Rapp, B. (Ed.) The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (Psychology Press, 2001).

Code, C. et al. Classic Cases In Neuropsychology (Psychology Press, 1996).

Patterson, K., Marshall, J. C. & Coltheart, M. Surface Dyslexia: Neuropsychological And Cognitive Studies Of Phonological Reading (Routledge, 2017).

Marshall, J. C. & Newcombe, F. Patterns of paralexia: a psycholinguistic approach. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2 , 175–199 (1973).

Castles, A. & Coltheart, M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition 47 , 149–180 (1993).

Khentov-Kraus, L. & Friedmann, N. Vowel letter dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 35 , 223–270 (2018).

Winskel, H. Orthographic and phonological parafoveal processing of consonants, vowels, and tones when reading Thai. Appl. Psycholinguist. 32 , 739–759 (2011).

Hepner, C., McCloskey, M. & Rapp, B. Do reading and spelling share orthographic representations? Evidence from developmental dysgraphia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 119–143 (2017).

Hanley, J. R. & Sotiropoulos, A. Developmental surface dysgraphia without surface dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 35 , 333–341 (2018).

Zihl, J. & Heywood, C. A. The contribution of single case studies to the neuroscience of vision: single case studies in vision neuroscience. Psych. J. 5 , 5–17 (2016).

Bouvier, S. E. & Engel, S. A. Behavioral deficits and cortical damage loci in cerebral achromatopsia. Cereb. Cortex 16 , 183–191 (2006).

Zihl, J. & Heywood, C. A. The contribution of LM to the neuroscience of movement vision. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9 , 6 (2015).

Dotan, D. & Friedmann, N. Separate mechanisms for number reading and word reading: evidence from selective impairments. Cortex 114 , 176–192 (2019).

McCloskey, M. & Schubert, T. Shared versus separate processes for letter and digit identification. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 31 , 437–460 (2014).

Fayol, M. & Seron, X. On numerical representations. Insights from experimental, neuropsychological, and developmental research. In Handbook of Mathematical Cognition (ed. Campbell, J.) 3–23 (Psychological Press, 2005).

Bornstein, B. & Kidron, D. P. Prosopagnosia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat. 22 , 124–131 (1959).

Kühn, C. D., Gerlach, C., Andersen, K. B., Poulsen, M. & Starrfelt, R. Face recognition in developmental dyslexia: evidence for dissociation between faces and words. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 38 , 107–115 (2021).

Barton, J. J. S., Albonico, A., Susilo, T., Duchaine, B. & Corrow, S. L. Object recognition in acquired and developmental prosopagnosia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 36 , 54–84 (2019).

Renault, B., Signoret, J.-L., Debruille, B., Breton, F. & Bolgert, F. Brain potentials reveal covert facial recognition in prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 27 , 905–912 (1989).

Bauer, R. M. Autonomic recognition of names and faces in prosopagnosia: a neuropsychological application of the guilty knowledge test. Neuropsychologia 22 , 457–469 (1984).

Haan, E. H. F., de, Young, A. & Newcombe, F. Face recognition without awareness. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 4 , 385–415 (1987).

Ellis, H. D. & Lewis, M. B. Capgras delusion: a window on face recognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5 , 149–156 (2001).

Ellis, H. D., Young, A. W., Quayle, A. H. & De Pauw, K. W. Reduced autonomic responses to faces in Capgras delusion. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 264 , 1085–1092 (1997).

Collins, M. N., Hawthorne, M. E., Gribbin, N. & Jacobson, R. Capgras’ syndrome with organic disorders. Postgrad. Med. J. 66 , 1064–1067 (1990).

Enoch, D., Puri, B. K. & Ball, H. Uncommon Psychiatric Syndromes 5th edn (Routledge, 2020).

Tranel, D., Damasio, H. & Damasio, A. R. Double dissociation between overt and covert face recognition. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 7 , 425–432 (1995).

Brighetti, G., Bonifacci, P., Borlimi, R. & Ottaviani, C. “Far from the heart far from the eye”: evidence from the Capgras delusion. Cogn. Neuropsychiat. 12 , 189–197 (2007).

Coltheart, M., Langdon, R. & McKay, R. Delusional belief. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62 , 271–298 (2011).

Coltheart, M. Cognitive neuropsychiatry and delusional belief. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 60 , 1041–1062 (2007).

Coltheart, M. & Davies, M. How unexpected observations lead to new beliefs: a Peircean pathway. Conscious. Cogn. 87 , 103037 (2021).

Coltheart, M. & Davies, M. Failure of hypothesis evaluation as a factor in delusional belief. Cogn. Neuropsychiat. 26 , 213–230 (2021).

McCloskey, M. et al. A developmental deficit in localizing objects from vision. Psychol. Sci. 6 , 112–117 (1995).

McCloskey, M., Valtonen, J. & Cohen Sherman, J. Representing orientation: a coordinate-system hypothesis and evidence from developmental deficits. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 23 , 680–713 (2006).

McCloskey, M. Spatial representations and multiple-visual-systems hypotheses: evidence from a developmental deficit in visual location and orientation processing. Cortex 40 , 677–694 (2004).

Gregory, E. & McCloskey, M. Mirror-image confusions: implications for representation and processing of object orientation. Cognition 116 , 110–129 (2010).

Gregory, E., Landau, B. & McCloskey, M. Representation of object orientation in children: evidence from mirror-image confusions. Vis. Cogn. 19 , 1035–1062 (2011).

