What is Theme? A Look at 20 Common Themes in Literature

Sean Glatch | August 28, 2023 | 18 Comments

When someone asks you “What is this book about?” , there are a few ways you can answer. There’s “ plot ,” which refers to the literal events in the book, and there’s “character,” which refers to the people in the book and the struggles they overcome. Finally, there are themes in literature that correspond with the work’s topic and message. But what is theme in literature?

The theme of a story or poem refers to the deeper meaning of that story or poem. All works of literature contend with certain complex ideas, and theme is how a story or poem approaches these ideas.

There are countless ways to approach the theme of a story or poem, so let’s take a look at some theme examples and a list of themes in literature. We’ll discuss the differences between theme and other devices, like theme vs moral and theme vs topic. Finally, we’ll examine why theme is so essential to any work of literature, including to your own writing.

But first, what is theme? Let’s explore what theme is—and what theme isn’t.

- Theme Definition

20 Common Themes in Literature

- Theme Examples

Themes in Literature: A Hierarchy of Ideas

Why themes in literature matter.

- Should I Decide the Themes of a Story in Advance?

Theme Definition: What is Theme?

Theme describes the central idea(s) that a piece of writing explores. Rather than stating this theme directly, the author will look at theme using the set of literary tools at their disposal. The theme of a story or poem will be explored through elements like characters , plot, settings , conflict, and even word choice and literary devices .

Theme definition: the central idea(s) that a piece of writing explores.

That said, theme is more than just an idea. It is also the work’s specific vantage point on that idea. In other words, a theme is an idea plus an opinion: it is the author’s specific views regarding the central ideas of the work.

All works of literature have these central ideas and opinions, even if those ideas and opinions aren’t immediate to the reader.

Justice, for example, is a literary theme that shows up in a lot of classical works. To Kill a Mockingbird contends with racial justice, especially at a time when the U.S. justice system was exceedingly stacked against African Americans. How can a nation call itself just when justice is used as a weapon?

By contrast, the play Hamlet is about the son of a recently-executed king. Hamlet seeks justice for his father and vows to kill Claudius—his father’s killer—but routinely encounters the paradox of revenge. Can justice really be found through more bloodshed?

What is theme? An idea + an opinion.

Clearly, these two works contend with justice in unrelated ways. All themes in literature are broad and open-ended, allowing writers to explore their own ideas about these complex topics.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

30 Poems in 30 Days

with Ollie Schminkey

April 1st, 2024

This National Poetry Writing Month (NaPoWriMo), build community and get feedback on your work while writing a poem every day.

The Heart Remembers: Writing About Loss

with Charlotte Maya

April 3rd, 2024

How can we organize grief and loss into language? Honor your feelings and write moving essays in this heart-centered creative nonfiction class.

Let It Rip: The Art of Writing Fiery Prose

with Giulietta Nardone

You'll write prose that gets folks so hot and bothered they won't be able to put it down, even if it isn't about sex.

Write Your Novel! The Workshop With Jack

with Jack Smith

Get a good start on a novel in just ten weeks, or revise a novel you’ve already written. Free your imagination, move steadily ahead and count the pages!

Writing the Body: A Nonfiction Craft Seminar

with Margo Steines

April 9th, 2024

The weird and wild body is a rich site of exploration in creative nonfiction. Explore the questions, stories, and lessons your body holds in this seminar with Margo Steines.

Let’s look at some common themes in literature. The ideas presented within this list of themes in literature show up in novels, memoirs, poems, and stories throughout history.

Theme Examples in Literature

Let’s take a closer look at how writers approach and execute theme. Themes in literature are conveyed throughout the work, so while you might not have read the books in the following theme examples, we’ve provided plot synopses and other relevant details where necessary. We analyze the following:

- Power and Corruption in the novel Animal Farm

- Loneliness in the short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

- Love in the poem “How Do I Love Thee”

Theme Examples: Power and Corruption in the Novel Animal Farm

At its simplest, the novel Animal Farm by George Orwell is an allegory that represents the rise and moral decline of Communism in Russia. Specifically, the novel uncovers how power corrupts the leaders of populist uprisings, turning philosophical ideals into authoritarian regimes.

Most of the characters in Animal Farm represent key figures during and after the Russian Revolution. On an ailing farm that’s run by the negligent farmer Mr. Jones (Tsar Nicholas II), the livestock are ready to seize control of the land. The livestock’s discontent is ripened by Old Major (Karl Marx/Lenin), who advocates for the overthrow of the ruling elite and the seizure of private land for public benefit.

After Old Major dies, the pigs Napoleon (Joseph Stalin) and Snowball (Leon Trotsky) stage a revolt. Mr. Jones is chased off the land, which parallels the Russian Revolution in 1917. The pigs then instill “Animalism”—a system of government that advocates for the rights of the common animal. At the core of this philosophy is the idea that “all animals are equal”—an ideal that, briefly, every animal upholds.

Initially, the Animalist Revolution brings peace and prosperity to the farm. Every animal is well-fed, learns how to read, and works for the betterment of the community. However, when Snowball starts implementing a plan to build a windmill, Napoleon drives Snowball off of the farm, effectively assuming leadership over the whole farm. (In real life, Stalin forced Trotsky into exile, and Trotsky spent the rest of his life critiquing the Stalin regime until he was assassinated in 1940.)

Napoleon’s leadership quickly devolves into demagoguery, demonstrating the corrupting influence of power and the ways that ideology can breed authoritarianism. Napoleon uses Snowball as a scapegoat for whenever the farm has a setback, while using Squealer (Vyacheslav Molotov) as his private informant and public orator.

Eventually, Napoleon changes the tenets of Animalism, starts walking on two legs, and acquires other traits and characteristics of humans. At the end of the novel, and after several more conflicts , purges, and rule changes, the livestock can no longer tell the difference between the pigs and humans.

Themes in Literature: Power and Corruption in Animal Farm

So, how does Animal Farm explore the theme of “Power and Corruption”? Let’s analyze a few key elements of the novel.

Plot: The novel’s major plot points each relate to power struggles among the livestock. First, the livestock wrest control of the farm from Mr. Jones; then, Napoleon ostracizes Snowball and turns him into a scapegoat. By seizing leadership of the farm for himself, Napoleon grants himself massive power over the land, abusing this power for his own benefit. His leadership brings about purges, rule changes, and the return of inequality among the livestock, while Napoleon himself starts to look more and more like a human—in other words, he resembles the demagoguery of Mr. Jones and the abuse that preceded the Animalist revolution.

Thus, each plot point revolves around power and how power is wielded by corrupt leadership. At its center, the novel warns the reader of unchecked power, and how corrupt leaders will create echo chambers and private militaries in order to preserve that power.

Characters: The novel’s characters reinforce this message of power by resembling real life events. Most of these characters represent real life figures from the Russian Revolution, including the ideologies behind that revolution. By creating an allegory around Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and the other leading figures of Communist Russia’s rise and fall, the novel reminds us that unchecked power foments disaster in the real world.

Literary Devices: There are a few key literary devices that support the theme of Power and Corruption. First, the novel itself is a “satirical allegory.” “ Satire ” means that the novel is ridiculing the behaviors of certain people—namely Stalin, who instilled far-more-dangerous laws and abuses that created further inequality in Russia/the U.S.S.R. While Lenin and Trotsky had admirable goals for the Russian nation, Stalin is, quite literally, a pig.

Meanwhile, “allegory” means that the story bears symbolic resemblance to real life, often to teach a moral. The characters and events in this story resemble the Russian Revolution and its aftermath, with the purpose of warning the reader about unchecked power.

Finally, an important literary device in Animal Farm is symbolism . When Napoleon (Stalin) begins to resemble a human, the novel suggests that he has become as evil and negligent as Mr. Jones (Tsar Nicholas II). Since the Russian Revolution was a rejection of the Russian monarchy, equating Stalin to the monarchy reinforces the corrupting influence of power, and the need to elect moral individuals to posts of national leadership.