Laine, M. & Martin, N. Cognitive neuropsychology has been, is, and will be significant to aphasiology. Aphasiology 26 , 1362–1376 (2012).

Howard, D. & Patterson, K. The Pyramids And Palm Trees Test: A Test Of Semantic Access From Words And Pictures (Thames Valley Test Co., 1992).

Kay, J., Lesser, R. & Coltheart, M. PALPA: Psycholinguistic Assessments Of Language Processing In Aphasia. 2: Picture & Word Semantics, Sentence Comprehension (Erlbaum, 2001).

Franklin, S. Dissociations in auditory word comprehension; evidence from nine fluent aphasic patients. Aphasiology 3 , 189–207 (1989).

Howard, D., Swinburn, K. & Porter, G. Putting the CAT out: what the comprehensive aphasia test has to offer. Aphasiology 24 , 56–74 (2010).

Conti-Ramsden, G., Crutchley, A. & Botting, N. The extent to which psychometric tests differentiate subgroups of children with SLI. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 40 , 765–777 (1997).

Bishop, D. V. M. & McArthur, G. M. Individual differences in auditory processing in specific language impairment: a follow-up study using event-related potentials and behavioural thresholds. Cortex 41 , 327–341 (2005).

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A. & Greenhalgh, T., and the CATALISE-2 consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: terminology. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 58 , 1068–1080 (2017).

Wilson, A. J. et al. Principles underlying the design of ‘the number race’, an adaptive computer game for remediation of dyscalculia. Behav. Brain Funct. 2 , 19 (2006).

Basso, A. & Marangolo, P. Cognitive neuropsychological rehabilitation: the emperor’s new clothes? Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 10 , 219–229 (2000).

Murad, M. H., Asi, N., Alsawas, M. & Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. Evidence-based Med. 21 , 125–127 (2016).

Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J. & Maskrey, N., for the Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? Br. Med. J. 348 , g3725–g3725 (2014).

Best, W., Ping Sze, W., Edmundson, A. & Nickels, L. What counts as evidence? Swimming against the tide: valuing both clinically informed experimentally controlled case series and randomized controlled trials in intervention research. Evidence-based Commun. Assess. Interv. 13 , 107–135 (2019).

Best, W. et al. Understanding differing outcomes from semantic and phonological interventions with children with word-finding difficulties: a group and case series study. Cortex 134 , 145–161 (2021).

OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. CEBM https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (2011).

Holler, D. E., Behrmann, M. & Snow, J. C. Real-world size coding of solid objects, but not 2-D or 3-D images, in visual agnosia patients with bilateral ventral lesions. Cortex 119 , 555–568 (2019).

Duchaine, B. C., Yovel, G., Butterworth, E. J. & Nakayama, K. Prosopagnosia as an impairment to face-specific mechanisms: elimination of the alternative hypotheses in a developmental case. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 23 , 714–747 (2006).

Hartley, T. et al. The hippocampus is required for short-term topographical memory in humans. Hippocampus 17 , 34–48 (2007).

Pishnamazi, M. et al. Attentional bias towards and away from fearful faces is modulated by developmental amygdala damage. Cortex 81 , 24–34 (2016).

Rapp, B., Fischer-Baum, S. & Miozzo, M. Modality and morphology: what we write may not be what we say. Psychol. Sci. 26 , 892–902 (2015).

Yong, K. X. X., Warren, J. D., Warrington, E. K. & Crutch, S. J. Intact reading in patients with profound early visual dysfunction. Cortex 49 , 2294–2306 (2013).

Rockland, K. S. & Van Hoesen, G. W. Direct temporal–occipital feedback connections to striate cortex (V1) in the macaque monkey. Cereb. Cortex 4 , 300–313 (1994).

Haynes, J.-D., Driver, J. & Rees, G. Visibility reflects dynamic changes of effective connectivity between V1 and fusiform cortex. Neuron 46 , 811–821 (2005).

Tanaka, K. Mechanisms of visual object recognition: monkey and human studies. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7 , 523–529 (1997).

Fischer-Baum, S., McCloskey, M. & Rapp, B. Representation of letter position in spelling: evidence from acquired dysgraphia. Cognition 115 , 466–490 (2010).

Houghton, G. The problem of serial order: a neural network model of sequence learning and recall. In Current Research In Natural Language Generation (eds Dale, R., Mellish, C. & Zock, M.) 287–319 (Academic Press, 1990).

Fieder, N., Nickels, L., Biedermann, B. & Best, W. From “some butter” to “a butter”: an investigation of mass and count representation and processing. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 31 , 313–349 (2014).

Fieder, N., Nickels, L., Biedermann, B. & Best, W. How ‘some garlic’ becomes ‘a garlic’ or ‘some onion’: mass and count processing in aphasia. Neuropsychologia 75 , 626–645 (2015).

Schröder, A., Burchert, F. & Stadie, N. Training-induced improvement of noncanonical sentence production does not generalize to comprehension: evidence for modality-specific processes. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 195–220 (2015).

Stadie, N. et al. Unambiguous generalization effects after treatment of non-canonical sentence production in German agrammatism. Brain Lang. 104 , 211–229 (2008).

Schapiro, A. C., Gregory, E., Landau, B., McCloskey, M. & Turk-Browne, N. B. The necessity of the medial temporal lobe for statistical learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26 , 1736–1747 (2014).

Schapiro, A. C., Kustner, L. V. & Turk-Browne, N. B. Shaping of object representations in the human medial temporal lobe based on temporal regularities. Curr. Biol. 22 , 1622–1627 (2012).

Baddeley, A., Vargha-Khadem, F. & Mishkin, M. Preserved recognition in a case of developmental amnesia: implications for the acaquisition of semantic memory? J. Cogn. Neurosci. 13 , 357–369 (2001).

Snyder, J. J. & Chatterjee, A. Spatial-temporal anisometries following right parietal damage. Neuropsychologia 42 , 1703–1708 (2004).

Ashkenazi, S., Henik, A., Ifergane, G. & Shelef, I. Basic numerical processing in left intraparietal sulcus (IPS) acalculia. Cortex 44 , 439–448 (2008).

Lebrun, M.-A., Moreau, P., McNally-Gagnon, A., Mignault Goulet, G. & Peretz, I. Congenital amusia in childhood: a case study. Cortex 48 , 683–688 (2012).

Vannuscorps, G., Andres, M. & Pillon, A. When does action comprehension need motor involvement? Evidence from upper limb aplasia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 253–283 (2013).

Jeannerod, M. Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. NeuroImage 14 , S103–S109 (2001).

Blakemore, S.-J. & Decety, J. From the perception of action to the understanding of intention. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 , 561–567 (2001).

Rizzolatti, G. & Craighero, L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27 , 169–192 (2004).

Forde, E. M. E., Humphreys, G. W. & Remoundou, M. Disordered knowledge of action order in action disorganisation syndrome. Neurocase 10 , 19–28 (2004).

Mazzi, C. & Savazzi, S. The glamor of old-style single-case studies in the neuroimaging era: insights from a patient with hemianopia. Front. Psychol. 10 , 965 (2019).

Coltheart, M. What has functional neuroimaging told us about the mind (so far)? (Position Paper Presented to the European Cognitive Neuropsychology Workshop, Bressanone, 2005). Cortex 42 , 323–331 (2006).

Page, M. P. A. What can’t functional neuroimaging tell the cognitive psychologist? Cortex 42 , 428–443 (2006).

Blank, I. A., Kiran, S. & Fedorenko, E. Can neuroimaging help aphasia researchers? Addressing generalizability, variability, and interpretability. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 377–393 (2017).

Niv, Y. The primacy of behavioral research for understanding the brain. Behav. Neurosci. 135 , 601–609 (2021).

Crawford, J. R. & Howell, D. C. Comparing an individual’s test score against norms derived from small samples. Clin. Neuropsychol. 12 , 482–486 (1998).

Crawford, J. R., Garthwaite, P. H. & Ryan, K. Comparing a single case to a control sample: testing for neuropsychological deficits and dissociations in the presence of covariates. Cortex 47 , 1166–1178 (2011).

McIntosh, R. D. & Rittmo, J. Ö. Power calculations in single-case neuropsychology: a practical primer. Cortex 135 , 146–158 (2021).

Patterson, K. & Plaut, D. C. “Shallow draughts intoxicate the brain”: lessons from cognitive science for cognitive neuropsychology. Top. Cogn. Sci. 1 , 39–58 (2009).

Lambon Ralph, M. A., Patterson, K. & Plaut, D. C. Finite case series or infinite single-case studies? Comments on “Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology” by Schwartz and Dell (2010). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 466–474 (2011).

Horien, C., Shen, X., Scheinost, D. & Constable, R. T. The individual functional connectome is unique and stable over months to years. NeuroImage 189 , 676–687 (2019).

Epelbaum, S. et al. Pure alexia as a disconnection syndrome: new diffusion imaging evidence for an old concept. Cortex 44 , 962–974 (2008).

Fischer-Baum, S. & Campana, G. Neuroplasticity and the logic of cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 403–411 (2017).

Paul, S., Baca, E. & Fischer-Baum, S. Cerebellar contributions to orthographic working memory: a single case cognitive neuropsychological investigation. Neuropsychologia 171 , 108242 (2022).

Feinstein, J. S., Adolphs, R., Damasio, A. & Tranel, D. The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear. Curr. Biol. 21 , 34–38 (2011).

Crawford, J., Garthwaite, P. & Gray, C. Wanted: fully operational definitions of dissociations in single-case studies. Cortex 39 , 357–370 (2003).

McIntosh, R. D. Simple dissociations for a higher-powered neuropsychology. Cortex 103 , 256–265 (2018).

McIntosh, R. D. & Brooks, J. L. Current tests and trends in single-case neuropsychology. Cortex 47 , 1151–1159 (2011).

Best, W., Schröder, A. & Herbert, R. An investigation of a relative impairment in naming non-living items: theoretical and methodological implications. J. Neurolinguistics 19 , 96–123 (2006).

Franklin, S., Howard, D. & Patterson, K. Abstract word anomia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 12 , 549–566 (1995).

Coltheart, M., Patterson, K. E. & Marshall, J. C. Deep Dyslexia (Routledge, 1980).

Nickels, L., Kohnen, S. & Biedermann, B. An untapped resource: treatment as a tool for revealing the nature of cognitive processes. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 539–562 (2010).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of those pioneers of and advocates for single case study research who have mentored, inspired and encouraged us over the years, and the many other colleagues with whom we have discussed these issues.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychological Sciences & Macquarie University Centre for Reading, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Lyndsey Nickels

NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Aphasia Recovery and Rehabilitation, Australia

Psychological Sciences, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA

Simon Fischer-Baum

Psychology and Language Sciences, University College London, London, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.N. led and was primarily responsible for the structuring and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lyndsey Nickels .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Yanchao Bi, Rob McIntosh, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nickels, L., Fischer-Baum, S. & Best, W. Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories. Nat Rev Psychol 1 , 733–747 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00127-y

Download citation

Accepted : 13 October 2022

Published : 22 November 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00127-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- CREd Library , Research Design and Method

Issues In Single-Subject Research

Kevin p kearns.