Theme Examples: Loneliness in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Ernest Hemingway’s short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” is concerned with the theme of loneliness. You can read this short story here . Content warning for mentions of suicide.

There are very few plot points in Hemingway’s story, so most of the story’s theme is expressed through dialogue and description. In the story, an old man stays up late drinking at a cafe. The old man has no wife—only a niece that stays with him—and he attempted suicide the previous week. Two waiters observe him: a younger waiter wants the old man to leave so they can close the cafe, while an older waiter sympathizes with the old man. None of these characters have names.

The younger waiter kicks out the old man and closes the cafe. The older waiter walks to a different cafe and ruminates on the importance of “a clean, well-lighted place” like the cafe he works at.

Themes in Literature: Loneliness in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Hemingway doesn’t tell us what to think about the old man’s loneliness, but he does provide two opposing viewpoints through the dialogue of the waiters.

The younger waiter has the hallmarks of a happy life: youth, confidence, and a wife to come home to. While he acknowledges that the old man is unhappy, he also admits “I don’t want to look at him,” complaining that the old man has “no regard for those who must work.” The younger waiter “did not wish to be unjust,” he simply wanted to return home.

The older waiter doesn’t have the privilege of turning away: like the old man, he has a house but not a home to return to, and he knows that someone may need the comfort of “a clean and pleasant cafe.”

The older waiter, like Hemingway, empathizes with the plight of the old man. When your place of rest isn’t a home, the world can feel like a prison, so having access to a space that counteracts this feeling is crucial. What kind of a place is that? The older waiter surmises that “the light of course” matters, but the place must be “clean and pleasant” too. Additionally, the place should not have music or be a bar: it must let you preserve the quiet dignity of yourself.

Lastly, the older waiter’s musings about God clue the reader into his shared loneliness with the old man. In a stream of consciousness, the older waiter recites traditional Christian prayers with “nada” in place of “God,” “Father,” “Heaven,” and other symbols of divinity. A bartender describes the waiter as “otro locos mas” (translation: another crazy), and the waiter concludes that his plight must be insomnia.

This belies the irony of loneliness: only the lonely recognize it. The older waiter lacks confidence, youth, and belief in a greater good. He recognizes these traits in the old man, as they both share a need for a clean, well-lighted place long after most people fall asleep. Yet, the younger waiter and the bartender don’t recognize these traits as loneliness, just the ramblings and shortcomings of crazy people.

Does loneliness beget craziness? Perhaps. But to call the waiter and old man crazy would dismiss their feelings and experiences, further deepening their loneliness.

Loneliness is only mentioned once in the story, when the young waiter says “He’s [the old man] lonely. I’m not lonely. I have a wife waiting in bed for me.” Nonetheless, loneliness consumes this short story and its older characters, revealing a plight that, ironically, only the lonely understand.

Theme Examples: Love in the Poem “How Do I Love Thee”

Let’s turn towards brighter themes in literature: namely, love in poetry . Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “ How Do I Love Thee ” is all about the theme of love.

Themes in Literature: Love in “How Do I Love Thee”

Browning’s poem is a sonnet , which is a 14-line poem that often centers around love and relationships. Sonnets have different requirements depending on their form, but between lines 6-8, they all have a volta —a surprising line that twists and expands the poem’s meaning.

Let’s analyze three things related to the poem’s theme: its word choice, its use of simile and metaphor , and its volta.

Word Choice: Take a look at the words used to describe love. What do those words mean? What are their connotations? Here’s a brief list: “soul,” “ideal grace,” “quiet need,” “sun and candle-light,” “strive for right,” “passion,” “childhood’s faith,” “the breath, smiles, tears, of all my life,” “God,” “love thee better after death.”

These words and phrases all bear positive connotations, and many of them evoke images of warmth, safety, and the hearth. Even phrases that are morose, such as “lost saints” and “death,” are used as contrasts to further highlight the speaker’s wholehearted rejoicing of love. This word choice suggests an endless, benevolent, holistic, all-consuming love.

Simile and Metaphor: Similes and metaphors are comparison statements, and the poem routinely compares love to different objects and ideas. Here’s a list of those comparisons:

The speaker loves thee:

- To the depths of her soul.

- By sun and candle light—by day and night.

- As men strive to do the right thing (freely).

- As men turn from praise (purely).

- With the passion of both grief and faith.

- With the breath, smiles, and tears of her entire life.

- Now in life, and perhaps even more after death.

The speaker’s love seems to have infinite reach, flooding every aspect of her life. It consumes her soul, her everyday activities, her every emotion, her sense of justice and humility, and perhaps her afterlife, too. For the speaker, this love is not just an emotion, an activity, or an ideology: it’s her existence.

Volta: The volta of a sonnet occurs in the poem’s center. In this case, the volta is the lines “I love thee freely, as men strive for right. / I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.”

What surprising, unexpected comparisons! To the speaker, love is freedom and the search for a greater good; it is also as pure as humility. By comparing love to other concepts, the speaker reinforces the fact that love isn’t just an ideology, it’s an ideal that she strives for in every word, thought, and action.

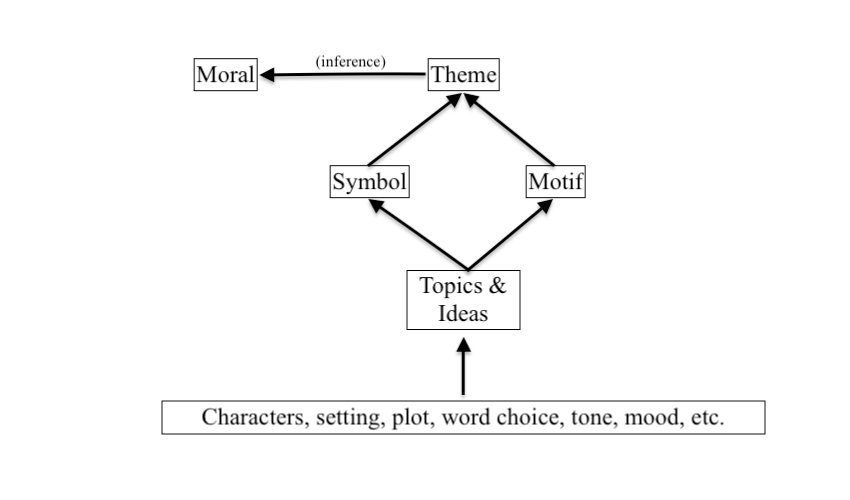

“Theme” is part of a broader hierarchy of ideas. While the theme of a story encompasses its central ideas, the writer also expresses these ideas through different devices.

You may have heard of some of these devices: motif, moral, topic, etc. What is motif vs theme? What is theme vs moral? These ideas interact with each other in different ways, which we’ve mapped out below.

Theme vs Topic

The “topic” of a piece of literature answers the question: What is this piece about? In other words, “topic” is what actually happens in the story or poem.

You’ll find a lot of overlap between topic and theme examples. Love, for instance, is both the topic and the theme of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “How Do I Love Thee.”

The difference between theme vs topic is: topic describes the surface level content matter of the piece, whereas theme encompasses the work’s apparent argument about the topic.

Topic describes the surface level content matter of the piece, whereas theme encompasses the work’s apparent argument about the topic.

So, the topic of Browning’s poem is love, while the theme is the speaker’s belief that her love is endless, pure, and all-consuming.

Additionally, the topic of a piece of literature is definitive, whereas the theme of a story or poem is interpretive. Every reader can agree on the topic, but many readers will have different interpretations of the theme. If the theme weren’t open-ended, it would simply be a topic.