- March, 2011

DOI: 10.1044/cred-ssd-ps-cpri005

The following slides accompanied a presentation delivered at ASHA’s Clinical Practice Research Institute.

Data speak, not men…

“Designs have inherent rigor but not all studies using a design are rigorous” — Randy; yesterday

“Illusion of strong evidence…”– Gilbert, McPeek & Mosteller, 1977

Effects of Interpretation Bias on Research Evidence (Kaptchuk, 2003)

- “Good science inevitably embodies a tension between the empiricism of concrete data and the rationalism of deeply held convictions.”

- “…a view that science is totally objective is mythical and ignores the human element.”

Single-Subject Designs: Introduction

- Single subject experimental designs are among the most prevalent used in SLP treatment research. — (Kearns & Thompson, 1991; Thompson, 2006; Schlosser et al, 2004)

- Well designed single subject design studies are now commonly published in our journals as well as in interdisciplinary specialty journals — (Psychology, Neuropsychology, Education , PT, OT…)

- Agencies, including NIH, NIDDR etc., commonly fund conceptually salient and well designed single subject design treatment programs — (Aphasia, AAC, autism…)

- Meta-analyses have been employed to examine the overall impact of single subject studies on the efficacy and efficiency of interventions — (Robey et al., 1999)

- Quality indicators for single-subject designs appear to be less well understood than for group designs (Kratochwill & Stoiber, 2002; APA Div. 12; Horner, Carr, Halle, et al, 2005).

- Common threats to internal and external validity persist in our despite readily available solutions. (Schlosser, 2004; Thomson, 2006)

- Brief introduction to single subject designs

- Identify elements of single designs that contribute to problems with internal validity/experimental control from a reviewer’s perspective

- Discuss solutions for some of these issues; ultimately necessary for publication and external funding

Common Single-Subject Design Strategies

- Single-subject designs are experimental, not observational.

- Subjects “serve as their own controls”; receive both treatment and no-treatment conditions

- Juxtaposition of Baseline (A) phases with Treatment (B) phases provides mechanism for experimental control (internal validity)

- Control is based on within and across subject replication

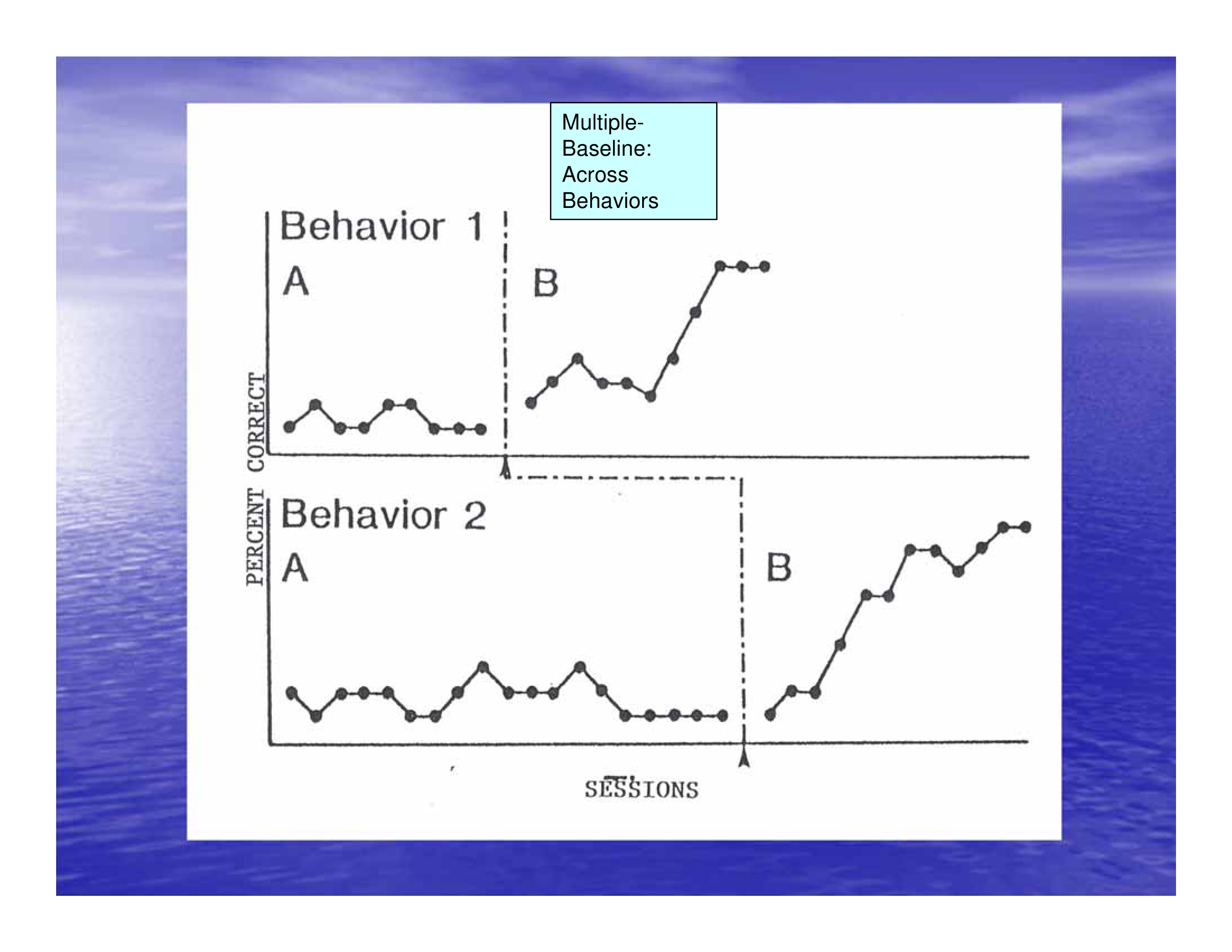

Multiple- Baseline: Across Behaviors

Treatment vs No-treatment comparisons

- Examine efficacy of treatment relative to no treatment

- Multiple baselines/ variants; Withdrawal/ reversals

Component Assessment

- Relative contribution of treatment components

- Interaction Designs (variant of reversals)

Successive Level Analysis

- Examine successive levels of treatment

- Multiple Probe; Changing Criterion

Treatment – Treatment Comparisons

- Alternating Treatments (mixed m b )