Theme vs Motif

A motif is an idea that occurs throughout a literary work. Think of the motif as a facet of the theme: it explains, expands, and contributes to themes in literature. Motif develops a central idea without being the central idea itself .

Motif develops a central idea without being the central idea itself.

In Animal Farm , for example, we encounter motif when Napoleon the pig starts walking like a human. This represents the corrupting force of power, because Napoleon has become as much of a despot as Mr. Jones, the previous owner of the farm. Napoleon’s anthropomorphization is not the only example of power and corruption, but it is a compelling motif about the dangers of unchecked power.

Theme vs Moral

The moral of a story refers to the story’s message or takeaway. What can we learn from thinking about a specific piece of literature?

The moral is interpreted from the theme of a story or poem. Like theme, there is no single correct interpretation of a story’s moral: the reader is left to decide how to interpret the story’s meaning and message.

For example, in Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” the theme is loneliness, but the moral isn’t quite so clear—that’s for the reader to decide. My interpretation is that we should be much more sympathetic towards the lonely, since loneliness is a quiet affliction that many lonely people cannot express.

Great literature does not tell us what to think, it gives us stories to think about.

However, my interpretation could be miles away from yours, and that’s wonderful! Great literature does not tell us what to think, it gives us stories to think about, and the more we discuss our thoughts and interpretations, the more we learn from each other.

The theme of a story affects everything else: the decisions that characters make, the mood that words and images build, the moral that readers interpret, etc. Recognizing how writers utilize various themes in literature will help you craft stronger, more nuanced works of prose and poetry .

“To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme.” —Herman Melville

Whether a writer consciously or unconsciously decides the themes of their work, theme in literature acts as an organizing principle for the work as a whole. For writers, theme is especially useful to think about in the process of revision: if some element of your poem or story doesn’t point towards a central idea, it’s a sign that the work is not yet finished.

Moreover, literary themes give the work stakes . They make the work stand for something. Remember that our theme definition is an idea plus an opinion. Without that opinion element, a work of literature simply won’t stand for anything, because it is presenting ideas in the abstract without giving you something to react to. The theme of a story or poem is never just “love” or “justice,” it’s the author’s particular spin and insight on those themes. This is what makes a work of literature compelling or evocative. Without theme, literature has no center of gravity, and all the words and characters and plot points are just floating in the ether.

Should I Decide the Theme of a Story or Poem in Advance?

You can, though of course it depends on the actual story you want to tell. Some writers certainly start with a theme. You might decide you want to write a story about themes like love, family, justice, gender roles, the environment, or the pursuit of revenge.

From there, you can build everything else: plot points, characters, conflicts, etc. Examining themes in literature can help you generate some strong story ideas !

Nonetheless, theme is not the only way to approach a creative writing project. Some writers start with plot, others with character, others with conflicts, and still others with just a vague notion of what the story might be about. You might not even realize the themes in your work until after you finish writing it.

You certainly want your work to have a message, but deciding what that message is in advance might actually hinder your writing process. Many writers use their poems and stories as opportunities to explore tough questions, or to arrive at a deeper insight on a topic. In other words, you can start your work with ideas, and even opinions on those ideas, but don’t try to shoehorn a story or poem into your literary themes. Let the work explore those themes. If you can surprise yourself or learn something new from the writing process, your readers will certainly be moved as well.

So, experiment with ideas and try different ways of writing. You don’t have think about the theme of a story right away—but definitely give it some thought when you start revising your work!

Develop Great Themes at Writers.com

As writers, it’s hard to know how our work will be viewed and interpreted. Writing in a community can help. Whether you join our Facebook group or enroll in one of our upcoming courses , we have the tools and resources to sharpen your writing.

Sean Glatch

18 comments.

Sean Glatch,Thank you very much for your discussion on themes. It was enlightening and brought clarity to an abstract and sometimes difficult concept to explain and illustrate. The sample stories and poem were appreciated too as they are familiar to me. High School Language Arts Teacher

Hi Stephanie, I’m so glad this was helpful! Happy teaching 🙂

Wow!!! This is the best resource on the subject of themes that I have ever encountered and read on the internet. I just bookmarked it and plan to use it as a resource for my teaching. Thank you very much for publishing this valuable resource.

Hi Marisol,

Thank you for the kind words! I’m glad to hear this article will be a useful resource. Happy teaching!

Warmest, Sean

builders beams bristol

What is Theme? A Look at 20 Common Themes in Literature | writers.com

Hello! This is a very informative resource. Thank you for sharing.

farrow and ball pigeon

This presentation is excellent and of great educational value. I will employ it already in my thesis research studies.

John Never before communicated with you!

Brilliant! Thank you.

[…] THE MOST COMMON THEMES IN LITERATURE […]

marvellous. thumbs up

Thank you. Very useful information.

found everything in themes. thanks. so much

In college I avoided writing classes and even quit a class that would focus on ‘Huck Finn’ for the entire semester. My idea of hell. However, I’ve been reading and learning from the writers.com articles, and I want to especially thank Sean Glatch who writes in a way that is useful to aspiring writers like myself.

You are very welcome, Anne! I’m glad that these resources have been useful on your writing journey.

Thank you very much for this clear and very easy to understand teaching resources.

Hello there. I have a particular question.

Can you describe the exact difference of theme, issue and subject?

I get confused about these.

I love how helpful this is i will tell my class about it!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The 25 Most Common Themes in Literature and Why They Matter

by Sue Weems | 0 comments

If you've ever survived a high school English class, you've likely been asked to consider the most common themes in literature. What are they and why do they matter for readers and writers? Let's take a look.

Literature's first job is to entertain. But at the same time every novel has a kernel of truth in it, or perhaps several kernels, ideas about how life works or philosophies on the best way to live or some gesture to the broader meaning of life.

Taken together, these ideas may combine into a “theme.”

I say “may” because theme is more a tool of interpretation than creativity. The writer may come into the story with an idea of what their story is about. This understanding of what their story is “about ” may even help add focus and depth to their story.

Once a book is published, though, the audience owns theme, and they may depart with a totally different message than the author intended.

Which is all to say, as a writer, theme may or may not be helpful to you.

As a reader, though, you can use theme to unlock the deeper truths both in the story and in life. Let's look at what theme is, why it matters for readers and writers, how to identify them, and some common examples of theme in literature.

Why trust Sue on theme? I'm one of those annoying English teachers who helps students analyze literature. Students ask me why we do it, and I'll tell you the secrets I share with them: analyzing literature helps us understand our humanity and world– from the misuse of power to the meaning of life.

Secondly, learning to look at a part of something and understand how it functions in the whole (AKA analysis) is a skill that transcends literature. It's a low-stakes way to practice life skills.

Want to skip ahead? Click on the topic that best answers your question.

Table of Contents

What is a literary theme? Why does theme matter for a reader? How do you identify theme in a story? Types of story: a shortcut to theme Common themes in literature with examples Why theme matters for writers Practice

What is a literary theme?

A literary theme is a universal concept, idea or message explored in a story or poem. It's often a moral, lesson, or belief that the writer wants to convey to readers.

Think of theme as the underlying message that shapes the story. It’s not always obvious at first glance – sometimes it takes some close reading and analysis to identify what’s going on beneath the surface.

A universal theme is one that transcends time and place. For example, the popular theme “love conquers all” shows up in old romances such as The Epheseian Tale from 2-50 AD to Disney's Robin Hood from 1973 to Nicholas Sparks' novel The Notebook from 2004.

Why does theme matter for a reader?

You can certainly enjoy a story without knowing the theme explicitly, but most stories are about something beyond the character's actions. And we want them to be about something more.

Stories are the way we build meaning—the way we understand human life, the way we process and confront controversial ideas, the way we sometimes relate to each other on a universal level.