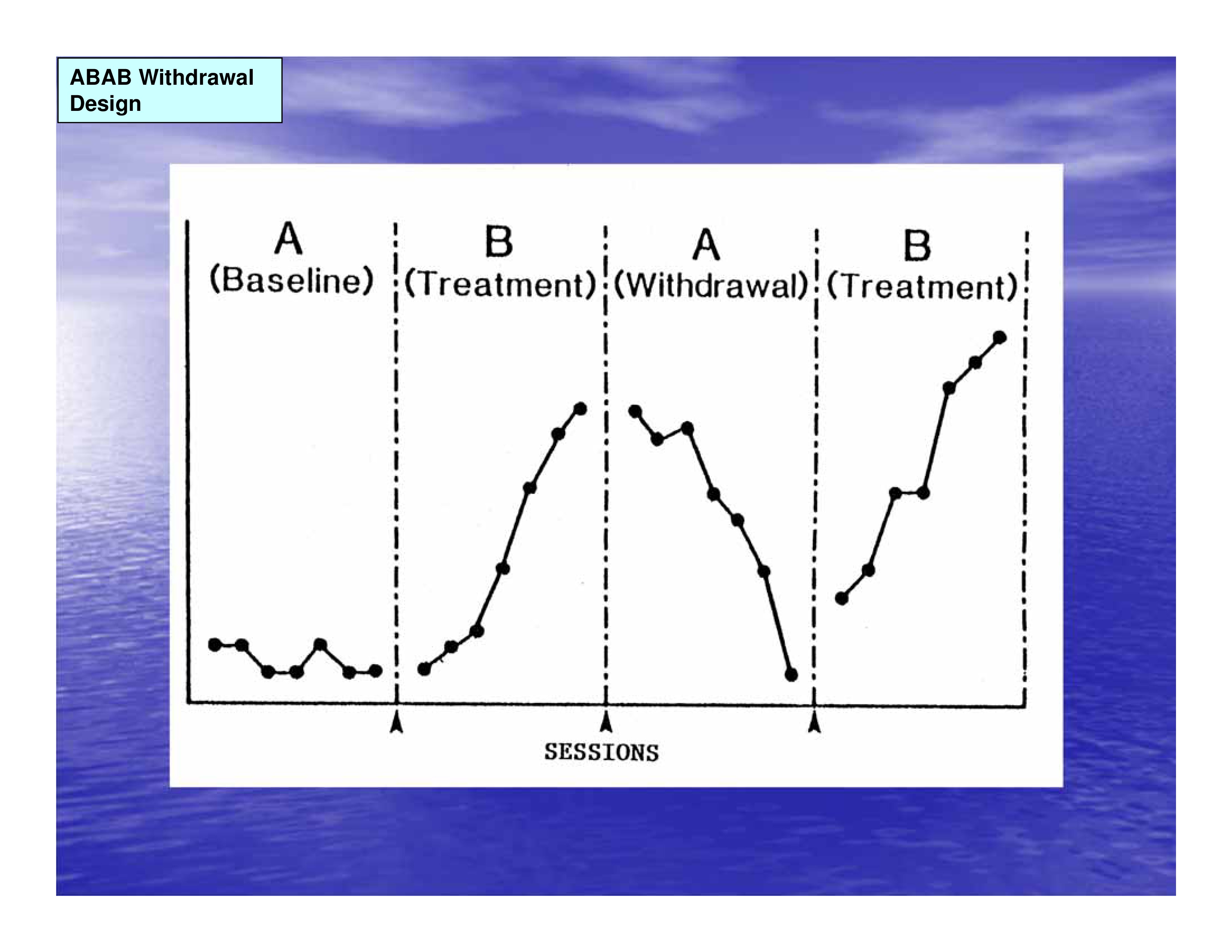

ABAB Withdrawal Design

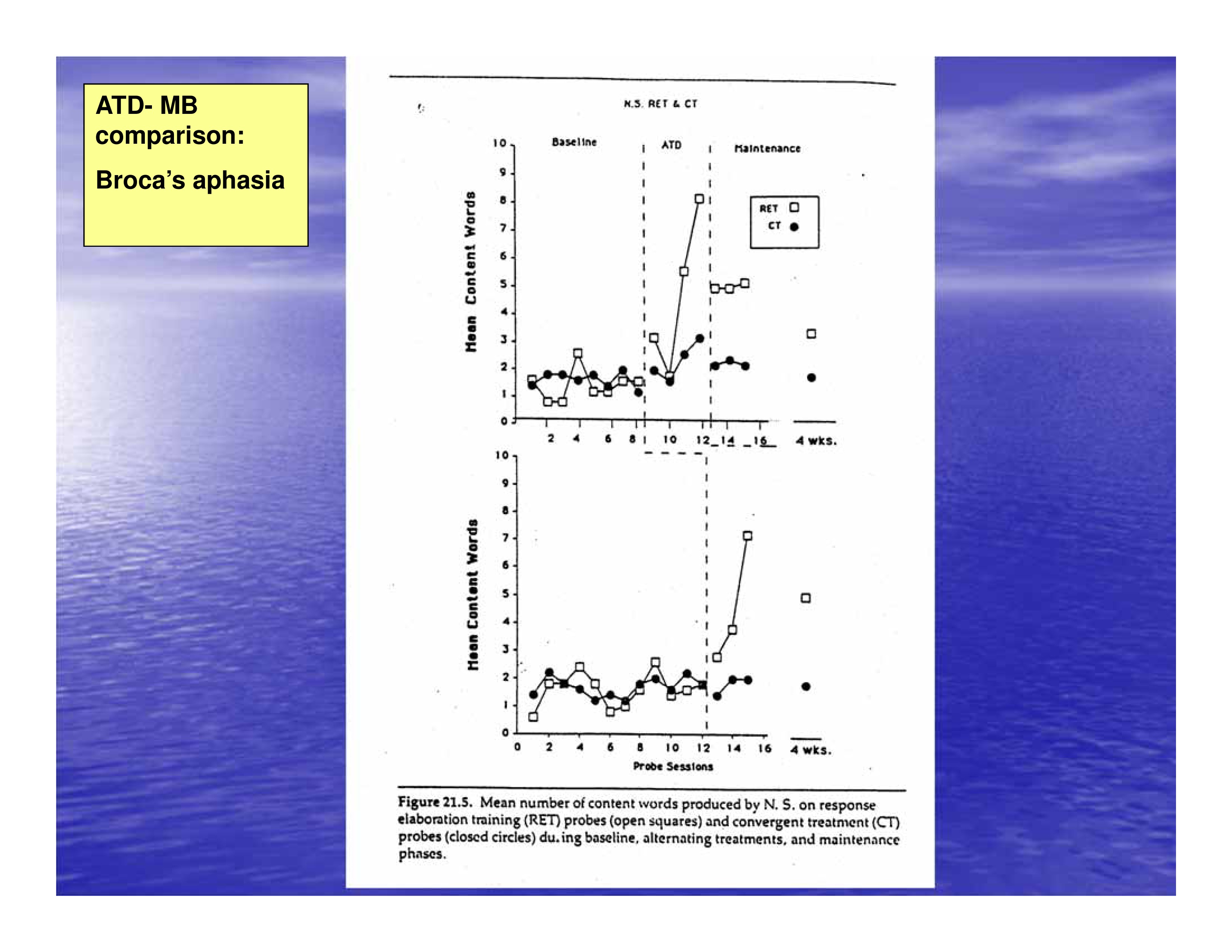

ATD-MB comparison: Broca’s aphasia

Internal Validity

- Operational specificity; reliability of IV, DV; treatment integrity; appropriate design

- Artifact, Bias

- Visual analysis of ‘control’: Loss of baseline (unstable; drifting trend); W/I and across phase changes: Level, Slope, Trend

- Replicated treatment effects: three demonstrations of the effect at three points in time

Visual-Graphic Analysis

- Level (on the ordinate; %..)

- Slope (stable, increasing, decreasing)

- Trend over time (variable; changes with phases; overlapping.)

- Overlap, immediacy of effect, similarity of effect for similar phases

- Correlation of change and phase change

Research on Visual Inspection of Single-Subject Data (Franklin et al, 1996; Robey et al, 1999)

- Low level of inter-rater agreement: De Prospero & Cohen (1979) Reported R = .61 among behavioral journal reviewers

- Reliability and validity of visual inspection can be improved with training (Hagopian et al, 1997)

- Visual aids (trend lines) may have produced only modest increase in reliability

- Traditional statistical analyses (eg. Binomial test) are highly affected by serial dependence (Crosbie, 1993)

Serial Dependence/Autocorrelation

- The level of behavior at one point in time is influenced by or correlated with the level of behavior at another point in time

- Autocorrelation biases interpretation and leads to Type I errors (falsely concluding a treatment effect exists; positive autocorrelation) and Type II errors (falsely concluding no treatment effect; negative autocorrelation)

- Independence assumption

- ITSACORR: A statistical procedure that controls for autocorrelation (Crosbie, 1993)

- Visual Inspection and Structured Criteria (Fisher, Kelley & Lomas, 2003; JABA)

- SMA bootstrapping approach (Borckardt, et al, 2008; AM Psychologist)

- clinicalresearcher.org

Baseline Measures

- Randomize order or stimulus sets/ conditions

- All treatment stimuli need to be assessed in baseline

- Establish equivalence for subsets of stimuli used as representative

- Avoid false baselines

- A priori stability decisions greatly reduce bias

- At least 7 baseline probes may be needed for reliable and valid visual analysis

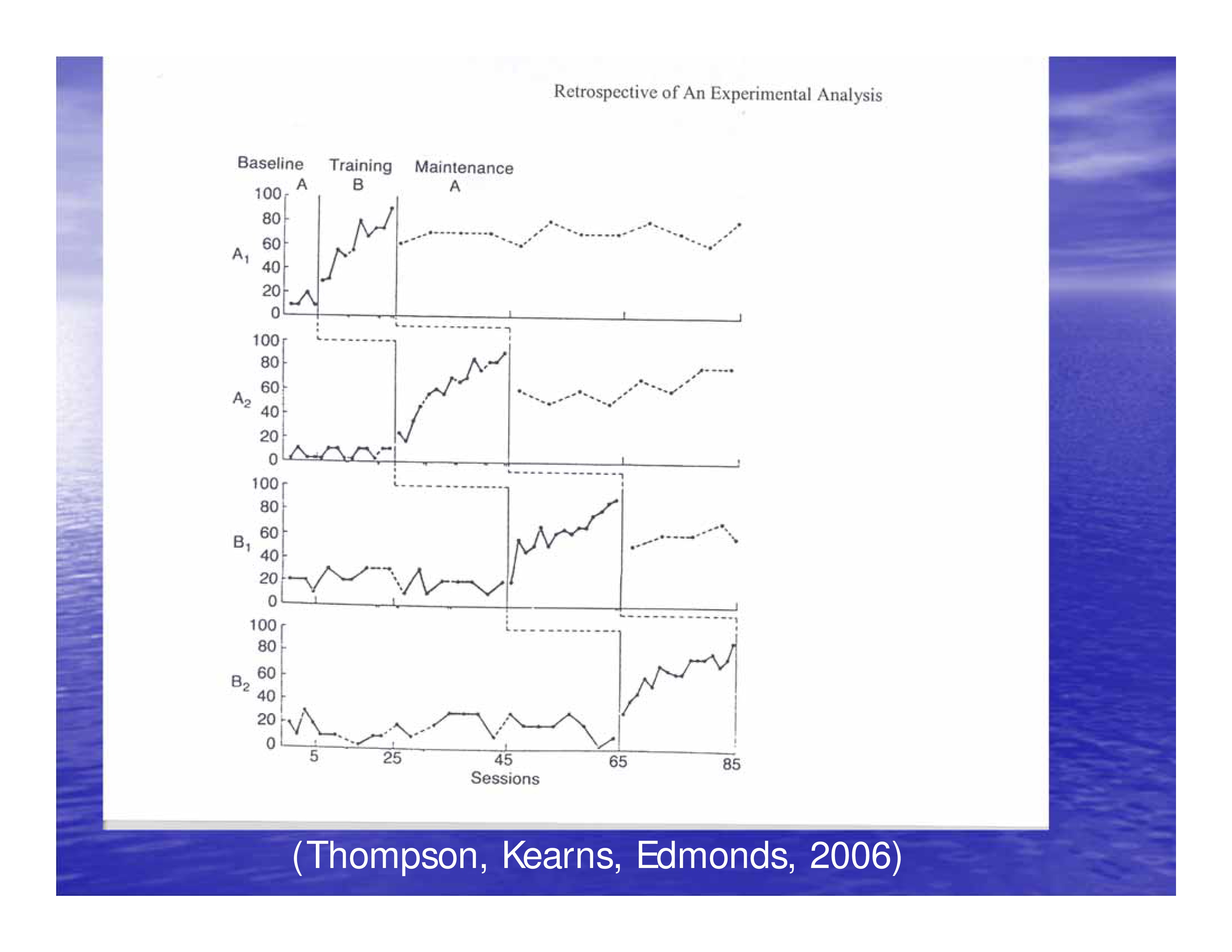

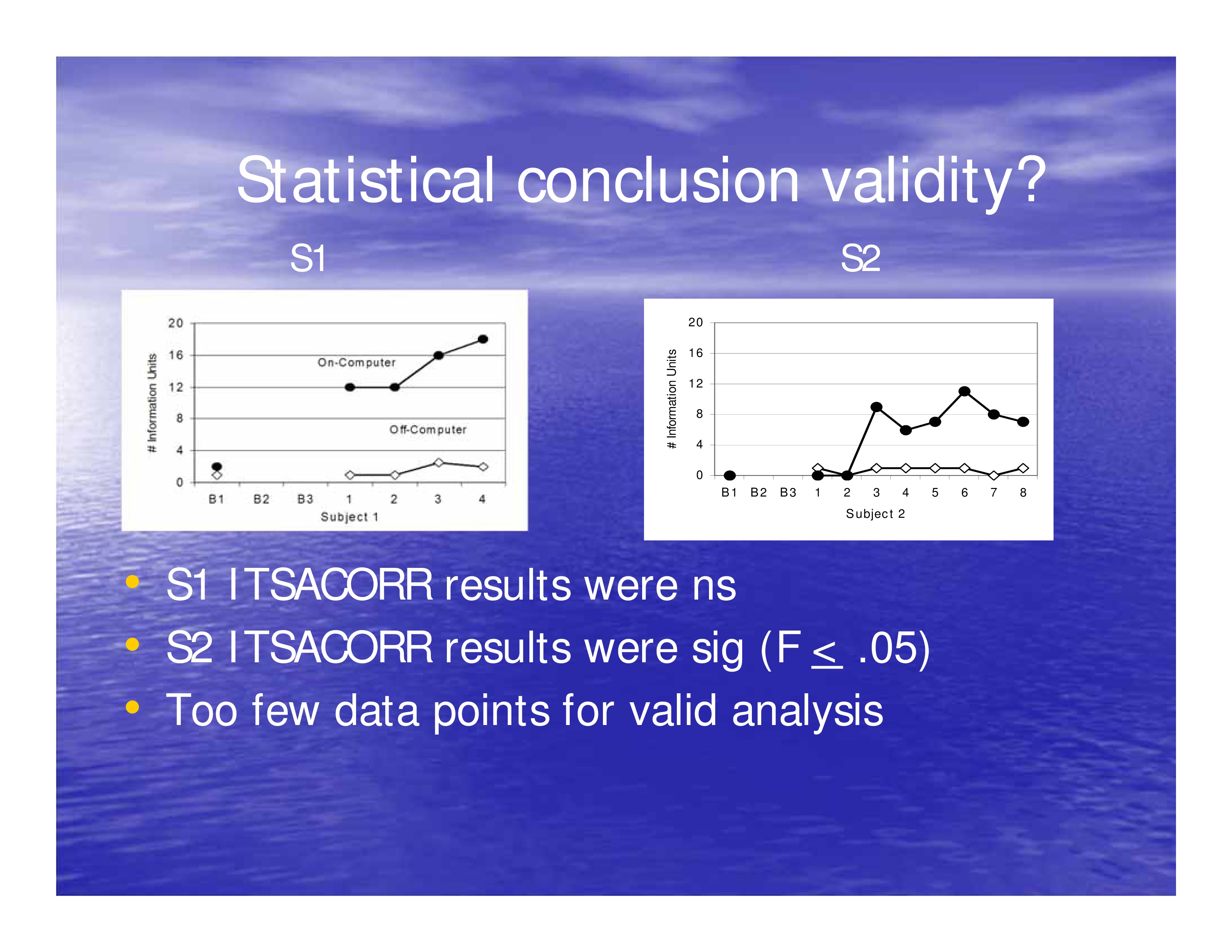

S1 ITSACORR results were non-significant

S2 ITSACORR results were sig (F < .05)

Too few data points for valid analysis

Intervention

- Explicit steps; directions….a Manual

- Control for order effects

- Assess integrity of intervention (see Schlosser, 2004)

- One variable rule

- Is treatment intensity: sufficient; typical?

- Performance level (e.g. % correct)

- Maximum allowable length of treatment (but not equal phases)

Dependent Measures

- Use multiple measures

- Try not to collect during treatment sessions

- Probe often (weekly or more)

- Pre-train assistants the scoring code and periodically check for ‘drift’

- Are definitions specific, observable and replicable?

Reliability

- Reliability for both intervention and dependent variable

- Obtain for each phase of the study and adequately sample

- Control for sources of bias including drift and expectancy (ABCs — artifact, bias, and complexity)

- Use point to point reliability when possible

- Calculate probability of chance agreement; critical for periods of high or low responding

- Occurrence and non occurrence reliability

A priori Decisions

Failure to establish and make explicit criteria for guiding procedural and methodological decisions prior to change is a serious threat to internal validity that is difficult.

- Participant selection/ exclusion criteria (report attrition)

- Baseline variability, length

- Phase changes

- Clinical significance

- Generalization

Consider Clinically Meaningful Change

Clinical significance can not be assumed from our perspective alone.

Change in level of performance on any outcome measure, even when effects are large and visually obvious or significant, is an insufficient metric of the impact of experimental treatment on our participants/ patients.

Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) : “the smallest difference in a score that is considered worthwhile or important” (Hays & Woolley, 2000)

Responsiveness of Health Measures (Husted et al., 2000) 1. Distribution based approaches examine internal responsiveness, using distribution/ variability of initial (baseline) scores to examine differences (e.g. Effect size).