When someone asks you what a book you're reading is about, you likely give a sentence or two about the character, their goal, and the conflict, but you're just as likely to identify an abstract idea that the book is about. That idea is a touchpoint for our humanness.

I may not be into a book about a boy wizard who is swept into a world where he must overcome his fears and insignificance to defeat a formidable foe, but I can certainly understand what it means to belong, what it means to find your way through inadequacy, what it means to defeat your fears.

That's the power of theme. It points to deeper meaning, connecting me to a story and to other readers like me.

How do you identify theme in a story?

If you are a student or a writer trying to identify theme, it sometimes feels like trying to crack a secret English major code. But here's a trick I teach my students.

1. Find the big idea

First, ask yourself about the big ideas or concepts that seem important throughout the entire story. These may feel abstract, such as love, beauty, despair, justice, or art. Sometimes the main character has very defined beliefs (or misbeliefs!) about the idea.

2. Ask what the story suggests about the idea

Once you have one or two overarching central ideas that seem important for the story, then ask yourself this question: What does the story seem to say about this idea?

For example, if I'm reading Shirley Jackson's chilling short story “The Lottery,” I might identify that the story is about community and tradition. If I wanted to be a little more specific I'd say tradition in the vein of conformity.

Quick summary of the story (spoiler alert!): The story opens on a summer day when an entire community participates in their annual lottery. Each family in town draws a paper until a single community member has been selected. The end of the story shows the town stoning the “winner” in a barbarous act of solidarity to maintain community traditions.

Now, to identify the central theme, I'd ask myself, what does Jackson's story seem to say about community or tradition or conformity?

Some communities are willing to maintain their traditions (or conformity) at any cost.

3. Support the theme or message with examples

If I wanted to support the central theme I identified, I would pull quotes or examples from the story that support it. In this case, I could look at the children who are willing to participate, the contrast of the summer day and the dark deed, the insistence that the stoning will keep them prosperous, even though there is no evidence of such.

Are there other possible themes? Sure. There are no wrong answers, only themes that can be defended from the texts and those that don't have enough support. It takes a little practice, but try this technique and see if it doesn't help.

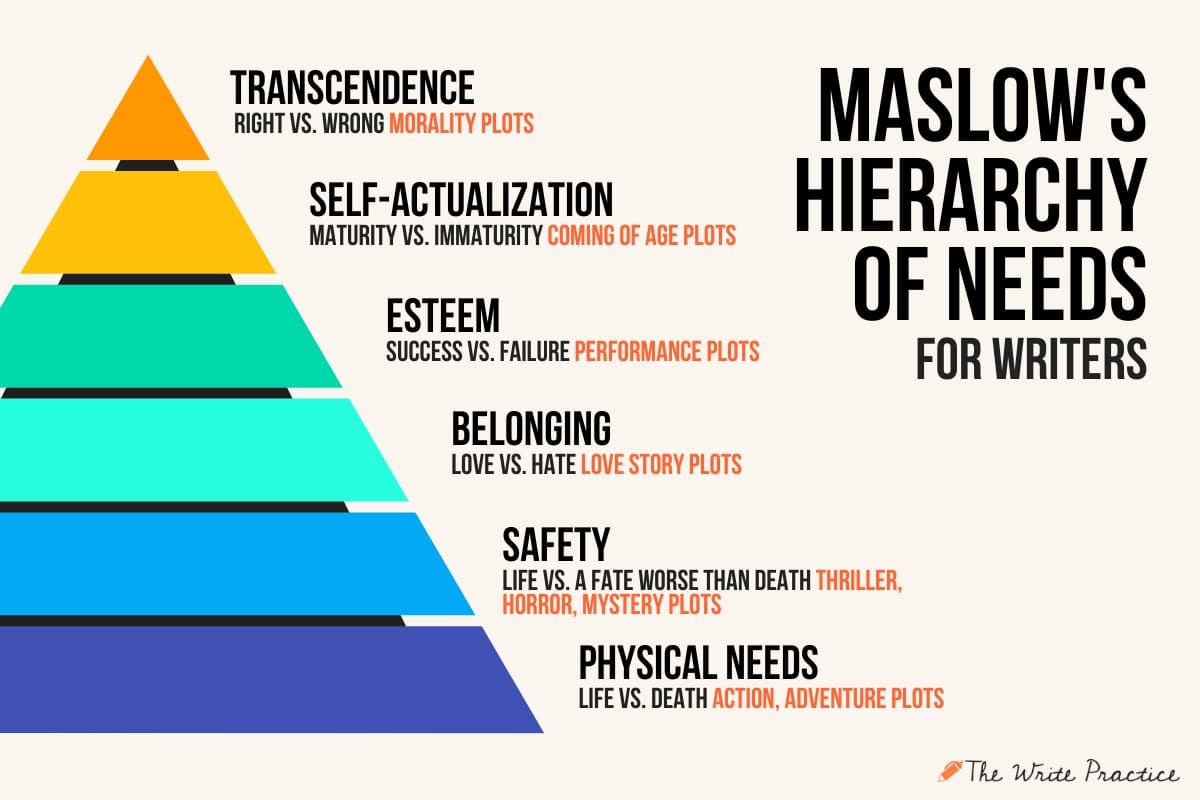

Types of Story: a shortcut to finding theme in a story

As a part of his book The Write Structure , Joe has identified several types of story that help writers plan and execute their books. The detailed post is here.

In short, Joe argues that all stories are built on six values frameworks, regardless of genre. The values are directly related to the human condition and identify base needs we have for moving through the world.

Knowing your story types and the value scale can be a short cut to identifying themes in books and stories, because those universal ideas are tucked inside the values.

Here are the values in each type of story:

- Survival from Nature > Life vs. Death

- Survival from Others > Life vs. Fate Worse than Death

- Love/Community > Love vs. Hate

- Esteem > Accomplishment vs. Failure

- Personal Growth > Maturity vs. Immaturity

- Transcendence > Right vs. Wrong

The types can help you identify the central ideas that the story speaks into because you know that the values will be key. Your question then is what does the story seem to say about this value? Or more specifically, what does the story seem to say about the way this particular character pursues this value?

For example: If you are reading a Jack London short story or novel, you know that the protagonist is going to be facing survival from nature. The value is life versus death. So to determine the theme we ask what does the story say about life vs death or survival?

In Jack London's short story “To Build a Fire,” an arrogant man trying to survive the Yukon wilderness makes a series of novice mistakes from traveling alone to getting wet with no way to get warm and dry. Spoiler alert, he dies.

What is the theme of this story? My students usually shout out something like, “Don't be a dummy and travel alone with no way to make a fire!” And they're not wrong. The ideas here are life, death, nature, and humanity. Here are a number of ways you could frame the theme with specific support from the story:

- Nature is indifferent to human suffering.

- Human arrogance leads to death.

- There are limits to self-reliance.

As you can see, the theme is what the story suggests about the story value.

Common themes in literature with examples

James Clear collected a list of the best-selling books of all time on his website . Let's start with some of those fiction titles.

Disclaimer: I know many of these summaries and themes are vastly oversimplified and most could be fleshed out in long, complicated papers and books. But for the sake of time, let's imagine my list as limited examples of theme among many that could be argued.

Disclaimer 2: I tried to get ChatGPT to help me write the one sentence summaries for these titles even though I've read all but two of the listed books. The summaries ChatGPT wrote were weak or too general for our purposes. So if there are errors below, they are all mine—I can't blame the bots today. Let's look at the list:

1. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605) summary: Aging nobleman Don Quixote deludes himself into thinking he's a knight and takes on a satirical quest to prove his honor by defending the helpless and defeating the wicked.

theme: Being born a nobleman (or any class) does not automatically determine your worth.

2. Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1859) summary: In this sprawling novel of swapped (or reconstructed) identities and class warfare during the French Revolution, characters navigate the nature of love, betrayal, justice, and the possibility of transformation.

theme: Transformation is possible for enlightened individuals and societies.

3. The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien (1954) summary: An unlikely hobbit and his diverse team set out to find and destroy a powerful ring to save Middle-earth and defeat the dark lord Sauron.

theme: Good can defeat evil when people (or creatures) are willing to sacrifice for the common good.

4. The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery (1943) summary: A prince visits various planets and discovers the importance of curiosity and openness to emotion.

theme: The most important things in life can't be seen with the eyes but with the heart.

5. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone by J.K. Rowling (1997) summary: An unsuspecting orphan attends a wizard school where he discovers his true identity, a dark foe, and the belonging he craves.

theme: Love and friendship transcend time and space.

6. And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie (1939) summary: Seven guests gather at a house on an island where they are killed off one-by-one as they try to discover the murderer.

theme: Death is inevitable, justice is not.

7. The Dream of the Red Chamber by Cat Xueqin (1791) summary: In this complex family drama, a nobleman's son is born with a magic jade in his mouth, and he rebels against social norms and his father resulting in an attempted arranged wedding and illness rather than reinforce oppression.

theme: Social hierarchies maintained by oppression will eventually fall.

8. The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien (1937) summary: Timid hobbit Bilbo Baggins is called by a wizard to help a band of dwarves reclaim their land from a terrible dragon, Smaug.

theme: Bravery can be found in the most unlikely places.

9. She: A History of Adventure by H. Rider Haggard (1886) summary: An professor and his ward seek out a lost kingdom in Africa to find a supernatural queen.

theme: Considering the imperialism of the time as well as worry about female empowerment, the themes here are varied and problematic, but perhaps one theme might resonate: Be careful what you seek, for you may find it.

10. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis (1950) summary: Four children venture through a wardrobe into a magical kingdom where they must work together to save Narnia, meet Aslan, and defeat the White Witch.

theme: Evil is overwhelmingly tempting and can only be defeated through sacrifice.

11. The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger (1951) summary: An expelled prep school student, Holden Caulfield, has a number of coming-of-age misadventures on his way home for the holiday break.

theme: Innocence can only be protected from the risks of growing up for so long.

12. The Alchemist by Paolo Coelho (1988) summary: A Spanish shepherd named Santiago travels to Egypt searching for treasure he saw in a dream.

theme: Anyone can make the world better if we are willing and courageous.

13. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1967) summary: This circle of life novel covers seven generations of the Buendia family as they build a small dysfunctional utopia in a swamp amidst a changing political and social Latin American landscape.

theme: Solitude is an inevitability for humankind.

14. Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery (1908) summary: An orphan finds her place with the Cuthbert siblings, and she brings her peculiar and delightful blend of imagination and optimism to their lives and community.

theme: Every human desires and deserves belonging.

15. Charlotte's Web by E.B. White (1952) summary: Wilbur the pig and his unconventional spider friend Charlotte join forces to save Wilbur's life from the slaughterhouse.

theme: Friendship can be found in the most unlikely places.

And let's throw in a few additional well-known stories and notable examples to see how their themes stack up:

16. Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare (1597) summary: Two teens from warring families fall in love and die rather than be kept apart from their families feud.

theme: Passion is costly.

17. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818) summary: An ambitious scientist creates a monster without considering the larger implications. Chaos ensues.

theme: Knowledge can be dangerous when coupled with unbridled ambition.

18. Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987) summary: Formerly enslaved mother Sethe and her daugher Denver are haunted by the ghost of Sethe's oldest daughter who died when she was two-years-old.

theme: The physical and psychological effects of slavery are damaging and long-lasting.

19. Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005) summary: In this dystopian novel, people are cloned and held in preparation to be life-long organ donors for others.

theme: Freedom is a basic human desire.

20. Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry (1959) summary: The Younger family grapples with identity and dreams in the wake of the death of their patriarch.

theme: Dignity and family are worth more than money.

The 5 most common themes in literature

You may have been asked to define universal themes as a part of a school assignment. Universal themes are those that transcend time and cultures, meaning they are often found to be true in real life no matter who you are or where you live.

Granted, I haven't read all the books across time and space (yet), but there's a pretty good bet that one of these major themes might apply to what you're reading regardless of time period, genre, or culture:

- Love conquers all.

- Things are not always what they seem.

- Good triumphs over evil.

- Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

- Blood (family) is thicker than water.

Which other larger themes would you list here as some of the most common in literature? Share your theme examples in the comments .

Why theme matters for writers

Why do themes matter for writers though? After all, isn't it enough to write an entertaining story? It can be, but exploring universal themes can help take your work to the next level. You don't have to identify a theme for your story and write everything to that end—in fact that might work against you. But when done well, it can enhance your story.

Here are a few reasons you may want to think about theme in your writing:

1. Coherence

Theme can bring together the various parts of a story, including plot and subplot, characters, symbols, and motifs. Readers can feel the variations on a theme laced throughout your story and done well, it's engaging and satisfying.

If your theme is love conquers all, then you likely have two people who over come incredible odds to be together. What are the other elements that subtly underscore it? Maybe there's a house that was built with love in the setting or maybe a secondary character is failing at love because they keep putting their work first. If it's subtle, those small details reinforce the main storyline.

2. Significance

As we discussed, universal themes will resonate with readers, even when they haven't experienced the same events. Many of the works we've listed above are remembered and revered due in part to their lasting themes about human experience.

3. Expression

Theme is an opportunity to weave together your world view, experiences, perspective, and beliefs with artistic and creative possibilities. Theme serves as a unifying element as you express your vision. Try playing with theme in a story or other creative work to see how it pushes boundaries or got beyond the expected.

In summary, theme can serve as the backbone of a story, giving it structure, depth, and resonance. It can help convey the writer's intended message and engage readers on multiple levels, making it a crucial element of literary and creative expression.

Which other larger themes would you list as the most common in literature? Share your theme examples in the comments .

Set your timer for 15 minutes . Choose one of the common themes above and create a character who has strong beliefs about that theme. Now, write a scene where an event or person challenges that belief. How will the character react? Will they double-down and insist on their worldview? Or will they soften and consider alternatives? Will shock at the challenge plunge them into despair? Play with their reaction.

Once you've written for 15 minutes, post your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop and leave feedback for a few other writers.

Sue Weems is a writer, teacher, and traveler with an advanced degree in (mostly fictional) revenge. When she’s not rationalizing her love for parentheses (and dramatic asides), she follows a sailor around the globe with their four children, two dogs, and an impossibly tall stack of books to read. You can read more of her writing tips on her website .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jun 30, 2021

What Is the Theme of a Story? Definition and Mistakes to Avoid

A theme is, broadly speaking, a story's central idea: a concept that underpins its narrative. Theme can either be a definitive message like, “greed is the greatest force in human culture,” or abstract ideas like love, loss, or betrayal.

As a writer, it’s helpful to stay conscious of your story’s themes to equip yourself with a compass to show you what’s important in your story. This will guide you toward creating moments that engage readers and deepen your story’s significance — so let’s take a look at why themes are important and how you can tell what a story’s theme is.

Themes make specific stories universal

All stories are about the human condition. Characters are bound by common universal truths of humanity.

Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman may not at first seem like an entirely relatable book. Its protagonist is someone who grounds her entire identity and purpose in being a convenience store worker — to the point where she wishes society accepted that as her ultimate aspiration and stopped pressuring her to date and get married.

I wished I was back in the convenience store where I was valued as a working member of staff and things weren’t as complicated as this.

While Murata's story is peculiar, the central conflict of her story (individual vs. society) is universal. It should resonate with most readers, making them more invested in the protagonist’s struggles, even if they don't share her specific experiences.

Authors can tackle complex ideas through narrative

Sometimes, the theme of a book will take the form of a hypothesis where the story plays out as a “what if” experiment. Here, authors have the chance to use characters as imagined case studies of human behavior, examining, for example, how different people react to the same events.

William Golding’s Lord of the Flies takes human morality as its central theme. It focuses on a group of boys stranded on an island and forced to fend for themselves. The children soon create their own micro-society on an island, with power structures, internal politics, and, eventually, violence. In short, the novel's thematic statement — its hypothesis — might be “If isolated from society, human beings would not act ‘morally’ anymore.”

By showing each character’s slightly different experience and perception of events, Golding explores how complex “morality” is — contrasting his characters' desire to conform with their sense of behaving correctly. In this way, the complexity of morality becomes the book’s organizing force, the central source of tension that propels the story forward.

A theme can organize and unite separate narrative strands

Not all books have a very tight focus on a single character or mission. Many novels and anthologies contain multiple, seemingly unrelated narratives or points of view united only by common themes.

James Joyce's Dubliners is made up of fifteen short stories, each set in the Irish capital in the early 20th century. His characters are all, in some way, touch by a sense of social paralysis or futility — something that readers have taken to be representative of Joyce's view on Ireland at the time. And as we meet more of these characters — the schoolboy obsessed with his friend's sister, the unfulfilled poet who's jealous of his old classmate, the bank teller who spurns the chaste affections of a married woman — this sense of stagnation and dread only grows.

Much like a music album will have a central concept that elevates it above being the sum of its parts, so too can themes connect disparate story strands in meaningful, insightful ways.

It can be hard to pin down what a story’s theme is, but if you're up to the task, here's a quiz to test your theme-detecting skills with! 🕵️

Test your theme-detecting skills!

See if you can identify five themes from five questions. Takes 30 seconds!

We hope we’ve shown you how indispensable story themes are. They’re much more than just a fun trick — stories simply are not the same without them.

In the next part of this series, we reveal some of the most common themes found in literature. When you're ready, let's continue our journey.

9 responses

Dennis Fleming says:

25/07/2017 – 16:08

Succinct and accurate. You put these ideas (theme, story, plot) into perspective for me. I wonder how you'd look at character (his or her motivations, reactions, dialogue) and how the idea of character is spread across these aspects of the novel.

PJ Reece says:

25/07/2017 – 17:29

Thanks -- theme is rarely spoken of. I'd only like to add a word of warning about starting a story with theme. The stories usually suck. They're preachy, awkward, self-conscious. Gives me the heebie-jeebies just thinking about it. But a good story will always contain a theme, even if it takes an independent reader to identify it. A good editor can guide the author into a rewrite based on the theme that has emerged in the story. That's why I love the rewrite phase -- meaning miraculous shows itself.

↪️ Reedsy replied:

25/07/2017 – 18:08

I'd largely agree with you. The human story feels like it should always take pride of place, as that's what the reader will latch on to — however, there are occasions where great books take a macro idea and then find stories illustrate the author's ideas. Thanks for reading!

ATinchini says:

29/07/2017 – 01:15

Usually I discover my theme during the outlining process. I start by describing the MC's life and his moment of conflict, what unleashes his journey and mission. When I describe the MC and one or two other characters, I get a hint of the theme, but I can only see it clearly while writing the early chapters of the first draft.

Rachael says:

30/07/2017 – 03:23

This is a wonderfully informative article, and it also helped me realize something about myself in regards to my writing and who I am as a person--a surprising and exhilarating thing to experience! Thinking back on my own writing, I recognized that the stories that mattered most to me were all exploring the same couple of emotions--and so is my current work in progress. Illuminating!

31/07/2017 – 10:57

Glad you found it helpful!

Al Pessin says:

01/08/2017 – 20:33

Many thanks for your interesting and useful article. I have one quibble. You name theme as (among others) “obsession and vengeance” and “role models and hero worship.” But it seems to me those are the subjects or issues addressed in the books, not the themes. For me, the theme is what the book says about those issues, and therefore pretty much has to have a verb, e.g. “obsession with vengeance destroys the vengeful” or “hero worship is dangerous.” That’s what the author is trying to say. The classic theme “man’s inhumanity to man” does not have a verb, but does imply a value judgement – inhumanity is assumed to be a bad thing. But even here, one can imagine a dystopian novel in which the theme could be “man’s inhumanity to man is necessary for the survival of humanity” in which the population is culled in a future of shortages or due to limited seating on space transport to a new planet when the Earth is about to be destroyed. It’s important for authors to know what they’re writing about, ideally before they start, and certainly before they finish. But I think they need to identify (for themselves) with a fair amount of specificity what it is they want to say about that subject, and write their story accordingly. Thanks again for the article.

Runesmith says:

07/09/2017 – 10:28

Several times I've had a theme emerge: my first novel was supposed to be just a post-apocalyptic adventure, but turned into an exploration of the practicality of pacifism. But if that happens you need to go back and integrate the theme you've discovered into the whole of the writing. And I completely disagree with your view of "Lord of the Flies". It's right there in the title: the boys are not corrupted by the emerging power structure, but by their wild natures, which Golding gives a voice in Simon's delirium before the pig's head. Jack's dominance is just a symptom.

Elizabeth says:

15/11/2019 – 08:27

Valuable information as always. Thank you.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Michael Bjork Writes

Story themes list: 100+ ideas to explore in your novel

Not sure what your story is about? Try this list of themes.

Themes are the universal ideas or topics your story explores.

And there are a lot of them. So many, in fact, the novel or story you’re working on probably already has a few, whether you realize it or not.

But that doesn’t mean your work is done.

Even though your story already has themes, you still need to identify and nurture them into something that resonates with your readers. Otherwise they’ll just sit there beneath the surface — stale, inert, unrealized.

That’s why I put together this story themes list, to help you:

- See and identify themes that might already be in your story, and

- Get a taste of just how many different kinds of themes are out there (because even this long list only scratches the surface).

How to use the list

Before you jump in, there’s something I want to point out.

The themes I included below are subjects and not messages . I explain the difference in my post that answered what is the theme of a story , but to quickly summarize, a subject is the broad topic you explore, while the message is what you’re trying to say about that subject. (Some call this the “thematic concept” and “thematic statement,” respectively.)

For example, “love” might be the subject of your story, but “love is difficult yet worthwhile” might be the message you want to share about the subject.

I didn’t provide messages, because I want you to feel empowered to use your own beliefs to fuel your handling of these themes.

That being said, your story doesn’t need a message if you don’t want it to. Stories can thrive on subjects alone. But as you look through this list and identify the themes that might be in your writing, you should also think about whether there’s anything you want to say about those topics.

All right, that’s all I have to say. Jump on in!

List of 100+ themes worth exploring

Experiences.

- Coming of Age

- Disillusionment

- Loss of Innocence

- Overcoming Adversity

- Self-discovery

Gender & Sexuality

- Gender Identity

- Masculinity

Human Perception

- Perception vs. Reality

- Subjectivity

Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Natural Forces

- Passage of Time

Politics & Economics

- Conservation

- Nationalism

Religion & Philosophy

- Determinism

- Good vs. Evil

- Metaphysics

- Nature vs. Nurture

- Soul / Consciousness

Social Issues

- Abuse of Power

- Immigration

- Progress & Regress

- Rights of the Oppressed

- Transphobia

- Working Class Struggles

Society & Culture

- Familial Obligations

- Individualism

- Responsibility

Technology & Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Augmented Reality

- Genetic Engineering

- Human Integration with Technology

- Information Privacy

- Weapons of Mass Destruction

Virtues & Vices

- Forgiveness

Want help identifying themes?

If you’re struggling with the concept of theme or how to identify and highlight them in your story, feel free to reach out in the comments below! I’m happy to help.

Follow this blog

Type your email…

Share this:

2 thoughts on “ story themes list: 100+ ideas to explore in your novel ”.

This is a nice list to get inspired! There are so many stories to write about all of these ideas!

Thanks! The crazy thing is this list still only scratches the surface of all the different themes out there. It’s both daunting and liberating to know!

Like Liked by 1 person

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Theme Definition

What is theme? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary themes is their universality, which is to say that themes are ideas that not only apply to the specific characters and events of a book or play, but also express broader truths about human experience that readers can apply to their own lives. For instance, John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (about a family of tenant farmers who are displaced from their land in Oklahoma) is a book whose themes might be said to include the inhumanity of capitalism, as well as the vitality and necessity of family and friendship.

Some additional key details about theme:

- All works of literature have themes. The same work can have multiple themes, and many different works explore the same or similar themes.

- Themes are sometimes divided into thematic concepts and thematic statements . A work's thematic concept is the broader topic it touches upon (love, forgiveness, pain, etc.) while its thematic statement is what the work says about that topic. For example, the thematic concept of a romance novel might be love, and, depending on what happens in the story, its thematic statement might be that "Love is blind," or that "You can't buy love . "

- Themes are almost never stated explicitly. Oftentimes you can identify a work's themes by looking for a repeating symbol , motif , or phrase that appears again and again throughout a story, since it often signals a recurring concept or idea.

Theme Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce theme: theem

Identifying Themes

Every work of literature—whether it's an essay, a novel, a poem, or something else—has at least one theme. Therefore, when analyzing a given work, it's always possible to discuss what the work is "about" on two separate levels: the more concrete level of the plot (i.e., what literally happens in the work), as well as the more abstract level of the theme (i.e., the concepts that the work deals with). Understanding the themes of a work is vital to understanding the work's significance—which is why, for example, every LitCharts Literature Guide uses a specific set of themes to help analyze the text.

Although some writers set out to explore certain themes in their work before they've even begun writing, many writers begin to write without a preconceived idea of the themes they want to explore—they simply allow the themes to emerge naturally through the writing process. But even when writers do set out to investigate a particular theme, they usually don't identify that theme explicitly in the work itself. Instead, each reader must come to their own conclusions about what themes are at play in a given work, and each reader will likely come away with a unique thematic interpretation or understanding of the work.

Symbol, Motif, and Leitwortstil

Writers often use three literary devices in particular—known as symbol , motif , and leitwortstil —to emphasize or hint at a work's underlying themes. Spotting these elements at work in a text can help you know where to look for its main themes.

- Near the beginning of Romeo and Juliet , Benvolio promises to make Romeo feel better about Rosaline's rejection of him by introducing him to more beautiful women, saying "Compare [Rosaline's] face with some that I shall show….and I will make thee think thy swan a crow." Here, the swan is a symbol for how Rosaline appears to the adoring Romeo, while the crow is a symbol for how she will soon appear to him, after he has seen other, more beautiful women.

- Symbols might occur once or twice in a book or play to represent an emotion, and in that case aren't necessarily related to a theme. However, if you start to see clusters of similar symbols appearing in a story, this may mean that the symbols are part of an overarching motif, in which case they very likely are related to a theme.

- For example, Shakespeare uses the motif of "dark vs. light" in Romeo and Juliet to emphasize one of the play's main themes: the contradictory nature of love. To develop this theme, Shakespeare describes the experience of love by pairing contradictory, opposite symbols next to each other throughout the play: not only crows and swans, but also night and day, moon and sun. These paired symbols all fall into the overall pattern of "dark vs. light," and that overall pattern is called a motif.

- A famous example is Kurt Vonnegut's repetition of the phrase "So it goes" throughout his novel Slaughterhouse Five , a novel which centers around the events of World War II. Vonnegut's narrator repeats the phrase each time he recounts a tragic story from the war, an effective demonstration of how the horrors of war have become normalized for the narrator. The constant repetition of the phrase emphasizes the novel's primary themes: the death and destruction of war, and the futility of trying to prevent or escape such destruction, and both of those things coupled with the author's skepticism that any of the destruction is necessary and that war-time tragedies "can't be helped."

Symbol, motif and leitwortstil are simply techniques that authors use to emphasize themes, and should not be confused with the actual thematic content at which they hint. That said, spotting these tools and patterns can give you valuable clues as to what might be the underlying themes of a work.

Thematic Concepts vs. Thematic Statements

A work's thematic concept is the broader topic it touches upon—for instance:

- Forgiveness

while its thematic statement is the particular argument the writer makes about that topic through his or her work, such as:

- Human judgement is imperfect.

- Love cannot be bought.

- Getting revenge on someone else will not fix your problems.

- Learning to forgive is part of becoming an adult.

Should You Use Thematic Concepts or Thematic Statements?

Some people argue that when describing a theme in a work that simply writing a thematic concept is insufficient, and that instead the theme must be described in a full sentence as a thematic statement. Other people argue that a thematic statement, being a single sentence, usually creates an artificially simplistic description of a theme in a work and is therefore can actually be more misleading than helpful. There isn't really a right answer in this debate.

In our LitCharts literature study guides , we usually identify themes in headings as thematic concepts, and then explain the theme more fully in a few paragraphs. We find thematic statements limiting in fully exploring or explaining a the theme, and so we don't use them. Please note that this doesn't mean we only rely on thematic concepts—we spend paragraphs explaining a theme after we first identify a thematic concept. If you are asked to describe a theme in a text, you probably should usually try to at least develop a thematic statement about the text if you're not given the time or space to describe it more fully. For example, a statement that a book is about "the senselessness of violence" is a lot stronger and more compelling than just saying that the book is about "violence."

Identifying Thematic Statements

One way to try to to identify or describe the thematic statement within a particular work is to think through the following aspects of the text:

- Plot: What are the main plot elements in the work, including the arc of the story, setting, and characters. What are the most important moments in the story? How does it end? How is the central conflict resolved?

- Protagonist: Who is the main character, and what happens to him or her? How does he or she develop as a person over the course of the story?

- Prominent symbols and motifs: Are there any motifs or symbols that are featured prominently in the work—for example, in the title, or recurring at important moments in the story—that might mirror some of the main themes?

After you've thought through these different parts of the text, consider what their answers might tell you about the thematic statement the text might be trying to make about any given thematic concept. The checklist above shouldn't be thought of as a precise formula for theme-finding, but rather as a set of guidelines, which will help you ask the right questions and arrive at an interesting thematic interpretation.

Theme Examples

The following examples not only illustrate how themes develop over the course of a work of literature, but they also demonstrate how paying careful attention to detail as you read will enable you to come to more compelling conclusions about those themes.

Themes in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby

Fitzgerald explores many themes in The Great Gatsby , among them the corruption of the American Dream .

- The story's narrator is Minnesota-born Nick Caraway, a New York bonds salesman. Nick befriends Jay Gatsby, the protagonist, who is a wealthy man who throws extravagant parties at his mansion.

- The central conflict of the novel is Gatsby's pursuit of Daisy, whom he met and fell in love with as a young man, but parted from during World War I.

- He makes a fortune illegally by bootlegging alcohol, to become the sort of wealthy man he believes Daisy is attracted to, then buys a house near her home, where she lives with her husband.

- While he does manage to re-enter Daisy's life, she ultimately abandons him and he dies as a result of her reckless, selfish behavior.

- Gatsby's house is on the water, and he stares longingly across the water at a green light that hangs at the edge of a dock at Daisy's house which sits across a the bay. The symbol of the light appears multiple times in the novel—during the early stages of Gatsby's longing for Daisy, during his pursuit of her, and after he dies without winning her love. It symbolizes both his longing for daisy and the distance between them (the distance of space and time) that he believes (incorrectly) that he can bridge.

- In addition to the green light, the color green appears regularly in the novel. This motif of green broadens and shapes the symbolism of the green light and also influences the novel's themes. While green always remains associated with Gatsby's yearning for Daisy and the past, and also his ambitious striving to regain Daisy, it also through the motif of repeated green becomes associated with money, hypocrisy, and destruction. Gatsby's yearning for Daisy, which is idealistic in some ways, also becomes clearly corrupt in others, which more generally impacts what the novel is saying about dreams more generally and the American Dream in particular.

Gatsby pursues the American Dream, driven by the idea that hard work can lead anyone from poverty to wealth, and he does so for a single reason: he's in love with Daisy. However, he pursues the dream dishonestly, making a fortune by illegal means, and ultimately fails to achieve his goal of winning Daisy's heart. Furthermore, when he actually gets close to winning Daisy's heart, she brings about his downfall. Through the story of Gatsby and Daisy, Fitzgerald expresses the point of view that the American Dream carries at its core an inherent corruption. You can read more about the theme of The American Dream in The Great Gatsby here .

Themes in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart

In Things Fall Apart , Chinua Achebe explores the theme of the dangers of rigidly following tradition .

- Okonkwo is obsessed with embodying the masculine ideals of traditional Igbo warrior culture.

- Okonkwo's dedication to his clan's traditions is so extreme that it even alienates members of his own family, one of whom joins the Christians.

- The central conflict: Okonkwo's community adapts to colonization in order to survive, becoming less warlike and allowing the minor injustices that the colonists inflict upon them to go unchallenged. Okonkwo, however, refuses to adapt.

- At the end of the novel, Okonkwo impulsively kills a Christian out of anger. Recognizing that his community does not support his crime, Okonkwo kills himself in despair.

- Clanswomen who give birth to twins abandon the babies in the forest to die, according to traditional beliefs that twins are evil.

- Okonkwo kills his beloved adopted son, a prisoner of war, according to the clan's traditions.

- Okonkwo sacrifices a goat in repentence, after severely beating his wife during the clan's holy week.

Through the tragic story of Okonkwo, Achebe is clearly dealing with the theme of tradition, but a close examination of the text reveals that he's also making a clear thematic statement that following traditions too rigidly leads people to the greatest sacrifice of all: that of personal agency . You can read more about this theme in Things Fall Apart here .

Themes in Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken

Poem's have themes just as plot-driven narratives do. One theme that Robert Frost explores in this famous poem, The Road Not Taken , is the illusory nature of free will .

- The poem's speaker stands at a fork in the road, in a "yellow wood."

- He (or she) looks down one path as far as possible, then takes the other, which seems less worn.

- The speaker then admits that the paths are about equally worn—there's really no way to tell the difference—and that a layer of leaves covers both of the paths, indicating that neither has been traveled recently.

- After taking the second path, the speaker finds comfort in the idea of taking the first path sometime in the future, but acknowledges that he or she is unlikely to ever return to that particular fork in the woods.

- The speaker imagines how, "with a sigh" she will tell someone in the future, "I took the road less travelled—and that has made all the difference."

- By wryly predicting his or her own need to romanticize, and retroactively justify, the chosen path, the speaker injects the poem with an unmistakeable hint of irony .

- The speaker's journey is a symbol for life, and the two paths symbolize different life paths, with the road "less-travelled" representing the path of an individualist or lone-wolf. The fork where the two roads diverge represents an important life choice. The road "not taken" represents the life path that the speaker would have pursued had he or she had made different choices.

Frost's speaker has reached a fork in the road, which—according to the symbolic language of the poem—means that he or she must make an important life decision. However, the speaker doesn't really know anything about the choice at hand: the paths appear to be the same from the speaker's vantage point, and there's no way he or she can know where the path will lead in the long term. By showing that the only truly informed choice the speaker makes is how he or she explains their decision after they have already made it , Frost suggests that although we pretend to make our own choices, our lives are actually governed by chance.

What's the Function of Theme in Literature?

Themes are a huge part of what readers ultimately take away from a work of literature when they're done reading it. They're the universal lessons and ideas that we draw from our experiences of works of art: in other words, they're part of the whole reason anyone would want to pick up a book in the first place!

It would be difficult to write any sort of narrative that did not include any kind of theme. The narrative itself would have to be almost completely incoherent in order to seem theme-less, and even then readers would discern a theme about incoherence and meaninglessness. So themes are in that sense an intrinsic part of nearly all writing. At the same time, the themes that a writer is interested in exploring will significantly impact nearly all aspects of how a writer chooses to write a text. Some writers might know the themes they want to explore from the beginning of their writing process, and proceed from there. Others might have only a glimmer of an idea, or have new ideas as they write, and so the themes they address might shift and change as they write. In either case, though, the writer's ideas about his or her themes will influence how they write.

One additional key detail about themes and how they work is that the process of identifying and interpreting them is often very personal and subjective. The subjective experience that readers bring to interpreting a work's themes is part of what makes literature so powerful: reading a book isn't simply a one-directional experience, in which the writer imparts their thoughts on life to the reader, already distilled into clear thematic statements. Rather, the process of reading and interpreting a work to discover its themes is an exchange in which readers parse the text to tease out the themes they find most relevant to their personal experience and interests.

Other Helpful Theme Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Theme: An in-depth explanation of theme that also breaks down the difference between thematic concepts and thematic statements.

- The Dictionary Definition of Theme: A basic definition and etymology of the term.

- In this instructional video , a teacher explains her process for helping students identify themes.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1899 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 39,983 quotes across 1899 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Protagonist

- Antimetabole

- Parallelism

- Blank Verse

- Slant Rhyme

- Figure of Speech

- Alliteration

- Dynamic Character

- Bildungsroman

- Polysyndeton

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

200 Common Themes in Literature

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is the theme of a story, common themes in literature, universal themes in literature, full list of themes in literature, theme examples in popular novels.

The theme of a novel is the main point of the story and what it’s really about. As a writer, it’s important to identify the theme of your story before you write it.

Themes are not unique to each novel because a theme addresses a common feeling or experience your readers can relate to. If you’re aware of what the common themes are, you’ll have a good idea of what your readers are expecting from your novel .

In this article, we’ll explain what a theme is, and we’ll explore common themes in literature.

The theme of a story is the underlying message or central idea the writer is trying to show through the actions of the main characters. A theme is usually something the reader can relate to, such as love, death, and power.

Your story can have more than one theme, as it might have core themes and minor themes that become more apparent later in the story. A romance novel can have the central theme of love, but the protagonist might have to overcome some self-esteem issues, which present the theme of identity.

Themes are great for adding conflict to your story because each theme presents different issues you could use to develop your characters. For example, a novel with the theme of survival will show the main character facing tough decisions about their own will to survive, potentially at the detriment of someone else they care about.

Sometimes a secondary character will represent the theme in the way they are characterized and the actions they take. Their role is to challenge the protagonist to learn what the story is trying to say about the theme. For example, in a novel about the fear of failure, the antagonist might be a rival in a competition who challenges the protagonist to overcome their fear so they can succeed against them.

It’s important to remember that a theme is not the same as a story’s moral message. A moral is a specific lesson you can teach your readers, whereas a story’s theme is an idea or concept your readers interpret in a way that relates to them.

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Common literary themes are concepts and central ideas that are relatable to most readers. Therefore, it’s a good idea to use a common theme if you want your novel to appeal to a wide range of readers.

Here’s our list of common themes in literature:

Love : the theme of love appears in novels within many genres, as it can discuss the love of people, pets, objects, and life. Love is a complex concept, so there are still unique takes on this theme being published every day.

Death/Grief : the theme of death can focus on the concept of mortality or how death affects people and how everyone processes grief in their own way.

Power : there are many books in the speculative fiction genres that focus on the theme of power. For example, a fantasy story could center on a ruling family and their internal problems and external pressures, which makes it difficult for them to stay in power.