2. Anchor based approaches examine external responsiveness by comparing change detected by a dependent measure with an external criterion. For example, specify a level of change that meets “minimal clinically important difference” (MCID).

Anchor-based Responsiveness measures (see Beninato, et al Archives of PMR, 2006) use external criterion as “anchor”

- Compare change score on outcome measure to some other estimate of important change

- Patient’s/Family estimates

- Clinician’s estimates

- Necessary to complete the EBP triangle?

Revisiting Clinically Important Change (Social Validation)

When the perceived change is important to the patient, clinician, researcher, payor or society (Beaton et al., 2001)

Requires that we extend our conceptual frame of reference beyond typical outcome measures and distribution based measures of responsiveness

“Time will tell” — (M. Planck, 1950)

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die.” — (Kaptchuk, 2003)

Franklin, R. D., Gorman, B. S., Beasley, T. M. & Allison, D. B. (1996). Graphical display and visual analysis.. Design and Snalysis of Single-Case Research , (pp. 119–158). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kearns, K. P. & Thompson, C. K. (1991). Technical drift and conceptual myopia: The Merlin effect. Clinical Aphasiology , 19, 31–40

Kevin P Kearns SUNY Fredonia

Presented at the Clinical Practice Research Institute (CPRI). Hosted by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Research Mentoring Network.

Copyrighted Material. Reproduced by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in the Clinical Research Education Library with permission from the author or presenter.

Clinical Research Education

More from the cred library, innovative treatments for persons with dementia, implementation science resources for crisp, when the ears interact with the brain, follow asha journals on twitter.

© 1997-2024 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Privacy Notice Terms of Use

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias